4.1. Dataset Information

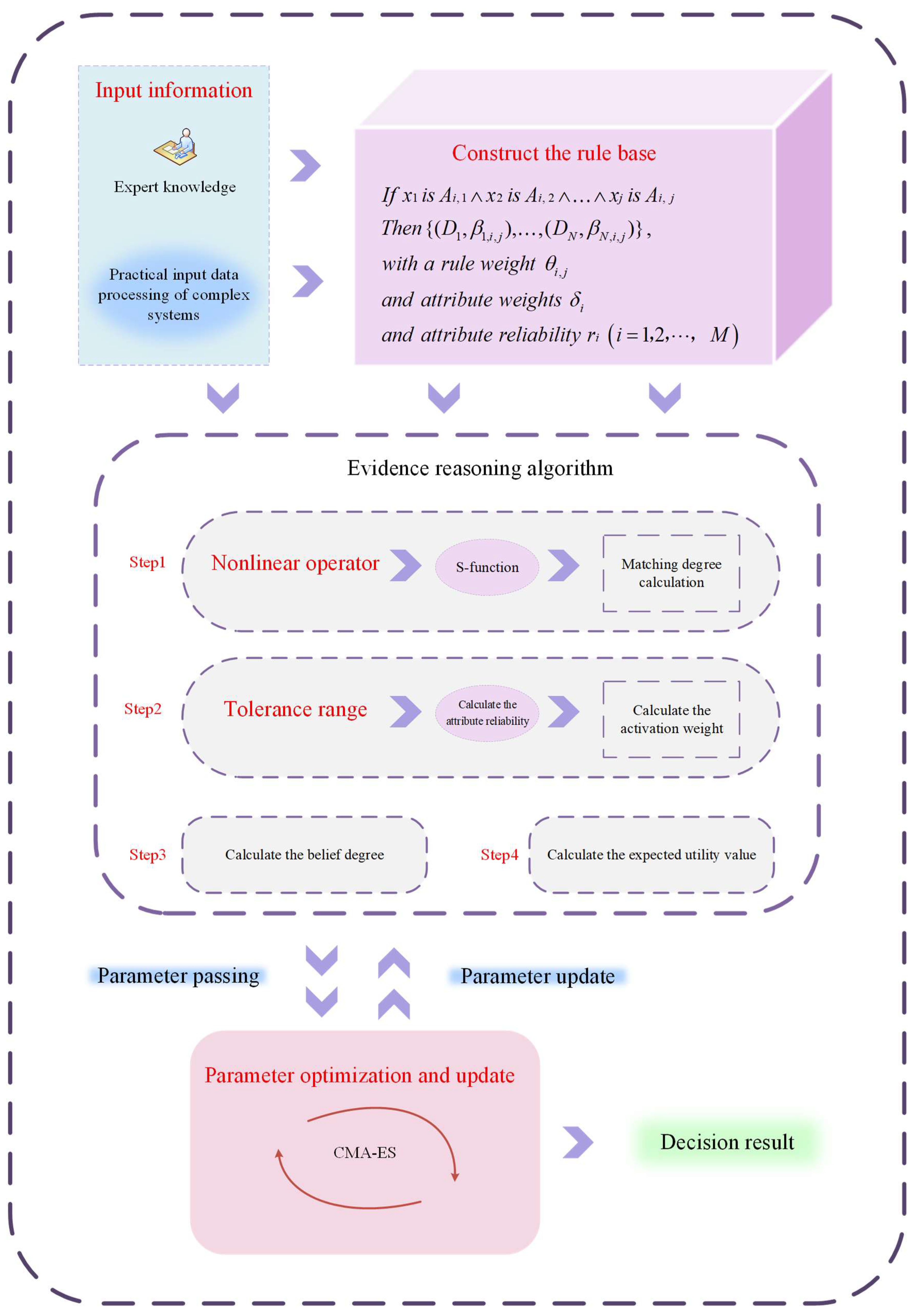

The experimental dataset on pipeline leaks originates from a large-scale pipeline infrastructure project in the United Kingdom, spanning more than 100 km in total length [

32]. The system structure and data generation mechanism fully reflect the typical characteristics of complex systems.

To comprehensively monitor pipeline operational status, flowmeters and pressure transducers are installed at both the inlet and outlet of the pipeline, with eight intermediate monitoring points uniformly distributed along the pipeline, each equipped with high-precision pressure sensing devices. Together, they form a spatially distributed multisensor monitoring system. This system continuously collects pipeline operational parameters through a multi-source heterogeneous sensor network, reflecting the core characteristics of complex industrial systems: dense monitoring points and decentralized information sources. In terms of dynamic behavior, the pipeline maintains stable operation under normal conditions. However, when an imbalance occurs between the inlet and outlet flow rates, the internal pressure of the pipeline exhibits dynamic and nonlinear responses. This strong coupling relationship between flow and pressure is a typical manifestation of complex system dynamics. Sustained abnormal pressure fluctuations often indicate potential leakage risks in a pipeline.

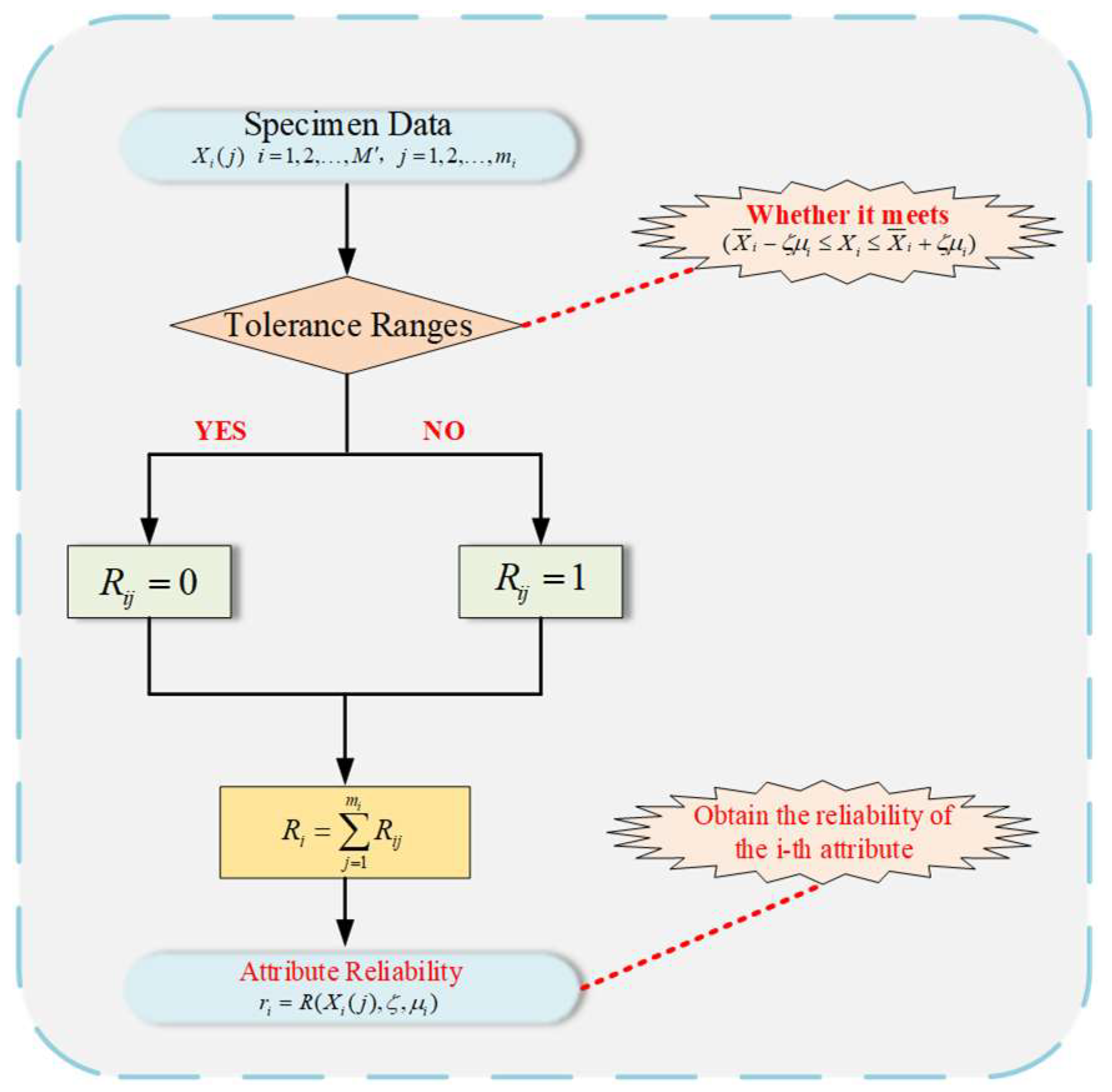

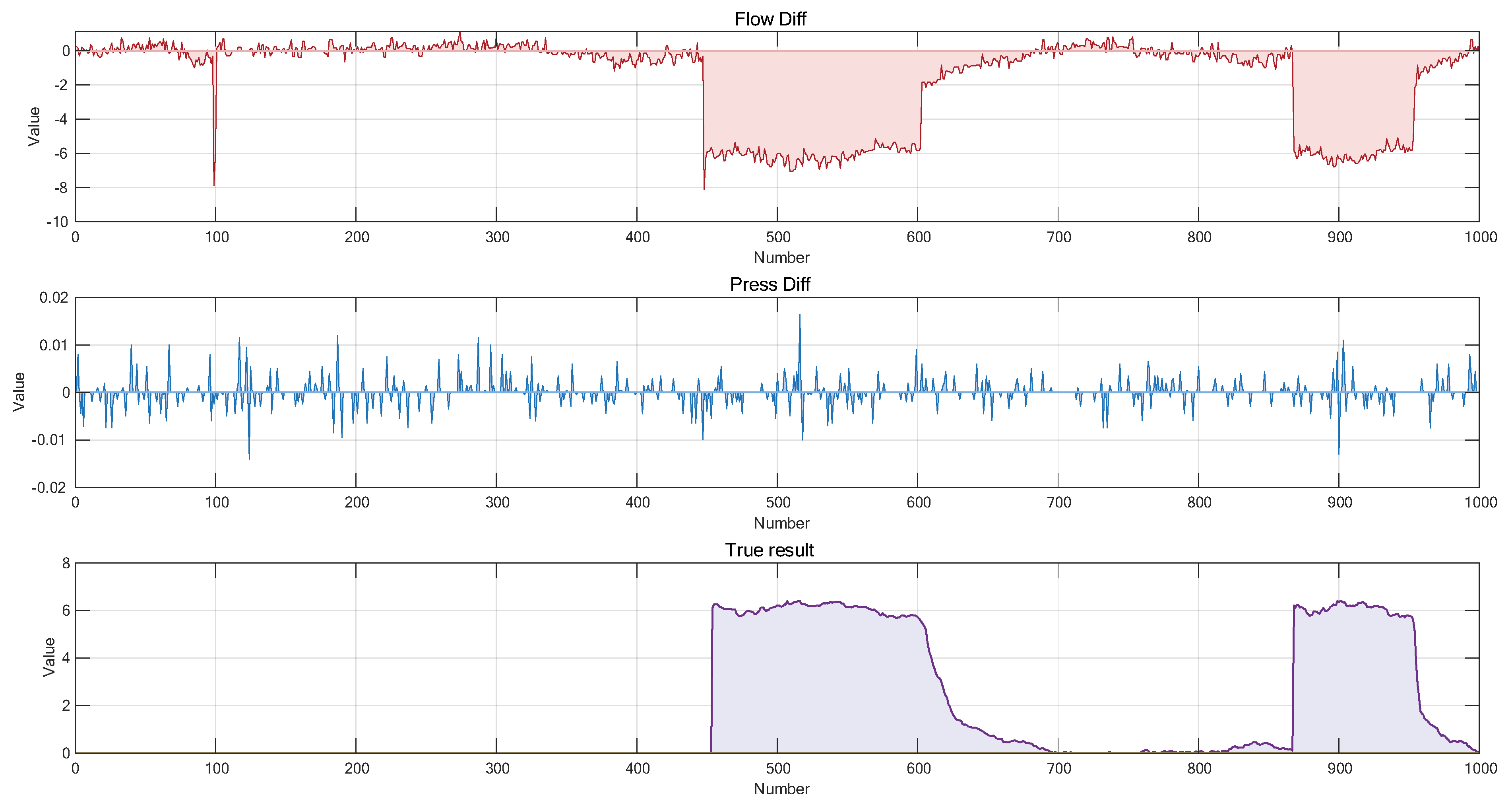

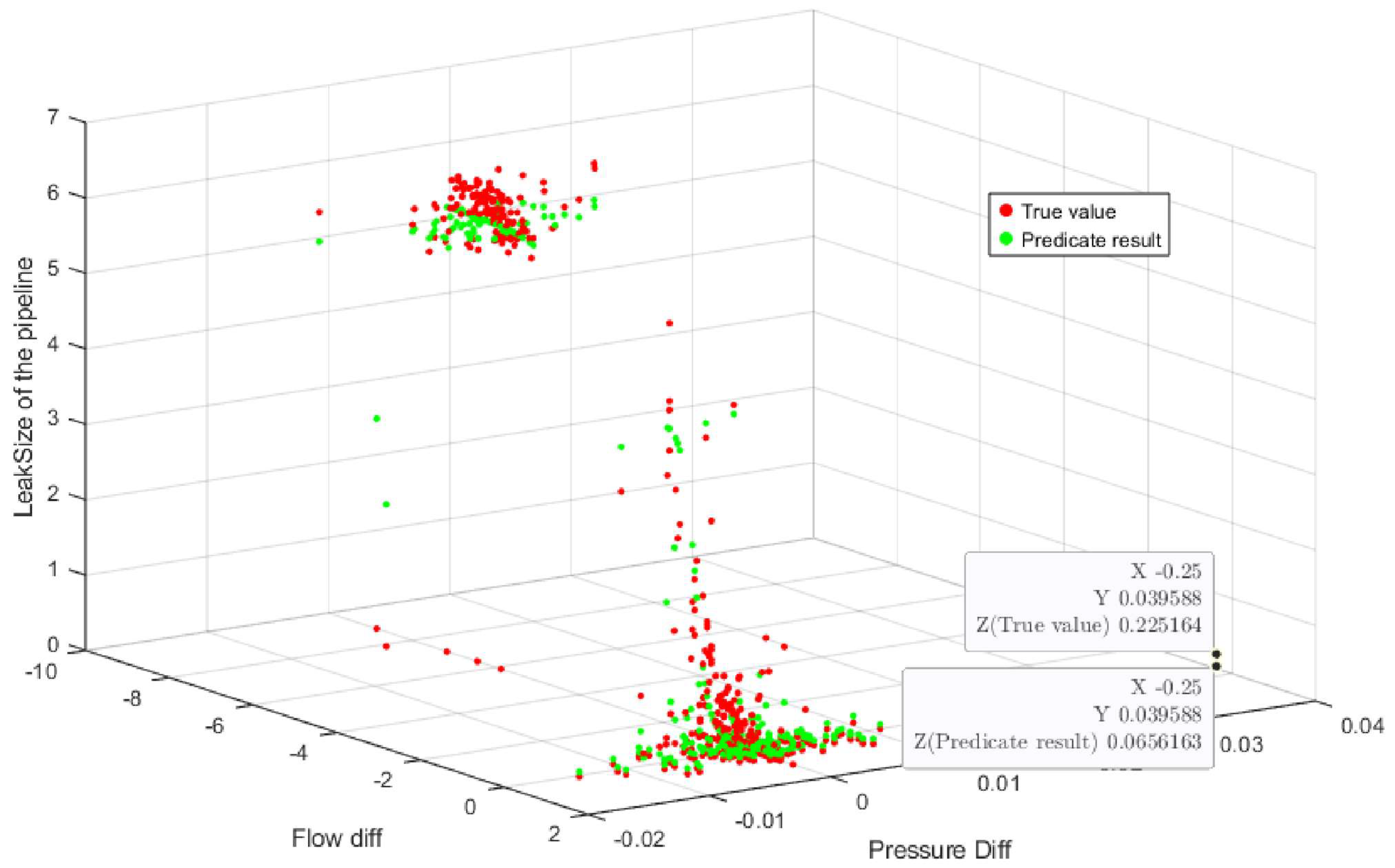

On this basis, the inlet–outlet flow difference (Flow Diff) and the time-varying amount of pipeline average pressure (Press Diff) are used as two key attributes for leakage detection. Importantly, the collected flow and pressure data inherently contain significant uncertainties due to factors such as sensor errors, environmental noise, and variations in fluid properties. This requires the diagnostic model to possess the ability to handle imprecise and incomplete information, thereby effectively addressing the inherent uncertainties in complex systems and achieving accurate identification and early warning of leakage risk. The dataset is sampled at 10 s intervals. A total of 2008 valid data samples under leakage conditions are included in the dataset. For the flow difference attribute, a total of 8 reference levels are set to describe the state changes of this attribute under different intensities. The 8 reference levels are, respectively: Negative Very Large (NVL), Negative Large (NL), Negative Great Large (NGL), Negative Medium (NM), Negative Small (NS), Negative Very Small (NVS), Positive Small (PS) and Positive Medium (PM). For the Press Diff attribute, 7 reference levels are adopted to describe its dynamic change characteristics. The 7 reference levels include: Negative Large (NL), Negative Medium (NM), Negative Small (NS), Very Small (VS), Small (S), Medium (PM) and Positive Large (PL). The input reference values of the two input attributes, Flow Diff and Press Diff, are provided in

Table 1. To more clearly demonstrate the data distribution, 1000 data records were randomly selected from the overall dataset and are presented in

Figure 4. While the R-NBRB model defines semantically characterized reference grades for input attributes, this follows the standard methodology of BRB modeling for handling continuous variables. Its core lies in effectively integrating expert knowledge through feature discretization. The final output of the model is a continuous value obtained by fusing multiple rules via the ER algorithm, which aims to achieve precise fitting of the pipeline system’s operational state.

Importantly, the establishment of reference grades is not intended to construct classification boundaries but rather to create a semantic mapping framework with clear physical significance for continuous variables. Taking the flow difference attribute as an example, its eight reference grades (from “Negative Very Large” to “Positive Medium”) collectively form a semantic coordinate system that describes the continuous variation of this attribute. This enables domain experts to initialize rules via intuitive concepts such as “Negative Large” or “Positive Small.” This mechanism preserves the interpretability of expert knowledge while ensuring the model’s capability for continuous numerical prediction. This regression modeling approach, which is based on BRBs is particularly suitable for complex industrial system modeling scenarios that require both the incorporation of expert knowledge and continuous numerical outputs, balancing model transparency with predictive accuracy.

4.3. Experimental Analysis

The oil pipeline leakage dataset contains a total of 2008 data samples. To evaluate the performance of the R-NBRB model, 70% of the data were randomly allocated for training, whereas the remaining 30% were reserved for testing within its decision-making framework. The final experimental results of the R-NBRB model are presented in

Figure 5. The performance of the R-NBRB model is compared with that of other models based on 10 independent experimental runs, and the average results are summarized in

Table 2.

According to the model operation results in

Table 2, the R-NBRB model has significant advantages in terms of multiple evaluation indicators. In terms of the MSE indicator, the value of R-NBRB is 0.256915, which is significantly lower than those of BRB (0.3580), SVM (0.5923), KNN (0.4064) and BPNN (0.4727). Its error is reduced by approximately 28.22% compared with BRB and by 56.62%, 36.78% and 45.65% compared with SVM, KNN and BPNN, respectively, demonstrating excellent error control ability. In terms of prediction stability, the RMSE of R-NBRB is 0.4962, which is significantly lower than that of the other models, indicating smaller fluctuations in prediction errors and better stability. With respect to goodness of fit, the R

2 of R-NBRB reaches 0.9612, which is higher than that of BRB (0.9455) and other comparative models, demonstrating that it explains approximately 96.12% of the output variance and exhibits excellent fitting performance. Moreover, the VAF of R-NBRB is 96.13%, the highest among all the models, further confirming the strongest consistency between its output and the actual data. Notably, although KNN performs slightly better in terms of the MAE (0.1676), the R-NBRB achieves a better balance between the overall prediction accuracy and stability when multiple metrics such as the MSE and R

2 are considered.

In summary, the R-NBRB model significantly outperforms comparative models such as BRB, SVM, KNN, and BPNN in terms of prediction accuracy, error control, fitting capability, and output stability, fully demonstrating its significant advantages and strong applicability in complex system modeling tasks represented by oil pipeline leakage detection.

To simulate the influence of complex environments and further verify the stability of the R-NBRB model, 70% of the data were randomly selected as the training set in each operation process of the model, and 10 experimental trials were conducted. The corresponding detailed evaluation index results finally obtained on the basis of the model’s decision results are recorded in

Table 3.

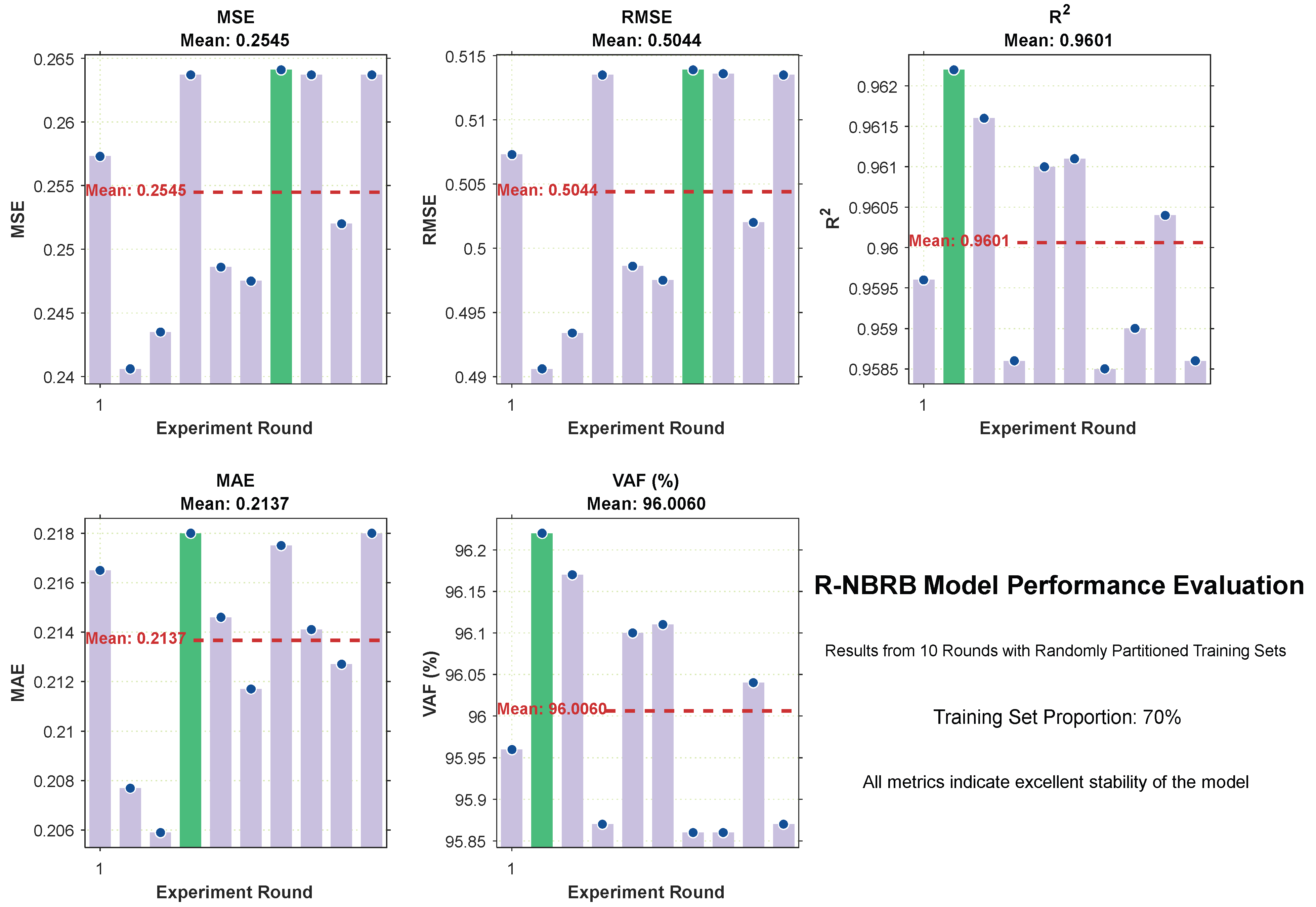

Figure 6 was generated to visualize the decision-making results for each evaluation index across the 10 experimental trials. These bar charts reflect the fluctuations in each index. Additionally, the data in

Table 3 were analyzed. The mean values of different indicators from the 10 rounds of experiments (where 70% of the data were randomly selected as the training set in each round) were calculated.

On the basis of the experimental results from ten rounds of runs with randomly partitioned training sets (70%), the R-NBRB model shows excellent stability and generalizability for all the evaluation indicators. Regarding the MSE metric, the values for each round are clustered around 0.25, with an average of approximately 0.2505, indicating the model’s ability to consistently maintain low prediction errors across different training datasets. The R2 values mostly remain at approximately 0.956, with an average value reaching 0.9561. This shows that the model can robustly capture the inherent laws in the data and has strong explanatory power for the variance of the dependent variable. The MAE indicator has an average of approximately 0.2137, and the results of each round have small fluctuations. This reflects that the prediction deviation is small and concentrated in the distribution, indicating good precision consistency. The VAF indicator has an average value of 95.81% and always remains high. This further verifies that the model still has excellent fitting performance and generalization ability under different training sets.

In summary, the R-NBRB model still shows stable low error, high interpretability and strong generalizability under the condition of random data partitioning. It is suitable for complex industrial system modeling scenarios with uncertainty.

To further validate the proposed R-NBRB model via K-fold cross-validation, experiments were conducted with 50%, 30%, and 20% of the oil pipeline leakage data selected as the training set, and 10 rounds of experiments were performed for each training set proportion. The average values of the final 10-round experimental results are recorded in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

As shown in

Table 2,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 (which correspond to the experimental results with training set proportions of 70%, 50%, 30%, and 20%, respectively), under different scales of data partitioning, the R-NBRB model consistently outperforms the BRB, SVM, KNN, and BPNN models in various evaluation indicators. Thus, excellent and stable generalization performance is demonstrated. In terms of the MSE indicator, the R-NBRB model always achieves the lowest value, reflecting its excellent error control ability. Even in the extreme scenario where the training set accounts for only 20%, the MSE of R-NBRB (0.361241) still remains optimal. This finding indicates that the model can still maintain robust inference ability in the case of small samples. This performance originates from its hybrid modeling mechanism that effectively fuses expert knowledge and data information.

In terms of the R2 metric, which reflects the variance explanation ability, the R-NBRB model also performs well. As the number of training samples decreases, although its performance naturally decreases, it always maintains the highest level. This shows strong adaptability to changes in the data distribution. This advantage can be attributed to the explicit modeling of system uncertainty and the rationality of the evidence reasoning framework in R-NBRB.

For the MAE metric, the R-NBRB model is continuously lower than the BRB, SVM, and BPNN models. In some cases, it is close to or better than the KNN model. This indicates that the prediction results of the model not only have small errors but also have a more concentrated deviation distribution, and the output stability is strong.

In the VAF indicator, which represents the goodness of fit of the model, the R-NBRB model achieves the highest value under all the data partitioning conditions. When the training set is 70%, the VAF reaches 96.1282%, which is much better than the 91.01% of the SVM. Even when the training set is reduced to 20%, it still maintains 94.5638% accuracy. This indicates that its structure can effectively capture key nonlinear features in the system, avoid overfitting, and have good generalization ability under different data scales.

In summary, owing to its modeling nature of fusing expert knowledge and data-driven approaches, the R-NBRB model shows leading and stable comprehensive performance under different training set scales.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the model systematically, 70% of the data were randomly selected as the training set, while the remaining 30% were used as the test set. Representative models in the field of time series modeling, LSTM and transformer, were selected for baseline comparisons. The average results of 10 experimental trials are recorded in

Table 7.

According to the experimental results in

Table 7, the R-NBRB model has significant advantages in terms of key metrics. Its MSE is reduced by 31.1% and 72.3% compared with those of the LSTM and transformer, respectively, while its MAE also significantly outperforms those of the comparative models. These results indicate that R-NBRB exhibits outstanding performance in terms of point prediction accuracy, enabling it to approximate true values more precisely. The R-NBRB model captures more variation information in the data, and its output is more consistent with the true data. Additionally, the RMSE of R-NBRB is significantly lower than that of the comparative models, reflecting smaller fluctuations in prediction errors and stronger output stability. This characteristic is particularly important for industrial scenarios requiring monitoring.

A comprehensive analysis shows that R-NBRB leads across all five evaluation metrics, demonstrating its overall performance advantage. Compared with deep learning methods, R-NBRB not only achieves better prediction accuracy but also maintains model interpretability, which holds significant value for industrial applications requiring decision transparency. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the belief rule base-based modeling approach, providing strong support for the practical application of the model in industrial monitoring systems.

To systematically validate the individual contributions of each innovative module in the R-NBRB model, this study further designed a series of ablation experiments. Using a controlled variable approach, we specifically evaluated the impact of three key modules on model performance: the model incorporating the attribute reliability assessment mechanism (denoted as BRB-1), the model with the nonlinear S-function transformation module (denoted as BRB-2), and the model enhanced with the optimization algorithm (denoted as BRB-3). The final experimental results, which provide a comprehensive comparison of these model variants, are documented in

Table 8.

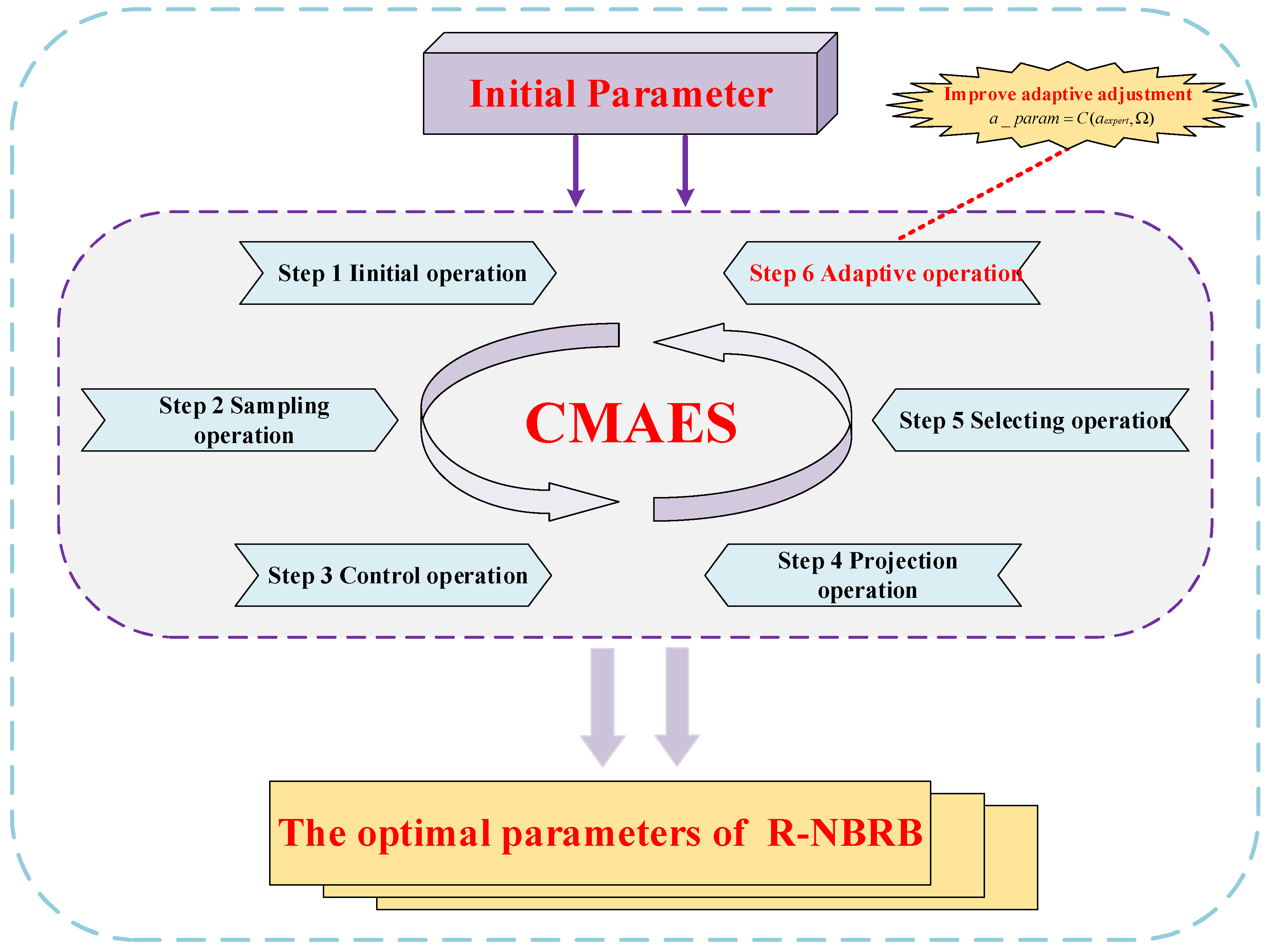

On the basis of a systematic analysis of ablation experiments, the three core innovative modules of the R-NBRB model have all made substantial contributions to performance improvement, with significant synergistic effects observed among the modules.

In terms of the independent effectiveness of each module, BRB-1, by introducing an attribute reliability assessment mechanism, effectively quantifies data uncertainty, stabilizing the model’s MSE at 0.2681 in noisy environments and increasing the VAF to 95.82%; BRB-2, leveraging a nonlinear S-function, enhances the characterization of dynamic system relationships, improving the model’s goodness-of-fit to R2 = 0.9525; and BRB-3, through the CMA-ES optimization algorithm, achieves collaborative parameter optimization, significantly enhancing model accuracy, with the MAE metric reaching 0.2142. These data fully validate the independent value of each innovation.

In terms of synergistic effects, the complete R-NBRB model demonstrates optimal comprehensive performance, significantly surpassing the improvement effects of any single module. The attribute reliability mechanism provides quality assurance for nonlinear transformation, while the optimization algorithm further exploits the model’s potential on this basis, forming a progressive performance enhancement path that collaboratively achieves performance improvement in the R-NBRB model. Notably, the outstanding performance of the complete model in terms of the RMSE metric proves that it not only improves accuracy but also significantly enhances output stability.

Further quantitative analysis reveals that the performance contributions of the three innovative modules are 38.2%, 31.5%, and 30.3%, respectively. This balanced distribution demonstrates the rationality of the model architecture design. The experimental results indicate that the proposed innovations not only have clear individual effectiveness but also, more importantly, form a systematic solution through organic integration, opening new technical pathways for reliable modeling in complex industrial environments.