Wealth Distribution Under Power Trading Frequencies and Transitions of Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

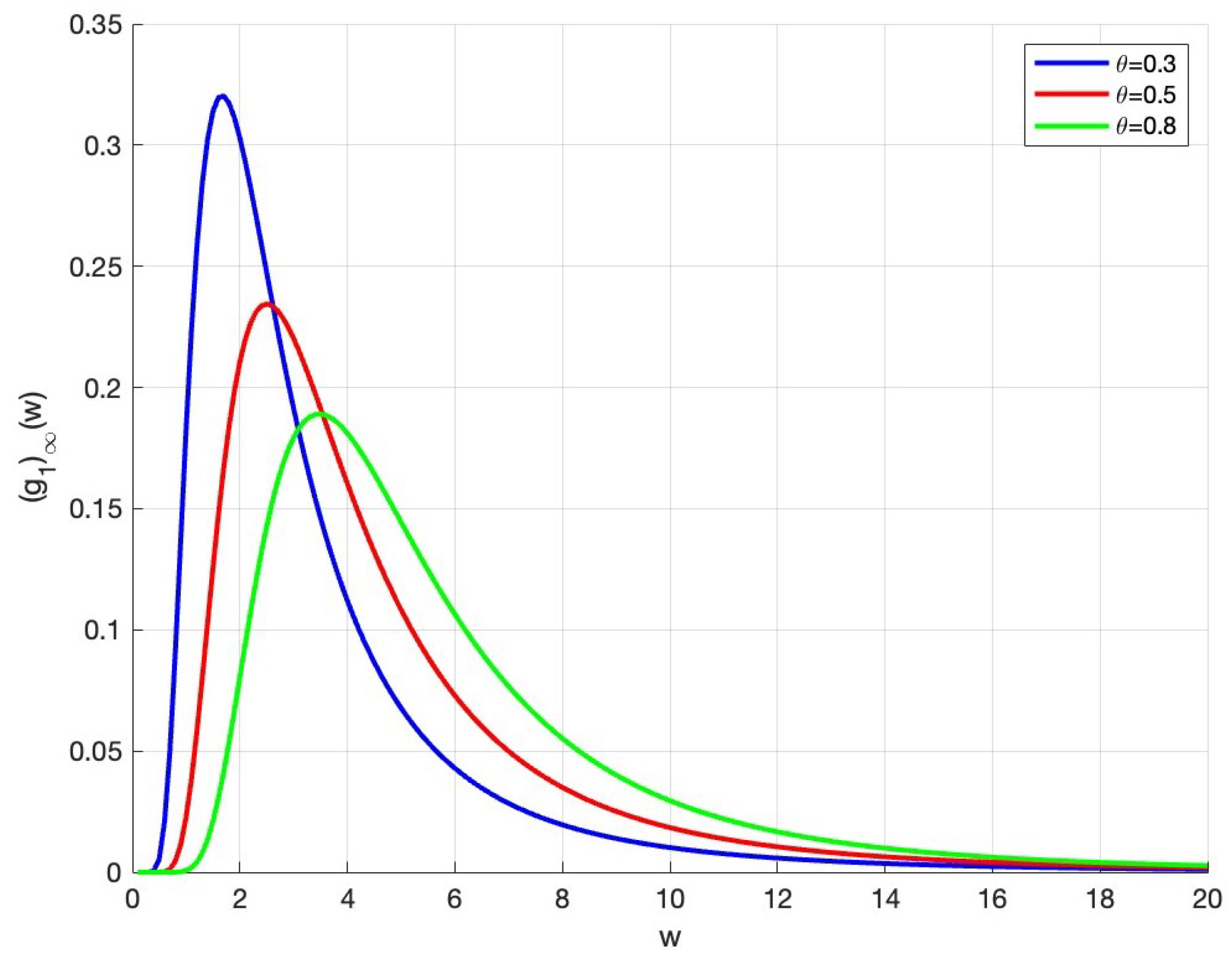

- Inspired by the work in Furioli et al. [30], we choose the power collision kernels and (w indicates the wealth of agents, and represent the intensities of trading willingness of the agents in counties 1 and 2, respectively) that differ from the constant collision kernel in Bisi [35]. The power collision kernels ensure that the agent with zero wealth does not participate in the transaction, and the transaction frequency depends on the agent’s wealth level and the trading willingness.

- (ii)

- The conclusion in Bisi [35] illustrates that the steady-state wealth distribution contains a Pareto tail, which depends on the trading rate. However, in our steady-state solution, the Pareto index is jointly determined by the trading rate and the intensity of trading willingness.

- (iii)

- Assuming that there is only one group in the market when , Bisi [35] obtains the wealth distribution of agents in this group, which is a unimodal distribution. In this paper, we follow the idea in Zhang et al. [28] and suppose that the distribution functions of agents in two countries are linearly correlated as and find the steady-state distribution of the total wealth, which shows a bimodal pattern.

2. Wealth Dynamics in International Trade

3. Boltzmann Equations with Interaction and Transfer Operators

4. Continuous Trading Limit and Fokker–Planck Equations

4.1. Solvable Case 1

4.2. Solvable Case 2

5. Numerical Experiments

5.1. Test 1: Analysis of Influencing Factors of Steady-State Wealth Distribution

5.2. Test 2: The Bimodal Characteristics of the Total Wealth Distribution

6. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maxwell, J.C. On the dynamical theory of gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 1867, 157, 49–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boltzmann, L. Weitere studien über das wärmegleichgewicht unter gasmolekülen. In Kinetische Theorie II. WTB Wissenschaftliche Taschenbücher; Vieweg+Teubner: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1970; pp. 115–225. [Google Scholar]

- Risken, H. The Fokker–Planck equation. In The Fokker-Planck Equation; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, C. On a new class of weak solutions to the spatially homogeneous Boltzmann and Landau equations. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1998, 143, 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, C. A review of mathematical topics in collisional kinetic theory. In Handbook of Mathematical Fluid Dynamics; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Herty, M.; Pareschi, L. Fokker-Planck asymptotics for traffic flow models. Kinet. Relat. Mod. 2010, 3, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I.; Andrews, F.C. A Boltzmann-like approach for traffic flow. Oper. Res. 1960, 8, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppo, G.; Semplice, M.; Tosin, A.; Visconti, G. Kinetic models for traffic flow resulting in a reduced space of microscopic velocities. Kinet. Relat. Mod. 2017, 10, 823–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, E.; Pareschi, L. Mean field mutation dynamics and the continuous Luria-Delbrück distribution. Math. Biosci. 2012, 240, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscani, G. A kinetic description of mutation process in bacteria. Kinet. Relat. Mod. 2013, 6, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albi, G.; Pareschi, L.; Zanella, M. Boltzmann-type control of opinion consensus through leaders. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20140138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albi, G.; Herty, M.; Pareschi, L. Kinetic description of optimal control problems and applications to opinion consensus. Commun. Math. Sci. 2015, 13, 1407–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albi, G.; Pareschi, L.; Zanella, M. Boltzmann games in heterogeneous consensus dynamics. J. Stat. Phys. 2019, 175, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düring, B.; Wright, O. On a kinetic opinion formation model for preelection polling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscani, G. Kinetic models of opinion formation. Commun. Math. Sci. 2006, 4, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Gans, N.; Mandelbaum, A.; Sakov, A.; Shen, H.; Zeltyn, S.; Zhao, L. Statistical analysis of a telephone call center: A queueing-science perspective. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2005, 100, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, M.; Gicquel, C.; Jouini, O. A joint chance-constrained programming approach for call center workforce scheduling under uncertain call arrival forecasts. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 96, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.; Moiseev, A.; Moiseeva, S. Mathematical model of call center in the form of multi-server queueing system. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareto, V. Cours d’Economie Politique; Macmillan: Lausanne, Switzerland, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, D.; Toscani, G. On steady distributions of kinetic models of conservative economies. J. Stat. Phys. 2008, 130, 1087–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareschi, L.; Zanella, M. Structure preserving schemes for nonlinear Fokker-Planck equations and applications. J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 74, 1575–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, S.; Pareschi, L.; Toscani, G. On a kinetic model for a simple market economy. J. Stat. Phys. 2005, 120, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düring, B.; Toscani, G. International and domestic trading and wealth distribution. Commun. Math. Sci. 2008, 6, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisi, M.; Spiga, G.; Toscani, G. Kinetic models of conservative economies with wealth redistribution. Commun. Math. Sci. 2009, 7, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareschi, L.; Toscani, G. Wealth distribution and collective knowledge: A Boltzmann approach. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20130396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisi, M. Some kinetic models for a market economy. Boll. Unione Mat. Ital. 2017, 10, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimarco, G.; Pareschi, L.; Toscani, G.; Zanella, M. Wealth distribution under the spread of infectious diseases. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.T.; Lai, S.Y.; Zhao, M.F. On the analysis of wealth distribution in the context of infectious diseases. Entropy 2024, 26, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.M.; Wang, D.X. A kinetic description of the goods exchange market allowing transfer of agents. Chin. Phys. B 2025, 34, 030502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furioli, G.; Pulvirenti, A.; Terraneo, E.; Toscani, G. Non-Maxwellian kinetic equations modeling the dynamics of wealth distribution. Math. Mod. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2020, 30, 685–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballante, E.; Bardelli, C.; Zanella, M.; Figini, S.; Toscani, G. Economic segregation under the action of trading uncertainties. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimarco, G.; Toscani, G. Social climbing and Amoroso distribution. Math. Mod. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2020, 30, 2229–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Lai, S.Y. Wealth distribution involving psychological traits and non-Maxwellian collision kernel. Entropy 2025, 27, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Liu, M.; Lai, S.Y. On the study of wealth distribution with non-Maxwellian collision kernels and variable trading propensity. Math.Comput. Appl. 2025, 30, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisi, M. Kinetic model for international trade allowing transfer of individuals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter Symbol | Parameter Meaning | Range of Values |

|---|---|---|

| The intensity of trading willingness of agents in country 1. | ||

| The intensity of trading willingness of agents in country 2. | ||

| The trading rate of agents. | ||

| The expectation of the square of a random variable. | ||

| The probability of an agent transferring from country 1 to country 2. | ||

| The probability of an agent transferring from country 2 to country 1. | ||

| D | The ratio of the steady-state wealth distributions of the two countries of agents. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, R.; Lai, S.; Zhou, X. Wealth Distribution Under Power Trading Frequencies and Transitions of Agents. Entropy 2025, 27, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121209

Sun R, Lai S, Zhou X. Wealth Distribution Under Power Trading Frequencies and Transitions of Agents. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121209

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Rongmei, Shaoyong Lai, and Xia Zhou. 2025. "Wealth Distribution Under Power Trading Frequencies and Transitions of Agents" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121209

APA StyleSun, R., Lai, S., & Zhou, X. (2025). Wealth Distribution Under Power Trading Frequencies and Transitions of Agents. Entropy, 27(12), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121209