Disentangling Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information and Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Thermostatistics

2.1. Thermodynamics: Principle Versus Law

2.2. Statistical Mechanics: Reductionism Versus Emergentism

- Prior distribution: What phase probability distribution should be used as a starting point for calculations, considering that it cannot be measured?

- Equilibrium: Since phases are never stationary, a definition of equilibrium other than that of thermodynamics is necessary. Which one?

- Joining two identical volumes of the same gas increases the volume accessible to each particle and therefore the total number of possibilities for the system and its Gibbs entropy. However, this occurs without heat exchange and thus without variation of Clausius entropy. The system can return to the initial state at no work, simply by replacing the partition between the two volumes.

- Mixing two volumes of gas requires work to return to the initial state only if these two gases were initially identified as different. However for statistical mechanics, both cases increase entropy because replacing the partition between the two volumes is not enough to ensure that each particle returns to its original compartment.

2.3. Information Theory: The Return of the Observer

- In no case, the average number of bits per character is less thanH is named quantity of information emitted by the source and by identification with Equation (1), is its entropy.

- Within a factor, H (and thus S) is the only measure of uncertainty on the upcoming character that is (1) continuous in p; (2) increasing in for uniform distributions; and (3) additive over different independent sources of uncertainty.

3. Information and Demons

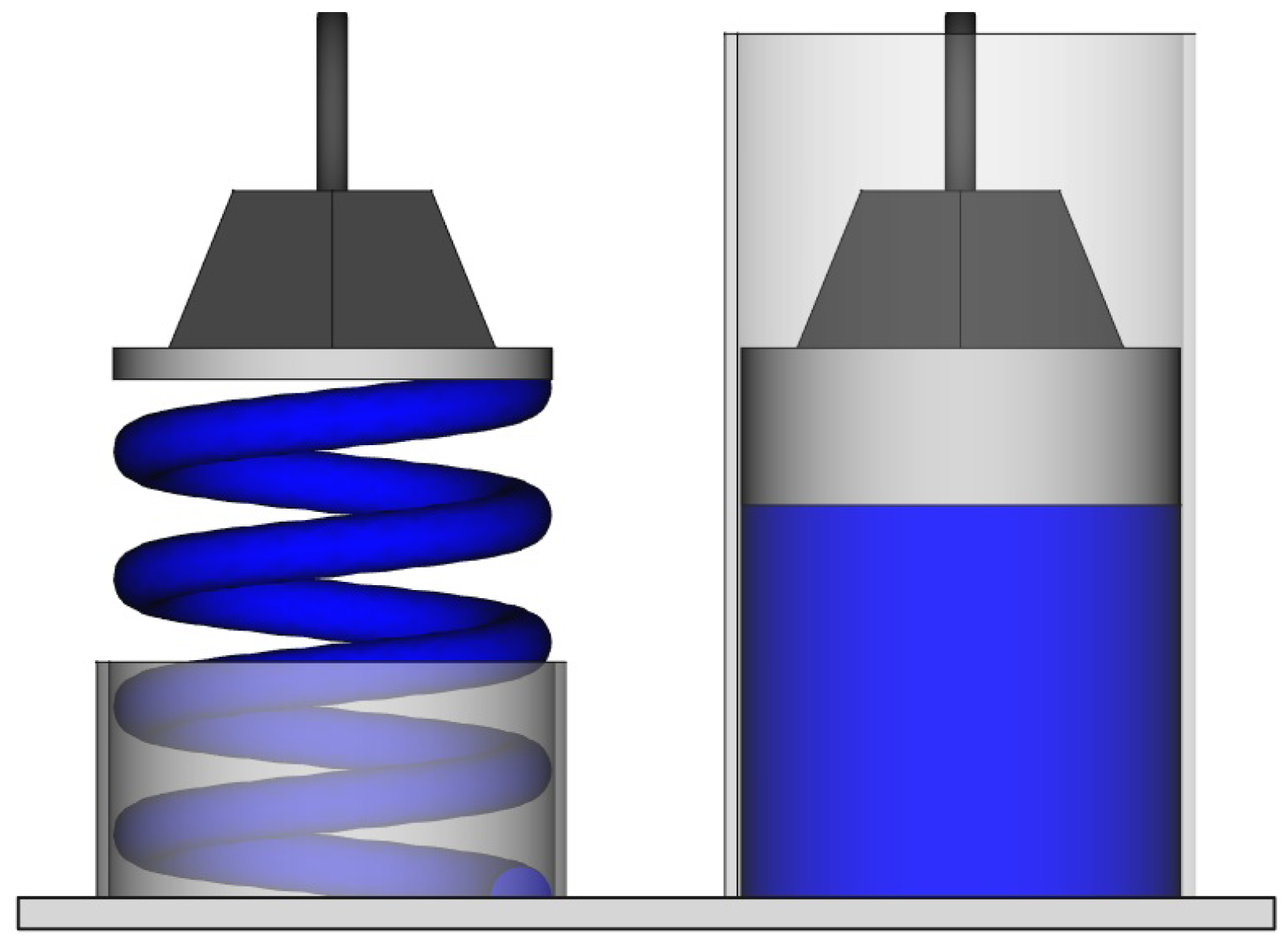

3.1. From Maxwell to Szilard

3.2. Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information

- Clausius: The negative of the entropy difference experienced by a system (at a given T) is the minimum work W that must be performed on the system for the change to take place: .

- Gibbs: Entropy S is related to the probability distribution of possible microstates.

- Shannon: The Gibbs formula for S is actually to a factor of that of the uncertainty H on the actual microstate:

- 4.

- Brillouin: Therefore, reducing uncertainty by acquiring information requires minimum work: . For one bit of acquired information ; thuswhere is the minimum work that we have to provide (and that will be dissipated as heat) per bit of acquired information. This is the Brillouin’s negentropy law of information [6,7], called “principle” by Brillouin [6] and sometimes referred to as Szilard’s principle [38], since Equation (4) can be derived from the operation of the Szilard engine. Here, however, it is referred to as a “law” for the sake of consistency with Section 2.1, because it is derived from the second law. With Brillouin’s equation, the energy balance of the Szilard engine is zero, as required.

3.3. Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure

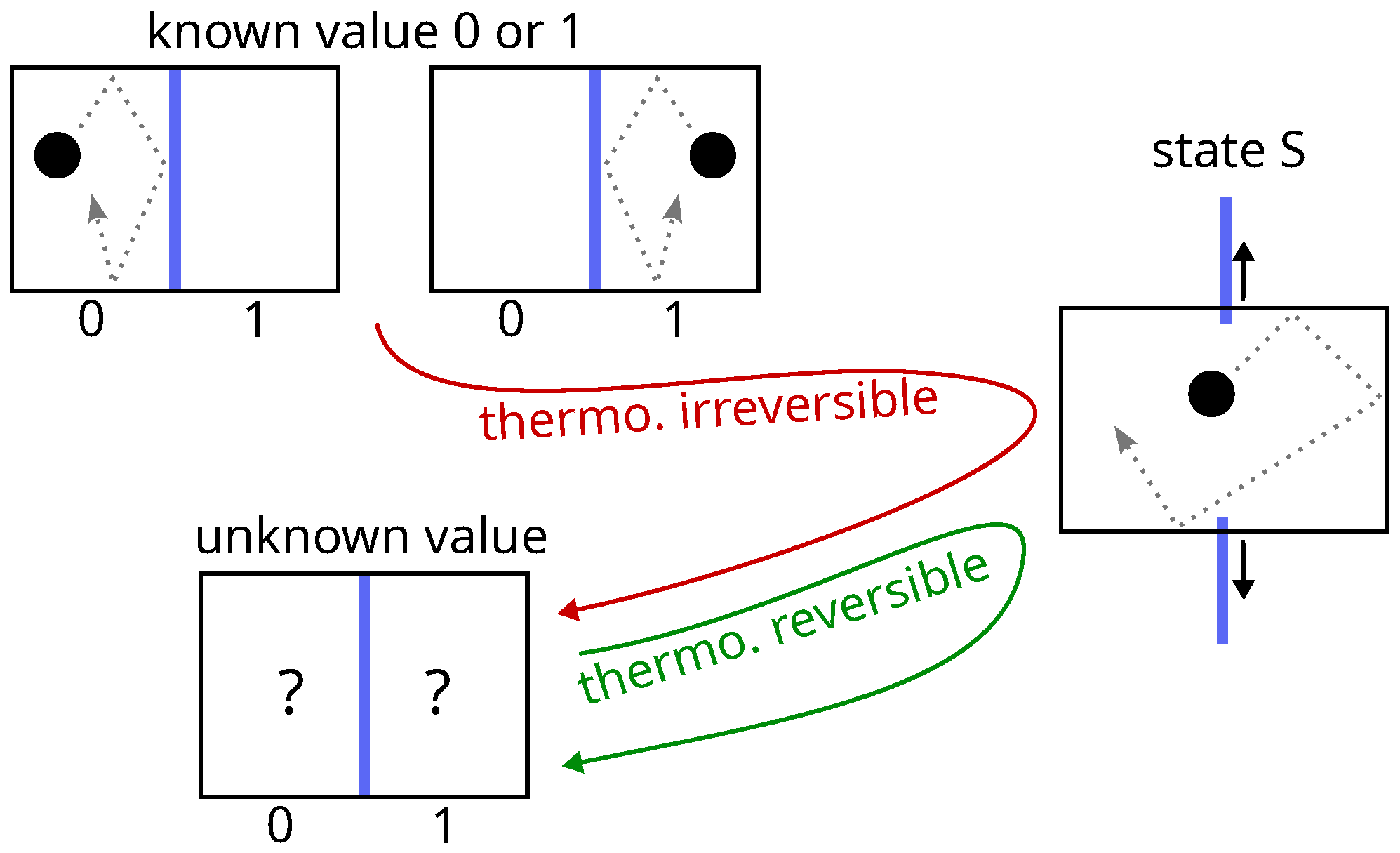

- Any intelligent being has a finite memory; thus, the infinite cyclic acquisition of information about a dynamical system necessarily requires the erasure of data bits.

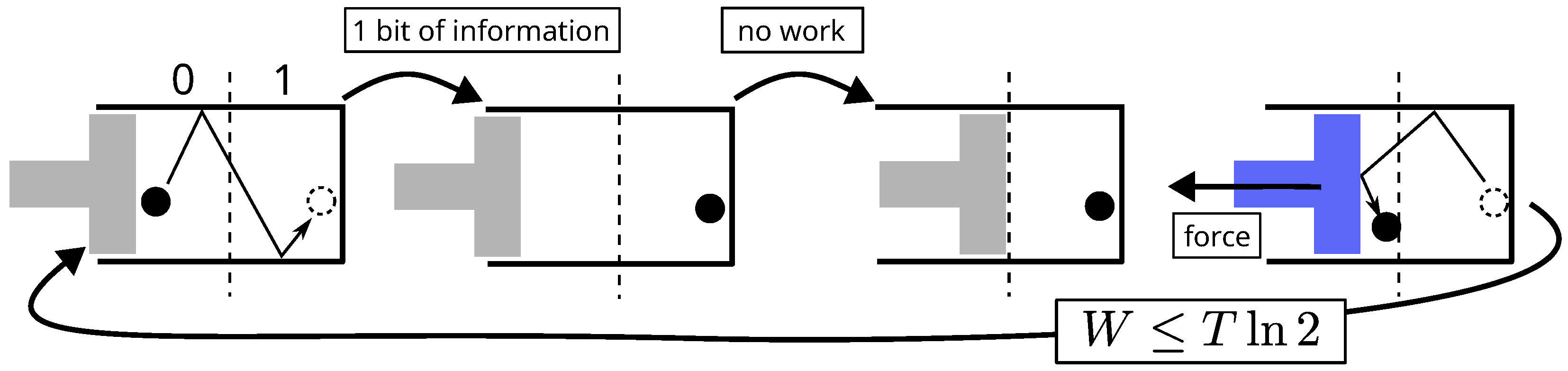

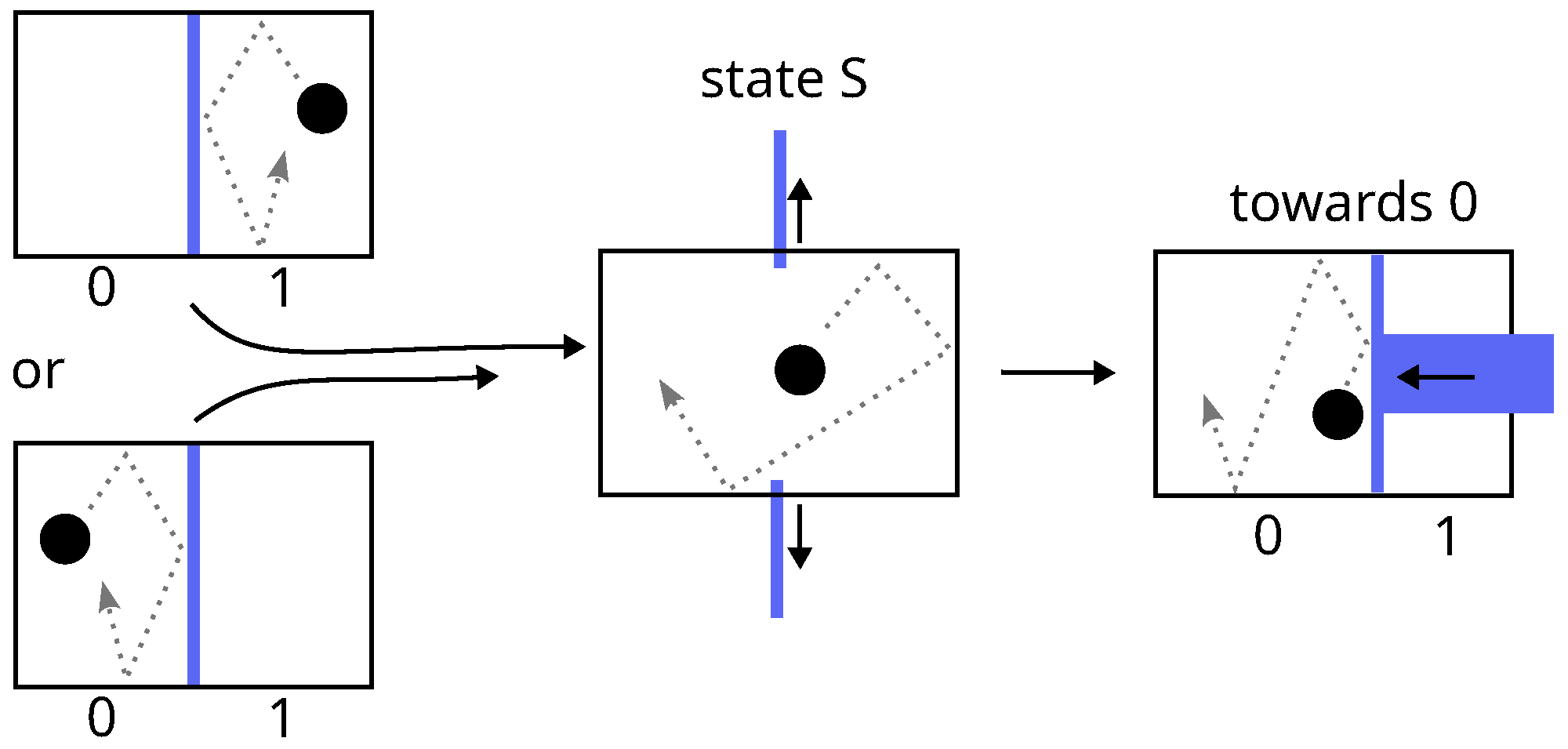

- Erasing a data bit (a thermodynamical system) consists of setting it to an arbitrary value (say 0). The procedure must be able to work for a known or unknown initial value (i.e., it must be the same in both cases). This constraint automatically implies a two-step erasure process (see Figure 3):

- (a)

- Free expansion of the phase space by a factor 2, leading the system to an undetermined standard state (state S).

- (b)

- Quasi-static compression of the phase space by the same factor leading the system from state S to state 0.

- The first step does not involve any exchanges with the environment, whereas the second dissipates at least of heat, or equivalently, at constant internal energy (i.e., at constant temperature for a set of independent data bits), it requires a minimum work. The net balance of the two yieldswhich leads, as Brillouin’s law does (Equation (4)), to a zero energy balance for Szilard engine. The difference lies in the fact that, according to Landauer, erasure is a necessary step, and it is at this very point that the energy cost of data acquisition is paid.

- Restricted context of data erasure: Does erasing one data bit really require at least (Landauer’s limit) of work?To my knowledge, all the authors (see, e.g., [39,40,41,42,43,44]) who have addressed this question actually used Landauer’s procedure that consists of (a) free expansion; (b) reversible compression. In this way, the authors simply test the second law rather than the novel aspect of Landauer’s idea; therefore, their results are unsurprising, as there is no error in Landauer’s calculation. What is new in Landauer’s assertion? It is the claim that there is no alternative erasing procedure. Thus, the only way to confirm Landauer’s law would be to search, in vain, for an alternative. However, this is not what was done. In reality, even within the restricted context of data erasure, several points of Landauer’s reasoning are questionable: the imperative to begin erasure with expansion, and the necessity of this expansion to be thermodynamically irreversible. Counterexamples have been provided [45,46,47], which invalidate the generality of Landauer’s procedure.

- Broader context of information acquisition and loss: Does data erasure equate to information loss? Can Landauer’s law on data erasure be considered as the missing link between information and energy, something that would replace Brillouin’s law of information? In the following section, we focus on the inconsistencies this idea introduces by confusing information and data.

4. Information Versus Data

4.1. Total Versus Incomplete Information

4.2. Global Concept Versus Local Object

4.3. Pair of States Versus Path

5. Conclusive Epistemological Point

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1966; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, E. Energy and Change. Phys. Teach. 2007, 45, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.C. Theory of Heat, 3rd ed.; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Brillouin, L. The Negentropy Principle of Information. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. Science and Information Theory; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Information is Physical. Phys. Today 1991, 44, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. The physical nature of information. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 217, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. The Gibbs Paradox, the Landauer Principle and the Irreversibility Associated with Tilted Observers. Entropy 2017, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. Landauer Principle and General Relativity. Entropy 2020, 22, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.; Neurath, O.; Carnap, R. The scientific conception of the world: The Vienna Circle. In Empiricism and Sociology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, E. History and Root of the Principle of the Conservation of Energy; The Open Court Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, E. The Science of Mechanics; The Open Court Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Carnap, R. Philosophical Foundations of Physics; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Duhem, P. The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poincaré, H. Science and Hypothesis; The Walter Scott Publishing Co.: London, UK, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Poincaré, H. The Value of Science; The Science Press: New York, NY, USA, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. On the method of theoretical physics. Philos. Sci. 1934, 1, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.C. Diffusion. Encycl. Br. Reprod. Sci. Pap. 1878, 2, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. A short derivation of Boltzmann distribution and Gibbs entropy formula from the fundamental postulate. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.02455v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entropy, Special Issue ‘Gibbs Paradox and Its Resolutions’. 2009. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy/special_issues/gibbs_paradox (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Entropy, Special Issue ‘Gibbs Paradox 2018’. 2018. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy/special_issues/Gibbs_Paradox_2018 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Gibbs, J.W. On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances: First [-Second] Part; Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences: New Haven, CT, USA, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. Thermostatistics, Information, Subjectivity: Why Is This Association So Disturbing? Mathematics 2024, 12, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. Plea for the use of the exact Stirling formula in statistical mechanics. SciPost Physics Lecture Notes 2023, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callen, H.B. Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, 2nd ed.; J. Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Poincaré, H. Chapitre II. Théorie des invariants intégraux. Acta Math. 1890, 13, 46–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balian, R. From Microphysics to Macrophysics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubs, H. The principle of insufficient reason. Philos. Sci. 1942, 9, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. Remarks on an alleged proof of the “Method of least squares,” contained in a late number of the Edinburgh review. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1850, 37, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. II. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, J.; Johnson, R. Axiomatic derivation of the principle of maximum entropy and the principle of minimum cross-entropy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1980, 26, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. The well-posed problem. Found. Phys. 1973, 3, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilard, L. On the decrease of entropy in a thermodynamic system by the intervention of intelligent beings. Behav. Sci. 1964, 9, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earman, J.; Norton, J.D. EXORCIST XIV: The Wrath of Maxwell’s Demon. Part II. From Szilard to Landauer and Beyond. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 1999, 30, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyabe, S.; Sagawa, T.; Ueda, M.; Muneyuki, E.; Sano, M. Experimental demonstration of information-to-energy conversion and validation of the generalized Jarzynski equality. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.; Gavrilov, M.; Bechhoefer, J. High-Precision Test of Landauer’s Principle in a Feedback Trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 190601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E.; Ciliberto, S. Information: From Maxwell’s demon to Landauer’s eraser. Phys. Today 2015, 68, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lambson, B.; Dhuey, S.; Bokor, J. Experimental test of Landauer’s principle in single-bit operations on nanomagnetic memory bits. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciliberto, S.; Lutz, E. The physics of information: From Maxwell to Landauer. In Energy Limits in Computation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzi, R.; Burzurí, E.; Maegawa, S.; van der Zant, H.S.J.; Luis, F. Quantum Landauer erasure with a molecular nanomagnet. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. Thermodynamical versus Logical Irreversibility: A Concrete Objection to Landauer’s Principle. Entropy 2023, 25, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. On the Supposed Mass of Entropy and That of Information. Entropy 2024, 26, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairez, D. The Fundamental Difference Between Boolean Logic and Thermodynamic Irreversibilities, or, Why Landauer’s Result Cannot Be a Physical Principle. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroney, O. The (absence of a) relationship between thermodynamic and logical reversibility. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 2005, 36, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H. Notes on Landauer’s principle, reversible computation, and Maxwell’s Demon. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 2003, 34, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. The mass of a bit of information and the Brillouin’s principle. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2014, 13, 1450002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M.M. The mass-energy-information equivalence principle. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 095206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M.M. Experimental protocol for testing the mass-energy-information equivalence principle. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 035311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.C. Brief history of the debate. In The Physics of Emergence (Second Edition); IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, G.; Parravicini, A. Introduction to Pragmatism and Theories of Emergence. Eur. J. Pragmatism Am. Philos. 2019, XI-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hani, C.N.; Pihlström, S. Emergence Theories and Pragmatic Realism. Essays Philos. 2002, 3, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lairez, D. Disentangling Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information and Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure. Entropy 2026, 28, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010037

Lairez D. Disentangling Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information and Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleLairez, Didier. 2026. "Disentangling Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information and Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure" Entropy 28, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010037

APA StyleLairez, D. (2026). Disentangling Brillouin’s Negentropy Law of Information and Landauer’s Law on Data Erasure. Entropy, 28(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010037