Multi-Function Computation over a Directed Acyclic Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

- In Section 2, we formally present the model of network multi-function computation, and define the network multi-function computing codes and the rate region.

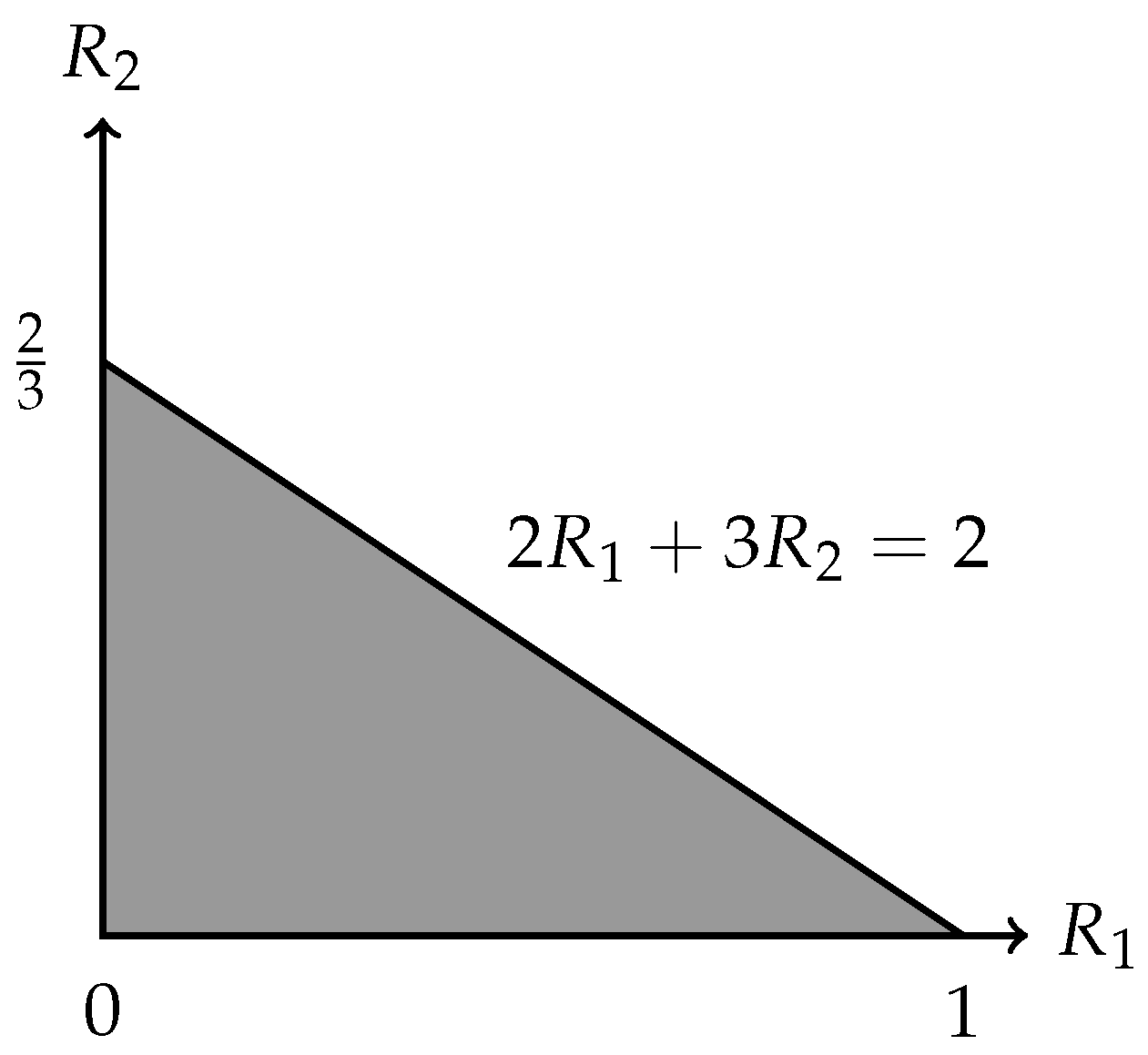

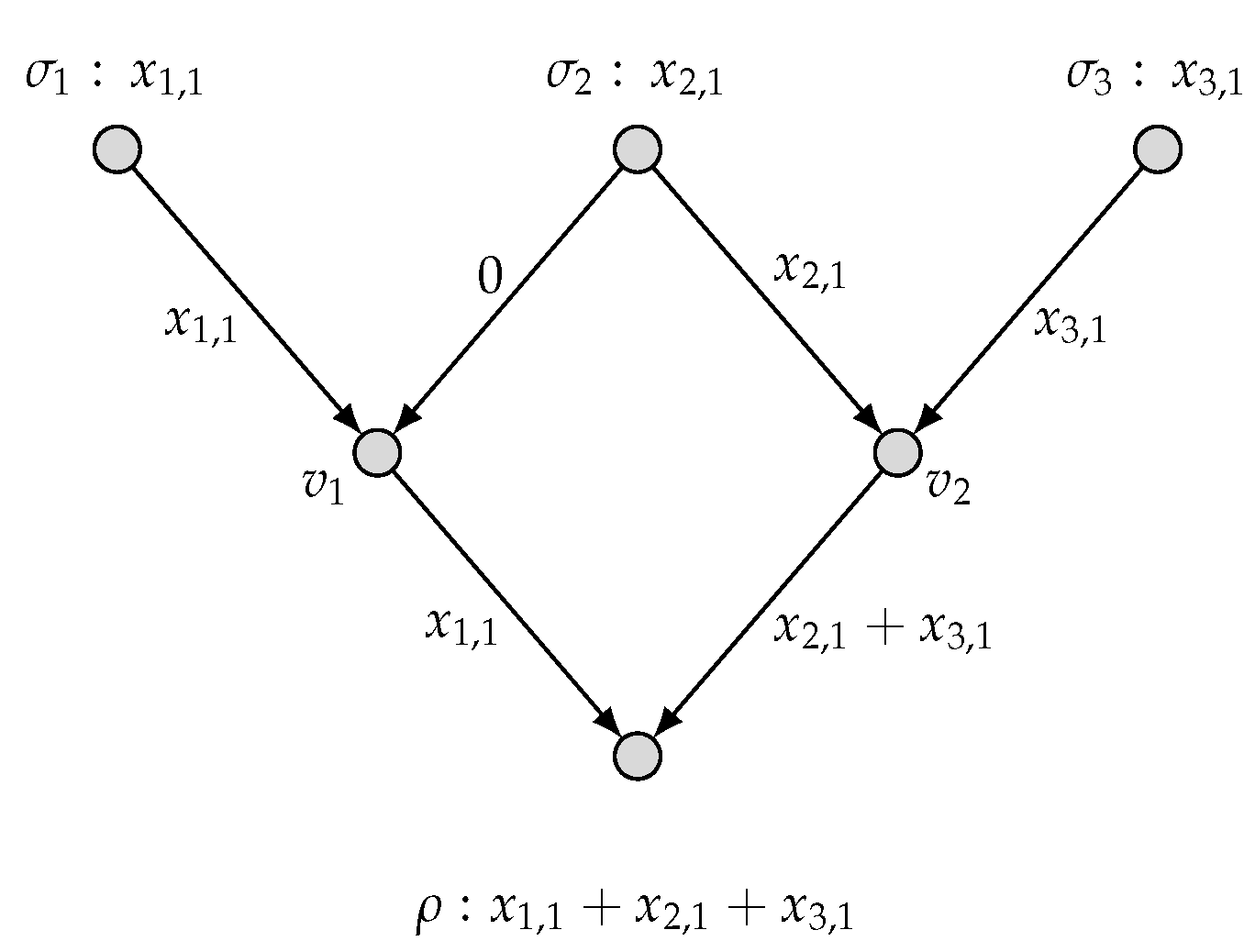

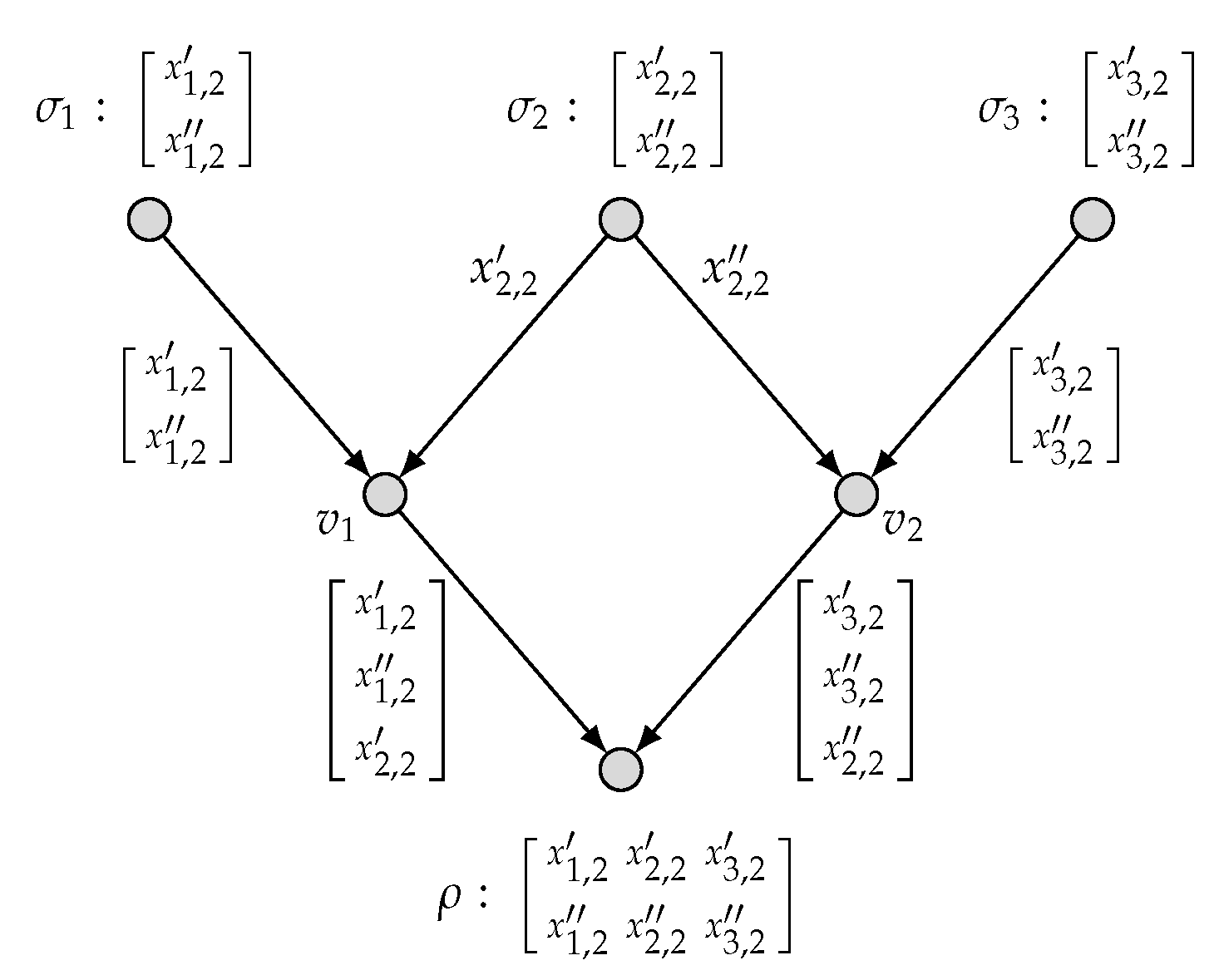

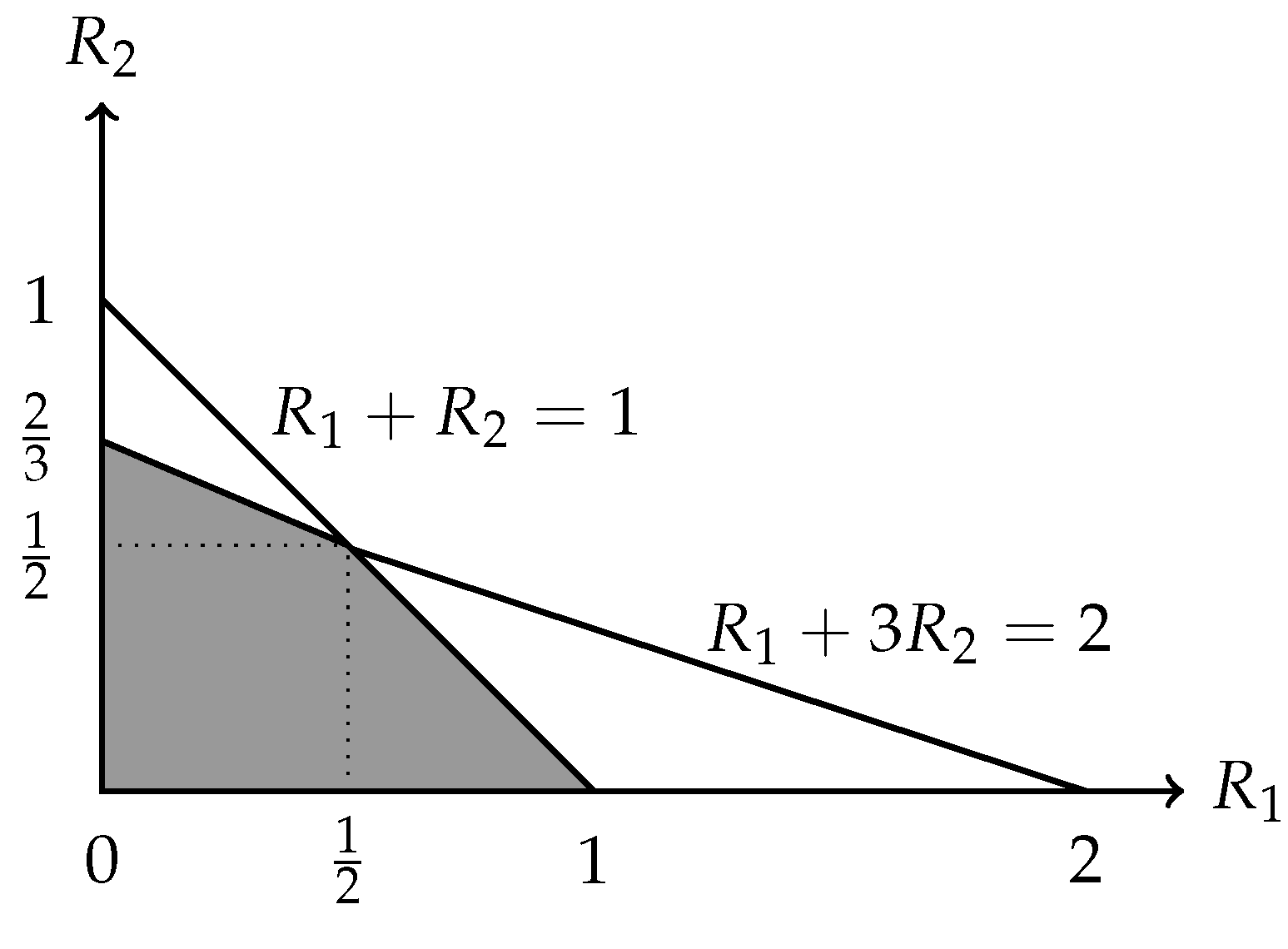

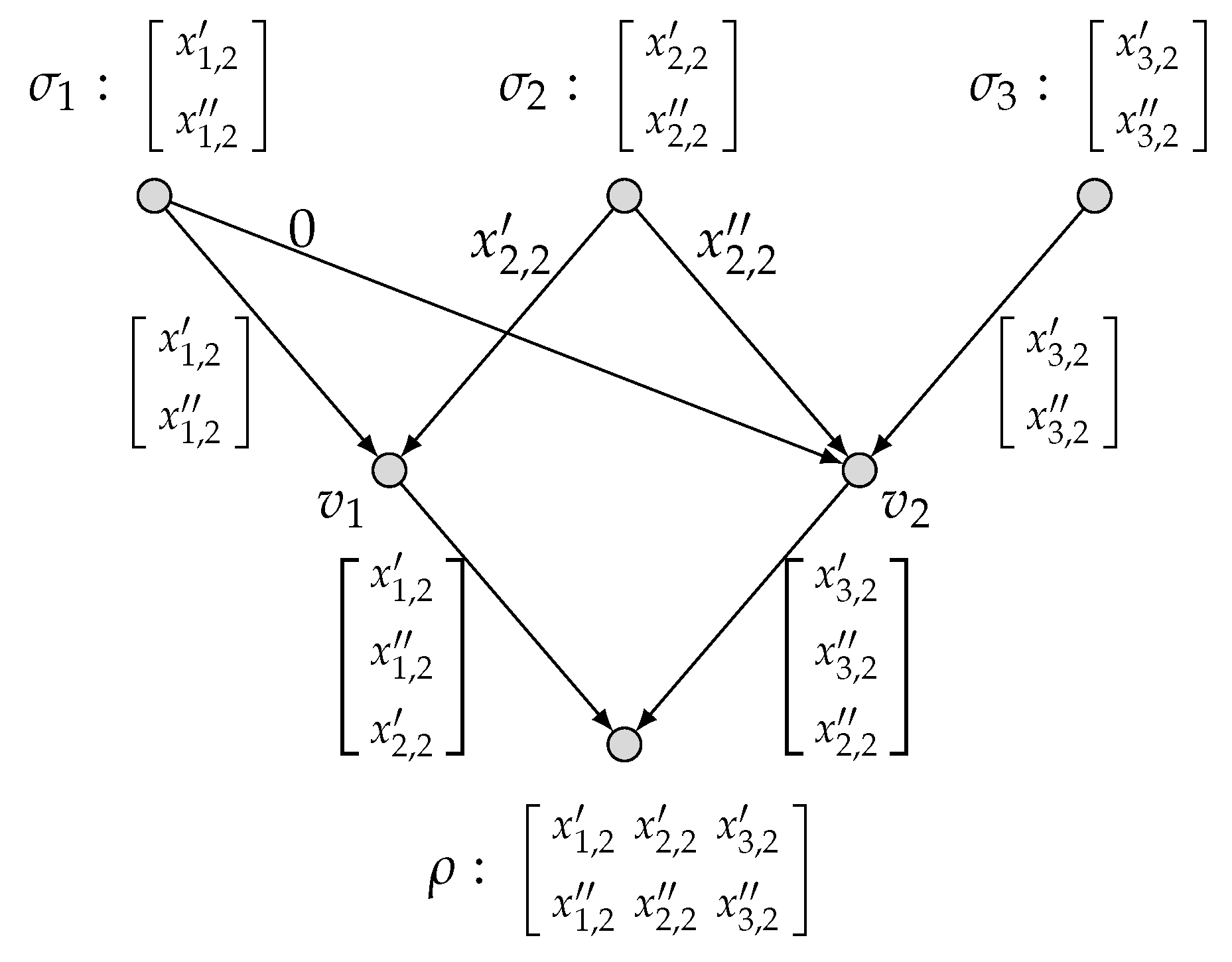

- In Section 3, we prove an outer bound on the rate region by developing the approach of the cut-set strong partition introduced by Guang et al. [4], which is applicable to arbitrary network topologies and arbitrary vector-linear functions. We also illustrate that the obtained outer bound is tight for a typical model of computing two vector-linear functions over the diamond network.

- In Section 4, we compare network multi-function computation and network function computation. We first establish the relationship between the network multi-function computation rate region and the network function computation rate region. By this relationship, we show that the best known outer bound in [4] on the network function computation rate region can induce an outer bound on the network multi-function computation rate region. However, this induced outer bound is not as tight as our outer bound. Further, we show that the best known outer bound in [4] on the rate region for computing an arbitrary vector-linear function over an arbitrary network is a straightforward consequence of our outer bound.

- Finally, we conclude in Section 5 with a summary of our results.

2. Preliminaries

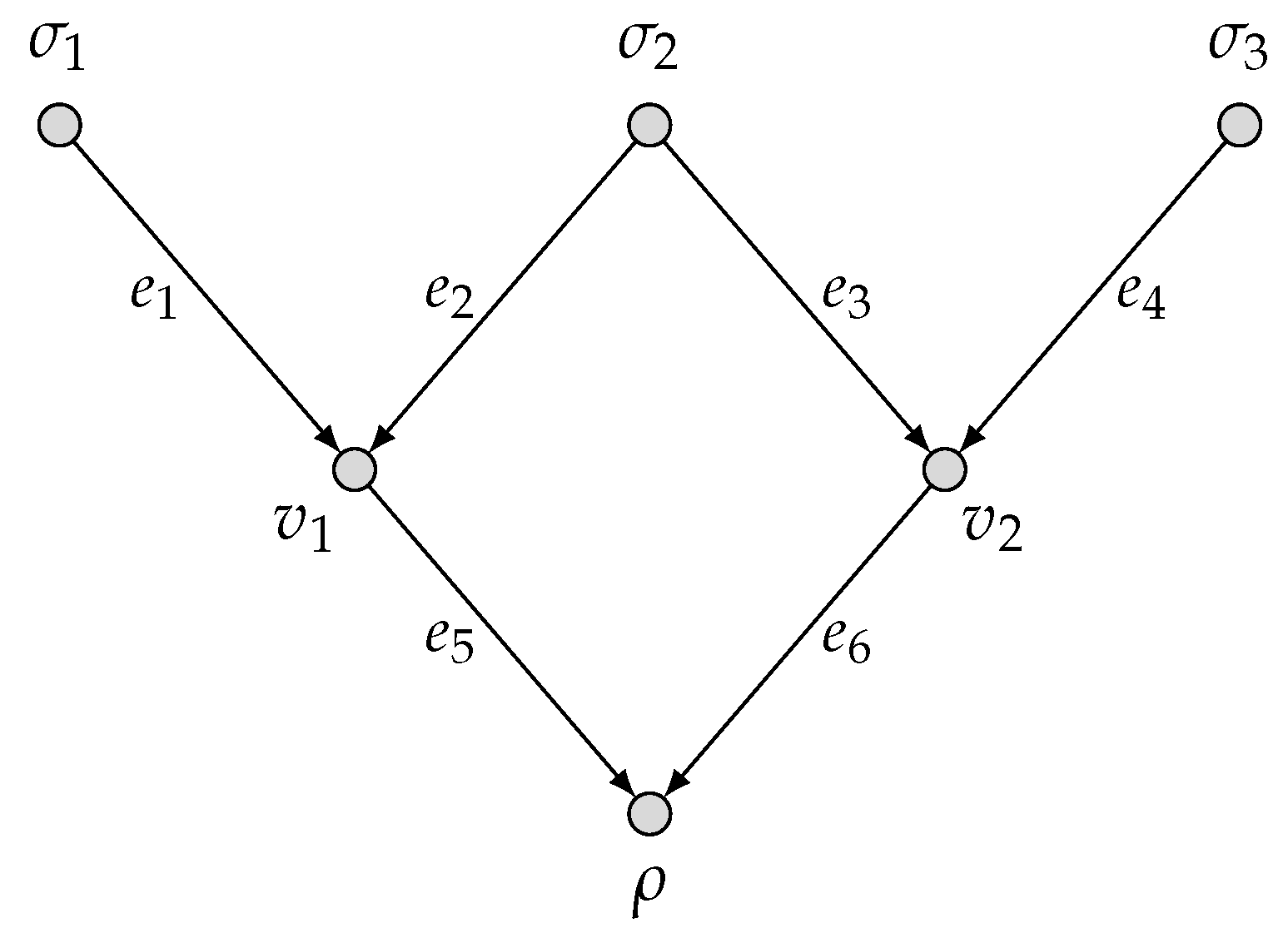

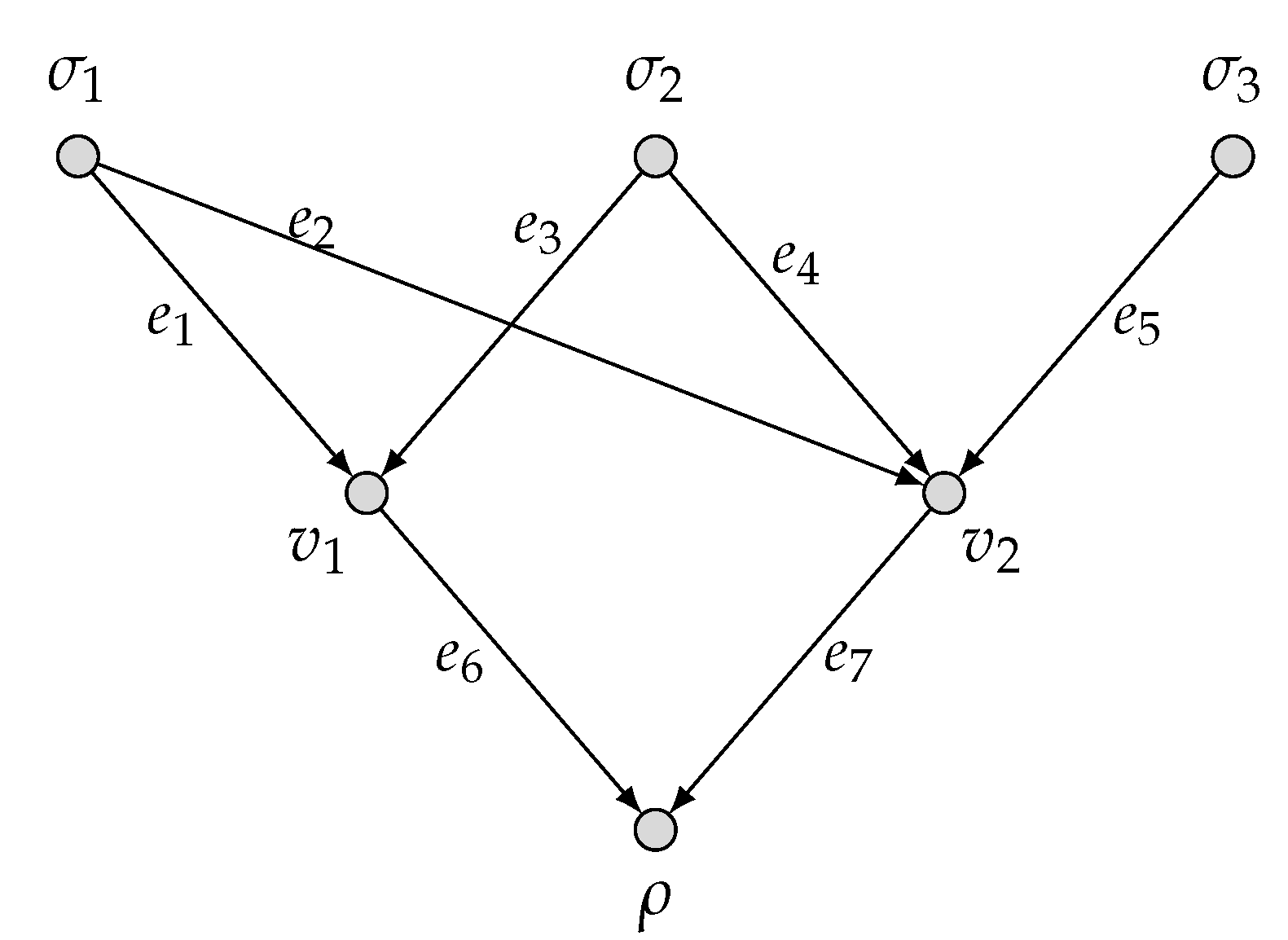

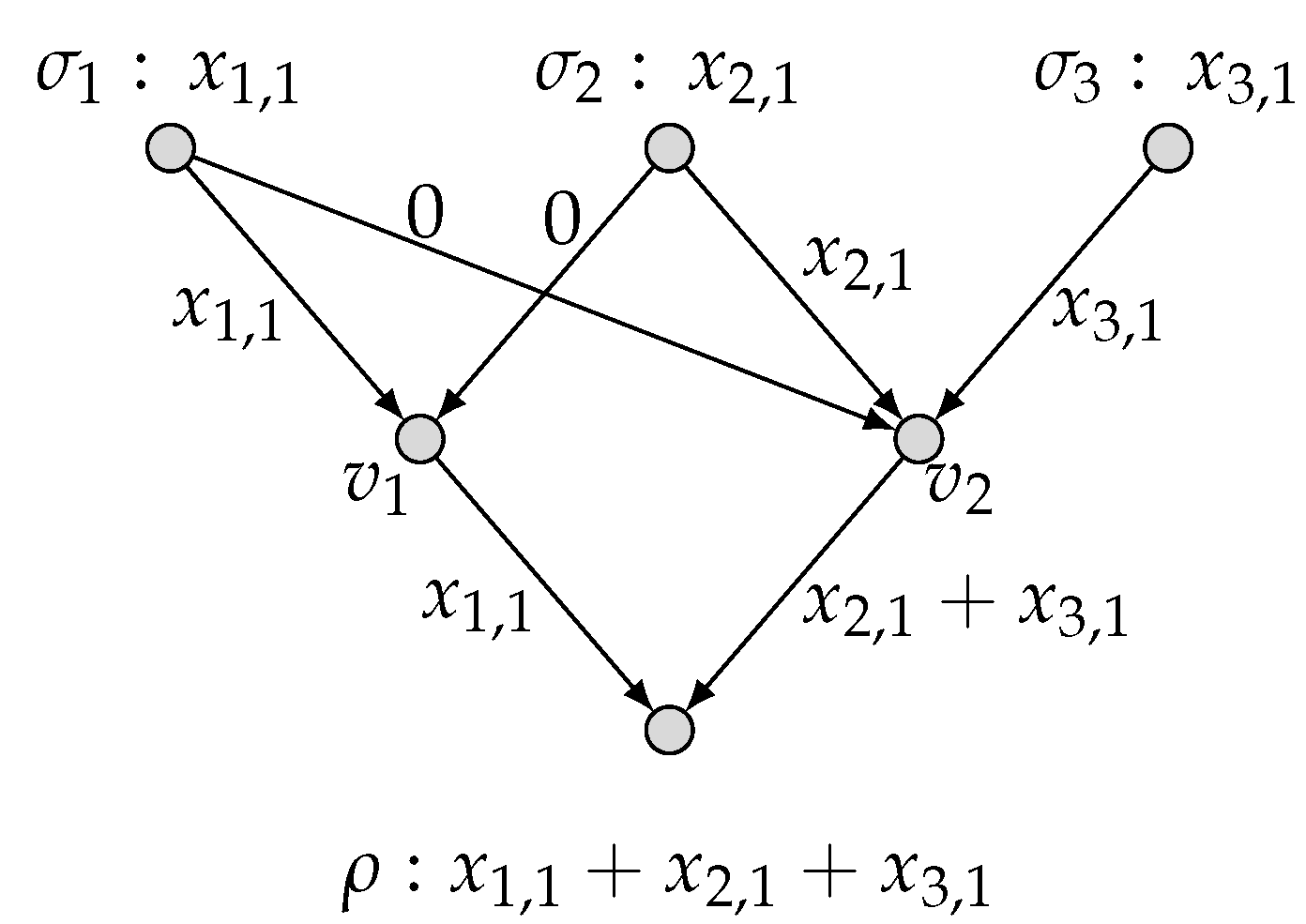

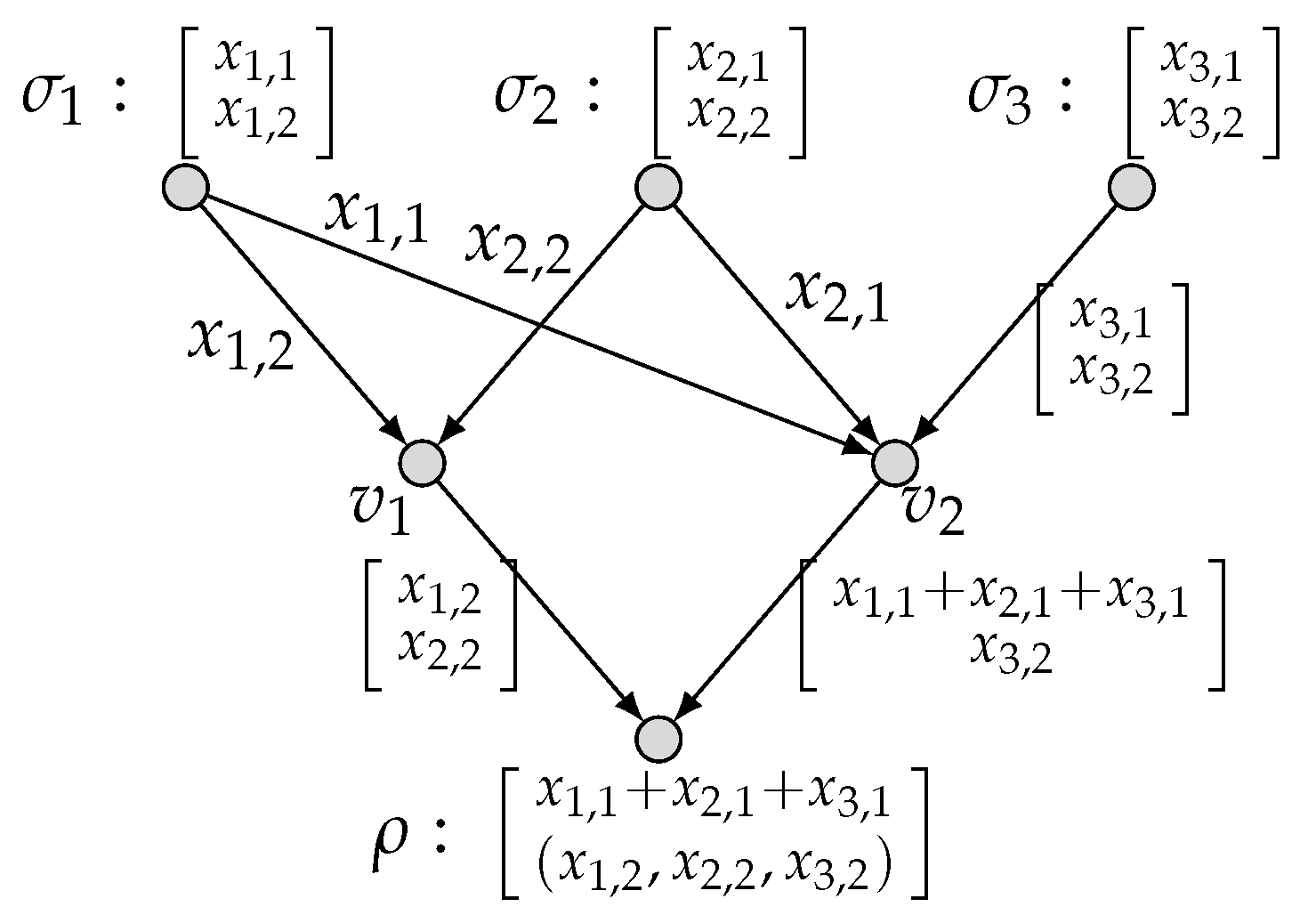

2.1. Model of Network Multi-Function Computation

2.2. Network Multi-Function Computing Coding

- a local encoding function for each edgewhere

- t decoding functions with at the sink node

- With the encoding mechanism as described, the local encoding functions derive recursively the symbols transmitted over all edges e, denoted by , which can be considered as vectors in . Specifically, can be written aswhere and for an edge set . We call the global encoding function for an edge e.

3. Outer Bound on the Rate Region

Proof of Theorem 1

4. Comparison on Network Function Computation

- We first consider the cut set and its trivial strong partition . We can see that , and thusBy Theorem 1, we have

- In the following, we consider the global cut set and its trivial strong partition . We can see that , and thusBy Theorem 1, we also have

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proof of Lemma 1

Appendix B. Proof of Lemma 2

Appendix C. Proof of Lemma 3

Appendix D. Proof of Theorem 2

References

- Appuswamy, R.; Franceschetti, M.; Karamchandani, N.; Zeger, K. Network coding for computing: Cut-set bounds. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2011, 57, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Tan, Z.; Yang, S.; Guang, X. Comments on cut-set bounds on network function computation. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 6454–6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuswamy, R.; Franceschetti, M. Computing linear functions by linear coding over networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 60, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Yeung, R.W.; Yang, S.; Li, C. Improved upper bound on the network function computing capacity. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2019, 65, 3790–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuswamy, R.; Franceschetti, M.; Karamchandani, N.; Zeger, K. Linear codes, target function classes, and network computing capacity. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 5741–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, A.; Langberg, M. Communicating the sum of sources over a network. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.; Dey, B. On network coding for sum-networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2012, 58, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, B.; Das, N. Sum-networks: Min-cut = 2 does not guarantee solvability. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2013, 17, 2144–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Ramamoorthy, A. Sum-networks from incidence structures: Construction and capacity analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 3461–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowshik, H.; Kumar, P. Optimal function computation in directed and undirected graphs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2012, 58, 3407–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, A.; Kumar, P. Computing and communicating functions over sensor networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2005, 23, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, Y. Computing vector-linear functions on diamond network. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 26, 1519–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guang, X.; Yang, S.; Niu, X.; Bai, B. Computation of binary arithmetic sum over an asymmetric diamond network. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Inf. Theory 2024, 5, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Zhang, R. Zero-error distributed compression of binary arithmetic sum. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2024, 70, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Ramamoorthy, A. On computation rates for arithmetic sum. In Proceedings of the 2016 the IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Barcelona, Spain, 10–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, A.; Ramamoorthy, A. Zero-error function computation on a directed acyclic network. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW), Guangzhou, China, 25–29 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feizi, S.; Médard, M. Multi-functional compression with side information. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 30 November–4 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, S.; Viswanath, P. Multi-session function computation and multicasting in undirected graphs. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günlü, O.; Bloch, M.; Schaefer, R.F. Private remote sources for secure multi-function computation. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2022, 68, 6826–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kruglik, S.; Kiah, H.M. Coded computation of multiple functions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Information Theory Workshop, Sundsvall, Sweden, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Kruglik, S.; Kiah, H.M. Verifiable coded computation of multiple functions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 8009–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, D.; Deylam Salehi, M.; Serbetci, B.; Elia, P. Multi-server multi-function distributed computation. Entropy 2024, 26, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Feng, X.; Zhang, L.; Qian, L.; Wu, Y. Multi-server multi-user multi-task computation offloading for mobile edge computing networks. Sensors 2019, 19, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.; Shen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Multi-function radar signal sorting based on complex network. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, J.; Georgiopoulos, M. Generative neural networks for multi-task life-long learning. Comput. J. 2014, 57, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, H.; Kobayashi, I. A study on developmental artificial neural networks that integrate multiple functions using variational autoencoder. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soft Computing and Machine Intelligence, Mexico City, Mexico, 25–26 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malak, D.; Salehi, M.R.D.; Serbetci, B.; Elia, P. Multi-functional distributed computing. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Monticello, IL, USA, 24–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, D.; Guang, X. Multi-Function Computation over a Directed Acyclic Network. Entropy 2025, 27, 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121225

Sun X, Zhang R, Li D, Guang X. Multi-Function Computation over a Directed Acyclic Network. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121225

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiufang, Ruze Zhang, Dan Li, and Xuan Guang. 2025. "Multi-Function Computation over a Directed Acyclic Network" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121225

APA StyleSun, X., Zhang, R., Li, D., & Guang, X. (2025). Multi-Function Computation over a Directed Acyclic Network. Entropy, 27(12), 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121225