Current Aspects of siRNA Bioconjugate for In Vitro and In Vivo Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The siRNA Conjugation Strategy

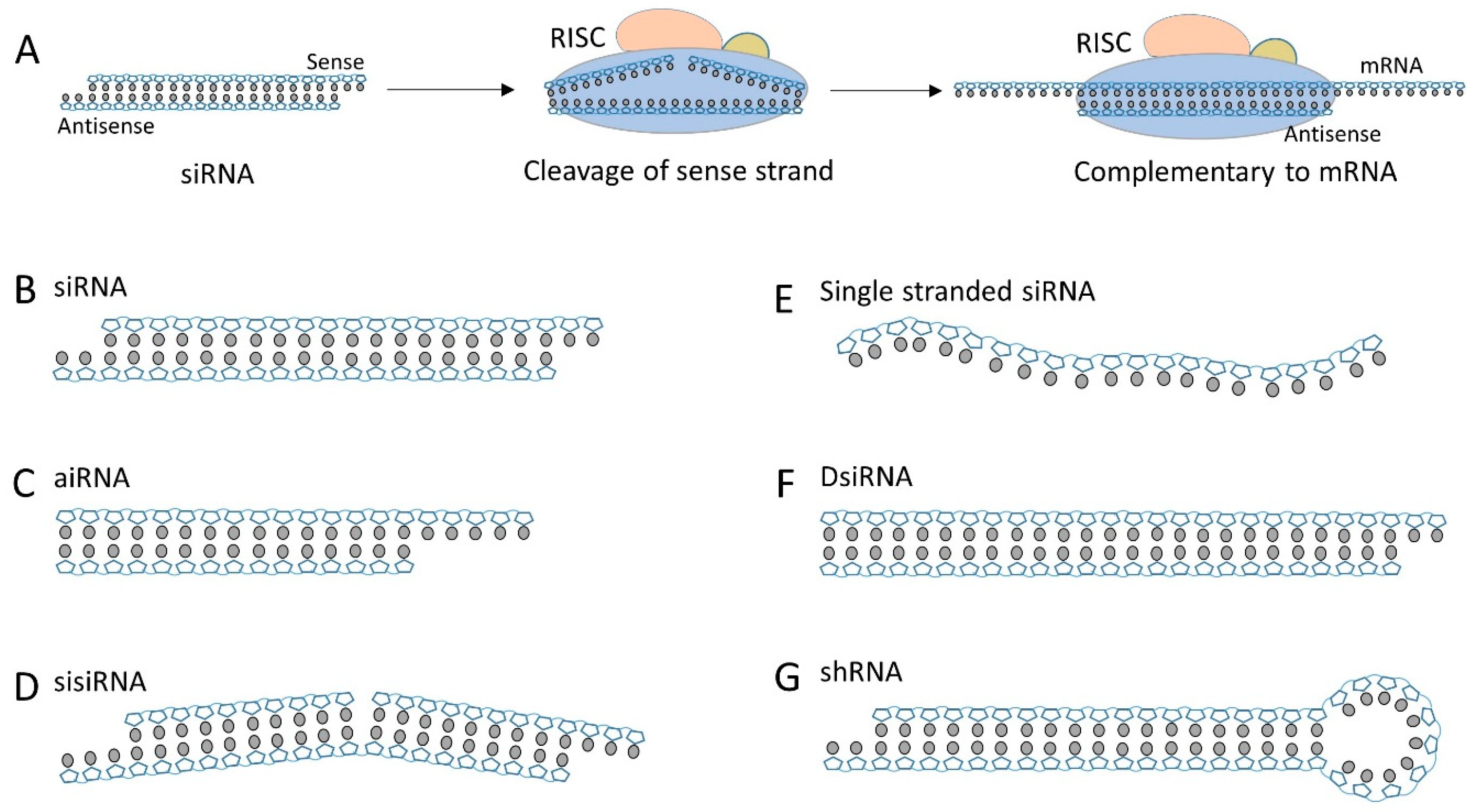

2.1. Structural Diversity of the siRNA Duplex

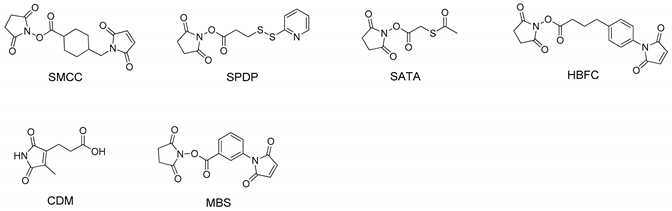

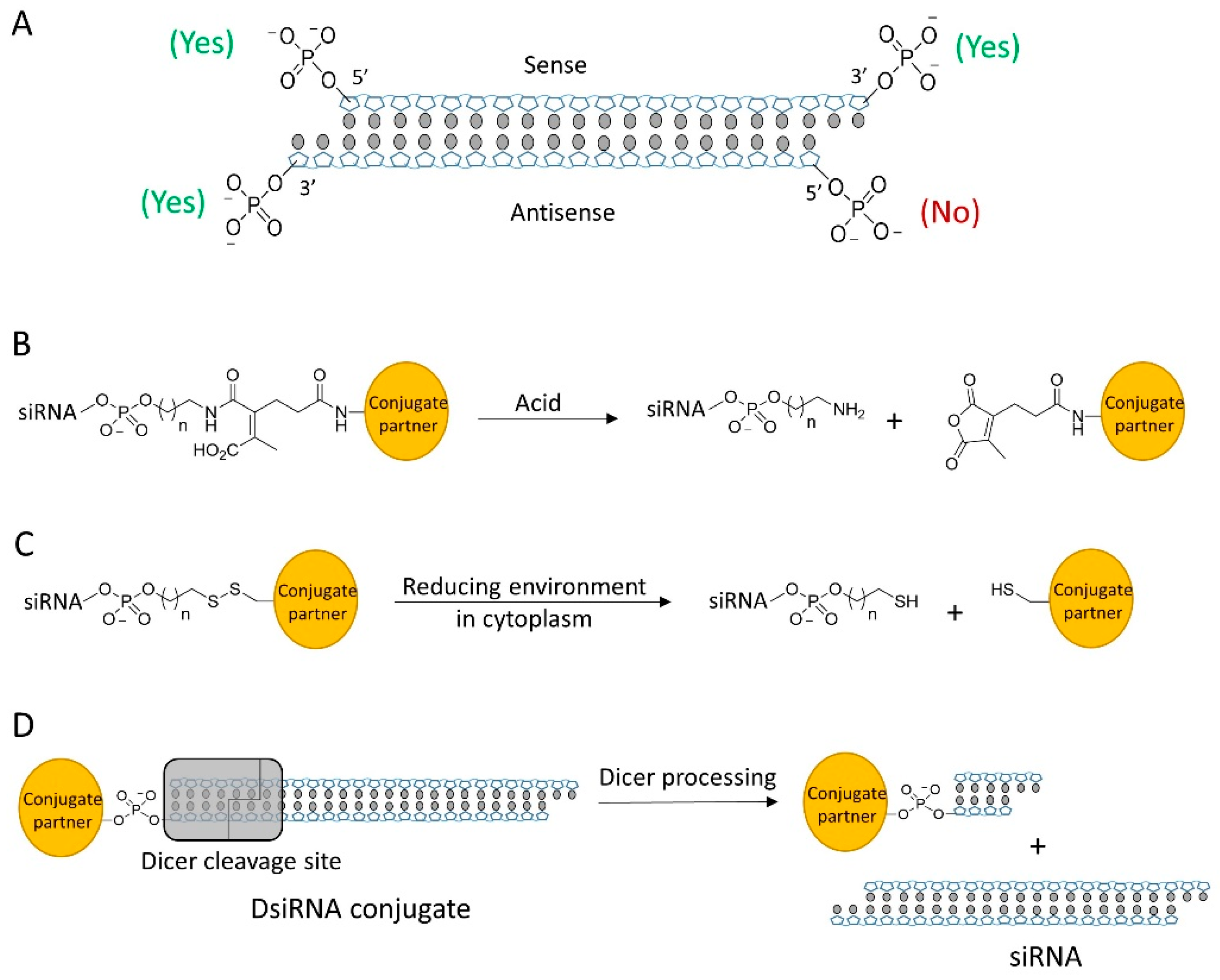

2.2. Conjugation Sites and Linkers

3. siRNA Conjugated with Ligand for Targeted Delivery

3.1. siRNA Conjugated with Immunoprotein

3.2. siRNA Conjugated with Peptide Ligand

3.3. siRNA-Aptamer Bioconjugate

3.4. Small Molecules as Ligand for siRNA Conjugation

4. Lipid–siRNA Conjugate

4.1. Cholesterol siRNA Conjugate

4.2. Bioconjugation with Other Lipids

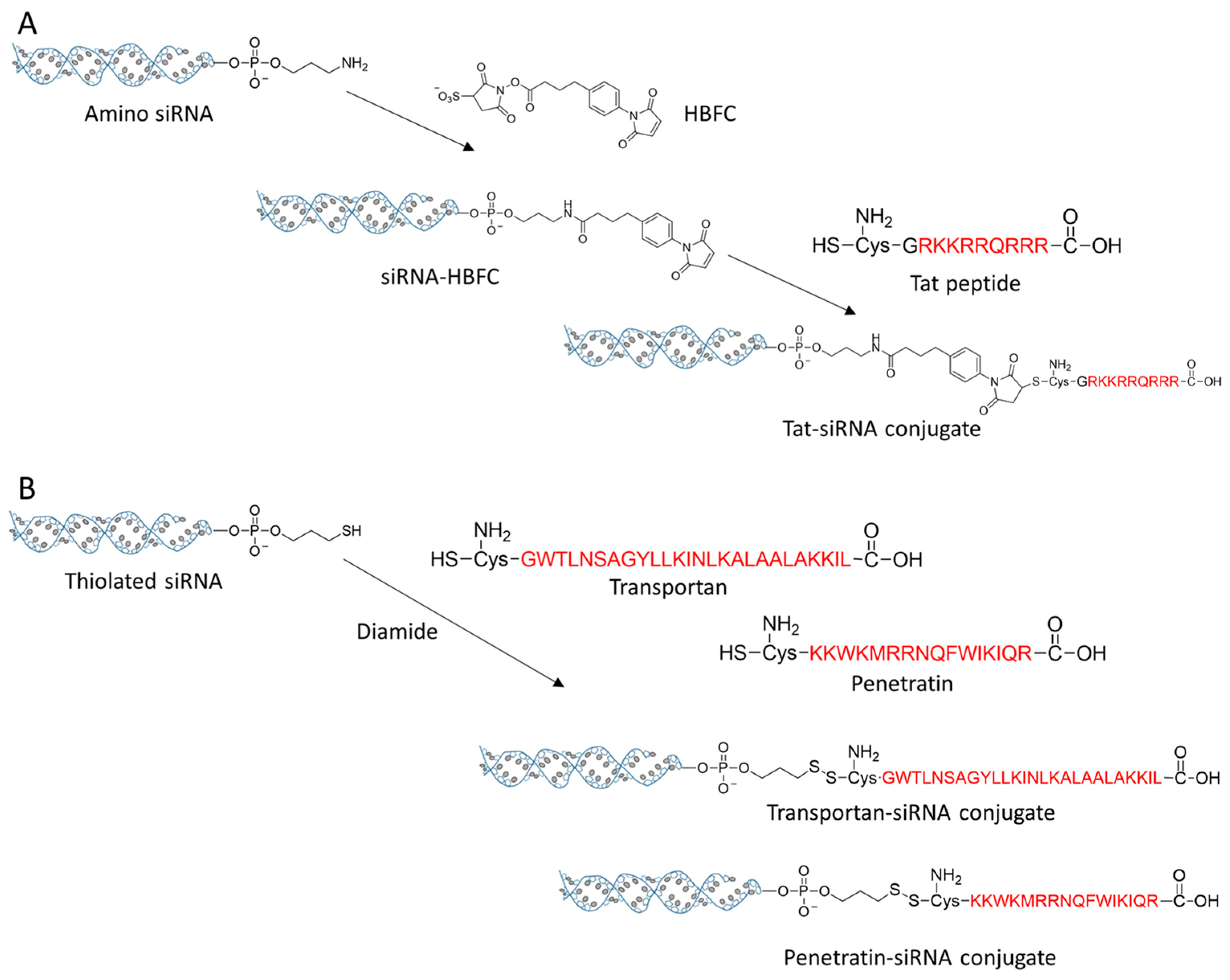

5. siRNA Conjugated with Cell-Penetrating Peptides

5.1. Conjugate with Cationic CPP

5.2. Conjugate with Activatable CPP

6. siRNA Conjugated with Polymer

6.1. Polymer–siRNA Conjugate

6.2. Dynamic Polyconjugate of siRNA

7. siRNA Conjugated with Nanoparticles

7.1. Spherical siRNA Nanoparticle

7.2. siRNA Conjugated with Other Nanoparticles

8. Future Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| nt | Nucleotide |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| CPP | Cell-penetrating Peptide |

| RISC | RNA-Induced Silencing Complex |

| aiRNA | Asymmetric interfering RNA |

| DsiRNA | Dicer-substrate siRNA |

| sisiRNA | Small internally segmented interfering RNA |

| ARC | Antibody siRNA Conjugate |

| IGF1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 |

| HUVEC | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen |

| ASGRP | Asialoglycoprotein receptor |

| GalNAc | N-acetylgalactosamine |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low Density Lipoprotein |

| SR-BI | Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 1 |

| CDM | Carboxylated Dimethyl Maleic acid |

| NAG | N-Acetyl-d-Glucosamine |

| LCA | Lithocholic Acid |

| DCA | Docosanoic Acid |

| PC-DCA | Phosphocholine-DCA |

| HBFC | sulfosuccinimidyl 4-(p-maleimidophenyl)butyrate |

| MBS | m-MaleimidoBenzoyl N-hydroxySuccinimide |

| SPDP | Succinimidyl 3-(2-PyridylDithio)Propionate |

| CDK9 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 9 |

| MMP2 | Matrix MetalloPeptidase 2 |

| LCST | Lower Critical Solution Temperature |

| SNA | Spherical Nucleic Acid |

| MN | Magnetic Nanoparticle |

| QD | Quantum Dot |

References

- Lares, M.R.; Rossi, J.J.; Ouellet, D.L. RNAi and small interfering RNAs in human disease therapeutic applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, K.A.; Langer, R.; Anderson, D.G. Knocking down barriers: Advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedmi, R.; Veiga, N.; Ramishetti, S.; Goldsmith, M.; Rosenblum, D.; Dammes, N.; Hazan-Halevy, I.; Nahary, L.; Leviatan-Ben-Arye, S.; Harlev, M.; et al. A modular platform for targeted RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristen, A.V.; Ajroud-Driss, S.; Conceicao, I.; Gorevic, P.; Kyriakides, T.; Obici, L. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2019, 9, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenny, K.W.; Lam, A.J.W. What is the Future of SiRNA Therapeutics. J. Drug Des. Res. 2014, 1, 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, M.-F.; Chan, H.; Given, B.; Hamilton, J.; Schluep, T.; Lewis, D.; Lai, C.-L.; Locarnini, S.; Lau, J.; Gish, R. Phase II, dose ranging study of ARC-520, a siRNA-based therapeutic, in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: lb-21. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1280A. [Google Scholar]

- Schluep, T.; Lickliter, J.; Hamilton, J.; Lewis, D.L.; Lai, C.L.; Lau, J.Y.; Locarnini, S.A.; Gish, R.G.; Given, B.D. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of ARC-520 Injection, an RNA Interference-Based Therapeutic for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection, in Healthy Volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2017, 6, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, T.S.; Karsten, V.; Chan, A.; Chiesa, J.; Boyce, M.; Bettencourt, B.R.; Hutabarat, R.; Nochur, S.; Vaishnaw, A.; Gollob, J. Clinical Proof of Concept for a Novel Hepatocyte-Targeting GalNAc-siRNA Conjugate. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, M.; Messere, A. Recent progress in chemically modified siRNAs. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Dasaradhi, P.V.; Mohmmed, A.; Malhotra, P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.K. RNA interference: Biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 657–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.L.; Bartz, S.R.; Schelter, J.; Kobayashi, S.V.; Burchard, J.; Mao, M.; Li, B.; Cavet, G.; Linsley, P.S. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.L.; Burchard, J.; Schelter, J.; Chau, B.N.; Cleary, M.; Lim, L.; Linsley, P.S. Widespread siRNA “off-target” transcript silencing mediated by seed region sequence complementarity. RNA 2006, 12, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Rogoff, H.A.; Li, C.J. Asymmetric RNA duplexes mediate RNA interference in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.Y.; Rana, T.M. Potent RNAi by short RNA triggers. RNA 2008, 14, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramsen, J.B.; Laursen, M.B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Lena, S.W.; Babu, B.R.; Wengel, J.; Kjems, J. Improved silencing properties using small internally segmented interfering RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 5886–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, W.F.; Prakash, T.P.; Murray, H.M.; Kinberger, G.A.; Li, W.; Chappell, A.E.; Li, C.S.; Murray, S.F.; Gaus, H.; Seth, P.P.; et al. Single-stranded siRNAs activate RNAi in animals. Cell 2012, 150, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Behlke, M.A.; Rose, S.D.; Chang, M.S.; Choi, S.; Rossi, J.J. Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snead, N.M.; Wu, X.; Li, A.; Cui, Q.; Sakurai, K.; Burnett, J.C.; Rossi, J.J. Molecular basis for improved gene silencing by Dicer substrate interfering RNA compared with other siRNA variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 6209–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.B.; Guthrie, E.H.; Huang, M.T.; Taxman, D.J. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA): Design, delivery, and assessment of gene knockdown. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 629, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, D.D.; Vorhies, J.S.; Senzer, N.; Nemunaitis, J. siRNA vs. shRNA: Similarities and differences. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.L.; Rana, T.M. siRNA function in RNAi: A chemical modification analysis. RNA 2003, 9, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khvorova, A.; Reynolds, A.; Jayasena, S.D. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 2003, 115, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.S.; Hutvagner, G.; Du, T.; Xu, Z.; Aronin, N.; Zamore, P.D. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell 2003, 115, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorova, A.; Watts, J.K. The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J.O., II; Andrechek, E.R.; Wang, Y.; Viles, K.D.; Rempel, R.E.; Gilboa, E.; Sullenger, B.A.; Giangrande, P.H. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Hatori, Y.; Akagi, R.; Mihara, K.; Yanagihara, K.; Seyama, T. Antitumor effect of palmitic acid-conjugated DsiRNA for colon cancer in a mouse subcutaneous tumor model. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2019, 93, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.J.; Brown, C.R.; Shaikh, S.; Trapp, C.; Schlegel, M.K.; Qian, K.; Sehgal, A.; Rajeev, K.G.; Jadhav, V.; Manoharan, M.; et al. Advanced siRNA Designs Further Improve In Vivo Performance of GalNAc-siRNA Conjugates. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czauderna, F.; Fechtner, M.; Dames, S.; Aygun, H.; Klippel, A.; Pronk, G.J.; Giese, K.; Kaufmann, J. Structural variations and stabilising modifications of synthetic siRNAs in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 2705–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerson, C.R.; Sioufi, N.; Jarres, R.; Prakash, T.P.; Naik, N.; Berdeja, A.; Wanders, L.; Griffey, R.H.; Swayze, E.E.; Bhat, B. Fully 2′-modified oligonucleotide duplexes with improved in vitro potency and stability compared to unmodified small interfering RNA. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumer, S.; Baumer, N.; Appel, N.; Terheyden, L.; Fremerey, J.; Schelhaas, S.; Wardelmann, E.; Buchholz, F.; Berdel, W.E.; Muller-Tidow, C. Antibody-mediated delivery of anti-KRAS-siRNA in vivo overcomes therapy resistance in colon cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Zhu, P.; Lee, S.K.; Chowdhury, D.; Kussman, S.; Dykxhoorn, D.M.; Feng, Y.; Palliser, D.; Weiner, D.B.; Shankar, P.; et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Ban, H.S.; Kim, S.S.; Wu, H.; Pearson, T.; Greiner, D.L.; Laouar, A.; Yao, J.; Haridas, V.; Habiro, K.; et al. T cell-specific siRNA delivery suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Cell 2008, 134, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblett, K.J.; Senter, P.D.; Chace, D.F.; Sun, M.M.; Lenox, J.; Cerveny, C.G.; Kissler, K.M.; Bernhardt, S.X.; Kopcha, A.K.; Zabinski, R.F.; et al. Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 7063–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuellar, T.L.; Barnes, D.; Nelson, C.; Tanguay, J.; Yu, S.F.; Wen, X.; Scales, S.J.; Gesch, J.; Davis, D.; van Brabant Smith, A.; et al. Systematic evaluation of antibody-mediated siRNA delivery using an industrial platform of THIOMAB-siRNA conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 1189–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugo, T.; Terada, M.; Oikawa, T.; Miyata, K.; Nishimura, S.; Kenjo, E.; Ogasawara-Shimizu, M.; Makita, Y.; Imaichi, S.; Murata, S.; et al. Development of antibody-siRNA conjugate targeted to cardiac and skeletal muscles. J. Control. Release 2016, 237, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Mahato, R.; Cheng, K. The role of HER2 in cancer therapy and targeted drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2010, 146, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, J.J.; Kelly, T.S.; Andrews, R.; Rogers, B.E. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 64Cu-labeled DOTA-linker-bombesin(7-14) analogues containing different amino acid linker moieties. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Shukla, R.S.; Qin, B.; Li, B.; Cheng, K. Development of a peptide-drug conjugate for prostate cancer therapy. Mol Pharm 2011, 8, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Gao, X. Functional peptides for siRNA delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 110–111, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarone, G.; Edupuganti, O.P.; Chen, C.P.; Wickstrom, E. Insulin receptor substrate 1 knockdown in human MCF7 ER+ breast cancer cells by nuclease-resistant IRS1 siRNA conjugated to a disulfide-bridged D-peptide analogue of insulin-like growth factor 1. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Samarsky, D.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, G.; Wu, P.; Zuo, X.; Deng, H.; et al. Tumor-targeted in vivo gene silencing via systemic delivery of cRGD-conjugated siRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 11805–11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, B.; Wei, Y.; Huang, W.; Teng, M.; He, S.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; He, G.; Bai, X.; Liu, X.; et al. An Efficient Bivalent Cyclic RGD-PIK3CB siRNA Conjugate for Specific Targeted Therapy against Glioblastoma In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.R.; Ming, X.; Fisher, M.; Lackey, J.G.; Rajeev, K.G.; Manoharan, M.; Juliano, R.L. Multivalent cyclic RGD conjugates for targeted delivery of small interfering RNA. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011, 22, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandioso, A.; Massaguer, A.; Villegas, N.; Salvans, C.; Sanchez, D.; Brun-Heath, I.; Marchan, V.; Orozco, M.; Terrazas, M. Efficient siRNA-peptide conjugation for specific targeted delivery into tumor cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2017, 53, 2870–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, K.; Akao, Y.; Furuichi, Y.; Ueno, Y. Enhanced Intercellular Delivery of cRGD-siRNA Conjugates by an Additional Oligospermine Modification. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8226–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, T.G. LHRH receptor-mediated delivery of siRNA using polyelectrolyte complex micelles self-assembled from siRNA-PEG-LHRH conjugate and PEI. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008, 19, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Guan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. Reductive nanocomplex encapsulation of cRGD-siRNA conjugates for enhanced targeting to cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 7255–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Aptamer-targeted cell-specific RNA interference. Silence 2010, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, L.A.; Trifonova, R.; Vrbanac, V.; Basar, E.; McKernan, S.; Xu, Z.; Seung, E.; Deruaz, M.; Dudek, T.; Einarsson, J.I.; et al. Inhibition of HIV transmission in human cervicovaginal explants and humanized mice using CD4 aptamer-siRNA chimeras. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ribas, J.; Chowdhury, W.H.; Castanares, M.; Zhang, Z.; Laiho, M.; DeWeese, T.L.; Lupold, S.E. Prostate-targeted radiosensitization via aptamer-shRNA chimeras in human tumor xenografts. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.F.; Tur, M.K.; Barth, S. An aptamer-siRNA chimera silences the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 gene and induces apoptosis in cancers expressing alphavbeta3 integrin. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013, 23, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zaia, J.; Rossi, J.J. Novel dual inhibitory function aptamer-siRNA delivery system for HIV-1 therapy. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortylewski, M.; Swiderski, P.; Herrmann, A.; Wang, L.; Kowolik, C.; Kujawski, M.; Lee, H.; Scuto, A.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; et al. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hossain, D.M.; Nechaev, S.; Kozlowska, A.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Kowolik, C.M.; Swiderski, P.; Rossi, J.J.; Forman, S.; et al. TLR9-mediated siRNA delivery for targeting of normal and malignant human hematopoietic cells in vivo. Blood 2013, 121, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, F.; Kolonias, D.; McNamara, J.O., II; Gilboa, E. Targeting 4-1BB costimulation to disseminated tumor lesions with bi-specific oligonucleotide aptamers. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassie, J.P.; Liu, X.Y.; Thomas, G.S.; Whitaker, R.M.; Thiel, K.W.; Stockdale, K.R.; Meyerholz, D.K.; McCaffrey, A.P.; McNamara, J.O., II; Giangrande, P.H. Systemic administration of optimized aptamer-siRNA chimeras promotes regression of PSMA-expressing tumors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyacioglu, O.; Stuart, C.H.; Kulik, G.; Gmeiner, W.H. Dimeric DNA Aptamer Complexes for High-capacity-targeted Drug Delivery Using pH-sensitive Covalent Linkages. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Cinier, M.; Fox, S.R.; Ben-Johnathan, N.; Guo, P. Assembly of therapeutic pRNA-siRNA nanoparticles using bipartite approach. Mol Ther 2011, 19, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Meng, L.; Ye, M.; Yang, L.; Sefah, K.; O’Donoghue, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, X.; Huang, J.; Song, E.; et al. Self-assembled aptamer-based drug carriers for bispecific cytotoxicity to cancer cells. Chem. Asian J. 2012, 7, 1630–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Kularatne, S.A.; Qi, L.; Kleindl, P.; Leamon, C.P.; Hansen, M.J.; Low, P.S. Ligand-targeted delivery of small interfering RNAs to malignant cells and tissues. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2009, 1175, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, C.; Frohlich, T.; Lachelt, U.; Rohl, I.; Vornlocher, H.P.; Hadwiger, P.; Wagner, E. Defined Folate-PEG-siRNA Conjugates for Receptor-specific Gene Silencing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, W.; Gao, X. Synthetic Polymer Tag for Intracellular Delivery of siRNA. Adv. Biosyst. 2018, 2, 1800075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; Li, J.; Corey, E.; Gao, X. A ribonucleoprotein octamer for targeted siRNA delivery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.K.; Willoughby, J.L.; Chan, A.; Charisse, K.; Alam, M.R.; Wang, Q.; Hoekstra, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Kel’in, A.V.; Milstein, S.; et al. Multivalent N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated siRNA localizes in hepatocytes and elicits robust RNAi-mediated gene silencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16958–16961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avino, A.; Ocampo, S.M.; Lucas, R.; Reina, J.J.; Morales, J.C.; Perales, J.C.; Eritja, R. Synthesis and in vitro inhibition properties of siRNA conjugates carrying glucose and galactose with different presentations. Mol. Divers. 2011, 15, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Mahato, R.I. Targeted delivery of siRNA to hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells by bioconjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 2010, 21, 2119–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, M.; Nagasaki, Y.; Itaka, K.; Nishiyama, N.; Kataoka, K. Lactosylated poly(ethylene glycol)-siRNA conjugate through acid-labile beta-thiopropionate linkage to construct pH-sensitive polyion complex micelles achieving enhanced gene silencing in hepatoma cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1624–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, B.R.; Gogoi, K.; Hamil, A.S.; Palm-Apergi, C.; van den Berg, A.; Hagopian, J.C.; Springer, A.D.; Eguchi, A.; Kacsinta, A.D.; Dowdy, C.F.; et al. Efficient delivery of RNAi prodrugs containing reversible charge-neutralizing phosphotriester backbone modifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.I.; Mi, Y.; Unverzagt, C.; Gabius, H.J.; Baenziger, J.U. The asialoglycoprotein receptor clears glycoconjugates terminating with sialic acid alpha 2,6GalNAc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 17125–17129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorev, O.; Stokmaier, D.; Schwardt, O.; Cutting, B.; Ernst, B. Trivalent, Gal/GalNAc-containing ligands designed for the asialoglycoprotein receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 5216–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, A.D.; Dowdy, S.F. GalNAc-siRNA Conjugates: Leading the Way for Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2018, 28, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutschek, J.; Akinc, A.; Bramlage, B.; Charisse, K.; Constien, R.; Donoghue, M.; Elbashir, S.; Geick, A.; Hadwiger, P.; Harborth, J.; et al. Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature 2004, 432, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.T.; Kuhlmann, M.; Hvam, M.L.; Howard, K.A. Albumin-based drug delivery: Harnessing nature to cure disease. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2016, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfrum, C.; Shi, S.; Jayaprakash, K.N.; Jayaraman, M.; Wang, G.; Pandey, R.K.; Rajeev, K.G.; Nakayama, T.; Charrise, K.; Ndungo, E.M.; et al. Mechanisms and optimization of in vivo delivery of lipophilic siRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, C.; Hadwiger, P.; John, M.; Vornlocher, H.P.; Unverzagt, C. Steroid and lipid conjugates of siRNAs to enhance cellular uptake and gene silencing in liver cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 4975–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, E.; Frei, E.; Funk, D.; Becker, M.D.; Schrenk, H.H.; Muller-Ladner, U.; Fiehn, C. Native albumin for targeted drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010, 7, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Lovell, J.F.; Chen, J.; Lin, Q.; Ding, L.; Ng, K.K.; Pandey, R.K.; Manoharan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, G. Mechanistic insights into LDL nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara, H.; Nishina, K.; Yoshida, K.; Nishina, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Saito, Y.; Piao, W.; Yoshida, M.; Mizusawa, H.; Yokota, T. Efficient in vivo delivery of siRNA into brain capillary endothelial cells along with endogenous lipoprotein. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 2213–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarett, S.M.; Werfel, T.A.; Lee, L.; Jackson, M.A.; Kilchrist, K.V.; Brantley-Sieders, D.; Duvall, C.L. Lipophilic siRNA targets albumin in situ and promotes bioavailability, tumor penetration, and carrier-free gene silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6490–E6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, S.; Navaroli, D.M.; Didiot, M.C.; Cardia, J.; Pandarinathan, L.; Alterman, J.F.; Fogarty, K.; Standley, C.; Lifshitz, L.M.; Bellve, K.D.; et al. Visualization of self-delivering hydrophobically modified siRNA cellular internalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Tzekov, R.; Wang, Y.; Rodgers, A.; Cardia, J.; Ford, G.; Holton, K.; Pandarinathan, L.; Lapierre, J.; Stanney, W.; et al. Novel hydrophobically modified asymmetric RNAi compounds (sd-rxRNA) demonstrate robust efficacy in the eye. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 29, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmushkovich, T.; Monopoli, K.R.; Homsy, D.; Leyfer, D.; Betancur-Boissel, M.; Khvorova, A.; Wolfson, A.D. Functional features defining the efficacy of cholesterol-conjugated, self-deliverable, chemically modified siRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 10905–10916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassler, M.R.; Turanov, A.A.; Alterman, J.F.; Haraszti, R.A.; Coles, A.H.; Osborn, M.F.; Echeverria, D.; Nikan, M.; Salomon, W.E.; Roux, L.; et al. Comparison of partially and fully chemically-modified siRNA in conjugate-mediated delivery in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turanov, A.A.; Lo, A.; Hassler, M.R.; Makris, A.; Ashar-Patel, A.; Alterman, J.F.; Coles, A.H.; Haraszti, R.A.; Roux, L.; Godinho, B.; et al. RNAi modulation of placental sFLT1 for the treatment of preeclampsia. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirin, M.; Winkler, J. Influence of diverse chemical modifications on the ADME characteristics and toxicology of antisense oligonucleotides. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2013, 13, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooddell, C.I.; Rozema, D.B.; Hossbach, M.; John, M.; Hamilton, H.L.; Chu, Q.; Hegge, J.O.; Klein, J.J.; Wakefield, D.H.; Oropeza, C.E.; et al. Hepatocyte-targeted RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, D.B.; Ekena, K.; Lewis, D.L.; Loomis, A.G.; Wolff, J.A. Endosomolysis by masking of a membrane-active agent (EMMA) for cytoplasmic release of macromolecules. Bioconjug. Chem. 2003, 14, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, M.F.; Coles, A.H.; Biscans, A.; Haraszti, R.A.; Roux, L.; Davis, S.; Ly, S.; Echeverria, D.; Hassler, M.R.; Godinho, B.; et al. Hydrophobicity drives the systemic distribution of lipid-conjugated siRNAs via lipid transport pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscans, A.; Coles, A.; Haraszti, R.; Echeverria, D.; Hassler, M.; Osborn, M.; Khvorova, A. Diverse lipid conjugates for functional extra-hepatic siRNA delivery in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, K.; Unno, T.; Uno, Y.; Kubodera, T.; Kanouchi, T.; Mizusawa, H.; Yokota, T. Efficient in vivo delivery of siRNA to the liver by conjugation of alpha-tocopherol. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikan, M.; Osborn, M.F.; Coles, A.H.; Biscans, A.; Godinho, B.; Haraszti, R.A.; Sapp, E.; Echeverria, D.; DiFiglia, M.; Aronin, N.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of Parenchymal Retention and Efficacy of a Metabolically Stable O-Phosphocholine-N-docosahexaenoyl-l-serine siRNA Conjugate in Mouse Brain. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017, 28, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willibald, J.; Harder, J.; Sparrer, K.; Conzelmann, K.K.; Carell, T. Click-modified anandamide siRNA enables delivery and gene silencing in neuronal and immune cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12330–12333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Ishino, M.; Loewenstein, P.M. Mutational analysis of HIV-1 Tat minimal domain peptides: Identification of trans-dominant mutants that suppress HIV-LTR-driven gene expression. Cell 1989, 58, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochiantz, A. Getting hydrophilic compounds into cells: Lessons from homeopeptides. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996, 6, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooga, M.; Hallbrink, M.; Zorko, M.; Langel, U. Cell penetration by transportan. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.L.; Ali, A.; Chu, C.Y.; Cao, H.; Rana, T.M. Visualizing a correlation between siRNA localization, cellular uptake, and RNAi in living cells. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, T.J.; Harel, S.; Arboleda, V.A.; Prunell, G.F.; Shelanski, M.L.; Greene, L.A.; Troy, C.M. Highly efficient small interfering RNA delivery to primary mammalian neurons induces MicroRNA-like effects before mRNA degradation. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10040–10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratovska, A.; Eccles, M.R. Conjugate for efficient delivery of short interfering RNA (siRNA) into mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 2004, 558, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschos, S.A.; Jones, S.W.; Perry, M.M.; Williams, A.E.; Erjefalt, J.S.; Turner, J.J.; Barnes, P.J.; Sproat, B.S.; Gait, M.J.; Lindsay, M.A. Lung delivery studies using siRNA conjugated to TAT(48-60) and penetratin reveal peptide induced reduction in gene expression and induction of innate immunity. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, E.S.; Aguilera, T.A.; Jiang, T.; Ellies, L.G.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Wong, E.H.; Gross, L.A.; Tsien, R.Y. In vivo characterization of activatable cell penetrating peptides for targeting protease activity in cancer. Integr. Biol. (Camb.) 2009, 1, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.Q.; Gao, W.; Xiang, B.; Qi, X.R. Enhancing cellular uptake of activable cell-penetrating peptide-doxorubicin conjugate by enzymatic cleavage. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, I.; Teixido, M.; Giralt, E. Building Cell Selectivity into CPP-Mediated Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 1456–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; He, J.; Yi, H.; Xiang, G.; Chen, K.; Fu, B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G. siRNA suppression of hTERT using activatable cell-penetrating peptides in hepatoma cells. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35, e00181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Olson, E.S.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Roy, M.; Jennings, P.A.; Tsien, R.Y. Tumor imaging by means of proteolytic activation of cell-penetrating peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17867–17872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, S.A.; Hansen, M.B.; Oerlemans, R.A.; van Hest, J.C.; Lowik, D.W. Enzyme-Activatable Cell-Penetrating Peptides through a Minimal Side Chain Modification. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaziova, Z.; Baumann, V.; Winkler, A.M.; Winkler, J. Chemically defined polyethylene glycol siRNA conjugates with enhanced gene silencing effect. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, F.; Yang, C.; Dagnaes-Hansen, F.; Schaffert, D.H.; Kjems, J.; Gao, S. Optimized siRNA-PEG conjugates for extended blood circulation and reduced urine excretion in mice. Theranostics 2013, 3, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, K.L.; Nguyen, T.H.; Chang, C.W.; Bulmus, V.; Davis, T.P.; Maynard, H.D. Reversible siRNA-polymer conjugates by RAFT polymerization. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2008, 3245–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che Harun, N.F.; Takemoto, H.; Nomoto, T.; Tomoda, K.; Matsui, M.; Nishiyama, N. Artificial Control of Gene Silencing Activity Based on siRNA Conjugation with Polymeric Molecule Having Coil-Globule Transition Behavior. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 1961–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A.W.; Huang, F.; McCormick, C.L. Rational design of targeted cancer therapeutics through the multiconjugation of folate and cleavable siRNA to RAFT-synthesized (HPMA-s-APMA) copolymers. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, D.B.; Lewis, D.L.; Wakefield, D.H.; Wong, S.C.; Klein, J.J.; Roesch, P.L.; Bertin, S.L.; Reppen, T.W.; Chu, Q.; Blokhin, A.V.; et al. Dynamic PolyConjugates for targeted in vivo delivery of siRNA to hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12982–12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, H.; Miyata, K.; Hattori, S.; Ishii, T.; Suma, T.; Uchida, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Kataoka, K. Acidic pH-responsive siRNA conjugate for reversible carrier stability and accelerated endosomal escape with reduced IFNalpha-associated immune response. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 6218–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, R.G.; Poslusney, M.; Busuek, M.; Williams, J.M.; Garbaccio, R.; Leander, K.; Walsh, E.; Howell, B.; Sepp-Lorenzino, L.; Riley, S.; et al. Novel endosomolytic poly(amido amine) polymer conjugates for systemic delivery of siRNA to hepatocytes in rodents and nonhuman primates. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Dohmen, C.; Philipp, A.; Kiener, D.; Maiwald, G.; Scheu, C.; Ogris, M.; Wagner, E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a bioresponsive and endosomolytic siRNA-polymer conjugate. Mol. Pharm. 2009, 6, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, S.E.; Guidry, E.N. Liver-Targeted SiRNA Delivery Using Biodegradable Poly(amide) Polymer Conjugates. In SiRNA Delivery Methods: Methods and Protocols; Shum, K., Rossi, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Lu, X.; Tan, X.; Jia, F.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Li, Y.; Silva, D.O.; Schrekker, H.S.; et al. Molecular spherical nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4340–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, J.I.; Auyeung, E.; Mirkin, C.A. Spherical nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1376–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkin, C.A.; Stegh, A.H. Spherical nucleic acids for precision medicine. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giljohann, D.A.; Seferos, D.S.; Prigodich, A.E.; Patel, P.C.; Mirkin, C.A. Gene regulation with polyvalent siRNA-nanoparticle conjugates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2072–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, C.H.; Melamed, J.R.; Day, E.S. Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticles: Therapeutic Potential. BioDrugs 2018, 32, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Hao, L.; Narayan, S.P.; Auyeung, E.; Mirkin, C.A. Mechanism for the endocytosis of spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7625–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, J.R.; Riley, R.S.; Valcourt, D.M.; Billingsley, M.M.; Kreuzberger, N.L.; Day, E.S. Quantification of siRNA Duplexes Bound to Gold Nanoparticle Surfaces. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1570, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melamed, J.R.; Kreuzberger, N.L.; Goyal, R.; Day, E.S. Spherical Nucleic Acid Architecture Can Improve the Efficacy of Polycation-Mediated siRNA Delivery. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemati, H.; Ghahramani, M.H.; Faridi-Majidi, R.; Izadi, B.; Bahrami, G.; Madani, S.H.; Tavoosidana, G. Using siRNA-based spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates for gene regulation in psoriasis. J. Control. Release 2017, 268, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Giljohann, D.A.; Chen, D.L.; Massich, M.D.; Wang, X.Q.; Iordanov, H.; Mirkin, C.A.; Paller, A.S. Topical delivery of siRNA-based spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates for gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11975–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.A.; Day, E.S.; Ko, C.H.; Hurley, L.A.; Luciano, J.P.; Kouri, F.M.; Merkel, T.J.; Luthi, A.J.; Patel, P.C.; Cutler, J.I.; et al. Spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle conjugates as an RNAi-based therapy for glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 209ra152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, X. Hollow carbon nanospheres as a versatile platform for co-delivery of siRNA and chemotherapeutics. Carbon 2017, 121, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.L.; Scott, A.W.; Hao, L.; Mirkin, S.E.; Liu, G.; Mirkin, C.A. Hollow spherical nucleic acids for intracellular gene regulation based upon biocompatible silica shells. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3867–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Thomas, M.; Lin, P.; Cheng, J.X.; Matei, D.E.; Wei, A. siRNA Delivery Using Dithiocarbamate-Anchored Oligonucleotides on Gold Nanorods. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banga, R.J.; Chernyak, N.; Narayan, S.P.; Nguyen, S.T.; Mirkin, C.A. Liposomal spherical nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9866–9869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, K.; Hoffmann, K.; Kewalramani, S.; Brodin, J.D.; Moreau, L.M.; Mirkin, C.A.; Olvera de la Cruz, M.; Bedzyk, M.J. Defining the Structure of a Protein-Spherical Nucleic Acid Conjugate and Its Counterionic Cloud. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medarova, Z.; Pham, W.; Farrar, C.; Petkova, V.; Moore, A. In vivo imaging of siRNA delivery and silencing in tumors. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derfus, A.M.; Chen, A.A.; Min, D.H.; Ruoslahti, E.; Bhatia, S.N. Targeted quantum dot conjugates for siRNA delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, N.W.; Liu, Z.; Dai, H. Functionalization of carbon nanotubes via cleavable disulfide bonds for efficient intracellular delivery of siRNA and potent gene silencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12492–12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, L.; Tang, X. Dextran-Conjugated Caged siRNA Nanoparticles for Photochemical Regulation of RNAi-Induced Gene Silencing in Cells and Mice. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, A.D.; Bola, G.; Lee, A.C.; MacLachlan, I. Design of noninflammatory synthetic siRNA mediating potent gene silencing in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.H.; Mok, H.; Oh, Y.K.; Park, T.G. siRNA conjugate delivery systems. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strategy | siRNA Bioconjugate | Conjugate Site | Linker * | siRNA Scaffold | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand siRNA conjugate | Antibody-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | SMCC (noncleavable) or SPDP (disulfide) | siRNA | [34] |

| Fab-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | DMSS (disulfide) | siRNA | [35] | |

| IGF1 mimetic peptide-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | C6 carbon (noncleavable) | siRNA | [40] | |

| cRGD-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | SMCC (noncleavable) | siRNA | [41,42,43] | |

| Octreotide-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Click linker (noncleavable) | siRNA | [44] | |

| Tat-AHNP-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Click linker (noncleavable) | siRNA | [44] | |

| cRGD-siRNA-spermine | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [45] | |

| LHRH peptide-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | PEG-SPDP (disulfide) | siRNA | [46] | |

| Anti-PSMA aptamer-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | RNA oligo (cleavable by Dicer) | siRNA | [25,56] | |

| CpG1668-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | C6 carbon (noncleavable) | siRNA | [53] | |

| Folate-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | PEG disulfide | siRNA | [60,61] | |

| DUPA-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [61,62,63] | |

| M6P-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | PEG disulfide | siRNA | [65,66] | |

| Lac-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | β-thiopropionate (acid cleavable) | siRNA | [67] | |

| GalNac-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | trans-4-hydroxyprolinol (noncleavable) | siRNA | [63,68,69] | |

| Lipid siRNA conjugate | Chol-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | trans-4-hydroxyprolinol (noncleavable) | siRNA | [72,74,75,78,79] |

| hsiRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | TEG (noncleavable) | aiRNA | [80,81,82,83,84] | |

| α-tocopherol-siRNA | 5′ end of antisense strand | phosphodiester (noncleavable) | DsiRNA | [90] | |

| DCA, EPA or PC-DCA-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | C7 linker (noncleavable) | aiRNA | [89,91] | |

| Anandamide-siRNA | 3′ base of sense strand | Click linkage (noncleavable) | siRNA | [92] | |

| CPP siRNA conjugate | Tat-siRNA | 3′ end of antisense strand | HBFC (noncleavable) | siRNA | [96] |

| Transportan-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [97,98] | |

| Penetratin-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [97,98] | |

| Polymer siRNA conjugate | PEG-siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | C6 carbon (noncleavable) | siRNA | [107] |

| PNIPAAm-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Click linker (noncleavable) | siRNA | [109] | |

| HPMA-s-APMA-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [110] | |

| Dynamic polyconjugate | 5′ end of sense strand | SATA (disulfide) | siRNA | [111,113,114,115] | |

| Releasable/enzyme-disrupting conjugate | n/a | CDM (acid cleavable) | siRNA | [112] | |

| Nanoparticle siRNA conjugate | Spherical siRNA | 3′ end of sense strand | Spacer 18 thiol-gold bond (noncleavable) | siRNA | [119] |

| Magnetic nanoparticles-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | MBS (noncleavable) | siRNA | [132] | |

| Quantum dot-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | SMCC (noncleavable) or SPDP (cleavable) | siRNA | [133] | |

| Nanotube-siRNA | 5′ end of sense strand | Disulfide | siRNA | [134] | |

| Dextran cage-siRNA | 5′ end of sense and antisense strand | Photocleavable linker | siRNA | [135] |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tai, W. Current Aspects of siRNA Bioconjugate for In Vitro and In Vivo Delivery. Molecules 2019, 24, 2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24122211

Tai W. Current Aspects of siRNA Bioconjugate for In Vitro and In Vivo Delivery. Molecules. 2019; 24(12):2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24122211

Chicago/Turabian StyleTai, Wanyi. 2019. "Current Aspects of siRNA Bioconjugate for In Vitro and In Vivo Delivery" Molecules 24, no. 12: 2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24122211

APA StyleTai, W. (2019). Current Aspects of siRNA Bioconjugate for In Vitro and In Vivo Delivery. Molecules, 24(12), 2211. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24122211