AFMNet: A Dual-Domain Collaborative Network with Frequency Prior Guidance for Low-Light Image Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose AFMNet, the first framework that decomposes low-light image enhancement into synergistic frequency prior estimation and spatial domain refinement. It learns a physically interpretable amplitude modulation prior to actively guide feature reconstruction, resolving the fundamental trade-off between global illumination consistency and local detail preservation.

- We innovatively design the Multi-Scale Amplitude Estimator (MSAE), which generates pixel-level, content-adaptive amplitude maps to overcome the limitations of static modulation. This module reframes illumination enhancement as a data-driven spectral regression task, enabling scene-specific compensation and significantly improved generalization under non-uniform or multi-source lighting conditions.

- We propose the first attention mechanism that injects a learnable spectral prior into feature modulation for global energy-aware enhancement, and the first feed-forward design that applies learnable complex-valued filters within local patches for structure-preserving, band-selective refinement—together enabling adaptive dual-domain collaboration.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Methods

2.2. Deep Learning Methods

2.3. Entropy-Guided and Information-Theoretic Methods

2.4. Frequency Domain-Based Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. Multi-Scale Amplitude Estimator

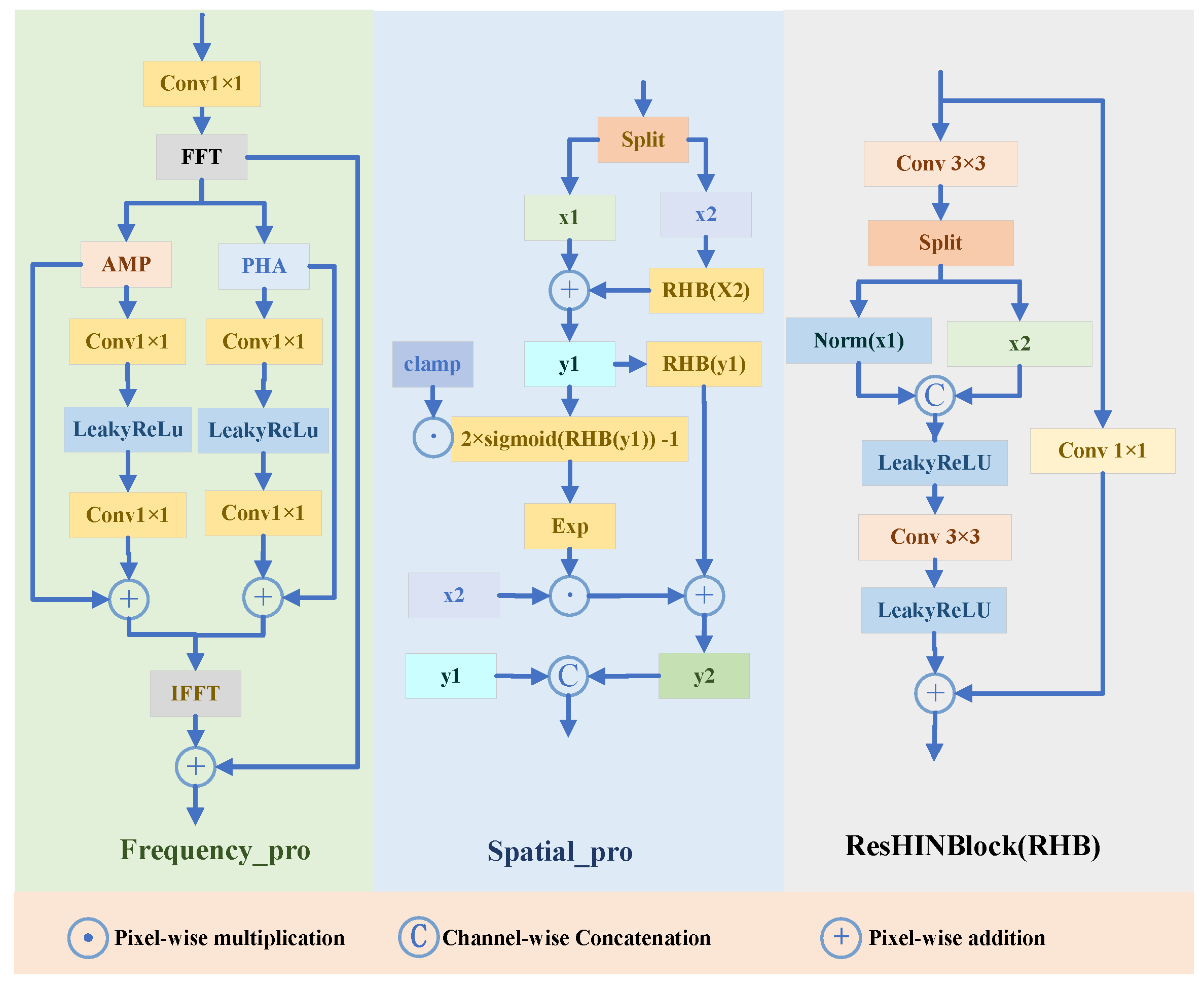

Spectral–Spatial Fusion Block

3.2. Dual-Branch Spectral-Spatial Attention

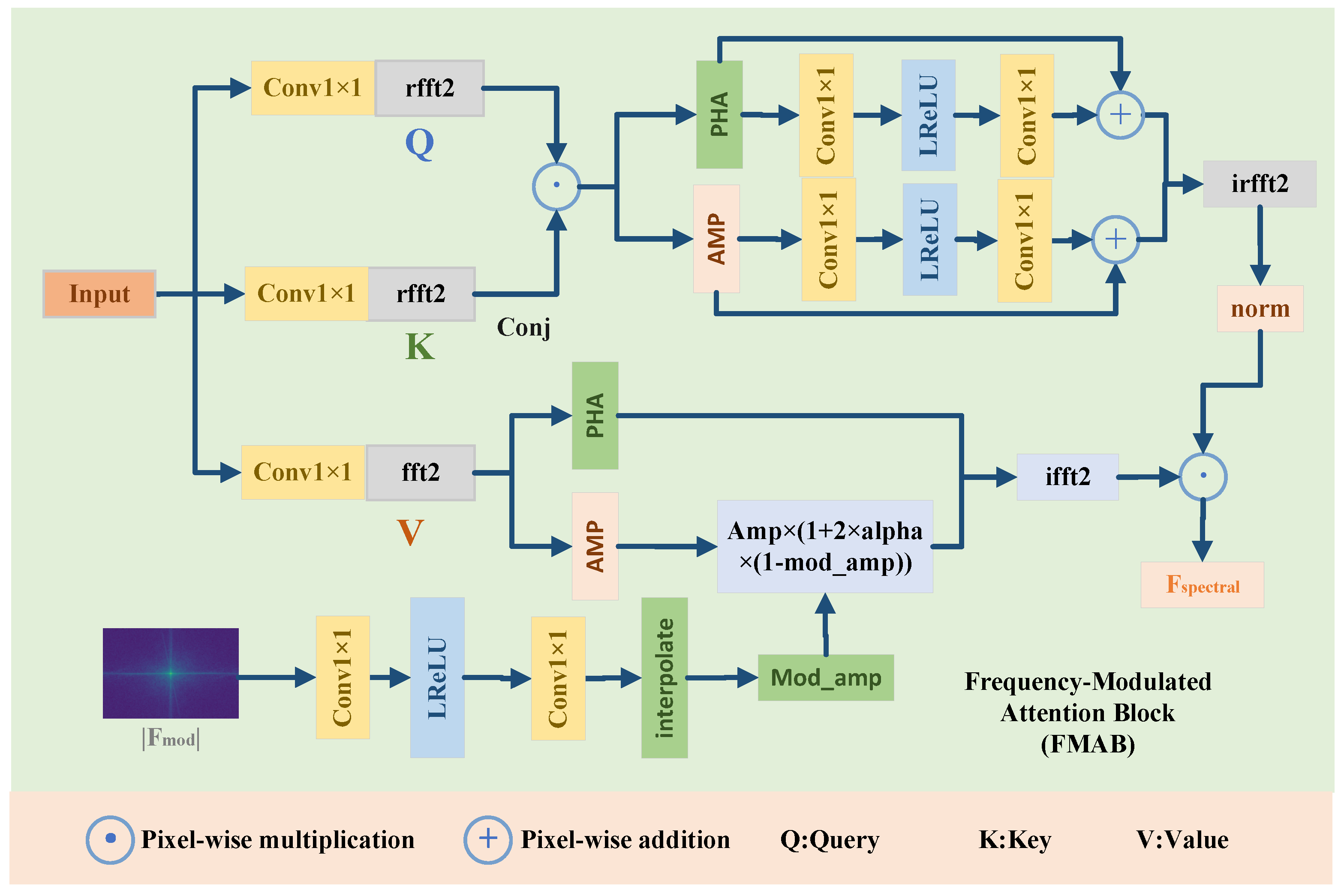

3.2.1. Frequency-Modulated Attention Block

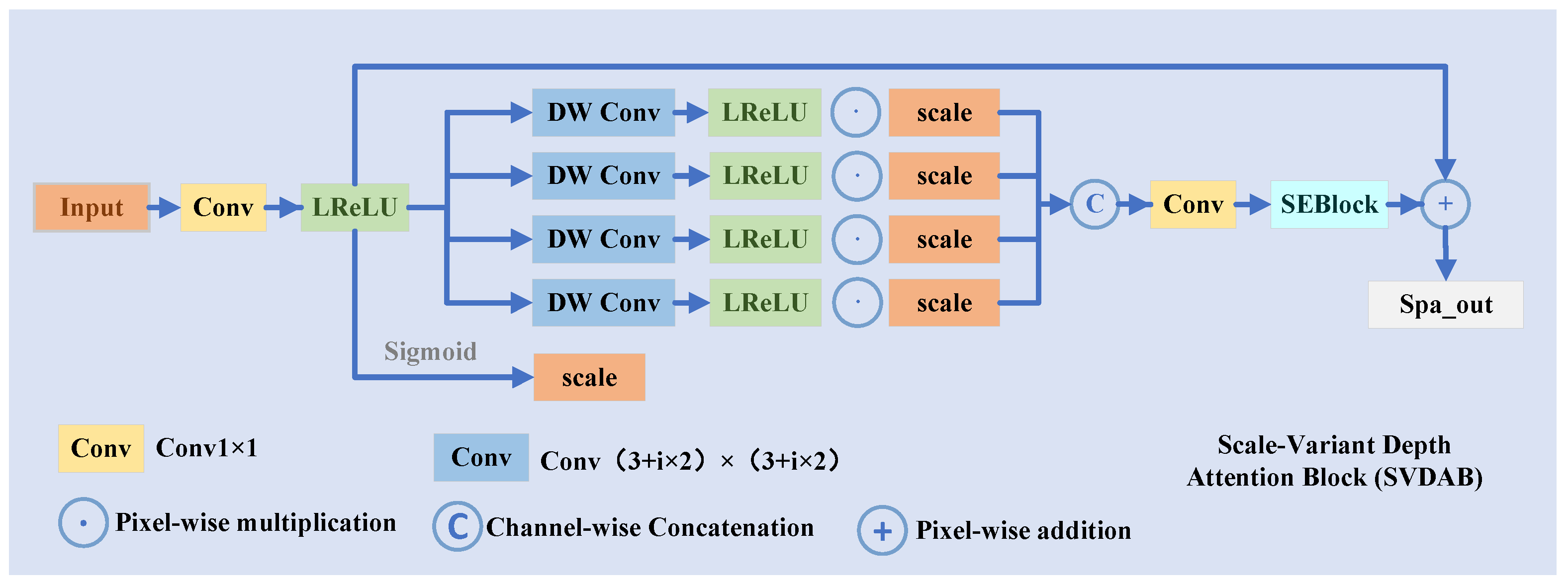

3.2.2. Scale-Variant Depth Attention Block

3.3. Spectral Gated Feed-Forward NetworK

3.4. Loss Function

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Implementation Details

4.2. Datesets and Metric

4.3. Compared Methods

4.4. Visual Comparisons

4.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

| Methods | Venue | LOL-v2-real | LOL-v2-syn | Complexity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR (dB)↑ | SSIM↑ | LPIPS↓ | PSNR (dB)↑ | SSIM↑ | LPIPS↓ | FLOPs (G)↓ | Params (M)↓ | ||

| Kind [4] | ACMM’19 | 17.54 | 0.669 | 0.375 | 16.25 | 0.591 | 0.435 | 34.99 | 8.02 |

| MIRNet [22] | ECCV’20 | 22.11 | 0.794 | 0.145 | 22.52 | 0.900 | 0.057 | 785 | 31.76 |

| RetinexDIP [23] | TCSVT’21 | 14.68 | 0.495 | 0.348 | 15.91 | 0.762 | 0.214 | - | - |

| KinD++ [24] | IJCV’21 | 20.01 | 0.841 | 0.143 | 22.62 | 0.904 | 0.067 | 7484.32 | 8.28 |

| RUAS [6] | CVPR’21 | 18.37 | 0.723 | - | 16.55 | 0.652 | - | 0.83 | 0.003 |

| SNR-Aware [12] | CVPR’22 | 21.48 | 0.849 | 0.169 | 24.14 | 0.928 | 0.056 | 26.35 | 4.01 |

| URetinex [25] | CVPR’22 | 21.16 | 0.840 | 0.144 | 24.14 | 0.928 | - | 5.61 | 0.08 |

| CLIP-LIT [26] | ICCV’23 | 15.18 | 0.529 | 0.369 | 16.19 | 0.775 | 0.204 | 30.58 | 51.84 |

| FourLLIE [19] | ACMM’23 | 22.34 | 0.847 | 0.159 | 24.65 | 0.919 | 0.066 | 13.4 | 0.12 |

| GSAD [27] | NeurIPS’23 | 20.15 | 0.845 | 0.113 | 24.47 | 0.928 | 0.063 | 29.58 | 23.32 |

| NeRCo [28] | ICCV’23 | 19.45 | 0.733 | 0.300 | 20.87 | 0.815 | 0.148 | 21.04 | 8.44 |

| Retinexformer [17] | ICCV’23 | 22.43 | 0.811 | 0.249 | 25.627 | 0.931 | 0.079 | 17.02 | 1.61 |

| AnlightenDiff [18] | TIP’24 | 20.65 | 0.837 | 0.146 | - | - | - | 23.97 | 13.91 |

| Pseudo [29] | TCSVT’24 | 18.46 | 0.81 | 0.153 | 17.88 | 0.76 | 0.142 | 1.48 | 1.54 |

| CSPN [30] | TCSVT’24 | 21.59 | 0.859 | 0.0917 | - | - | - | 60.92 | 1.40 |

| MPC-Net [31] | TCSVT’24 | 22.60 | 0.864 | 0.103 | 25.67 | 0.939 | 0.044 | 4.4 | - |

| DMFourllie [20] | ACMM’24 | 22.64 | 0.858 | 0.052 | 25.83 | 0.931 | 0.023 | 1.69 | 0.41 |

| IGDFormer [32] | PR’25 | 22.73 | 0.833 | - | 25.33 | 0.937 | - | 9.68 | 3.55 |

| DiffDark [33] | PR’25 | 20.84 | 0.868 | 0.1037 | 24.08 | 0.915 | 0.095 | - | - |

| KANfourmer [34] | ACMM’25 | 21.851 | 0.852 | 0.034 | 25.56 | 0.932 | 0.085 | 6.221 | 1.88 |

| AFMNet (Ours) | - | 23.15 | 0.868 | 0.039 | 25.97 | 0.942 | 0.023 | 14.519 | 4.176 |

| Methods | PSNR (dB) ↑ | SSIM ↑ | Methods | PSNR (dB) ↑ | SSIM ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kind | 21.95 | 0.672 | Retinexformer | 29.77 | 0.896 |

| MIRNet | 24.38 | 0.864 | MambaIR | 28.97 | 0.884 |

| RUAS | 23.17 | 0.696 | ECAFormer | 29.11 | 0.874 |

| SDSD | 25.20 | 0.722 | QuadPrior | 22.22 | 0.783 |

| Retinex | 23.17 | 0.696 | Mamballie | 30.12 | 0.900 |

| Restormer | 25.67 | 0.827 | Ours | 31.17 | 0.900 |

| SNR-Aware | 29.44 | 0.894 |

| Methods | LIME | DICM | NPE | MEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kind | 4.772 | 3.614 | 4.175 | 4.819 |

| MIRNet | 6.453 | 4.042 | 5.235 | 5.504 |

| SGM | 5.451 | 4.733 | 5.208 | 5.754 |

| FECNet | 6.041 | 4.139 | 4.500 | 4.707 |

| HDMNet | 6.403 | 4.773 | 5.108 | 5.993 |

| Bread | 4.717 | 4.179 | 4.160 | 5.369 |

| SNR | 4.618 | 3.227 | 3.975 | 4.589 |

| Retinexformer | 3.441 | 4.008 | 3.893 | 3.727 |

| FourLLIE | 4.402 | 3.374 | 3.909 | 4.362 |

| AFMNet | 4.2 | 3.94 | 3.88 | 3.49 |

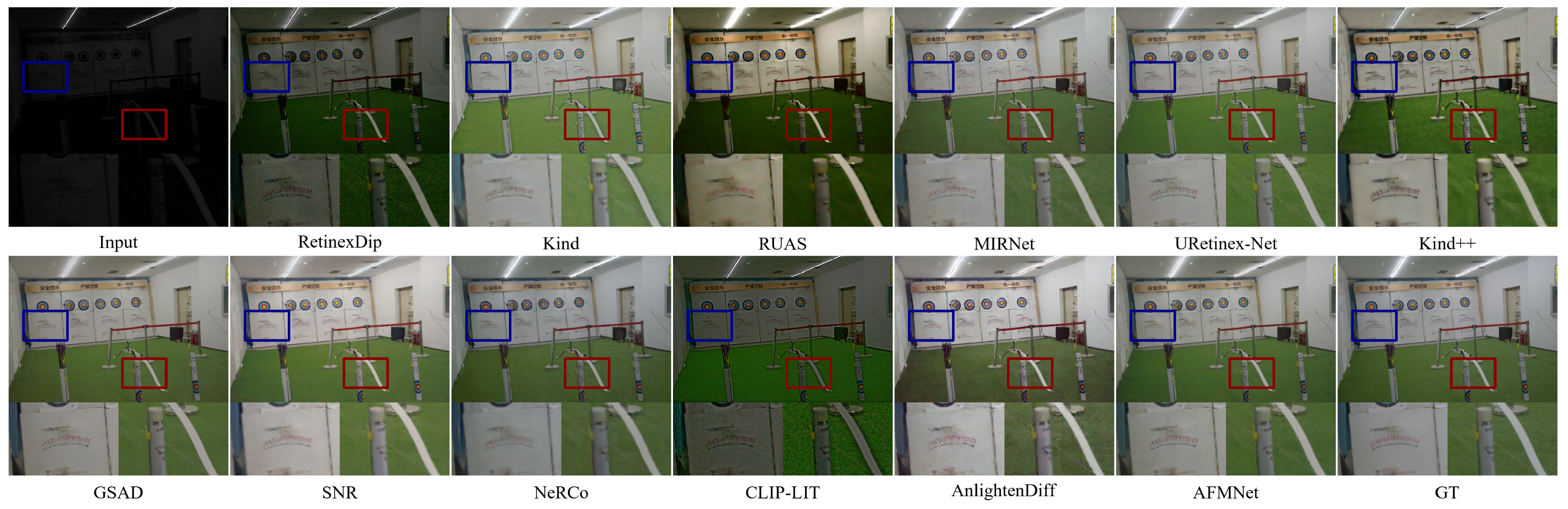

4.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

4.5. Ablation Study

| Metric | AFMNet (Full Model) | w/o Freq. Prior Guidance | w/o Multi-Scale in MSAE | FMAB w/o Prior Guidance | DBSSA w/o Spatial | SSFBlock w/o Freq. Branch | SGFFN to MLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR (dB) ↑ | 23.15 | 22.12 | 22.84 | 22.58 | 22.76 | 22.48 | 22.91 |

| SSIM ↑ | 0.868 | 0.841 | 0.861 | 0.855 | 0.860 | 0.852 | 0.863 |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C.; Lee, C.; Kim, C. Contrast Enhancement Based on Layered Difference Representation of 2D Histograms. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 5372–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobson, D.J.; Rahman, Z.; Woodell, G.A. Properties and performance of a center/surround retinex. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1997, 6, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Wang, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Deep Retinex Decomposition for Low-Light Enhancement. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2018, BMVC 2018, Newcastle, UK, 3–6 September 2018; BMVA Press: Newcastle, UK, 2018. 155p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Kindling the Darkness: A Practical Low-Light Image Enhancer. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM 2019, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Loy, C.C.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Cong, R. Zero-Reference Deep Curve Estimation for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; Computer Vision Foundation: New York, NY, USA; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Luo, Z. Retinex-Inspired Unrolling with Cooperative Prior Architecture Search for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2021, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; Computer Vision Foundation: New York, NY, USA; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 10561–10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qi, H.; Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z. A Lightweight Image Entropy-Based Divide-and-Conquer Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, ICME 2022, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, R.; Shahnawazuddin, S. Advancing low-light image enhancement: An entropy-driven approach with reduced defects. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Sparse Gradient Regularized Deep Retinex Network for Robust Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2072–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Xu, X.; Fu, C.; Lu, J.; Yu, B.; Jia, J. Seeing Dynamic Scene in the Dark: A High-Quality Video Dataset with Mechatronic Alignment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2021, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 9680–9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Quero, C.; Rondon, I.; Martinez-Carranza, J. Improving NIR single-pixel imaging: Using deep image prior and GANs. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2025, 42, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C.; Jia, J. SNR-Aware Low-light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 17693–17703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Hou, Y.; Ren, D.; Liu, L.; Zhu, F.; Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Shao, L. STAR: A Structure and Texture Aware Retinex Model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 5022–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A General U-Shaped Transformer for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 17662–17672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Wu, Z.; Dai, Q.; Hu, H.; Qiao, Y.; Jiang, Y. ResFormer: Scaling ViTs with Multi-Resolution Training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 22721–22731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Bian, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Timofte, R.; Zhang, Y. Retinexformer: One-Stage Retinex-Based Transformer for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2023, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 12470–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Siu, W.; Chan, Y.; Chan, H.A. AnlightenDiff: Anchoring Diffusion Probabilistic Model on Low Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 6324–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Jin, Z. FourLLIE: Boosting Low-Light Image Enhancement by Fourier Frequency Information. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM 2023, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 7459–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, P.; Zhao, M.; Lv, H. DMFourLLIE: Dual-Stage and Multi-Branch Fourier Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM 2024, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 7434–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, C.O.; Leykam, D.; Ojeda, I.R. Res-U2Net: Untrained Deep Learning for Phase Retrieval and Image Reconstruction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.06657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.H.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.; Shao, L. Learning Enriched Features for Real Image Restoration and Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020—16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. Proceedings, Part XXV. Volume 12370, pp. 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xiong, B.; Wang, L.; Ou, Q.; Yu, L.; Kuang, F. RetinexDIP: A Unified Deep Framework for Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 1076–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J. Beyond Brightening Low-light Images. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 1013–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Weng, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Jiang, J. URetinex-Net: Retinex-Based Deep Unfolding Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 5891–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Feng, R.; Loy, C.C. Iterative Prompt Learning for Unsupervised Backlit Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2023, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 8060–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhu, Z.; Hou, J.; Liu, H.; Zeng, H.; Yuan, H. Global Structure-Aware Diffusion Process for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Ding, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Implicit Neural Representation for Cooperative Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2023, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 12872–12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; You, B.; Yue, G.; Ling, J. Pseudo-Supervised Low-Light Image Enhancement with Mutual Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Tu, L.; Patsch, C.; Jin, Z. CSPN: A Category-Specific Processing Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 11929–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, C.; Han, F.; Wang, L.; Duan, S.; Huang, T. MPC-Net: Multi-Prior Collaborative Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 10385–10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, Z.; Xu, W.A. An illumination-guided dual attention vision transformer for low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Luo, T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; He, Z. DiffDark: Multi-prior integration driven diffusion model for low-light image enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 168, 111814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wei, Z.; Wu, H.; Sun, L.; Zhan, T. KANformer: Dual-Priors-Guided Low-Light Enhancement via KAN and Transformer. ACM Trans. Multim. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2025, 21, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Setting A | Setting B | Setting C | AFMNet (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ✓ | ||||

| PSNR (dB) ↑ | 22.34 | 22.75 | 22.98 | 23.15 |

| SSIM ↑ | 0.849 | 0.858 | 0.864 | 0.868 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, Q.; Ma, L. AFMNet: A Dual-Domain Collaborative Network with Frequency Prior Guidance for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Entropy 2025, 27, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121220

An Q, Ma L. AFMNet: A Dual-Domain Collaborative Network with Frequency Prior Guidance for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121220

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Qianqian, and Long Ma. 2025. "AFMNet: A Dual-Domain Collaborative Network with Frequency Prior Guidance for Low-Light Image Enhancement" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121220

APA StyleAn, Q., & Ma, L. (2025). AFMNet: A Dual-Domain Collaborative Network with Frequency Prior Guidance for Low-Light Image Enhancement. Entropy, 27(12), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121220