Toxics or Lures? Biological and Behavioral Effects of Plant Essential Oils on Tephritidae Fruit Flies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

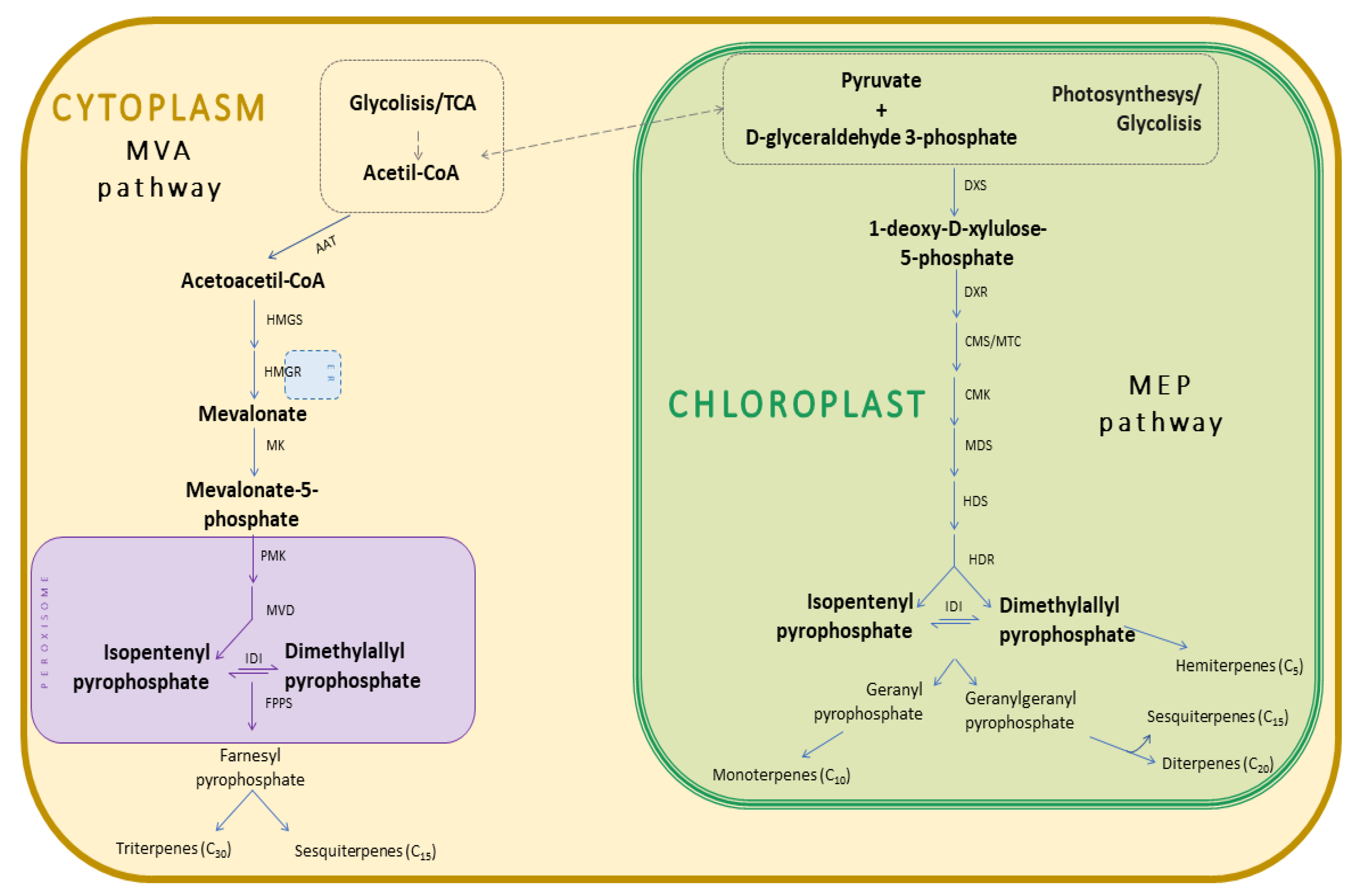

2. Biological Activity of Essential Oils and Their Constituents

2.1. Essential Oils as Lures

2.1.1. α-Copaene: A Booster of Mating Success in Ceratitis spp. and Anastrepha spp.

2.1.2. Methyl Eugenol: Rendezvous Cue or Sex Pheromone Precursor?

2.1.3. The Role of Cue Lure and Raspberry Ketone in Bactrocera and Zeugodacus Species

2.1.4. Other Compounds: α-Pinene and Zingerone

2.2. Essential Oils as Tephritid Repellents and Oviposition Deterrents

| Targeted Species | Tested EO/ Compound | Botanical Family/ Chemical Class | Observed Effect | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Cymbopogon winterianus | Poaceae | Oviposition deterrent | [111] | The oviposition deterrent effect was noted only on treated apples |

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Cymbopogon citratus | Poaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [127] | - |

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Cymbopogon giganteus | Poaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [127] | - |

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Cymbopogon nardus | Poaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [127] | - |

| Bactrocera cucurbitae | Cymbopogon schoenanthus | Poaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [127] | - |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Citrus limon | Rutaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Corymbia citriodora | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Eucalyptus staigeriana | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Eucalyptus radiata | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Eucalyptus dives | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Leptospermum petersonii | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Mentha × piperita | Lamiaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Bactrocera tryoni | Melaleuca teretifolia | Myrtaceae | Oviposition deterrent Repellent | [112] | Additionally, vegetable oils of Carthamus tinctorius, Gossypium herbaceum, Linum usitatissimum, and Azadirachta indica were tested |

| Ceratitis capitata | Citrus limon cv. “Lunario” | Rutaceae | Repellent | [114] | Field bioassays |

| Ceratitis capitata | Citrus limon cv. “Interdonato” | Rutaceae | Repellent | [114] | Field bioassays |

| Ceratitis capitata | Tagetes minuta | Asteraceae | Repellent | [113] | The repellent effect was observed towards females of C. capitata. Differently, males were attracted by this EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Linalool | Terpene | Oviposition deterrent | [115] | One of the major compounds of citrus peel EOs. Females are repelled by this compound while males gain a mating advantage |

2.3. Essential Oils as Toxins

2.3.1. Fumigant Toxicity of Essential Oils and Their Main Compounds

| Species | Stage | Tested EO | Botanical Family | Main Constituents | Mortality Rates | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%); α-pinene (5.36%) | ♂ 6.30 ± 0.27 days ♀ 6.76 ± 0.28 days | [46] | Mortality is expressed as the longevity of males and females after exposure to the EO |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | ♂ 9.02 ± 0.23 days ♀ 8.88 ± 0.24 days | [46] | Mortality is expressed as the longevity of males and females after exposure to the EO |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Cymbopogon citratus | Poaceae | Purchased EO | 62.5% on peach | [111] | EO dose 1% (w/v) |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Cymbopogon winterianus | Poaceae | Purchased EO | 80% on apple 100% on peach | [111] | EO dose 10% (w/v) |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Ruta graveolens | Rutaceae | Purchased EO | Low mortality | [111] | EO dose 0.05% (w/v) |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Purchased EO | LC50: 0.1–1% | [45] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Cymbopogon nardus | Poaceae | Purchased EO | Low mortality | [130] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Myrtaceae | Purchased EO | 100% (after 12 h) | [130] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Eugenia caryophyllata | Myrtaceae | Purchased EO | 87.5% (after 72 h) | [130] | On day 15 |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Purchased EO | 95% (after 72 h) | [130] | On day 15 |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Mentha × piperita | Lamiaceae | Linalool (40.4%); linalyl acetate (32.6%); α-terpineol (6.4%) | LC50: 0.27 μL/L air LC90: 0.45 μL/L air | [132] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Mentha pulegium | Lamiaceae | Pulegone (77.3%); menthone (10.8%) | [132] | ||

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Mentha rotundifolia | Lamiaceae | Menthone (28.5%); iso-menthone (19%); neo-menthol (10.4%) | [132] | ||

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Mentha spicata | Lamiaceae | Carvone (54.1%); limonene (21.9%) | LC50: 0.22 μL/L air LC90: 0.33 μL/L air | [132] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Ammoides verticillata | Apiaceae | Carvacrol (44.3%); limonene (19.3%); p-cymene (19.2%); γ-terpinene (11.1%) | LC50: <2 μL/L air | [142] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Pupae | Ammoides verticillata | Apiaceae | Carvacrol (44.3%); limonene (19.3%); p-cymene (19.2%); γ-terpinene (11.1%) | LC50: 7.2 μL/L air air | [142] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Ammoides verticillata | Apiaceae | Carvacrol (44.3%); limonene (19.3%); p-cymene (19.2%); γ-terpinene (11.1%) | LC50: 10.1 μL/L air air | [142] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Hyptis suaveolens | Lamiaceae | Sabinene (34.0%); β-caryophyllene (11.2%); terpinolene (10.7%); β-pinene (8.2%) | LC50: 18.33 μL/L air air | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | Linalool (36.5%); linalyl acetate (14.4%); camphor (8.5%); 1,8-cineole (7.9%) | LC50: 9.08 μL/L air air | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (34.3%); α-pinene (11.9%); borneol (10.0%) | LC50: 16.72 μL/L air | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thuja occidentalis | Cupressaceae | δ-3-carene (33.2%); α-pinene (27.7%); cedrol (10.3%); terpinolene (5.7%) | LC50: 33.90 μL/L air air | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Melaleuca alternifolia | Myrtaceae | Terpinen-4-ol (35.1%); γ-terpinene (17.4%); α-terpinene (10.7%); 1,8-cineole (5.5%) | LC50: 2.24 μL/L air air | [48] | LC50 on Psyttalia concolor: 9.35 μL/L air |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%); α-pinene (5.36%) | ♂ 7.23 ± 0.24 days ♀ 9.61 ± 0.22 days | [46] | Mortality is expressed as the longevity of males and females after the exposition to the EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | ♂ 4.92 ± 0.24 days ♀ 6.64 ± 0.29 days | [46] | Mortality is expressed as the longevity of males and females after the exposition to the EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Purchased EO | LC50: 1–2.5% | [45] | |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Cymbopogon nardus | Poaceae | Purchased EO | Low mortality | [130] | |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Purchased EO | LC50: 1–2.5% | [45] | sub Bactrocera |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Myrtaceae | Purchased EO | 100% (after 12 h) | [130] | |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Eugenia caryophyllata | Myrtaceae | Purchased EO | 76.7% (after 72 h) | [130] | On day 15 |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Purchased EO | 40.0% (after 72 h) | [130] | On day 15 |

| Species | Stage | Tested Substance | Chemical Class | Mortality Rates | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Egg | Citral | Monoterpenoid | LC50: 0.04 μL/cm3 air LC90: 0.16 μL/cm3 air | [141] | |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Egg | Limonene | Monoterpene | LC50: 0.16 μL/cm3 air LC90: 0.27 μL/cm3 air | [141] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Estragole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 1–2.5% | [45] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | LC50: 1–2.5% | [45] | |

| Bactrocera dorsalis | Adult | trans-Anethole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.1–1% | [45] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Estragole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.75–1% | [45] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | LC50: 1–2.5% | [45] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Methyl eugenol | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.25–0.5% | [45] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | trans-Anethole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.75–1% | [45] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | trans-Anethole | Phenylpropanoid | logLC50: 0.2–0.3 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | α-Pinene | Monoterpene | logLC50: 1.2–1.5 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Carvacrol | Monoterpenoid | logLC50: ~0.5 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Cinnamaldehyde | Phenylpropanoid | logLC50: ~0.4 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Cuminaldehyde | Phenylpropanoid | logLC50: 0.2–0.3 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Eugenol | Phenylpropanoid | logLC50: ~1 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | logLC50: 0.5–0.7 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | p-Cymene | Phenylpropanoid | logLC50: 1.5–1.8 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Terpineol | Monoterpenoid | logLC50: ~0.5 | [134] | Compound tested in M·cm−3, LC50 unit not provided in Figure 1 |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Estragole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 1% | [45] | sub Bactrocera |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | LC50: 2.5–5% | [45] | sub Bactrocera |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | trans-Anethole | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.75–1% | [45] | sub Bactrocera |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Methyl eugenol | Phenylpropanoid | LC50: 0.25–0.5% | [45] | sub Bactrocera |

2.3.2. Topical/Contact Toxicity of Essential Oils and Their Main Compounds

| Species | Stage | Tested EO | Botanical Family | Main Constituents | Mortality Rates | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Pupa | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%) | Adult emergence 21% | [33] | |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Pupa | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | Adult emergence 15% | [33] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Mentha pulegium | Lamiaceae | Pulegone (75.7%); menthone (10.1%) | LD50: 1.79 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Salvia fruticosa | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (52.5%); α-thujone (8.3%); β-thujone (3.1%); camphor (0.9%) | LD50: 0.22 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Baccharis spartoides | Asteraceae | α-phellandrene (44.5%); sabinene (20.7%); β-pinene (15.9%) | LD50: 14.60 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 10.7 μg/fly ♀ | [160] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Schynus polygama | Anacardiaceae | δ-cadinene (7.8%); γ-cadinene (5.3%); β-caryophyllene (5.1%); trans-muurola-4(14),5-diene (4.7%); terpinene (4.6%); α-pinene (4.2%) | LD50: 10.3 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 22.0 μg/fly ♀ | [160] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Hyptis suaveolens | Lamiaceae | Sabinene (34.0%); β-caryophyllene (11.2%); terpinolene (10.7%); β-pinene (8.2%) | LD50: 0.066 μL/fly | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | Linalool (36.5%); linalyl acetate (14.4%); camphor (8.5%); 1,8-cineole (7.9%) | LD50: 0.017 μL/fly | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (34.3%); α-pinene (11.9%); borneol (10.0%) | LD50: 0.047 μL/fly | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thuja occidentalis | Cupressaceae | δ-3-carene (33.2%); α-pinene (27.7%); cedrol (10.3%); terpinolene (5.7%) | LD50: 0.024 μL/fly | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Melaleuca alternifolia | Myrtaceae | Terpinen-4-ol (35.1%); γ-terpinene (17.4%); α-terpinene (10.7%); 1,8-cineole (5.5%) | LD50: 0.117 μL/cm2 | [48] | LD50 on Psyttalia concolor: 0.147 μL/cm2 |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Baccharis darwinii | Asteraceae | Limonene (47.1%); thymol (8.1%); sabinene (5.7%); myrcene (3.6%); α-pinene (4.6%); α-terpineol (3.7%) | LD50: 19.9 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 30 μg/fly ♀ | [161] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Tagetes minuta | Asteraceae | cis-tagetone (62.4%); trans-β-ocimene (16.2%); dihydrotagetone (10.3%) | LD50: 18.32 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 14.74 μg/fly ♀ | [113] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Tagetes rupestris | Asteraceae | trans-ocimenone (39.3%); trans-tagetone (24.4%); cis-β-ocimene (6.1%); cis-ocimenone (5.9%) | LD50: 14.50 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 5.69 μg/fly ♀ | [113] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Tagetes ternifolia | Asteraceae | cis-tagetone (31.0%); cis-β-ocimene (15.4%); trans-ocimenone (15.4%); cis-ocimenone (14.5%); trans-tagetone (10.3%); dihydrotagetone (6.5%) | LD50: 19.97 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 16.17 μg fly ♀ | [113] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Azorella cryptantha | Apiaceae | α-pinene (21.9%); α-thujene (12.5%); cadinene (8.6%); sabinene (6.4%); δ-trans-β-guaiene (6.2%) | LD50: 2.60 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 9.54 μg/fly ♀ | [162] | The plant species has been collected in Bauchaceta (Argentina) |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Azorella cryptantha | Apiaceae | α-thujene (5.7%); α-pinene (9.6%); β-pinene (5.9%); γ-cadinene (4.0%); δ-cadinene (6.3%) | LD50: 10.78 μg/fly ♂ LD50: 8.39 μg/fly ♀ | [162] | The plant species has been collected in Aqua Negra (Argentina) |

| Ceratitis capitata | Pupa | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%); α-pinene (5.36%) | Adult emergence 0% | [33] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Pupa | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | Adult emergence 0% | [33] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Amyris balsamifera | Rutaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.014 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.026 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Cedrus atlantica | Pinaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.012 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.015 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Corymbia citriodora | Myrtaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.032 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.033 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Cymbopogon citratus | Poaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.014 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.022 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Pelargonium Graveolens | Geraniaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.029 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.029 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | CEL (C. atlantica + C. citriodora + C. citratus) | Pinaceae + Myrtaceae + Poaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.018 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.018 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | Additive effect |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | SLD (A. balsamifera + C. citratus + C. atlantica) | Rutaceae + Poaceae + Pinaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.016 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.018 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | Additive effect |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | GES (P. graveolens + C. citriodora + A. balsamifera) | Geraniaceae + Myrtaceae + Rutaceae | Purchased EO | LD50: 0.015 μL/fly ♂ LD50: 0.029 μL/fly ♀ | [131] | Additive effect |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Peperomia borbonensis | Piperaceae | Decanal (7.3%); δ-elemene (4.9%); myristicin (39.5%); elemicin (26.6%) | LD50: 0.23 μg/cm2 LD90: 0.34 μg/cm2 | [170] | sub Bactrocera |

| Species | Stage | Tested Substance | Chemical Class | Mortality Rates | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Egg | Citral | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 12.82 μL/mL LD90: 16.79 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Larva | Citral | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 1.62 μL/mL LD90: 4.98 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Egg | Limonene | Monoterpene | LD50: 34.04 μL/mL LD90: 80.37 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Larva | Limonene | Monoterpene | LD50: 0.84 μL/mL LD90: 23.93 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | 1,8-Cineole | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 0.50 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Camphor | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 1.45 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Menthone | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 0.13 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Pulegone | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 0.09 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Larva | Thujone | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 0.82 μL/mL | [169] | |

| Bactrocera zonata | Larva | (1R, 2S, 5R)- Menthol | Monoterpenoid | LD50: <20 mg/kg | [148] | After 72 h |

| Bactrocera zonata | Larva | (R)-Camphor | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 23.68 mg/kg | [148] | After 72 h |

| Bactrocera zonata | Larva | (R)-carvone | Monoterpenoid | LD50: <20 mg/kg | [148] | After 72 h |

| Ceratitis capitata | Egg | Citral | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 22.44 μL/mL LD90: 41.76 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Citral | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 3.18 μL/mL LD90: 7.69 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Egg | Limonene | Monoterpene | LD50: 77.06 μL/mL LD90: 119.64 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Limonene | Monoterpene | LD50: 2.30 μL/mL LD90: 2.28 μL/mL | [141] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Limonene | Monoterpene | LD50: 8.34 nL/fly ♂ LD90: 44.01 nL/fly ♂ LD50: 31.72 nL/fly ♀ LD90: 155.77 nL/fly ♀ | [124] | Diet yeast + sugar |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | LD50: 10.37 nL/fly ♂ LD90: 57.05 nL/fly ♂ LD50: 49.39 nL/fly ♀ LD90: 210.42 nL/fly ♀ | [124] | Diet yeast + sugar |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | α-Pinene | Monoterpene | LD50: 7.71 nL/fly ♂ LD90: 30.34 nL/fly ♂ LD50: 17.20 nL/fly ♀ LD90: 71.32 nL/fly ♀ | [124] | Diet yeast + sugar |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Elemicin | Phenylpropanoid | <40% | [170] | Tested separately according to the ratio found in the EO. Reported sub Bactrocera |

| Zeugodacus cucurbitae | Adult | Myristicin | Phenylpropanoid | <40% | [170] | Tested separately according to the ratio found in the EO. Reported sub Bactrocera |

2.3.3. Ingestion Toxicity of Essential Oils and Their Main Compounds

| Species | Stage | Tested EO | Botanical Family | Main Constituents | Mortality Rates | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%) | Living adults 58.67% | [33] | Results about A. fraterculus were combined with the C. capitata ones |

| Anastrepha fraterculus | Adult | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | Living adults 70.33% | [33] | Results about A. fraterculus were combined with the C. capitata ones |

| Anastrepha ludens | Adult | Eugenia caryophyllata | Myrtaceae | Eugenol (77.58%); acetyl eugenol (10.99%); β-caryophyllene (6.22) | LD50: 3529 ppm LD90: 7763 ppm | [174] | |

| Anastrepha ludens | Adult | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Estragole (72.64%); linalool (16.65%) | LD50: 8050 ppm LD90: 25,846 ppm | [174] | |

| Anastrepha ludens | Adult | Thymus vulgaris | Lamiaceae | p-cymene (32.49%); α-terpineol (12.58%); linalool (5.29%) | LD50: 5347 ppm LD90: 18,113 ppm | [174] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Hyptis suaveolens | Lamiaceae | Sabinene (19.5%); β-caryophyllene (16.2%); terpinen-4-ol (7.7%); terpinolene (7.4%); β-pinene (6.7%) | LD50: 4922 ppm | [5] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | Linalool (39.5%); linalyl acetate (18.2%); camphor (9.7%); 1,8-cineole (6.5%); borneol (6.6%) | LD50: 6271 ppm | [5] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (18.6%); α-pinene (15.6%); camphor (15.3%); borneol (9.2%); verbenone (8.2%) | LD50: 5107 ppm | [5] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Ocimum gratissimum | Lamiaceae | Thymol (57.0%); p-cymene (12.4%); γ-terpinene (6.9%) | LD50: 925 ppm LD90: 6365 ppm | [47] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Pimpinella anisum | Apiaceae | trans-anethole (98.3%) | LD50: 771 ppm LD90: 1981 ppm | [47] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Thymbra spicata | Lamiaceae | Carvacrol (41.4%); p-cymene (41.2%); γ-terpinene (5.5%); thymol (5.2%) | LD50: 2509 ppm LD90: 12,519 ppm | [47] | |

| Bactrocera oleae | Adult | Trachyspermum ammi | Apiaceae | Thymol (58.3%); p-cymene (24.7%); γ-terpinene (14.2%) | LD50: 633 ppm LD90: 2131 ppm | [47] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Hyptis suaveolens | Lamiaceae | Sabinene (34.0%); β-caryophyllene (11.2%); terpinolene (10.7%); β-pinene (8.2%) | LD50: 13,041 ppm | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | Linalool (36.5%); linalyl acetate (14.4%); camphor (8.5%); 1,8-cineole (7.9%) | LD50: 6860 ppm | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (34.3%); α-pinene (11.9%); borneol (10.0%) | LD50: 3664 ppm | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thuja occidentalis | Cupressaceae | δ-3-carene (33.2%); α-pinene (27.7%); cedrol (10.3%); terpinolene (5.7%) | LD50: 5371 ppm | [49] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Melaleuca alternifolia | Myrtaceae | Terpinen-4-ol (35.1%); γ-terpinene (17.4%); α-terpinene (10.7%); 1,8-cineole (5.5%) | LD50: 0.269% (w/v) | [48] | LD50 on Psyttalia concolor: 0.639% w/w |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Carlina acaulis | Asteraceae | Carlina oxide (97.7%) | LD50: 1094 ppm LD90: 3082 ppm | [171] | Sublethal effect on aggressive behavior |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Trachyspermum ammi | Apiaceae | Thymol (64.7%); p-cymene (17.0%); γ-terpinene (14.8%) | LD50: 3969 ppm LD90: 8200 ppm | [171] | Sublethal effect on aggressive behavior |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Teucrium leucocladum | Lamiaceae | Patchouli alcohol (31.24%); β-pinene (12.66%); α-pinene (10.99%); cedrol (10.3%) | LD50: 24 ppm | [181] | |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Mentha pulegium | Lamiaceae | Pulegone (27.3%); menthol (22.0%); menthone (14.0%); iso-menthone (14.0%) | >95% of adults | [172] | After 48 h, the emulsion contained 0.25% (w/v) of EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thymbra capitata | Lamiaceae | 1,8-cineole (68.0%) | <35% of adults | [172] | After 48 h, the emulsion contained 0.25% (w/v) of EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thymus albicans | Lamiaceae | Carvacrol 82% | 15–20% of adults | [172] | After 48 h, the emulsion contained 0.25% (w/v) of EO |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Baccharis dracunculifolia | Asteraceae | β-pinene (22.69%); limonene (19.07%); nerolidol (8.08%); γ-elemene (7.80%); β-caryophyllene (6.17%) | Living adults 58.67% | [33] | Results about C. capitata were combined with the A. fraterculus ones |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Pinus elliottii | Pinaceae | α-pinene (39.25%); β-pinene (34.79%); β-phellandrene (11.93%); limonene (9.31%) | Living adults 70.33% | [33] | Results about C. capitata were combined with the A. fraterculus ones |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Citrus aurantium | Rutaceae | Limonene (96.7%) | >99% of adults | [126] | Dose 13 mL/g |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Citrus limon | Rutaceae | Limonene (74.3%); γ-terpinene (6.4%); β-pinene (7.0%) | >99% of adults | [126] | Dose 16.5 mL/g |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Citrus sinensis | Rutaceae | Limonene (97.4%) | >99% of adults | [126] | Dose 13 mL/g |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | α-pinene (33.95); 1,8-cineole (11.24%); bornyl acetate (7.80%); camphene (7.51%); farnesol (6.02%) | Low activity | [173] | After 72 h |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Salvia officinalis | Lamiaceae | Camphor (26.85%); α-thujone (23.00%); 1,8-cineole (11.82%); camphene (5.80%) | Low activity | [173] | After 72 h |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thymus capitatus | Lamiaceae | Carvacrol (68.91%); γ-terpinene (6.33%); p-cymene (6.17%); β-caryophyllene (5.20%) | LD50: 93.0% (w/w) | [173] | After 72 h |

| Ceratitis capitata | Adult | Thymus herba barona | Lamiaceae | Carvacrol (44.59%); p-cymene (5.97%); γ-terpinene (5.56%); borneol (5.39%) | LD50: 91% (w/w) | [173] | After 72 h |

| Species | Stage | Tested Substance | Chemical Class | Mortality Rates | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | α-Terpineol | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | (+)-β-Pinene | Monoterpene | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Citral | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Geranyl acetate | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | γ-Terpinene | Monoterpene | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Linalool | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Linalyl acetate | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Myrcene | Monoterpene | 9.6 μL/g food | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Neryl acetate | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | R-(+)-limonene | Monoterpene | 6.2 μL/g food | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | S-(−)-limonene | Monoterpene | 7 μL/g food | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | Terpinen-4-ol | Monoterpenoid | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | (−)-trans-Caryophyllene | Sesquiterpene | 8.3 μL/g food | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | (+)-Valencene | Sesquiterpene | 10.4 μL/g food | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | (−)-α-Pinene | Monoterpene | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

| Ceratitis capitata | Larva | (+)-α-Pinene | Monoterpene | The LD50 value is reported only graphically | [126] |

3. Mechanisms of Action of Essential Oils

4. Tephritid and Essential Oils: Real-World Applications and Challenges

5. Conclusions, Future Perspectives, and Challenges

- Multiple mechanisms of action, therefore the development of resistance is unlikely.

- Low toxicity towards non-target organisms (including humans).

- Low health risk throughout the application due to their limited toxicity.

- High effectiveness towards a wide range of pests of agricultural, veterinary, and medical interest.

- Strict legislation.

- Uneven EO chemical composition depending on cultivation, harvesting and extraction conditions.

- Phytotoxic properties to crops and other non-target plant species.

- EO physio-chemical properties, such as thermolability and washability, reduce their stability and efficacy in field conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, I.M.; Elson-Harris, M.M. Fruit Flies of Economic Significance: Their Identification and Bionomics; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ekesi, S.; Mohamed, S.A. Mass Rearing and Quality Control Parameters for Tephritid Fruit Flies of Economic Importance in Africa. In Wide Spectra of Quality Control; Akyar, I., Ed.; InTechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X. An intelligent identification system combining image and DNA sequence methods for fruit flies with economic importance (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Johnson, M.W. Olive Fruit Fly: Managing an Ancient Pest in Modern Times. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, A.; Benelli, G.; Conti, B.; Lenzi, G.; Flamini, G.; Francini, A.; Cioni, P.L. Ingestion toxicity of three Lamiaceae essential oils incorporated in protein baits against the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera Tephritidae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.I.; Shelly, T.E.; Leblanc, L.; Piñero, J.C. Recent Advances in Methyl Eugenol and Cue-Lure Technologies for Fruit Fly Detection, Monitoring, and Control in Hawaii; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 575–595. [Google Scholar]

- Lauzon, C.R.; Potter, S.E. Description of the irradiated and nonirradiated midgut of Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Anastrepha ludens Loew (Diptera: Tephritidae) used for sterile insect technique. J. Pest Sci. 2012, 85, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Daane, K.M.; Canale, A.; Niu, C.Y.; Messing, R.H.; Vargas, R.I. Sexual communication and related behaviours in Tephritidae: Current knowledge and potential applications for Integrated Pest Management. J. Pest Sci. 2014, 87, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.I.; Leblanc, L.; Harris, E.J.; Manoukis, N.C. Regional Suppression of Bactrocera Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Pacific through Biological Control and Prospects for Future Introductions into Other Areas of the World. Insects 2012, 3, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sivinski, J.; Aluja, M. The Roles of Parasitoid Foraging for Hosts, Food and Mates in the Augmentative Control of Tephritidae. Insects 2012, 3, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benelli, G.; Revadi, S.; Carpita, A.; Giunti, G.; Raspi, A.; Anfora, G.; Canale, A. Behavioral and electrophysiological responses of the parasitic wasp Psyttalia concolor (Szépligeti) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) to Ceratitis capitata induced fruit volatiles. Biol. Control 2013, 64, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, H.; Claudianos, C.; Ortelli, F.; Abgrall, C.; Hemingway, J.; Sharakhova, M.V.; Unger, M.F.; Collins, F.H.; Feyereisen, R. Evolution of supergene families associated with insecticide resistance. Science 2002, 298, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantz, A.; Camon, J.; Froger, J.A.; Goven, D.; Raymond, V. Exposure to sublethal doses of insecticide and their effects on insects at cellular and physiological levels. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 30, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.Y.; Cha, B.; Kim, J.C. Recent trends in studies on botanical fungicides in agriculture. Plant Pathol. J. 2013, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebadollahi, A.; Jalali Sendi, J. A review on recent research results on bio-effects of plant essential oils against major Coleopteran insect pests. Toxin Rev. 2015, 34, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Grieneisen, M.L. Botanical insecticide research: Many publications, limited useful data. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R. Beyond mosquitoes—Essential oil toxicity and repellency against bloodsucking insects. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 117, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Machial, C.M. Pesticides based on plant essential oils: From traditional practice to commercialization. In Advances in Phytomedicine; Rai, M., Carpinella, M.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierascu, R.C.; Fierascu, I.C.; Dinu-Pirvu, C.E.; Fierascu, I.; Paunescu, A. The application of essential oils as a next-generation of pesticides: Recent developments and future perspectives. Z. Naturforsch. C 2020, 75, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Essential Oils as Ecofriendly Biopesticides? Challenges and Constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, D.; Scortichini, S.; Bonacucina, G.; Greco, N.G.; Mazzara, E.; Petrelli, R.; Torresi, J.; Maggi, F.; Cespi, M. Cannabidiol-enriched hemp essential oil obtained by an optimized microwave-assisted extraction using a central composite design. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 154, 112688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, J.K. Multiple functions of inducible plant volatiles. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaya, E.; Rafaeli, A. Essential oils as biorational insecticides-potency and mode of action. In Insecticides Design Using Advanced Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhifi, W.; Bellili, S.; Jazi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Mnif, W. Essential Oils’ Chemical Characterization and Investigation of Some Biological Activities: A Critical Review. Medicines 2016, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vickers, C.E.; Bongers, M.; Liu, Q.; Delatte, T.; Bouwmeester, H. Metabolic engineering of volatile isoprenoids in plants and microbes. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1753–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotsing Yannick Stephane, F.; Kezetas Jean Jules, B. Terpenoids as Important Bioactive Constituents of Essential Oils. In Essential Oils—Bioactive Compounds, New Perspectives and Applications; de Oliveira, M.S., da Costa, W.A., Silva, S.G., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Al Ahl, H.A.H.; Hikal, W.M.; Tkachenco, K.G. Essential Oils with Potential as Insecticidal Agents: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, R. Essential oils for the development of eco-friendly mosquito larvicides: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedini, S.; Farina, P.; Conti, B. Bioattività degli oli essenziali: Luci e ombre del loro utilizzo nella gestione degli insetti dannosi. In Atti dell’Accademia Nazionale Italiana di Entomologia; Accademia Nazionale Italiana di Entomologia: Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sánchez, G.; Sanz-Berzosa, I.; Casaña-Giner, V.; Primo-Yúfera, E. Attractiveness for Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Dipt., Tephritidae) of mango (Mangifera indica, cv. Tommy Atkins) airborne terpenes. J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A.; Van Nieuwenhove, G.; Van Nieuwenhove, C.; Rull, J. Biopesticide effects on pupae and adult mortality of Anastrepha fraterculus and Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Austral Entomol. 2018, 57, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, R.; Shelly, T.E.; Whittier, T.S.; Kaneshiro, K.Y. α-Copaene, a potential rendezvous cue for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata? J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.; Dang, C.; Kennelly, S. Exposure to orange (Citrus sinensis L.) trees, fruit, and oil enhances mating success of male Mediterranean fruit flies (Ceratitis capitata [Wiedemann]). J. Insect Behav. 2004, 17, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, D.F.; Belliard, S.A.; Vera, M.T.; Bachmann, G.E.; Ruiz, M.J.; Jofre-Barud, F.; Fernández, P.C.; López, M.L.; Shelly, T.E. Plant Chemicals and the Sexual Behavior of Male Tephritid Fruit Flies. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2018, 111, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Gruľová, D.; Baranová, B.; Caputo, L.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Antimicrobial Activity and Chemical Composition of Essential Oil Extracted from Solidago canadensis L. Growing Wild in Slovakia. Molecules 2019, 24, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sumalan, R.M.; Alexa, E.; Popescu, I.; Negrea, M.; Radulov, I.; Obistioiu, D.; Cocan, I. Exploring Ecological Alternatives for Crop Protection Using Coriandrum sativum Essential Oil. Molecules 2019, 24, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isman, M.B. Commercial development of plant essential oils and their constituents as active ingredients in bioinsecticides. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikbal, C.; Pavela, R. Essential oils as active ingredients of botanical insecticides against aphids. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, N.G.; Boukouvala, M.C.; Ntalli, N.; Skourti, A.; Karagianni, E.S.; Nika, E.P.; Kontodimas, D.C.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; Cianfaglione, K.; et al. Effectiveness of eight essential oils against two key stored-product beetles, Prostephanus truncatus (Horn) and Trogoderma granarium Everts. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 139, 111255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R.; Cianfaglione, K.; Sender, J.; Danuta, U.; Maślanko, W.; Canale, A.; Barboni, L.; Petrelli, R.; Zeppa, L.; et al. Ascaridole-rich essential oil from marsh rosemary (Ledum palustre) growing in Poland exerts insecticidal activity on mosquitoes, moths and flies without serious effects on non-target organisms and human cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R.; Drenaggi, E.; Desneux, N.; Maggi, F. Phytol, (E)-nerolidol and spathulenol from Stevia rebaudiana leaf essential oil as effective and eco-friendly botanical insecticides against Metopolophium dirhodum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 155, 112844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R.; Rakotosaona, R.; Nzekoue, F.K.; Canale, A.; Nicoletti, M.; Maggi, F. Insecticidal and mosquito repellent efficacy of the essential oils from stem bark and wood of Hazomalania voyronii. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.L.; Cho, I.L.K.; Li, Q.X. Insecticidal activity of basil oil, trans-anethole, estragole, and linalool to adult fruit flies of Ceratitis capitata, Bactrocera dorsalis, and Bactrocera cucurbitae. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A.; Van Nieuwenhove, G.; Van Nieuwenhove, C.; Rull, J. Exposure to essential oils and ethanol vapors affect fecundity and survival of two frugivorous fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) pest species. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2020, 110, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Lo Verde, G.; Sinacori, M.; Maggi, F.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; Vittori, S.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Fofie, N.G.B.Y.; Benelli, G. Developing green insecticides to manage olive fruit flies? Ingestion toxicity of four essential oils in protein baits on Bactrocera oleae. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 143, 111884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Canale, A.; Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Demi, F.; Ceccarini, L.; Macchia, M.; Conti, B. Biotoxicity of Melaleuca alternifolia (Myrtaceae) essential oil against the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae), and its parasitoid Psyttalia concolor (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Flamini, G.; Canale, A.; Cioni, P.L.; Conti, B. Toxicity of some essential oil formulations against the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera Tephritidae). Crop Prot. 2012, 42, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Turlings, T.C.J. Plant Volatiles as Mate-Finding Cues for Insects. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, R.L. Chemical Ecology of Dacinae Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1990, 83, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.E. Exposure to α-Copaene and α-Copaene-Containing Oils Enhances Mating Success of Male Mediterranean Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2001, 94, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.E.; Pahio, E. Relative Attractiveness of Enriched Ginger Root Oil And Trimedlure to Male Mediterranean Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fla. Entomol. 2002, 85, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.; Lusby, W.R.; Waters, R.M. Optical Isomers of α-Copaene Derived from Several Plant Sources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flath, R.A.; Cunningham, R.T.; Mon, T.R.; John, J.O. Male lures for Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata Wied.): Structural analogs of α-copaene. J. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 20, 2595–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.T.; Shelly, T.E.; Niyazi, N.; Jang, E. Olfactory and Behavioral Mechanisms Underlying Enhanced Mating Competitiveness Following Exposure to Ginger Root Oil and Orange Oil in Males of the Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Insect Behav. 2006, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, D.; Eberhard, W. Todd Shelly Male Courtship Behavior in Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) That Have Received Aromatherapy with Ginger Root Oil on JSTOR. Fla. Entomol. 2007, 90, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.E. Exposure to Grapefruits and Grapefruit Oil Increases Male Mating Success in the Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Proc. Hawaiian Entomol. Soc. 2009, 41, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Niogret, J.; Gill, M.A.; Espinoza, H.R.; Lima, L.; Paul Kendra, H.E.; Epsky, N.D.; Jerome Niogret, C.; Espinoza, H.R.; Kendra, P.E. Attraction and electroantennogram responses of male Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) to six plant essential oils. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5, 958–964. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.R.; Landolt, P.J.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Chambers, D.L.; Murphy, R.E.; Doolittle, R.E.; Dueben, B.D.; Sivinski, J.; Calkins, C.O. Analysis, synthesis, formulation, and field testing of three major components of male Mediterranean fruit fly pheromone. J. Chem. Ecol. 1991, 17, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howse, P.E.; Knapp, J.J. Pheromones of Mediterranean fruit fly: Presumed mode of action and implications for improved trapping techniques. In Fruit Fly Pests: A World Assessment of Their Biology and Management; McPheron, B.A., Steck, G.J., Eds.; St. Lucie Press: Delray Beach, FL, USA, 1996; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kouloussis, N.A.; Katsoyannos, B.I.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Ioannou, C.S.; Iliadis, I.V. Enhanced mating competitiveness of Ceratitis capitata males following exposure to citrus compounds. J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilici, S.; Schmitt, C.; Vidal, J.; Franck, A.; Deguine, J.P. Adult diet and exposure to semiochemicals influence male mating success in Ceratitis rosa (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.T.; Ruiz, M.J.; Oviedo, A.; Abraham, S.; Mendoza, M.; Segura, D.F.; Kouloussis, N.A.; Willink, E. Fruit compounds affect male sexual success in the South American fruit fly, Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, G.E.; Segura, D.F.; Devescovi, F.; Juárez, M.L.; Ruiz, M.J.; Vera, M.T.; Cladera, J.L.; Teal, P.E.A.; Fernández, P.C. Male sexual behavior and pheromone emission is enhanced by exposure to guava fruit volatiles in Anastrepha fraterculus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morató, S.; Shelly, T.; Rull, J.; Aluja, M. Sexual competitiveness of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae) males exposed to Citrus aurantium and Citrus paradisi essential oils. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.; Rivera, J.P.; Hernandez, E.; Montoya, P. The Effect of Ginger Oil on the Sexual Performance of Anastrepha Males (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fla. Entomol. 2011, 94, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alfonso, I.; Vacas, S.; Primo, J. Role of α-copaene in the susceptibility of olive fruits to Bactrocera oleae (Rossi). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 11976–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.I.; Vásquez, L.J.; Manzano, M.A.; Compagnone, R.S. Essential oil composition of Croton cuneatus and Croton malambo growing in Venezuela. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracho, R.; Crowley, K.J. The essential oils of some Venezuelan Croton species. Phytochemistry 1966, 5, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bin Jantan, I.; Ayop, N.; Hiong, A.B.; Ahmad, A.S. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Cinnamomum cordatum Kosterm. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutabl, E.A.; El Tohamy, S.F.; De Footer, H.L.; De Buyck, L.F. A comparative study of the essential oils from three Melaleuca species growing in Egypt. Flavour Fragr. J. 1991, 6, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, R.S.; Shalaby, A.S.; El-Baroty, G.A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Ali, M.A.; Hassan, E.M. Chemical and Biological Evaluation of the Essential Oils of Different Melaleuca Species. Phyther. Res. 2004, 18, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.J.; Lassak, E.V. Melaleuca leucadendra L. leaf oil: Two phenylpropanoid chemotypes. Flavour Fragr. J. 1988, 3, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.G.V.; Zago, H.B.; Júnior, H.J.G.S.; Da Camara, C.A.G.; De Oliveira, J.V.; Barros, R.; Schwartz, M.O.E.; Lucena, M.F.A. Composition and insecticidal activity of the essential oil of Croton grewioides Baill. against Mexican Bean Weevil (Zabrotes subfasciatus Boheman). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2008, 20, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.O.; Maciarello, M.J.; Adams, R.P.; Landrum, L.R.; Zanoni, T.A. Volatile leaf oils of caribbean myrtaceae. I. Three varieties of Pimenta racemosa (Miller) J. Moore of the Dominican Republic and the commercial bay oil. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1991, 3, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C.; Hör, K.; Weckerle, B.; König, T.; Schreier, P. Authenticity assessment of estragole and methyl eugenol by on-line gas chromatography-isotope ratio mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, O.G.S.; Andrade, L.H.A. Database of the amazon aromatic plants and their essential oils. Quim. Nova 2009, 32, 595–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howlett, F.M., VII. The effect of Oil of Citronella on two species of Dacus. Trans. R. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 2009, 60, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitt, G.P. Responses By Female Dacinae to “Male” Lures and Their Relationship to Patterns of Mating Behaviour and Pheromone Response. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1981, 29, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.E.; Dewire, A.-L.M. Chemically Mediated Mating Success in Male Oriental Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1994, 87, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, R.; Tan, K.H.; Serit, M.; Lajis, N.H.; Sukari, A.M.; Takahashi, S.; Fukami, H. Accumulation of phenylpropanoids in the rectal glands of males of the Oriented fruit fly, Dacus dorsalis. Experentia 1988, 6, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, A.K.W.; Tan, K.H. Male sex pheromonal components derived from methyl eugenol in the haemolymph of the fruit fly Bactrocera papayae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004, 30, 2127–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.K.; Nishida, R. Ecological significance of male attractant in the defence and mating strategies of the fruit fly, Bactrocera papayae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1998, 89, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.L.; Tan, K.H.; Nishida, R. Pharmacophagy of methyl eugenol by males enhances sexual selection of Bactrocera carambolae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2007, 33, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, S.L.; Tan, K.H. Female sexual response to male rectal volatile constituents in the fruit fly, Bactrocera carambolae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2005, 40, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tokushima, I.; Orankanok, W.; Tan, K.H.; Ono, H.; Nishida, R. Accumulation of Phenylpropanoid and Sesquiterpenoid Volatiles in Male Rectal Pheromonal Glands of the Guava Fruit Fly, Bactrocera correcta. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, S.L.; Abdul Munir, M.Z.; Hee, A.K.W. Attraction and consumption of methyl eugenol by male Bactrocera umbrosa Fabricius (Diptera: Tephritidae) promotes conspecific sexual communication and mating performance. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2018, 108, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, S.; Clarke, A.R. Spatial and temporal partitioning of behaviour by adult dacines: Direct evidence for methyl eugenol as a mate rendezvous cue for Bactrocera cacuminata. Physiol. Entomol. 2003, 28, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, M.T.; Kitching, W. Chemistry of Fruit Flies. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 789–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, S.; Clarke, A.R.; Yuval, B. Investigation of the Physiological Consequences of Feeding on Methyl Eugenol by Bactrocera cacuminata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, R.L.; Metcalf, E.R. Plant Kairomones in Insect Ecology and Control; Chapman and Hall Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.H.; Nishida, R.; Jang, E.B.; Shelly, T.E. Pheromones, male lures, and trapping of tephritid fruit flies. In Trapping and the Detection, Control, and Regulation of Tephritid Fruit Flies: Lures, Area-Wide Programs, and Trade Implications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 15–74. ISBN 9789401791939. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, R.; Iwahashi, O.; Tan, K.H. Accumulation of Dendrobium superbum (Orchidaceae) fragrance in the rectal glands by males of the melon fly, Dacus cucurbitae. J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, N.; Hayes, R.A.; Clarke, A.R. Cuelure but not zingerone make the sex pheromone of male Bactrocera tryoni (Tephritidae: Diptera) more attractive to females. J. Insect Physiol. 2014, 68, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumaran, N.; Balagawi, S.; Schutze, M.K.; Clarke, A.R. Evolution of lure response in tephritid fruit flies: Phytochemicals as drivers of sexual selection. Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagalingham, K. Functional Significance of Male Attractants of Bactrocera tryoni (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Underlying Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mazomenos, B.E.; Haniotakis, G.E. A multicomponent female sex pheromone of Dacus oleae Gmelin: Isolation and bioassay. J. Chem. Ecol. 1981, 7, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpati, M.L.; Lo Scalzo, R.; Vita, G. Olea europaea Volatiles attractive and repellent to the olive fruit fly (Dacus oleae, Gmelin). J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkari, A.I.; Pliakou, O.D.; Floros, G.D.; Kouloussis, N.A.; Koveos, D.S. Effect of fruit volatiles and light intensity on the reproduction of Bactrocera (Dacus) oleae. J. Appl. Entomol. 2017, 141, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, M.; Ono, H.; Wee, S.L.; Tan, H.; Nishida, R.; Hak, T.; Co, H.; Bahru, J. Floral Synomone Diversification of Bulbophyllum Sibling Species (Orchidaceae) in Attracting Fruit Fly Pollinators. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2018, 81, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khoo, C.C.H.; Tan, K.H. Attraction of both sexes of melon fly, Bactrocera cucurbitae to conspecific males–A comparison after pharmacophagy of cue-lure and a new attractant-Zingerone. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2000, 97, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, J.R.; Shelly, T.E.; Vargas, R.I.; Spafford, H. Zingerone Feeding Affects Mate Choice but not Fecundity or Fertility in the Melon Fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Fla. Entomol. 2019, 102, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, N.; Prentis, P.J.; Mangalam, K.P.; Schutze, M.K.; Clarke, A.R. Sexual selection in true fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae): Transcriptome and experimental evidences for phytochemicals increasing male competitive ability. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 4645–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shamshir, R.A.; Wee, S.L. Zingerone improves mating performance of Zeugodacus tau (Diptera: Tephritidae) through enhancement of male courtship activity and sexual signaling. J. Insect Physiol. 2019, 119, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.; Stuart, A.E.; Estambale, B.A. The repellent and antifeedant activity of Myrica gale oil against Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and its enhancement by the addition of salicyluric acid. J. R. Coll Physicians Edinb. 2003, 33, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Choochote, W.; Chaithong, U.; Kamsuk, K.; Jitpakdi, A.; Tippawangkosol, P.; Tuetun, B.; Champakaew, D.; Pitasawat, B. Repellent activity of selected essential oils against Aedes aegypti. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Ma, Y.P.; Zhang, H.X.; Sun, H.Z.; Su, H.H.; Pei, S.J.; Du, Z.Z. Repellent, larvicidal and adulticidal activities of essential oil from Dai medicinal plant Zingiber cassumunar against Aedes albopictus. Plant Divers. 2021, 43, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Feng, Y.; Du, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Borjigidai, A.; Zhang, X.; Du, S.S. Insecticidal and repellent activity of Thymus quinquecostatus Celak. essential oil and major compositions against three stored-product insects. Chem. Biodivers. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Guo, S.-S.; Lu, L.; Li, D.; Liang, J.; Huang, Z.-H.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Zhang, W.-J.; Du, S. Essential oil from Artemisia annua aerial parts: Composition and repellent activity against two storage pests. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilinger, D.; Wille, C.L.; da Rosa, J.M.; Franco, C.R.; Boff, M.I.C. Mortality Assessment of Botanical Oils on Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann, 1830) Applied in Fruits Under Laboratory Conditions. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, Y.; Heather, N.; Hassan, E. Repellency and oviposition deterrence effects of plant essential and vegetable oils against female Queensland fruit fly Bactrocera tryoni (Froggatt) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Aust. J. Entomol. 2013, 52, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S.B.; López, M.L.; Aragón, L.M.; Tereschuk, M.L.; Slanis, A.C.; Feresin, G.E.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Tapia, A.A. Composition and anti-insect activity of essential oils from Tagetes L. species (Asteraceae, Helenieae) on Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann and Triatoma infestans Klug. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5286–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, N.; De Cristofaro, A.; Maltese, M.; Vitigliano, S.; Caleca, V. First data on the repellent activity of essential oils of Citrus limon towards medfly (Ceratitis capitata). New Medit. 2012, 11, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Papanastasiou, S.A.; Ioannou, C.S.; Papadopoulos, N.T. Oviposition-deterrent effect of linalool—A compound of citrus essential oils—On female Mediterranean fruit flies, Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 3066–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.; Azhar, H.; Khan, A.; Qadir, A. Effect of Leaf Extracts of some Indigenous Plants on Settling and Oviposition Responses of Peach Fruit Fly, Bactrocera zonata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pak. J. Zool. 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, J.; Jilani, G.; Ajab Khan, M.; Masih, R.; Kanvil, S. Repellent and Oviposition Deterrent Effects of Indigenous Plant Extracts to Peach Fruit Fly, Bactrocera zonata Saunders (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pak. J. Zool. 2009, 41, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rehman, J.; Wang, X.; Johnson, M.W.; Daane, K.M.; Jilani, G.; Khan, M.A.; Zalom, F.G. Effects of Peganum harmala (Zygophyllaceae) Seed Extract on the Olive Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Its Larval Parasitoid Psyttalia concolor (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, A.; Jilani, G.; Rehman, J.; Kanvil, S. Effect of turmeric extracts on settling response and fecundity of peach fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pak. J. Zool. 2006, 38, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel, W.; Wang, D.; Lei, Y.; Qi, G.; Chen, T.; Rizvi, S.A.H.; Sethuraman, V.; He, Y.; Lu, L. Evaluating the repellent effect of four botanicals against two Bactrocera species on mangoes. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.-C.; Dong, Y.-J.; Cheng, L.-L.; Houl, R.F. Horticultural entomology Deterrent Effect of Neem Seed Kernel Extract on Oviposition of the Oriental Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Guava. J. Econ. Entomol. 1996, 89, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, R.P. Neem (Azadirachta indica) seed kernel extracts and azadirachtin as oviposition deterrents against the melon fly (Bactrocera cucurbitae) and the oriental fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis). Phytoparasitica 1998, 26, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P.; Hu, M.; Zhong, G. Bdor\Orco is important for oviposition-deterring behavior induced by both the volatile and non-volatile repellents in Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Insect Physiol. 2014, 65, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, S.A.; Bali, E.M.D.; Ioannou, C.S.; Papachristos, D.P.; Zarpas, K.D.; Papadopoulos, N.T. Toxic and hormetic-like effects of three components of citrus essential oils on adult Mediterranean fruit flies (Ceratitis capitata). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ioannou, C.S.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Kouloussis, N.A.; Tananaki, C.I.; Katsoyannos, B.I. Essential oils of citrus fruit stimulate oviposition in the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Physiol. Entomol. 2012, 37, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, D.P.; Kimbaris, A.C.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Polissiou, M.G. Toxicity of citrus essential oils against Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) larvae. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2009, 155, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothon, F.T.D.; Gnanvossou, D.; Noudogbessi, J.P.; Hanna, R.; Sohounhloue, D. Bactrocera cucurbitae response to four Cymbopogon species essential oils. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 6, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Campolo, O.; Giunti, G.; Russo, A.; Palmeri, V.; Zappalà, L. Essential Oils in Stored Product Insect Pest Control. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 6906105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isman, M.B.; Miresmailli, S.; MacHial, C. Commercial opportunities for pesticides based on plant essential oils in agriculture, industry and consumer products. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottakina Akter, M. The effects of methyl eugenol, cue lure and plant essential oils in rubber foam dispenser for controlling Bactrocera dorsalis and Zeugodacus cucurbitae. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.J.S.; Murcia, A.; Wanumen, A.C.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Teixeira, Á.A.C.; Ortiz, A.; Medina, P. Composition and Toxicity of a Mixture of Essential Oils Against Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdoub, K.; Benomari, F.Z.; Djabou, N.; Dib, M.E.A.; Benyelles, N.G.; Costa, J.; Muselli, A. Antifungal and insecticidal activities of essential oils of four Mentha species. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2019, 14, e64165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.S.; Iijima, A.; Huang, J.; Li, Q.X.; Chen, Y. Putative Mode of Action of the Monoterpenoids Linalool, Methyl Eugenol, Estragole, and Citronellal on Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Engineering 2020, 6, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamraoui, A.; Regnault-Roger, C. Comparaison des activités insecticides des monoterpènes sur deux espèces d’insectes ravageurs des cultures: Ceratitis capitata et Rhopalosiphum padi. Acta Bot. Gall. 1997, 144, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Sabier, M.; Zhang, T.; Deng, J.; Song, X.; Liao, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Cao, Y.; et al. Trans-anethole is a potent toxic fumigant that partially inhibits rusty grain beetle (Cryptolestes ferrugineus) acetylcholinesterase activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 161, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Luca, V.S.; Trifan, A.; Miron, A. Antigenotoxic Potential of Some Dietary Non-phenolic Phytochemicals. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; ur-Rahman, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 60, pp. 223–297. [Google Scholar]

- Khoobdel, M.; Ahsaei, S.M.; Farzaneh, M. Insecticidal activity of polycaprolactone nanocapsules loaded with Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil in Tribolium castaneum (Herbst). Entomol. Res. 2017, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainane, A.; Khammour, F.; Charaf, S.; Elabboubi, M.; Elkouali, M.; Talbi, M.; Benhima, R.; Cherroud, S.; Ainane, T. Chemical composition and insecticidal activity of five essential oils: Cedrus atlantica, Citrus limonum, Rosmarinus officinalis, Syzygium aromaticum and Eucalyptus globules. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 13, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J.H.; Jovel, E.; Isman, M.B. Comparative and synergistic activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil constituents against the larvae and an ovarian cell line of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Harbi, N.A.; Al Attar, N.M.; Hikal, D.M.; Mohamed, S.E.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Abdein, M.A. Evaluation of insecticidal effects of plants essential oils extracted from basil, black seeds and lavender against Sitophilus oryzae. Plants 2021, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.J.; Juárez, M.L.; Alzogaray, R.A.; Arrighi, F.; Arroyo, L.; Gastaminza, G.; Willink, E.; Bardón, A.D.V.; Vera, T. Toxic effect of citrus peel constituents on Anastrepha fraterculus Wiedemann and Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann immature stages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10084–10091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senouci, H.; Benyelles, N.G.; Dib, M.E.; Costa, J.; Muselli, A. Ammoides verticillata Essential Oil as Biocontrol Agent of Selected Fungi and Pest of Olive Tree. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2019, 11, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.E.; Pereira, R.M.; Koehler, P.G. Complications with Controlling Insect Eggs. In Insecticides Resistance; Trdan, S., Ed.; InTech Open: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Campolo, O.; Cherif, A.; Ricupero, M.; Siscaro, G.; Grissa-Lebdi, K.; Russo, A.; Cucci, L.M.; Di Pietro, P.; Satriano, C.; Desneux, N.; et al. Citrus peel essential oil nanoformulations to control the tomato borer, Tuta absoluta: Chemical properties and biological activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfara, V.; Zerba, E.N.; Alzogaray, R.A. Fumigant insecticidal activity and repellent effect of five essential oils and seven monoterpenes on first-instar nymphs of Rhodnius prolixus. J. Med. Entomol. 2009, 46, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, G.H.A. Insecticidal and acaricidal activity of carvacrol and β-thujaplicine derived from Thujopsis dolabrata var. hondai sawdust. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanikor, B.; Parida, P.; Yadav, R.N.S.; Bora, D. Comparative mode of action of some terpene compounds against octopamine receptor and acetyl cholinesterase of mosquito and human system by the help of homology modeling and docking studies. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Minshawy, A.M.; Abdelgaleil, S.A.M.; Gadelhak, G.G.; AL-Eryan, M.A.; Rabab, R.A. Effects of monoterpenes on mortality, growth, fecundity, and ovarian development of Bactrocera zonata (Saunders) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 15671–15679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischof, L.J.; Enan, E.E. Cloning, expression and functional analysis of an octopamine receptor from Periplaneta americana. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 34, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enan, E. Insecticidal activity of essential oils: Octopaminergic sites of action. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2001, 130, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enan, E.E. Molecular response of Drosophila melanogaster tyramine receptor cascade to plant essential oils. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 35, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, C.M.; Williamson, E.M.; Wafford, K.A.; Sattelle, D.B. Thymol, a constituent of thyme essential oil, is a positive allosteric modulator of human GABA A receptors and a homo-oligomeric GABA receptor from Drosophila melanogaster. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 140, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amos, T.G.; Williams, P.; Du Guesclin, P.B.; Schwarz, M. Compounds Related to Juvenile Hormone: Activity of Selected Terpenoids on Tribolium castaneum and T. confusum. J. Econ. Entomol. 1974, 67, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamopoulos, D.C.; Damos, P.; Karagianidou, G. Bioactivity of five monoterpenoid vapours to Tribolium confusum (du Val) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2007, 43, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Sriranjini, V. Plant products as fumigants for stored-product insect control. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2008, 44, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.D.; Baxendale, F. Toxicity of Seven Monoterpenoids to Tracheal Mites (Acari: Tarsonemidae) and Their Honey Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Hosts When Applied as Fumigants. J. Econ. Entomol. 1997, 90, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Kouloussis, N.; Katsoyannos, B. Effect of plant chemicals on the behavior of the Mediterranean fruit fly. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposioum on Fruit Flies of Economic Importance, Salvador, Brazil, 10–15 September 2006; pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, I.S.; House, P.E.; Do Nascimento, R.R. Volatile Substances from Male Anastrepha fraterculus Wied. (Diptera: Tephritidae): Identification and Behavioural Activity. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2001, 12, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.B.; Silva, C.E.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Dos Santos, E.S.; Do Nascimento, R.R.; Da Silva, E.L.; Mendonça, A.D.; De Freitas, M.D.; Sant’Ana, A.E. Comparison of the Volatile Components Released by Calling Males of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) with Those Extractable from The Salivary Glands. Fla. Entomol. 2006, 89, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofré Barud, F.; López, S.; Tapia, A.; Feresin, G.E.; López, M.L. Attractant, sexual competitiveness enhancing and toxic activities of the essential oils from Baccharis spartioides and Schinus polygama on Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdelas, R.R.; López, S.; Lima, B.; Feresin, G.E.; Zygadlo, J.; Zacchino, S.; López, M.L.; Tapia, A.; Freile, M.L. Chemical composition, anti-insect and antimicrobial activity of Baccharis darwinii essential oil from Argentina, Patagonia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 40, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S.; Lima, B.; Aragón, L.; Espinar, L.A.; Tapia, A.; Zacchino, S.; Zygadlo, J.; Feresin, G.E.; López, M.L. Essential oil of Azorella cryptantha collected in two different locations from San Juan Province, argentina: Chemical variability and anti-insect and Antimicrobial Activities. Chem. Biodivers. 2012, 9, 1452–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Koul, O.; Rup, P.J.; Jindal, J. Toxicity of some essential oil constituents and their binary mixtures against Chilo partellus (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2009, 29, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Singh, H.; Mehta, N.; Rath, S.S. In vitro assessment of synergistic combinations of essential oils against Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp. Parasitol. 2019, 201, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, A.; Picollo, M.I.; González-Audino, P.; Mougabure-Cueto, G. Insecticidal activity of individual and mixed monoterpenoids of geranium essential oil against Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koul, O.; Singh, R.; Kaur, B.; Kanda, D. Comparative study on the behavioral response and acute toxicity of some essential oil compounds and their binary mixtures to larvae of Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura and Chilo partellus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Chen, W.; Isman, M.B. Synergism of malathion and inhibition of midgut esterase activities by an extract from Melia toosendan (Meliaceae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1995, 53, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.J.S.; Murcia-Meseguer, A.; Azpiazu, C.; Wanumen, A.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Teixeira, Á.A.C.; Ortiz, A.; Medina, P. Side effects of a mixture of essential oils on Psyttalia concolor. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, V.; Karpouhtsis, I.; Franzios, G.; Zambetaki, A.; Scouras, Z.; Mavragani-Tsipidou, P. Insecticidal and Genotoxic Effects of Essential Oils of Greek sage, Salvia fruticosa, and Mint, Mentha pulegium, on Drosophila melanogaster and Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Agric. Urban Entomol. 2004, 21, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dorla, E.; Gauvin-Bialecki, A.; Deuscher, Z.; Allibert, A.; Grondin, I.; Deguine, J.-P.; Laurent, P. Insecticidal Activity of the Leaf Essential Oil of Peperomia borbonensis Miq. (Piperaceae) and Its Major Components against the Melon Fly Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelli, G.; Rizzo, R.; Zeni, V.; Govigli, A.; Samková, A.; Sinacori, M.; Lo Verde, G.; Pavela, R.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; et al. Carlina acaulis and Trachyspermum ammi essential oils formulated in protein baits are highly toxic and reduce aggressiveness in the medfly, Ceratitis capitata. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 161, 113191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G.; Almeida, M.L.; Gonçalves, M.A.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Barroso, J.G.; Pedro, L.M. Toxic effects of three essential oils on Ceratitis capitata. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2010, 13, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passino, G.S.; Bazzoni, E.; Moretti, M.D.L.; Prota, R. Effects of essential oil formulations on Ceratitis capitata Wied. (Dipt., Tephritidae) adult flies. J. Appl. Entomol. 1999, 123, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buentello-Wong, S.; Galán-Wong, L.; Arévalo-Niño, K.; Almaguer-Cantú, V.; Rojas-Verde, G. Toxicity of some essential oil formulations against the Mexican fruit fly Anastrepha ludens (Loew) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 85, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R.; Petrelli, R.; Nzekoue, F.K.; Cappellacci, L.; Lupidi, G.; Quassinti, L.; Bramucci, M.; Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; et al. Carlina oxide from Carlina acaulis root essential oil acts as a potent mosquito larvicide. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, D.A. Medicinal plants polyacetylene compounds of plants of the Asteraceae family (review). Pharm. Chem. J. 2014, 48, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyzewska, M.M.; Chrobok, L.; Kania, A.; Jatczak, M.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Mozrzymas, J.W. Dietary acetylenic oxylipin falcarinol differentially modulates GABAA receptors. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, H.Z.; Levinson, A.R.; Müller, K. Influence of some olfactory and optical properties of fruits on host location by the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata Wied.). J. Appl. Entomol. 1990, 109, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoyannos, B.I.; Kouloussis, N.A.; Papadopoulos, N.T. Response of Ceratitis capitata to citrus chemicals under semi-natural conditions. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1997, 82, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.T.; Katsoyannos, B.I.; Kouloussis, N.A.; Hendrichs, J. Effect of orange peel substances on mating competitiveness of male Ceratitis capitata. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2001, 99, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shazly, A.M.; Hussein, K.T. Chemical analysis and biological activities of the essential oil of Teucrium leucocladum Boiss. (Lamiaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gawad, A.A.; Elshamy, A.; El Gendy, A.E.N.; Gaara, A.; Assaeed, A. Volatiles profiling, allelopathic activity, and antioxidant potentiality of Xanthium strumarium leaves essential oil from Egypt: Evidence from chemometrics analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abd El-Gawad, A.M. Chemical constituents, antioxidant and potential allelopathic effect of the essential oil from the aerial parts of Cullen plicata. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 80, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaie, H.R.; Nadjafi, F.; Bannayan, M. Effect of irrigation frequency and planting density on herbage biomass and oil production of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis). Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Rogalska, J.; Wyszkowska, J.; Stankiewicz, M. Molecular targets for components of essential oils in the insect nervous system—A review. Molecules 2018, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryan, M.F.; Byrne, O. Plant-insect co-evolution and inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. J. Chem. Ecol. 1988, 14, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.J.; Seo, H.K.; Kang, B.J.; Kim, K.T. Non competitive inhibition by camphor of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001, 61, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.; Cleary, B.V.; Walsh, J.J.; Gilmer, J.F. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by Tea Tree oil. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004, 56, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Yamafuji, C. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity by tea tree oil and constituent terpenoids. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Yamafuji, C. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity by bicyclic monoterpenoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1765–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.D.; Campoy, F.J.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J.; Muñoz-Delgado, E.; Vidal, C.J. Acetylcholinesterase activity of electric eel is increased or decreased by selected monoterpenoids and phenylpropanoids in a concentration-dependent manner. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 229, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A.; Coats, J.R. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by nootkatone and carvacrol in arthropods. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 102, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg-Levy, S.H.; Kostjukovsky, M.; Ravid, U.; Shaaya, E. Studies to elucidate the effect of monoterpenes on acetylcholinesterase in two stored-product insects. Acta Hortic. 1993, 344, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.D.; Pascual-Villalobos, M.J. Mode of inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by monoterpenoids and implications for pest control. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F. Investigation of Mechanisms of Action of Monoterpenoid Insecticides on Insect GAMMA-Aminobutyric Acid Receptors and Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Ph.D. Thesis, Lowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, F.; Coats, J.R. Effects of monoterpenoid insecticides on [3H]-TBOB binding in house fly GABA receptor and Cl- uptake in American cockroach ventral nerve cord. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2010, 98, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomquist, J.R.; Boina, D.R.; Chow, E.; Carlier, P.R.; Reina, M.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A. Mode of action of the plant-derived silphinenes on insect and mammalian GABAA receptor/chloride channel complex. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2008, 91, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]