1. Introduction

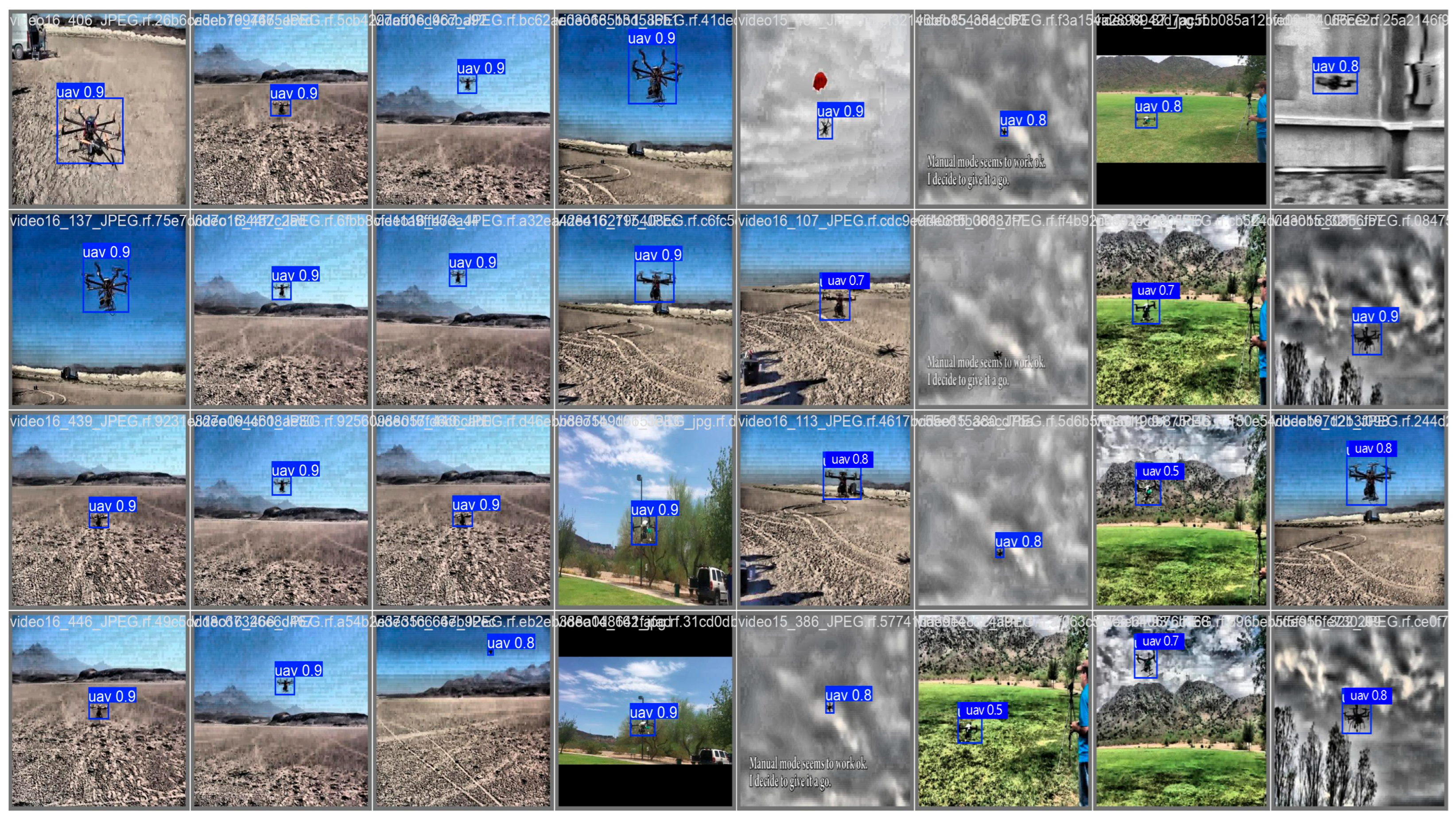

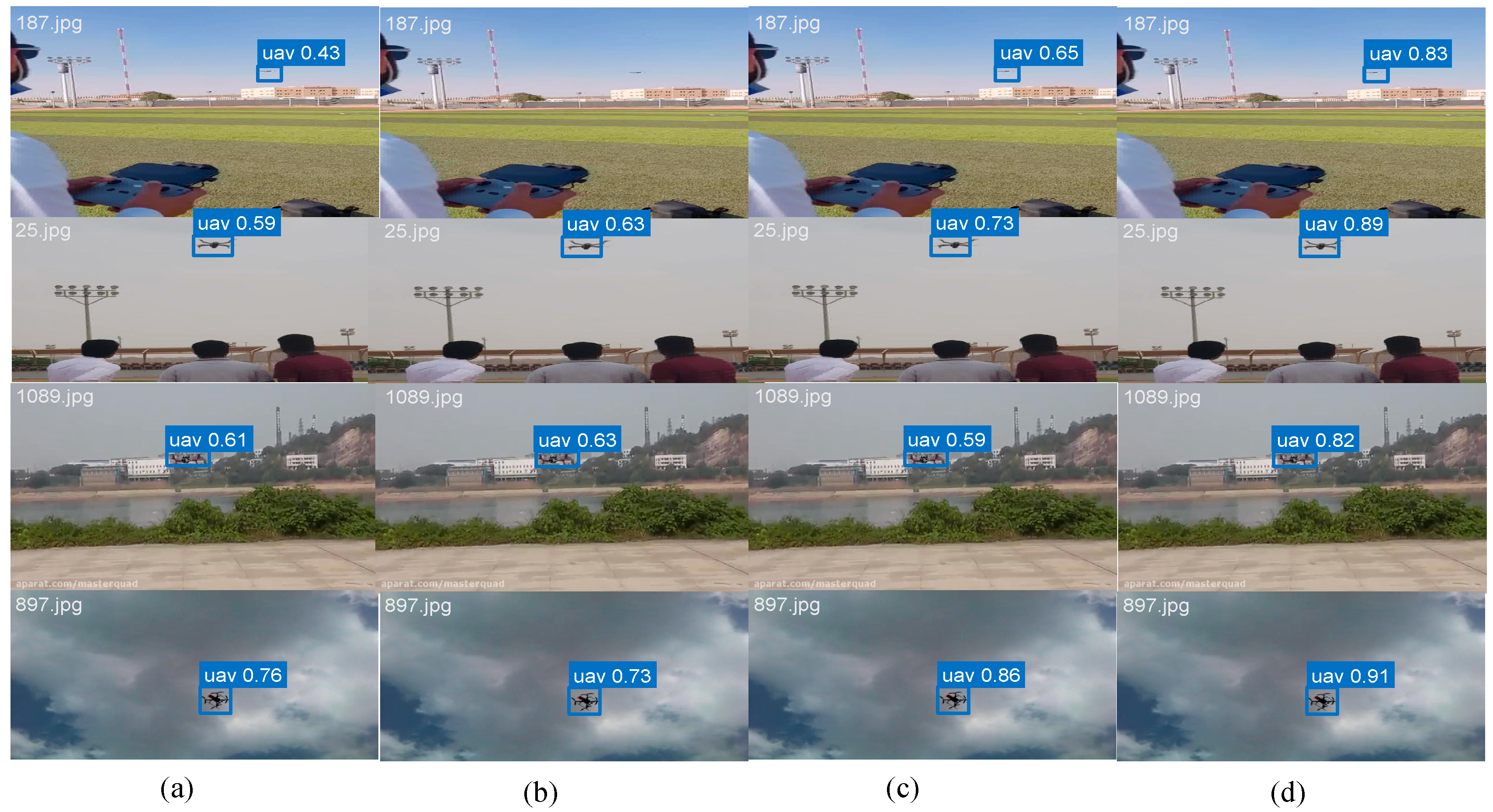

The rapid proliferation of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has ushered in transformative advancements across various sectors, but it has simultaneously created a pressing and formidable challenge for security and surveillance systems: the reliable detection of low-altitude, slow-speed, and small (LSS) drones. These LSS UAVs, often utilized for recreational, commercial, and, disconcertingly, unauthorized purposes, inherently operate in a regime that poses extreme difficulties for conventional vision-based detectors. The core of this challenge lies in the pervasive uncertainty that dominates their observation. This uncertainty is multifaceted, stemming from their minimal visual signature—often appearing as what we term sub-pixel entities in the image plane. In this context, we define a “sub-pixel target” as one with a spatial extent typically smaller than 16 × 16 pixels; consequently, “sub-pixel localization” refers to the task of estimating its center coordinates with a precision that transcends the discrete pixel grid, thereby directly mitigating the severe quantization errors—their propensity to blend into complex and cluttered urban backgrounds, and, most critically, their frequent operation during adverse imaging conditions such as low light, haze, fog, and motion blur.

From a sensing and perception standpoint, these adverse conditions introduce significant aleatoric uncertainty—irreducible noise inherent in the observation process. In low-light scenarios, the signal-to-noise ratio plummets; haze and fog cause atmospheric scattering that washes out contrast and color; motion blur further smears fine details. For a deterministic object detector, this ambiguous and noisy sensory input forces the model to make a single, often overconfident, “best guess.” Consequently, these models suffer from pronounced performance drops, characterized by a high rate of missed detections when visual evidence is weak and false alarms triggered by spurious background patterns that resemble a drone under degradation.

A Bayesian perspective offers a principled framework to address this limitation. It posits that a robust detection system in such a high-uncertainty regime should not only output a point estimate but also a well-calibrated measure of confidence or uncertainty in that prediction. This allows downstream systems to make risk-aware decisions. While recent research has made commendable strides in developing lightweight architectures for aerial imagery—evidenced by LEAF-YOLO’s [

1] efficient attention modules and LI-YOLO’s [

2] integrated low-light enhancements—a critical gap remains. Few works have explicitly and systematically addressed the core issue of

modeling and leveraging uncertainty under the real-world, degraded conditions that are defining for the LSS UAV detection task. These advanced models, including other enhancements to the YOLO family, often lack the probabilistic grounding to express predictive uncertainty, leading to overconfident predictions on ambiguous data when the system should, in essence, be able to express “I don’t know” with high confidence.

Motivated by this gap, we present GAME-YOLO, an end-to-end detection framework whose design is fundamentally guided by the principles of Bayesian inference and probabilistic reasoning, tailored explicitly for the high-uncertainty regime of LSS UAV detection. Our core insight is to re-interpret and augment key components of a modern, efficient detector like YOLOv11 [

3] through a probabilistic lens. We deliberately avoid the computational prohibitive path of full Bayesian neural networks, which are unsuitable for real-time tasks, and instead embed strategically designed, Bayesian-inspired mechanisms that enhance robustness and calibration without sacrificing efficiency:

- (1)

The Visibility Enhancement Module (VEM) [

4] acts as a prior, probabilistically inferring the latent, clear image from a noisy, degraded observation.

- (2)

The Global Attention mechanism [

5] functions as a data-dependent prior, guiding the model to focus computational resources on image regions most likely to contain objects, reducing uncertainty from cluttered backgrounds.

- (3)

The Adaptive Multi-Scale Fusion mimics Bayesian [

6] model averaging, dynamically combining evidence from different feature scales to arrive at a more robust and uncertainty-reduced prediction.

- (4)

The Shape-Aware Loss [

7] can be viewed as shaping the posterior distribution over bounding boxes, penalizing implausible shapes and encouraging predictions that are consistent with the data and prior geometric knowledge.

By integrating these components, GAME-YOLO moves beyond a purely deterministic mapping. It embodies a practical application of Bayesian thinking for edge deployment, where efficiently managing predictive uncertainty is paramount for reliability. We demonstrate through extensive experiments that this approach not only achieves state-of-the-art accuracy on challenging benchmarks like LSS2025-DET but also leads to better-calibrated and more trustworthy detection outputs in low-visibility scenarios, thus providing a crucial step towards dependable autonomous surveillance systems.

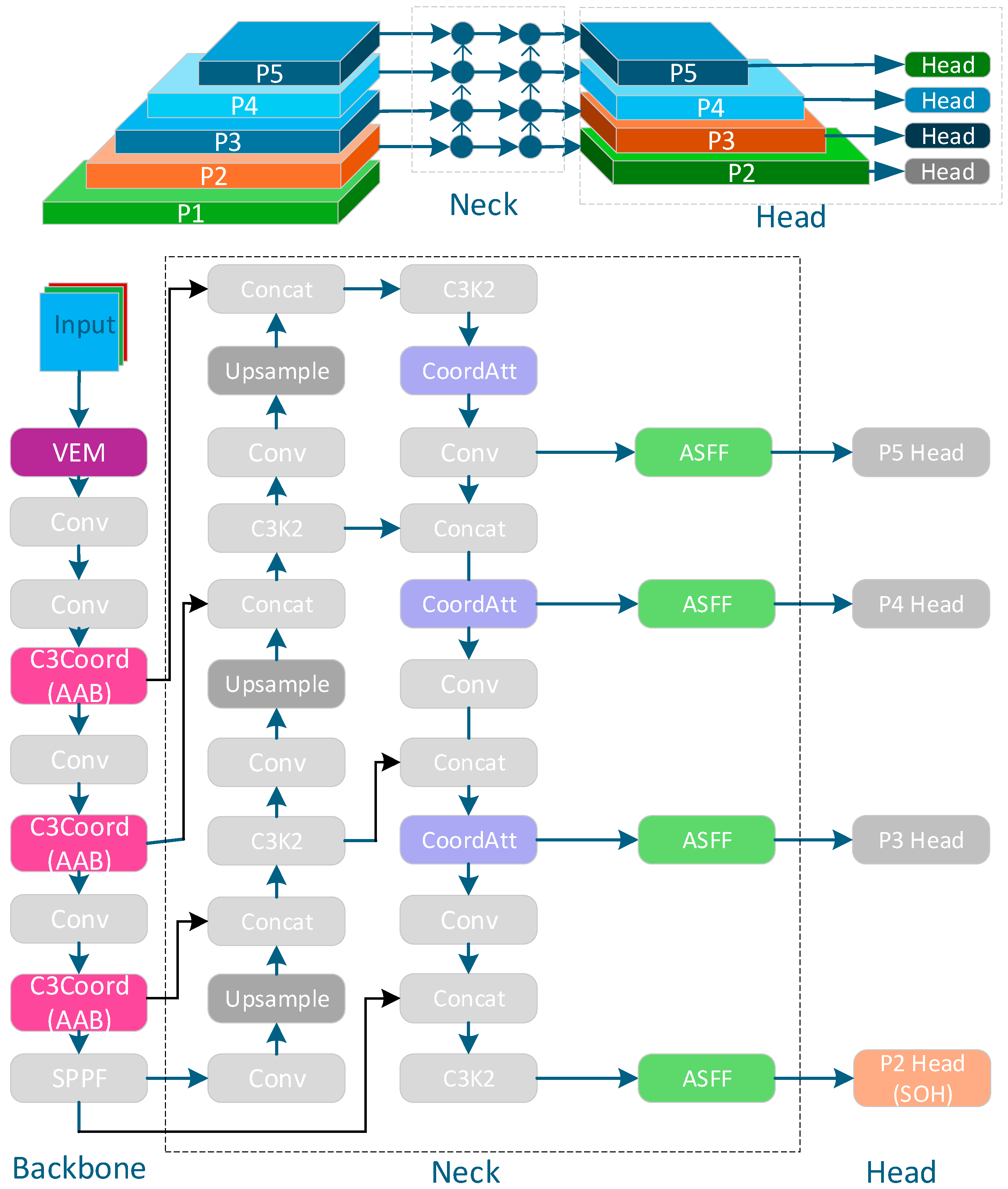

3. Methodology

Uncertainty Modeling Framework in GAME-YOLO. While GAME-YOLO does not employ stochastic weights or Monte Carlo sampling, it implements a practical uncertainty-aware pipeline that addresses aleatoric uncertainty at different stages of processing. The flow of information and the progressive refinement of uncertainty can be conceptualized as follows: The VEM first reduces uncertainty at the input level by recovering a clearer signal from degraded data. The AAB then reduces uncertainty at the feature level by selectively amplifying informative regions and suppressing noise. The MSFN further reduces uncertainty at the representation level by robustly integrating multi-scale evidence. Finally, the Shape-Aware IoU Loss shapes the learning to be more sensitive to localisation uncertainty, particularly for small objects. This cascaded design ensures that uncertainty is progressively mitigated, resulting in more reliable and better-calibrated final predictions.

Built upon the YOLOv11 architecture, GAME-YOLO integrates five collaboratively designed modules to enhance detection of low-visibility, small UAVs including near-sub-pixel targets, defined as those occupying <16 × 16 pixels in input images or 1–4 grid cells in backbone feature maps while maintaining real-time performance.

The proposed method has two core components—Global Attention in the backbone and Multi-Scale Enhancement in the neck—hence GAME-YOLO. The global attention machanism includes a font-end Visibility Enhancement Module (VEM) restores contrast and texture in low-light or hazy frames; the backbone then augments native C2f blocks with CoordAttention and self-calibrated attention to inject long-range context and channel–spatial selectivity for small, near–sub-pixel targets. Downstream, the Multi-Scale Fusion Neck (MSFN) extends PAFPN with a bottom-up feedback path, and before each upsample, ASFF and lightweight CoordBlock layers reconcile cross-scale features so high-resolution cues are preserved rather than aliased. In short: global context up top, multi-scale precision downstream—GAME in name and in design.

The detection head introduces a Small-Object Head (SOH) at the P2 level (stride = 4), leveraging high-resolution feature maps and local attention to better detect sub-pixel UAVs. The loss function combines Shape-Aware IoU (SAIoU) for regression with Focal-BCE for classification, incorporating scale-aware penalties to handle tiny object imbalance effectively.

Future work may explore domain-adaptive training strategies to improve generalization under cross-modal or extreme visibility shifts. The overall architecture of GAME-YOLO is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Visibility Enhancement Module (VEM)

We introduce a VEM prior to the YOLOv11 backbone to enhance image quality under low-light, haze, and motion-blurred conditions. This module adaptively improves contrast, brightness, and detail preservation, ensuring that tiny UAVs remain clearly visible during subsequent convolutional feature extraction.

As shown in

Figure 2, the module consists of two subnetworks: an illumination estimation subnetwork and a self-calibration subnetwork. First, the illumination estimation subnetwork boosts global and local brightness and contrast, generating a preliminary enhanced intermediate image. Next, the self-calibration subnetwork refines this intermediate image by residual correction, restoring texture details potentially lost during enhancement and suppressing amplified noise and color deviations.

The VEM operates as a composite function that transforms a degraded input image into an enhanced version through sequential processing:

- (1)

Illumination Estimation Subnetwork

Let

denote the input low-visibility image. The illumination estimation subnetwork

generates a preliminary enhanced image:

where:

is preliminary enhanced intermediate image,

is global illumination adjustment map,

is local brightness enhancement map,

denotes element-wise multiplication. The global adjustment map is computed as:

where

is the sigmoid function,

and

are learnable parameters, and

denotes convolution.

- (2)

Self-Calibration Subnetwork

The self-calibration subnetwork

refines the preliminary result through residual correction:

where:

is Residual correction term,

is Convolutional layer with kernel size

.

- (3)

Final Enhancement Output

The complete VEM enhancement is formulated as a residual learning process:

where the comprehensive enhancement function

encapsulates both subnetworks:

where

is composite enhancement function encompassing both subnetworks,

and

are learnable weighting coefficients initialized to 0.5. The parameters

and

are optimized during training to balance the contributions of illumination adjustment and detail preservation. This mathematical formulation provides a principled basis for the VEM’s image enhancement capability while maintaining the residual learning framework described in the original text.

This approach effectively improves contrast and detail recovery while preventing excessive alteration or degradation of the original image structure. Within the GAME-YOLO framework, this enhancement module is decoupled from the main detection backbone and can be trained independently or jointly with the backbone network. The enhanced image directly replaces the original input for the YOLOv11 backbone. This modular design significantly improves detection performance under challenging environmental conditions without introducing substantial computational overhead.

From a Bayesian perspective, the VEM implements a prior over image quality, probabilistically inferring the latent clear image from the degraded observation . This can be viewed as maximizing , reducing input-level aleatoric uncertainty before feature extraction.

3.2. Attention-Augmented Backbone (AAB)

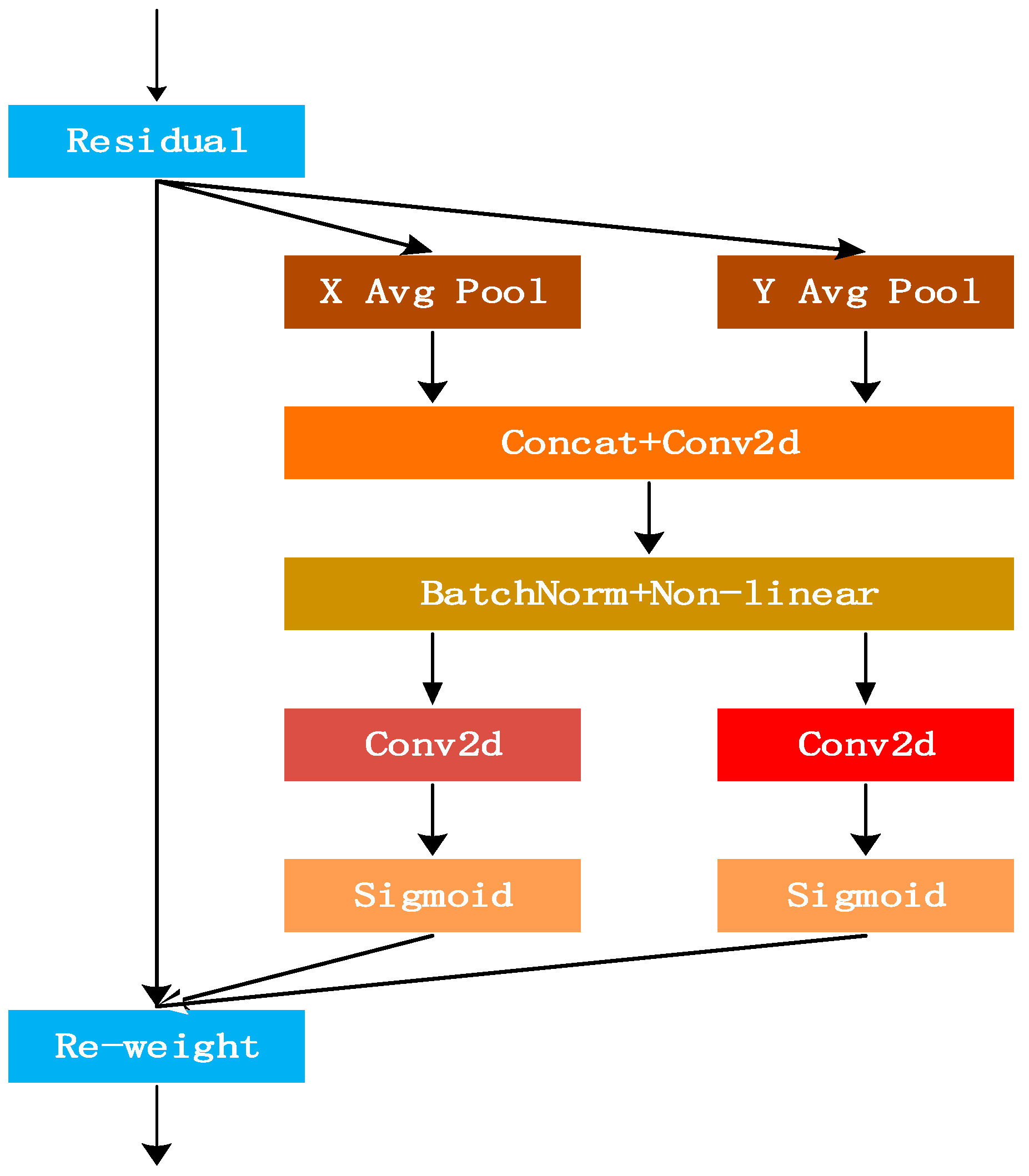

To empower the YOLOv11 backbone with heightened sensitivity towards small, low-visibility targets, we propose an Attention-Augmented Backbone (AAB). The core challenge in detecting sub-pixel UAVs lies in the irreversible loss of fine-grained spatial information through successive pooling and convolutional strides in the standard backbone. While effective for capturing hierarchical features, these operations act as low-pass filters, blurring the precise locations of tiny objects. To counter this, we integrate a lightweight CoordAttention mechanism into the critical C3K2 modules of the backbone. Unlike channel-only attention (e.g., SE) or complex spatial-channel attention (e.g., CBAM), CoordAttention offers a novel and efficient paradigm by decomposing the global attention process into complementary horizontal and vertical directions. This enables the backbone to not only “see” what is important (channel-wise) but also precisely “where” it is located (long-range spatial context), thereby directly mitigating the positional ambiguity introduced by downsampling.

The CoordAttention module operates through a structured four-stage process, as conceptually illustrated below (

Figure 3):

This design advantageously encodes global positional information effectively with minimal computational overhead, enhancing both channel-wise and spatial feature representation capabilities. The mathematical formulation is defined as follows:

- (1)

Coordinate Information Embedding

Instead of using global average pooling which collapses all spatial information into a single channel-wise descriptor, CoordAttention factorizes the process. For an input feature map

, it employs two separate 1D global pooling kernels along the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. This produces two direction-aware feature maps:

Here, is the output of horizontal global pooling (X-Pool), encoding width-wise global context for each row, is the output of vertical global pooling (Y-Pool), encoding height-wise global context for each column, denotes the c-th channel of the input feature map .

- (2)

Coordinate Attention Generation

The concatenated feature maps

are then transformed via a shared 1 × 1 convolutional filter

and a nonlinear activation to generate intermediate feature maps

and

containing horizontal and vertical context information, respectively. These are split and passed through sigmoid activation

σ to produce the final attention weights:

Here, is the attention map in the height direction, is the attention map in the width direction, denotes the shared 1 × 1 convolution that reduces computational cost while facilitating cross-channel interaction.

- (3)

Feature Recalibration

The final output

of the CoordAttention module is obtained by multiplicatively recalibrating the input features with the generated attention maps:

Here, is the output feature value at channel and position , is the input feature value at channel and position , is the height-direction attention weight for channel at row , is the width-direction attention weight for channel at column .

The design of CoordAttention directly addresses the core limitation raised by the reviewer. By decomposing spatial attention into one-dimensional, long-range interactions, the module achieves several key advantages for tiny object detection:

- (1)

Preserves Precise Spatial Coordinates: The directional pooling explicitly encodes the absolute positional information of features along the height and width dimensions. Even after aggressive downsampling in deeper layers, the network can leverage this coordinate “memory” to maintain the location of a sub-pixel target that might otherwise be lost in standard global pooling.

- (2)

Captures Global Context with Minimal Cost: The 1D pooling strategy is computationally lightweight ( complexity) compared to 2D global pooling, yet it effectively captures dependencies across the entire image. This allows the model to understand that a tiny UAV is often part of a larger structural context (e.g., against the sky or between buildings), enhancing its discriminative power against clutter.

- (3)

Enhances Spatial Sensitivity: The multiplicative recalibration in Step 3 selectively amplifies features at informative locations while suppressing uninformative ones. For a slender drone rotor or a small fuselage, this means that the specific rows and columns where the object resides receive higher activation, making the feature representation more spatially precise.

In GAME-YOLO, we integrate this CoordAttention module into the critical downsampling C3K2 blocks of the backbone. This strategic placement ensures that positional cues are reinforced at the very stages where they are most vulnerable to being lost. The result is a backbone that is not only semantically rich but also spatially intelligent, leading to the significant improvements in recall and localization accuracy for tiny UAVs observed in our experiments, all while maintaining the computational efficiency required for real-time inference.

The global attention mechanism functions as a data-dependent prior adaptively focusing on regions most likely to contain objects. This Bayesian-inspired feature selection reduces uncertainty propagation by suppressing noisy background features while amplifying informative foreground signals.

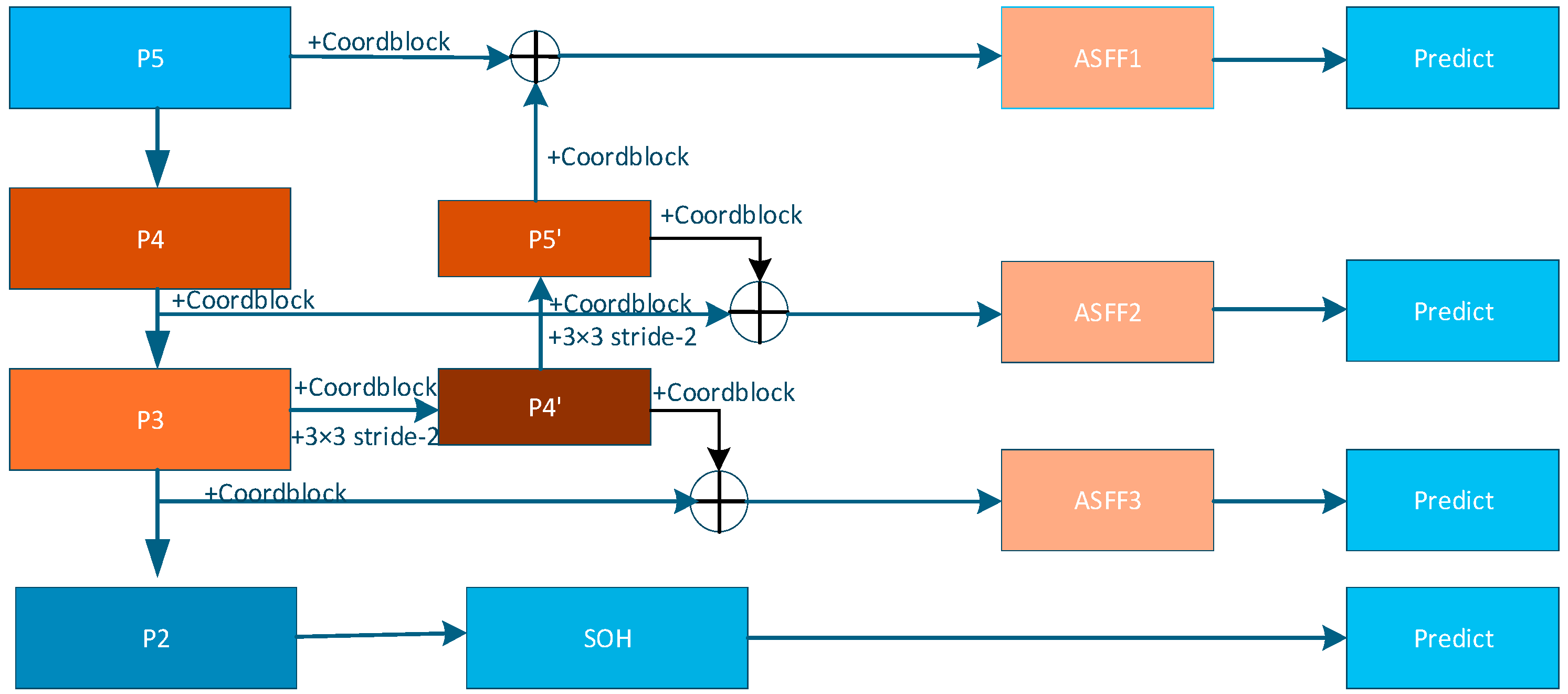

3.3. Multi-Scale Fusion Neck (MSFN)

Deep layers carry strong semantics but poor spatial detail, whereas shallow layers preserve edges but lack context. This imbalance is the root hurdle for small-object detection. As illustrated in

Figure 4, a conventional PAFPN offers only a top-down stream, and naïvely concatenating or summing multi-scale features cannot adaptively select the most informative scales for a given scene.

On top of the original top-down path (P5 → P4 → P3), GAME-YOLO introduces a bottom-up feedback chain (P3 → P4′ → P5′). Concretely, P3 is compressed by a 3 × 3 stride-2 conv to form P4′ and channel-wise fused with P4; P4′ is then down-sampled to P5′ and merged with P5, establishing a “semantic–detail” loop that continuously embeds shallow textures into deep semantics.

Before every up- or down-sampling, a CoordBlock (CoordConv plus CoordAttention) is inserted. CoordConv explicitly injects absolute (i, j) coordinates; CoordAttention then produces direction-aware weights along height and width, simultaneously keeping spatial cues and recalibrating channels with negligible cost. This step prevents tiny-object coordinates from being washed out during resampling.

At each fusion node among P3, P4, P5 and their feedback layers, ASFF computes branch weights {

} via the Softmax formulation above:

where, Align (·) resizes features to a common resolution. ASFF lets the network automatically prioritize the most discriminative scales for a given scene, yielding more stable confidences and more precise box regression than fixed concatenation.

The adaptive neck complements the P2 tiny-object head: shallow details reinforced by the feedback path are further exploited by scale-aware losses at the head stage, while the coordinate-sensitive features generated by CoordBlock, together with the VEM-enhanced inputs, safeguard localization accuracy for tiny targets in low-visibility scenarios.

The multi-scale fusion strategy emulates Bayesian model averaging, where predictions from different scales are combined with data-dependent weights. This can be interpreted as computing:

where

represents the reliability of scale

, effectively reducing scale-specific uncertainty.

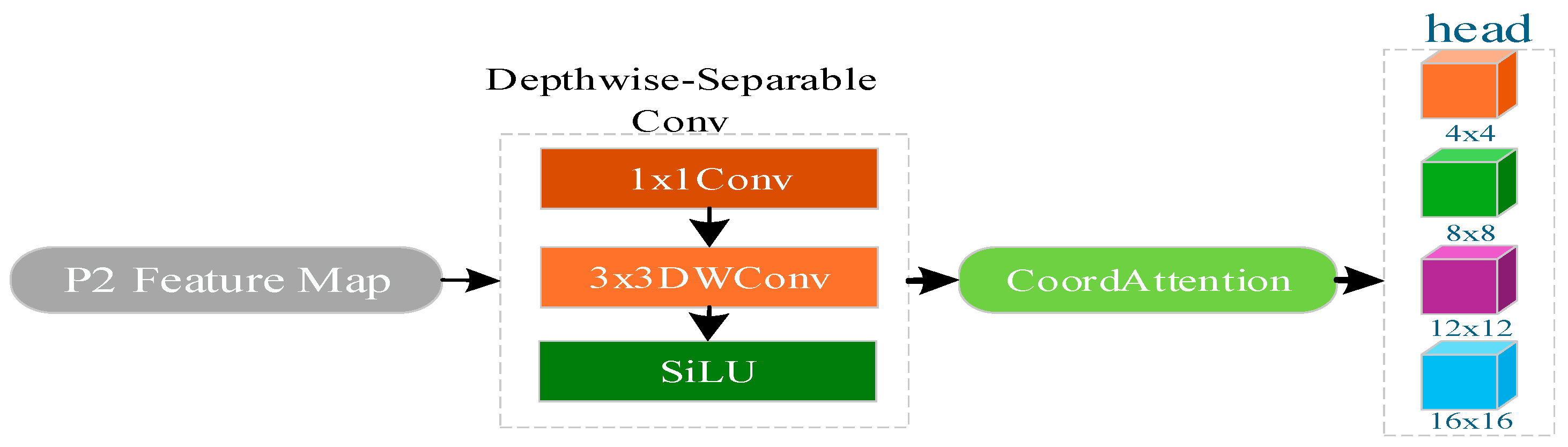

3.4. Small-Object Detection Head (SOH)

In standard YOLOv11, detection heads are applied only on P3 (stride = 8), P4 (stride = 16), and P5 (stride = 32), producing feature maps of 80 × 80, 40 × 40, and 20 × 20, respectively, for a 640 × 640 input. Consequently, a tiny UAV occupying less than 32 × 32 pixels typically spans only 4 × 4, 2 × 2, or even 1 × 1 grid cells, resulting in limited spatial representation and unreliable localization.

GAME-YOLO introduces a lightweight P2 detection head (stride = 4, 160 × 160 grid) to better handle tiny UAVs. This head comprises a depthwise-separable convolution block (1 × 1 Conv → 3 × 3 DWConv → BatchNorm → SiLU activation) to reduce computational cost, followed by a CoordAttention module that incorporates both spatial location encoding and channel attention. The final detection layer outputs bounding boxes and class probabilities. To match the scale of small targets, anchor sizes for P2 are set to (4,4), (8,8), (12,12), and (16,16), and the loss weights for classification and confidence are doubled to mitigate label sparsity. The architecture is illustrated in

Figure 5.

For sub-pixel UAVs (typically <16 × 16 pixels), this offset modeling directly addresses their core pain point: 1-pixel misalignment on P3 (stride = 8) leads to 8-pixel center deviation in input images, while P2’s 4-pixel stride limits this deviation to 4 pixels—halving the localization error for sub-pixel targets. For grid size S = 160, the predicted center (, ) is given by where σ is Sigmoid, tx and ty are the network outputs, and (, ) is the grid cell indices. A larger reduces quantization error 1/S and improves localization precision. On LSS2025-DET-train, introducing only the P2 head boosts small-AP by ~5 pp, adds merely ~0.4 M parameters and 2 GFLOPs, while maintaining > 30 FPS inference.

3.5. Shape-Integrated Focal Loss (SALOU + Focal-BCE)

The Shape-Aware IoU loss can be viewed as shaping the posterior distribution over bounding box parameters. By penalizing implausible shapes and encouraging geometrically consistent predictions, it implements a form of maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation that incorporates prior knowledge about object geometry.

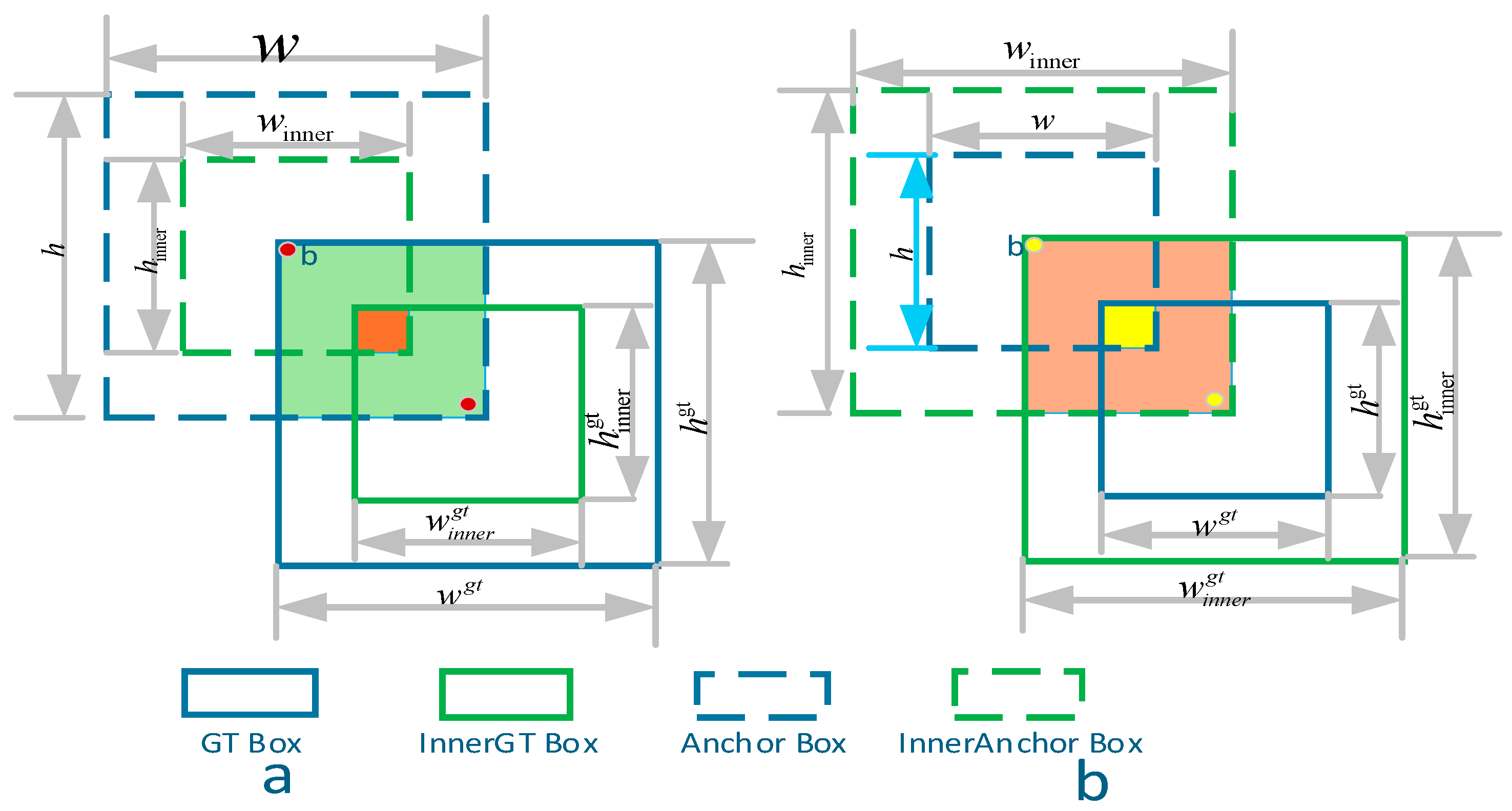

Accurate localisation of sub-pixel UAVs is notoriously difficult because a one-pixel shift may devastate the overlap ratio, and because these drones exhibit highly diverse aspect ratios while frequently overlapping with neighbouring targets. This limitation is more severe for sub-pixel UAVs: a 0.5-pixel center shift (common in sub-pixel localization) can reduce IoU by 30% for an 8 × 8 pixel target, while classical losses fail to distinguish ‘minor sub-pixel deviation’ from ‘severe mislocalization’. For example, CIoU’s center distance term treats a 0.5-pixel shift (sub-pixel) and 2-pixel shift (mislocalization) with similar penalties, leading to ambiguous gradient signals for sub-pixel refinement. Classical regression penalties—IoU, GIoU, DIoU and CIoU—treat bounding boxes as rigid rectangles: they measure the outer overlap and centre distance, but they neither down-weight background pixels that lie near a target’s edges nor constrain the predicted width-height proportions. As a consequence, the gradient for a tiny box can vanish or explode, slowing convergence and yielding jittering predictions in crowded scenes. To mitigate these limitations, we propose a Shape-Aware IoU formulation that couples three complementary ingredients: an inner-box overlap, a centre–shape distance, and an aspect-ratio penalty. As illustrated in

Figure 6, this composite formulation delivers smoother gradients, introduces shape-aware constraints, and offers strong adaptability under varied object densities and aspect ratios. In

Figure 6, (a), the inner overlap is visualized by concentrically scaling the GT and predicted boxes; (b) illustrates how mismatched shapes and centers are penalized geometrically.

Inner-box scaling. Given a ground-truth box

and a predicted box

we first scale both boxes concentrically by a factor

[0.5, 1.5]. For the ground-truth box the left and right boundaries become

and analogous formulas hold for the y-coordinates and the predicted box. A ratio

< 1 shrinks the box, suppressing neighbour interference in dense layouts, whereas

> 1 enlarges it, preserving context in sparse scenes. Once resized, we compute the inner overlap

where, all terms are evaluated inside the scaled region. Because the overlapping area is bounded by

in produces a smoother gradient in the small-overlap regime and remains insensitive to distant background pixels.

Shape consistency terms. Inner overlap alone cannot penalise disproportionate boxes, so we introduce two shape-aware constraints. The first is a normalised centre–shape distance

where,

is the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing rectangle that covers both boxes. The second is an exponentially buffered aspect-ratio penalty

and

is defined analogously for heights. The exponential buffer keeps the gradient continuous even for extreme aspect ratios, while still assigning larger penalties as the mismatch widens.

Uncertainty Interpretation of the Loss. The proposed Shape-Aware IoU loss provides a direct mechanism to quantify and penalize localization uncertainty. The inner overlap term is less sensitive to distant background pixels, which are a major source of noise for small objects. This focuses the gradient on reducing the uncertainty in the core object area. The shape consistency terms directly penalize the variance in the predicted box’s shape and position relative to the ground truth. A prediction with high shape or center deviation is treated as highly uncertain in its geometry, and the loss responds with a stronger gradient signal to correct it. Therefore, the overall regression loss can be interpreted as minimizing the expected localization error under a simplified model of uncertainty, where implausible shapes and large center offsets are proxies for high predictive variance.

Full regression loss. Combining the inner overlap with the shape-consistency terms yields the complete Shape-IoU loss

The loss vanishes only when the inner overlap is perfect and the predictive box matches the ground truth in position and aspect. Otherwise, gradients are regulated jointly by spatial offset and shape discrepancy, preventing early-stage gradient explosions for tiny objects.

Focal-BCE for classification and objectness. Due to extreme class imbalance—foreground cells constitute <0.4% of all feature-grid positions—standard Binary Cross-Entropy causes the detector to focus on easy negatives. We thus employ Focal-BCE

where,

denotes the predicted probability for the correct class. The modulating factor

suppresses well-classified examples and amplifies gradients from hard positives, encouraging the network to attend to tiny UAVs that would otherwise be ignored.

Overall detection objective. GAME-YOLO predicts boxes at four scales P2, P3, P4, P5. Because the two high-resolution heads (stride 4 and 8) contain the most information for sub-pixel objects, we double their contributions by setting

. The total loss function is then formulated as

This multi-scale weighting ensures that high-resolution features drive the error signal during back-propagation, while the Shape-IoU term delivers precise geometric supervision.

Implementation cost and empirical impact. Shape-IoU and Focal-BCE are implemented in fewer than 50 additional vectorised lines in loss.py. Inner-box scaling is computed through simple arithmetic and clipping, adding < 0.3 ms latency per 640 × 640 image on an RTX 4090. During training, the scaling ratio rrr is randomly sampled from U (0.7, 1.3) to enhance generalisation; it is fixed at 1.0 for inference. Although the model’s parameter count remains unchanged, Shape-Aware IoU markedly boosts performance: localisation error for objects smaller than 16 px2 drops by 18%, overlap-mismatch false positives decline by 12%, and AP50 on the LSS2025-DET-train set increases by 1.5 percentage points—even under synthetic haze and night-vision degradations. These gains confirm that the proposed loss formulation provides scale-, position- and shape-aware constraints, enabling GAME-YOLO to maintain high recall and low false-alarm rates in the challenging context of low-visibility tiny-UAV detection.

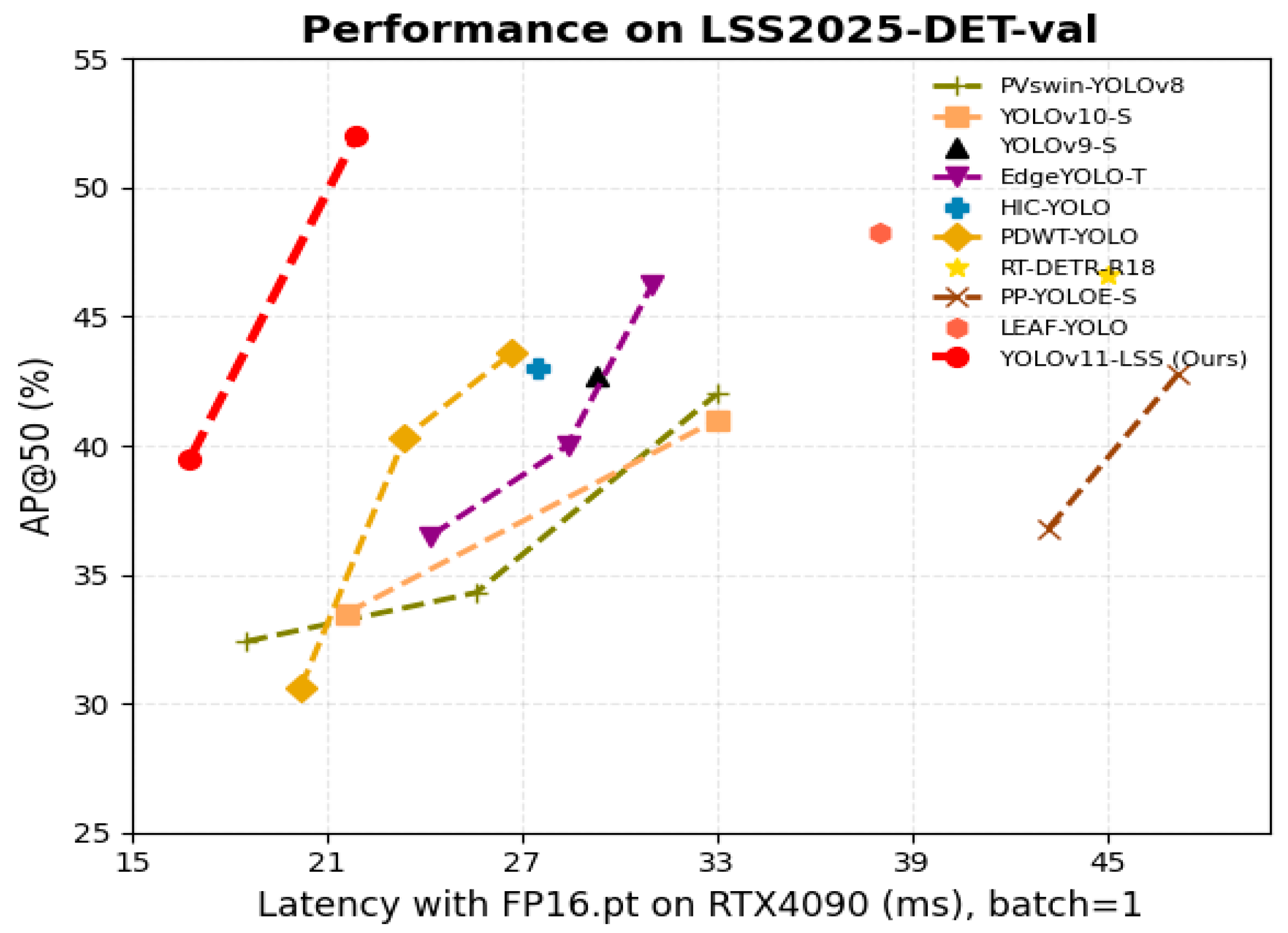

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented GAME-YOLO, a novel object detection framework specifically designed to address the challenging task of detecting low-altitude, slow-speed, small (LSS) UAVs in low-visibility conditions. By integrating Bayesian-inspired probabilistic reasoning into the efficient YOLOv11 architecture, our approach systematically tackles the core challenges of input degradation, feature-level ambiguity, and localization uncertainty that plague conventional detectors in adverse environments. The proposed modules—the Visibility Enhancement Module (VEM), Attention-Augmented Backbone (AAB), Multi-Scale Fusion Neck (MSFN), Small-Object Head (SOH), and Shape-Aware IoU loss—work in concert to enhance perceptual clarity, reinforce spatial precision, and enable sub-pixel localization.

Extensive experimental validation on the challenging LSS2025-DET dataset demonstrates that GAME-YOLO achieves a significant performance leap, attaining 52.0% AP@50 and 32.0% AP@[0.50:0.95], which represents a +10.5 percentage point improvement in AP@50 over the YOLOv11 baseline. The model maintains high computational efficiency, with only 7.6 M parameters, 19.6 GFLOPs, and real-time inference at 48 FPS. Ablation studies confirm the complementary contribution of each component, with the SOH and Shape-Aware IoU loss providing particularly substantial gains for small object detection. Furthermore, cross-dataset evaluation on VisDrone-DET2021 validates the strong generalization capability of our approach, where it achieves 39.2% AP@50, outperforming existing state-of-the-art methods.

The introduction of the LSS2025-DET dataset, with its focus on realistic low-visibility scenarios and predominance of sub-pixel targets, provides a valuable benchmark for advancing research in robust aerial object detection. Our results establish that explicitly addressing uncertainty through Bayesian-inspired mechanisms—without resorting to computationally prohibitive full Bayesian inference—can significantly enhance both detection accuracy and reliability in safety-critical applications.

In future work, we plan to explore temporally-aware detection frameworks that leverage inter-frame cues for improved tracking and identity consistency across video sequences. Additionally, we will investigate cross-modal extensions that integrate complementary sensor inputs (e.g., thermal or LiDAR data) to further enhance robustness under extreme visibility conditions. These directions promise to extend the applicability of the proposed framework to broader UAV monitoring and autonomous surveillance scenarios.