Argon Ion Treatment of Multi-Material Layered Surface-Electrode Traps for Noise Mitigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

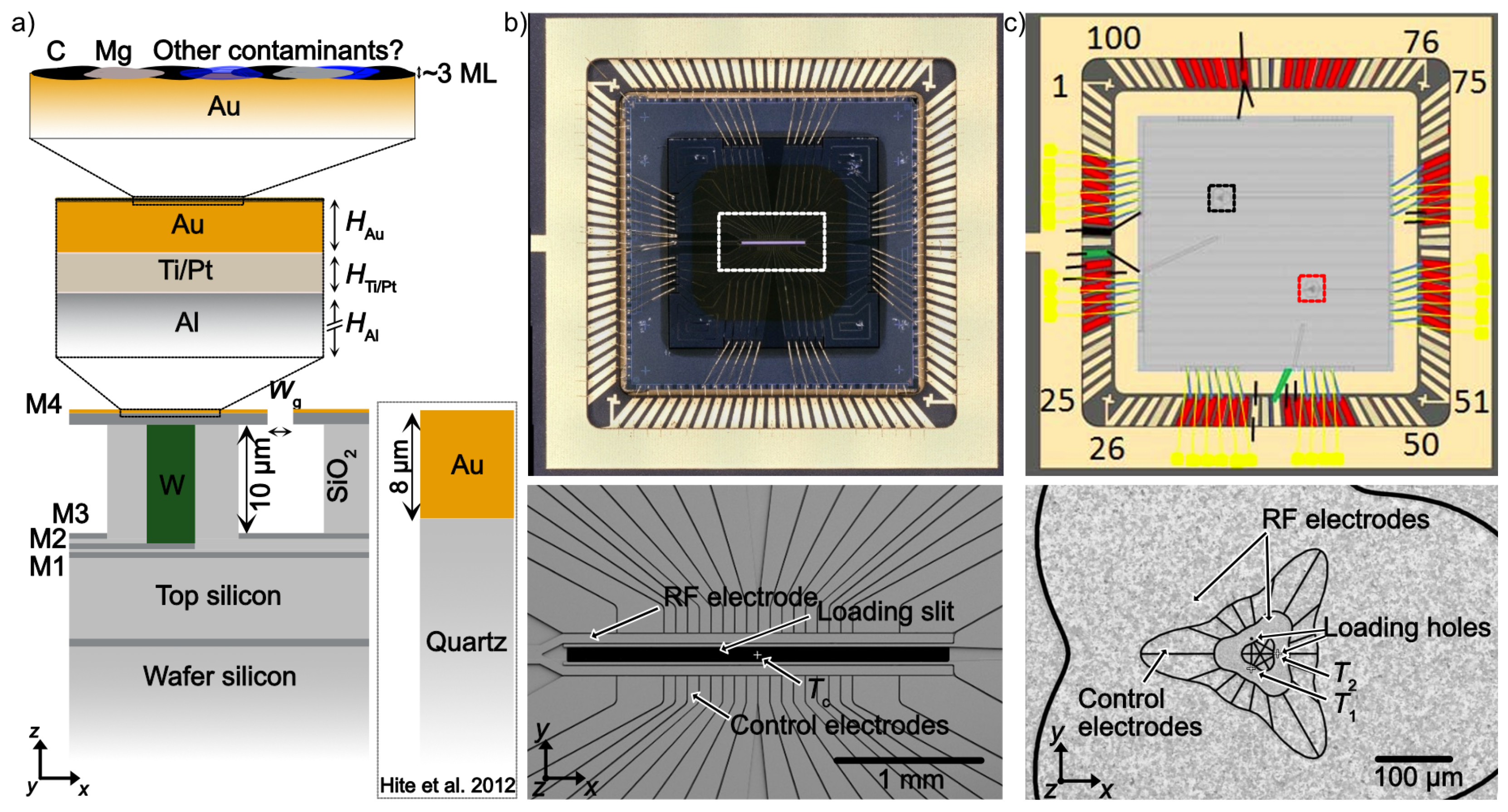

2.1. Vacuum System and Chip Architecture

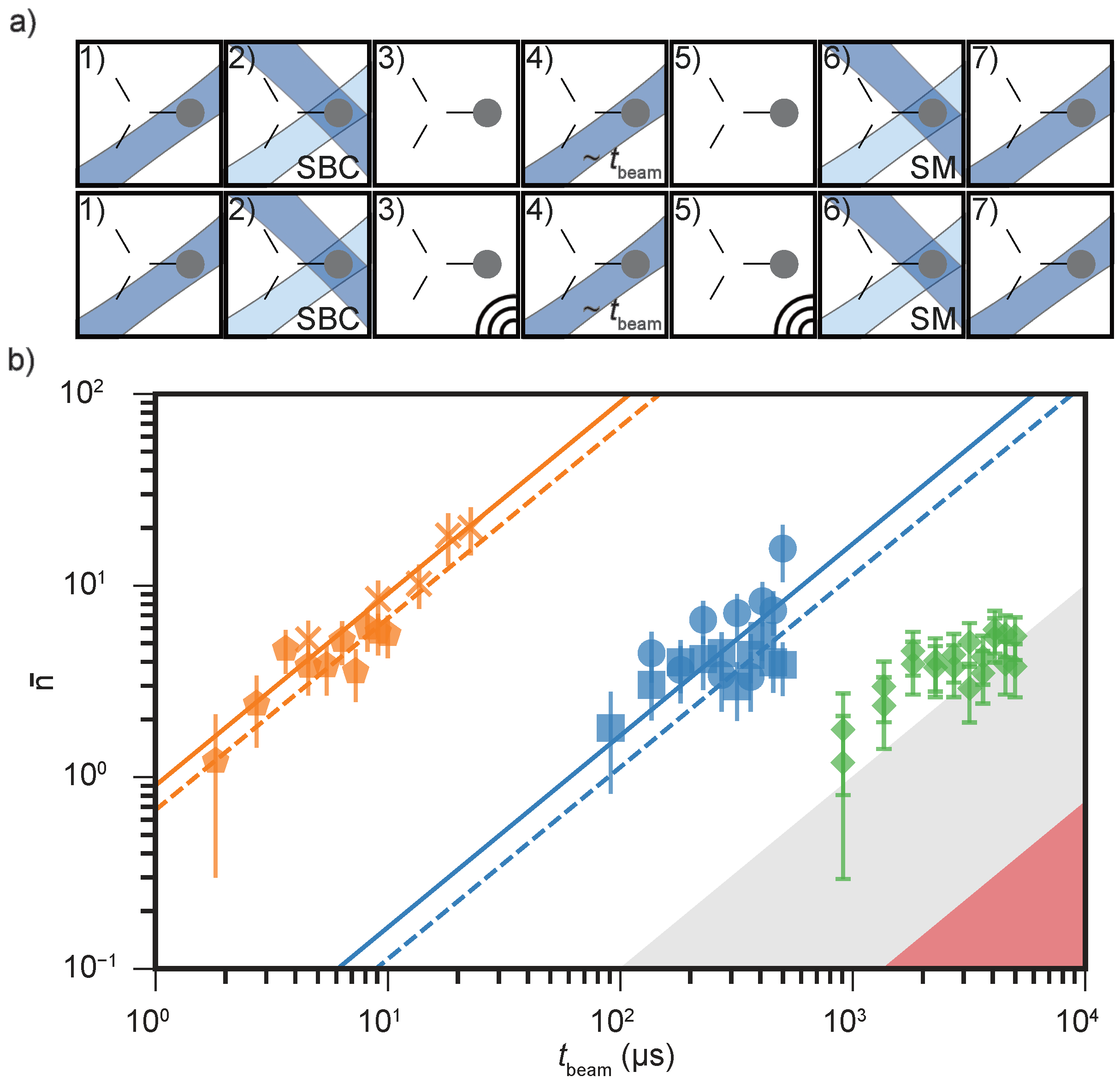

2.2. Electric-Field Sensing with Mg Ions

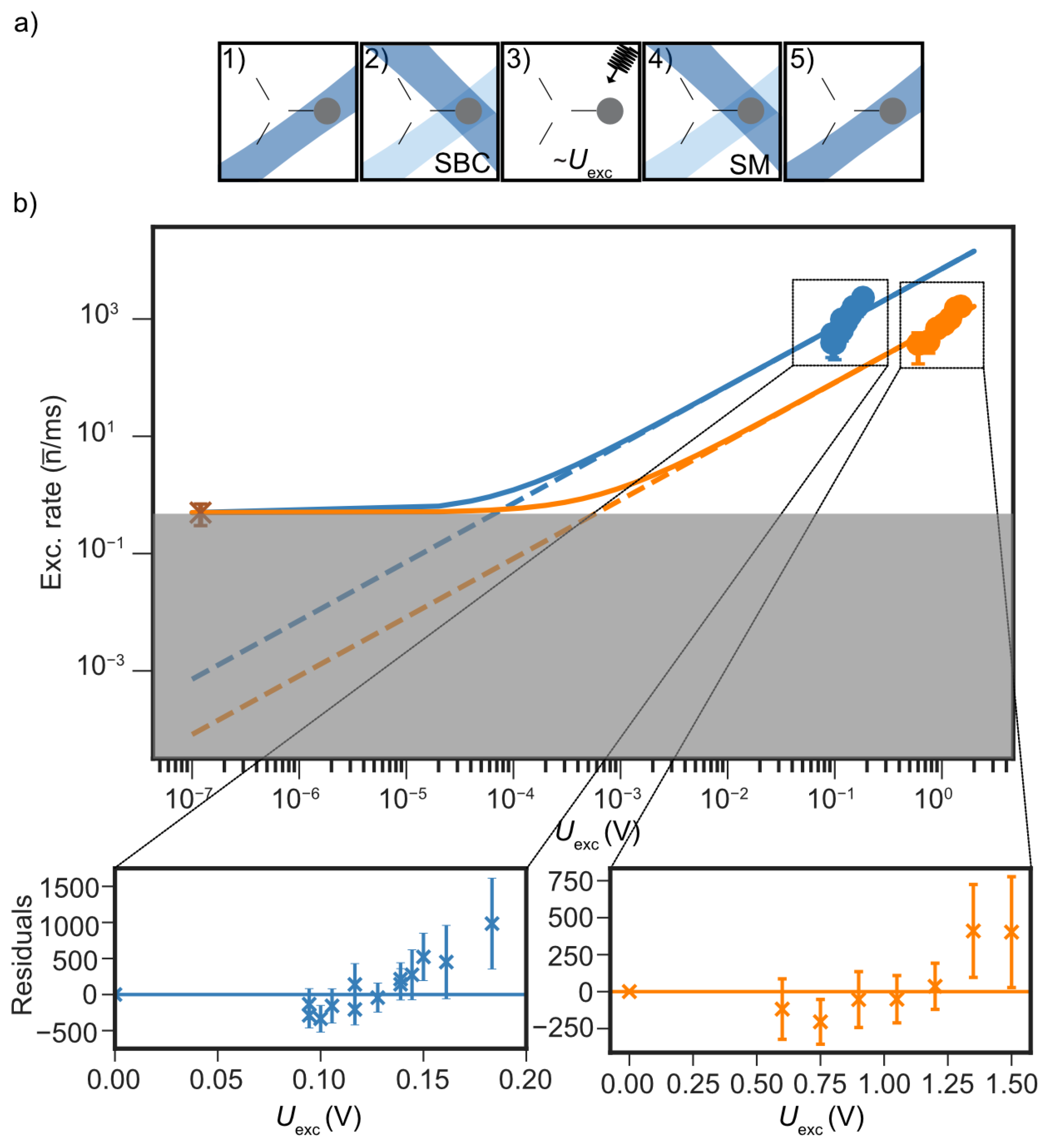

2.3. Estimates of Technical Noise Limits

2.4. Argon Ion Treatment Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Surface contamination and dielectric exposure: Prolonged exposure of the trap surface to ambient conditions before vacuum sealing can lead to adsorption of oxygen, hydrocarbons, and water, resulting in an unknown and spatially varying contamination load. Such uncontrolled variations are consistent with the large spread in electric-field noise observed across nominally identical traps [23]. Even after sputter cleaning, residual adsorbates may remain near the metal surface and alter local work functions. Slow surface migration of adsorbed species at ambient temperature could further modify the spatial distribution of dipoles over time, thereby influencing electric-field fluctuations [36,64]. Excessive sputtering may also thin the top metal stack and locally expose dielectric regions, which are known to host charge traps and contribute additional electric-field noise [65].

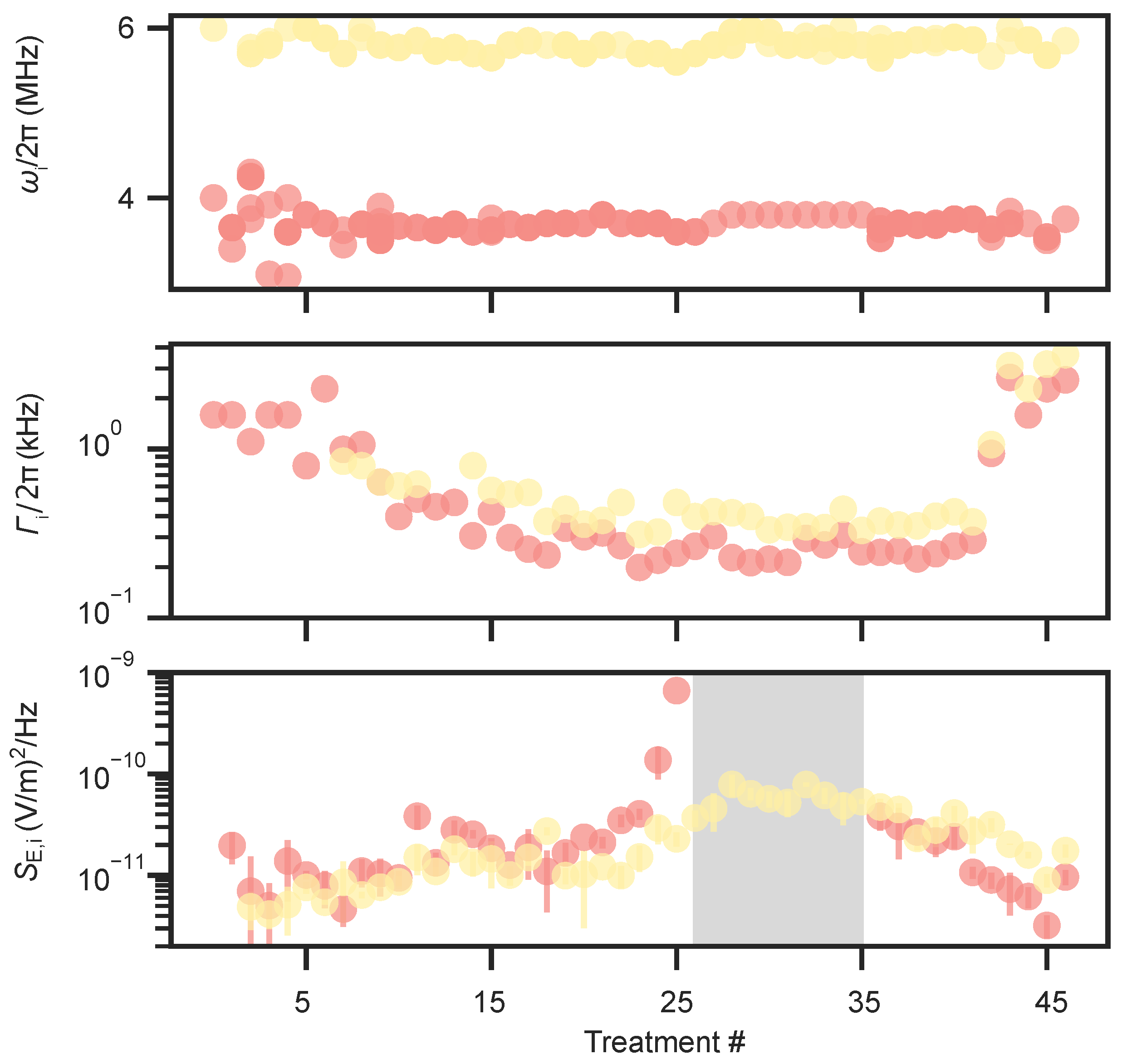

- Surface roughening and morphological modification: The changes in heating and dephasing observed here can be qualitatively interpreted within the framework of thermally activated fluctuators. One study reported a similar non-monotonic behavior following successive ion treatments and attributed it to transient surface smoothing that increased the spatial correlation among fluctuators [23]. Within this picture, the initial removal of loosely bound contaminants shifts the activation-energy distribution of fluctuators toward higher energies, suppressing slow patch-potential drifts and improving motional coherence, while the temporary smoothing enhances high-frequency noise and thus motional heating. As sputtering continues, progressive roughening could break these correlations, which broadens the fluctuator distribution, and leads to a reduction in accompanied by an increase in dephasing. In contrast, another study observed comparable non-monotonic heating behavior when only a few monolayers of contaminants remained on the surface, suggesting that residual adsorbates, rather than morphological evolution alone, may play a dominant role [60]. Additionally, under oblique ion-beam incidence, curvature-dependent sputter erosion can lead to the onset of nanoscale ripple patterns on the surface [66]. Such directional roughening may modify the local electric-field environment, potentially contributing to spatial variations in the field experienced by the trapped ions. Together, these experimental and theoretical insights [67] suggest that both surface morphology and adsorbate coverage jointly influence the spatial correlations of fluctuating surface dipoles, contributing to the complex, non-monotonic noise evolution observed in this work. It thus appears that surface cleaning, while often necessary, may not be sufficient to achieve low heating rates.

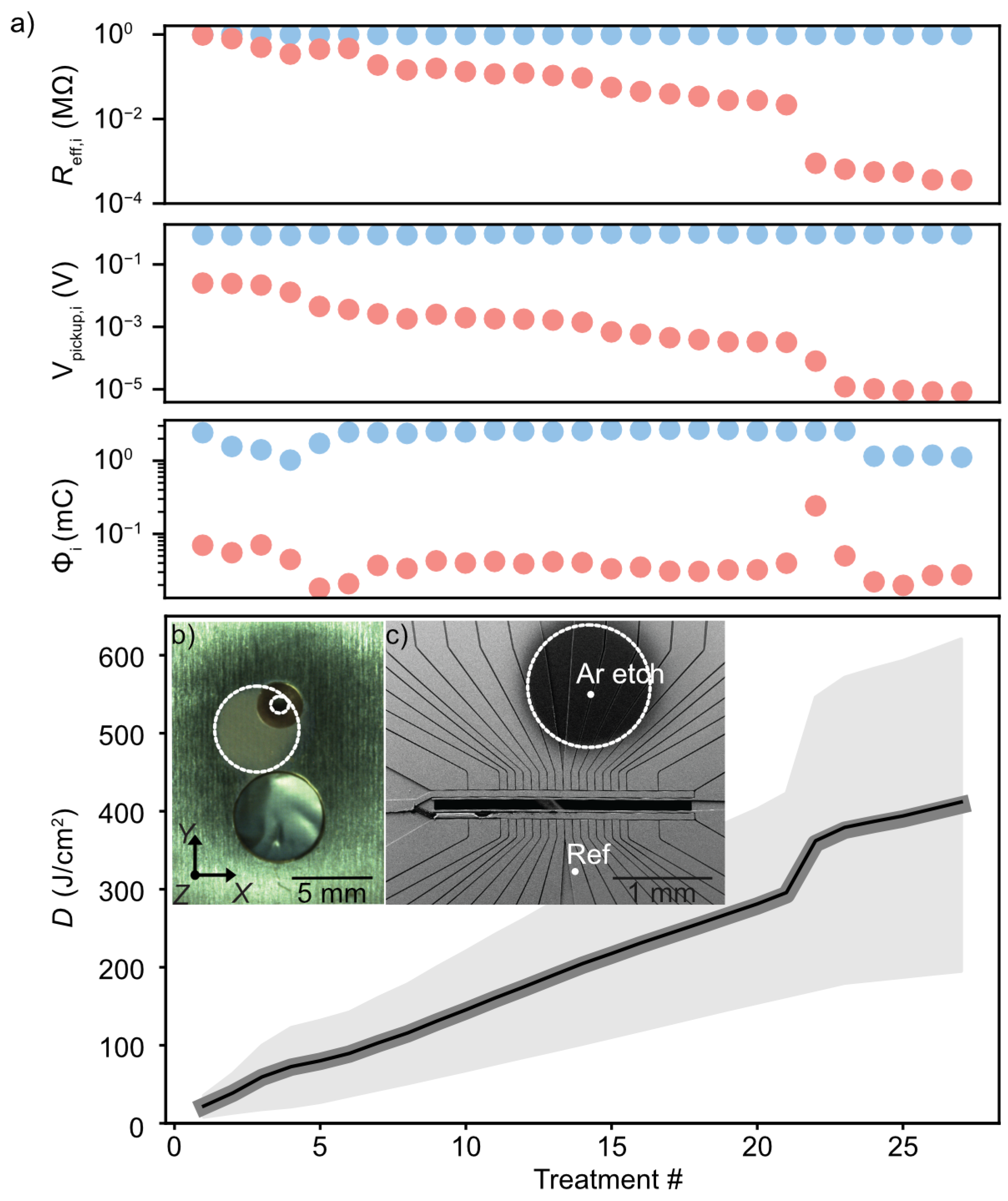

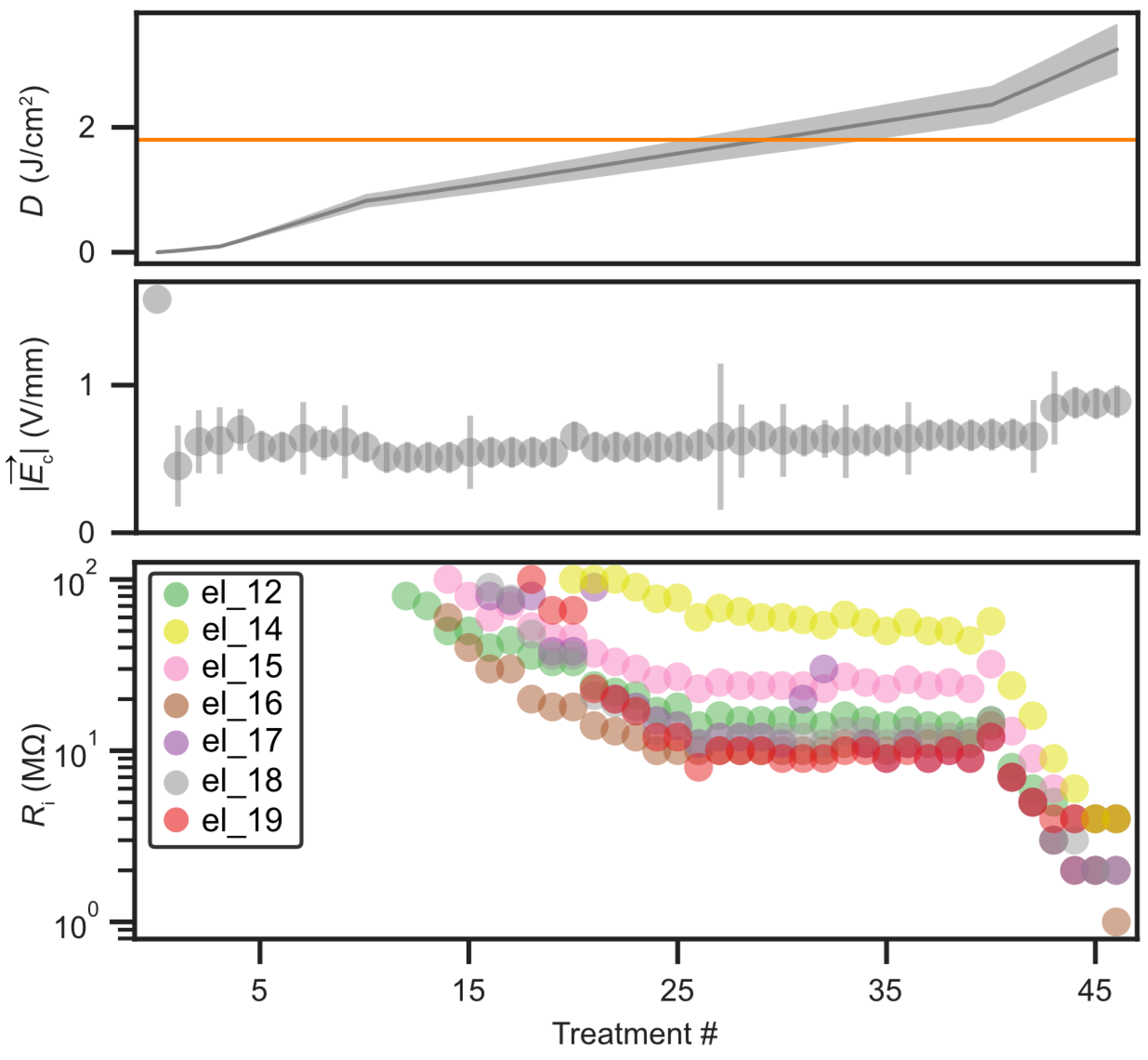

- Redeposition of sputtered material: Sputtered atoms originating from both the electrode surfaces and the nearby mask, predominantly Au from the top layer and the gold-plated mask but also Pt, Ti, Al, and trace Cu, can re-adsorb non-uniformly across the trap surface. Such multi-material redeposition alters the local work function and creates microscopic potential gradients that manifest as quasi-static patch potentials and broadband electric-field noise. In addition to larger-scale coverage variations, redeposition may also form nanoscale clusters or atomic patches of metals distinct from the underlying layer (for example, small Al or Ti aggregates on Au), which can further enhance work-function contrast and local electric-field fluctuations [16]. This process is analogous to oven loading, where unintentional deposition of atomic species on trap electrodes is known to modify stray fields and increase heating [16]. We also observe the gradual formation of electrical connections between neighboring electrodes, evidenced by a measurable decrease in their ohmic resistance from the nominally open state toward values of order 0.1–1 MΩ. These conductive bridges are consistent with metallic redeposition and may introduce additional Johnson and current shot noise, as well as time-dependent resistance fluctuations when small currents flow through these connections during operation.” The redeposition efficiency and resulting electrical coupling depend strongly on the sputtering geometry, ion-incidence angle, and masking configuration, and are particularly enhanced in in situ treatments where re-adsorption paths are not actively shielded.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BD | Blue Doppler (Doppler cooling beams) |

| BDD | Blue Doppler Detuned (Doppler cooling beams) |

| BDx | Blue Doppler (Resonant detection beam) |

| RD | Red Doppler (half of Repumping beams) |

| RP | Repumper (half of Repumping beams) |

| Raman beams | |

| TPSRT | Two-Photon Stimulated Raman Transitions |

| SM | Spin-Motion coupling |

| SBC | Sideband cooling |

| PI | Photo-Ionization beam |

| MW | Microwave |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| DC | Direct Current |

| RC | Resistor and Capacitor |

| CMOS | Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor |

| CPGA | Ceramic Pin Grid Array |

| PMT | Photon Multiplier Tube |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| EDX | Energy Dispersive X-Ray |

| UHV | Ultra-High Vacuum |

| AOM | Acousto-optic modulator |

| SRIM | The stopping and range of ions in matter |

| IR | Infra-red |

| ML | Monolayers |

| AWG | Arbitrary Waveform Generator |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

Appendix A. Investigation on Eurotrap

| Element | Au | Ti | Pt | Al | Cu | Si | O | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etched region | NA | 1.3(1) | NA | 92.7(8) | 0.3(1) | 0.5(1) | 1.5(3) | 3.7(8) |

| Reference region | 49.4(6) | 2.4(1) | 13.1(5) | 30.7(4) | NA | NA | NA | 4.3(6) |

References

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, S.; Elkouss, D.; Hanson, R. Quantum internet: A vision for the road ahead. Science 2018, 362, eaam9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leon, N.P.; Itoh, K.M.; Kim, D.; Mehta, K.K.; Northup, T.E.; Paik, H.; Palmer, B.S.; Samarth, N.; Sangtawesin, S.; Steuerman, D.W. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 2021, 372, eabb2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, I. Engineering high-coherence superconducting qubits. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.R.; Chiaverini, J.; Häffner, H. Materials challenges for trapped-ion quantum computers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfowicz, G.; Heremans, F.J.; Awschalom, D.D. Quantum guidelines for solid-state spin defects. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scappucci, G.; Kloeffel, C.; Veldhorst, M. The germanium quantum information route. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flensberg, K.; von Oppen, F.; Stern, A. Engineered platforms for topological superconductivity and Majorana zero modes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cotler, J.; Huang, H.Y.; Li, J. The complexity of NISQ. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, B.C.; Srinivas, R.; Nadlinger, D.P.; Drmota, P.; Main, D.; Araneda, G.; Ballance, C.J.; Lucas, D.M. An elementary quantum network of entangled optical atomic clocks. Nature 2022, 609, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malia, B.K.; Wu, Y.; Martínez-Rincón, J.; Kasevich, M.A. Distributed quantum sensing with mode-entangled spin-squeezed atomic states. Nature 2022, 612, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutyanskiy, V.; Canteri, M.; Meraner, M.; Bate, J.; Krcmarsky, V.; Schupp, J.; Sangouard, N.; Lanyon, B.P. Telecom-Wavelength Quantum Repeater Node Based on a Trapped-Ion Processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 213601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, S.A.; Baldwin, C.H.; Allman, M.S.; Ancona, R.; Ascarrunz, L.; Barnes, C.; Bartolotta, J.; Bjork, B.; Blanchard, P.; Bohn, M.; et al. A Race-Track Trapped-Ion Quantum Processor. Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 041052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.; Scheiner, S.; Paris, M.G.A.; Markham, D. Privacy in Networks of Quantum Sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wineland, D.J.; Monroe, C.; Itano, W.M.; Leibfried, D.; King, B.E.; Meekhof, D.M. Experimental issues in coherent quantum-state manipulation of trapped atomic ions. arXiv 1998, arXiv:quant-ph/9710025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchette, Q.A.; Kielpinski, D.; King, B.E.; Leibfried, D.; Meekhof, D.M.; Myatt, C.J.; Rowe, M.A.; Sackett, C.A.; Wood, C.S.; Itano, W.M.; et al. Heating of trapped ions from the quantum ground state. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 63418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownnutt, M.; Kumph, M.; Rabl, P.; Blatt, R. Ion-trap measurements of electric-field noise near surfaces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 1419–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, D.A.; Colombe, Y.; Wilson, A.C.; Brown, K.R.; Warring, U.; Jördens, R.; Jost, J.D.; McKay, K.S.; Pappas, D.P.; Leibfried, D.; et al. 100-Fold Reduction of Electric-Field Noise in an Ion Trap Cleaned with In Situ Argon-Ion-Beam Bombardment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, J.A.; Greene, A.; Stuart, J.; McConnell, R.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; Sage, J.M.; Chiaverini, J. Distance scaling of electric-field noise in a surface-electrode ion trap. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi-Naini, A.; Rabl, P.; Weck, P.F.; Sadeghpour, H.R. Microscopic model of electric-field-noise heating in ion traps. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 023412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, C.; Berlin-Udi, M.; Matthiesen, C.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lordi, V.; Häffner, H. Electric-field noise from thermally activated fluctuators in a surface ion trap. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 063427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinetz, L.; Hornberger, K.; Stickler, B.A. Surface-Induced Decoherence and Heating of Charged Particles. PRX Quantum 2022, 3, 030327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin-Udi, M.G. Treatments of a Surface Ion Trap: A Study of Electric-Field Noise Near a Contaminated Metal Surface. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niffenegger, R.J.; Stuart, J.; Sorace-Agaskar, C.; Kharas, D.; Bramhavar, S.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; Loh, W.; Maxson, R.T.; McConnell, R.; Reens, D.; et al. Integrated multi-wavelength control of an ion qubit. Nature 2020, 586, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, K.K.; Zhang, C.; Malinowski, M.; Nguyen, T.L.; Stadler, M.; Home, J.P. Integrated optical multi-ion quantum logic. Nature 2020, 586, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotirova, A.S.; Sun, B.; Leppard, J.D.; Wang, A.; Wang, M.; Vazquez-Brennan, A.; Nadlinger, D.P.; Moser, S.; Jesacher, A.; He, C.; et al. Low cross-talk optical addressing of trapped-ion qubits using a novel integrated photonic chip. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogle, C.W.; Dominguez, D.; Dong, M.; Leenheer, A.; McGuinness, H.J.; Ruzic, B.P.; Eichenfield, M.; Stick, D. High-fidelity trapped-ion qubit operations with scalable photonic modulators. NPJ Quantum Inf. 2023, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reens, D.; Collins, M.; Ciampi, J.; Kharas, D.; Aull, B.F.; Donlon, K.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; Felton, B.; Stuart, J.; Niffenegger, R.J.; et al. High-Fidelity Ion State Detection Using Trap-Integrated Avalanche Photodiodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, B.; Slichter, D.H.; Leibfried, D.; Mirin, R.P.; Nam, S.W.; Verma, V.B. Trap-integrated superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors with improved rf tolerance for trapped-ion qubit state readout. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospelkaus, C.; Warring, U.; Colombe, Y.; Brown, K.R.; Amini, J.M.; Leibfried, D.; Wineland, D.J. Microwave quantum logic gates for trapped ions. Nature 2011, 476, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, G.; Hahn, H.; Morgner, J.; Schulte, M.; Bautista-Salvador, A.; Werner, R.F.; Hammerer, K.; Ospelkaus, C. Robust and Resource-Efficient Microwave Near-Field Entangling 9Be+ Gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 260503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, R.; Burd, S.; Sutherland, R.; Wilson, A.; Wineland, D.; Leibfried, D.; Allcock, D.; Slichter, D. Trapped-Ion Spin-Motion Coupling with Microwaves and a Near-Motional Oscillating Magnetic Field Gradient. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 163201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, R.; Burd, S.C.; Knaack, H.M.; Sutherland, R.T.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Glancy, S.; Knill, E.; Wineland, D.J.; Leibfried, D.; Wilson, A.C.; et al. High-fidelity laser-free universal control of trapped ion qubits. Nature 2021, 597, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, D.T.C.; Others, U.; Guidoni, L.; Harty, T.P.; Ballance, C.J.; Blain, M.G.; Steane, A.M.; Lucas, D.M. Reduction of heating rate in a microfabricated ion trap by pulsed-laser cleaning. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 123023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidis, N.; Gerber, S.; Bolloten, G.; Ramm, M.; Ransford, A.; Ulin-Avila, E.; Talukdar, I.; Häffner, H. Surface noise analysis using a single-ion sensor. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 245435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Safavi-Naini, A.; Hite, D.A.; McKay, K.S.; Pappas, D.P.; Weck, P.F.; Sadeghpour, H.R. Electric-field noise from carbon-adatom diffusion on a Au(110) surface: First-principles calculations and experiments. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 033407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, R.; Bruzewicz, C.; Chiaverini, J.; Sage, J. Reduction of trapped-ion anomalous heating by in situ surface plasma cleaning. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 020302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, D. Exploring Multi-Dimensional Coupling and Information Transfer in a Trapped-Ion Array: A Quantum Network Perspective. Doctoral Thesis, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itano, W.M.; Wineland, D.J. Precision measurement of the ground-state hyperfine constant of 25Mg+. Phys. Rev. A 1981, 24, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.T.; Deng, K.; Che, H.; Yuan, W.H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.H. Precision measurement of the 25Mg+ ground-state hyperfine constant. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 052507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, D.; Hasse, F.; Kiefer, P.; Boeckling, F.; Schroeder, J.P.; Warring, U.; Schaetz, T. High-fidelity transport of trapped-ion qubits in a multilayer array. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, L050601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, E.; Baek, S.Y.; Blain, M.; Stick, D.; Gaultney, D.; Crain, S.; Noek, R.; Kim, T.; Maunz, P.; Kim, J. Single qubit manipulation in a microfabricated surface electrode ion trap. New J. Phys. 2013, 15, 093018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakelberg, F.; Kiefer, P.; Wittemer, M.; Schaetz, T.; Warring, U. Hybrid setup for stable magnetic fields enabling robust quantum control. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkeland, D.J.; Miller, J.D.; Bergquist, J.C.; Itano, W.M.; Wineland, D.J. Minimization of ion micromotion in a Paul trap. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 5025–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielenz, M.; Kalis, H.; Wittemer, M.; Hakelberg, F.; Warring, U.; Schmied, R.; Blain, M.; Maunz, P.; Moehring, D.L.; Leibfried, D.; et al. Arrays of individually controlled ions suitable for two-dimensional quantum simulations. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, ncomms11839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalis, H.; Hakelberg, F.; Wittemer, M.; Mielenz, M.; Warring, U.; Schaetz, T. Motional-mode analysis of trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 023401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakelberg, F.; Kiefer, P.; Wittemer, M.; Warring, U.; Schaetz, T. Interference in a Prototype of a Two-Dimensional Ion Trap Array Quantum Simulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, P.; Hakelberg, F.; Wittemer, M.; Bermúdez, A.; Porras, D.; Warring, U.; Schaetz, T. Floquet-Engineered Vibrational Dynamics in a Two-Dimensional Array of Trapped Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 213605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, R. Electrostatics of gapped and finite surface electrodes. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 023038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, J.A.; Stuart, J.; Loh, W.; McConnell, R.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; Sage, J.M.; Chiaverini, J. Method for determination of technical noise contributions to ion motional heating. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 214904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin-Udi, M.; Matthiesen, C.; Lloyd, P.N.T.; Alonso, A.M.; Noel, C.; Saarel, B.; Orme, C.A.; Kim, C.E.; Nelson, A.J.; Ray, K.G.; et al. Changes in electric field noise due to thermal transformation of a surface ion trap. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 035409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldin, I.A.; Kraft, A.; Wunderlich, C. Measuring Anomalous Heating in a Planar Ion Trap with Variable Ion-Surface Separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 023201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, C.L.; Reinhard, F.; Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibfried, D.; Blatt, R.; Monroe, C.; Wineland, D. Quantum dynamics of single trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 281–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekhof, D.M.; Monroe, C.; King, B.E.; Itano, W.M.; Wineland, D.J. Generation of Nonclassical Motional States of a Trapped Atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 76, 1796–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakestad, R.B.; Ospelkaus, C.; VanDevender, A.P.; Wesenberg, J.H.; Biercuk, M.J.; Leibfried, D.; Wineland, D.J. Near-ground-state transport of trapped-ion qubits through a multidimensional array. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 032314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, L.W.; Pederson, D. SPICE (Simulation Program with Integrated Circuit Emphasis); Technical Report UCB/ERL M382; EECS: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, R.; Warring, U.; Britton, J.W.; Sawyer, B.C.; Amini, J. Arbitrary waveform generator for quantum information processing with trapped ions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 033108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankin, A.M.; Clements, E.R.; Huang, Y.; Brewer, S.M.; Chen, J.S.; Chou, C.W.; Hume, D.B.; Leibrandt, D.R. Systematic uncertainty due to background-gas collisions in trapped-ion optical clocks. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 033419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hite, D.A.; McKay, K.S.; Pappas, D.P. Surface science motivated by heating of trapped ions from the quantum ground state. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunami, N.; Yamamura, Y.; Itikawa, Y.; Itoh, N.; Kazumata, Y.; Miyagawa, S.; Morita, K.; Shimizu, R.; Tawara, H. Energy dependence of the ion-induced sputtering yields of monatomic solids. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 1984, 31, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.F.; Ziegler, M.; Biersack, J. SRIM – The stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2010, 268, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrington, C.L.; McKay, K.S.; Baca, E.D.; Coleman, J.J.; Colombe, Y.; Finnegan, P.; Hite, D.A.; Hollowell, A.E.; Jördens, R.; Jost, J.D.; et al. Micro-fabricated stylus ion trap. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 085001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, J.A.; Stuart, J.; Slichter, D.H.; Bruzewicz, C.D.; McConnell, R.; Sage, J.M.; Chiaverini, J. Evidence for multiple mechanisms underlying surface electric-field noise in ion traps. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 063430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, M.; Fioretto, D.A.; Holz, P.C.; Schindler, P.; Messerer, V.; Schüppert, K.; Zou, Y.; Blatt, R.; Chiaverini, J.; Sage, J.; et al. Heating of a Trapped Ion Induced by Dielectric Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 230505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.M.; Harper, J.M.E. Theory of ripple topography induced by ion bombardment. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 1988, 6, 2390–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Low, G.H.; Chuang, I.L. Effects of electrode surface roughness on motional heating of trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 013418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.S.; Hite, D.A.; Colombe, Y.; Jördens, R.; Wilson, A.C.; Slichter, D.H.; Allcock, D.T.C.; Leibfried, D.; Wineland, D.J.; Pappas, D.P. Ion-trap electrode preparation with Ne+ bombardment. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.S.; Hite, D.A.; Kent, P.D.; Kotler, S.; Leibfried, D.; Slichter, D.H.; Wilson, A.C.; Pappas, D.P. Measurement of electric-field noise from interchangeable samples with a trapped-ion sensor. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 052610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Dyn. Range (Quanta) | Req. Cooling |

|---|---|---|

| Sideband Thermometry | 0.1–3 | Ground state |

| Carrier | 3–60 | Ground state or Doppler |

| Doppler | 100–1000 | Doppler |

| Beam | (MHz) | (Quanta/ms) | (Quanta/ms) | (Quanta/ms) | (Quanta/ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDx | 946 | 0.3 | ||||

| BD | 651 | 0.3 | ||||

| Raman |

| (kV) | (A) | (kV) | (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurotrap (material study) | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 20–45 |

| Triangular array (main investigation) | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 5–15 |

| Material | Thickness (Eurotrap) (nm) | Thickness (Triangle) (nm) | Yield at 2 kV (Atoms/Ion) | Yield at 0.5 kV (Atoms/Ion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | – | – | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Au | 73.7 | 50 | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| Ti | 30.5 | 25 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Pt | 31.3 | 25 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| Al | 2400 | 2400 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| – | – |

| Material | Etch Rate (nm/s) | Time for Full Removal |

|---|---|---|

| Au | 0.0179 | 69 min |

| Ti | 0.00563 | 90 min |

| Pt | 0.0104 | 50 min |

| Al | 0.0110 | 3645 min (60.7 h) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palani, D.; Hasse, F.; Kiefer, P.; Böckling, F.; Stick, D.L.; Hite, D.; Warring, U.; Schaetz, T. Argon Ion Treatment of Multi-Material Layered Surface-Electrode Traps for Noise Mitigation. Entropy 2025, 27, 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121208

Palani D, Hasse F, Kiefer P, Böckling F, Stick DL, Hite D, Warring U, Schaetz T. Argon Ion Treatment of Multi-Material Layered Surface-Electrode Traps for Noise Mitigation. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121208

Chicago/Turabian StylePalani, Deviprasath, Florian Hasse, Philip Kiefer, Frederick Böckling, Daniel L. Stick, Dustin Hite, Ulrich Warring, and Tobias Schaetz. 2025. "Argon Ion Treatment of Multi-Material Layered Surface-Electrode Traps for Noise Mitigation" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121208

APA StylePalani, D., Hasse, F., Kiefer, P., Böckling, F., Stick, D. L., Hite, D., Warring, U., & Schaetz, T. (2025). Argon Ion Treatment of Multi-Material Layered Surface-Electrode Traps for Noise Mitigation. Entropy, 27(12), 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121208