Non-Parametric Goodness-of-Fit Tests Using Tsallis Entropy Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principle of Maximum Entropy

3. Tsallis Entropy

3.1. Generalized Gaussian Distributions Under Tsallis Entropy

3.2. The q-Exponential and q-Gaussian Distributions

3.3. Multivariate q-Gaussian and Its Entropy

4. Tsallis Entropy: Statistical Estimation Method

Assumptions and Results

5. Test Statistics and Hypothesis Testing for

5.1. Test Statistics

- For , with , definewhere denotes the maximum Tsallis entropy under the assumed model.

- For , with , definewhere .

Null Calibration Policy

| Algorithm 1 Bootstrap calibration for |

|

5.2. Asymptotic Behavior

6. Numerical Experiments

6.1. Challenges in Null Distribution

6.2. Multivariate q-Gaussian Sampling: Exact Radial Laws with Correctness

6.2.1. Radial Laws

- Case (compact support). The joint density factorizes in polar coordinates as follows:Let . Then,

- Case (heavy tails). The power-law exponent can be matched with that of a multivariate Student distribution to obtainThe q-Gaussian is equivalent to the multivariate Student- distribution up to a scaling of . Therefore,in other words, follows a scaled F (or, equivalently, Beta-prime) distribution. Equivalently,with and independent.

6.2.2. Correctness

6.2.3. Exact Samplers

| Algorithm 2 Exact sampler for the multivariate q-Gaussian distribution. |

|

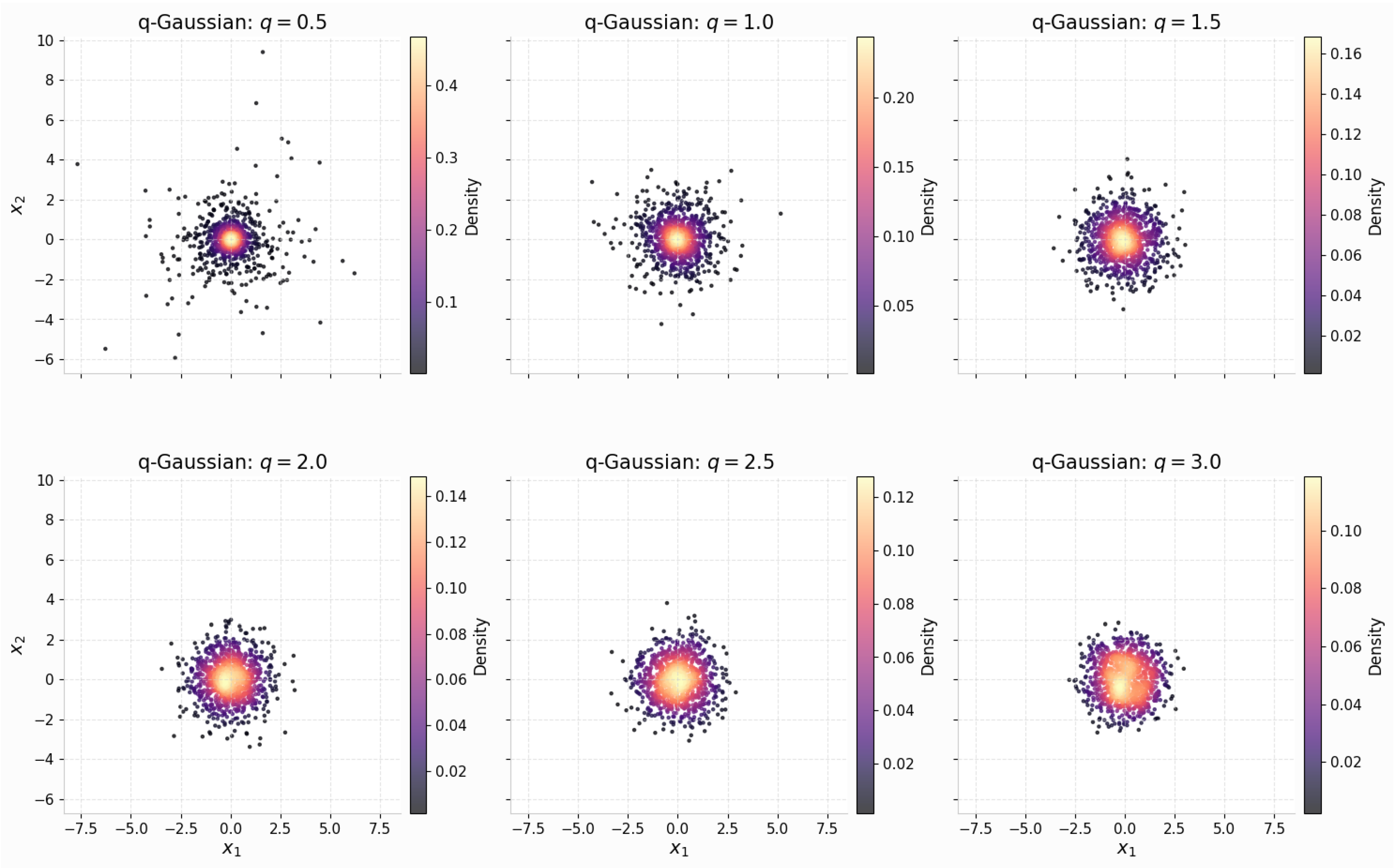

6.3. Stochastic Generation of q-Gaussian Samples

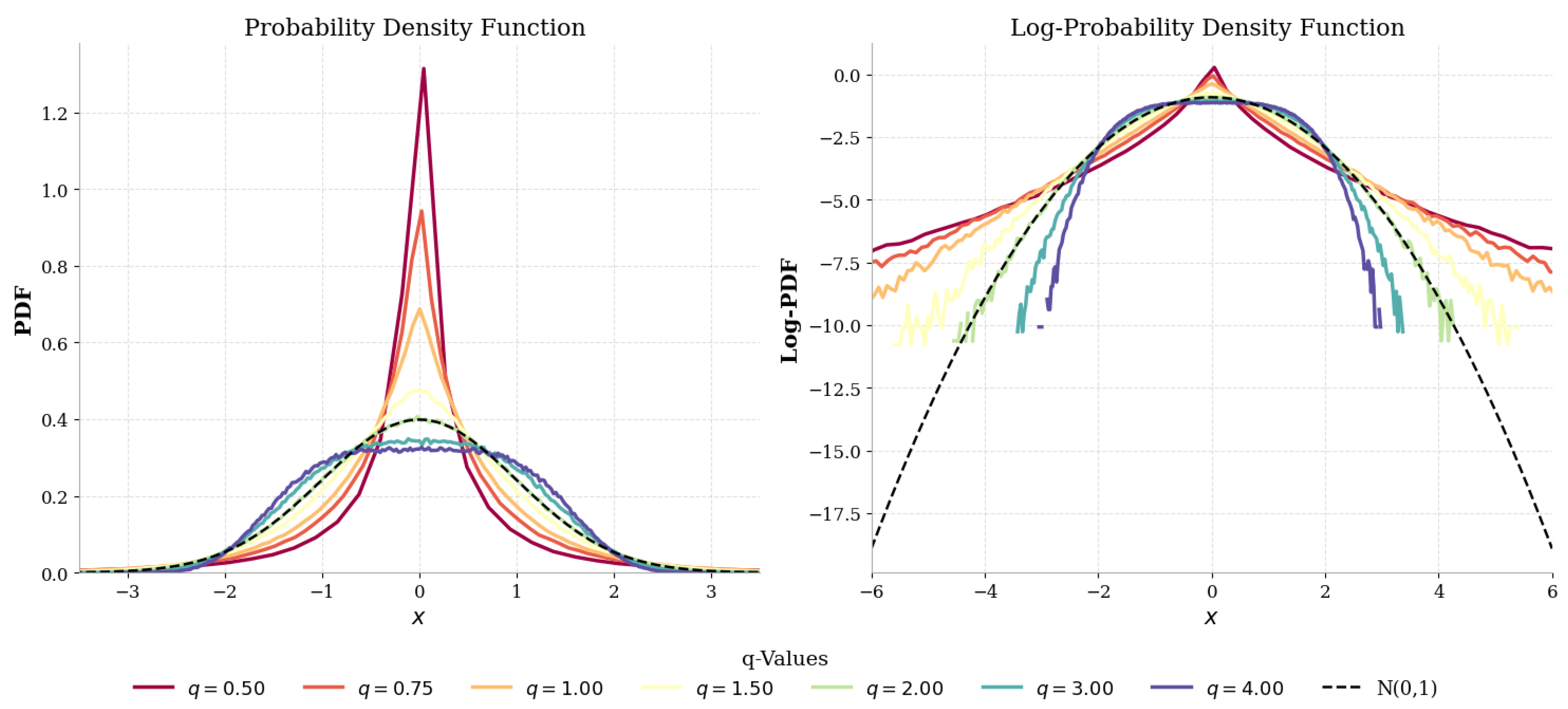

6.4. Empirical Density and Analysis of Log Density

6.5. Bootstrap vs. Asymptotic Normal Calibration

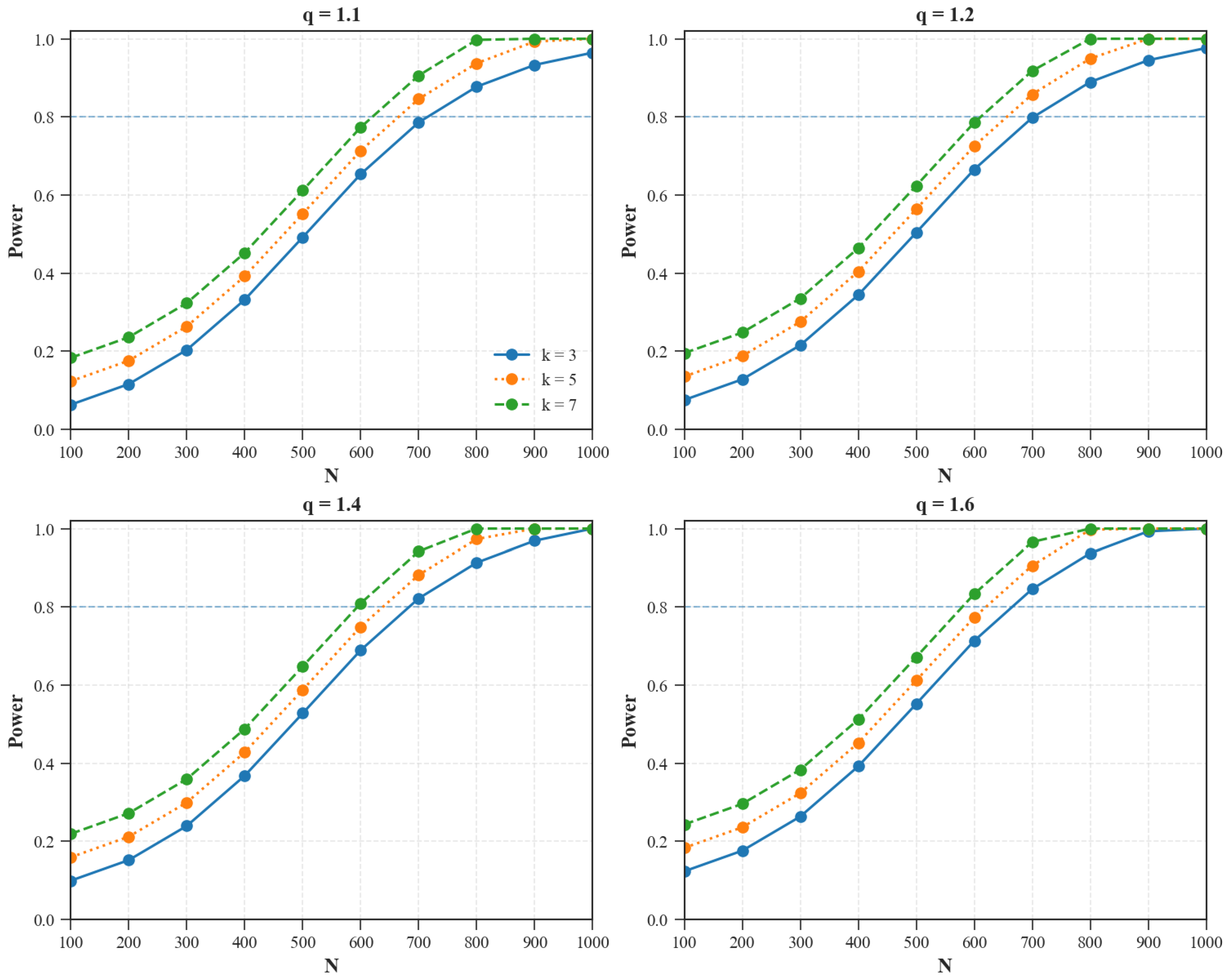

6.6. Benchmarking and Power Analysis

- (i)

- (ii)

- Divergence-based robust tests use Kullback–Leibler and Hellinger distances [32].

- mean-shifted alternatives ;

- scale-inflated alternatives ;

- contamination mixtures .

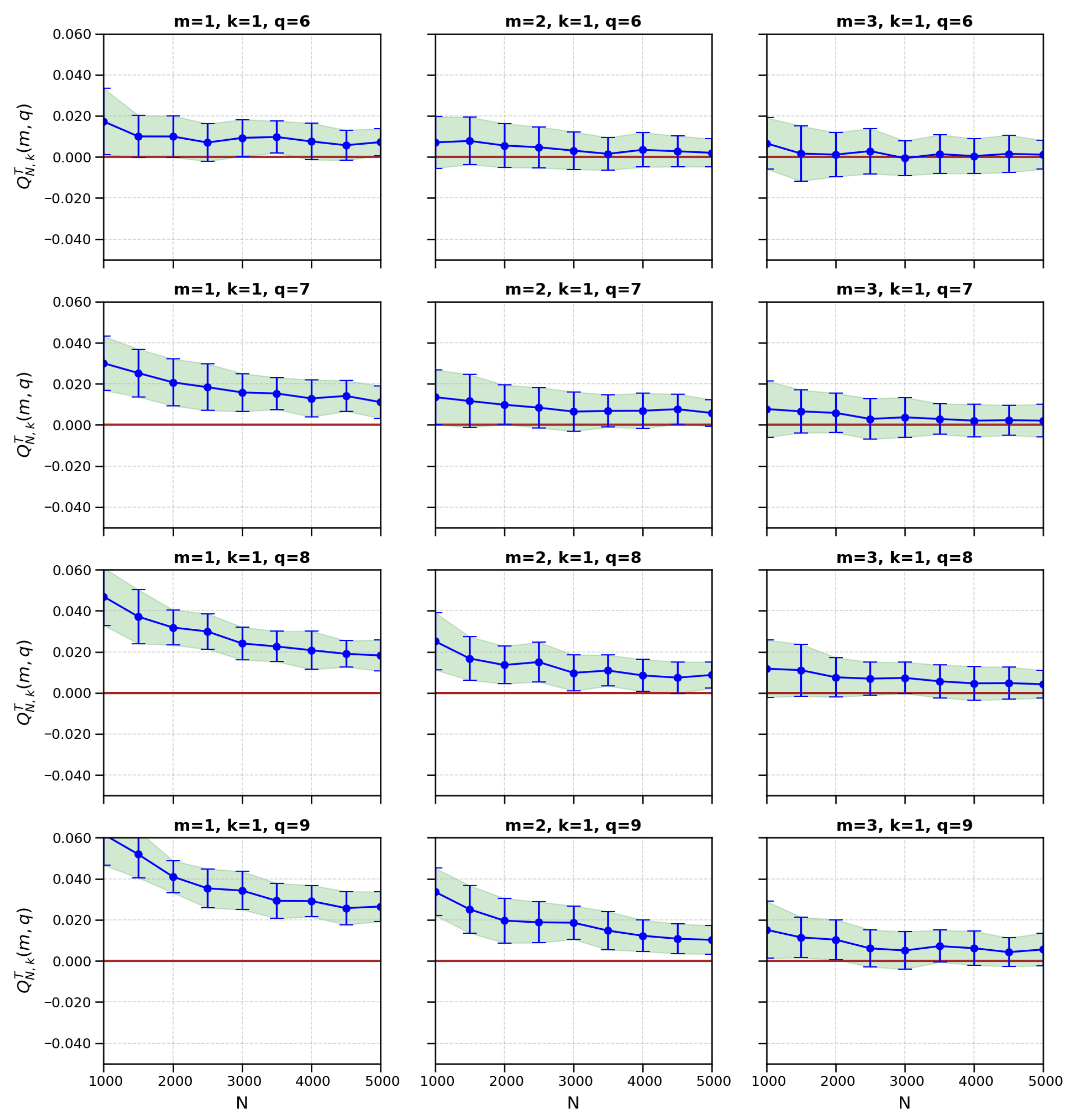

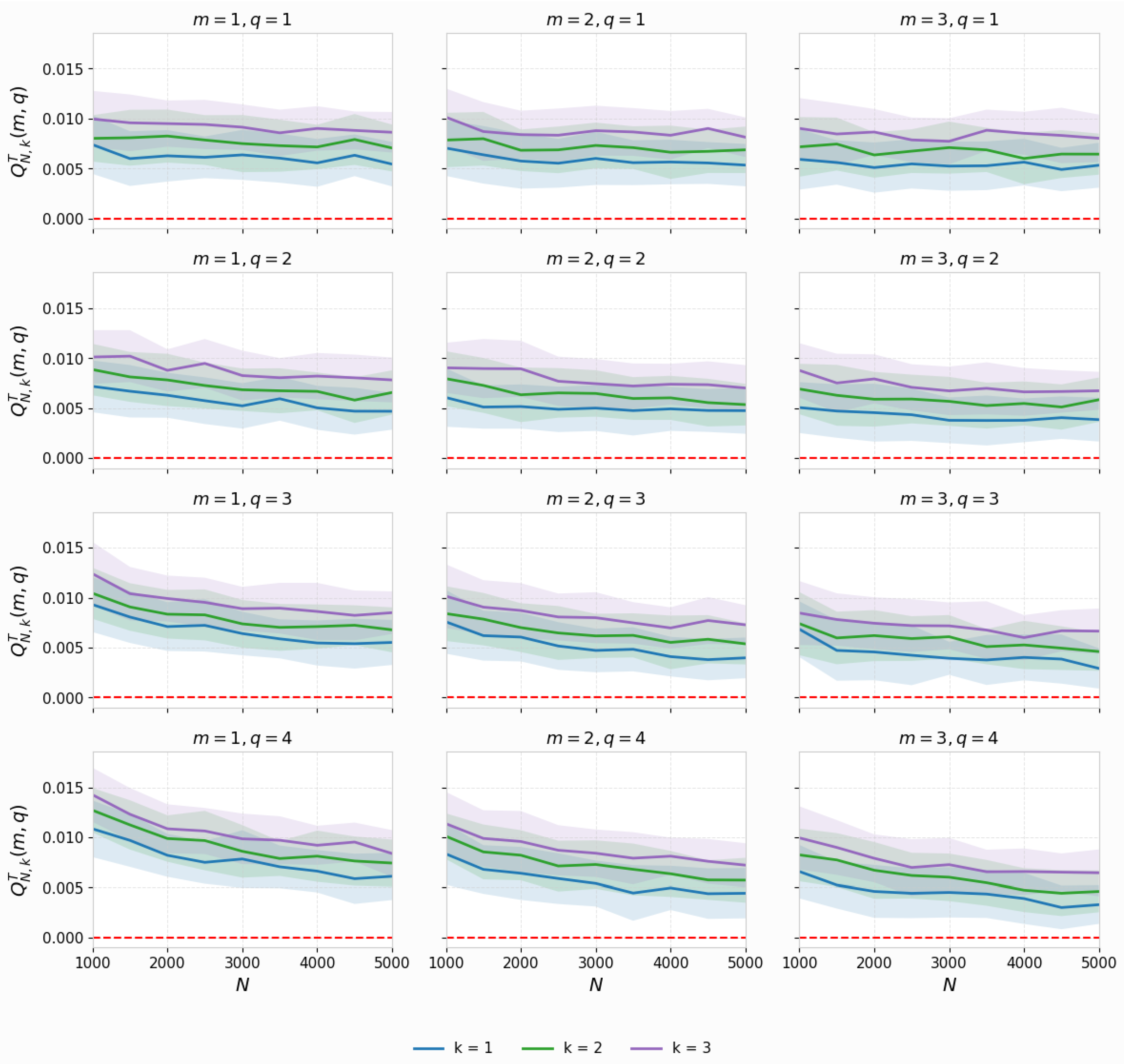

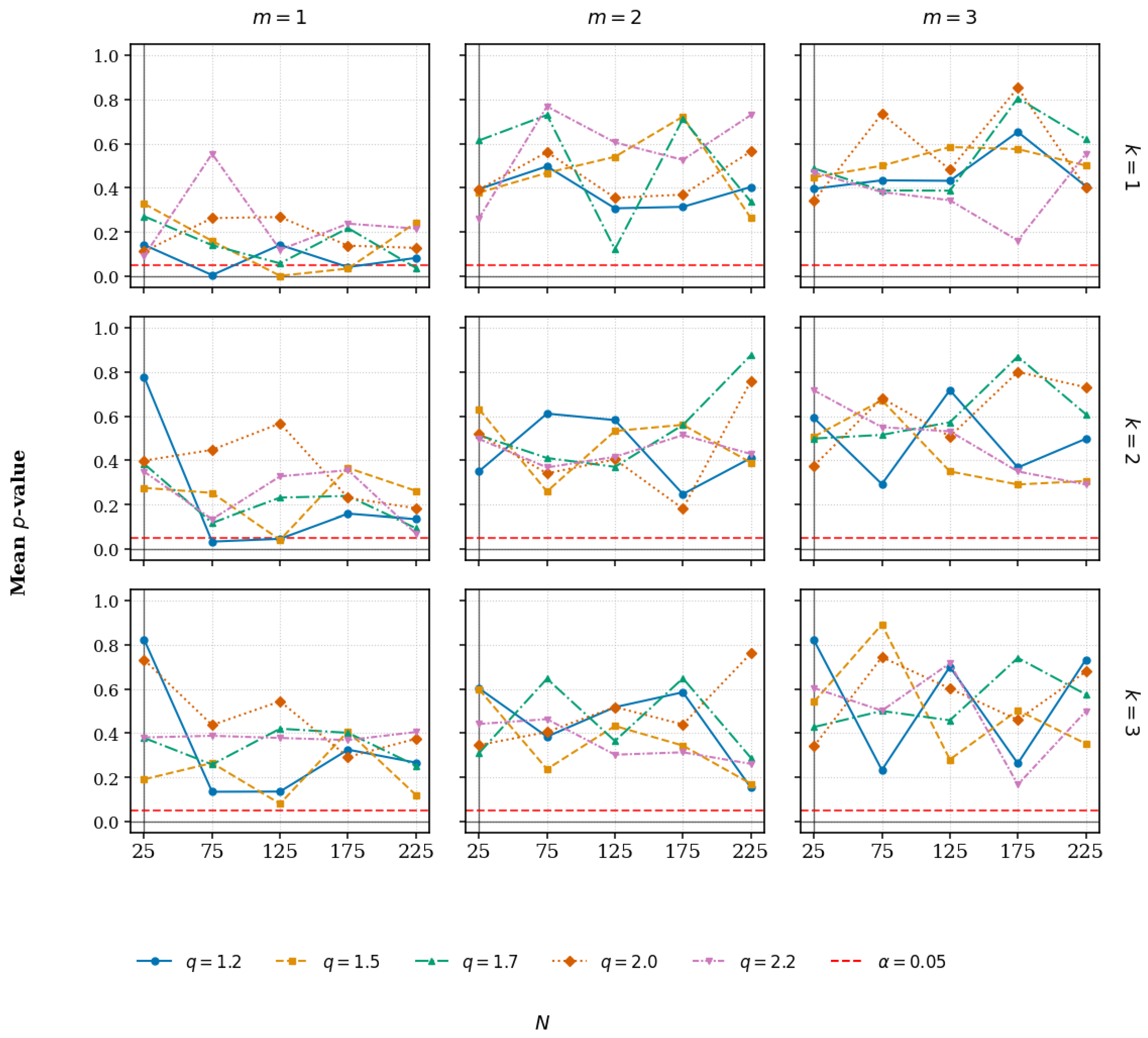

6.7. Monte Carlo Study of Test Statistic Behavior

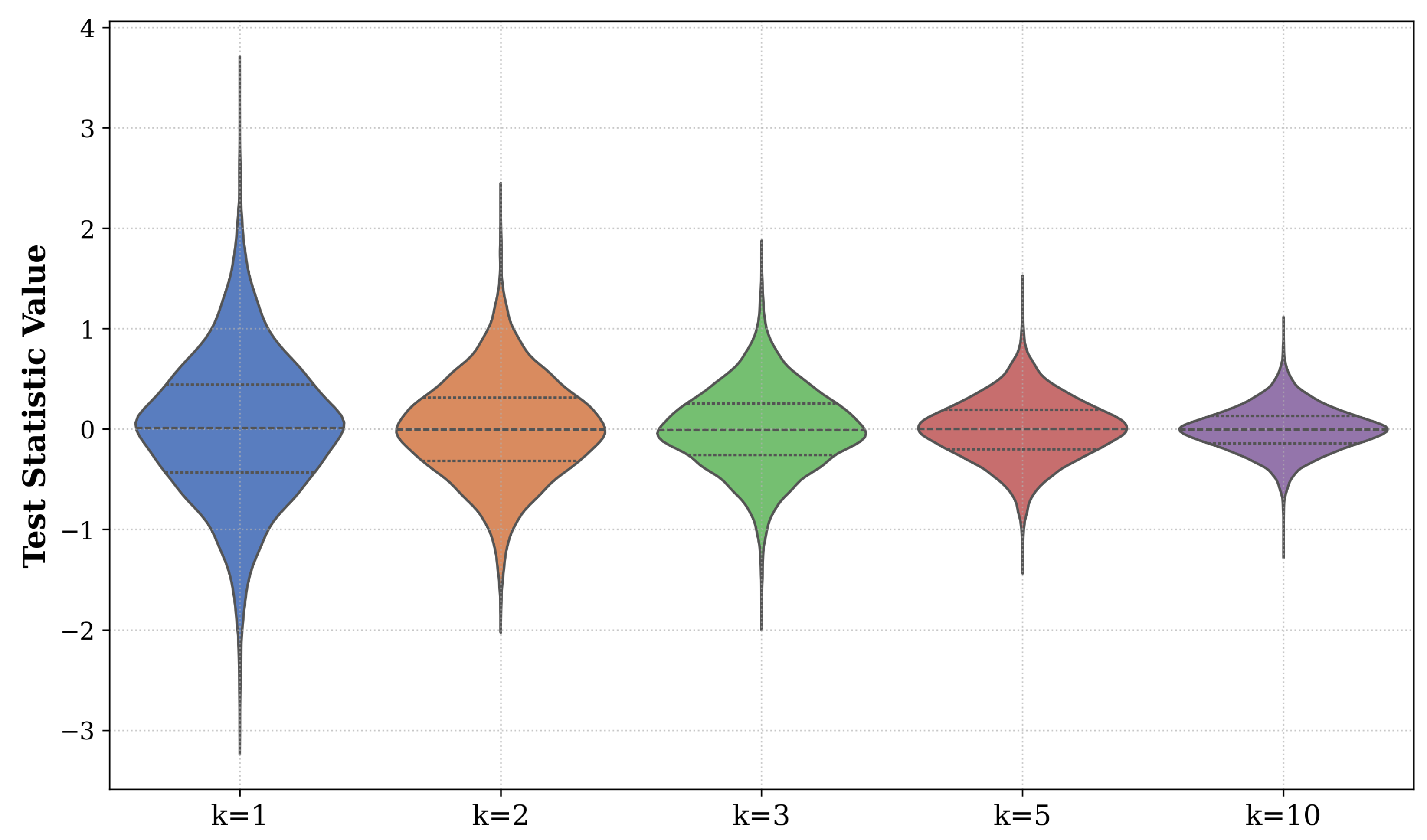

6.8. Violin Plots and Distributional Analysis

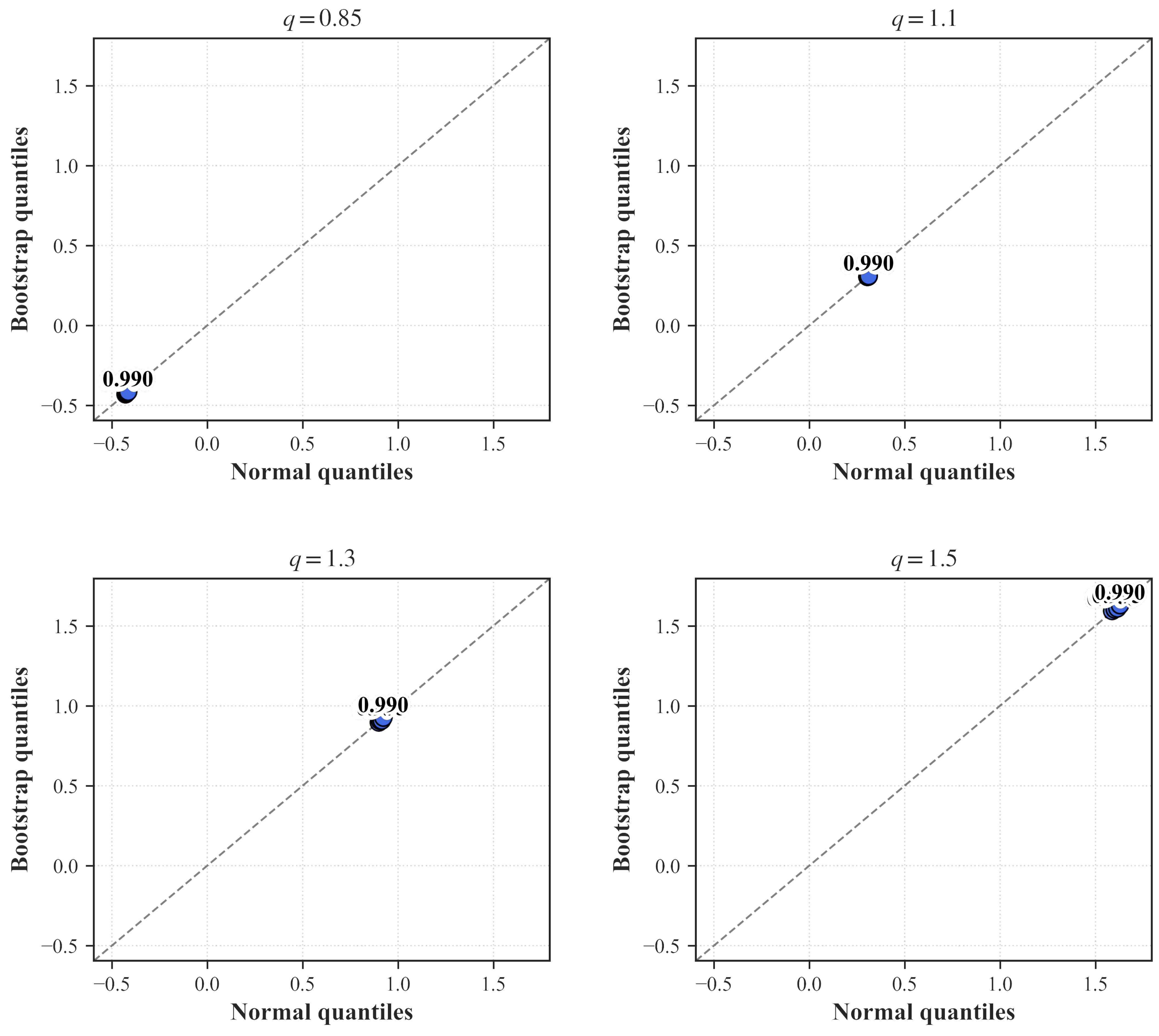

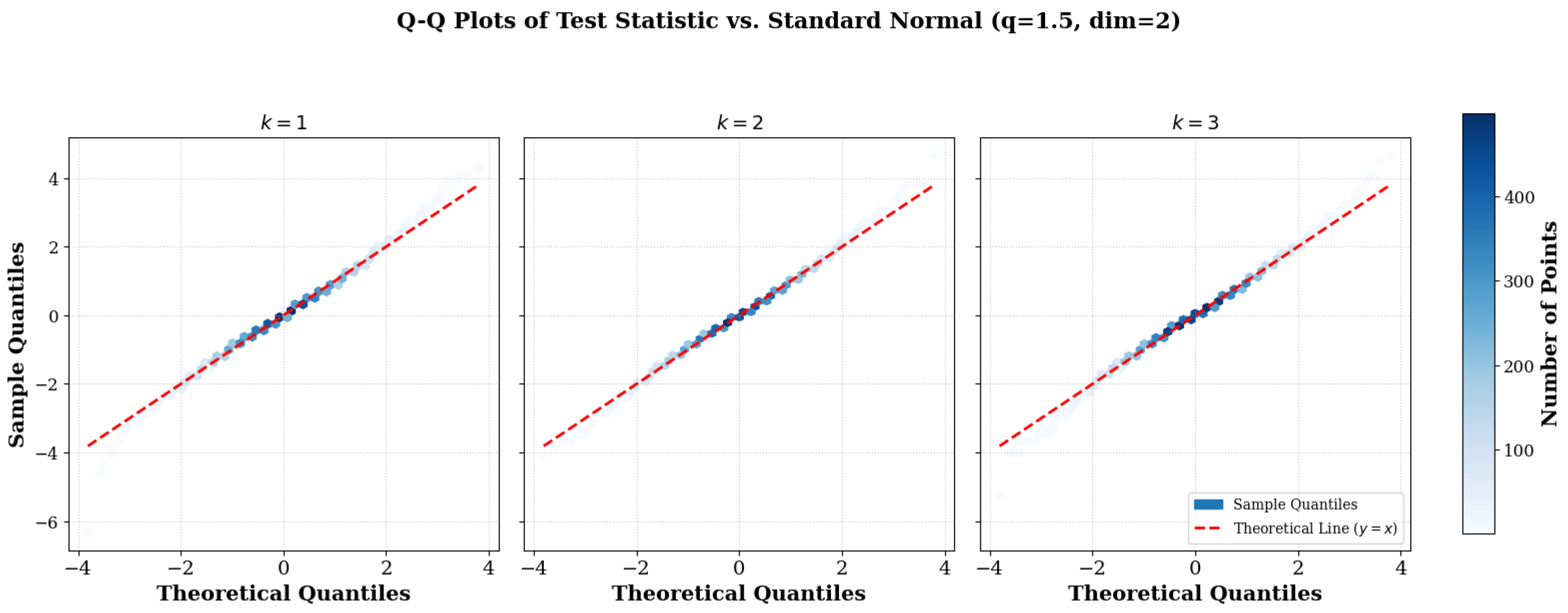

6.9. Plot of Q–Q for Normality Check

6.10. Empirical Distribution of the Test Statistics

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| q | N | m = 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | ||

| 1.2 | 100 | [0.03767, 0.03866] | [0.03767, 0.03866] | [0.03767, 0.03866] |

| 200 | [0.03773, 0.03875] | [0.03773, 0.03875] | [0.03773, 0.03875] | |

| 300 | [0.03779, 0.03874] | [0.03779, 0.03874] | [0.03779, 0.03874] | |

| 400 | [0.03754, 0.03852] | [0.03754, 0.03852] | [0.03754, 0.03852] | |

| 500 | [0.03771, 0.03882] | [0.03771, 0.03882] | [0.03771, 0.03882] | |

| 600 | [0.03770, 0.03879] | [0.03770, 0.03879] | [0.03770, 0.03879] | |

| 700 | [0.03777, 0.03875] | [0.03777, 0.03875] | [0.03777, 0.03875] | |

| 800 | [0.03776, 0.03886] | [0.03776, 0.03886] | [0.03776, 0.03886] | |

| 900 | [0.03781, 0.03876] | [0.03781, 0.03876] | [0.03781, 0.03876] | |

| 1000 | [0.03775, 0.03877] | [0.03775, 0.03877] | [0.03775, 0.03877] | |

| 1.5 | 100 | [0.03667, 0.03766] | [0.03667, 0.03766] | [0.03667, 0.03766] |

| 200 | [0.03673, 0.03775] | [0.03673, 0.03775] | [0.03673, 0.03775] | |

| 300 | [0.03679, 0.03774] | [0.03679, 0.03774] | [0.03679, 0.03774] | |

| 400 | [0.03654, 0.03752] | [0.03654, 0.03752] | [0.03654, 0.03752] | |

| 500 | [0.03671, 0.03782] | [0.03671, 0.03782] | [0.03671, 0.03782] | |

| 600 | [0.03670, 0.03779] | [0.03670, 0.03779] | [0.03670, 0.03779] | |

| 700 | [0.03677, 0.03775] | [0.03677, 0.03775] | [0.03677, 0.03775] | |

| 800 | [0.03676, 0.03786] | [0.03676, 0.03786] | [0.03676, 0.03786] | |

| 900 | [0.03681, 0.03776] | [0.03681, 0.03776] | [0.03681, 0.03776] | |

| 1000 | [0.03675, 0.03777] | [0.03675, 0.03777] | [0.03675, 0.03777] | |

| 2.5 | 100 | [0.03467, 0.03566] | [0.03467, 0.03566] | [0.03467, 0.03566] |

| 200 | [0.03473, 0.03575] | [0.03473, 0.03575] | [0.03473, 0.03575] | |

| 300 | [0.03479, 0.03574] | [0.03479, 0.03574] | [0.03479, 0.03574] | |

| 400 | [0.03454, 0.03552] | [0.03454, 0.03552] | [0.03454, 0.03552] | |

| 500 | [0.03471, 0.03582] | [0.03471, 0.03582] | [0.03471, 0.03582] | |

| 600 | [0.03470, 0.03579] | [0.03470, 0.03579] | [0.03470, 0.03579] | |

| 700 | [0.03477, 0.03575] | [0.03477, 0.03575] | [0.03477, 0.03575] | |

| 800 | [0.03476, 0.03586] | [0.03476, 0.03586] | [0.03476, 0.03586] | |

| 900 | [0.03481, 0.03576] | [0.03481, 0.03576] | [0.03481, 0.03576] | |

| 1000 | [0.03475, 0.03577] | [0.03475, 0.03577] | [0.03475, 0.03577] | |

| q | N | m = 2 | m = 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | ||

| 1.2 | 100 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 |

| 200 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| 300 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 400 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 500 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 600 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 700 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 800 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 900 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 1000 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| 1.5 | 100 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 |

| 200 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| 300 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 400 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 500 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 600 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 700 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 800 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 900 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 1000 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| 2.5 | 100 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 |

| 200 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| 300 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 400 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 500 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 600 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 700 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | 0.00025 | |

| 800 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | 0.00028 | |

| 900 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | 0.00024 | |

| 1000 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | 0.00026 | |

| Test | Mean Size | Power | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift () | Scale () | Contam. () | ||

| Tsallis () | 0.051 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.76 |

| Shannon () | 0.048 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.58 |

| Rényi () | 0.050 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.61 |

| LRT (GGD) | 0.049 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.40 |

| KL-divergence | 0.052 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.55 |

References

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F.; Nock, R. On Rényi and Tsallis Entropies and Divergences for Exponential Families. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1105.3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C. Possible Generalization of Boltzmann–Gibbs Statistics. J. Stat. Phys. 1988, 52, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.J.V. Generalization of Shannon’s Theorem for Tsallis Entropy. J. Math. Phys. 1997, 38, 4104–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomani, G.; Kayid, M. Further Properties of Tsallis Entropy and Its Application. Entropy 2023, 25, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, M.M.; Gupta, N. Some Characterization Results on Dynamic Cumulative Residual Tsallis Entropy. J. Probab. Stat. 2015, 2015, 694203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Some Results on Tsallis Entropy Measure and k-Record Values. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 462, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Characterization Results Based on Dynamic Tsallis Cumulative Residual Entropy. Commun. Stat. Methods 2017, 46, 8343–8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulinski, A.; Dimitrov, D. Statistical Estimation of the Shannon Entropy. Acta Math. Sin. Engl. Ser. 2019, 35, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulinski, A.; Kozhevin, A. Statistical Estimation of Conditional Shannon Entropy. ESAIM Probab. Stat. 2019, 23, 350–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrett, T.B.; Samworth, R.J.; Yuan, M. Efficient Multivariate Entropy Estimation via k-Nearest Neighbour Distances. Ann. Stat. 2019, 47, 288–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrett, T.B.; Samworth, R.J. Nonparametric Independence Testing via Mutual Information. Biometrika 2019, 106, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuichi, S. On the Maximum Entropy Principle and the Minimization of the Fisher Information in Tsallis Statistics. J. Math. Phys. 2009, 50, 013303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuichi, S. Information Theoretical Properties of Tsallis Entropies and Tsallis Relative Entropies. J. Math. Phys. 2006, 47, 023302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaro, N. Random Variate Generation from Multivariate Exponential Power Distribution. Stat. Appl. 2004, 2, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- De Simoni, S. Su una Estensione dello Schema delle Curve Normali di Ordine r alle Variabili Doppie. Statistica 1968, 37, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, Y. Consistency Property of Elliptic Probability Density Functions. J. Multivar. Anal. 1994, 51, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.; Gomez-Villegas, M.A.; Marín, J.M. A Multivariate Generalization of the Power Exponential Family of Distributions. Commun. Stat. Methods 1998, 27, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.T.; Kotz, S. Symmetric Multivariate and Related Distributions; Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1990; Volume 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadirci, M.S.; Evans, D.; Leonenko, N.N.; Makogin, V. Entropy-Based Test for Generalised Gaussian Distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2022, 173, 107502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Nicolás, F.; Pennini, F.; Plastino, A. Tsallis’ Entropy Maximization Procedure Revisited. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2000, 286, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S. Heat and Entropy in Nonextensive Thermodynamics: Transmutation from Tsallis Theory to Rényi-Entropy-Based Theory. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2001, 300, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyari, H. The Unique Non Self-Referential q-Canonical Distribution and the Physical Temperature Derived from the Maximum Entropy Principle in Tsallis Statistics. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 2006, 162, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonenko, N.N.; Pronzato, L.; Savani, V. A Class of Rényi Information Estimators for Multidimensional Densities. Ann. Stat. 2008, 36, 2153–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsgaarden, D.O.; Quesenberry, C.P. A Nonparametric Estimate of a Multivariate Density Function. Ann. Math. Stat. 1965, 36, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devroye, L.P.; Wagner, T.J. The Strong Uniform Consistency of Nearest Neighbor Density Estimates. Ann. Stat. 1977, 5, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadirci, M.S.; Evans, D.; Leonenko, N.N.; Seleznjev, O. Statistical Tests Based on Rényi Entropy Estimation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadirci, M.S. Entropy-Based Goodness-of-Fit Tests for Multivariate Distributions. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Delattre, S.; Fournier, N. On the Kozachenko–Leonenko Entropy Estimator. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2017, 185, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, M.D.; Yukich, J.E. Laws of Large Numbers and Nearest Neighbor Distances. In Advances in Directional and Linear Statistics; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, S.; Nadarajah, S. Multivariate t-Distributions and Their Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, L. Statistical Inference Based on Divergence Measures; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Purpose | N/viz | M (rep.) | k | m | q | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC sims | 1000 | Var. | Convergence/consistency | |||

| Density plots | – | – | 1 | Viz. only | ||

| Violin/QQ | 1000 | 1000 | 2 | Normality check | ||

| Crit. | 1000 | thresholds |

| q | N | m = 2 | m = 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | ||

| 1.2 | 100 | 0.03127 | 0.03000 | 0.02659 | 0.03072 | 0.02898 | 0.02969 |

| 200 | 0.03181 | 0.03051 | 0.02905 | 0.03056 | 0.03182 | 0.02725 | |

| 300 | 0.02874 | 0.03187 | 0.03063 | 0.02902 | 0.02562 | 0.03294 | |

| 400 | 0.03118 | 0.02641 | 0.03128 | 0.02883 | 0.02660 | 0.03045 | |

| 500 | 0.03300 | 0.02898 | 0.02929 | 0.02796 | 0.03089 | 0.03099 | |

| 600 | 0.03064 | 0.02871 | 0.03097 | 0.02968 | 0.02909 | 0.02714 | |

| 700 | 0.02996 | 0.03009 | 0.02476 | 0.03131 | 0.03267 | 0.02884 | |

| 800 | 0.03019 | 0.02684 | 0.03048 | 0.02993 | 0.02962 | 0.02895 | |

| 900 | 0.03177 | 0.02882 | 0.03261 | 0.03034 | 0.03099 | 0.02893 | |

| 1000 | 0.03079 | 0.03206 | 0.02881 | 0.03010 | 0.02946 | 0.02978 | |

| 1.5 | 100 | 0.02912 | 0.03386 | 0.02988 | 0.02988 | 0.02828 | 0.02485 |

| 200 | 0.02905 | 0.02997 | 0.03007 | 0.02933 | 0.02865 | 0.03134 | |

| 300 | 0.02852 | 0.02648 | 0.03056 | 0.03181 | 0.02937 | 0.02675 | |

| 400 | 0.02734 | 0.03029 | 0.02917 | 0.03009 | 0.02674 | 0.02943 | |

| 500 | 0.03059 | 0.02816 | 0.03036 | 0.03042 | 0.03302 | 0.03244 | |

| 600 | 0.03115 | 0.02998 | 0.03105 | 0.03163 | 0.03039 | 0.02986 | |

| 700 | 0.03164 | 0.03099 | 0.02826 | 0.03181 | 0.02947 | 0.02999 | |

| 800 | 0.03029 | 0.02781 | 0.03065 | 0.02941 | 0.02927 | 0.02920 | |

| 900 | 0.02849 | 0.03079 | 0.02913 | 0.02989 | 0.03007 | 0.02513 | |

| 1000 | 0.03143 | 0.02950 | 0.03023 | 0.03059 | 0.03115 | 0.02866 | |

| 2.5 | 100 | 0.02811 | 0.02875 | 0.02882 | 0.02872 | 0.03005 | 0.03042 |

| 200 | 0.02976 | 0.02930 | 0.02910 | 0.03115 | 0.02961 | 0.03185 | |

| 300 | 0.03042 | 0.02860 | 0.02629 | 0.03276 | 0.02899 | 0.03013 | |

| 400 | 0.03084 | 0.02722 | 0.02662 | 0.03138 | 0.03100 | 0.03037 | |

| 500 | 0.03060 | 0.02875 | 0.02885 | 0.02939 | 0.03217 | 0.02747 | |

| 600 | 0.02972 | 0.02692 | 0.03030 | 0.03267 | 0.03116 | 0.02934 | |

| 700 | 0.02947 | 0.03107 | 0.02988 | 0.02935 | 0.03057 | 0.03037 | |

| 800 | 0.02583 | 0.03158 | 0.02981 | 0.03081 | 0.03048 | 0.02846 | |

| 900 | 0.02913 | 0.03029 | 0.02897 | 0.03186 | 0.02851 | 0.03245 | |

| 1000 | 0.02899 | 0.03079 | 0.03024 | 0.02940 | 0.02842 | 0.03047 | |

| q | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | |

| 1.2 | 0.0085 | 0.0111 | 0.0093 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 |

| 1.5 | 0.0047 | 0.0050 | 0.0045 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 1.7 | 0.0015 | 0.0011 | 0.0014 | −0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| 2.0 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 2.2 | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 |

| 2.5 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | −0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

| 3.0 | −0.0004 | −0.0004 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 |

| 3.5 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| 4.0 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cadirci, M.S. Non-Parametric Goodness-of-Fit Tests Using Tsallis Entropy Measures. Entropy 2025, 27, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121210

Cadirci MS. Non-Parametric Goodness-of-Fit Tests Using Tsallis Entropy Measures. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121210

Chicago/Turabian StyleCadirci, Mehmet Siddik. 2025. "Non-Parametric Goodness-of-Fit Tests Using Tsallis Entropy Measures" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121210

APA StyleCadirci, M. S. (2025). Non-Parametric Goodness-of-Fit Tests Using Tsallis Entropy Measures. Entropy, 27(12), 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121210