Abstract

Improving life satisfaction is consistent with the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals. Although there are many studies examining life satisfaction, research on the influencing mechanisms remains a hot topic and scholars hope to explore more aspects that improve life satisfaction. The purpose was to explore how the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction are mediated by positive and negative affect. We collected longitudinal data from 909 respondents participating in the 2008 and 2012 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). We used the first-order difference method and structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis to evaluate the validity of the proposed hypotheses. Our results demonstrated that social effort-reward imbalance was positively related to negative affect, and negatively related to positive affect. Positive affect was positively related to life satisfaction, while negative affect was negatively related to life satisfaction. The findings also indicated that positive and negative affect completely mediated the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction. This study has made a contribution to the research on the influencing mechanism of life satisfaction from the aspects of theory and practice. Longitudinal data ensured that the conclusions were more reliable so that the study could provide useful suggestions for improving life satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Social effort-reward imbalance affects a high proportion of people globally [1,2,3,4,5]. The population of highly developed countries, such as Japan and the United States, is rapidly aging [6] and these aging workforces are an important aspect of the sustainable employability and labor market which Goal 8 of the United Nations sustainable development goals is focused on (sustainable development goal 8) [7]. With aging societies worldwide, a greater proportion of the labor market will be made up of aging workforces, and the need to improve older adults’ sustainable employability means long-term abilities to work and remain employed in the workplace are highlighted [8,9]. How to engage and retain aging workforces are crucial questions internationally [10]. Moreover, as aging workforces are characterized by a reduced skill level and mobility, the phenomenon of social effort-reward imbalance among them is becoming more serious [11]. A potentially detrimental influence of effort-reward imbalance was underlined in a large cross-country study about aging workforces [12]. Studies have shown that social effort-reward imbalance can increase work stress while decreasing job satisfaction, which in turn indirectly leads to physical and mental health problems, such as increased cardiovascular risk, type 2 diabetes, and mental illness [13,14]. In addition, workplace related factors such as depression, sick leave, presenteeism, and job burnout are directly related to social effort-reward imbalance [15,16,17]. Above all, we believe that it is very important and of great practical significance to pay attention to effort-reward imbalance of aging workforces. Since life satisfaction has become an important research field [18,19,20,21], we focused on the influence of social effort-reward imbalance to life satisfaction on aging workforces. On the one hand, life satisfaction is considered important by many aging standards [22]. The World Health Organization (2002) indicated the aging process increases the potential of individuals to support themselves and helps them achieve their physical, social, and happiness potential throughout their lives [23]. Therefore, studying life satisfaction can help reveal the aging process. On the other hand, because older individuals tend to give a higher priority to achieving their goals in life [24], paying attention to the effort-reward imbalance of aging workforces, such as taking care of family and volunteer services, may have an impact on the sustainable employability of older adults. Employment of aging workforces is consistent with the UN’s sustainable development goals. Previous studies have shown that older people who continue to work can improve their life satisfaction [22,25,26] and reemployment after retirement is conducive to improving life satisfaction among older people [27], thus further improving their quality of life. On the other hand, there is a very close relationship between life satisfaction and sustainable employability. Some studies have shown that improving the life satisfaction of aging workforces can help them make better choices in employment/reemployment [22,27]. This study shifts focus to life, hoping to provide better suggestions for sustainable employability of aging workforces, which is the novelty of the research. As mentioned above, aging workforces are becoming the main source of social labor and, even if formal ethical mechanisms have been implemented, unethical behaviors often occur [28], including unfair treatment [29]. Consequently, we chose the aging workforce in the United States as our research population to study problems regarding effort-reward imbalance in life and we aimed to address problems of effort-reward imbalance, improve aging workforces’ life satisfaction, so as to provide suggestions for their sustainability and sustainable employability.

Effort-reward imbalance is a negative set of circumstances where employees are treated in unfair ways [30]. Many studies highlighted that negative events can lead to negative affect [31]. Yet, with increased attention in positive psychology, we consider the impact of positive affect to also be very important. With the development of construct of affect, individuals’ affects have usually been classified as positive and negative affect [32,33], and they were regarded as two relatively independent affects. Specifically, negative affect has been described as the extent to which a person experiences unpleasant participation, subjective distress, and emotional pain [33]. Positive affect, typically featuring happiness, inspiration, or enthusiasm, is a mental state best described by enjoyable engagement with the environment [34,35]. Previous experiments and cross-cultural studies have confirmed the causal relationship between affect and life satisfaction [36,37]. Therefore, in this study, we examined the impact of social effort-reward imbalance on positive and negative affect to see how closely affects are related to social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction. Our research can also contribute to the antecedents and consequences of positive affect. At the same time, our study uses two years of data to perform a longitudinal study, which echoes Kuppens’s research to better demonstrate the causal relationship between affects and life satisfaction [36].

The Feelings-as-information theory [37] argues that emotions (including moods, affects, metacognitive experiences, and bodily sensations) can serve as a source of information to provide a basis for judging and processing events or goals. Affects reflect the assessment source [38], and some researchers demonstrated that affects are the result of individual continued implicit evaluation of a certain target [39]. This is one kind of assessment people make from their state. This kind of assessment is a source of affect and, whereas positive affect will be generated when social effort-reward balance occurs, negative affect will be generated when social effort-reward imbalance occurs. Meanwhile, as the basis for people to judge events or goals, affects will have an impact on people’s evaluation of life satisfaction.

From what has been discussed above, we found that many scholars paid close attention to aging workforces in the workplace issues. However, this study shifts focus to life to fill in the main literature gap. This paper evaluates the impact of social effort-reward imbalance on life satisfaction of aging workforces and whether positive and negative affect mediate the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction. As the population is rapidly aging in many countries, aging workforces have gradually become the main source of social labor. Through our research into the aging workforce in the United States and the result of our longitudinal study data, on the one hand, we hope to supplement the research content in this field, as longitudinal data can add additional value to our study; on the other hand, we give recommendations for improving life satisfaction of aging workforces and their sustainable employability in developed countries and some large developing countries in the world, which is the primary goal of the study.

2. Theoretical Background, Literature Review, and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Social Effort-Reward Imbalance and Positive and Negative Affect

In the late 1990s, Siegrist put forward effort-reward imbalance. Individual investment of time and energy in work needs to be paid by salary, respect, and professional development. However, once the organization fails to meet the employees’ demands, the employees may feel a sense of imbalance which could lead to a change in their working state, such as dissatisfaction [40]. Fahlen et al. conducted a survey of 789 male and 214 female employees and found that social effort-reward imbalance was related to an increase in fatigue [41]. Tsutsumi et al. took 1103 Japanese medical practitioners as their research sample and showed that 57% of the doctors had social effort-reward imbalance, which led to an increase in depression [42]. In addition, some studies, including those by Bakker and Schulz, proved that social effort-reward imbalance could significantly predict emotional exhaustion [17,43].

With the development of construct of affect, those captured by individuals were usually divided as either positive or negative because they were regarded as two separately independent processes [32,33]. Schwarz pointed out that an individual’s assessment of his or her own state influences the production of affects [37]. Similarly, Keltner thought affects reflect the source of assessment [38]. This paper studied the different influences of social effort-reward imbalance on positive and negative affect. Based on previous studies and the above analysis, we put forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Social effort-reward imbalance is negatively related to positive affect.

Hypothesis 2.

Social effort-reward imbalance is positively related to negative affect.

2.2. Social Effort-Reward Imbalance and Life Satisfaction

The study of life satisfaction emerged in the United States in the 1950s and many studies regard life satisfaction of aging populations as an important indicator to measure and control the mental health of the older population. Before we talk about this, we should know that subjective well-being is composed of life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect [44], each of the specific constructs need to be understood in their own right [45]. Physical illness, aging, and interpersonal communication will all have a certain impact on the psychological state among older adults, and especially on their life satisfaction [46]. Life satisfaction, mostly defined from the perspective of life quality and psychological status, refers to people’s subjective evaluation and psychological satisfaction in their own life status and reflects people’s subjective feelings under certain living conditions [47]. Psychosocial factors have been well proved to have a significant contribution to health and wellbeing [48]. In the studies on life satisfaction of older adults, research has shown that their social effort-reward imbalance is more severe because of their age [11]. Similarly, Bryant pointed out that older adults suffer from more pressure when they are older and their life satisfaction will be relatively lower [49]. In addition, studies have shown that when aging workforces suffer from a social effort-reward imbalance in the workplace, their life satisfaction or quality of life will decrease [50,51,52]. Therefore, we can put forward the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Social effort-reward imbalance is negatively related to life satisfaction.

2.3. Positive Affect, Negative Affect, and Life Satisfaction

Many studies have shown that positive and negative affect play an important role in the workplace [53,54] and some have emphasized the significant influence of positive and negative affect in general life [55]. Feelings-as-information theory shows that affects can alter people’s judgment on life satisfaction, and studies have also confirmed the causal relationship between affects and life satisfaction [36,37], which will affect the judgment on life satisfaction of older adults. Some studies also suggest that life satisfaction is a multi-dimensional structure composed of several independent parts, including the existence of positive affect and the lack of negative affect [45,56]. In addition, Schwarz suggested that different affects have different impacts on life satisfaction judgment, with positive affect increasing life satisfaction and negative affect decreasing life satisfaction [57]. Based on the above theory and empirical research evidence, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4.

Positive affect is positively related to life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5.

Negative affect is negatively related to life satisfaction.

2.4. Feelings-as-Information Theory

Feelings-as-information theory was put forward by Schwarz and Clore in 1983 [57]. It conceptualizes subjective feelings, to explore the role of these feelings on people’s judgement. This theory assumes that people tend to regard their feelings as a source of information which can influence subsequent judgment and different feelings provide various types of information [57]. For this theory, Frijda proposed that affects are the result of individual continued implicit evaluation of a certain target, and they have a discernible direction [39]. Affects reflect the source of the assessment [38]. The experience of an affect means that there is a set of specific evaluation criteria and a specific affect reflects an individual’s evaluation of a specific event or object [38].

Feelings-as-information theory solves the problem of the role of affect in the process of judging and processing events and proposes that affect can serve as a source of information to provide a basis for judging and processing events or goals. When people are under positive affect, the will to invest in risky stock may lead to optimistic estimates. Hirshleifer observed that the weather in 26 countries had an impact on the stock market. When it was sunny in a city which contained the country’s main stock exchange, people would experience a positive affect, which resulted in a rise in the stock market [58]. When making evaluative judgments, our affect reflects the state of the situation [59]. Subsequently, a positive affect conveys to us that the current situation is good, while a negative affect conveys that the current situation is problematic.

2.5. The Mediating Role of Positive Affect and Negative Affect

Considering that positive and negative affect have a close inter-relationship, they were frequently used as mediators in previous research models [60,61,62,63,64]. We hypothesize that positive and negative affect play a mediating role between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction. In other words, social effort-reward imbalance will reduce life satisfaction by affecting positive and negative affect. In the previous analysis, according to Feelings-as-information theory, an aging workforce will evaluate whether their social effort-reward is balanced. This evaluation is the source of affect generation and positive affect will be generated when social effort-reward balance is achieved. Negative affect will be generated when social effort-reward imbalance occurs. Subsequently, affects (as the basis for people to judge things) will alter the judgment of an aging workforce on life satisfaction, i.e., life satisfaction will be increased or decreased. Therefore, we infer that positive and negative affect mediates the effect of social effort-reward imbalance on life satisfaction and make the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6.

Positive affect mediates the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 7.

Negative affect mediates the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction.

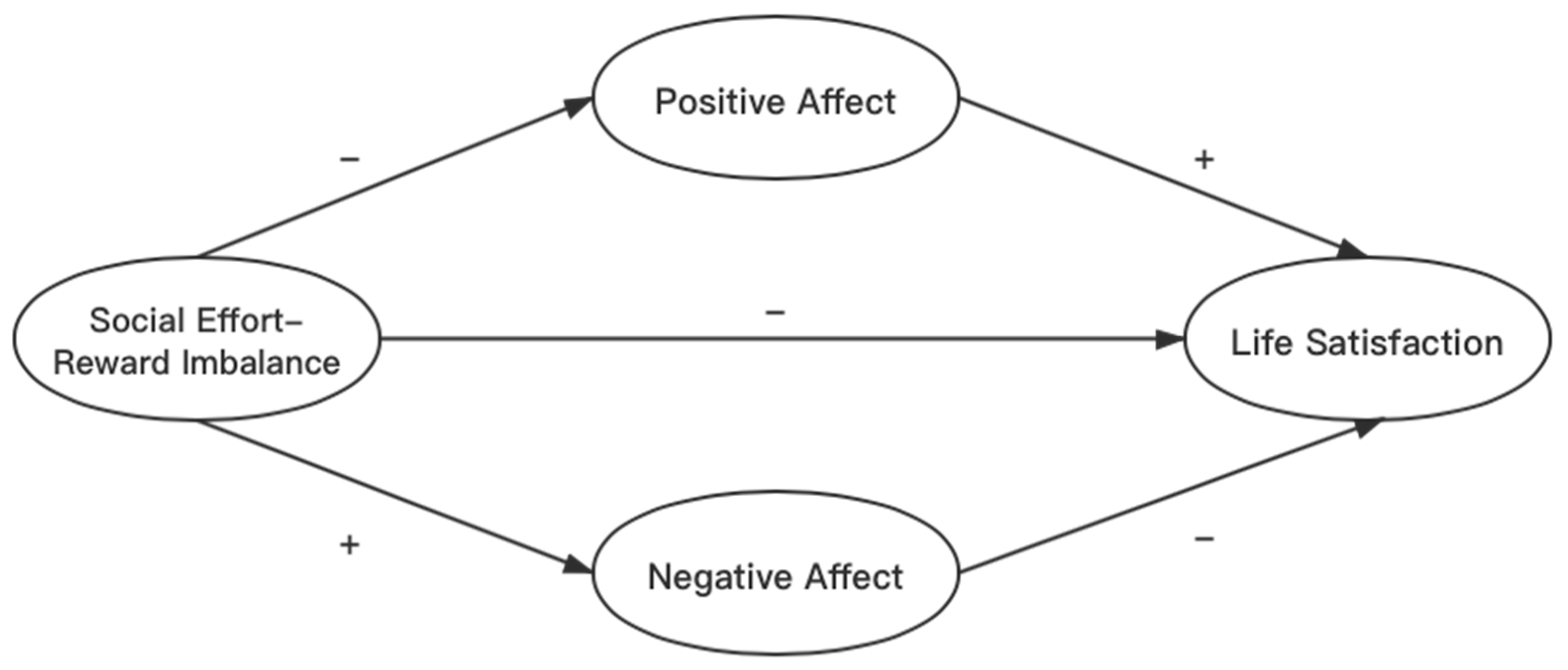

Above all, we constructed a conceptual model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Source

Longitudinal data were collected from the 2008 and 2012 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is widely recognized as the best source of publicly available data on the aging population of the United States. HRS was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration of the United States, and was conducted by the University of Michigan, U.S. [65,66].

In 2006, the HRS added a Psychological and Life Questionnaire (PLQ) to the core biennial survey, which was administered to a random 50% of core panel participants. The PLQ was developed by the HRS psychosocial Working Group and includes scales measuring effort-reward imbalance, life satisfaction, and positive and negative affect. More details about the HRS are available online (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu, accessed on 10 December 2021).

In the 2008 and 2012 wave of HRS, data from the Lifestyle and Behavior Questionnaire (LBQ) were available for 17,217 and 20,554 participants, respectively. Among these participants, 909 participants were currently employed both years and answered at least one question on each questionnaire. Data from the 909 participants were analyzed in this study (Table 1, the missing value is within 2.8%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample population (N = 909).

3.2. Variables and Measures

Social Effort-Reward Imbalance. Social effort-reward balance was assessed using a 3-item scale [30,67]. The three items assess the balance that participants experience in the efforts that they put forth socially (in relationships and activities) and the rewards received from this effort. The data in 2008 and 2012 wave showed reasonable reliability (Cronbach α = 0.78; Cronbach α = 0.77). For example, the item, “In my current major activity (job, looking after home, voluntary work) I have always been satisfied with the rewards I received for my efforts” evaluates social effort-reward balance. A 5-point Likert scale was used to record these responses, 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. In later analyses, the mean of the total scale score was reported, higher scores indicated higher social effort-reward balance, and by reverse-coding higher scores indicated higher social effort-reward imbalance.

Life Satisfaction. Life satisfaction was assessed using a 5-item scale [68,69]. The 5-item scale is a well-established measure of self-evaluated life satisfaction that has been used extensively in international comparative studies. Data from the scale in 2008 and 2012 were reported to have high reliability (Cronbach α = 0.88; Cronbach α = 0.88). For example, “In most ways my life is close to ideal” evaluates life satisfaction. Responses were scored on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. In these analyses, the mean of the total scale score was used and higher scores indicated higher life satisfaction.

Positive and Negative Affect. Positive and negative affect was assessed using a 25-item scale. In 2008, HRS researchers began to pick up 25 items to evaluate positive and negative affect from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form (PAN AS-X) [33]. Some items in this scale were collected from the previous study in this research field [70,71]. The scale is made up of 25 items. Positive affect was defined as enthusiastic, active, interested, proud, attentive, inspired, hopeful, alert, and so on. Positive affect data in 2008 and 2012 wave showed high reliability (Cronbach α = 0.92; Cronbach α = 0.90). Negative affect was defined as afraid, scared, guilty, upset, nervous, jittery, sad, distressed and so on. Negative affect data in 2008 and 2012 wave showed high reliability (Cronbach α = 0.89; Cronbach α = 0.90). A 5-point Likert scale was used to record these responses, 1 = very much and 5 = not at all. In later analyses, the mean of the total scale score was reported, and by reverse-coding higher scores indicated higher positive and lower negative affect.

Control variable. Age meant the age in years at baseline. Gender was coded as 1 = men and 2 = women. Education meant the number of years being educated.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0 were used for statistical analysis comprising descriptive analysis and path analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was used to distinguish relationships between Δ social effort-reward imbalance, Δ positive affect, Δ negative affect, and Δ life satisfaction (the “Δ” means the change value between 2008 and 2012).

Before SEM, missing values for observed indicators were imputed by using expectation maximization (EM) implementation of maximum likelihood. This method is an effective method for maximum likelihood estimation [72]. It has one important premise: it works for a large sample. The number of valid samples is sufficient to ensure that the ML estimate is asymptotically unbiased and normally distributed, and it is more attractive than deleting cases and single value interpolation [73]. Moreover, we established numerous CFA models to test the discriminative validity of model constructs.

Then, we used the first-order difference method based on the assumption of fixed effect [74]. Relying on differences between the independent variable and the dependent variable of an identical respondent in the time dimension, the difference method is adopted to eliminate time-invariant factors other than observations. In the model, first, the first-order difference of the items of each construct was carried out according to the year, and then the latent variables of each construct were calculated by regression of the values after the difference of each item. The measurement errors of each construct could be eliminated theoretically by this method. Finally, we got the explanatory variable, using T2-T1, so that the explanatory variable can show the change from 2008 to 2012, which has higher value. For example, in a difference mode with Δ social effort-reward imbalance, an explanatory variable corresponds to the change value.

Since SEM has potential superiorities of choice in analyzing path graphs when they involve latent variables with multiple indicators [75]. To determine whether Δ positive affect and Δ negative affect have an indirect effect on the relation between Δ social effort-reward imbalance and Δ life satisfaction in this study, SEM was used to test the mediating effect in the research model by using maximum likelihood method estimation [76]. The criteria used to evaluate good global fit were a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08, normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values of 0.9 or higher [77], and the chi-squared test (X2).

A non-parametric resampling procedure was used to assess mediation with SPSS INDIRECT Macros Model 4 [78]. This method was acknowledged as the most straightforward bootstrapping method to acquire confidence intervals for indirect effects [79]. If the indirect effect was significant and the confidence interval did not include zero, the results can prove the mediation effect [8].

4. Results

4.1. Means (SD) for Δ Social Effort-Reward Imbalance, Δ Positive Affect, Δ Negative Affect, and Δ Life Satisfaction

Table 2 shows the mean (SD) values (the following values represent absolute values) for Δ social effort-reward imbalance, Δ positive affect, Δ negative affect, and Δ life satisfaction. The means for the three Δ social effort-reward imbalance items were low and ranged from 0.04 (“I have always been satisfied with the balance between what I have given my partner and what I have received in return”; SD = 1.101) to 0.08 (“In my current major activity (job, looking after home, voluntary work) I have always been satisfied with the rewards I received for my efforts”; SD = 1.201). The mean for the Δ positive affect items was lower than that for the Δ negative affect items. The fifth Δ positive affect item (“Interested”) had the lowest score (M = 0.001; SD = 1.048), and the second and third item (“Enthusiastic”; “Active”) had the highest score (M = 0.08; SD = 1.174, 1.110). The second Δ negative affect item (“Upset”) had the highest score (M = 0.09; SD = 0.997), and the ninth item (“Ashamed”) had the lowest score (M = 0.003; SD = 0.678). The means for the five Δ life satisfaction items ranged from 0.04 (“I am satisfied with my life”; SD = 1.688) to 0.16 (“The conditions of my life are excellent”; SD = 1.810).

Table 2.

Means (SD) for Δ social effort-reward imbalance (ERI), Δ positive affect (PA), Δ negative affect (NA), and Δ life satisfaction (LS).

4.2. Discriminative Validity Test

We used Amos to do multi-layer nested CFA analysis, and found that the model with best model fit is the four-factors CFA model, followed by three-factors CFA model, two-factors model, and one-factor model, confirming the discriminative validity between positive affect and negative affect, between life satisfaction and positive affect, as well as between negative affect and social effort-reward imbalance (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of discriminative validity based on CFA.

4.3. Model Fit

Several studies [80,81] recommended analyzing the measurement model before construction. Before analyzing these hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the overall measurement model according to the literature. The CFA results reported that the X2 value was statistically significant (X2 = 1378.889, p = 0.000). As is stated above, a number of indicators should be considered when evaluating the overall model fit. In our model, all the model fit indices indicated that the measurement model had acceptable fit with the dataset (X2 = 1378.889, X2/df = 3.482, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.885, NFI = 0.850, TLI = 0.871). The overall model was proven just acceptable with a good fit for data analysis via a structural model. As can be seen above, because all indices were above or very close to related criteria, the conceptual model can be statistically accepted, and many studies have shown that such a model is acceptable [82,83,84,85,86].

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Table 4 reports the correlations among the variables. The results demonstrate that Δ positive affect is negatively associated with Δ social effort-reward imbalance (r = −0.143, p < 0.01), and Δ negative affect is positively associated with Δ social effort-reward imbalance (r = 0.145, p < 0.01). Δ life satisfaction has a negative correlation with Δ social effort-reward imbalance (r = −0.106, p < 0.01) and Δ negative affect (r = −0.195, p < 0.01), but has a positive correlation with Δ positive affect (r = 0.201, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the study variables.

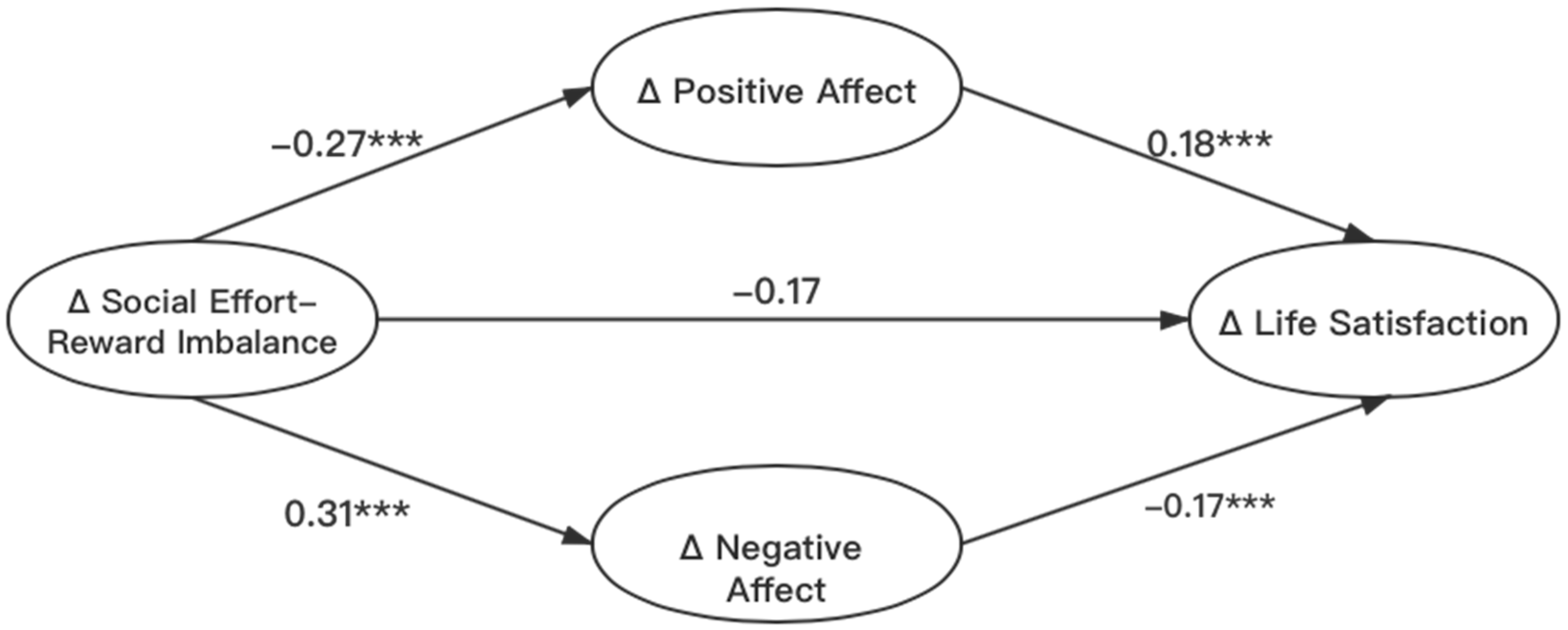

In the final longitudinal model, our results show that Δ positive affect was significantly positively correlated with Δ life satisfaction (β = 0.18, p < 0.001) and inversely related to Δ social effort-reward imbalance (β = −0.27, p < 0.001). It means hypotheses 4 and 1 are both empirically supported. Δ negative affect was significantly positively correlated with Δ social effort-reward imbalance (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) and inversely related to Δ life satisfaction (β = −0.17, p < 0.001). It means hypotheses 2 and 5 are empirically supported. In SPSS, mediation analysis with model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used to determine whether Δ positive affect and Δ negative affect mediated the association between Δ social effort-reward imbalance and Δ life satisfaction (Table 5). The analysis showed that Δ social effort-reward imbalance was related to Δ positive affect, which in turn was related to Δ life satisfaction (point estimate of indirect effects = −0.0349, SE = 0.0123, 95% BLLCI ULCI = −0.0606 to −0.0129). Similarly, Δ social effort-reward imbalance was related to Δ negative affect, which in turn was related to Δ life satisfaction (point estimate of indirect effects = −0.0344, SE = 0.0131, 95% BLLCI ULCI = −0.0639 to −0.0122). The association between Δ social effort-reward imbalance and Δ life satisfaction was completely mediated by Δ positive affect and Δ negative affect. Therefore, hypotheses 6 and 7 are both supported (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Direct effect, indirect effects, and total effects in SEM.

Figure 2.

Mediator model of how Δ social effort-reward imbalance influences Δ life satisfaction via Δ positive and Δ negative affect. Note. *** p < 0.001.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary and Implications

This study tested the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction, and the mediating role of positive affect and negative affect. This study examined the data collected from 909 aging workers in total from two waves. We believe there are significant empirical findings and implications worth highlighting.

The results in this study showed that all relations are longitudinal. First, the results showed that change in social effort-reward imbalance was positively related to change in negative affect. This finding of the study is consistent with previous research [30,31]. Second, change in social effort-reward imbalance is negatively related with change in positive affect and the rise of social effort-reward imbalance reduces the generation of positive affect. In other words, positive affect will be generated when workers feel balance between social effort-rewards [87]. Third, the results showed that change in positive affect was positively related to change in life satisfaction and change in negative affect was negatively related to change in life satisfaction. This result is consistent with existing research findings [36,88,89,90] and is also backed up by the Feelings-as-information theory [37]. In addition, the results showed that change in positive and negative affects play a complete mediating role between change in social effort-reward imbalance and change in life satisfaction, meaning the change in social effort-reward imbalance affects change in life satisfaction through change in positive and negative affect. Therefore, we can say that social effort-reward imbalance may not increase or decrease life satisfaction directly. Social effort-reward imbalance can indirectly impact life satisfaction by influencing the increase or decrease of individuals’ positive and negative affect.

This research can make a contribution to theory and practice aspects. First, our results validate and enrich the Feelings-as-information theory as the analysis of the study was based on the content and meaning of Feelings-as-information theory. The research results support the theory that people rely on emotional experience to assess their life satisfaction [37]. In addition, our results provide a new perspective for study of the Feelings-as-information theory as they show that effort-reward imbalance from society and family will alter individual affect. Furthermore, individual affect will affect their assessment of life satisfaction.

Second, social effort-reward imbalance cognition has mainly been based on a single large-scale study of the general population in the past [12]. We focused on the aging workforce in this study as this specific population is quickly becoming the main source of social labor. Our results provide a new idea for exploring the influence mechanism of social effort-reward imbalance, remind managers to pay more attention to social effort-reward imbalance of specific groups around them, and help to solve the problems regarding social effort-reward imbalance of vulnerable groups.

Third, affects are very important in judging a person’s life satisfaction [36,91,92,93] and some researchers hold the view that affects can play a mediating role between psychological perception and life satisfaction [94]. However, there are few studies that focus on specific psychological perception factors which lead to positive and negative affects at the same time in one study [95]. This study highlighted positive and negative affect mediators and emphasized the focus on affects for the mechanism of the influence on life satisfaction, advocating for managers to improve employees’ life satisfaction by regulating personal affects. Furthermore, it adds to the literature by exploring factors that lead to affects: while some scholars have studied the impact of change in positive and negative affects on the change in social effort-reward imbalance [96,97,98], this study is aimed at the impact of change in social effort-reward imbalance on change in positive and negative affects, which is a supplement to previous studies. Furthermore, this study puts forward a new proposed path to encourage managers to adjust personal affects through social effort-reward imbalance.

Fourth, life satisfaction has become an important research field [18,19,20] and improving life satisfaction is in line with the UN’s third sustainable development goal (sustainable development goal 3) [99], which can also improve sustainable employability. More and more scholars have begun to explore the related factors affecting life satisfaction and some have pointed out that effort-reward imbalance in the workplace is closely related to reduced life satisfaction [100]. In our study, according to the above content description and model results, we found that positive and negative affect completely mediated the relationship between social effort-reward imbalance and life satisfaction. This result is similar to previous research which found that affects completely mediate the relationship between other psychological factors and life satisfaction [19]. This highlighted that our research results are reliable and have theoretical and practical significance. In our study, positive affect and negative affect exist at the same time. On one hand, exploring the role of positive affect is helpful to study the influence mechanism of effort-reward imbalance and enrich the research content; on the other hand, positive affect as a source of information can promote the improvement of life satisfaction, which in turn can promote the aging workforces’ sustainable employability and provide useful information. Our study may encourage seniors in the workplace to learn more about different factors affecting life satisfaction, so as to better use specific strategies to reduce negative affect and increase positive affect to help improve personal life satisfaction. The results are also a supplement to previous research in the life research field.

Finally, we used a longitudinal method to explore the causal relationship of each variable in the research model. A longitudinal design better assesses the causal relationship between the two variables and minimizes risk of reverse causation [91], making the conclusion more stable and reliable, which is the added value of the study. Based on the conclusions of our study, we can provide some specific recommendations for improving sustainable employability of aging workforces, so as to achieve the primary objective. First, in addition to the distribution according to work, it is also necessary to allow aging workforces to participate in the income distribution with production factors such as technology and management, appropriately raise their salary level. Furthermore, managers should provide aging workforces posts with better working conditions and environment and less mobility, so as to decrease their effort-reward imbalance. Second, they should respect aging workforces’ subjective willingness to work direction, mobilize and arouse their enthusiasm and creativity, and enhance their sense of belonging to the enterprise, so as to increase positive affect and decrease negative affect. Last, aging workforces should enjoy the benefits brought by the enterprise, get recognition and care, so as to improve life satisfaction. Meanwhile, they should actively seek employment/reemployment information in life, recognize their abilities, and keep optimistic about life and sustainable employability at all times.

5.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Reseach

Despite the fact that our study extends the literature and provides some suggestions for improving aging workforces’ sustainable employability, it still has several limitations, and thus, we have put forward some recommendations for future study. Firstly, there may be other variables, such as personality traits, that affect life satisfaction, and it is suggested that future studies consider as many other variables as possible. Secondly, regarding the data collected in our study, social effort-reward imbalance was not measured after 2012; the tracking time was relatively short and only examined two waves of collected data. Consequently, future studies should extend the fixed number of years of the track to further enhance the reliability of the research conclusions. Thirdly, the research object of this study was the aging workforce in the United States and may not have high universality in terms of research conclusion extension, especially for some developing countries. In the future, research can consider collecting data from more countries with the aim of improving global life satisfaction, so as to achieve the UN’s sustainable development goals.

5.3. Conclusions

Improving life satisfaction is consistent with the United Nations sustainable development goals, and has significant meanings with aging workforces’ sustainable employability. This study explored the influencing mechanism of social effort-reward imbalance on life satisfaction, and indicated the positive and negative affect’s mediation effect by using longitudinal data. Improvements in positive affect and decreases in negative affect of aging workforces can improve their life satisfaction by reducing effort-reward imbalance, which is conducive to aging workforces’ sustainable employability.

Author Contributions

X.L. and Y.G. collected and sorted out relevant literature, then conceived and designed the research model of this study. X.L. and Y.G. made contributions to data collection, statistical analysis, results report, and revision of the manuscript. X.L. and Y.G. wrote the paper. Both authors examined the manuscript, provided significant feedback, and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Funding of China (grant no. 71804009, 71974011, 91746116, 71704011, 71972012, 71603018, 71471017, 71601020), Special Fund for Joint Development Program of Beijing Municipal Commission of Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Longitudinal data were collected from the 2008 and 2012 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is widely recognized as the best source of publicly available data on the aging population of the United States. HRS was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration of the United States, and was conducted by the University of Michigan, U.S. Additional details regarding the design of the HRS are available online: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu (accessed on 10 December 2021).

Acknowledgments

Thanks for both authors’ efforts in data collection, data analysis, and paper writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen Van, H.; Dinh Le, M.; Nguyen Van, T.; Nguyen Ngoc, D.; Tran Thi Ngoc, A.; Nguyen The, P. A systematic review of effort-reward imbalance among health workers. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e674–e695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Yang, W.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Siegrist, J. Effort-reward imbalance at school and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: The role of family socioeconomic status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6085–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.U.; Seneviratne, R.D.A. Perceived job stress and presence of hypertension among administrative officers in sri lanka. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2016, 28, 41S–52S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Brauchli, R.; Bauer, G.F. Effort-reward and work-life imbalance, general stress and burnout among employees of a large public hospital in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlander, J.; Weigl, M.; Petru, R.; Angerer, P.; Radon, K. Working conditions and effort-reward imbalance of German physicians in Sweden respective Germany: A comparative study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, K.; Hirao, T.; Yoda, T.; Yoshioka, A.; Shirakami, G. Effort-reward imbalance and low back pain among eldercare workers in nursing homes: A cross-sectional study in kagawa prefecture, Japan. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goal 8. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg8 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Jing, Q.; Bin, W.; Zhuo, H.; Baihe, S. Ethical leadership, leader-member exchange and feedback seeking: A double-moderated mediation model of emotional intelligence and work-unit structure. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fleuren, B.P.I.; Grip, A.D.; Jansen, N.W.H.; Kant, I.; Zijlstra, F.R.H. Unshrouding the sphere from the clouds: Towards a comprehensive conceptual framework for sustainable employability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabius, R.; Thayer, R.D.; Konicki, D.L.; Yarborough, C.M.; Peterson, K.W.; Isaac, F.; Loeppke, R.R.; Eisenberg, B.S.; Dreger, M. The link between workforce health and safety and the health of the bottom line: Tracking market performance of companies that nurture a “culture of health”. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Tough, H.; Brinkhof, M.W.G.; Fekete, C.; Group, S.S. Failed reciprocity in social exchange and wellbeing: Evidence from a longitudinal dyadic study in the disability setting. Psychol. Health 2012, 35, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Sakata, Y.; Theriault, G.; Aratake, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Tsutsumi, A.; Tanaka, K.; Aizawa, Y. Effort–reward imbalance and social support are associated with chronic fatigue among medical residents in Japan. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2008, 81, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, P.; Schablon, A.; Latza, U.; Nienhaus, A. Musculoskeletal pain and effort-reward imbalance—A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N. A review of empirical studies on the model of effort-reward imbalance at work: Reducing occupational stress by implementing a new theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, R.; Siegrist, J. Chronic work stress, sickness absence, and hypertension in middle managers: General or specific sociological explanations? Soc. Ence Med. 1997, 45, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Killmer, C.H.; Siegrist, J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Shi, M.; Yi, F. Mediating effects of affect and loneliness on the relationship between core self-evaluation and life satisfaction among two groups of chinese adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R.W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, S.P. Meditation program mitigates loneliness and promotes wellbeing, life satisfaction and contentment among retired older adults: A two-year follow-up study in four south asian cities. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 25, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, A.; Ng, E.; Lai, S.; Tsien, T.; Busch, H.; Hofer, J.; Lam, C.; Wu, W. Goals and Life Satisfaction of Hong Kong Chinese Older Adults. Clin. Gerontol. 2015, 38, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. 2002. Available online: http://www.who.int/hpr/ageing/ActiveAgeingPolicyFrame.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Carstensen, L.L. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, O. A matter of combination? The influence of work-family life courses on life satisfaction at higher ages among german women. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 42, 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialowolski, P.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D. Longitudinal evidence for reciprocal effects between life satisfaction and job satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G. Relationship between life satisfaction and postretirement employment among older women. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2001, 52, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethics Resource Center. The State of Ethics in Large Companies; The Ethics & Compliance Initiative: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://ethics.org/ecihome/research/nbes/nbes-reports/large-companies (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Institute of Business Ethics. Ethics at Work, 2015 Survey of Employees; Institute of Business Ethics: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.ibe.org.uk/list-of-publications/67/47 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Knesebeck, O.V.D.; Siegrist, J. Reported nonreciprocity of social exchange and depressive symptoms: Extending the model of effort-reward imbalance beyond work. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 55, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F. Work and the Nature of Man; World Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.; Cohen, S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppens, P.; Realo, A.; Diener, E. The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. J Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Feelings and Phenomenal Experiences. Soc. Psychol. Handb. Basic Princ. 2007, 2, 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Kehner, D.; Locke, K.D.; Aurain, P.C. The influence of attributions on the relevance of negative feelings to personal satisfaction. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridja, N. The laws of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1988, 43, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J.; Wege, N.; Pühlhofer, F.; Wahrendorf, M. A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effort-reward imbalance. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlén, G.; Knutsson, A.; Peter, R.; Åkerstedt, T.; Nordin, M.; Alfredsson, L.; Westerholm, P. Effort-reward imbalance, sleep disturbances and fatigue. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 79, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, A.; Kawanami, S.; Horie, S. Effort-reward imbalance and depression among private practice physicians. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2012, 85, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Damkrger, A.; Heins, C.; Wehlitz, L.; Lhr, M.; Driessen, M.; Behrens, J.; Wingenfeld, K. Effort–reward imbalance and burnout among german nurses in medical compared with psychiatric hospital settings. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Oishi, S. Recent findings on subjective well-being. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Warfel, B.L. Urbannism and life satisfaction among the aged. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, K.S.; Martin, H.W. A causal model of life satisfaction among the elderly. J. Gerontol. 1979, 34, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griep, R.H.; Rotenberg, L.; Vasconcellos, A.; Landsbergis, P.; Comaru, C.M.; Alves, M. The psychometric properties of demand-control and effort–reward imbalance scales among brazilian nurses. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.F.; Barrera, M.; Okun, M.A.; Bryant, W.H.M.; Pool, G.J.; Snow-Turek, A.L. The factor structure of received social support: Dimensionality and the prediction of depression and life satisfaction. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 16, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Yao, W.A.; Yan, Z.B.; Gmst, C.; Pei, J.; Wang, H. Impact of effort reward imbalance at work on suicidal ideation in ten european countries: The role of depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastame, M.C. Life Satisfaction in Late Adult Span: The Contribution of Family Relationships, Health Self-Perception and Physical Activity. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40520-020-01658-1 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Fekete, C.; Wahrendorf, M.; Reinhardt, J.D.; Post, M.; Siegrist, J. Work stress and quality of life in persons with disabilities from four european countries: The case of spinal cord injury. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsade, S.G.; Gibson, D.E. Group affect: Its influence on individual and group outcomes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Weiss, H.M. Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravyts, S.G.; Dzierzewski, J.M.; Raldiris, T.; Perez, E. Sleep and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain in mid- to late-life: The influence of negative and positive affect. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 28, e12807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthaud-Day, M.L.; Rode, J.C.; Mooney, C.H.; Near, J.P. The subjective well-being construct: A test of its convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Shumway, T. Good day sunshine: Stock returns and the weather. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1009–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollnow, O.F. The experience of space. Z Gesamte Inn. Med. 1956, 11, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thundiyil, T.G.; Chiaburu, D.S.; Li, N.; Wagner, D.T. Joint effects of creative self-efficacy, positive and negative affect on creative performance. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2016, 10, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Loughren, E.A.; Kinnafick, F.E.; Taylor, I.M.; Duda, J.L.; Fox, K.R. Changes in work affect in response to lunchtime walking in previously physically inactive employees: A randomized trial. Scand. J. Med. Sports 2016, 25, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrona, T.; López-Pérez, B. A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between positive and negative affect and health. Psychology 2014, 5, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fiori, M.; Bollmann, G.; Rossier, J. Exploring the path through which career adaptability increases job satisfaction and lowers job stress: The role of affect. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, Y.; Shi, H.; Gao, Y.; Yang, T. Effect of discrimination on presenteeism among aging workers in the united states: Moderated mediation effect of positive and negative affect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, K.S.; Wang, M. Psychological perspectives on the changing nature of retirement. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldo, B.J.; Hurd, M.D.; Rodgers, W.L.; Wallace, R.B. Asset and health dynamics among the oldest old: An overview of the ahead study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Soc. 1997, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrendorf, M.; Knesebeck, O.V.D.; Siegrist, J. Social productivity and well-being of older people: Baseline results from the share study. Eur. J. Agng 2006, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Pasupathi, M.; Mayr, U.; Nesselroade, J.R. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Edwards, L.M.; Bergeman, C.S. Hope as a source of resilience in later adulthood. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Y.T.; Tolpekin, V.A.; Stein, A. Application of the expectation maximization algorithm to estimate missing values in gaussian bayesian network modeling for forest growth. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Y. Occupational interactions and income level: A social capital study using the first-order difference method. J. Chin. Sociol. 2017, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. An update and extension to sem guidelines for administrative and social science research. Mis. Q. 2011, 35, III–XII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Technometrics 2004, 47, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Leguina, A. Structural equation modeling. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Mackinnon, D.P. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiplinary J. 2008, 15, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, R. Specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 100, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreskog, K.; Sorbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling; Scientific Software International Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S. Predicting residents’ pro-environmental behaviors at tourist sites: The role of awareness of disaster’s consequences, values, and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Franěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Qiu, H.L.; Wu, X.F. Tourist destination image, place attachment and tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: A case of Zhejiang tourist resorts. Tour. Trib. 2014, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Lu, S.J.; Zhang, H.L. On environmental attitudes and behavior intention of tourists in natural heritage site: A case study of Jiuzhaigou. Tour. Trib. 2009, 24, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Hou, P. Investigation and research on willingness of citizen’s environmental behavior in Beijing. China Population. Resour. Environ. 2010, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, D.W.; Jones, M.C.; Kathryn, C.; Mccann, S.K.; Lorna, M.K. Stress in nurses: Stress-related affect and its determinants examined over the nursing day. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Anusic, I.; Yap, S.C.Y.; Lucas, R.E. Does personality moderate reaction and adaptation to major life events? Analysis of life satisfaction and affect in an Australian national sample. J. Res. Pers. 2014, 51, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busseri, M.A. Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 122, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Tsukayama, E.; Kashdan, T.B. Examining the effect of affect on life satisfaction judgments: A within-person perspective. J. Res. Personal. 2017, 68, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Larsen, R.J. Research on Life Satisfaction of Children and Youth: Implications for the Delivery of School-Related Services. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-00541-018 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Garcia, D.; Moradi, S. The affective temperaments and well-being: Swedish and iranian adolescents’ life satisfaction and psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koydemir, S.; Ömer, F.; Schütz, A. Differences in how trait emotional intelligence predicts life satisfaction: The role of affect balance versus social support in india and germany. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Huang, X.; Chen, M.; Rui, G.; Du, C. Life satisfaction among chinese drug addicts: The role of affect and social support. J. Drug Issues 2019, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, L.B.; Christensen, J.O.; Knardahl, S. Psychological and Social Work Factors as Predictors of Mental Distress and Positive Affect: A Prospective, Multilevel Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, S.; Brosschot, J.F.; Rien, V.; Thayer, J.F. Cardiac effects of momentary assessed worry episodes and stressful events. Psychosom. Med. 2007, 69, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, A.; Mets, T.; Martinmki, K.; Mauno, S.; Kinnunen, U.; Rusko, H. Heart rate variability related to effort at work. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, R.; Herrmann, C.; Ludyga, S.; Colledge, F.; Brand, S.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M. Does Cardiorespiratory Fitness Buffer Stress Reactivity and Stress Recovery in Police Officers? A Real-Life Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Development Goal 3. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Chandola, T.; Marmot, M.; Siegrist, J. Failed reciprocity in close social relationships and health: Findings from the whitehall ii study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).