Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Dipsacus asperoides Roots from Different Habitats in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

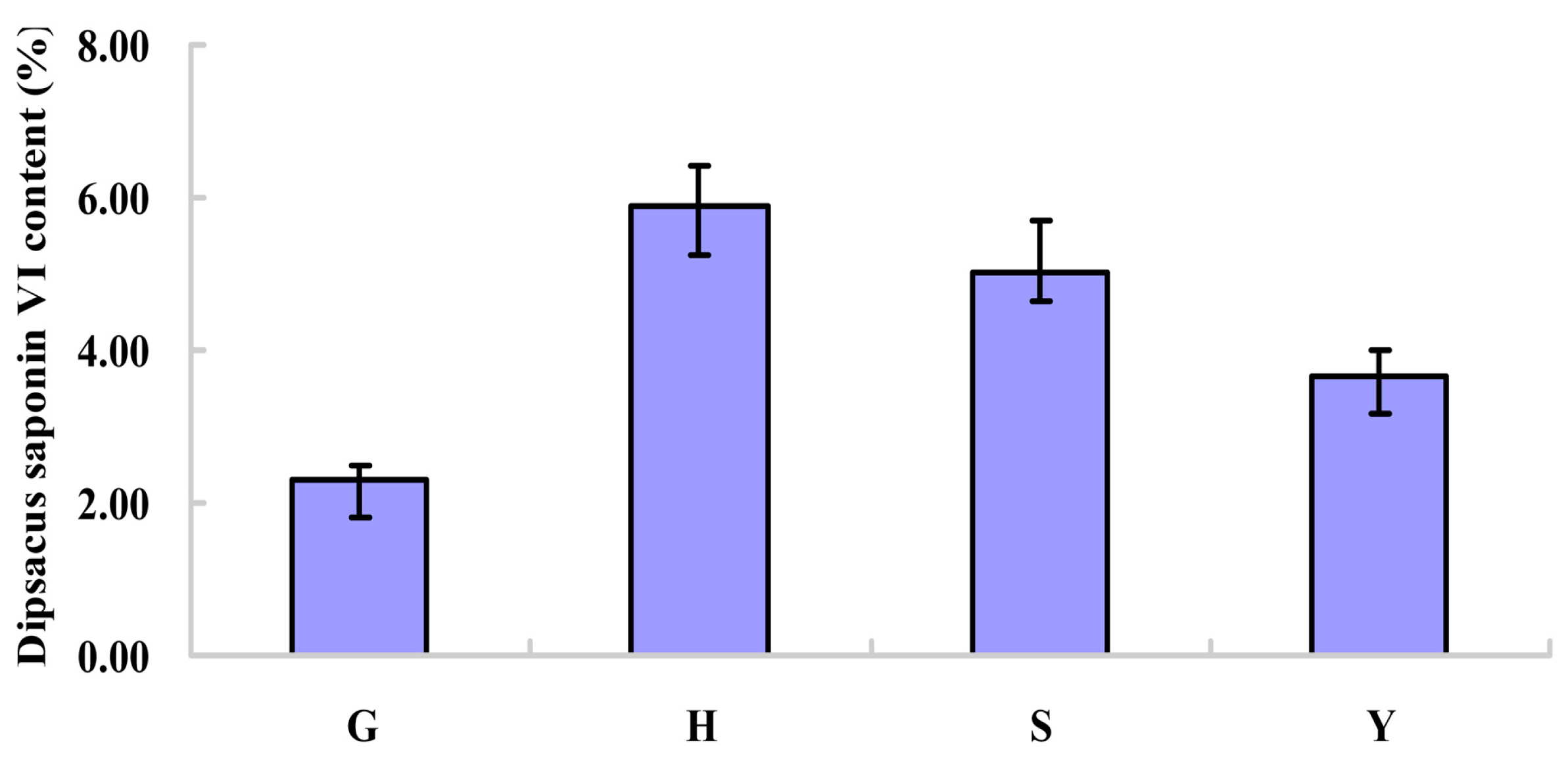

2.1. Content of Dipsacus Saponin VI from Different Habitats

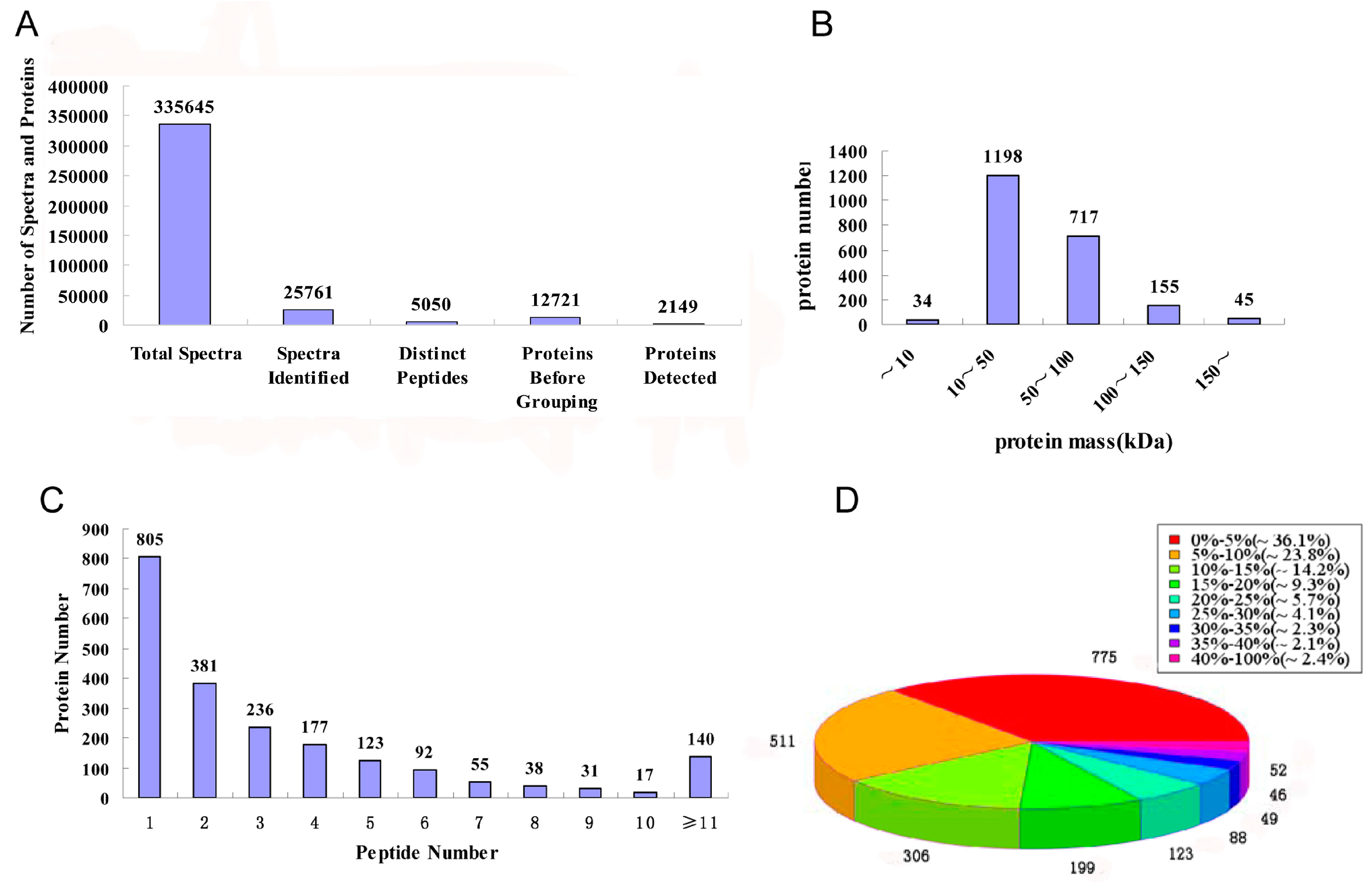

2.2. Protein Identification

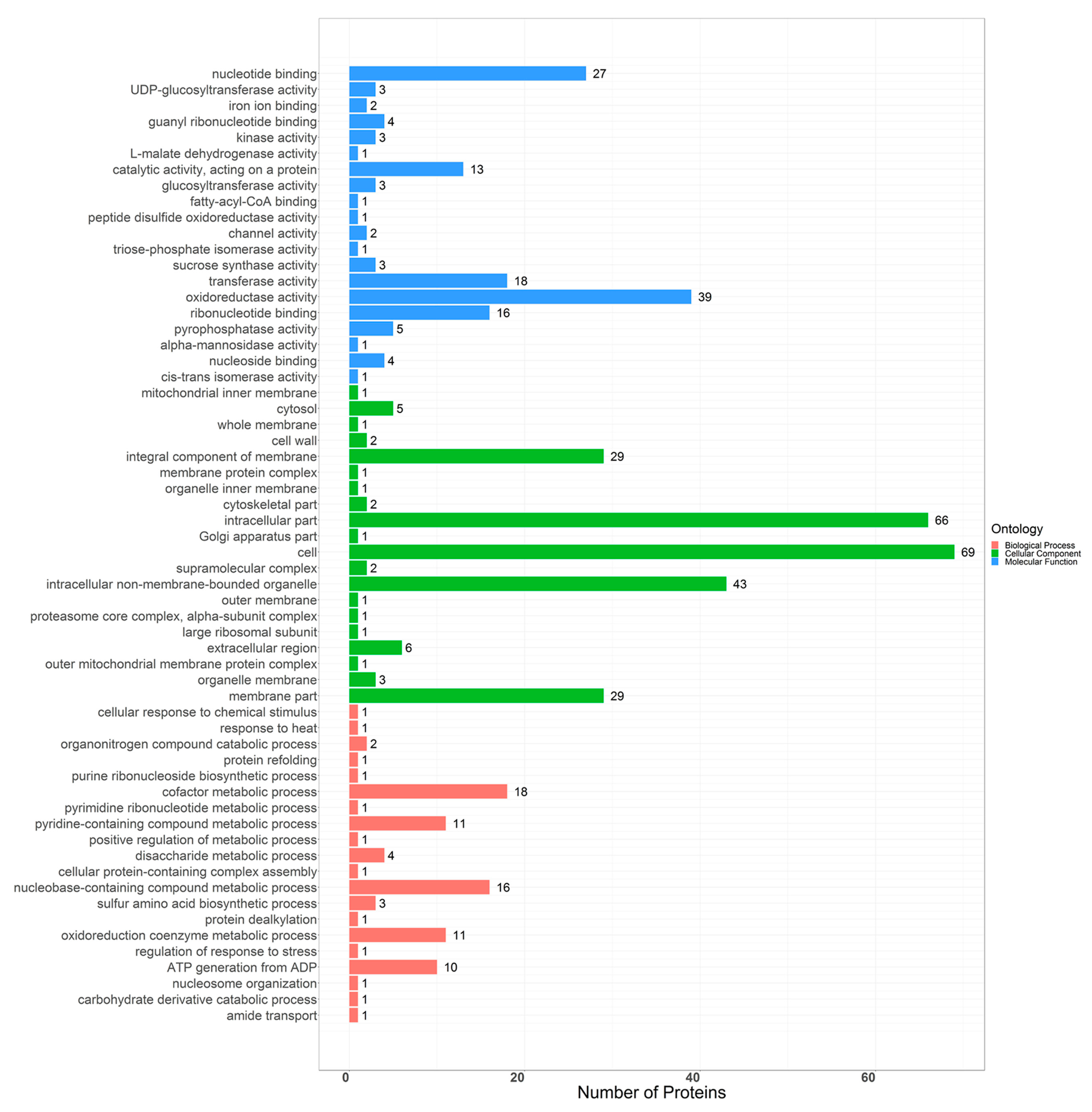

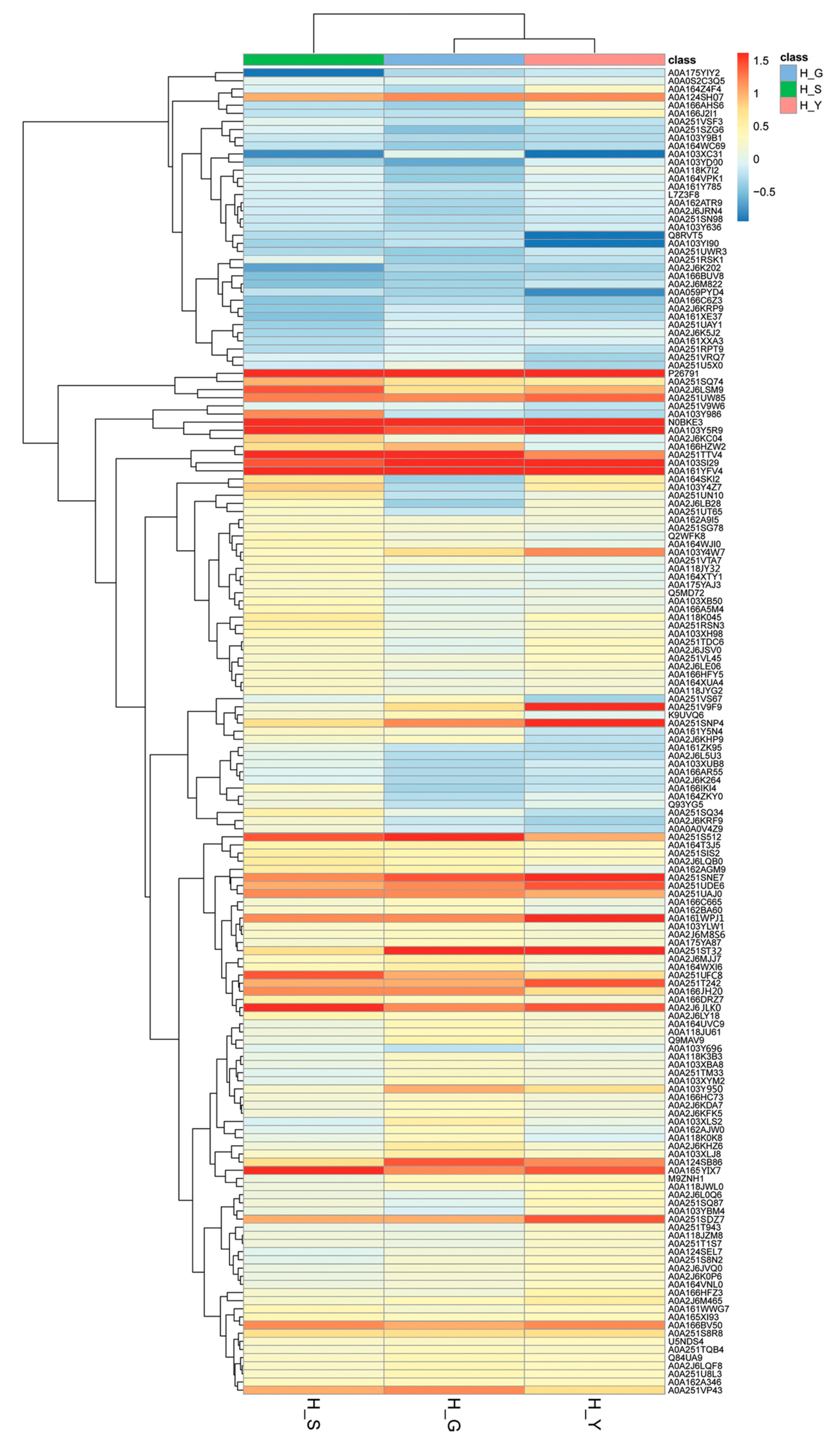

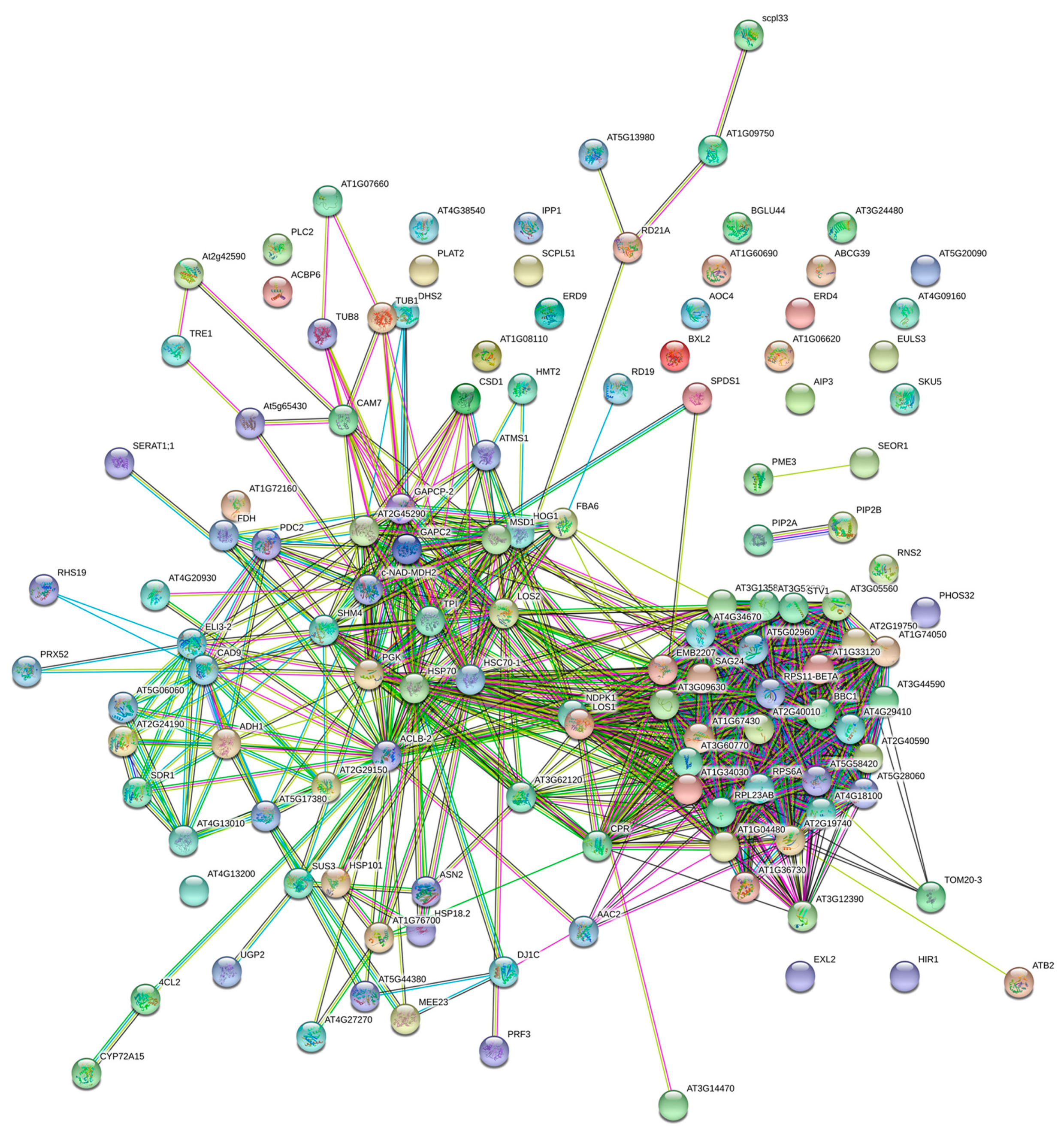

2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis of Differential Proteins

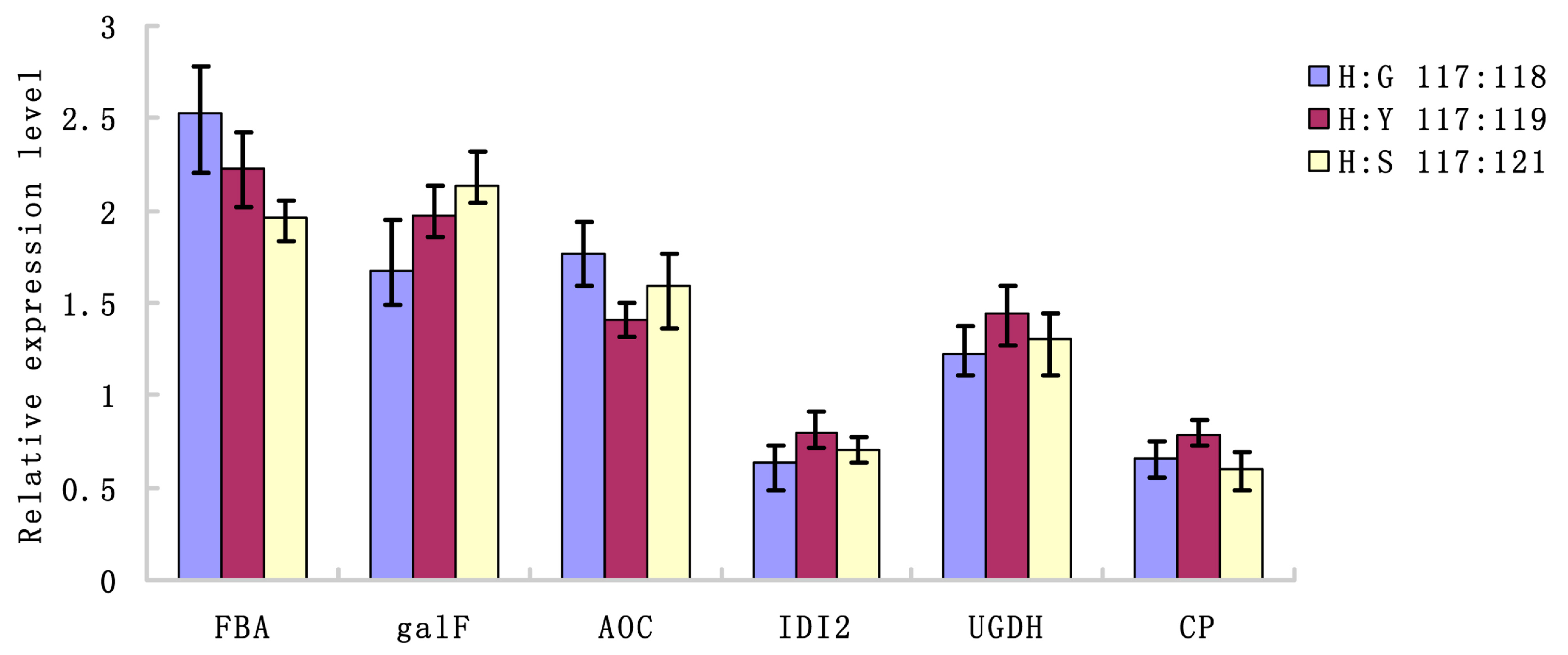

2.4. Verification of Transcriptional Expression of Candidate Genes for The Differential Expression of Proteins

3. Discussion

3.1. Energy and Carbohydrate Metabolism

3.2. Protein Metabolism

3.3. Stress and Defense

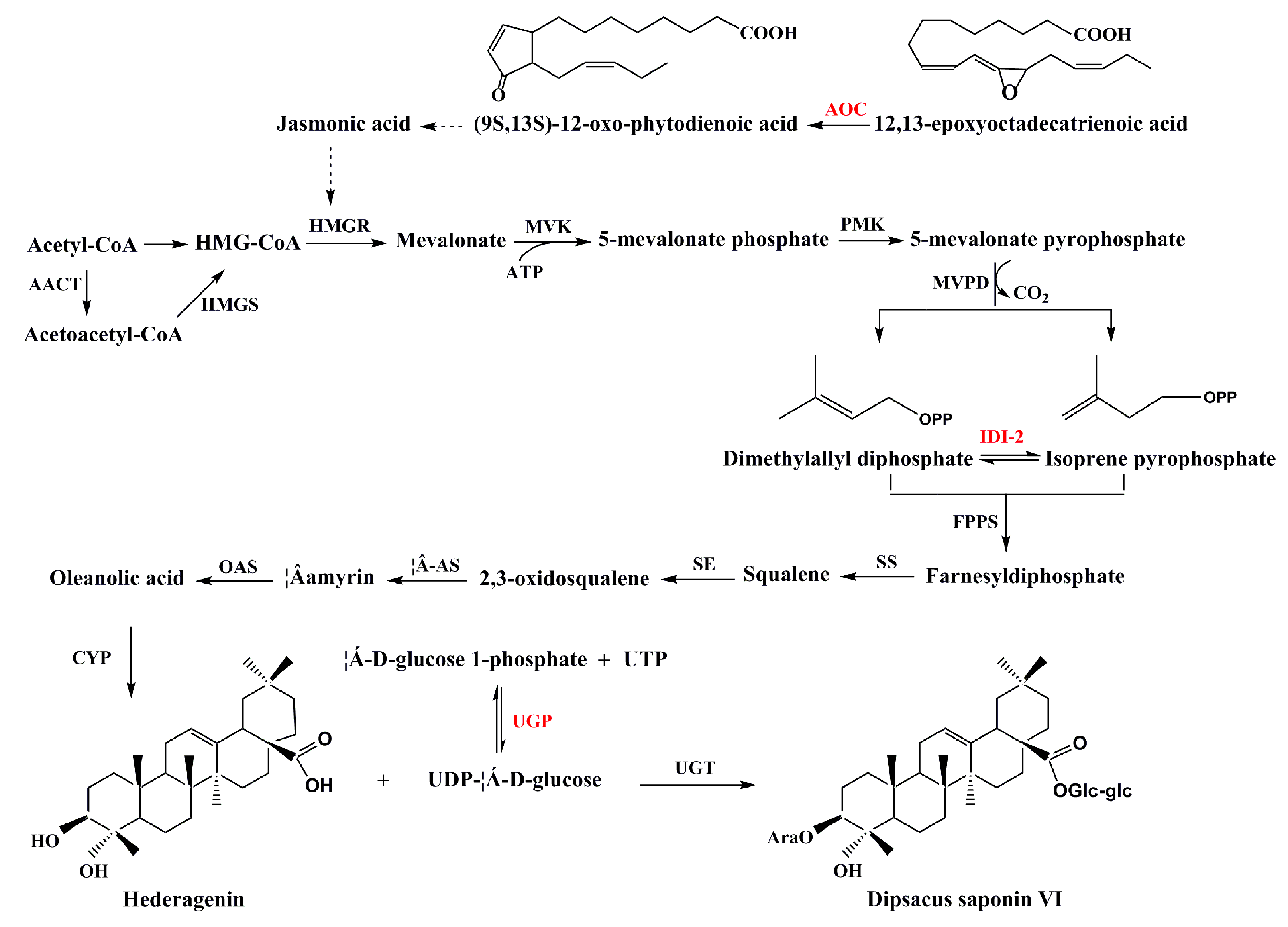

3.4. Secondary Metabolism

3.5. Nucleic Acid Metabolism

3.6. Amino Metabolism and Cell Wall Synthesis

3.7. Relationship Between Proteomic and Metabolomic Analysis in Different Habitats of D. asperoides

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Determination of Dipsacus Saponin VI

4.3. Protein Extraction, Digestion, and iTRAQ Labeling

4.4. Strong Cation Exchange

4.5. NanoLC–MS/MS Analysis by Q Exactive

4.6. Protein Identification

4.7. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.8. Quantitative PCR Detection

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.Y.; Liang, Y.L.; Hai, M.R.; Chen, J.W.; Gao, Z.J.; Hu, Q.Q.; Zhang, G.H.; Yang, S.C. Genome-wide transcriptional excavation of dipsacus asperoides unmasked both cryptic asperosaponin biosynthetic genes and SSR markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.F.; Yang, Z.L. Triterpene saponins from the roots of dipsacus asper and their protective effects against the Aβ25–35 induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, G.; Zhang, D.; Huang, W.; Ding, G.; Hu, H.; Tu, G.; Guo, B. New lignans and iridoid glycosides from dipsacus asper wall. Molecules 2015, 20, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Ma, B.; Guo, B. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of furofuran lignans, iridoid glycosides, and phenolic acids in radix dipsaci by UHPLC-Q-TOF/MS and UHPLC-PDA. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 154, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Liu, Q.Z.; Liu, Z.L. Chemical composition of dipsacus asper wallich ex candolle (Dipsacaceae) essential oil and its activity against mosquito larvae of aedes aegypti and culex pipiens pallens. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Kim, Y.G.; An, T.J.; Hur, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Cha, S.W.; Song, B.H. Variation of yield and loganin content according to harvesting stage of dipsacus asperoides wall. Korean J. Med. Crop. Sci. 2016, 24, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-H.; Yu, Z.-P.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Bao, J.; Zhu, K.-K.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, H. Triterpenoids and triterpenoid saponins from dipsacus asper and their cytotoxic and antibacterial activities. Phytochemistry 2019, 162, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Wang, X.L.; Guo, B.L.; Huang, W.H.; Xiao, P.G.; Huang, C.Q.; Zheng, L.Z.; Zhang, G.; Qin, L.; Tu, G.Z. Triterpenoid saponins from dipsacus asper and their activities in vitro. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 13, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, C.P. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; Part one; China Med Sci. Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.; Yan, G.X.; Yang, Q.; Zhai, L.N.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, F.Q.; Guan, R.Z. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis of brassica napus leaves reveals pathways associated with chlorophyll deficiency. J. Proteom. 2015, 113, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Wan, J.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, S.; Luo, G. iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis reveals the pathways for methanation of propionate facilitated by magnetite. Water Res. 2017, 108, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.A.; Zhang, K.; Islam, F.; Wang, J.; Athar, H.U.; Nawaz, A.; Ullah Zafar, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhou, W. Physiological and iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis of methyl jasmonate–induced tolerance in brassica napus under arsenic stress. Proteomics 2018, 18, 1700290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ríos, E.; Querol, A.; Guillamón, J.M. iTRAQ-based Proteome profiling of saccharomyces cerevisiae and cryotolerant species saccharomyces uvarum and saccharomyces kudriavzevii during low-temperature wine fermentation. J. Proteom. 2016, 146, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. Proteomics Analysis of Maize (Zea mays L.) grain based on iTRAQ reveals molecular mechanisms of poor grain filling in inferior grains. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Vidaña, D.I.; Rajwani, R.; Wong, M.S. The use of omic technologies applied to traditional Chinese medicine research. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 6359730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, S.S.; Kohler, A.; Yan, B.; Luo, H.M.; Chen, X.M.; Guo, S.X. iTRAQ and RNA-Seq analyses provide new insights into regulation mechanism of symbiotic germination of dendrobium officinale seeds (Orchidaceae). J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 2174–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zou, L.; Gu, W.; Hou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis of cultivated pseudostellaria heterophylla and its wild-type. J. Proteom. 2016, 139, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, Y.; Ling, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, S. Revealing proteins associated with symbiotic germination of gastrodia elata by proteomic analysis. Bot. Stud. 2018, 59, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.Y.; Guo, X.G.; Xie, L.P.; Xie, C.G.; Zhang, X.H.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Tang, Y.Y.; Pan, X.L.; Guo, A.G. Molecular Characterization, Gene Evolution, and Expression Analysis of The Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate Aldolase (FBA) Gene Family in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant. Sci. 2017, 8, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, T.; Gao, T.; Miao, Z.; Jiang, A.; Shi, L.; Ren, A.; Zhao, M. UDP-glucose Pyrophosphorylase Influences Polysaccharide Synthesis, Cell Wall Components, and Hyphal Branching in Ganoderma Lucidum via Regulation of The Balance between Glucose-1-phosphate and UDP-glucose. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 82, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Bertomeu, J.; Cascales-Miñana, B.; Irles-Segura, A.; Mateu, I.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Segura, J.; Ros, R. The Plastidial Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase Is Critical for Viable Pollen Development in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 2010, 152, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Deng, R.; Guo, Z.; Yang, S.; Deng, X. Genome-wide Identification and Characterization of Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase Genes Family in Wheat (Triticum aestivum). BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhtz, A.; Kolasa, A.; Arlt, K.; Walz, C.; Kehr, J. Xylem Sap Protein Composition is Conserved among Different Plant Species. Planta 2004, 219, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kabbage, M.; Liu, W.; Dickman, M.B. Aspartyl Protease-mediated Cleavage of BAG6 Is Necessary for Autophagy and Fungal Resistance in Plants. Plant. Cell 2016, 28, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasikumar, A.N.; Perez, W.B.; Kinzy, T.G. The Many Roles of The Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 1 Complex. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Rna 2012, 3, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhandono, S.; Apriyanto, A.; Ihsani, N. Isolation and Characterization of Three Cassava Elongation Factor 1 Alpha (MeEF1A) Promoters. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, R.; Nillegoda, N.B.; Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. The Hsp70 Chaperone Network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.A.; Nadella, V.; Clay, S.L.; Lindner, J.; Abrams, Z.; Wyatt, S.E. A Proteomics Approach Identifies Novel Proteins Involved in Gravitropic Signal Transduction. Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C. Molecular Cloning of Allene Oxide Cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 19132–19138. [Google Scholar]

- Antico, C.J.; Colon, C.; Banks, T.; Ramonell, K.M. Insights into The Role of Jasmonic Acid-mediated Defenses against Necrotrophic and Biotrophic Fungal Pathogens. Front. Biol. 2012, 7, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.W.; Gao, W.; Hahn, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Jasmonic Acid Improves Ginsenoside Accumulation in Adventitious Root Culture of Panax Ginseng CA Meyer. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 11, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.R.; Yuan, J.; Liu, L.H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Dai, C.C. Endophytic Pseudomonas Fluorescens Induced Sesquiterpenoid Accumulation Mediated by Gibberellic Acid and Jasmonic Acid in Atractylodes Macrocephala Koidz Plantlets. Plant. Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2019, 138, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, G.; Zhang, A.; Guo, Y.; Li, L.; Cui, L.; Luo, X.; Liu, C.; Xiao, J. Enhancing The Production of Tropane Alkaloids in Transgenic Anisodus Acutangulus Hairy Root Cultures by Over-expressing Tropinone Reductase I and Hyoscyamine-6β-hydroxylase. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 2883–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mairink, S.Z.; Barbosa, L.C.; Varejão, E.V.; Farias, E.S.; Santos, M.L.; Picanço, M.C. Larvicidal activity of synthetic tropane alkaloids against Ascia Monuste Orseis (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Pest. Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ruyck, J.; Janczak, M.W.; Neti, S.S.; Rothman, S.C.; Schubert, H.L.; Cornish, R.M.; Matagne, A.; Wouters, J.; Poulter, C.D. Determination of Kinetics and The Crystal Structure of A Novel Type 2 Isopentenyl Diphosphate: Dimethylallyl Diphosphate Isomerase from Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Chembiochem 2014, 15, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neti, S.S.; Eckert, D.M.; Poulter, C.D. Construction of Functional Monomeric Type 2 Isopentenyl Diphosphate: Dimethylallyl Diphosphate Isomerase. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 4229–4238. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Jin, J.; Hu, B.; Zeng, W.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, P. De Novo Characterization of Panax Japonicus CA Mey Transcriptome and Genes Related to Triterpenoid Saponin Biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 466, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G. Argonaute Proteins: Functional Insights and Emerging Roles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.F.; Wu, L.J.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.F.; Xie, D.X. Structural Evolution and Functional Diversification Analyses of Argonaute Protein. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 2576–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| Pathway | Number of Proteins | Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosome | 32 | map03010 |

| Carbon metabolism | 18 | map01200 |

| Biosynthesis of amino acids | 12 | map01230 |

| Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms | 10 | map00710 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 10 | map00500 |

| Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 9 | map00010 |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 9 | map00940 |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 6 | map00270 |

| MAPK signaling pathway-plant | 5 | map04016 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 4 | map00630 |

| Cyanoamino acid metabolism | 4 | map00460 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 4 | map00480 |

| Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | 3 | map04120 |

| Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 3 | map04141 |

| Plant-pathogen interaction | 3 | map04626 |

| Accession | Description | Score | Peptides | MW [kDa] | Calc. pI | 117:118 | 117:119 | 117:121 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy and Carbo hydrate Metabolism | ||||||||

| A0A161YFV4 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 287.2 | 10 | 38.3 | 6.77 | 2.244 | 1.905 | 1.791 |

| A0A103Y5R9 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | 278.14 | 8 | 52.8 | 7.17 | 1.468 | 1.926 | 2.029 |

| A0A251SNE7 | Tubulin beta chain | 58.38 | 8 | 50.5 | 4.86 | 1.428 | 1.9733 | 1.295 |

| N0BKE3 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 993.14 | 12 | 37 | 7.94 | 2.225 | 1.834 | 3.063 |

| A0A251UDE6 | Putative glycosyl hydrolase family protein | 23.63 | 2 | 75.5 | 8.78 | 1.354 | 1.467 | 1.286 |

| A0A251UAJ0 | Putative alcohol dehydrogenase superfamily, zinc-type | 93.15 | 4 | 38.7 | 6.65 | 1.336 | 1.263 | 1.365 |

| A0A161WPJ1 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 6.31 | 1 | 60.3 | 7.24 | 1.322 | 1.976 | 1.349 |

| A0A251S8R8 | Putative class II aaRS and biotin synthetases superfamily protein | 15.94 | 3 | 54.7 | 5.86 | 1.277 | 1.286 | 1.205 |

| A0A251V9F9 | Putative glyceraldehyde/Erythrose phosphate dehydrogenase family | 7.03 | 2 | 26.4 | 6 | 1.276 | 1.932 | 1.134 |

| A0A2J6M8S6 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | 13.9 | 2 | 40.6 | 5.6 | 1.248 | 1.247 | 1.147 |

| A0A103YI90 | AAA+ ATPase domain-containing protein | 109.03 | 5 | 163.7 | 6.49 | 0.735 | 0.924 | 0.840 |

| A0A251UWR3 | Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier | 16.51 | 1 | 5.9 | 8.22 | 0.756 | 0.885 | 0.816 |

| Protein Metabolism | ||||||||

| A0A251TTV4 | Putative eukaryotic aspartyl protease family protein | 42.48 | 2 | 48.4 | 7.49 | 2.0198 | 1.344 | 1.627 |

| P26791 | Heat shock protein 70 | 215.19 | 10 | 72 | 5.25 | 2.013 | 1.817 | 1.710 |

| A0A251ST32 | Putative heat shock protein 81-2 | 310.6 | 19 | 79.9 | 5.03 | 1.618 | 1.882 | 1.206 |

| A0A251S512 | 40S ribosomal protein S24 | 19.77 | 2 | 14.1 | 10.54 | 1.615 | 1.297 | 1.462 |

| A0A124SB86 | 60S ribosomal protein L13 | 21.85 | 4 | 23.6 | 11.17 | 1.465 | 1.390 | 1.209 |

| A0A2J6JLK0 | Elongation factor 1-alpha | 405.87 | 14 | 49.3 | 9.07 | 1.338 | 1.417 | 1.657 |

| A0A166JH20 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 2.28 | 2 | 18.7 | 7.81 | 1.315 | 1.221 | 1.344 |

| A0A165YIX7 | Proteasome subunit alpha type | 32.64 | 2 | 27.4 | 6.3 | 1.312 | 1.424 | 1.989 |

| A0A251VP43 | Putative nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha-like protein 3 | 78.95 | 3 | 21.9 | 4.55 | 1.3008 | 1.218 | 1.288 |

| A0A124SH07 | Chaperonin 21, chloroplast | 1.82 | 1 | 26.4 | 8.05 | 1.3045 | 1.364 | 1.278 |

| A0A251T242 | Argonaute/Dicer protein | 23.03 | 3 | 17.3 | 10.29 | 1.283 | 1.441 | 1.285 |

| A0A166BV50 | 40S ribosomal protein S6 | 15.74 | 4 | 28.2 | 10.67 | 1.241 | 1.340 | 1.333 |

| A0A251V9W6 | Putative 14-3-3 domain-containing protein | 60.62 | 5 | 29.3 | 4.83 | 0.6296 | 0.753 | 0.502 |

| A0A161Y785 | Carboxypeptidase | 11.44 | 2 | 50.2 | 7.37 | 0.7179 | 0.668 | 0.535 |

| A0A103YD00 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme/RWD-like protein | 2.69 | 1 | 19.4 | 7.88 | 0.758 | 0.601 | 0.779 |

| A0A118JY32 | Protein transport protein Sec61 subunit beta | 3.8 | 1 | 8.5 | 10.96 | 0.785 | 0.508 | 0.746 |

| Amino Metabolism | ||||||||

| A0A251SNP4 | Putative 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate homocysteine methyltransferase | 707.58 | 14 | 92.5 | 6.76 | 1.309 | 1.944 | 1.220 |

| A0A0S2C3Q5 | Phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase | 27.93 | 2 | 25.6 | 6.9 | 0.6488 | 0.614 | 0.572 |

| Stress and Defense | ||||||||

| A0A103SI29 | Allene oxide cyclase | 9.34 | 1 | 17.1 | 9.54 | 1.8996 | 1.377 | 1.465 |

| A0A251UFC8 | Phosphoinositide phospholipase C | 9.63 | 2 | 20.2 | 5.72 | 1.2614 | 1.2095 | 1.431 |

| A0A103Y696 | Peroxidase | 6.64 | 1 | 34.2 | 7.83 | 0.702 | 0.456 | 0.573 |

| A0A251VSF3 | Putative berberine/berberine-like, FAD-binding, type 2 | 23.91 | 3 | 61 | 4.97 | 0.714 | 0.703 | 0.518 |

| Q8RVT5 | Acyl-CoA-binding protein | 15.33 | 1 | 9.9 | 5.5 | 0.777 | 0.977 | 0.834 |

| Q93YG5 | Superoxide dismutase (Fragment) | 8.53 | 2 | 15.9 | 6.27 | 0.794 | 0.602 | 0.546 |

| Nucleic Acid Metabolism | ||||||||

| A0A103Y950 | Argonaute/Dicer protein | 37.43 | 7 | 120.9 | 9.39 | 1.2796 | 1.230 | 1.062 |

| A0A251SDZ7 | Putative DNA/RNA-binding protein Alba-like protein | 5.63 | 1 | 25.2 | 10.24 | 1.255 | 1.444 | 1.267 |

| Cell Wall Synthesis | ||||||||

| A0A103Y4W7 | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | 51.35 | 6 | 53.1 | 5.85 | 1.224 | 1.399 | 1.138 |

| A0A103XC31 | Glucose/ribitol dehydrogenase | 3.42 | 1 | 34.3 | 6.8 | 0.607 | 0.975 | 0.890 |

| Secondary Metabolism | ||||||||

| A0A251RSK1 | Putative tropinone reductase 1 | 20.44 | 2 | 31.8 | 0.709 | 0.767 | 0.713 | 0.671 |

| A0A059PYD4 | Isopentyl diphosphate isomerase 2 | 26.67 | 4 | 32.5 | 5.31 | 0.782 | 0.880 | 0.720 |

| Gene | Protein | Forward/Reverse Primer Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| FBA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | Forward primer AGTACTGCTGCTGGAAAACCT Reverse primer CATCGGTACCAGCAAGCTCA |

| galF | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | Forward primer GGCTGCTGCTGATACCGA Reverse primer GCATCCCATTGTTGTCCC |

| AOC | Allene oxide cyclase | Forward primer TCTATGTTATCTACGGAATGG Reverse primer AACCGAAAGGTAGGCATC |

| IDI2 | Isopentyl diphosphate isomerase 2 | Forward primer TCTATGTTATCTACGGAATGG Reverse primer GAGAAAGACGAGCGAGGT |

| UGDH | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | Forward primer ACATCATCACGACCAATCT Reverse primer GTCCTTACCAACGGCATA |

| CP | Carboxypeptidase | Forward primer CTAAAGTGGGAAGGCATAA Reverse primer TACAGGGCTGATCTACGG |

| 18sRNA | Forward primer AGCAGATTGACCAGCGAACA Reverse primer CAGAAAGGAGCACCACCC |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Dipsacus asperoides Roots from Different Habitats in China. Molecules 2020, 25, 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163605

Jin H, Yu H, Wang H, Zhang J. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Dipsacus asperoides Roots from Different Habitats in China. Molecules. 2020; 25(16):3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163605

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Haijun, Hua Yu, Haixia Wang, and Jia Zhang. 2020. "Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Dipsacus asperoides Roots from Different Habitats in China" Molecules 25, no. 16: 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163605

APA StyleJin, H., Yu, H., Wang, H., & Zhang, J. (2020). Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Dipsacus asperoides Roots from Different Habitats in China. Molecules, 25(16), 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163605