Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention among Foreigners in Kazakhstan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Context of This Study

1.2. Problem Statement and Purpose of This Study

1.3. Approach to and Objectives of This Study

- (1)

- To explore the miscellaneous factors, theories, and models that explain EI.

- (2)

- To develop and examine a research model containing the role of GS and other factors influencing EI among foreigners in Kazakhstan.

- (3)

- To provide insights into improving (foreign) entrepreneurship and suggestions on further research for academics, researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Approaches to EI Research in General

2.2. Approach to EI Research in This Study

2.3. Application of the TPB Model in EI Research

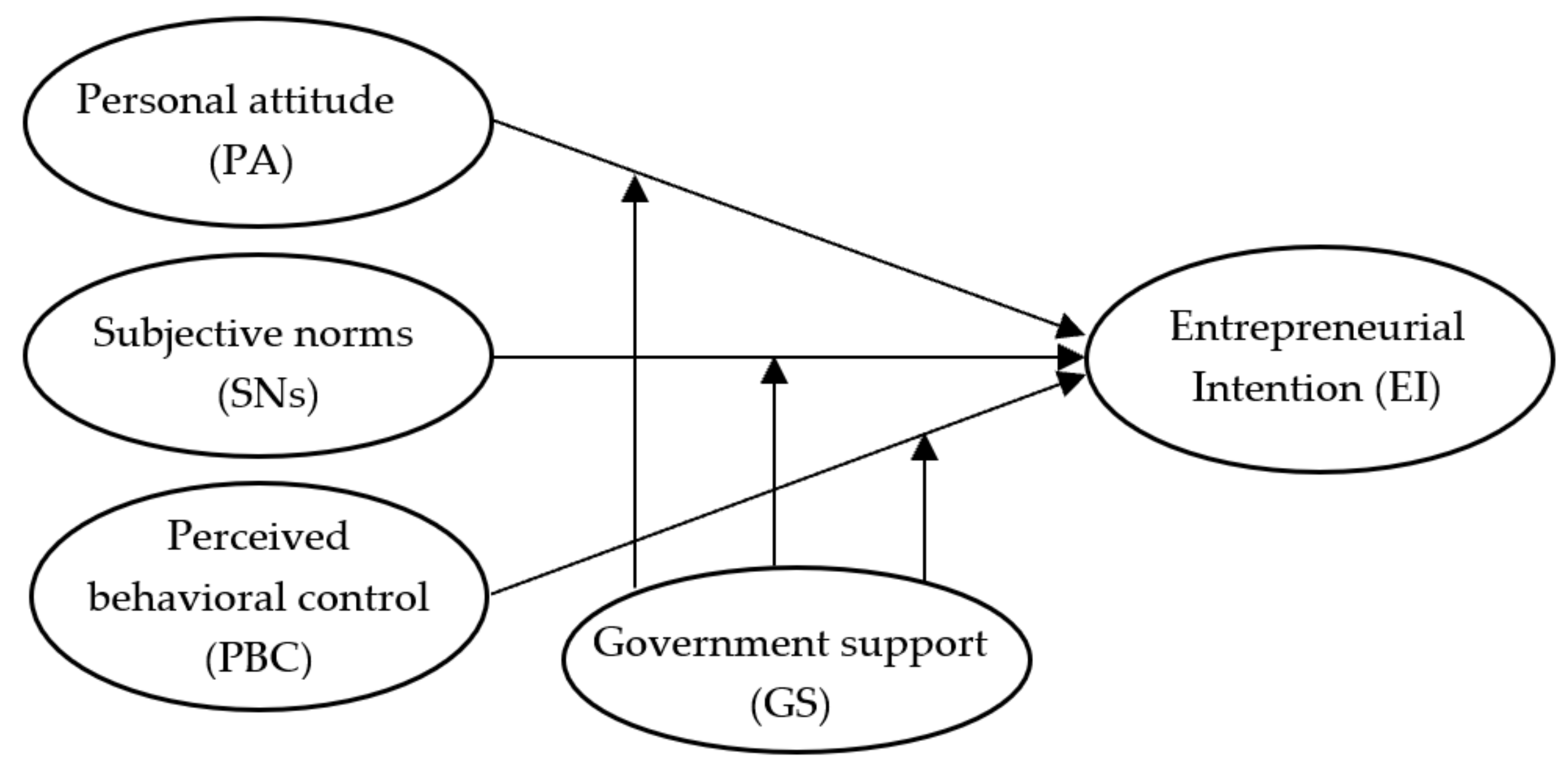

3. Hypothesis Development and Research Framework

3.1. Personal Attitude (PA) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI)

3.2. Subjective Norms (SNs) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI)

3.3. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI)

3.4. Effects of Government Support (GS)

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Examination

4.2.1. Missing Data Analysis

4.2.2. Detection of Outliers

4.2.3. Tests of Assumptions

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results and Findings

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

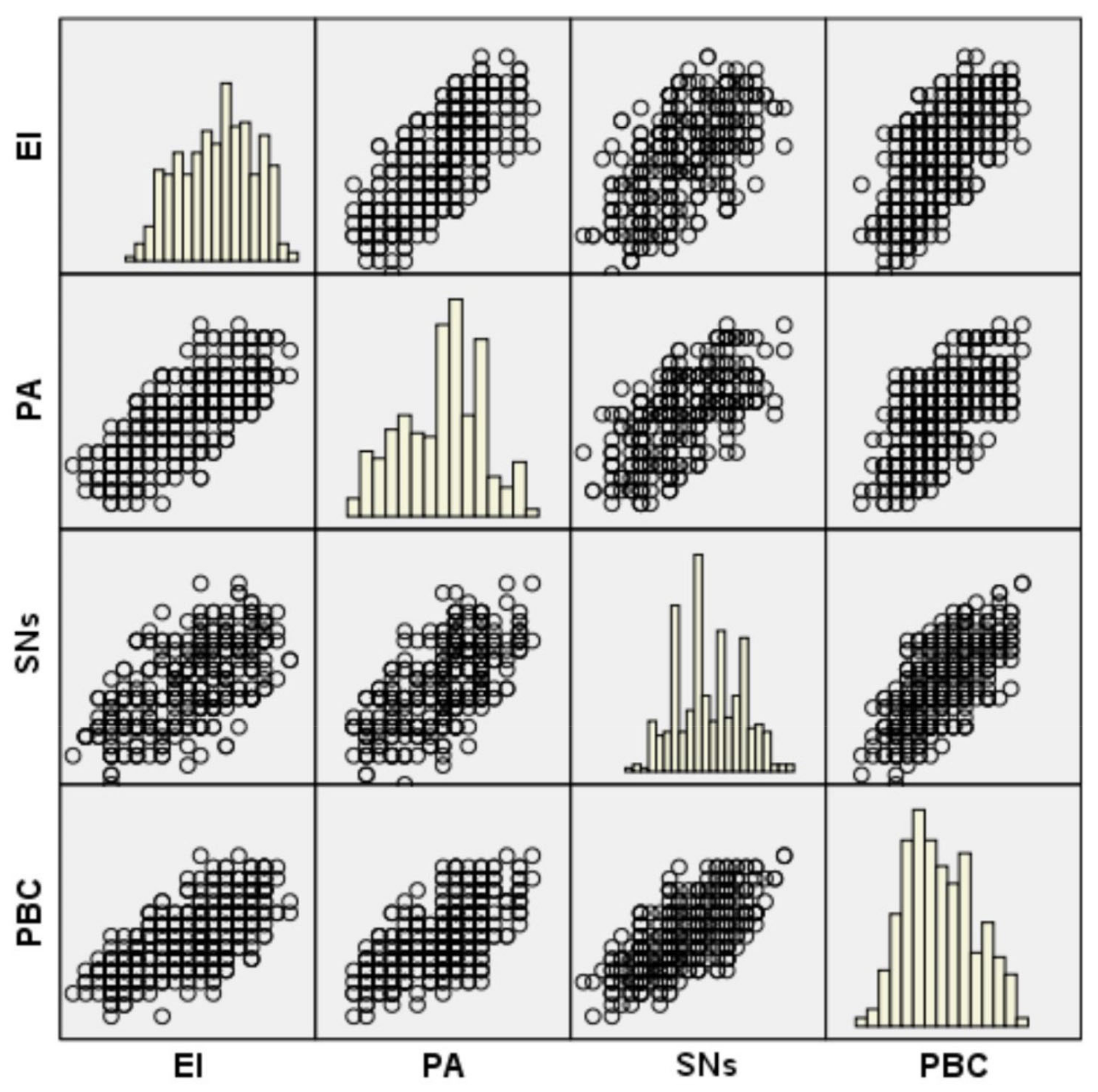

5.2. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

5.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

5.3.1. Assessing the Overall Model Fit

5.3.2. Assessing the Variables’ Importance

5.3.3. Identifying Multicollinearity

5.3.4. Examining Correlations

5.3.5. Validating the Results

5.3.6. Validation of the Hypotheses

- (1)

- Personal attitude (PA) toward entrepreneurial behavior positively influences entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan.

- (2)

- Subjective norms (SNs) insignificantly influence entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan.

- (3)

- Perceived behavioral control (PBC) positively influences entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan.

- (4)

- With the moderation of government support (GS), the relationship between personal attitude (PA) toward entrepreneurial behavior and entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan strengthens.

- (5)

- With the moderation of government support (GS), the relationship between subjective norms (SNs) and entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan is insignificant.

- (6)

- With the moderation of government support (GS), the relationship between perceived behavioral control (PBC) and entrepreneurial intention (EI) among foreigners in Kazakhstan strengthens.

6. Discussions

- (1)

- The target population or the sample itself is too broad, with the cultural or contextual variety of 60 countries. Hence, either normative beliefs that are too divergent or heterogeneous compliance with beliefs formed among the foreigners. In other words, a uniform pattern of SNs was unable to be formulated to influence their EI.

- (2)

- The impact of SNs on the foreigners weakly facilitates overseas entrepreneurship in comparison with their PA and PBC.

- (3)

- The role of GS may not impact upon the opinions of important others or the entrepreneur’s reaction to these opinions. GS functions mainly to motivate the entrepreneur’s PA and PBC toward his/her business start-up.

- (4)

- The perceived level of GS in Kazakhstan is relatively low, which limited its interaction effect with SNs.

- (5)

- The high uncertainty and risks incurred by the outbreak of COVID-19 might change the general opinions about self-employment, to say nothing of going abroad to create ventures, especially for the new entrepreneurs in this survey.

7. Implications for Academics, Entrepreneurs, and Politicians

8. Conclusions

8.1. Major Contributions of This Study

8.2. Limitations of This Study

8.3. Recommendations for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baron, R.A. Entrepreneurship: A Process Perspective, 2nd ed.; Inglés; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Creative Response in Economic History. J. Econ. History 1947, 7, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoselitz, B.F. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Amer. J. Econ. Sociol. 1952, 12, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayyagari, M.; Demerguc-Kunt, A.; Beck, T. Small and Medium Enterprises across the Globe: A New Database. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3127; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J.E. Entrepreneurial Strategy for the Economic Development of the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: A Study of Selected Projects/Organizations in the Region. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.A.C.; Davey, T. Attitudes of Higher Education Students to New Venture Creation: A Preliminary Approach to the Portuguese Case. Lusa, 18 June 2008. Ind. Higher Educ. 2010, 24, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): Luxembourg 2017/2018; STATEC: Luxembourg, 2019.

- World Bank. The Global Economic Outlook During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Changed World. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Kazinform. Available online: https://www.inform.kz/cn/kazakhstani-smes-manufactured-products-worth-kzt12-7trn-in-h1-2019_a3579744/amp (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): Kazakhstan 2016/2017; Graduate School of Business (GSB) of Nazarbaeyev University: Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan; JSC “Economic Research Institute” (ERI): Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, 2017.

- German, N.K. Formation and Development of Ethnic entrepreneurship of Koryo Saram in Kazakhstan. Int. Area Rev. 2009, 12, 127–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kazinform. How Many Foreigners Are Working in Kazakhstan? Available online: https://www.inform.kz/ru/skol-ko-inostrancev-rabotaet-v-kazahstane_a3604851 (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Doing Business in Kazakhstan, 2018, 2019. Available online: www.bakermeckenzie.com (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Export-Enterprises. Kazakhstan: Economic and Political Overview. Available online: https://www.nordeatrade.com/en/explore-new-market/kazakhstan/economical-context (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- UNCTAD. Available online: https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/countries/107/kazakhstan (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Freedom House. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/country/kazakhstan/freedom-world/2020 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- World Bank. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Kazakhstan/wb_political_political_stability/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/home (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/kazakhstan-population/ (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- LIF. Available online: https://www.prosperity.com/globe/kazakhstan (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- WEF. Available online: https://www.qazaqtimes.com/en/article/64870 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- The Astana Times. Available online: https://astanatimes.com/2019/10/kazakhstan-ranks-55th-in-global-competitiveness-index-moves-up-four-spots/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- GII. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Kazakhstan/GII_Index/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- USNEWS. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/kazakhstan (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- EPI. Available online: https://epi.envirocenter.yale.edu/epi-country-report/KAZ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- The Kazakh Times. Available online: https://qazaqtimes.com/en/article/64870 (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- WJP. Available online: https://qazaqtimes.com/en/article/64870 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- World Bank. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Global Entrepreneurship Index (GEI) (2018, 2019); The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute (GEDI): Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- The Astana Times. Available online: https://astanatimes.com/2018/10/foreign-investments-in-kazakhstan-grow-15-4-percent-in-six-months-exceed-12-billion/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- World Investment Report (WIR); United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCAD): New York, NY, USA; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Export-Enterprises. Kazakhstan: Foreign Investment. Available online: https://santandertrade.com/en/portal/establish-overseas/kazakhstan/investing (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Syriopoulos, K. The Impact of COVID-19 on Entrepreneurship and SMES. J. Int. Acad. Case Stud. 2020, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cuyper, L.D.; Kucukkeles, B.; Reuben, R. Discovering the Real Impact of COVID-19 on Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/how-covid-19-will-change-entrepreneurial-business (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- McCarthy, B. Strategy is Personality-driven, Strategy is Crisis-driven: Insights from Entrepreneurial Firms. Manage. Dec. 2003, 41, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP in Kazakhstan. UNDP Supports Kazakhstan during the Novel COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.kz.undp.org/content/kazakhstan/en/home/presscenter/news/2020/april/undp-supports-kazakhstan-during-the-novel-covid-19-pandem (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Anna, M.S. Environmental Factors that Affect the Entrepreneurial Intention. Master’s Thesis, UAB—Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 26 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, S.; Kim, B. Government Support for SME Innovations in the Regional Industries: The Case of Government Financial Support Program in South Korea. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsden, A.H. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.J.; Jiang, C.; Shenkar, O. The Quality of Local Government and Firm Performance: The Case of China’s Provinces. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 11, 679–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D.J.; Tether, B.S. Public Policy Measures to Support New Technology-based Frms in the European Union. Res. Policy 1998, 26, 1037–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrul, A.; Patrick, L.K.C. Critical Issues of Starting Entrepreneurship in Kazakhstan. IUP J. Entrep. Dev. 2006, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnzylber, P.; Maloney, W.F.; Montes-Rojas, G.V. Releasing Constraints to Growth or Pushing on a String? Policies and Performance of Mexican Micro-firms. J. Dev. Stud. 2009, 45, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxat, K. E-Government in Kazakhstan: A Case Study of Multidimensional Phenomena; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNPAN. The Global E-Government Survey. E-Government for the Future We Want. Available online: http://unpan3.un.org/egovkb/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2014 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Alima, D. Dynamics of Entrepreneurship Development in Kazakhstan. J. Market. Dev. Comp. 2012, 6, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Moigan Lewis. Economic Stabilization and Business Support in Kazakhstan During COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/economic-stabilization-and-business-support-in-kazakhstan-during-covid-19-cv19-lf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM): Kazakhstan 2018/2019; Graduate School of Business (GSB) of Nazarbaeyev University: Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, 2019.

- Elena, P.; Nurlan, I.; Oleg, M.; Tatyana, K. Ecosystem of Entrepreneurship: Risks Related to Loss of Trust in Stability of Economic Environment in Kazakhstan. Entrep. Sustain. Iss. 2017, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, B.J.; Jellinek, M. The Operation of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1989, 13, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasti, Z.; Pasvishe, F.A.; Motavaseli, M. Normative Institutional Factors Affecting Entrepreneurial Intention in Iranian Information Technology Sector. J. Manag. Strat. 2012, 3, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Nabi, G.; Krueger, N. British and Spanish Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Comparative Study. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2013, 33, 73–103. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Lu, G.; Kang, H. Entrepreneurial Intentions and its Influencing Factors: A Survey of the University Students in Xi’an China. Creat. Educ. 2012, 3, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.D.; Peters, P.M. Entrepreneurship, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, R.; Coulton, G.; Chick, A.B.A.; Mellor, N.; Fisher, A. Entrepreneurship for Everyone; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organiz. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, C.L.; Priem, R.L.; McGee, J.E. Venture Creation and the Enterprising Individual: A Review and Synthesis. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.B. “Who is an Entrepreneur?” Is the Wrong Question. Am. J. Small Bus. 1988, 12, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krueger, N.F.; Carsrud, A.L. Entrepreneurial Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior. Entrep. Regional Dev. 1993, 5, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, D.; Selçuk, S.S. Which Factors Affect Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students? J. Europ. Indust. Train. 2008, 33, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, B.; Levine, P. A Behavioral Model of Entrepreneurial Supply. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1986, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, N.; Lüthje, C. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students-A Benchmarking Study. Int. J. Innov. Tech. Manag. 2004, 1, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, P.B.; Stimpson, D.V.; Huefner, J.C.; Hunt, H.K. An Attitude Approach to the Prediction of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, D.; Bryson, J.; Wood, P. The Rise and Fall of Small Service Firms in the United Kingdom. Int. Small Bus. J. 1992, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, M.; Scott, D. Why Women Enter into Entrepreneurship: An Explanatory Model. Women Manag. Rev. 2001, 16, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N. The Five Stages of the Entrepreneur; Venture: Champaign, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R.D. The woman entrepreneur: Characteristics, skills, problems and prescriptions for success. In The Art and Science of Entrepreneurship; Ballinger: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, C.H.; Moser, S.B. A Longitudinal Investigation of the Impact of Family Background and Gender on Interest in Small Firm Ownership. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1996, 34, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.K.; Wong, P. Entrepreneurial Interest of University Students in Singapore. Technovation 2004, 24, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Virick, M. Assessing Entrepreneurial Intentions amongst Students: A Comparative Study in National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance; National Collegiate Inventors and Innovators Alliance: Hadley, MA, USA, 2008; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Nizam, Z.M.; Rozaini, M.R.M. Assessing “ME Generation’s” Entrepreneurship Degree Programmes in Malaysia. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su´arez-´Alvarez, J.; Pedrosa, I. The Assessment of Entrepreneurial Personality: The Current Situation and Future Directions. Pap. Psićologo 2016, 37, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. Entrepreneurial behavior and characteristics of entrepreneurs. In The Achieving Society; McClelland, D.C., Ed.; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, N.; Gomathi, S. The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Startup Intention. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus, R.H. Risk Taking Propensity of Entrepreneurs. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 509–520. [Google Scholar]

- Athayde, R. Measuring Enterprise Potential in Young People. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terek, E.; Nikolić, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Božić, S.; Nastasić, A. Enterprise Potential, Entrepreneurial Intentions and Envy. Centr. Europ. Bus. Rev. 2017, 6, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caird, S. Testing Enterprise Tendency in Occupational Groups. Brit. J. Manag. 1991, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized Expectations for Internal versus External Control of Reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thu, T.D.T.; Hieu, H.L. Building up the Entrepreneurial Intent Construct among Technical Students in Vietnam. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2017, 5, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, N. Entrepreneurial Intention: Antecedents to Entrepreneurial Behavior in the U.S.A and Turkey. J. Global Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brockhaus, R.H. Entrepreneurial Folklore. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1987, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lüthje, C.; Franke, N. The Making of an Entrepreneur: Testing a Model of Entrepreneurial Intent among Engineering Students at MIT. R&D Manag. 2003, 33, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.H.; Hong, D. Entrepreneurial Spirit among East Asian Chinese. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 42, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s Put the Person Back into Entrepreneurship Research. Europ. J. Work Organiz. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.G.; Twomey, D.F. The Long-term Supply of Entrepreneurs: Students' Career Aspirations in Relation to Entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1988, 26, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Wong, P.K. An Exploratory Study of Technopreneurial Intentions: A Career Anchor Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeger, M.; Sušanj, Z.; Mijoč, J. Entrepreneurial Intention Modeling Using Hierarchical Multiple Regression. Croatian Operat. Res. Rev. 2014, 5, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Traits, and Actions: Dispositional Prediction of Behavior in Personality and Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 20, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The Influence of Self-efficacy on the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, M.E.; Ekeberg, S.E. The Role of Intentions in Work Motivation: Implications for Goal-setting Theory and Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 14, 361–384. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F. The Impact of Prior Entrepreneurial Exposure on Perceptions of New Venture Feasibility and Desirability. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1993, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfving, J.; Brännback, M.; Carsrud, A. Towards a Contextual Model of Entrepreneurial Intentions. In Understanding the Entrepreneurial Mind; Carsrud, A.L., Brännback, M., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, M.; Mcgee, G.; Cavender, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationships between Individual Job Satisfaction and Individual Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, F.; Xiao, S. Work Values, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in China. Int. J. Human Res. Manag. 2012, 23, 2144–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruffman, T.; Ward, M. Entrepreneurial Intention: The Awakening of New Businesses; Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå Universitet: Umeå, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyat, C.; Julien, P. Defining the Field of Research in Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Morse, E.; Seawright, K.; Smith, B. Cross-cultural Cognitions and the Venture Creation Decision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 974–993. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Smith, J.B.; Morse, E.A.; Seawright, K.W.; Peredo, A.M.; McKenzie, B. Are Entrepreneurial Cognitions Universal?Assessing Entrepreneurial Cognitions across Cultures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Lau, C.M. A Cross-cultural Cognitive Model of New Venture Creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 20, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Wright, M.; Ucbasaran, D. Information Search and Opportunity Identification: The Importance of Prior Business Ownership Experience. Int. Small Bus. J. 2009, 27, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Cools, E.; Van den Broeck, H.; Vanderheyden, K. In Search for the Heffalump: An Exploration of the Cognitive Style Profiles among Entrepreneurs. J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 2005, 10, 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, S.; O’Neil, K.; Cromie, S. Understanding Enterprise, Entrepreneurship and Small Business; Estados Unidos, Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, C.W.; Chell, E.; Hayes, J. Intuition and Entrepreneurial Behavior. Eur. J. Work Organiz. Psychol. 2000, 9, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneman, D.; Tversky, A. Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.A.; Markman, G.D. Cognitive Mechanisms: Potential Differences between Entrepreneurs and Non-entrepreneurs. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research; Reynolds, P.D., Bygrave, W.D., Eds.; Babson College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R.L.; Dimitriadi, N.; Gavidia, J.V.; Schlaegel, C.; Delanoe, S.; Alvarado, I.; He, X.; Buame, S.; Wolff, B. Entrepreneurial Intent: A Twelve-country Evaluation of Ajzen’s Model of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions; The RENT IX Workshop: Piacenza, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Seelig, T. InGenius: A Crash Course on Creativity; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S.E. The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, J. The Curious Perils of Seeing the Other Side. Scient. Amer. Mind 2012, 23, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Fox, J. Contact with Nature. In Making Healthy Places: Designing and Building for Health, Well-being, and Sustainability; Dannenberg, A., Frumkin, H., Jackson, R.R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vesper, K.H. New Venture Strategies; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship. In The Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus, R.H.; Nord, W.R. An Exploration of Factors Affecting the Entrepreneurial Decision: Personal Characteristic vs. Environmental Conditions; Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management Proceedings: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 1979; Available online: https://journals.aom.org/doi/pdf/10.5465/ambpp.1979.4977621 (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Socio-cultural Factors and Transnational Entrepreneurship: A Multiple Case Study in Spain. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F.; Davidsson, P. Where do They Come From? Prevalence and Characteristics of Nascent Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2000, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eby, L.T. Mentorship. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 505–525. [Google Scholar]

- Clutterbuck, D. Everyone Needs a Mentor: Fostering Talent in Your Organization, 4th ed.; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Modern Mentoring: Ancient Lessons for Today. Music Educ. J. 2005, 92, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Intention-based Models of Entrepreneurship Education. Piccolla Impresa 2004, 3, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; DeTienne, D.R. Prior Knowledge, Potential Financial Reward, and Opportunity Identification. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firms Emergence and Growth; Katz, J., Brockhaus, R., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1997; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno, J.; Folta, T.; Cooper, A.; Woo, C. Survival of the Fittest? Entrepreneurial Human Capital and the Persistence of Underperforming Firms. Admin. Science Quart. 1997, 42, 750–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Chang, D.; Lim, S.B. Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: A Comparative Study of the U. S. and Korea. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jorge-Moreno, J.; Castillo, L.L.; Triguero, M.S. The Effect of Business and Economics Education Programs on Student’s Entrepreneurial Intention. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2012, 36, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrepreneur. Getting Started with Business Incubators. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/52802 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Clausen, T.; Korneliussen, T. The Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Speed to the Market: The Case of Incubator Firms in Norway. Technovation 2012, 32, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar, K.; Nakata, C. Designing Global New Product Teams: Optimizing the Effects of National Culture on New Product Development. Int. Mark. Rev. 2003, 20, 397–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Corbett, A.C. Proclivity for Improvisation as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.C.; Maat, S.M.; Mohd, N. Identifying Factors that Affecting the Entrepreneurial Intention among Engineering Technology Students. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Wiedenmayer, G. From Traits to Rates: An Ecological Perspective on Organizational Foundings. In Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth; Katz, J.A., Brockhaus, R.H., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1993; pp. 145–195. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N.M.; Gartner, W.B.; Reynolds, P.D. Exploring Start-up Event Sequences. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. How Long Does It Take to Start a Small Business? UK Start-Ups. Available online: https://www.ukstartups.org/how-long-does-it-take-to-start-a-smallbusiness/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Djankov, S.; La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. The Regulation of Entry. Quart. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Grilo, I.; Thurik, A.R. Explaining entrepreneurship and the role of policy: A framework. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fizza, S. Measuring Entrepreneurial Intentions: Role of Perceived Support and Personality Characteristics; Department of Management Sciences, Capital University of Science and Technology: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, V. Why Intellectual Property is Critical for Start-Ups. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/254442 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Carr, C. Using Someone Else’s Intellectual Property Comes at a Price. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/227570 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Shapero, A. The Role of Entrepreneurship in Economic Development at the Lessthan-National Level; The Corporation for Enterprise Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, A.A.; Ritchie, J.R. Understanding the Process of Starting Small Businesses. Europ. Small Bus. J. 1982, 1, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, J.D.; Autio, E. A Theoretical Grounding and Test of the GEM Model. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, K.A.; Krishna, K.V.S.M. Agricultural Entrepreneurship: The Concept and Evidence. J. Entrep. 1994, 3, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. The Motivation to Become an Entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sexton, D.L. Advancing Small Business Research: Utilizing Research from Other Areas. Amer. J. Small Bus. 1987, 11, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A. Self-employment as a Career Choice: Attitudes, Entrepreneurial Intentions, and Utility Maximization. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, A.; Laspita, S.; Panopoulos, A. Entrepreneurial Intention Models and Female Entrepreneurship; Conference in Greece; (GSRT) “Foremost” Project: 3864; Technical University of Crete, University of Crete: Rethymnon, Greece, 2017; Available online: http://foremost.tuc.gr/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/D2-Report_Entrepreneurial-intention-models-and-female-entrepreneurship.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The Future of Research on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A. Beyond Entrepreneurial Intentions: Values and Motivations in Entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, W.R.; Hofer, C.W. Improving New Venture Performance: The Role of Strategy, Industry Structure, and the Entrepreneur. J. Bus. Ventur. 1987, 2, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Prediction of Employment Status Choice Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 21, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornikoski, E.; Maalaoui, A. Critical Reflections—The Theory of Planned Behavior: An Interview with Icek Ajzen with Implications for Entrepreneurship Research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2019, 37, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovleva, T.; Kolvereid, L.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurial Intentions in Developing and Developed Countries. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.W.; Gomez, C. The Relationship among National Institutional Structures, Economic Factors, and Domestic Entrepreneurial Activity: A Multi-country Study. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Brit. J. Social Psych. 2001, 40, 417–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bullough, A.; Renko, M.; Myatt, T. Danger Zone Entrepreneurs: The Importance of Resilience and Self-Efficacy for Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, H.; Klofsten, R.; Parker, G.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial Intent among Students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Testing the Entrepreneurial Intention Model on a Two-Country Sample; Documents de Treball; Departament d’Economia de l’Empresa: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sondari, M.C. Is Entrepreneurship Education Really Needed?: Examining the Antecedent of Entrepreneurial Career Intention. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 115, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Person. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: McGraw-Hill, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Durand, R.M.; Gur-Arie, O. Identification and Analysis of Moderator Variables; Working Paper, No. 249; Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.; Wong, M. Entrepreneurial Intention: Triggers and Barriers to New Venture Creations in Singapore. Singapore Manag. Rev. 2006, 28, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Vanevenhoven, J.; Liguori, E. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: Introducing the Entrepreneurship Education Project. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Miller, C.; Jones, A.; Packham, G.; Pickernell, D.; Zbierowski, P. Attitudes and Motivations of Polish Students towards Entrepreneurial Activity. Educ. Train. 2001, 53, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A Cross-cultural Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Career Dev. 2011, 39, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siu, W.S.; Lo, E.S.C. Cultural Contingency in the Cognitive Model of Entrepreneurial Intention. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Urbano, D.; Guerrero, M. Regional Variations in Entrepreneurial Cognitions: Start-up Intentions of University Students in Spain. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.; Trost, M. Social Influence: Social Norms, Conformity, and Compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D., Fiske, S., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tkachev, A.; Kolvereid, L. Self-employment Intentions among Russian Students. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1999, 11, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, A. The Influence of Perceived Social Norms on Entrepreneurial Intentions; University of Twente: Twente, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Who Wants to be an Entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial Intentions among Saudi University Students. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4029–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek, B.E.N. Explaining the Intent to Start a Business among Saudi Arabian University Students. Int. Rev. Manag. Market. 2016, 6, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise Education: Influencing Students’ Perceptions of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana, J.M.; Aponte, M.; Urbano, D. University Students’ Attitudes towards Entrepreneurship: A Two Countries Comparison. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Social Psychol. 2002, 32, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Sanchez, A.; Baixauli-Soler, S.; Carrasco-Hernandez, A.J. A Missing Link: The Behavioral Mediators between Resources and Entrepreneurial Intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; Leona, S.A.; West, S.H. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mariusz, U.; Adnan, U.H. Are You Environmetally Conscious Enough to Differentiate between Greenwashed and Sustainable Items? A Global Consumers Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A.U.; Nair, S.L.S.; Kucukaltan, B. Management and Administrative Insight for the Universities: High Stress, Low Satisfaction and No Commitment. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solesvik, M.Z.; Westhead, P.; Kolvereid, L.; Matlay, H. Student Intentions to Become Self-employed: The Ukrainian Context. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Daniel, L.G. A Framework for Reporting and Interpreting Internal Consistency Reliability Estimates. Measur. Eval. Counsel. Dev. 2002, 35, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The Assessment of Reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Crano, W.D.; Brewer, M.B. Principles and Methods of Social Research; Allyn & Bacon: Newton, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Test. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Ft Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.O.; Mueller, C.W. Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issue; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.; Lee, H. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Application; Vinzi, V.E., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 645–689. [Google Scholar]

- Komiak, S.Y.X.; Benbasat, I. The Effects of Personalization and Familiarity in Trust and Adoption of Recommendation Agents. MIS Quart. 2006, 30, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.D.; Yu, C.C. Descriptive Statistics for Modern Test Score Distributions: Skewness, Kurtosis, Discreteness, and Ceiling Effects. Educat. Psychol. Meas. 2014, 75, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step. In A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 10th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do Entrepreneurship Programmes Raise Entrepreneurial Intention of Science and Engineering Students? The Effect of Learning, Inspiration and Resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gird, A.; Bagraim, J.J. The Theory of Planned Behavior as Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intent amongst Final-year University Students. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2008, 38, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Kautonen, T.; Fink, M. Regional Social Legitimacy of Entrepreneurship: Implications for Entrepreneurial Intention and Start-up behavior. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahra, S.; Welter, F. Entrepreneurship Education for Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe. In Entrepreneurship and Higher Education; Potter, J., Ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 165–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fiet, J.O. The Pedagogical Side Entrepreneurship Theory. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatyana, T.; Leyla, G.; Nadezhda, S.; Maciej, W.; Sergey, V. An Assessment of Regional Sustainability via the Maturity Level of Entreprenerial Ecosystems. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intent: A Meta-analytic Test and Integration of Competing Models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What do We Still Need to Know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Index | Description | Result | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Freedom | Based on 10 political rights and 15 civil liberties [16] | 22/100 (2019 scores) | Not free |

| Political stability index | Based on 195 countries [17] | 0 (2018 scores) | Politically stable | |

| E | GDP per capita | Based on International Monetary Fund data [18] | 69th/192 (nominal, 2019 rank); 52nd/192 (PPP, 2019 rank) | The largest economy in Central Asia |

| S | Population growth rate | Estimated population is 19.1 million (68% Kazakhs, 19.3% Russians, and others (Uzbeks, Uighurs, etc.)); the growth rate is only 0.89% [19] | 89th/171 (2019 rank) | Low population growth rate |

| Net migration rate | 0.4 migrants/1000 population [19] | 51st/121 (2019 rank) | Low migration rate | |

| Life expectancy | Median age is 31.6 years; life span is 72 years [19] | 85th/138 (2019 rank) | Relatively low life span | |

| Prosperity index | Strong in education and the investment environment [20] | 68th/167 (2019 rank) | Increasingly promising | |

| Global social mobility index | Key indicators are health, education, technology, work, protection, and institutions. Overall index score: 64.8 [21] | 38th/82 (2020 rank) | High capacity for a child to experience a better life than their parents | |

| T | Global competitive index | Drivers of productivity and long-term economic growth reported by the World Economic Forum; a score of 63 points at 103 indicators or 12 pillars [22] | 55th/141 (2019 rank) | Increasingly competitive |

| Global innovation index | Based on innovation capabilities; 80 indicators [23] | 79th/129 (2019 rank) | Increasingly innovative | |

| E | The world’s best countries | Adventure (5.2), citizenship (1.7), cultural influence (0.0), entrepreneurship (0.6), heritage (3.2), movers (26.6), open for business (29.9), power (7.8), and quality of life (4.9) [24] | 66th/80 (2019 rank) | Relatively low among the best countries |

| Environmental performance index | Scores: 54.56/100 [25] | 101st/180 (2018 rank) | Medium environmental performance | |

| Global tourism ranking | Reported by the World Economic Forum [26] | 81st/136 (2018 rank) | Medium tourism ranking | |

| L | Rule of law index | Modernization of the legal framework and adherence to international best practices reported by the World Justice Project [27] | 62nd/128 (2020 rank) | Highest in Central Asia |

| Doing business ranking | Ease of doing business [28] | 22nd/190 (2020 rank) | High ranking | |

| Global entrepreneurship index | [29] | 59th/137 (2019 rank) | Medium entrepreneurial ranking |

| Government Support | Description |

|---|---|

| Educational support |

|

| Cultural support |

|

| Environmental support |

|

| Financial support |

|

| Government policies |

|

| Government programs |

|

| Category | Typical Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors [67,68,69,70,71,72] |

|

|

| Personality or Personal factors [61,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] |

|

|

| Situational factors [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] |

|

|

| Cognitive factors [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108] |

|

|

| Social factors [69,73,83,90,94,98,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130] |

|

|

| Environmental factors [37,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146] |

|

|

| Model | Factors |

|---|---|

| Shapero’s [116] model of entrepreneurial event (SEE) |

|

| Bird’s [51] implementing entrepreneurial ideas model |

|

| Robinson’s et al. [64] entrepreneurial attitude orientation model |

|

| Ajzen’s [57] theory of planned behavior (TPB) model |

|

| Krueger and Carsrud’s [60] intentional basic model |

|

| Krueger and Carsrud’s [60] theory of planned behavior entrepreneurial model |

|

| Krueger and Brazeal’s [149] entrepreneurial potential model |

|

| Boyd and Vozikis’ [92] intention model |

|

| Davidsson’s [110] economic–psychological model |

|

| Douglas and Shepherd’s [150] maximization of expected utility model |

|

| Elfving’s et al. [95] contextual intention model |

|

| Construct | Source of Instruments | Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha * | CR ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI | Liñán and Chen [163] Solesvik et al. [192] | 0.898 | 0.901 |

| PA | Liñán and Chen [163] Solesvik et al. [192] | 0.909 | 0.913 |

| SNs | Liñán and Chen [163] Solesvik et al. [192] | 0.923 | 0.927 |

| PBC | Solesvik et al. [192] Liñán, Urbano, and Guerrero [177] | 0.878 | 0.880 |

| GS | GEM [49] for government policies GEM [49] for government programs | 0.955 | 0.956 |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| EI | (1) I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur. | 0.799 |

| (2) My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur. | 0.751 | |

| (3) I will make every effort to start and run my own firm. | 0.838 | |

| (4) I am determined to create a firm in the future. | 0.749 | |

| (5) I have very seriously thought of starting a firm. | 0.749 | |

| (6) I have the firm intention to start a firm some day. | 0.771 | |

| PA | (1) Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages to me. | 0.819 |

| (2) It is desirable for me to become an entrepreneur. | 0.771 | |

| (3) It is attractive for me to become an entrepreneur. | 0.923 | |

| (4) If I had the opportunity and resources, I would love to start a business. | 0.810 | |

| (5) Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction. | 0.745 | |

| (6) Among various options, I would rather be an entrepreneur. | 0.704 | |

| SNs | (1) My closest family members think that I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur. | 0.784 |

| (2) I do care about what my closest family members think as I decide on whether or not to pursue self-employment. | 0.745 | |

| (3) My closest friends think that I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur. | 0.836 | |

| (4) I do care about what my closest friends think as I decide on whether or not to pursue self-employment. | 0.787 | |

| (5) People that are important to me think I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur. | 0.887 | |

| (6) I do care about what people important to me think as I decide on whether or not to pursue self-employment. | 0.901 | |

| PBC | (1) If I wanted to, I could easily become an entrepreneur. | 0.890 |

| (2) Starting a business and keeping it viable would be easy for me. | 0.766 | |

| (3) I am able to control the process of creation of a new business. | 0.758 | |

| (4) If I tried to start a new business, I would have a high chance of being successful. | 0.714 | |

| (5) I know most of the practical details needed to start a business. | 0.721 | |

| GS | (1) Government policies (e.g., public procurement) consistently favor new firms. | 0.857 |

| (2) The support for new and growing firms is a high priority for policy at the national government level. | 0.922 | |

| (3) The support for new and growing firms is a high priority for policy at the local government level. | 0.757 | |

| (4) New firms can get most of the required permits and licenses in about a week. | 0.769 | |

| (5) The amount of tax is NOT a burden for new and growing firms. | 0.879 | |

| (6) Taxes and other government regulations are applied to new and growing firms in a predictable and consistent way. | 0.753 | |

| (7) Coping with government bureaucracy, regulations, and licensing requirements is easy for new and growing firms. | 0.720 | |

| (8) A wide range of government assistance for new and growing firms can be obtained through contact with a single agency. | 0.756 | |

| (9) Science parks and business incubators provide effective support for new and growing firms. | 0.772 | |

| (10) There are an adequate number of government programs for new and growing businesses. | 0.791 | |

| (11) The people working for government agencies are competent and effective at supporting new and growing firms. | 0.743 | |

| (12) Almost anyone who needs help from a government program for a new or growing business can find what they need. | 0.821 | |

| (13) Government programs aimed at supporting new and growing firms are effective. | 0.735 |

| Construct | AVE * | Square Root of AVE | CR ** | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | PA | SNs | PBC | GS | ||||

| EI | 0.604 | 0.777 | 0.901 | 1 | ||||

| PA | 0.637 | 0.798 | 0.913 | 0.709 | 1 | |||

| SNs | 0.681 | 0.825 | 0.927 | 0.295 | 0.535 | 1 | ||

| PBC | 0.597 | 0.773 | 0.880 | 0.493 | 0.726 | 0.532 | 1 | |

| GS | 0.628 | 0.792 | 0.956 | 0.401 | 0.509 | 0.160 | 0.376 | 1 |

| Construct | Kolmogorov–Smirnov * Statistic | df | Sig. | Shapiro–Wilk Statistic | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.093 | 362 | 0.000 | 0.971 | 362 | 0.000 |

| PA | 0.131 | 362 | 0.000 | 0.970 | 362 | 0.000 |

| SNs | 0.110 | 362 | 0.000 | 0.979 | 362 | 0.000 |

| PBC | 0.112 | 362 | 0.000 | 0.972 | 362 | 0.000 |

| GS | 0.118 | 362 | 0.000 | 0.969 | 362 | 0.000 |

| Construct | N | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| EI | 362 | −0.166 | 0.128 | −0.886 | 0.256 |

| PA | 362 | −0.194 | 0.128 | −0.568 | 0.256 |

| SNs | 362 | 0.084 | 0.128 | −0.695 | 0.256 |

| PBC | 362 | 0.268 | 0.128 | −0.658 | 0.256 |

| GS | 362 | −0.125 | 0.128 | −0.429 | 0.256 |

| Constructs | Levene Statistic | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI vs. PA | 0.946 | 21 | 340 | 0.531 |

| EI vs. SNs | 2.395 | 24 | 333 | 0.052 |

| EI vs. PBC | 1.479 | 21 | 338 | 0.082 |

| Construct | Range | Mean | Std. Deviation | Mode | Percentiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | 25th | 50th (Median) | 75th | ||||

| EI | 4.00 | 6.83 | 5.52 | 0.639 | 5.67 | 5.00 | 5.58 | 6.00 |

| (1) | 3 | 7 | 5.22 | 0.772 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (2) | 3 | 7 | 5.38 | 1.025 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (3) | 3 | 7 | 5.41 | 0.818 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (4) | 3 | 7 | 5.39 | 0.884 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (5) | 4 | 7 | 5.86 | 0.720 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| (6) | 4 | 7 | 5.84 | 0.755 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| PA | 4.33 | 6.67 | 5.49 | 0.531 | 5.67 | 5.00 | 5.50 | 5.83 |

| (1) | 3 | 7 | 5.00 | 0.829 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| (2) | 4 | 7 | 5.78 | 0.682 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| (3) | 4 | 7 | 5.74 | 0.708 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| (4) | 4 | 7 | 5.86 | 0.730 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| (5) | 4 | 7 | 5.26 | 0.639 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (6) | 3 | 7 | 5.30 | 0.701 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| SNs | 3.00 | 6.50 | 4.74 | 0.706 | 4.50 | 4.17 | 4.67 | 5.33 |

| (1) | 3 | 7 | 4.72 | 0.829 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (2) | 2 | 7 | 4.70 | 0.820 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (3) | 3 | 7 | 4.81 | 0.872 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (4) | 2 | 7 | 4.69 | 0.849 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (5) | 3 | 7 | 4.80 | 0.907 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (6) | 2 | 7 | 4.71 | 0.885 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| PBC | 3.40 | 6.20 | 4.77 | 0.602 | 4.40 | 4.40 | 4.70 | 5.20 |

| (1) | 2 | 6 | 4.56 | 0.814 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (2) | 2 | 7 | 4.35 | 0.861 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) | 3 | 7 | 4.58 | 0.752 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) | 3 | 7 | 5.45 | 0.713 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| (5) | 2 | 7 | 4.92 | 0.838 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| GS | 1.46 | 5.54 | 3.59 | 0.929 | 3.77 | 2.92 | 3.77 | 4.08 |

| (1) | 1 | 7 | 3.97 | 1.302 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (2) | 2 | 7 | 4.12 | 1.270 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (3) | 1 | 7 | 4.07 | 1.258 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (4) | 1 | 7 | 4.02 | 1.154 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (5) | 1 | 6 | 3.46 | 1.114 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| (6) | 1 | 7 | 3.97 | 1.136 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (7) | 1 | 7 | 3.24 | 1.199 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| (8) | 1 | 6 | 3.37 | 1.043 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| (9) | 1 | 7 | 3.48 | 1.109 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| (10) | 1 | 6 | 3.46 | 1.047 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| (11) | 1 | 6 | 3.22 | 0.997 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| (12) | 1 | 5 | 2.90 | 0.927 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| (13) | 1 | 6 | 3.40 | 1.146 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EI | 1 | ||||||

| 2. PA | 0.750 | 1 | |||||

| 3. SNs | 0.594 | 0.633 | 1 | ||||

| 4. PBC | 0.665 | 0.639 | 0.680 | 1 | |||

| 5. PA × GS | 0.473 | 0.541 | 0.351 | 0.490 | 1 | ||

| 6. SNs × GS | 0.362 | 0.396 | 0.629 | 0.529 | 0.877 | 1 | |

| 7. PBC × GS | 0.350 | 0.335 | 0.345 | 0.702 | 0.890 | 0.872 | 1 |

| Overall Model Fit | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple R | 0.790 | |||||||||

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.624 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.620 | |||||||||

| Standard error of the estimate | 0.394 | |||||||||

| Analysis of variance | ||||||||||

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | ||||||

| Regression | 91.890 | 3 | 30.630 | 197.657 | 0.000 | |||||

| Residual | 55.477 | 358 | 0.155 | |||||||

| Total | 147.367 | 361 | ||||||||

| Regression coefficients, correlations, and collinearity statistics | ||||||||||

| Variables | Regression coefficients | Statistical significance | Correlations | Collinearity statistics | ||||||

| B | Std. error | Beta | t | Sig. | Zero-order | Partial | Part | Tolerance | VIF | |

| (Constant) | 0.318 | 0.075 | 4.184 | 0.000 | ||||||

| PA | 0.632 | 0.054 | 0.526 | 11.672 | 0.000 | 0.750 | 0.525 | 0.379 | 0.518 | 1.930 |

| SNs | 0.064 | 0.043 | 0.070 | 1.488 | 0.138 | 0.594 | 0.078 | 0.048 | 0.471 | 2.122 |

| PBC | 0.299 | 0.051 | 0.281 | 5.915 | 0.000 | 0.665 | 0.298 | 0.192 | 0.465 | 2.152 |

| Overall Model Fit | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple R | 0.868 | |||||||||

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | 0.753 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.749 | |||||||||

| Standard error of the estimate | 0.320 | |||||||||

| Analysis of variance | ||||||||||

| Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. | ||||||

| Regression | 110.991 | 6 | 18.498 | 180.528 | 0.000 | |||||

| Residual | 36.376 | 355 | 0.102 | |||||||

| Total | 147.367 | 361 | ||||||||

| Regression coefficients, correlations, and collinearity statistics | ||||||||||

| Variables | Regression coefficients | Statistical significance | Correlations | Collinearity statistics | ||||||

| B | Std. error | Beta | t | Sig. | Zero-order | Partial | Part | Tolerance | VIF | |

| Block 1 | ||||||||||

| (Constant) | 0.224 | 0.065 | 3.413 | 0.001 | ||||||

| PA | 0.514 | 0.133 | 0.506 | 3.845 | 0.000 | 0.750 | 0.518 | 0.414 | 0.593 | 1.687 |

| SNs | 0.023 | 0.138 | 0.025 | 0.169 | 0.866 | 0.594 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.586 | 1.705 |

| PBC | 0.253 | 0.087 | 0.240 | 2.888 | 0.004 | 0.665 | 0.245 | 0.209 | 0.626 | 1.598 |

| Block 2 | ||||||||||

| PA × GS | 0.026 | 0.006 | 0.151 | 4.110 | 0.000 | 0.473 | 0.152 | 0.127 | 0.314 | 3.182 |

| SNs × GS | −0.013 | 0.041 | −0.082 | −0.310 | 0.757 | 0.362 | −0.016 | −0.010 | 0.782 | 1.278 |

| PBC × GS | 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.138 | 2.669 | 0.008 | 0.350 | 0.131 | 0.109 | 0.401 | 2.495 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, T.; Khalid, N.; Ahmed, U. Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention among Foreigners in Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137066

Yu T, Khalid N, Ahmed U. Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention among Foreigners in Kazakhstan. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137066

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Tongxin, Nadeem Khalid, and Umair Ahmed. 2021. "Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention among Foreigners in Kazakhstan" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137066

APA StyleYu, T., Khalid, N., & Ahmed, U. (2021). Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention among Foreigners in Kazakhstan. Sustainability, 13(13), 7066. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137066