AdaptPest-Net: A Task-Adaptive Network with Graph–Mamba Fusion for Multi-Scale Agricultural Pest Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

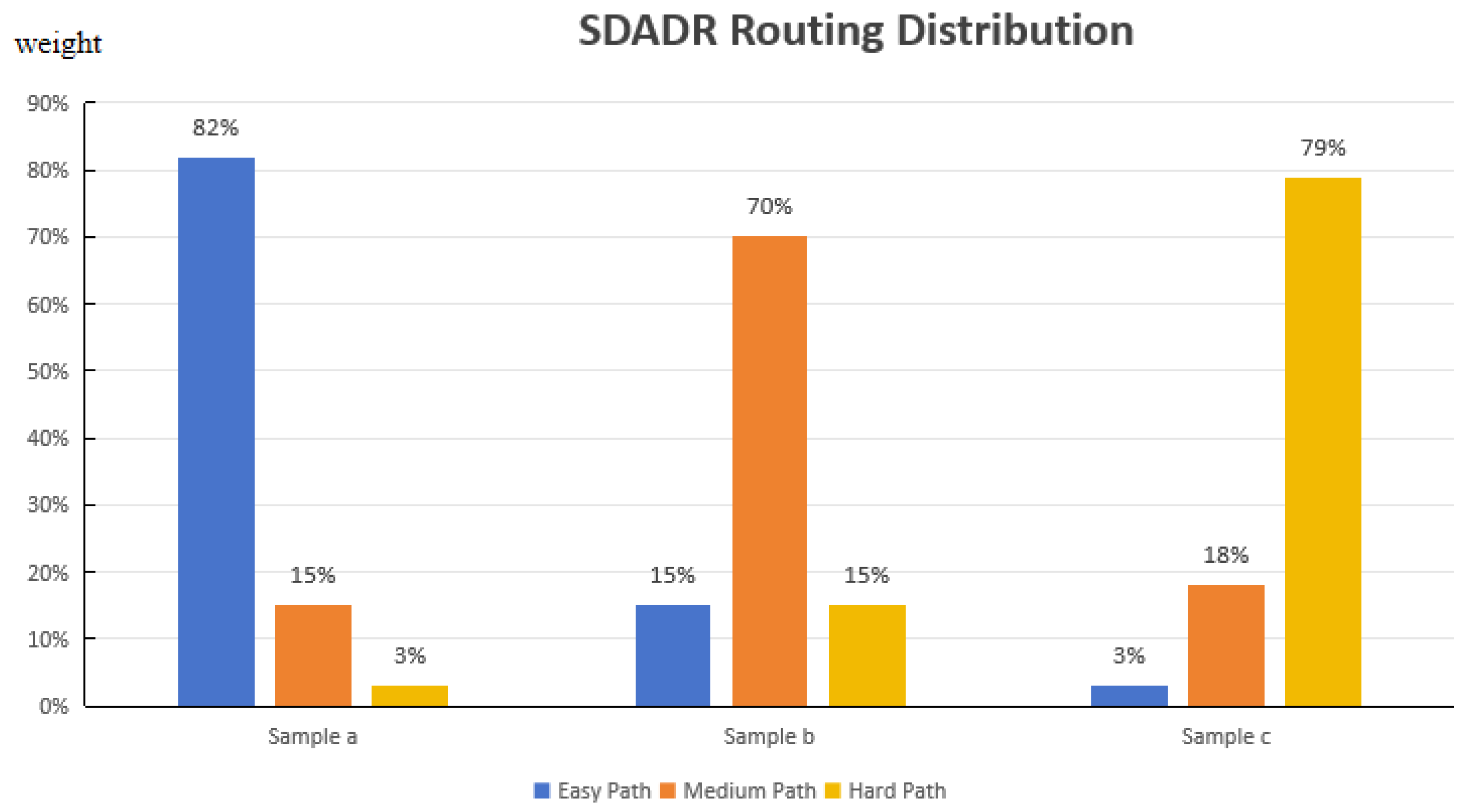

- Sample-Difficulty-Aware Dynamic Routing (SDADR) employs a lightweight difficulty predictor with Gaussian gating to adaptively route samples through shallow, medium, or deep paths. This mechanism matches computational depth to sample complexity, enabling efficient processing of easy samples while allocating sufficient capacity for difficult ones.

- (2)

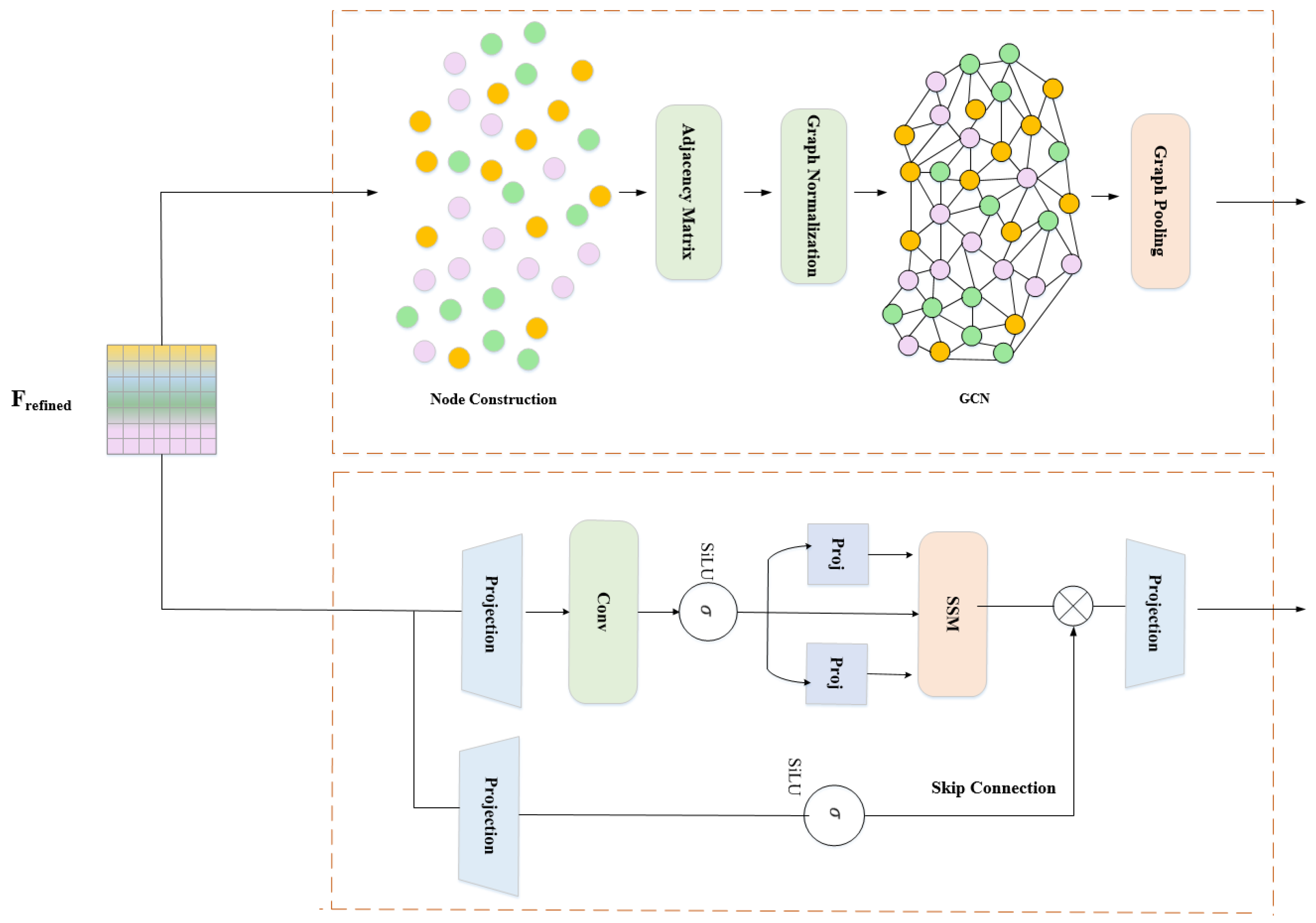

- Graph Convolution-Mamba Fusion (GCMF) captures complementary spatial–temporal information through parallel extraction: a multi-layer GCN with adaptive adjacency models spatial structural relationships via topological message passing, while selective Mamba with input-dependent parameters models temporal feature evolution with content-based filtering. This dual-branch design captures both anatomical connectivity and feature dynamics with linear complexity.

- (3)

- Bidirectional Cross-Modal Attention with Graph Guidance deeply integrates spatial and temporal features through bidirectional attention for mutual enhancement with batch-level knowledge transfer, adaptive gate fusion for sample-specific feature weighting, and graph-guided parameter modulation where spatial topology directly influences temporal state-space dynamics to ensure structure-aware evolution.

2. Related Work

2.1. Pest Image Classification

2.2. State Space Models and Mamba

2.3. Graph Convolutional Networks

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Architecture

3.2. Sample-Difficulty-Aware Dynamic Routing (SDADR)

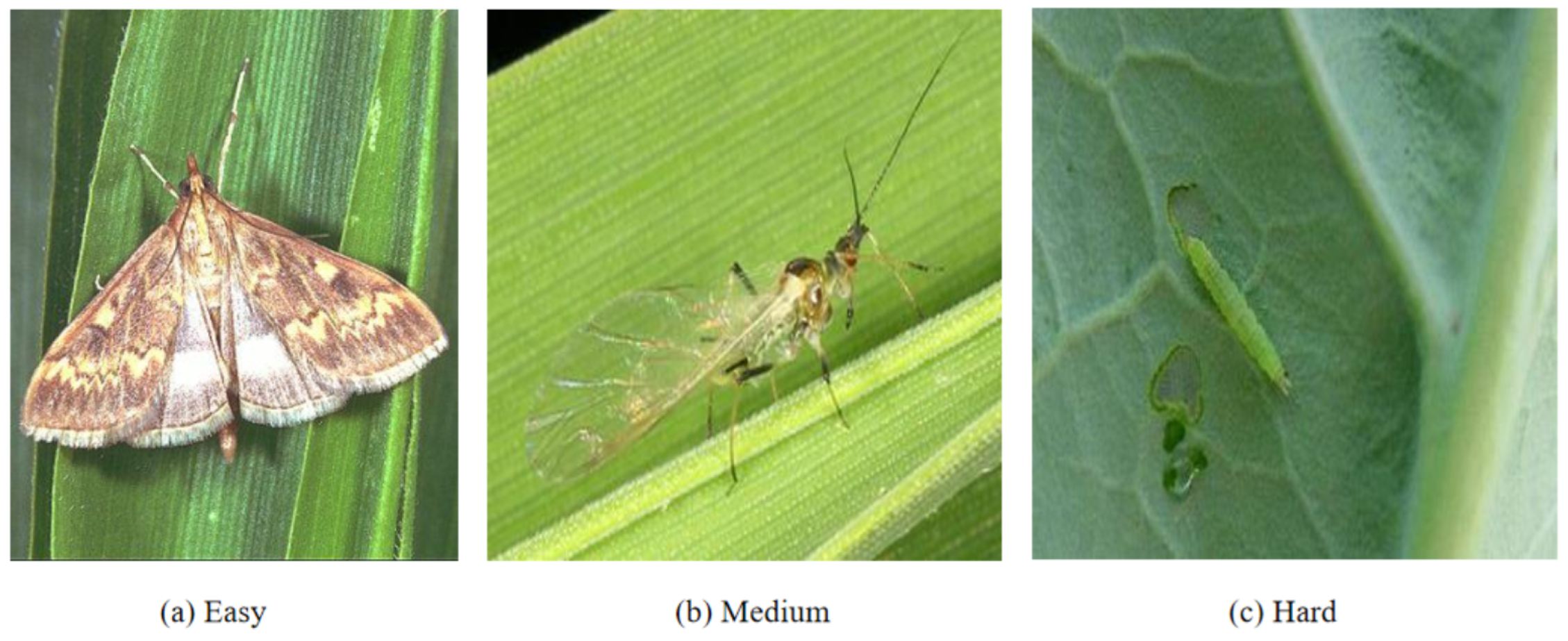

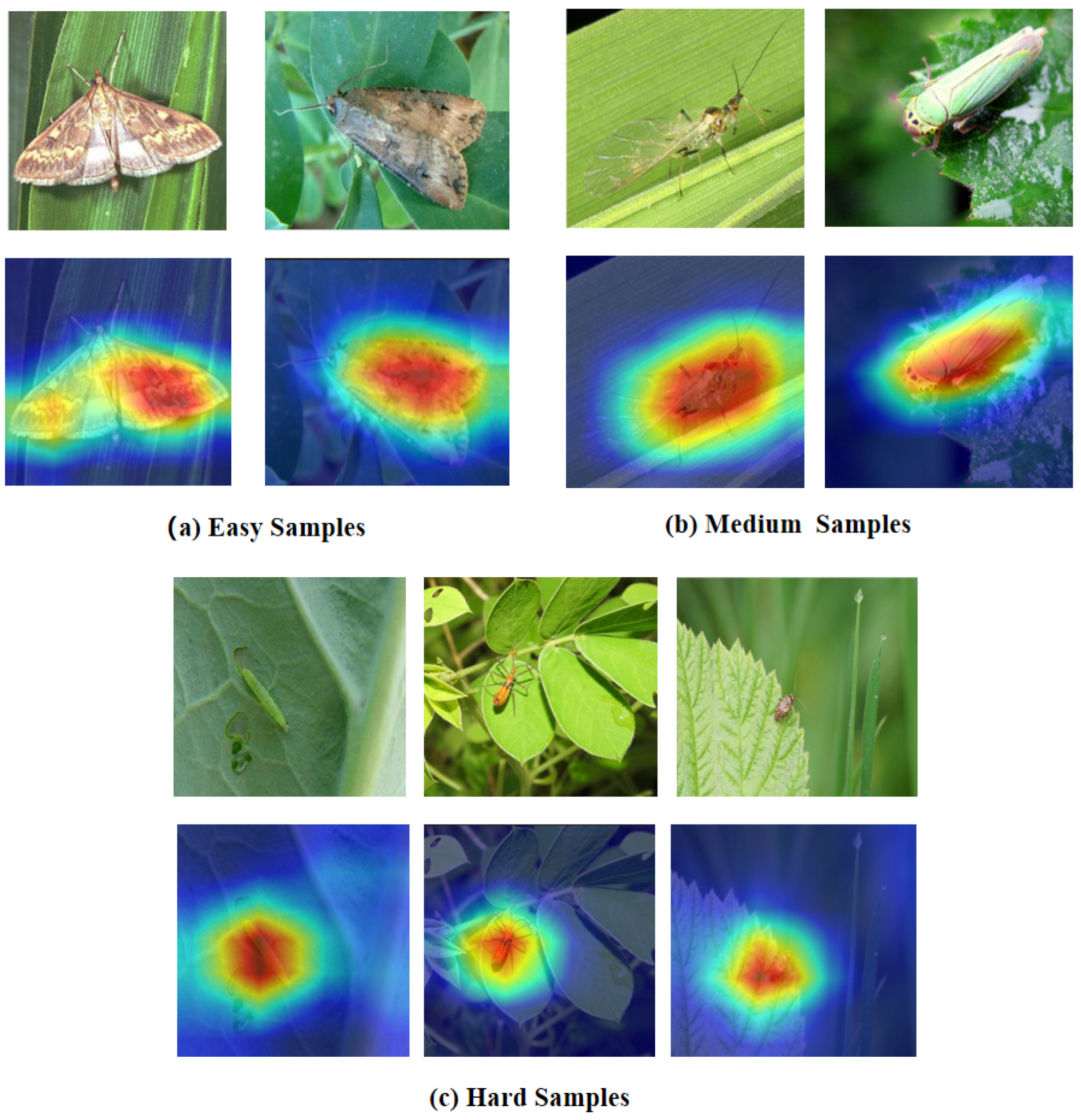

- Easy sample: A 40 mm moth specimen captured on a green leaf background, captured in perfect lighting with no occlusion. The large size, clear boundaries, and simple background make species identification straightforward—even shallow features (edges, basic shapes) suffice.

- Medium sample: A 15 mm small flying insect rests on a leaf surface, featuring semi-transparent wings that reveal delicate membrane structures. This scenario requires intermediate-level feature detection (part boundaries, texture patterns) without needing full semantic understanding.

- Hard sample: A 3 mm heavily camouflaged mantis nymph on foliage, captured in field conditions with motion blur. The small size, complex background, and camouflage demand deep semantic reasoning to distinguish subtle morphological cues from noise.

- Shallow networks (18–34 layers): Efficient but insufficient representational capacity for complex samples.

- Medium networks (50 layers): Balanced but suboptimal for both extremes—over-processes simple samples while under-representing difficult ones.

- Deep networks (101–152 layers): High capacity but paradoxically not always superior, suggesting over-parameterization causes optimization difficulties.

3.2.1. Difficulty Estimation and Gaussian Gating

- : Global average pooling extracts holistic image statistics (56 × 56 → 1 × 1)

- : Progressive dimensionality reduction (256 → 128 → 64 → 1)

- : Sigmoid activation ensures , representing difficulty from easy to hard

3.2.2. Three Adaptive Feature Extraction Paths

- Architecture: Layer2 (4 blocks, stride 2) + Layer3 (2 blocks, stride 2)

- Output:

- Receptive field: Approximately 91 × 91 pixels

- Feature capacity: Extracts low-to-medium level features—edges, basic shapes, coarse textures. Sufficient for large pests with clear boundaries where class-discriminative information resides in simple visual patterns. Limited depth prevents over-fitting to superficial correlations while maintaining effective representation.

- Architecture: Layer2 (4 blocks) + Layer3 (8 blocks)

- Output:

- Receptive field: Approximately 155 × 155 pixels

- Feature capacity: Builds intermediate semantic features—part boundaries, spatial relationships, texture patterns. Captures part-level understanding suitable for moderately complex scenarios: medium-sized pests, moderate occlusion, or textured backgrounds requiring structural analysis beyond basic appearance.

- Architecture: Layer2 (4 blocks) + Layer3 (8 blocks) + Layer4 (6 blocks)

- Output:

- Receptive field: Approximately 219 × 219 pixels (covers entire 224 × 224 image)

- Feature capacity: Learns high-level semantic abstractions through maximum representational depth. Essential for challenging cases—small pests requiring global context integration to distinguish from background, heavy occlusion demanding reasoning about unseen parts, or extreme camouflage requiring semantic understanding of “pest-ness” versus environmental patterns.

- 1.

- Easy path: Emphasizes local patterns and textures—sufficient for pests with distinctive appearance

- 2.

- Medium path: Adds spatial context and part-level semantics—necessary for moderately ambiguous cases

- 3.

- Hard path: Provides global semantic reasoning—critical for fine-grained discrimination under adverse conditions.

- 1.

- Multi-level feature integration: Easy samples leverage coarse-grained features (low abstraction), hard samples utilize fine-grained semantic patterns (high abstraction), boundary cases benefit from balanced mixtures—all dynamically determined by .

- 2.

- Hierarchical complementarity: The weighted combination creates an ensemble effect where shallow features capture salient low-level patterns, medium features add structural context, and deep features provide semantic refinement. For ambiguous samples near decision boundaries, this multi-level representation improves robustness.

- 3.

- Adaptive receptive field: Effective receptive field automatically adjusts—easy path emphasizes local patterns, hard path incorporates global context. This addresses the fundamental challenge that the optimal receptive field varies dramatically across pest scales and complexity levels.

- 4.

- Feature abstraction calibration: By controlling the mixture of shallow/medium/deep features, SDADR effectively modulates semantic abstraction level. Simple classification problems are solved in “feature space” (low abstraction), complex problems in “semantic space” (high abstraction)—matching representation to task requirements.

- 5.

- Differentiability: Gradients flow through all paths, enabling stable end-to-end training without discrete routing decisions.

- 6.

- Robustness: Prediction errors in difficulty estimation are naturally hedged—if d is slightly misestimated, adjacent paths still contribute meaningfully, preventing catastrophic failures.

- Samples consistently classified correctly early (e.g., large beetles on white backgrounds) gradually receive lower d scores, emphasizing the easy path and low-level features

- Samples with persistent errors (e.g., small camouflaged aphids) receive higher d scores, directing them through the hard path for deep semantic processing

- Samples with ambiguous features (e.g., morphologically similar species) maintain medium d scores, benefiting from balanced multi-level feature extraction

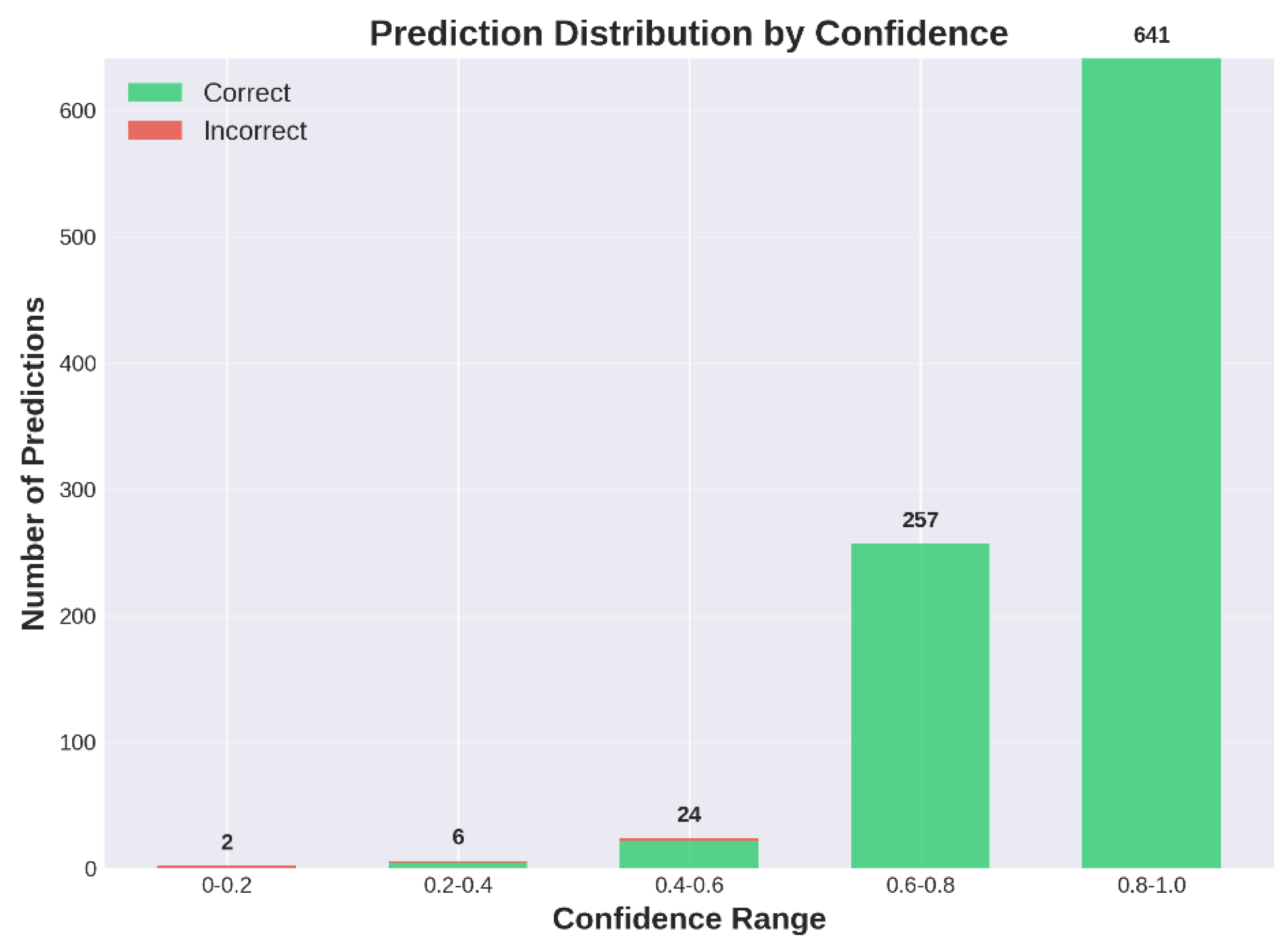

- Size correlation: Small pests receive significantly higher difficulty scores () than large pests (, , Welch’s t-test).

- Background complexity: Pests on complex backgrounds score higher () than simple backgrounds (, ).

- Occlusion level: Heavily occluded samples show elevated scores () versus non-occluded (, ).

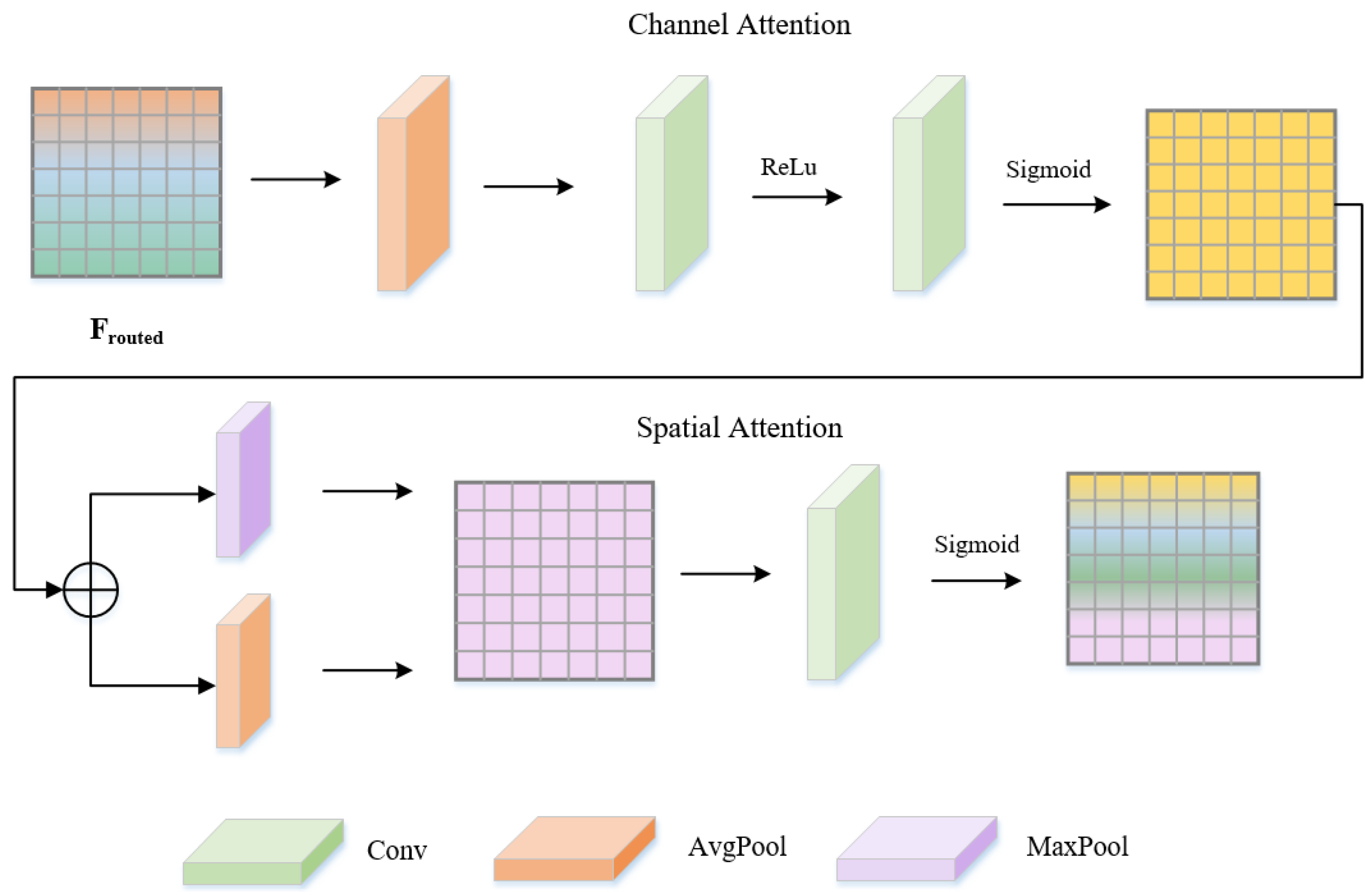

3.3. Dynamic Feature Refinement (DFR)

3.4. Graph Convolution–Mamba Fusion (GCMF)

3.4.1. Graph Branch: Explicit Spatial Structure Modeling

- Similarity term (): Provides inductive bias by connecting nodes with similar features, capturing inherent patterns like bilateral symmetry (left/right wings, antenna pairs) and hierarchical part structure (sub-features within thorax/abdomen cluster together). The lower weight (30%) ensures that similarity does not dominate learned patterns.

- Learned term (): A two-layer MLP (128 → 64 → 1 dimensions with ReLU) learns task-specific connectivity from classification loss. Importantly, this can connect nodes with dissimilar features if they share discriminative importance. For example, head and abdominal features may differ substantially, but their specific combination distinguishes certain species, requiring learned connections beyond similarity.

- Biological interpretation: The adaptive adjacency implicitly discovers pest body topology. Analysis reveals that the learned graph often exhibits structure matching anatomical organization—central “thorax nodes” with high degree connecting to “wing/leg/head/abdomen nodes” peripherally, mirroring actual insect body plans.

- Layer 1: Aggregates 1-hop neighbors. Node i receives messages from directly connected nodes, capturing immediate structural relationships (e.g., thorax connects to adjacent wings, head, abdomen).

- Layer 2: Aggregates 2-hop information through composition. Now node i incorporates messages from neighbors-of-neighbors, modeling extended relationships (e.g., head indirectly receives wing information routed through thorax).

- Layer 3: Captures 3-hop dependencies, providing global receptive field across all 32 nodes. At this depth, information has propagated across the entire graph, enabling holistic structural understanding.

3.4.2. Mamba Branch: Selective Temporal Dynamics Modeling

- : State transition matrix (learned, initialized with HiPPO for optimal memory)

- : Input-dependent discretization step (key innovation)

- : Input gating matrix (input-dependent)

- : Output projection matrix (input-dependent)

- : Skip connection weight (learned)

- : Hidden state at step t (default state dimensions)

- Large : (identity), strongly retaining previous state → emphasizes memory and accumulation

- Small : (zero), resetting state and emphasizing current input → emphasizes new information

- Large clear pests: Early time steps learn complete representation (large ), later steps maintain it

- Small noisy pests: Gradual accumulation across all T steps, with selective gating filtering unreliable low-resolution features

- Occluded pests: Visible parts receive large (retained), occluded regions receive small (discarded)

3.4.3. Bidirectional Cross-Modal Interaction

- : Spatial structural relationships (topological connectivity between feature groups)

- : Temporal feature dynamics (evolution through abstraction levels)

- 1.

- Cross-sample knowledge transfer: Rare-class sample i can attend to features from similar majority-class sample j in the same batch, borrowing structural/temporal patterns

- 2.

- Implicit prototypical learning: Attention automatically computes soft prototypes by aggregating features from multiple similar samples

- 3.

- Robustness to outliers: Outlier samples receive low attention weights from all others, preventing noisy features from contaminating representations.

- Structural grounding for temporal features: Mamba identifies abstract patterns (“elongated textured region”). Graph provides spatial context: “This corresponds to the wing–thorax boundary with specific connectivity.”

- Temporal context for structural features: Graph finds relationships (“antenna strongly connected to head”). Mamba provides evolution context: “This connection strengthens across time, indicating antennae are discriminative.”

- Cross-modal consistency checking: If graph suggests a strong wing–abdomen connection but Mamba shows weak wing activation, this inconsistency signals occlusion/damage, triggering compensatory attention.

- Spatial structure (graph convolution message passing)

- Temporal dynamics (Mamba state evolution)

- Cross-modal enhancement (bidirectional attention)

- Adaptive fusion (learned gating mechanism)

3.5. Classification and Training

- 1.

- Batch-Level Knowledge Transfer (GCMF): The bidirectional cross-modal attention in GCMF operates at the batch level, computing B×B attention score matrices rather than per-sample attention. This design enables implicit knowledge transfer—rare-class samples (<100 training images) can attend to and borrow features from morphologically similar majority-class samples within the same batch. For example, if a rare beetle species shares wing structure with a common beetle, the rare-class sample’s graph features can query the majority-class sample’s well-learned structural patterns through cross-attention. This batch-level interaction acts as implicit few-shot learning, stabilizing rare-class representations.

- 2.

- Focal Loss with Class-Balanced Weighting: The classification loss employs focal loss [41] with class-balanced weighting:where down-weights easy samples, is the training sample count for class c, and inverse square-root weighting balances rare/common classes without over-emphasizing outliers. This prevents the model from ignoring rare classes during optimization.

- 3.

- CutMix Data Augmentation: We apply CutMix [42] with probability 0.5 during training. By randomly mixing image patches and labels from different classes, CutMix effectively synthesizes new training samples for rare classes. For a rare class with 50 samples, CutMix approximately doubles the effective training set by creating mixed samples, mitigating overfitting to limited data.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.4.1. Component Contribution Analysis

- Analysis of Individual Component Contributions. The individual ablation results (Table 5, left) reveal distinct characteristics of each component:

- (1)

- SDADR provides the strongest single-component improvement (+4.5%), demonstrating the fundamental importance of adaptive computation allocation. By dynamically adjusting computational resources based on sample difficulty, SDADR enables the network to focus processing power where it is most needed. Remarkably, this component also reduces FLOPs by 2.9 G (from 7.8 G to 4.9 G), validating its dual benefit of improved accuracy and efficiency.

- (2)

- GCMF contributes +3.2% when added alone, confirming that spatial–temporal feature fusion through graph and Mamba branches provides strong discriminative power. The graph branch captures spatial relationships among pest features, while the Mamba branch models temporal dependencies across image regions. Their combination, even without other enhancements, substantially improves pest classification.

- (3)

- DFR adds +1.9% independently, showing that dynamic feature refinement through attention mechanisms effectively enhances feature quality. By adaptively weighting different feature channels and spatial locations, DFR helps the network focus on the most discriminative pest characteristics.

- Analysis of Incremental Component Interactions. The incremental ablation results (Table 5, right) demonstrate how components work together synergistically. Starting from the baseline (67.3%), each additional component builds upon previous improvements: SDADR establishes the foundation (+4.5%), DFR further refines features (+1.7%), and GCMF’s sub-components (Graph Branch +0.7%, Mamba Branch +0.9%, Bidirectional Attention +1.4%, Adaptive Fusion +1.9%) progressively enhance the model’s discriminative power.

- Analysis of Synergistic Effects. A critical observation from Table 5 is that the full model’s performance gain (+11.1%) exceeds the sum of individual component gains (+9.6%), yielding a synergy bonus of +1.5%. This positive synergy arises from three key interactions:

- (1)

- SDADR enables more effective feature refinement: By allocating appropriate computation to each sample, SDADR ensures that DFR operates on properly processed features, enhancing refinement quality beyond its standalone contribution.

- (2)

- DFR improves GCMF input quality: Refined features provide cleaner inputs to the graph and Mamba branches, enabling more accurate spatial–temporal modeling than GCMF could achieve independently.

- (3)

- GCMF benefits from adaptive computation: The dual-branch fusion mechanism works more effectively when SDADR has already allocated optimal resources, allowing each branch to extract more discriminative patterns.

4.4.2. GCMF Architecture Ablation

- Graph Branch (+0.7%): GCN with adaptive adjacency captures spatial topological relationships. Most effective for medium/large pests where body part structure is clearly visible.

- Mamba Branch (+1.6%): Selective SSM with linear complexity achieves stronger single-branch gains than graph convolution. Input-dependent gating filters noise from low-resolution regions while accumulating reliable signals across temporal steps.

- Simple Concatenation (+2.3%): Combining both branches improves over either alone but lacks true synergy. Features remain in separate modalities without information exchange, limiting complementarity.

- Unidirectional Attention (+3.0–3.1%): Adding one-way cross-attention improves both directions equally. Graph → Mamba allows structural priors to guide temporal modeling; Mamba → Graph injects temporal context into structural representations. However, asymmetric information flow is suboptimal.

- Bidirectional Attention (+3.8%): Simultaneous two-way attention creates true complementarity where each modality enhances the other. Batch-level attention enables cross-sample knowledge transfer, particularly benefiting rare/difficult classes. The +0.7–0.8% gain over the best unidirectional variant validates bidirectional design.

- Adaptive Gate Fusion (+4.9%): Using learned gating to dynamically balance graph and Mamba contributions based on sample characteristics achieves the highest performance. The substantial final gain (+1.1% over bidirectional attention) demonstrates that adaptive sample-specific fusion significantly outperforms fixed-weight combination.

4.4.3. Graph Architecture Design Choices

- Node Count: 32 nodes (64-dim each) achieves optimal balance. Fewer nodes (16) lack capacity for complex morphologies; more nodes (64, 128) fragment features excessively, harming message passing efficiency. The 32-node configuration aligns well with semantic grouping of 2048-dimensional features ().

- Adjacency Type: Pure similarity () captures inherent correlations but misses task-specific patterns; pure learned () is flexible but lacks inductive bias. Mixed (30% similarity + 70% learned) provides strong inductive prior while allowing substantial task adaptation.

- GCN Depth: Three layers achieve optimal receptive field, capturing 1-hop (direct neighbors), 2-hop (neighbors-of-neighbors), and 3-hop (global) relationships. Deeper networks (4–5 layers) suffer from over-smoothing where repeated averaging makes node features too similar, losing discriminative power (–0.3% for 5 layers).

4.4.4. Mamba Temporal Modeling Design

- Architecture Comparison: Mamba achieves the highest accuracy (78.4%) with competitive speed (18 ms). LSTM captures sequences but is slower (22 ms) due to non-parallelizable recurrence and achieves lower accuracy (−0.6%). Transformer models relationships well (+0.4% over LSTM), but O() complexity increases latency (24 ms). Mamba combines benefits: strong modeling like LSTM, parallelizable like Transformer, linear O(L) complexity.

- Sequence Length: T = 8 provides sufficient temporal resolution. Shorter sequences (T = 4, 6) underfit dynamics; longer sequences (T = 12, 16) show diminishing returns (±0.0%) while increasing computation. Eight steps effectively capture feature evolution across abstraction levels without redundancy.

- State Dimension: d_state = 16 balances capacity and efficiency. Smaller states (8) limit expressiveness (–0.4%); larger states (32, 64) provide minimal gains (+0.1%, +0.0%) at 11–33% higher cost. The 16-dimensional hidden state sufficiently encodes temporal dependencies for 2048-channel features.

- Selective Gating: Input-dependent parameters (, , ) contribute +0.6% over fixed parameters. This validates that adaptive discretization based on input features is essential for handling diverse pest morphologies—discriminative features receive large (strong accumulation), noise receives small (quick filtering).

4.4.5. Routing Strategy Comparison

- Hard Routing: Non-differentiable argmax achieves lowest FLOPs (4.2 G) by activating only one path but suffers severe training instability and −5.9% accuracy loss due to discrete decisions preventing gradient flow.

- Uniform Weighting: Equal weights () improve over hard routing through differentiability but do not adapt to difficulty, wasting computation on easy samples while under-allocating to hard ones.

- Linear Weighting: provides basic adaptation, but sharp transitions near boundaries (e.g., d = 0.29 vs. d = 0.31) cause gradient instability during training, limiting performance.

- Gaussian Gating (Ours): with provides smooth, differentiable transitions while maintaining selectivity. The Gaussian shape naturally models gradual difficulty changes, prevents gradient vanishing, and achieves optimal balance: +5.9% over hard routing, +3.6% over uniform, +3.3% over linear.

4.4.6. Sensitivity to Key Hyperparameters

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 50 | |

| Top-1 (%) | 75.8 | 77.2 | 78.4 | 78.3 | 78.1 | 77.6 | 76.9 |

| 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| Top-1 (%) | 78.0 | 78.2 | 78.4 | 78.2 | 77.9 | 77.7 | 77.8 |

4.5. Model Compression for Edge Deployment

4.6. Multi-Task Learning Extension

- Unified Inference Pipeline: Single forward pass produces both classification and localization, eliminating the need for separate detection and classification stages in practical deployment.

- Shared Feature Extraction: SDADR and GCMF modules provide high-quality features for both tasks, achieving better parameter efficiency than training separate models (76 M vs. 56.4 M combined parameters).

- Task Complementarity: Localization loss provides additional supervisory signal that improves feature learning, particularly for occluded or small pests where precise spatial attention is critical.

- Practical Deployment Value: Bounding box predictions enable automated pest counting, density estimation, and spatial distribution mapping—essential capabilities for precision agriculture decision support systems.

4.7. Few-Shot Learning for Rare Pest Species

- Efficient Feature Learning with Limited Data: SDADR’s difficulty-aware routing prevents overfitting by using shallow paths for clear support examples and reserving deep capacity for ambiguous query samples. This adaptive allocation is critical when training data is scarce.

- Structural Pattern Generalization: GCMF’s graph convolution captures spatial relationships (e.g., antenna–head connectivity, wing–thorax structure) that generalize across species. Even with five training samples, the model learns that “insects with long antennae and segmented bodies” share similar graph topology, enabling knowledge transfer.

- Cross-Sample Knowledge Transfer: Bidirectional cross-modal attention’s batch-level interaction allows rare-class samples in support set to borrow features from similar examples in query set (or vice versa), effectively augmenting the limited training signal.

- Robustness to Class Imbalance: Unlike methods relying on large-scale pretraining on balanced datasets, AdaptPest-Net’s episodic training naturally handles imbalance by repeatedly exposing the model to varied class configurations during meta-training.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Edge Device Deployment: Although dynamic routing reduces computation, the full model (48.2 M parameters, 192 MB FP32) presents challenges for resource-constrained agricultural devices. The model requires 80–120 ms inference on typical edge platforms (Jetson Nano, mobile phones), exceeding real-time requirements (<50 ms). Memory footprint (192 MB) and power consumption limit deployment on low-cost IoT sensors and solar-powered field devices. Future work will pursue model compression through:

- Quantization: Our preliminary INT8 experiments achieve 4× size reduction (192 MB to 48 MB) with −0.8% accuracy loss. Future INT4 and mixed-precision strategies could enable further compression.

- Knowledge distillation: Train lightweight student models (MobileNetV3, EfficientNet-Lite) targeting 3–5× speedup with <2% accuracy drop.

- Hardware-aware NAS: Discover optimal architectures for target platforms, jointly optimizing accuracy, latency, and power under device constraints.

- Structured pruning: Our initial 30% channel pruning achieves 22% parameter reduction with −1.2% accuracy loss; iterative pruning could reach 40–50% compression.

- (2)

- Domain Adaptation: Training on laboratory images creates gaps with field deployment. Models struggle with motion blur, lighting extremes, occlusion, lifecycle stage variations, and geographic morphological differences. Future research will apply unsupervised domain adaptation, synthetic corruption augmentation, lifecycle-aware modeling, and test-time adaptation for continuous field learning.

- (3)

- Multi-Task Integration: Current classification-only architecture lacks integrated detection, counting, damage assessment, and treatment recommendation capabilities required for practical applications. Future work will develop unified multi-task frameworks and explainable AI mechanisms for agricultural decision support systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, X.; Zhan, C.; Lai, Y.K.; Cheng, M.M.; Yang, J. IP102: A large-scale benchmark dataset for insect pest recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 8787–8796. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_CVPR_2019/html/Wu_IP102_A_Large-Scale_Benchmark_Dataset_for_Insect_Pest_Recognition_CVPR_2019_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yue, Y. Pest identification via deep residual learning in complex background. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B. Plant disease detection and classification by deep learning—A review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 56683–56698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akundi, A.; Reyna, M. A machine vision based automated quality control system for product dimensional analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 185, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Dong, W.; Li, X.; Chen, P.; Tang, J. Multi-level learning features for automatic classification of field crop pests. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 152, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbedo, J.G.A. Digital image processing techniques for detecting, quantifying and classifying plant diseases. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Chan, C.S.; Wilkin, P.; Remagnino, P. How deep learning extracts and learns leaf features for plant classification. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Yu, R. Research on insect pest image detection and recognition based on bio-inspired methods. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 169, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; Volume 25, pp. 1097–1105. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2012/hash/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Abstract.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2016/html/He_Deep_Residual_Learning_CVPR_2016_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2017/html/Huang_Densely_Connected_Convolutional_CVPR_2017_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Li, W.; Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Xie, C. Automatic localization and count of agricultural crop pests based on an improved deep learning pipeline. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollis, E.; Maia, H.; Pedrini, H.; Avila, S. Weakly supervised attention-based models using activation maps for citrus mite and insect pest classification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 195, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N. Pest recognition based on multi-image feature localization and adaptive filtering fusion. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1282212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, L.; Maguolo, G.; Pancino, F. Insect pest image detection and recognition based on bio-inspired methods. Ecol. Inform. 2020, 57, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. Available online: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/tan19a.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2022/html/Liu_A_ConvNet_for_the_2020s_CVPR_2022_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Devi, R.S.; Kumar, V.R.; Sivakumar, P. EfficientNetV2 Model for Plant Disease Classification and Pest Recognition. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=YicbFdNTTy (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/ICCV2021/html/Liu_Swin_Transformer_Hierarchical_Vision_Transformer_Using_Shifted_Windows_ICCV_2021_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Xia, Z.; Pan, X.; Song, S.; Li, L.E.; Huang, G. Vision transformer with deformable attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 4794–4803. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2022/html/Xia_Vision_Transformer_With_Deformable_Attention_CVPR_2022_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ullah, N.; Khan, J.A.; Alharbi, L.A.; Ahmad, J.; Rehman, A.U.; Kim, S. An efficient approach for crops pests recognition and classification based on novel DeepPestNet deep learning model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 73019–73032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 25–29 April 2022; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=uYLFoz1vlAC (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Smith, J.T.H.; Warrington, A.; Linderman, S.W. Simplified state space layers for sequence modeling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=Ai8Hw3AXqks (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Fu, D.Y.; Dao, T.; Saab, K.K.; Thomas, A.W.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Hungry hungry hippos: Towards language modeling with state space models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision mamba: Efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10166. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.; Li, Z. MedMamba: Vision mamba for medical image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y. VideoMamba: State space model for efficient video understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.06977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Lai, Z.; Zhou, Y. InsectMamba: Insect pest classification with state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=SJU4ayYgl (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30, pp. 1024–1034. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2017/hash/5dd9db5e033da9c6fb5ba83c7a7ebea9-Abstract.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=rJXMpikCZ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32, pp. 7444–7452. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/12328 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Q.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Weighted feature fusion of convolutional neural network and graph attention network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, X. Multilayer spectral–spatial graphs for label noisy robust hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 33, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossoun, K.K.H.; Ying, X. A graph neural network approach for early plant disease detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Mining and Big Data (DMBD), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 13–17 December 2024; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 254–265. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-7175-5_21 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yang, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K. Prediction of corn variety yield with attribute-missing data via graph neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_iccv_2017/html/Lin_Focal_Loss_for_ICCV_2017_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Yun, S.; Han, D.; Oh, S.J.; Chun, S.; Choe, J.; Yoo, Y. CutMix: Regularization Strategy to Train Strong Classifiers with Localizable Features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6023–6032. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_ICCV_2019/html/Yun_CutMix_Regularization_Strategy_to_Train_Strong_Classifiers_With_Localizable_Features_ICCV_2019_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Randaugment: Practical automated data augmentation with a reduced search space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 702–703. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_CVPRW_2020/html/w40/Cubuk_Randaugment_Practical_Automated_Data_Augmentation_With_a_Reduced_Search_Space_CVPRW_2020_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, X.; Peng, H.; Zheng, N.; Yang, Y.; Hu, H.; Yuan, Y. EfficientViT: Memory efficient vision transformer with cascaded group attention. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14420–14430. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2023/html/Liu_EfficientViT_Memory_Efficient_Vision_Transformer_With_Cascaded_Group_Attention_CVPR_2023_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, F.; Zheng, X.; Deng, W.; Ma, H.; Su, X.; Wu, L. Integrating Deformable CNN and Attention Mechanism into Multi-Scale Graph Neural Network for Few-Shot Image Classification. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Z. A lightweight model for efficient identification of plant diseases and pests based on deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, C.; Brindha, M. Visual regenerative fusion network for pest recognition. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 2867–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, C. Genetic algorithm-based hyperparameter optimization of deep learning models for PM2.5 time-series prediction. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 2959–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liang, S.; Bi, N.; Tan, J. Attention embedding ResNet for pest classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence (PRAI), Paris, France, 1–3 June 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Chen, J.; Luo, T.; Long, T.; Wang, H. Classification of crop pests based on multi-scale feature fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 194, 106736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, G.; Li, C.; He, Y. Recognizing pests in field-based images by combining spatial and channel attention mechanism. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162448–162459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, M. A CNN-Transformer Hybrid Framework for Multi-Label Predator–Prey Detection in Agricultural Fields. Sensors 2025, 25, 4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Nagasubramanian, K.; Elango, D.; Carroll, M.E.; Abel, C.A.; Nair, A.; Mueller, D.S.; O’Neal, M.E.; Singh, A.K.; Sarkar, S.; et al. Self-supervised learning improves classification of agriculturally important insect pests in plants. Plant Phenome J. 2023, 6, e20079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Deng, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Hao, G. Aa-trans: Core attention aggregating transformer with information entropy selector for fine-grained visual classification. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 140, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lau, R.W.H. BiFormer: Vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 10323–10333. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2023/html/Zhu_BiFormer_Vision_Transformer_With_Bi-Level_Routing_Attention_CVPR_2023_paper.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, B.; Zhan, C.; Guo, C.; Liu, X.; Ruan, S. Efficient Remote Sensing Image Classification Using the Novel STConvNeXt Convolutional Network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ye, L.; Xiao, Z. Lightweight Vision Transformer with Window and Spatial Attention for Food Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.18692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, E.; Erbay, H.; Varçın, F. Crop pest classification with a genetic algorithm-based weighted ensemble of deep convolutional neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, L.; Maguolo, G.; Paci, M. High performing ensemble of convolutional neural networks for insect pest image detection. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 67, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenmozhi, K.; Reddy, U.S. Crop pest classification based on deep convolutional neural network and transfer learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 164, 104906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallée, L.; Lisson, C.S.; Beer, M.; Götz, M. Hierarchical Vision Transformer with Prototypes for Interpretable Medical Image Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Deng, Z. Fine-grained crop pest classification based on multi-scale feature fusion and mixed attention mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1500571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, J.; Swersky, K.; Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/6996-prototypical-networks-for-few-shot-learning (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1126–1135. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v70/finn17a.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| Resolution Range | Samples (%) | Accuracy (%) | Quality Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| >1024 × 1024 | 23.5 | 82.3 | High |

| 512–1024 | 48.2 | 78.4 | Medium |

| <512 | 28.3 | 71.2 | Low |

| Method | Params | Peak Mem. | Mem./Param | Jetson AGX | Jetson Nano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M) | (GB) | (MB/M) | Compatible? | Compatible? | |

| ResNet-101 [11] | 44.5 | 5.2 | 116.9 | ✓ | × |

| Swin-Base [21] | 88.0 | 7.8 | 88.6 | ✓ | × |

| InsectMamba [32] | 35.8 | 4.1 | 114.5 | ✓ | ✓ (batch = 8) |

| EfficientViT [44] | 33.2 | 4.6 | 138.6 | ✓ | ✓ (batch = 8) |

| CA-MFE-GNN [45] | 57.9 | 6.3 | 108.8 | ✓ | × |

| AdaptPest-Net (Ours) | 48.2 | 3.8 | 78.8 | ✓ | ✓ (batch = 16) |

| Method | Acc. (%) | F1 (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 [1] | 49.50 | 40.10 | 25.6 | 4.09 |

| ResNet-101 [11] | 67.30 | - | 44.5 | 7.80 |

| DenseNet-161 [12] | 68.50 | - | 28.7 | 7.70 |

| EfficientNet-B4 [17] | 70.40 | - | 19.3 | 4.20 |

| EfficientNet-V2-S [46] | 70.00 | - | 20.3 | 2.80 |

| VRFNET [47] | 68.34 | 68.34 | 5.6 | 1.20 |

| IRNV2 [48] | 71.84 | 64.06 | 60.4 | - |

| AM-ResNet [49] | 72.99 | - | 22.0 | 10.20 |

| PestNet [50] | 73.90 | 73.60 | - | - |

| MANet [51] | 73.29 | - | - | 5.45 |

| ViT-Base [20] | 71.20 | - | 86.6 | 17.60 |

| Swin-Base [21] | 72.80 | - | 88.0 | 15.40 |

| CNN+Transformer [52] | 74.89 | - | 28.3 | 4.50 |

| FRCF+LSMAE [53] | 74.69 | 74.36 | 32.3 | 5.20 |

| AA-Trans [54] | 75.00 | - | - | - |

| BiFormer [55] | 75.23 | 74.89 | 35.8 | 4.60 |

| STConvNeXt [56] | 76.28 | 75.85 | 24.8 | 3.15 |

| EfficientViT [44] | 75.67 | 75.34 | 33.2 | 4.40 |

| Lightweight-ViT [57] | 76.92 | 76.51 | 18.3 | 2.87 |

| CA-MFE-GNN [45] | 77.58 | 77.12 | 57.9 | 8.34 |

| Vision Mamba [28] | 70.50 | - | 32.1 | 5.20 |

| InsectMamba [32] | 73.10 | - | 35.8 | 6.10 |

| GAEnsemble [58] | 67.13 | 65.76 | 25.4 | 6.20 |

| EnseCNN [59] | 74.11 | 72.90 | - | - |

| AdaptPest-Net (Ours) | 78.40 | 78.09 | 48.2 | 4.70 |

| Method | Acc. (%) | F1 (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLLCNN [5] | 89.30 | - | 22.0 | 10.2 |

| DCNN [60] | 95.97 | - | 24.5 | 4.7 |

| SMPEnsemble [58] | 98.37 | 98.38 | 25.4 | 6.2 |

| GAEnsemble [58] | 98.81 | 98.81 | - | - |

| STConvNeXt [56] | 98.95 | 98.89 | 24.8 | 3.15 |

| VRFNet [47] | 99.12 | 99.12 | 5.6 | 1.2 |

| HierViT [61] | 99.08 | 99.02 | 71.5 | 14.52 |

| Lightweight-ViT [57] | 99.18 | 99.13 | 18.3 | 2.87 |

| InsectMamba [32] | 99.18 | 99.12 | 35.8 | 6.1 |

| CA-MFE-GNN [45] | 99.28 | 99.23 | 57.9 | 8.34 |

| Pest-ConFormer [62] | 99.51 | 99.50 | 19.8 | 3.9 |

| Vision Mamba [28] | 98.45 | 98.38 | 32.1 | 5.2 |

| VMamba [29] | 98.72 | 98.65 | 44.3 | 6.5 |

| IRNV2 [48] | 99.69 | 99.86 | 23.6 | 5.8 |

| AdaptPest-Net (Ours) | 99.85 | 99.74 | 48.2 | 4.7 |

| Individual Component | Incremental Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Acc. | FLOPs | Configuration | Acc. | FLOPs |

| (%) | (G) | (%) | (G) | ||

| Baseline | 67.3 | 7.8 | Baseline | 67.3 | 7.8 |

| +SDADR only | 71.8 | 4.9 | +SDADR | 71.8 | 4.9 |

| +DFR only | 69.2 | 8.1 | +DFR | 73.5 | 5.1 |

| +GCMF only | 70.5 | 8.5 | +Graph Branch | 74.2 | 5.4 |

| +Mamba Branch | 75.1 | 5.2 | |||

| +Bidir. Attention | 76.5 | 4.9 | |||

| +Adaptive Fusion | 78.4 | 4.7 | |||

| Configuration | Top-1 (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No GCMF (DFR only) | 73.5 | 33.7 | 5.1 |

| +Graph Branch only | 74.2 (+0.7) | 34.0 | 5.4 |

| +Mamba Branch only | 75.1 (+1.6) | 42.2 | 5.2 |

| +Both (concatenation) | 75.8 (+2.3) | 46.9 | 5.5 |

| +Unidirectional Attn (G → M) | 76.5 (+3.0) | 47.8 | 4.8 |

| +Unidirectional Attn (M → G) | 76.6 (+3.1) | 47.8 | 4.8 |

| +Bidirectional Attention | 77.3 (+3.8) | 48.2 | 4.8 |

| +Adaptive Gate Fusion | 78.4 (+4.9) | 48.2 | 4.7 |

| Configuration | Top-1 (%) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Nodes | ||

| 16 nodes (128-dim each) | 77.9 | 4.6 |

| 32 nodes (64-dim each) | 78.4 | 4.7 |

| 64 nodes (32-dim each) | 78.2 | 5.2 |

| 128 nodes (16-dim each) | 77.8 | 5.8 |

| Adjacency Matrix Type | ||

| Similarity only () | 77.8 | 4.7 |

| Learned only () | 78.0 | 4.7 |

| Mixed () | 78.2 | 4.7 |

| Mixed () | 78.4 | 4.7 |

| GCN Depth | ||

| 1 layer | 77.5 | 4.3 |

| 2 layers | 78.1 | 4.6 |

| 3 layers | 78.4 | 4.7 |

| 4 layers | 77.8 | 5.1 |

| 5 layers | 78.0 | 5.4 |

| Configuration | Top-1 (%) | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Architectures | ||

| No temporal modeling | 77.1 | 17 |

| Simple repetition averaging | 77.3 | 17 |

| LSTM (hidden = 256) | 77.8 | 22 |

| Transformer (2 layers, 4 heads) | 78.0 | 24 |

| Mamba (d_state = 16) | 78.4 | 18 |

| Sequence Length T | ||

| T = 4 | 77.9 | 17 |

| T = 6 | 78.2 | 17 |

| T = 8 | 78.4 | 18 |

| T = 12 | 78.4 | 19 |

| T = 16 | 78.3 | 21 |

| State Dimension d_state | ||

| d_state = 8 | 78.0 | 17 |

| d_state = 16 | 78.4 | 18 |

| d_state = 32 | 78.5 | 20 |

| d_state = 64 | 78.4 | 24 |

| Selective Gating | ||

| Fixed parameters (no selection) | 77.8 | 18 |

| Input-dependent (selective) | 78.4 | 18 |

| Routing Strategy | Top-1 (%) | Avg FLOPs (G) | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed depth (18 layers) | 67.3 | 7.8 | N/A |

| Hard routing (argmax) | 72.5 | 4.2 | Poor |

| Soft routing (uniform ) | 74.8 | 5.3 | Good |

| Soft routing (linear) | 75.1 | 5.1 | Moderate |

| Soft routing (Gaussian) | 78.4 | 4.7 | Excellent |

| Strategy | Rare Cls | Majority Cls | Overall | Imbalance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc. (%) | Acc. (%) | Acc. (%) | Gap (%) | |

| Baseline (uniform weighting) | 58.7 | 84.2 | 75.2 | 25.5 |

| +Focal Loss only | 62.5 | 83.8 | 76.4 | 21.3 |

| +Batch-level transfer only | 63.2 | 84.5 | 77.0 | 21.3 |

| +CutMix only | 61.8 | 84.1 | 76.5 | 22.3 |

| +All three mechanisms | 65.5 | 86.9 | 78.4 | 21.4 |

| Method | Acc. | Size | Params | FLOPs | Jetson Nano | Compression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (MB) | (M) | (G) | Latency (ms) | Ratio | |

| FP32 baseline | 78.4 | 192 | 48.2 | 4.7 | 18 | 1.0× |

| INT8 quantization | 77.6 | 48 | 48.2 | 4.7 | 13 | 4.0× |

| Pruning (30%) | 77.2 | 150 | 37.6 | 3.9 | 15 | 1.3× |

| INT8 + Pruning | 77.0 | 60 | 37.6 | 3.9 | 11 | 3.2× |

| Model Variant | Cls. Acc. | mAP@0.5 | Params | FLOPs | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (M) | (G) | Time (ms) | |

| Classification-only | 78.4 | - | 48.2 | 4.7 | 18 |

| Multi-task (joint) | 76.8 | 72.3 | 56.4 | 5.9 | 24 |

| Task-specific performance breakdown: | |||||

| Small pests (<5 mm) | 80.5 | 68.2 | - | - | - |

| Medium pests (5–20 mm) | 77.1 | 73.8 | - | - | - |

| Large pests (>20 mm) | 75.2 | 74.9 | - | - | - |

| Method | 5-Way-5-Shot | 5-Way-10-Shot | 5-Way-20-Shot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acc. (%) | Acc. (%) | Acc. (%) | |

| Fine-tuning baseline | 48.2 ± 3.1 | 58.9 ± 2.8 | 67.3 ± 2.2 |

| ProtoNet | 55.7 ± 2.9 | 64.5 ± 2.5 | 70.7 ± 2.1 |

| MAML | 57.3 ± 3.2 | 66.2 ± 2.7 | 72.4 ± 2.3 |

| AdaptPest-Net (Ours) | 64.2 ± 2.6 | 71.8 ± 2.3 | 76.5 ± 2.0 |

| Component ablation in 5-way-5-shot: | |||

| Without SDADR | 58.5 ± 2.9 | - | - |

| Without GCMF | 60.3 ± 2.8 | - | - |

| Without episodic training | 55.1 ± 3.1 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, J.; Yang, W.; Li, C.; Feng, Z. AdaptPest-Net: A Task-Adaptive Network with Graph–Mamba Fusion for Multi-Scale Agricultural Pest Recognition. Entropy 2025, 27, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121211

Zou J, Yang W, Li C, Feng Z. AdaptPest-Net: A Task-Adaptive Network with Graph–Mamba Fusion for Multi-Scale Agricultural Pest Recognition. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121211

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Jixiang, Wenzhong Yang, Chuanxiang Li, and Zhishan Feng. 2025. "AdaptPest-Net: A Task-Adaptive Network with Graph–Mamba Fusion for Multi-Scale Agricultural Pest Recognition" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121211

APA StyleZou, J., Yang, W., Li, C., & Feng, Z. (2025). AdaptPest-Net: A Task-Adaptive Network with Graph–Mamba Fusion for Multi-Scale Agricultural Pest Recognition. Entropy, 27(12), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121211