Explainable Structured Pruning of BERT via Mutual Information

Abstract

1. Introduction

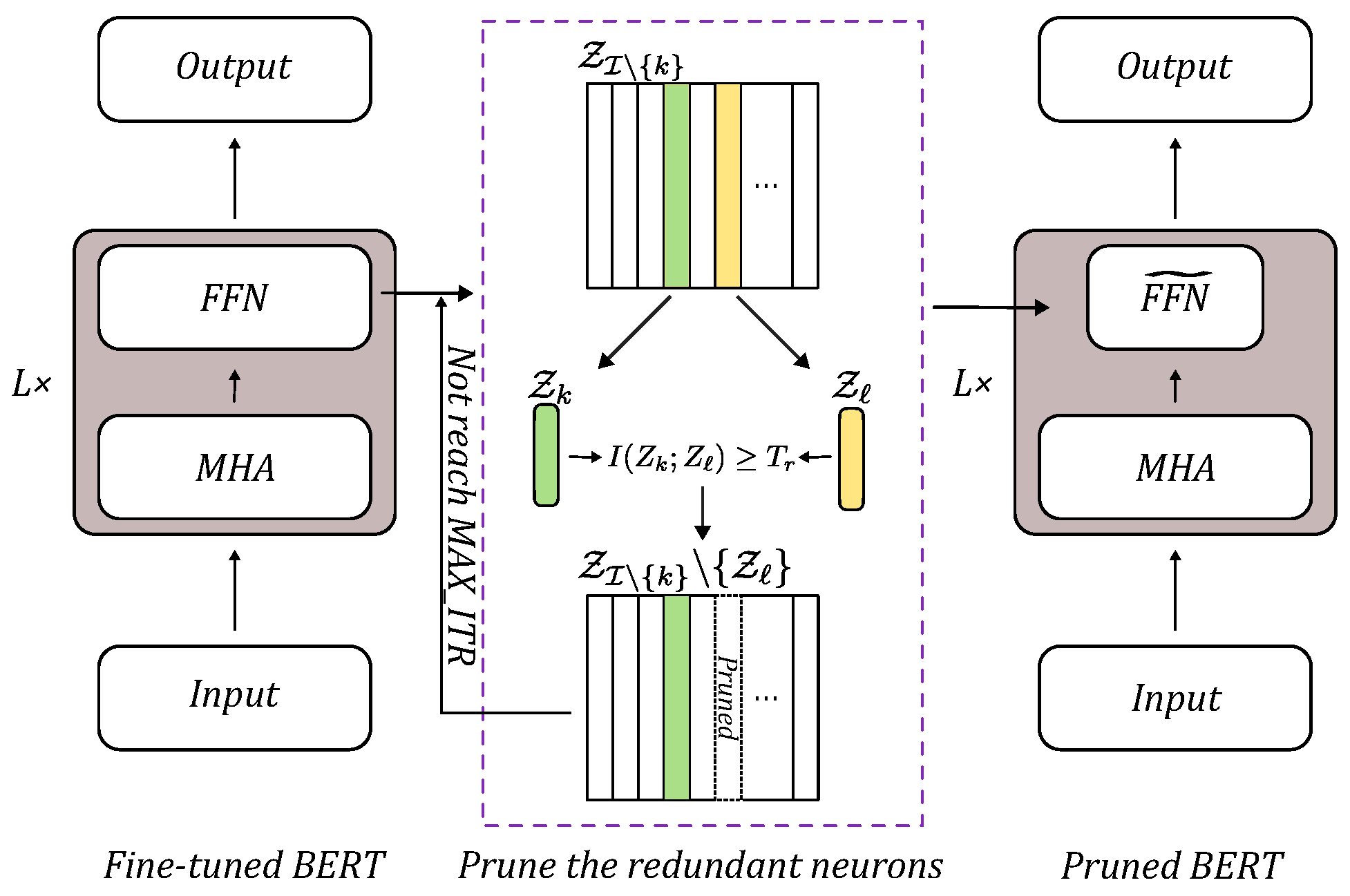

- We propose a novel MI-based structured scheme targeting BERT’s FFN layers, achieving high compression with minimal accuracy loss for on-device deployment.

- The proposed method is considered an unsupervised approach, which needs no label information to decide the pruning strategy. That provides a lower burden when moving to large-scale models, which may suffer from the labeled data-hungry problem.

- A mutual information estimation method tailored to deep representations is proposed, featuring a novel kernel bandwidth estimator to compute MI between hidden nodes.

- We construct visualizations of the compression process to intuitively reveal changes in the representations and predictive behavior before and after pruning, thereby enhancing understanding and trust in the method’s effectiveness.

- The method is superior to other unsupervised pruning methods. It also shows some competitiveness when compared to some of the supervised approaches.

2. Related Work

2.1. Structured Pruning

2.2. Mutual Information Estimation

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Preliminaries

3.1.1. Notations

3.1.2. Information-Theoretic Basis

- MI: MI quantifies the dependence between two random variables X and Y. It is formally defined using the standard Shannon entropy asIn the context of model pruning, the goal is to assess the shared information between a neuron’s output (X) and the model’s output or target labels (Y).

- Rényi -Order Entropy: To facilitate a robust non-parametric estimation of MI, we leverage the Rényi -order entropy (). Unlike Shannon entropy, Rényi entropy is particularly useful when probability density functions are difficult to estimate directly. It is defined aswhere is the probability mass function for a discrete variable X, and with .

3.2. Framework

3.3. Redundancy as a Feature Selection Criterion

| Algorithm 1 The algorithm of an alternative strategy to select a subset of features that has low mutual information between pairwise features |

| Require: : The no. of remaining features after the alternative pruning strategy : Maximum allowed feature overlapping : The maximum number of iterations Ensure: : The resulting feature set after the pruning strategy

|

3.3.1. Clustering Strategy as a Scale-Up Option

3.3.2. Subsidiary Condition

3.4. Estimation Method of Mutual Information Between Hidden Neurons

3.4.1. Matrix-Based Rényi -Order Entropy

3.4.2. Matrix-Based Rényi -Order Joint Entropy

3.4.3. MI Expressed Through Matrix-Based Rényi’s -Order Entropy

3.4.4. Estimation Method of the Kernel Width Parameter of a Hidden Neuron

4. Results of the Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

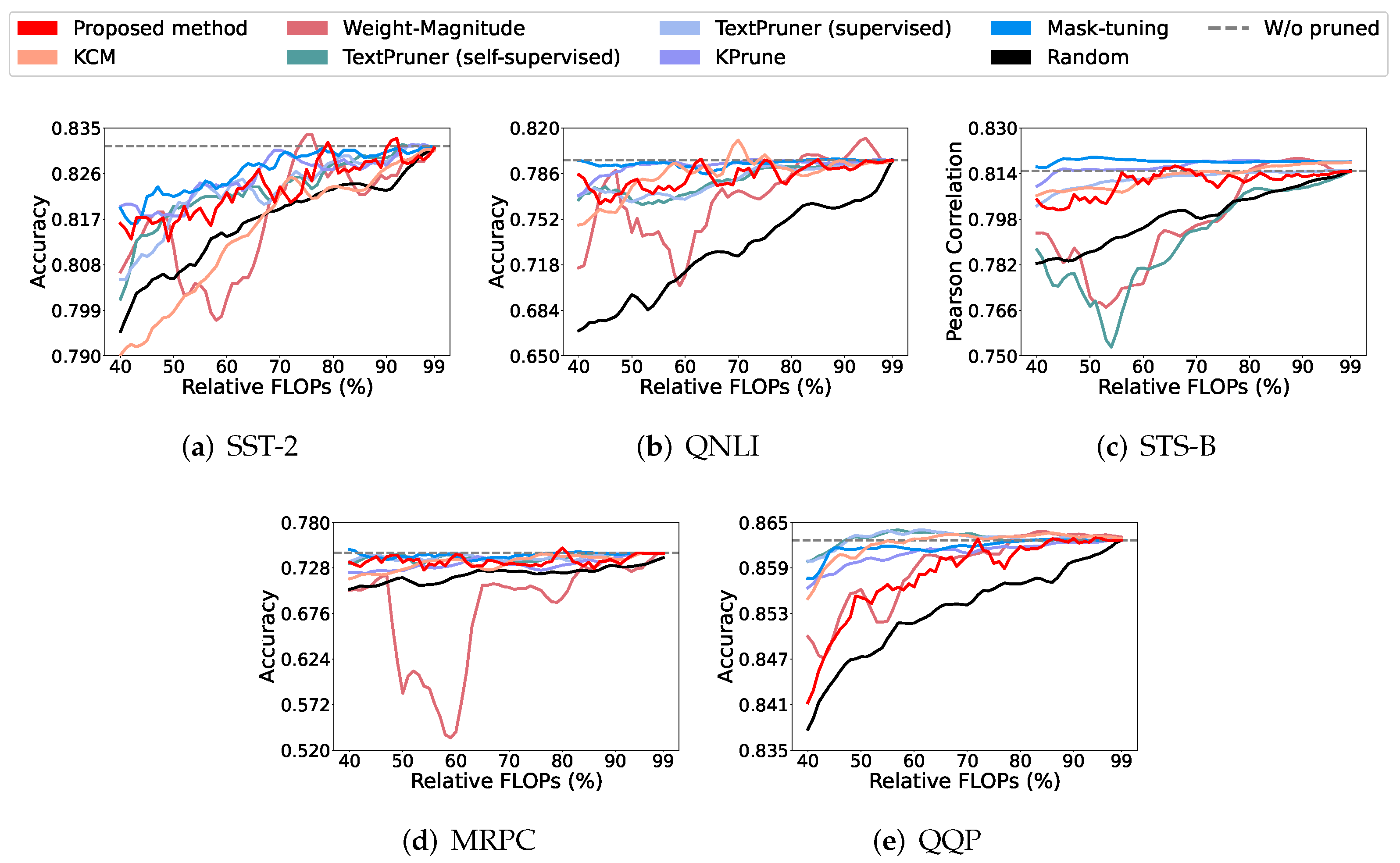

4.2. The Results of Model Pruning

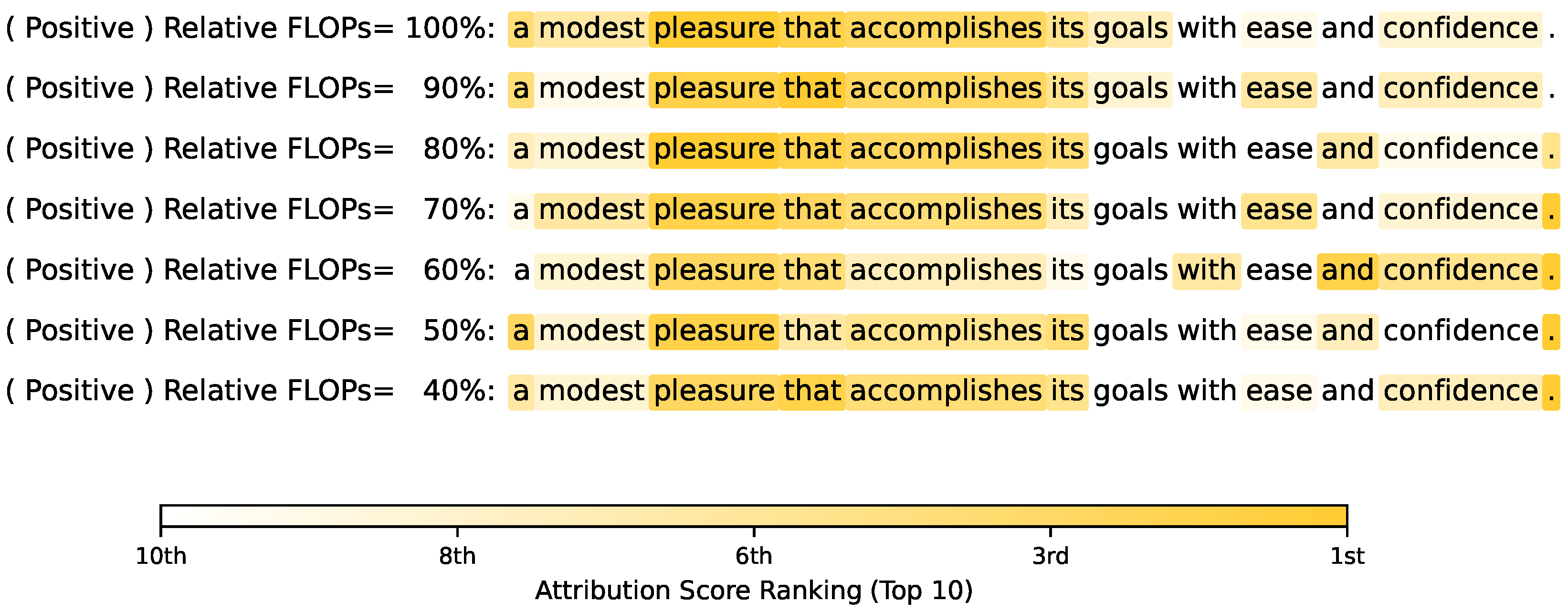

4.3. Explanation of the Network Pruning

4.4. Mutual Information Between Hidden Neurons Estimation

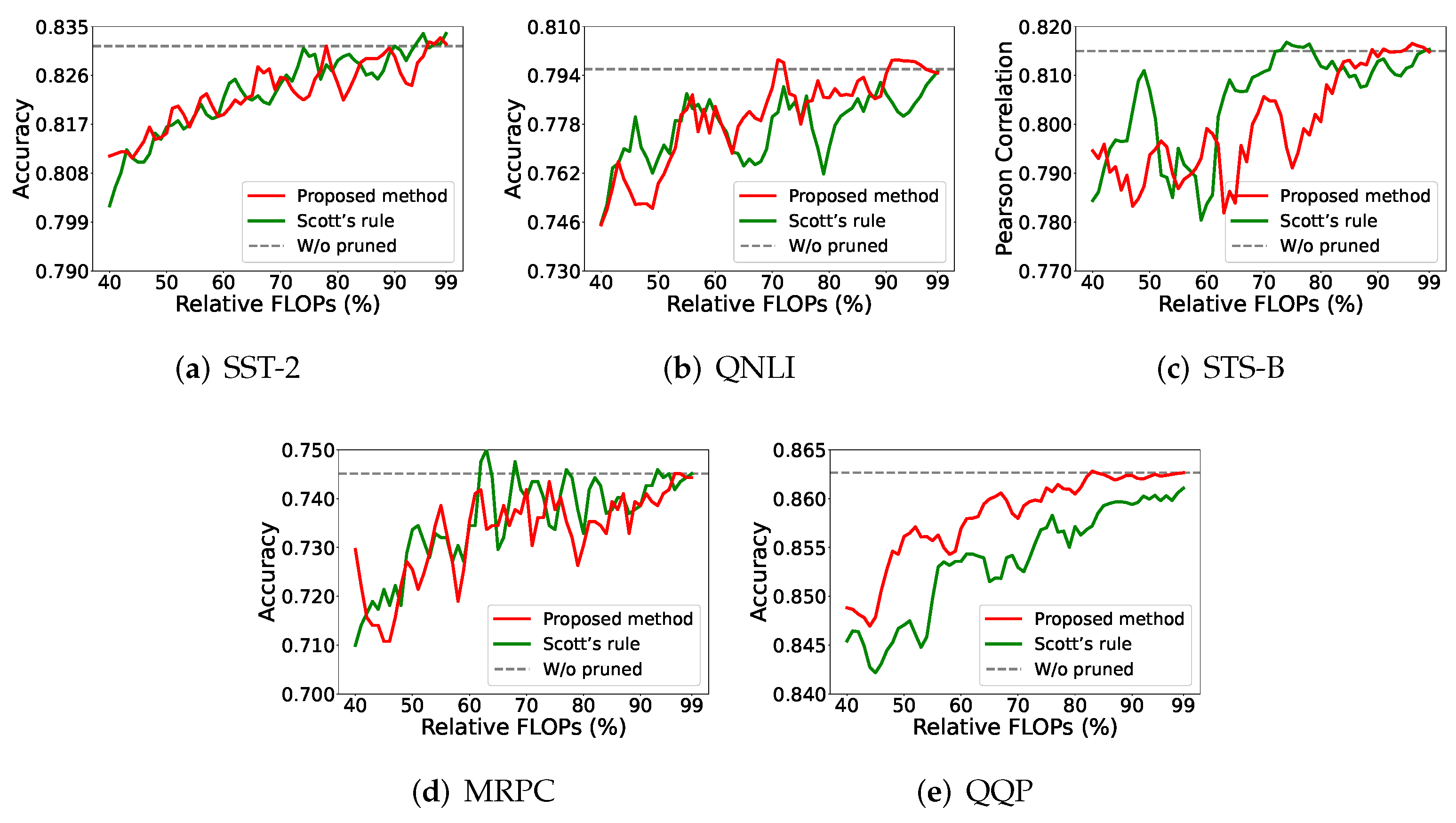

4.5. Ablation Study

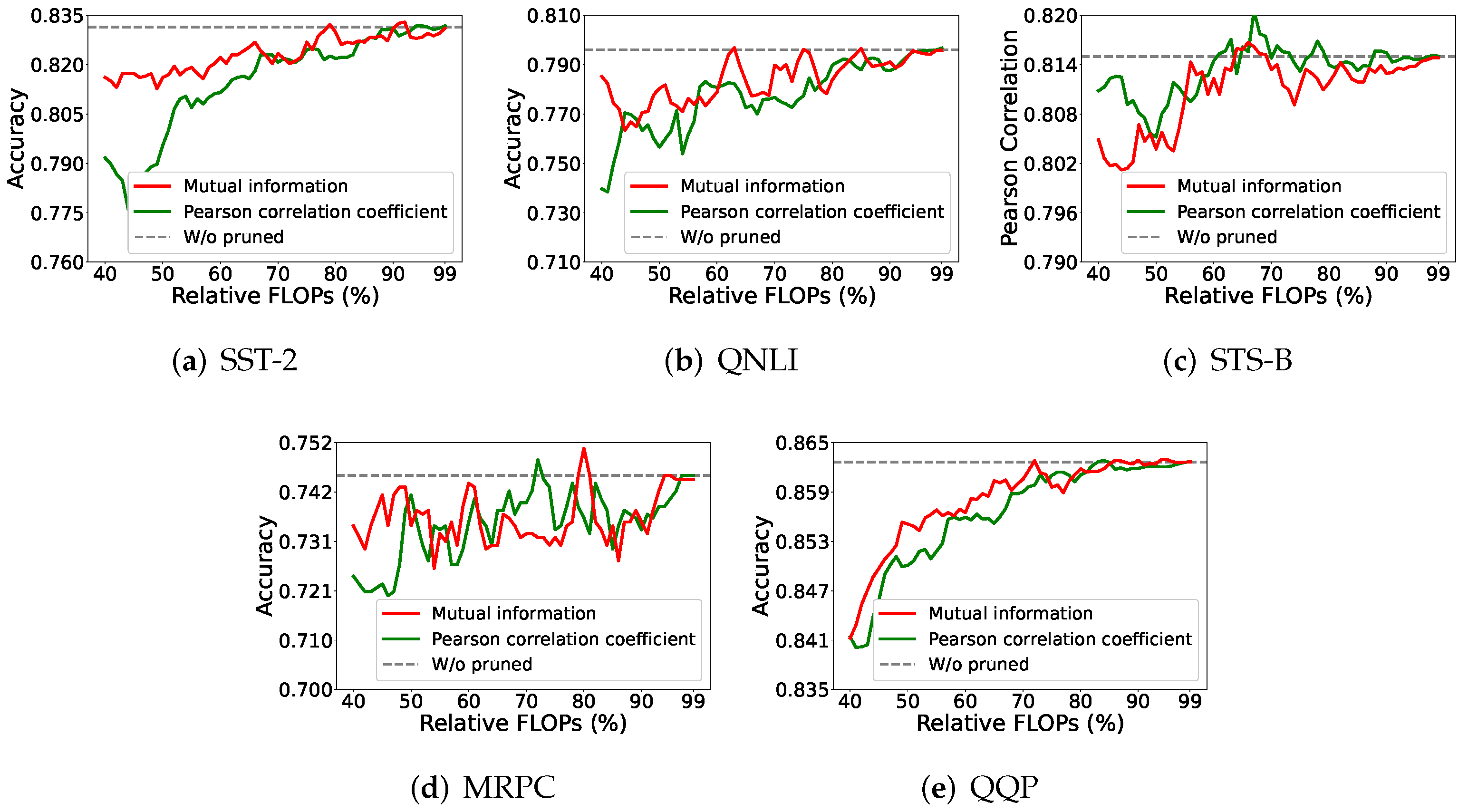

4.5.1. Mutual Information vs. Pearson Correlation Coefficient

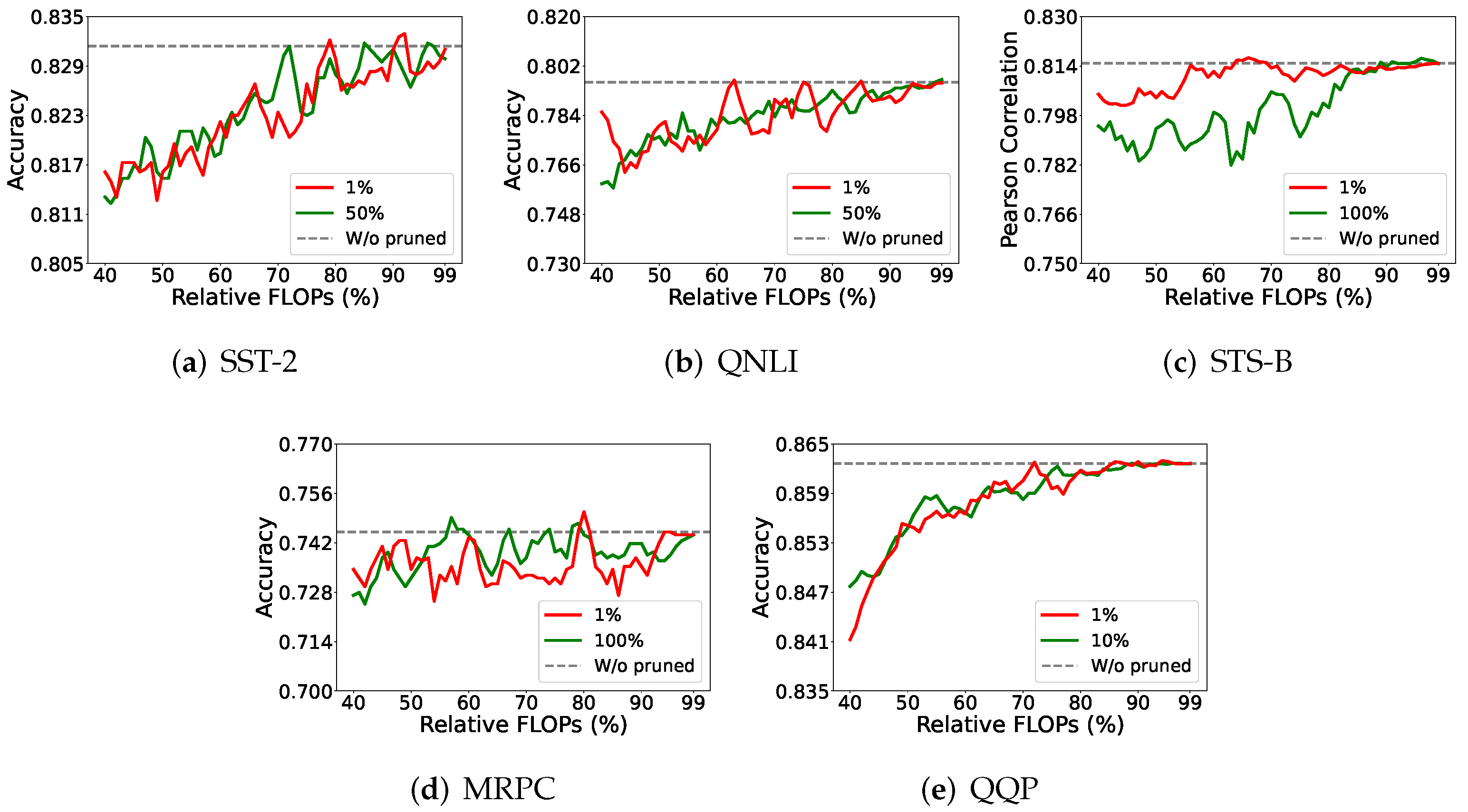

4.5.2. Data Samples for Mutual Information Estimation

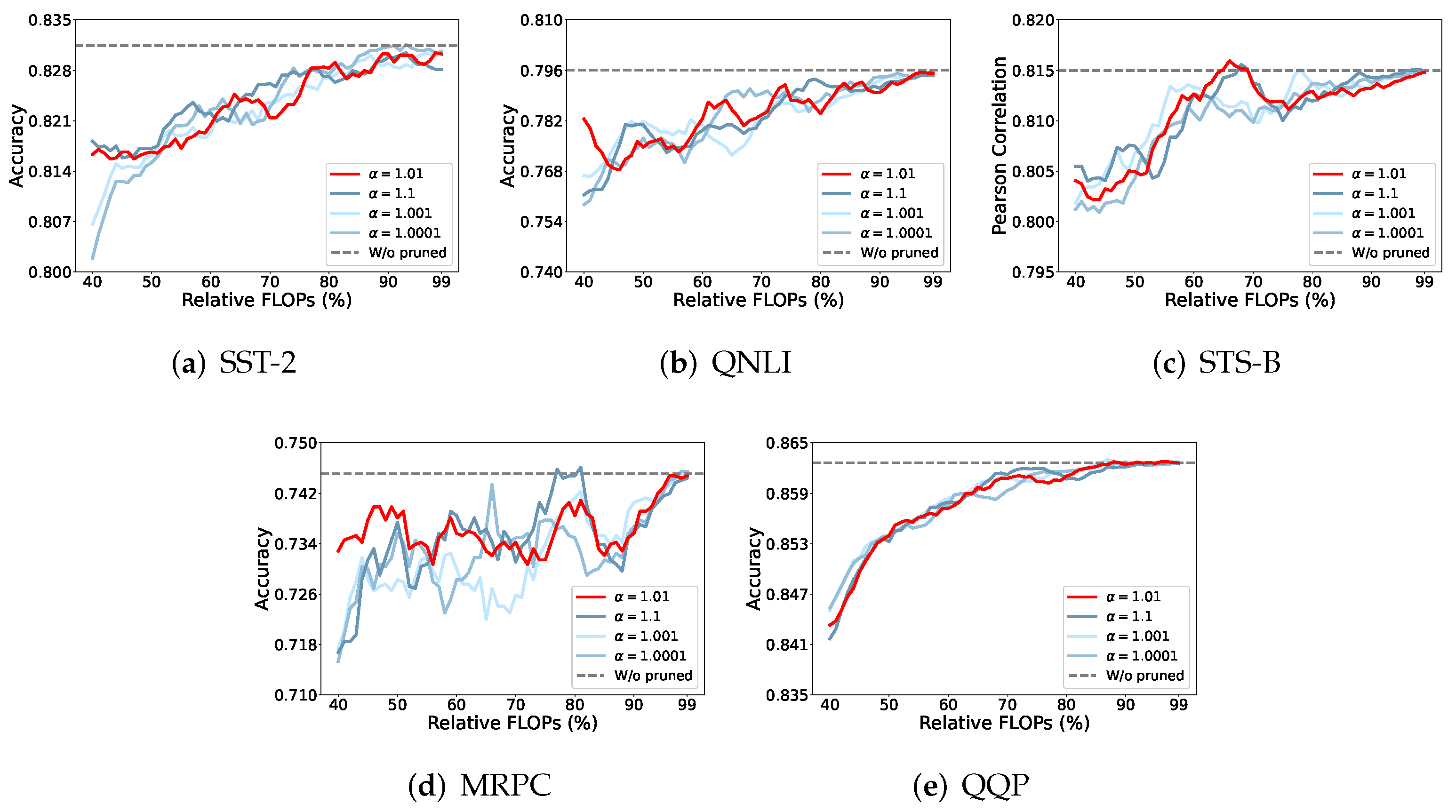

4.5.3. Different for Matrix-Based Rényi -Order Entropy Estimation

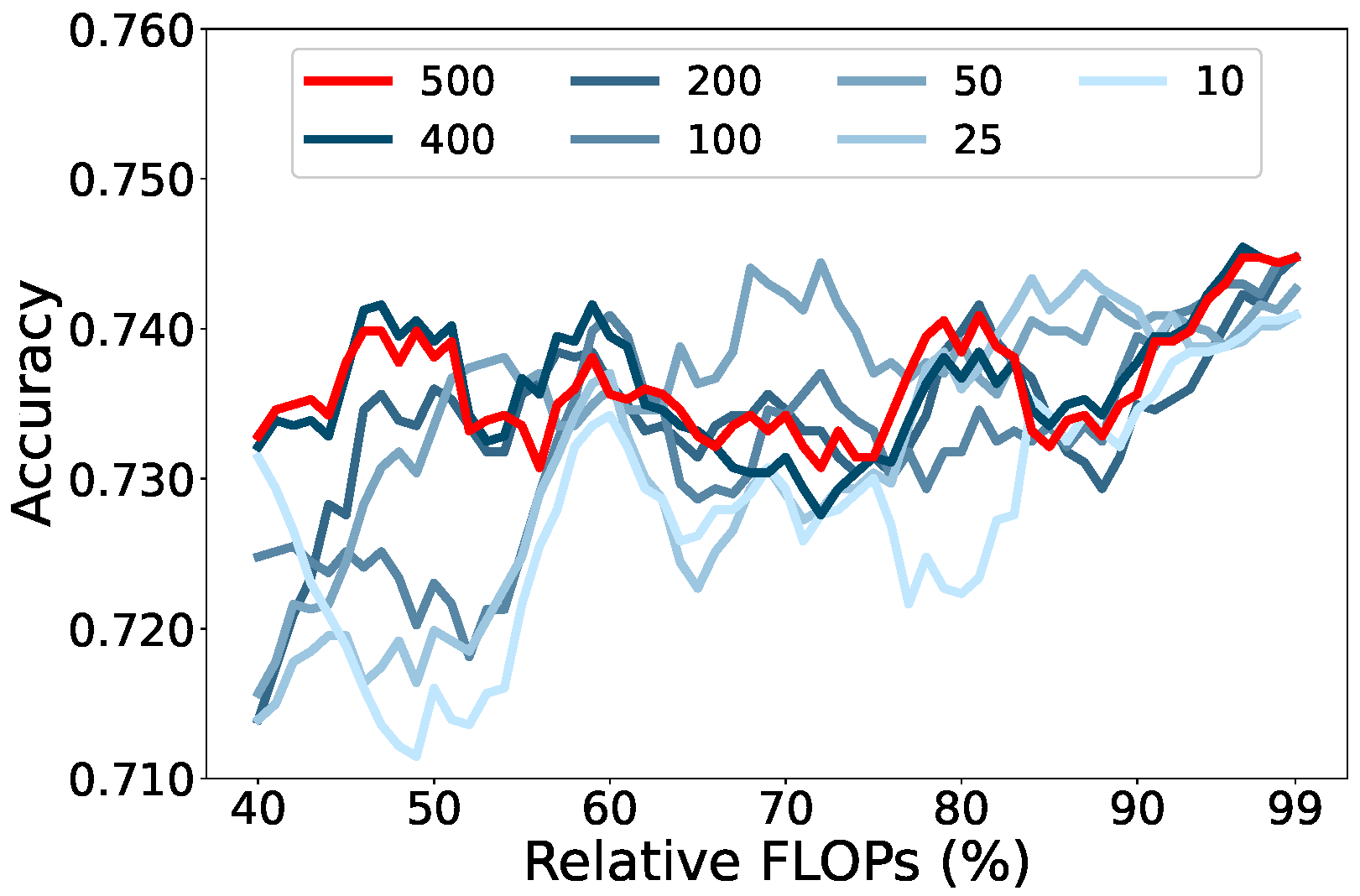

4.5.4. Sample Number for MDS

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal brain damage. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 November 1989; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Kadav, A.; Durdanovic, I.; Samet, H.; Graf, H.P. Pruning filters for efficient convnets. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.08710. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Fang, G.; Wang, X. LLM-Pruner: On the Structural Pruning of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 21702–21720. [Google Scholar]

- Frantar, E.; Alistarh, D. Massive language models can be accurately pruned in one-shot. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.; Mori, G. Similarity-preserving Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1365–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Huang, M. Knowledge Distillation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.08543. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Han, K.; Zhang, W.; Ma, S.; Gao, W. Post-training quantization for vision transformer. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 28092–28103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Oguz, B.; Zhao, C.; Chang, E.; Stock, P.; Mehdad, Y.; Shi, Y.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Chandra, V. LLM-QAT: Data-Free Quantization Aware Training for Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17888. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Meadowlark, P.; He, Y.; Lew, L.; Agrawal, S.; Rybakov, O. 4-bit conformer with native quantization aware training for speech recognition. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.15952. [Google Scholar]

- Povey, D.; Cheng, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Xu, H.; Yarmohammadi, M.; Khudanpur, S. Semi-orthogonal low-rank matrix factorization for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Hyderabad, India, 2–6 September 2018; pp. 3743–3747. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Yao, Z.; He, Y. ZeroQuant-FP: A Leap Forward in LLMs Post-Training W4A8 Quantization Using Floating-Point Formats. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09782. [Google Scholar]

- Blalock, D.; Gonzalez Ortiz, J.J.; Frankle, J.; Guttag, J. What is the state of neural network pruning? Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2020, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, W. A Survey on Model Compression for Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.07633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Shen, C.; Yang, Z.; Ou, L.; Yu, X.; Zhuang, B. Pruning Meets Low-Rank Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.18403. [Google Scholar]

- Nova, A.; Dai, H.; Schuurmans, D. Gradient-Free Structured Pruning with Unlabeled Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, P.; Chen, Y.; Lou, X.; Khan, M.A.; Yang, Y.; Sajjad, H.; Nakov, P.; Chen, D.; Winslett, M. Compressing large-scale transformer-based models: A case study on bert. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2021, 9, 1061–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickstrøm, K.; Løkse, S.; Kampffmeyer, M.; Yu, S.; Principe, J.; Jenssen, R. Information plane analysis of deep neural networks via matrix-based Renyi’s entropy and tensor kernels. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.11396. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; McAuley, J. A survey on model compression and acceleration for pretrained language models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 10566–10575. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksha, P.; Crespi, N. Explainable attention pruning: A metalearning-based approach. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 2505–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Pao, H.K. Interpretable deep model pruning. Neurocomputing 2025, 547, 130485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Song, H.J.; Pao, H.K. Large language model pruning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00030. [Google Scholar]

- Voita, E.; Talbot, D.; Moiseev, F.; Sennrich, R.; Titov, I. Analyzing multi-head self-attention: Specialized heads do the heavy lifting, the rest can be pruned. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.09418. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Li, G.; Cheng, J. EBERT: Efficient BERT inference with dynamic structured pruning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, Virtual, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 4814–4823. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, W.; Kim, S.; Mahoney, M.W.; Hassoun, J.; Keutzer, K.; Gholami, A. A fast post-training pruning framework for transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; Volume 35, pp. 24101–24116. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z. TextPruner: A Model Pruning Toolkit for Pre-Trained Language Models. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, H.; Kang, U. Accurate Retraining-free Pruning for Pretrained Encoder-based Language Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lagunas, F.; Charlaix, E.; Sanh, V.; Rush, A.M. Block pruning for faster transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.04838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Tishby, N. Opening the black box of deep neural networks via information. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.00810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvani, C.; Ghorai, M.; Dubey, S.R.; Basha, S.S. Hrel: Filter pruning based on high relevance between activation maps and class labels. Neural Netw. 2022, 147, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jo, J. Information flows of diverse autoencoders. Entropy 2021, 23, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.M.; Nemenman, I. Estimation of mutual information for real-valued data with error bars and controlled bias. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 100, 022404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraskov, A.; Stögbauer, H.; Grassberger, P. Estimating mutual information. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 066138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghazi, M.I.; Baratin, A.; Rajeshwar, S.; Ozair, S.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Hjelm, D. Mutual information neural estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Giraldo, L.G.; Rao, M.; Principe, J.C. Measures of entropy from data using infinitely divisible kernels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 61, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Giraldo, L.G.S.; Jenssen, R.; Principe, J.C. Multivariate Extension of Matrix-Based Rényi’s α-Order Entropy Functional. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W. Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice, and Visualization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.F.; Cox, M.A. Multidimensional Scaling; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cristianini, N.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Elisseeff, A.; Kandola, J. On kernel-target alignment. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3–8 December 2001; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Turc, I.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Well-read students learn better: On the importance of pre-training compact models. arXiv 1908, arXiv:1908.08962. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. GLUE: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07461. [Google Scholar]

- Socher, R.; Perelygin, A.; Wu, J.; Chuang, J.; Manning, C.D.; Ng, A.Y.; Potts, C. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 October 2013; pp. 1631–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Cer, D.; Diab, M.; Agirre, E.; Lopez-Gazpio, I.; Specia, L. Semeval-2017 task 1: Semantic textual similarity-multilingual and cross-lingual focused evaluation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.00055. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, B.; Brockett, C. Automatically Constructing a Corpus of Sentential Paraphrases. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Paraphrasing (IWP2005), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 15 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, O.; Elisha, Y.; Toib, Y.; Weill, J.; Koenigstein, N. Improving LLM Attributions with Randomized Path-Integration. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 9430–9446. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, O.; Béreux, N.; Baret, L.; Hashemi, V.; Lecue, F. Causal analysis for robust interpretability of neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 1–6 January 2024; pp. 4685–4694. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Core Principle | Primary Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binning-based [30] | Quantizes neuron output to estimate probability distributions. | Conceptually straightforward and easy to implement. | Sensitive to bin size; requires large sample sizes; struggles with high-dimensional non-linearities. |

| KSG [34] | Estimates MI based on k-nearest neighbor distances in high-dimensional space. | Applicable to a wide range of activation functions and density forms. | Highly sensitive to the choice of the number of neighbors (k). |

| MINE [35] | Uses an auxiliary neural network trained via gradient descent to estimate MI. | Scales linearly with dimensionality and sample size; excellent for high-dimensional data. | Slow convergence speed; highly sensitive to the auxiliary network’s architecture. |

| Rényi -Order [19] | Estimates MI via the kernel width parameter (), avoiding direct probability estimation. | Does not require explicit probability density estimation; computationally efficient. | Critical reliance on estimation; existing methods often focus on the entire layer, not individual neurons. |

| Tasks | Datasets | Training | Validation | Test | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-sentence | SST-2 | 67,350 | 873 | 1821 | Accuracy |

| Inference | QNLI | 104,743 | 5463 | 5461 | Accuracy |

| Similarity and paraphrase | STS-B | 5749 | 1379 | 1377 | Pearson correlation (r) Spearmen correlation () |

| MRPC | 3668 | 408 | 1725 | F1/Accuracy | |

| QQP | 363,870 | 40,431 | 390,965 | F1/Accuracy |

| Methods | S/U /Self-S | Relative FLOPs | SST-2 Acc | STS-B r/ | MRPC Acc/F1 | QQP Acc/F1 | QNLI Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BERT-tiny (Original) | 100% | 83.2 | 74.3/73.6 | 81.1/71.1 | 62.2/83.4 | 81.5 | |

| TextPruner [27] | S | 40% | 80.8 | 72.9/70.5 | 81.3/70.7 | 62.7/85.3 | 78.7 |

| Mask-tuning [26] | S | 40% | 81.7 | 73.7/70.9 | 80.7/69.6 | 61.8/85.3 | 65.0 |

| Kprune [28] | S | 40% | 83.1 | 74.4/72.3 | 81.0/70.1 | 61.8/84.2 | 77.5 |

| TextPruner [27] | Self-S | 40% | 81.8 | 70.3/68.7 | 80.8/70.0 | 62.8/84.9 | 76.2 |

| Random | U | 40% | 80.7 | 71.0/69.4 | 80.8/68.7 | 59.1/84.4 | 67.2 |

| Weight-Magnitude [3] | U | 40% | 81.8 | 71.4/69.6 | 80.8/68.5 | 61.2/83.9 | 67.7 |

| KCM [17] | U | 40% | 78.8 | 72.6/70.3 | 81.1/69.8 | 61.9/84.0 | 74.5 |

| Proposed method | U | 40% | 82.6 | 72.1/69.2 | 80.9/69.4 | 61.2/84.3 | 77.2 |

| Accuracy Under Specific Relative FLOPs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | S/U/Self-S | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% |

| (original) | 93.57 | ||||||

| TextPruner | S | 63.99 | 83.60 | 87.04 | 88.30 | 92.20 | 92.88 |

| MaskTuning | S | 71.44 | 84.28 | 89.10 | 91.51 | 91.97 | 92.77 |

| KPrune | S | 50.33 | 49.08 | 49.54 | 50.57 | 51.61 | 51.49 |

| KPrune * | S | 88.30 | 89.68 | 90.83 | 92.78 | 92.55 | 92.78 |

| TextPruner | SSL | 62.84 | 84.17 | 84.97 | 90.36 | 92.08 | 92.43 |

| KCM | U | 52.86 | 74.19 | 83.48 | 88.07 | 91.85 | 91.97 |

| Proposed method | U | 65.25 | 76.14 | 75.34 | 84.97 | 91.05 | 91.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Song, H.-J.; Zhao, Q. Explainable Structured Pruning of BERT via Mutual Information. Entropy 2025, 27, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121224

Huang H, Song H-J, Zhao Q. Explainable Structured Pruning of BERT via Mutual Information. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121224

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Hanjuan, Hao-Jia Song, and Qiling Zhao. 2025. "Explainable Structured Pruning of BERT via Mutual Information" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121224

APA StyleHuang, H., Song, H.-J., & Zhao, Q. (2025). Explainable Structured Pruning of BERT via Mutual Information. Entropy, 27(12), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121224