Unveiling Sudden Transitions Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in the Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Atoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hyperfine Interaction and Entangled States in Hydrogen

2.1. Hyperfine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom

2.2. Quantum Dynamics Under Pure Dephasing

2.3. Entangled Initial States and Dynamics

3. Trace Distance Approach to Classical and Quantum Correlations: Comparative Insights

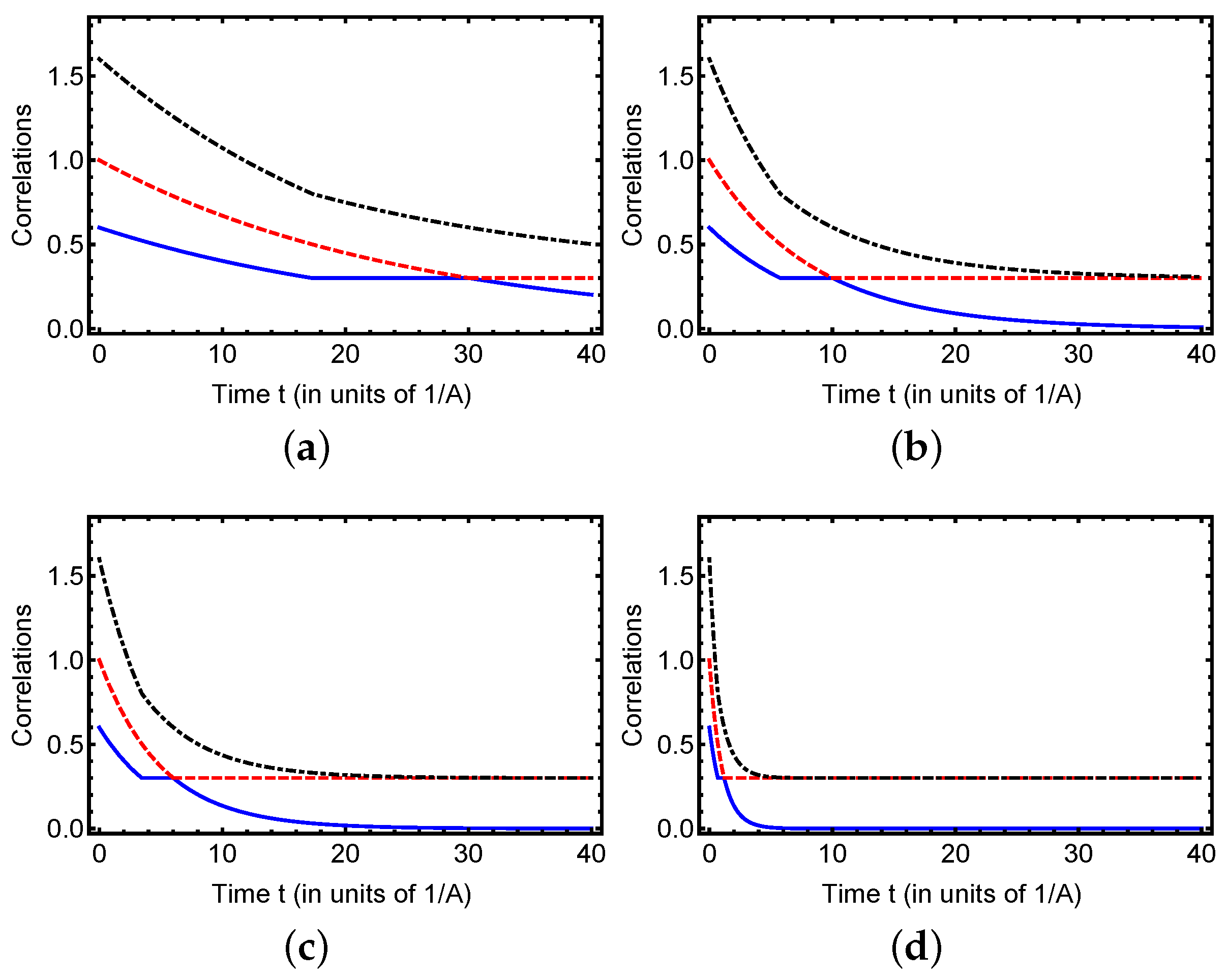

4. Numerical Analysis and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ollivier, H.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Discord: A Measure of the Quantumness of Correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 88, 017901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rulli, C.C.; Sarandy, M.S. Global Quantum Discord in Multipartite Systems. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 042109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, B.P.; Jurcevic, P.; Hempel, C.; Gessner, M.; Vedral, V.; Blatt, R.; Roos, C.F. Experimental Quantum Computing without Entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakić, N.; Lipp, Y.O.; Ma, X.; Ringbauer, M.; Kropatschek, S.; Barz, S.; Paterek, T.; Vedral, V.; Zeilinger, A.; Brukner, C.; et al. Quantum Discord as Resource for Quantum Computation. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.; Cable, H.; Williamson, M.; Vedral, V. Quantum Correlations in Mixed-State Metrology. Phys. Rev. X 2011, 1, 021022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, D.; Tufarelli, T.; Adesso, G. Quantum Discord for General Two-Qubit States: Analytical Progress. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 240402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolami, D.; Souza, A.M.; Giovannetti, V.; Tufarelli, T.; Filgueiras, J.G.; Sarthour, R.S.; Soares-Pinto, D.O.; Oliveira, I.S.; Adesso, G. Quantum Discord Determines the Interferometric Power of Quantum States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 210401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlang, T.; Trippe, C.; Ribeiro, G.A.P.; Rigolin, G. Quantum Correlations in Spin Chains at Finite Temperatures and Quantum Phase Transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 095702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streltsov, A.; Kampermann, H.; Bruss, D. Quantum Cost for State Discrimination and Classical Correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 160401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; D’Ambrosio, V.; Nagali, E.; Piani, M.; Sciarrino, F. Characterizing Quantum Correlations via Local Quantum Uncertainty. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 140501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradler, K.; Wilde, M.M.; Vinjanampathy, S.; Uskov, D.B. Lower Bounds on Quantum Discord. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 062310. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.; Chrzanowski, H.M.; Assad, S.M.; Symul, T.; Modi, K.; Ralph, T.C.; Vedral, V.; Lam, P.K. Experimental Quantum Discord in Gaussian States. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streltsov, A.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Discord and Work Extraction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 040401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Das, T.; Sadhukhan, D.; Roy, S.S.; Sen(De), A.; Sen, U. Quantum Discord and Its Allies: A Review of Recent Progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017, 81, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Rau, A.R.P.; Alber, G. Quantum Discord for Two-Qubit X States. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 042105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorda, P.; Paris, M.G.A. Gaussian Quantum Discord. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 020503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Datta, A. Quantum versus Classical Correlations in Gaussian States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, Z.-X.; Fei, S.-M. Quantum discord and geometry for a class of two-qubit states. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 022321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.; Paterek, T.; Son, W.; Vedral, V.; Williamson, M. Unified View of Quantum and Classical Correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakić, B.; Vedral, V.; Brukner, Č. Necessary and Sufficient Condition for Nonzero Quantum Discord. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 190502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomo, B.; Giorgi, G.L.; Galve, F.; Lo Franco, R.; Compagno, G.; Zambrini, R. Nonlocal Memory Effects and Quantum Correlations. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 032104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.A.; Girolami, D.; Auccaise, R.; Sarthour, R.S.; Oliveira, I.S.; Bonagamba, T.J.; de Azevedo, E.R.; Soares-Pinto, D.O.; Adesso, G. Quantum Discord in NMR Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 140501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehner, D.; Orszag, M. Geometric Quantum Discord with Bures Distance. New J. Phys. 2013, 15, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, T.R.; Cianciaruso, M.; Lo Franco, R.; Adesso, G. Solving Quantum Discord for Two-Qubit X States. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2014, 47, 405302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Piani, M.; Adesso, G. Tight Bounds for Geometric Discord. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, F.M.; Hor-Meyll, M.O.; de Oliveira, T.R.; Sarandy, M.S. Classical-Quantum States and Geometric Correlations. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 064101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlang, T.; Souza, S.; Fanchini, F.F.; da Silva, M.G.A.P. Sudden Transition in Quantum Discord Dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 024103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Feng, M. Quantum Correlation Dynamics in Two-Qubit Systems. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, A.; Aolita, L.; Cavalcanti, D.; Cucchietti, F.M.; Acín, A. Almost All Quantum States Have Nonclassical Correlations. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 052318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Eberly, J.H. Sudden Death of Entanglement. Science 2009, 323, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. Quantum Correlations in Spin Chains. Quantum Inf. Process. 2013, 12, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, B.; Lo Franco, R.; Adesso, G. Comparative Investigation of the Freezing Phenomena for Quantum Correlations under Nondissipative Decoherence. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, F.M.; da Silva, M.G.A.P.; Farias, O.J.; Souza, A.M.; de Azevedo, E.R.; Sarthour, R.S.; Saguia, A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Soares-Pinto, D.O.; Adesso, G.; et al. Nearest-Neighbor Classical Correlations Reveal Quantum Discord in Critical Spin Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 250401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montealegre, J.D.; Paula, F.M.; Saguia, A.; Sarandy, M.S. Quantum Correlations and Coherence in Spin Chains at Finite Temperatures. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 042115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Q.; Cui, X.-L.; Liang, J.-Q. Dynamical Behavior of Quantum Discord in Two-Qubit Systems with Dephasing. Ann. Phys. 2015, 354, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Luo, D.-W.; Xu, J.-B. Dynamics of Quantum Correlations under Decoherence. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 244906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S.; Chen, A.-X. Quantum Correlation Dynamics in Open Spin Systems. J. Phys. B 2014, 47, 215502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, C.; Karpat, G.; Maniscalco, S. Quantum Discord and Non-Markovian Dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 062109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, N. On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules. Philos. Mag. 1913, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H.; Salpeter, E. Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two-Electron Atoms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Series, G.W. Spectrum of Atomic Hydrogen; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics: The Basic Concepts, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheludiakov, S.; Ahokas, J.; Haar, F.; Pentikäinen, M.; Bougouffa, S. High-Precision Measurements of Spin Relaxation in Solid Hydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 225301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahokas, J.; McDonald, J.J.; Jones, R.O.; Conradi, M.S. Electron Spin Dynamics in Solid Hydrogen at Low Temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 095301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahokas, J.; McDonald, J.J.; Jones, R.O.; Conradi, M.S. Electron Spin Relaxation in Solid Hydrogen. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, N.P.; Freed, J.H.; Lee, D.M. Spin-Lattice Relaxation of Electrons in Solid Hydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.C.; Petta, J.R.; Marcus, C.M.; Hanson, M.P.; Gossard, A.C. Triplet-Singlet Spin Relaxation via Nuclei in a Double Quantum Dot. Nature 2005, 435, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petta, J.R.; Johnson, A.C.; Taylor, J.M.; Laird, E.A.; Yacoby, A.; Lukin, M.D.; Marcus, C.M.; Hanson, M.P.; Gossard, A.C. Coherent Manipulation of Coupled Electron Spins in Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Science 2005, 309, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.M.; Engel, H.A.; Dür, W.; Yacoby, A.; Marcus, C.M.; Zoller, P.; Lukin, M.D. Fault-Tolerant Architecture for Quantum Computation Using Electrically Controlled Semiconductor Spins. Nat. Phys. 2005, 1, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, T.D.; Jelezko, F.; Laflamme, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Monroe, C.; O’Brien, J.L. Quantum Computers. Nature 2010, 464, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H.; DiVincenzo, D.P. Quantum Information and Computation. Nature 2000, 404, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, L.; Gurudev Dutt, M.V.; Taylor, J.M.; Zibrov, A.S.; Jelezko, F.; Wrachtrup, J.; Hemmer, P.R.; Lukin, M.D. Coherent Dynamics of Coupled Electron and Nuclear Spin Qubits in Diamond. Science 2006, 314, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurudev Dutt, M.V.; Childress, L.; Jiang, L.; Togan, E.; Maze, J.; Jelezko, F.; Zibrov, A.S.; Hemmer, P.R.; Lukin, M.D. Quantum Register Based on Individual Electronic and Nuclear Spin Qubits in Diamond. Science 2007, 316, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Mizuochi, N.; Rempp, F.; Hemmer, P.; Watanabe, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Jacques, V.; Gaebel, T.; Jelezko, F.; Wrachtrup, J. Multipartite Entanglement Among Single Spins in Diamond. Science 2008, 320, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.D.; Dobrovitski, V.V.; Toyli, D.M.; Jelezko, F.; Awschalom, D.D. Gigahertz Dynamics of a Strongly Driven Single Quantum Spin. Science 2009, 326, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommassini, P.; Timmermans, E.; de Toledo Piza, A.F.R. Relaxation and Decoherence in Two-Level Quantum Systems. Am. J. Phys. 1998, 66, 881. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Du, K.; Li, Y. Decoherence and Classical Correlation in a Two-Level System Coupled to an Environment. Phys. A 2005, 346, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benatti, F.; Floreanini, R. Open Quantum Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Information and Computation; Lecture Notes for Physics 229; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, L.; Piilo, J.; Maniscalco, S. Sudden Transition Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 200401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.S.; Xu, X.Y.; Li, C.F.; Zhang, C.J.; Zou, X.B.; Guo, G.C. Experimental Investigation of Classical and Quantum Correlations Under Decoherence. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demtröder, W. Atoms, Molecules and Photons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethick, C.J.; Smith, H. Bose–Einstein Condensation in Dilute Gases; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, Y.; Sheludiakov, S.; Khmelenko, V.V.; Scully, M.O.; Lee, D.M.; Zheltikov, A.M. Natural and Magnetically Induced Entanglement of Hyperfine-Structure States in Atomic Hydrogen. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 052804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H.; Wiesner, S.J. Communication via One- and Two-Particle Operators on Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, D.; Pan, J.-W.; Mattle, K.; Eibl, M.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Experimental Quantum Teleportation. Nature 1997, 390, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, A.; Sørensen, J.L.; Braunstein, S.L.; Fuchs, C.A.; Kimble, H.J.; Polzik, E.S. Unconditional Quantum Teleportation. Science 1998, 282, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.L.; Xu, J.B.; Yao, D.X.; Zhang, Y.Q. Sudden Transition Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in Dissipative Cavity QED and Stationary Quantum Discord. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 022312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, G.; Rossi, M.A.; Maniscalco, S. IBM Q Experience as a Versatile Experimental Testbed for Simulating Open Quantum Systems. npj Quantum Inf. 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.W. Frozen Discord for Three Qubits in a Non-Markovian Dephasing Channel. Phys. A 2024, 646, 129884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, K.; Bougouffa, S. Quantum Coherence and Purity in Dissipative Hydrogen Atoms: Insights from the Lindblad Master Equation. Entropy 2025, 27, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrada, K.; Bougouffa, S. Harnessing Quantum Entanglement and Fidelity in Hydrogen Atoms: Unveiling Dynamics Under Dephasing Noise. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berrada, K.; Bougouffa, S. Unveiling Sudden Transitions Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in the Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Atoms. Entropy 2025, 27, 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111161

Berrada K, Bougouffa S. Unveiling Sudden Transitions Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in the Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Atoms. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111161

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerrada, Kamal, and Smail Bougouffa. 2025. "Unveiling Sudden Transitions Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in the Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Atoms" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111161

APA StyleBerrada, K., & Bougouffa, S. (2025). Unveiling Sudden Transitions Between Classical and Quantum Decoherence in the Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Atoms. Entropy, 27(11), 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111161