Effects of Bilberry Supplementation on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

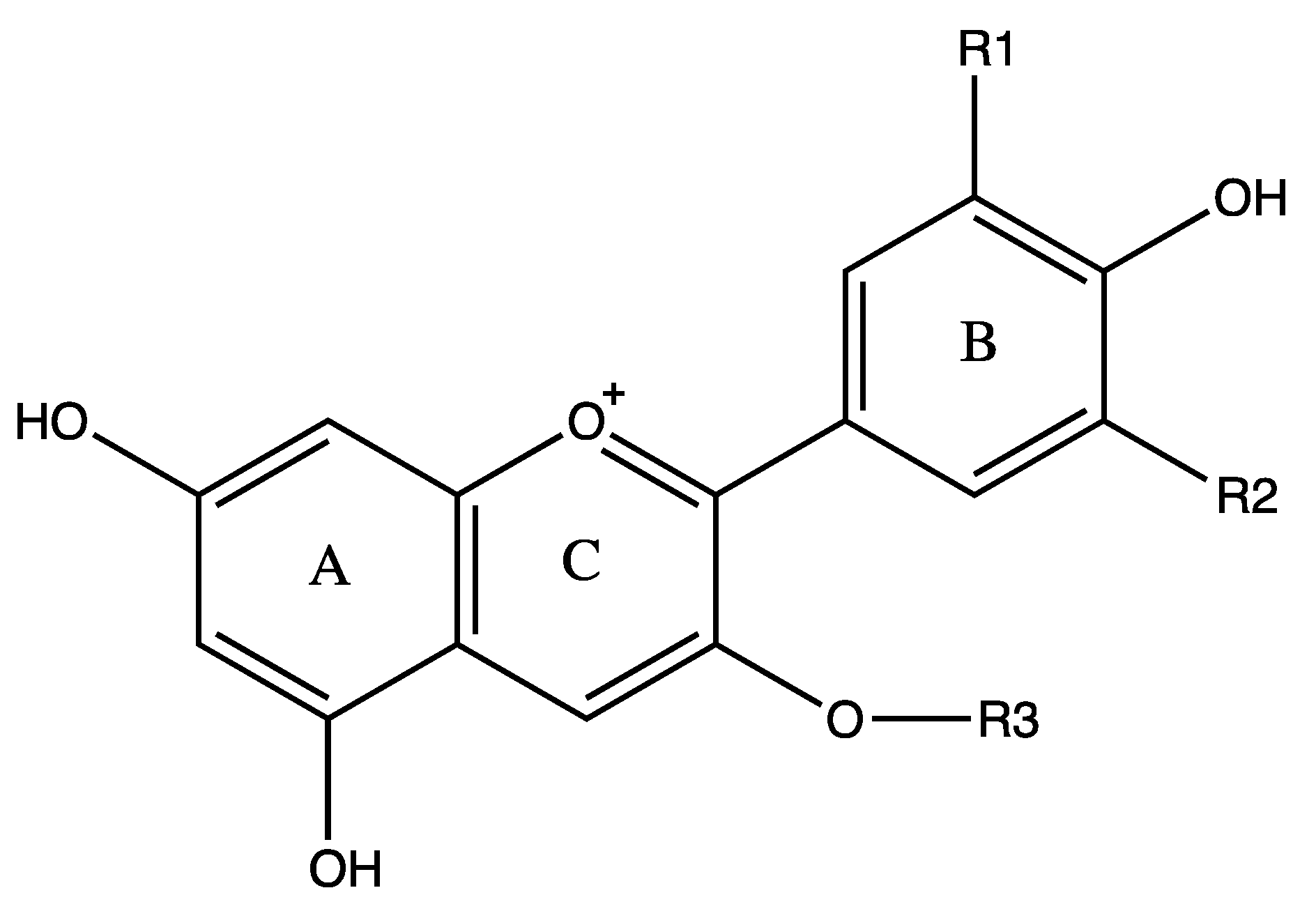

2. Chemical Structure, Distribution and Bioavailability of Anthocyanins

3. Beneficial Effects of Bilberries

3.1. Antioxidant Effect

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effect

3.3. Hypoglycemic Effect

3.4. Effect on Dyslipidemia

4. Adverse Effects of Bilberry

5. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CADP-CT | closing time in platelet function analyzer with collagen and ADP |

| CETP | cholesteryl ester transfer protein |

| FMD | flow-mediated dilation |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| hsCRP | high-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-κB |

| PFA-100 CTs | Platelet Function Analyzer-100 closure times |

| sVCAM-1 | soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

References

- Monteiro, R.; Azevedo, I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediat. Inflamm. 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.S.; Lean, M.E.J. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Maseri, A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002, 105, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baynes, J.W. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes 1991, 40, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.S.; Harris, A.K.; Rychly, D.J.; Ergul, A. Oxidative stress and the use of antioxidants in diabetes: Linking basic science to clinical practice. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2005, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications-A unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.D.; Habib, S.L.; Abboud, H.E. Fasting serum glucose level and cancer risk in Korean men and women. JAMA 2005, 293, 2210–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandona, P.; Aljada, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Mohanty, P. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and diabetes. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2004, 5, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chan, S.W.; Hu, M.; Walden, R.; Tomlinson, B. Effects of some common food constituents on cardiovascular disease. ISRN Cardiol. 2011, 2011, 397136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.M.; Luby, J.J.; Hancock, J.F.; Berkheimer, S.; Hanson, E.J. Changes in fruit antioxidant activity among blueberry cultivars during cold-temperature storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R. Bilberry fruit Vaccinium myrtillus L. In Standards of Analysis, Quality Control, and Therapeutics; American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Compendium: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, E.; Krzesinski, P.; Kura, M.; Szmigiel, B.; Blaszczyk, J. Anthocyanins in medicine. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.K.; Cheung, S.C.M.; Lau, R.A.W.; Benzie, I.F.F. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.). In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cravotto, G.; Boffa, L.; Genzini, L.; Garella, D. Phytotherapeutics: An evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2010, 35, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.L. Anthocyanins: Structural characteristics that result in unique metabolic patterns and biological activities. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.M.; Chia, L.S.; Goh, N.K.; Chia, T.F.; Brouillard, R. Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P. Berry fruits: Compositional elements, biochemical activities, and the impact of their intake on human health, performance, and disease. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duthie, S.J.; Jenkinson, A.M.; Crozier, A.; Mullen, W.; Pirie, L.; Kyle, J.; Yap, L.S.; Christen, P.; Duthie, G.G. The effects of cranberry juice consumption on antioxidant status and biomarkers relating to heart disease and cancer in healthy human volunteers. Eur. J. Nutr. 2006, 45, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: Colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winefield, C.; Davies, K.; Gould, K. Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Bioavailability of anthocyanins. Drug Metab. Rev. 2014, 46, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Stone, S.; Yasmin, T.; Bagchi, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Vinson, J.A.; Bagchi, D. Berry anthocyanins as novel antioxidants in human health and disease prevention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.; Roy, S.; Patel, V.; He, G.L.; Khanna, S.; Ojha, N.; Phillips, C.; Ghosh, S.; Bagchi, M.; Sen, C.K. Safety and whole-body antioxidant potential of a novel anthocyanin-rich formulation of edible berries. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 281, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Cao, G.H.; Martin, A.; Sofic, E.; McEwen, J.; O’Brien, C.; Lischner, N.; Ehlenfeldt, M.; Kalt, W.; Krewer, G.; et al. Antioxidant capacity as influenced by total phenolic and anthocyanin content, maturity, and variety of Vaccinium species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozier, A.; Jaganath, I.B.; Clifford, M.N. Dietary phenolics: Chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1001–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pojer, E.; Mattivi, F.; Johnson, D.; Stockley, C.S. The case for anthocyanin consumption to promote human health: A review. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 483–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres-Lacueva, C.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Galli, R.L.; Jauregui, O.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Joseph, J.A. Anthocyanins in aged blueberry-fed rats are found centrally and may enhance memory. Nutr. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Roowi, S.; Rouanet, J.M.; Duthie, G.G.; Lean, M.E.J.; Crozier, A. The bioavallability of raspberry anthocyanins and ellagitannins in rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgines, C.; Talavera, S.; Gonthier, M.P.; Texier, O.; Scalbert, A.; Lamaison, J.L.; Remesy, C. Strawberry anthocyanins are recovered in urine as glucuro- and sulfoconjugates in humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgines, C.; Texier, O.; Besson, C.; Fraisse, D.; Lamaison, J.L.; Remesy, C. Blackberry anthocyanins are slightly bioavailable in rats. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marczylo, T.H.; Cooke, D.; Brown, K.; Steward, W.P.; Gescher, A.J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of the putative cancer chemopreventive agent cyanidin-3-glucoside in mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009, 64, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, H.; Ogawa, T.; Koyanagi, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Goda, T.; Kumazawa, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Shimoi, K. Distribution and excretion of bilberry anthocyanins in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7681–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Remesy, C.; Jimenez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.H.; Muccitelli, H.U.; Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Prior, R.L. Anthocyanins are absorbed in glycated forms in elderly women: A pharmacokinetic study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Russell, R.M.; Lischner, N.; Prior, R.L. Serum antioxidant capacity is increased by consumption of strawberries, spinach, red wine or vitamin C in elderly women. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Kay, C.D.; Cottrell, T.; Holub, B.J. Absorption of anthocyanins from blueberries and serum antioxidant status in human subjects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7731–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold, J.A.; Loscalzo, J. Oxidative mechanisms and atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease. Drug Discov. Today Ther. Strateg. 2008, 5, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, I. Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress-A concise review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentova, K.; Ulrichova, J.; Cvak, L.; Simanek, V. Cytoprotective effect of a bilberry extract against oxidative damage of rat hepatocytes. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, R.; Marabini, L. Protective effect of Vaccinium myrtillus extract against UVA- and UVB-induced damage in a human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT Cells). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 132, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casedas, G.; Gonzalez-Burgos, E.; Smith, C.; Lopez, V.; Gomez-Serranillos, M.P. Regulation of redox status in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells by blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) juice, cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon A.) juice and cyanidin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakesevic, M.; Aaby, K.; Borge, G.I.A.; Jeppsson, B.; Ahrne, S.; Molin, G. Antioxidative protection of dietary bilberry, chokeberry and Lactobacillus plantarum HEAL19 in mice subjected to intestinal oxidative stress by ischemia-reperfusion. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosova, N.G.; Shcheglova, T.V.; Sergeeva, S.V.; Loskutova, L.V. Long-term antioxidant supplementation attenuates oxidative stress markers and cognitive deficits in senescent-accelerated OXYS rats. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavafi, M.; Ahmadvand, H. Effect of rosmarinic acid on inhibition of gentamicin induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Tissue Cell 2011, 43, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljkovic, M.; Pavlovic, D.R.; Stojiljkovic, N.; Ilic, S.; Jovanovic, I.; Ulrih, N.P.; Rakic, V.; Velickovic, L.; Sokolovic, D. Bilberry: Chemical profiling, in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity and nephroprotective effect against gentamicin toxicity in rats. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Forney, C.F.; Martin, A.; Prior, R.L. Antioxidant capacity, vitamin C, phenolics, and anthocyanins after fresh storage of small fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4638–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marniemi, J.; Hakala, P.; Maki, J.; Ahotupa, M. Partial resistance of low density lipoprotein to oxidation in vivo after increased intake of berries. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2000, 10, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, A.; Paur, I.; Bohn, S.K.; Sakhi, A.K.; Borge, G.I.; Serafini, M.; Erlund, I.; Laake, P.; Tonstad, S.; Blomhoff, R. Bilberry juice modulates plasma concentration of NF-kappa B related inflammatory markers in subjects at increased risk of CVD. Eur. J. Nutr. 2010, 49, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevstrom, L.; Bergh, C.; Landberg, R.; Wu, H.X.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Waldenborg, M.; Magnuson, A.; Blanc, S.; Frobert, O. Freeze-dried bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) dietary supplement improves walking distance and lipids after myocardial infarction: An open-label randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Res. 2019, 62, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, J.; Rensen, S.S.; Slaats, Y.; van Dielen, F.M.; Buurman, W.A.; Greve, J.W. Neutrophil activation in morbid obesity, chronic activation of acute inflammation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009, 17, 2014–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravenec, M.; Kajiya, T.; Zidek, V.; Landa, V.; Mlejnek, P.; Simakova, M.; Silhavy, J.; Malinska, H.; Oliyarnyk, O.; Kazdova, L.; et al. Effects of human c-reactive protein on pathogenesis of features of the metabolic syndrome. Hypertension 2011, 57, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Shoelson, S.E. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziccardi, P.; Nappo, F.; Giugliano, G.; Esposito, K.; Marfella, R.; Cioffi, M.; D’Andrea, F.; Molinari, A.M.; Giugliano, D. Reduction of inflammatory cytokine concentrations and improvement of endothelial functions in obese women after weight loss over one year. Circulation 2002, 105, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Kader, S.M.; Al-Dahr, M.H.S. Impact of weight loss on oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in obese type 2 diabetic patients. Afr. Health Sci. 2016, 16, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, N.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Masoudkabir, F.; Djalali, M.; Sadrzadeh-Yeganeh, H.H.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Chamary, M.; Ahmadivand, Z.; Yazdani, T.; Javanbakht, M.H. Effect of diet-induced weight loss on inflammatory cytokines in obese women. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2013, 36, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, H.P.; Krzyzanowska, K.; Mohlig, M.; Spranger, J.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Schernthaner, G. Effects of marked weight loss on plasma levels of adiponectin, markers of chronic subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance in morbidly obese women. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostrom, C.D.; Lissner, L.; Wedel, H.; Sjostrom, L. Reduction in incidence of diabetes, hypertension and lipid disturbances after intentional weight loss induced by bariatric surgery: The SOS intervention study. Obes. Res. 1999, 7, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Sherwood, A.; Gullette, E.C.D.; Babyak, M.; Waugh, R.; Georgiades, A.; Craighead, L.W.; Tweedy, D.; Feinglos, M.; Appelbaum, M.; et al. Exercise and weight loss reduce blood pressure in men and women with mild hypertension-effects on cardiovascular, metabolic, and hemodynamic functioning. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Loscalzo, J.; Ridker, P.M.; Farkouh, M.E.; Hsue, P.Y.; Fuster, V.; Hasan, A.A.; Amar, S. Inflammation, immunity, and infection in atherothrombosis JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. A test in context: High-sensitivity c-reactive protein. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. From c-reactive protein to interleukin-6 to interleukin-1 moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. Clinician’s guide to reducing inflammation to reduce atherothrombotic risk JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3320–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Lüscher, T.F. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. Anticytokine agents targeting interleukin signaling pathways for the treatment of atherothrombosis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. Anti-inflammatory therapy for atherosclerosis: Interpreting divergent results from the CANTOS and CIRT clinical trials. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebel, S.; Trieu, H.L.; Richling, E. Modulation of inflammatory gene expression by a bilberry ( Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract and single anthocyanins considering their limited stability under cell culture conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8902–8910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Shin, W.H.; Seo, J.W.; Kim, E.J. Anthocyanins inhibit airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine asthma model. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piberger, H.; Oehme, A.; Hofmann, C.; Dreiseitel, A.; Sand, P.G.; Obermeier, F.; Schoelmerich, J.; Schreier, P.; Krammer, G.; Rogler, G. Bilberries and their anthocyanins ameliorate experimental colitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkanen, O.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Leppanen, T.; Moilanen, E.; Adriaens, M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Hallikainen, M.; Puupponen-Pimia, R.; Pulkkinen, L.; et al. Bilberries reduce low-grade inflammation in individuals with features of metabolic syndrome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, A.; Retterstol, L.; Laake, P.; Paur, I.; Kjolsrud-Bohn, S.; Sandvik, L.; Blomhoff, R. Anthocyanins inhibit nuclear factor-kappa B activation in monocytes and reduce plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory mediators in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1951–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ling, W.; Guo, H.; Song, F.; Ye, Q.; Zou, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, R.; Vaarala, O.; Turpeinen, A.M.; Mutanen, M. No difference in platelet activation or inflammation markers after diets rich or poor in vegetables, berries and apple in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Nutr. 2004, 43, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010, 33 (Suppl. 1), S62–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrle, S.; Hsu, W.H. The etiology of oxidative stress in insulin resistance. Biomed. J. 2017, 40, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.M.; Tewari, S.; Mendes, R.H. The role of oxidative stress in the development of diabetes mellitus and its complications. J. Diabetes Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, D.; Ceriello, A.; Paolisso, G. Oxidative stress and diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Care 1996, 19, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsedek, A.; Majewska, I.; Redzynia, M.; Sosnowska, D.; Koziolkiewicz, M. In vitro inhibitory effect on digestive enzymes and antioxidant potential of commonly consumed fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4610–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.J.; Kulkarni, N.N.; Stewart, D. Current developments on the inhibitory effects of berry polyphenols on digestive enzymes. Biofactors 2008, 34, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sales, P.M.; de Souza, P.M.; Simeoni, L.A.; Magalhaes, P.D.; Silveira, D. Alpha-amylase inhibitors: A review of raw material and isolated compounds from plant source. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 15, 141–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakasam, B.; Vareed, S.K.; Olson, L.K.; Nair, M.G. Insulin secretion by bioactive anthocyanins and anthocyanidins present in fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, L.C.; Couture, A.; Spoor, D.; Benhaddou-Andaloussi, A.; Harris, C.; Meddah, B.; Leduc, C.; Burt, A.; Vuong, T.; Le, P.M.; et al. Anti-diabetic properties of the Canadian lowbush blueberry Vaccinium angustifolium Ait. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takikawa, M.; Inoue, S.; Horio, F.; Tsuda, T. Dietary anthocyanin-rich bilberry extract ameliorates hyperglycemia and insulin sensitivity via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in diabetic mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petlevski, R.; Hadzija, M.; Slijepcevic, M.; Juretic, D. Effect of ‘antidiabetis’ herbal preparation on serum glucose and fructosamine in NOD mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 75, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, A.; Nastasi, M.; Cavalli, E.; Puglisi, L. Novel lipid-lowering properties of Vaccinium myrtillus L. leaves, a traditional antidiabetic treatment, in several models of rat dyslipidaemia: A comparison with ciprofibrate. Thromb. Res. 1996, 84, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Sohn, E.; Jo, K.; Kim, J.S. Vaccinium myrtillus extract prevents or delays the onset of diabetes-induced blood-retinal barrier breakdown. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoggard, N.; Cruickshank, M.; Moar, K.M.; Bestwick, C.; Holst, J.J.; Russell, W.; Horgan, G. A single supplement of a standardised bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract (36% wet weight anthocyanins) modifies glycaemic response in individuals with type 2 diabetes controlled by diet and lifestyle. J. Nutr. Sci. 2013, 2, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xia, M.; Ma, J.; Hao, Y.T.; Liu, J.; Mou, H.; Cao, L.; Ling, W.H. Anthocyanin supplementation improves serum LDL- and HDL-cholesterol concentrations associated with the inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in dyslipidemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmo, P.S.; Kangas, A.J.; Soininen, P.; Lehtonen, H.M.; Suomela, J.P.; Yang, B.R.; Viikari, J.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Kallio, H.P. Effects of sea buckthorn and bilberry on serum metabolites differ according to baseline metabolic profiles in overweight women: A randomized crossover trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140, E596–E646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, H.N.; Zhang, Y.L.; Hernandez-Ono, A. Metabolic syndrome: Focus on dyslipidemia. Obesity 2006, 14, 41S–49S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.F.; Meigs, J.B.; Sullivan, L.; Fox, C.S.; Nathan, D.M.; D’Agostino, R.B. Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults—The Framingham Offspring Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, D.; Seifert, S.; Jaudszus, A.; Bub, A.; Watzl, B. Anthocyanin-rich juice lowers serum cholesterol, leptin, and resistin and improves plasma fatty acid composition in Fischer rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, L.; Overgaard, A.; Christensen, L.P.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Hermansen, K. Polyphenol-rich bilberry ameliorates total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol when implemented in the diet of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2013, 10, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; RafieianKopaei, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Shamsi, F.; Goli-malekabadi, N. Anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of Vaccinium myrtillus fruit in experimentally induced diabetes (antidiabetic effect of Vaccinium myrtillus fruit). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, L.; Axling, U.; Blanco, N.; Sterner, O.; Holm, C.; Berger, K. Evaluation of beneficial metabolic effects of berries in high-fat fed C57BL/6J mice. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 2014, 403041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlund, I.; Koli, R.; Alfthan, G.; Marniemi, J.; Puukka, P.; Mustonen, P.; Mattila, P.; Jula, A. Favorable effects of berry consumption on platelet function, blood pressure, and HDL cholesterol. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.N.; Xia, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.Q.; Li, Z.X.; Hao, Y.T.; Mi, M.T.; Jin, T.R.; Ling, W.H. Purified anthocyanin supplementation improves endothelial function via NO-cGMP activation in hypercholesterolemic individuals. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.N.; Huang, X.W.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, R.F.; Xia, M. Anthocyanin supplementation improves HDL-associated paraoxonase 1 activity and enhances cholesterol efflux capacity in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, L.; Mwinyi, J.; Scharl, M.; Frei, P.; Zeitz, J.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Fried, M.; Weber, A.; Humpf, H.U.; et al. Bilberry ingestion improves disease activity in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis—An open pilot study. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anthocyanin (% in Content in Bilberry) | R1 | R2 | λmax (nm) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R3=H | R3=gluc | |||

| Delphinidin (15.17%) | OH | OH | 546 | 541 |

| Cyanidin (8.36%) | OH | H | 535 | 530 |

| Petunidin (6.64%) | OH | OCH3 | 543 | 540 |

| Malvidin (5.43%) | OCH3 | OCH3 | 542 | 538 |

| Peonidin (1.87%) | OCH3 | H | 532 | 528 |

| * In methanol with 0.01% HCl. | ||||

| Authors | Type of Study | Subjects | Interventions | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant effect | ||||

| Marniemi et al. [48] | Randomized controlled trial | 60 healthy volunteers | 100 g deep-frozen berries (bilberries, lingonberries, or blackcurrants) daily for 8 weeks; 240 g berries in postprandial study; or 500 g calcium gluconate | Increased serum ascorbate, slight decrease in LDL oxidation, slight increase in serum antioxidant capacity in berry group; decreased LDL oxidation in postprandial study |

| Duthie et al. [18] | Randomized controlled trial | 20 healthy volunteers | 750 mL/day of cranberry juice (Ocean Spray Cranberry Select) or placebo drink (natural mineral water with strawberry flavor + sucrose (9 g/100mL)) for 2 weeks | No effect on blood or cellular antioxidant status, lipid status, or oxidative DNA damage between groups |

| Karlsen et al. [49] | Randomized controlled trial | 62 volunteers with increased risk of CVD | 330 mL/day bilberry juice (Corona Safteri, Rotvoll, Norway) or water for 4 weeks | No effect on antioxidant status or oxidative stress |

| Arevstrom et al. [50] | Randomized controlled trial | 50 patients who were within 24 h of percutaneous coronary intervention | Bilberry powder (40 g/d, equivalent to 480 g fresh bilberries) or no supplementation over 8 weeks | Reduced total and LDL cholesterol compared to baseline; no difference in total and LDL cholesterol between groups |

| Anti-inflammatory effect | ||||

| Kolehmainen et al. [70] | Randomized controlled trial | 27 volunteers with features of metabolic syndrome | 400 g/day fresh bilberries or habitual diet for 8 weeks | Reduced hsCRP, IL-6, IL-12, and LPS concentrations |

| Karlsen et al. [49] | Randomized controlled trial | 62 volunteers with increased risk of CVD | 330 mL/day bilberry juice (Corona Safteri, Rotvoll, Norway) or water for 4 weeks | Modulate NF-κB relatedinflammatory markers |

| Karlsen et al. [71] | Randomized controlled trial | 120 healthy volunteers | 300 mg/day Medox (with purified anthocyanins isolated from bilberries and blackcurrant), or placebo (maltodextrin) capsules for 3 weeks | Decreased NF-kB related pro-inflammatory chemokines, cytokines, and mediators of inflammatory responses |

| Zhu et al. [72] | Randomized placebo controlled, double-blinded trial | 150 hypercholesterolemia subjects | Anthocyanins (320 mg/d) purified from bilberry and blackcurrant, or placebo for 24 weeks | Decreased hsCRP, sVCAM-1, IL-1b and LDL cholesterol and increased HDL cholesterol |

| Freese et al. [73] | Randomized controlled trial | 96 healthy volunteers | Experimental diets either poor or rich in vegetables, berries and apple, and either richin linoleic acid or oleic acid for 6 weeks | No effect on platelet activation or inflammation markers |

| Hypoglycemic effect | ||||

| Hoggard et al. [87] | Randomized placebo controlled, double-blinded cross-over study | 8 volunteers with T2DM controlled by diet and lifestyle | 0.47 g bilberry extract (36% (w/w) anthocyanins) capsule or placebo | Decreased postprandial glycemia and insulin level |

| Qin et al. [88] | Randomized placebo controlled, double-blinded trial | 120 overweight dyslipidemic subjects | 160 mg anthocyanins twice daily or placebo for 12 weeks | No difference in glucose levels between groups |

| Effects on dyslipidemia | ||||

| Qin et al. [88] | Randomized placebo controlled, double-blinded trial | 120 overweight dyslipidemic subjects | 160 mg anthocyanins twice daily or placebo for 12 weeks | Decreased LDL cholesterol and increased HDL cholesterol and inhibited CETP |

| Erlund et al. [97] | Randomized, placebo controlled, single-blind, trial | 71 volunteers with at least one CV risk factor | 100 g whole bilberries and 50 g lingonberries one every other day, and blackcurrant or strawberry purée and cold-pressed chokeberry and raspberry juice on alternative day, or placebo (sugar water, sweet semolina porridge, sweet rice porridge and marmalade sweets) for 8 weeks | Reduced blood pressure, increased HDL cholesterol and prolonged PFA-100 CTs (CADP-CT) |

| Zhu et al. [98] | Randomized controlled, double-blinded trial | 150 hypercholesterolemic subjects | 320 mg/d anthocyanins purified from bilberry and blackcurrant, or placebo for 12 weeks | Increased FMD, cGMP, and HDL cholesterol, and decreased serum sVCAM-1 and LDL cholesterol |

| Zhu et al. [99] | Randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel study | 122 hypercholesterolemic subjects | 320 mg/d anthocyanins purified from bilberry and blackcurrant, or placebo for 24 weeks | Increased HDL cholesterol and decreased LDL cholesterol |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, S.W.; Tomlinson, B. Effects of Bilberry Supplementation on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Molecules 2020, 25, 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25071653

Chan SW, Tomlinson B. Effects of Bilberry Supplementation on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Molecules. 2020; 25(7):1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25071653

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Sze Wa, and Brian Tomlinson. 2020. "Effects of Bilberry Supplementation on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk" Molecules 25, no. 7: 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25071653

APA StyleChan, S. W., & Tomlinson, B. (2020). Effects of Bilberry Supplementation on Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Molecules, 25(7), 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25071653