Quantum Shannon Information Theory—Design of Communication, Ciphers, and Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

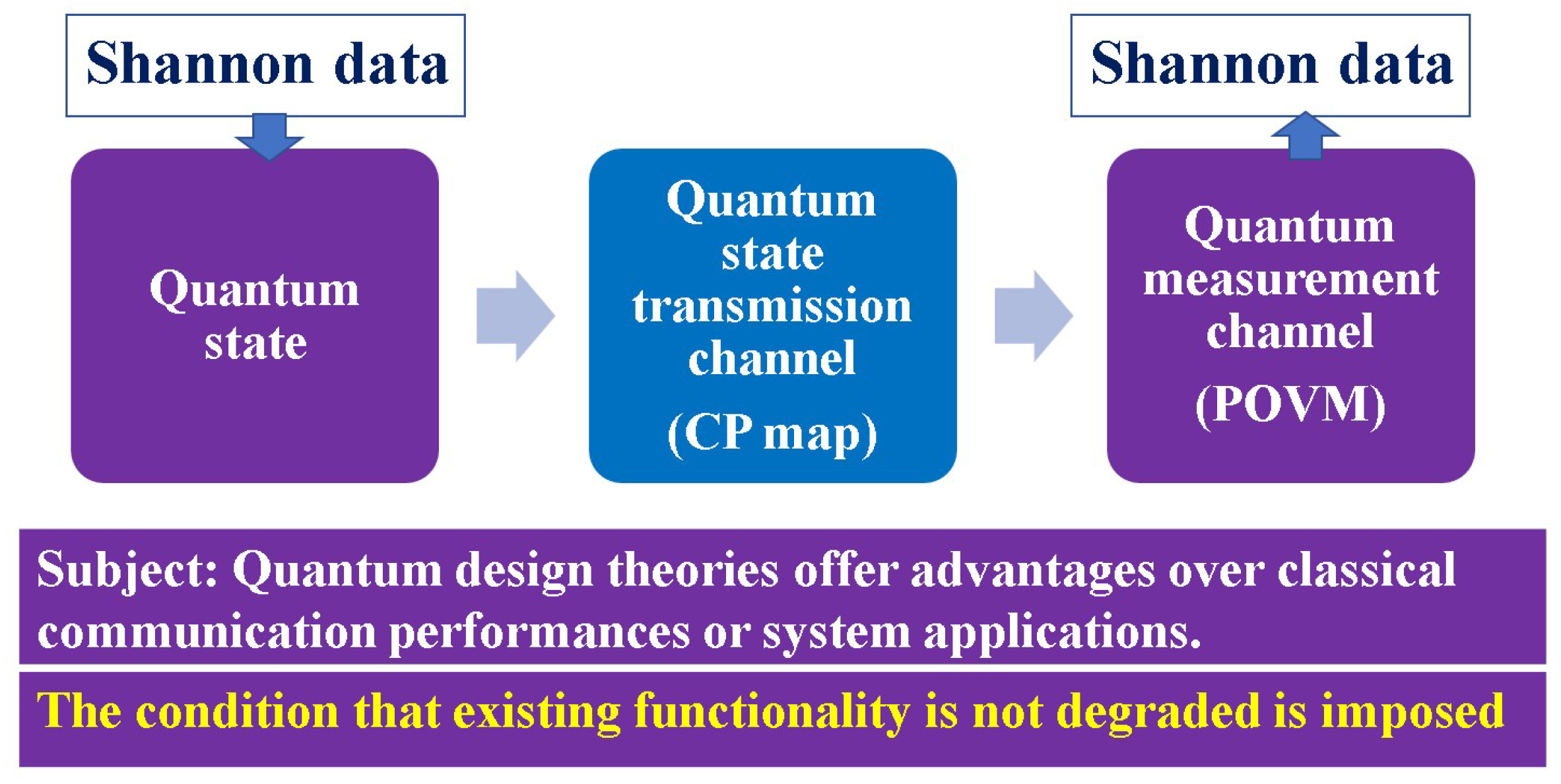

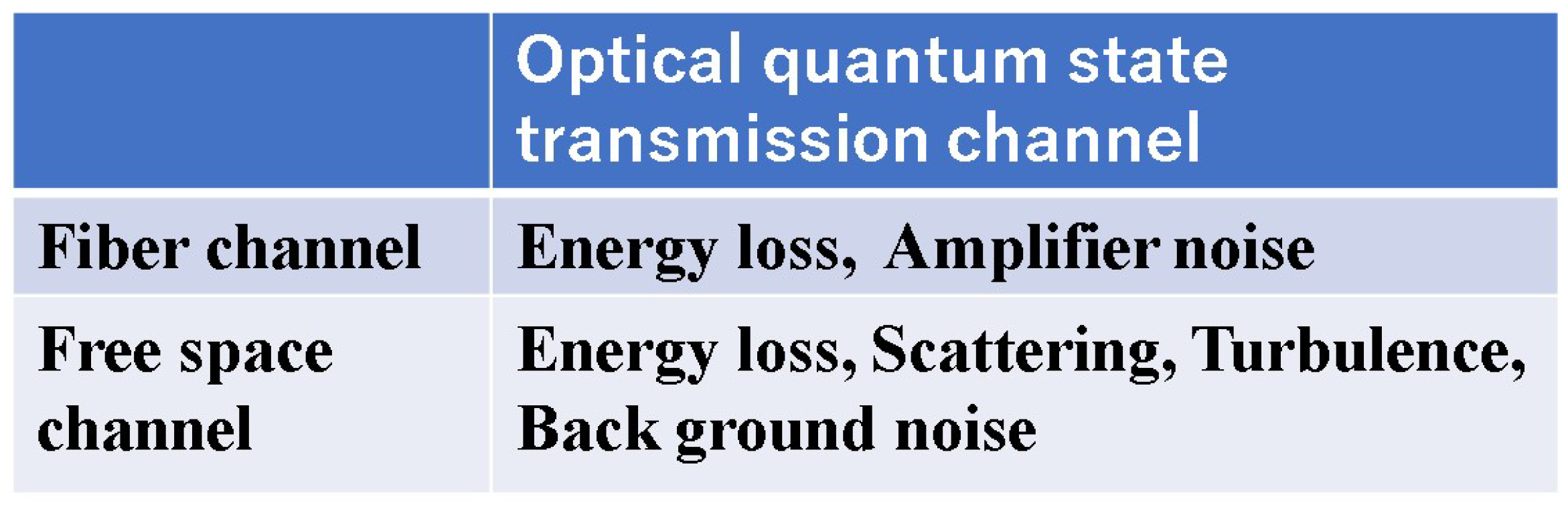

2. General Quantum Communication Channel Model

3. Mathematical Foundation of Generalized Quantum Measurement and Decision Operator

3.1. Mathematical Formulae of Generalized Quantum Measurement

3.2. Quantum Decision Operator

3.3. Decision Operator Based on Entangled Measurement (or Collective Measurement)

4. Structure of Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory

4.1. Quantum Detection Theory

4.1.1. Basic Formula

4.1.2. Useful Analytical Issues

4.1.3. Decision Operator Based on SRM of Entangled Measurement

4.1.4. Quantum Advantage in Detection

4.2. Quantum Estimation Theory

4.2.1. Formulation

4.2.2. Example for Coherent-State Signal

4.2.3. Application of Lie Algebra for Non-Commutative Parameters

- Step 1: Derive the estimation operators for simultaneous estimation of non-commutative quantities based on the symmetric logarithmic differential operator formulae in Equations (32) and (33).

- Step 2: Construct a decision operator that expresses simultaneous measurement of non-commuting quantities based on the minimum uncertain state for the two operators obtained.

4.2.4. Importance of Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Estimation

5. Quantum Shannon Information Transmission Theory

5.1. Channel Capacity

5.1.1. Finite, Discrete Alphabet System

5.1.2. Infinite Alphabet System (Continuous)

5.1.3. Quantum Advantage in Capacity

5.1.4. Implementation Problem

5.2. Quantum Reliability Function and Quantum Cut-Off Rate

5.2.1. Reliability Function

5.2.2. Quantum Cut-Off Rate

6. Examples of Reliability Function and Cut-Off Rate

6.1. Finite, Discrete Alphabet System

6.1.1. Analytical Method

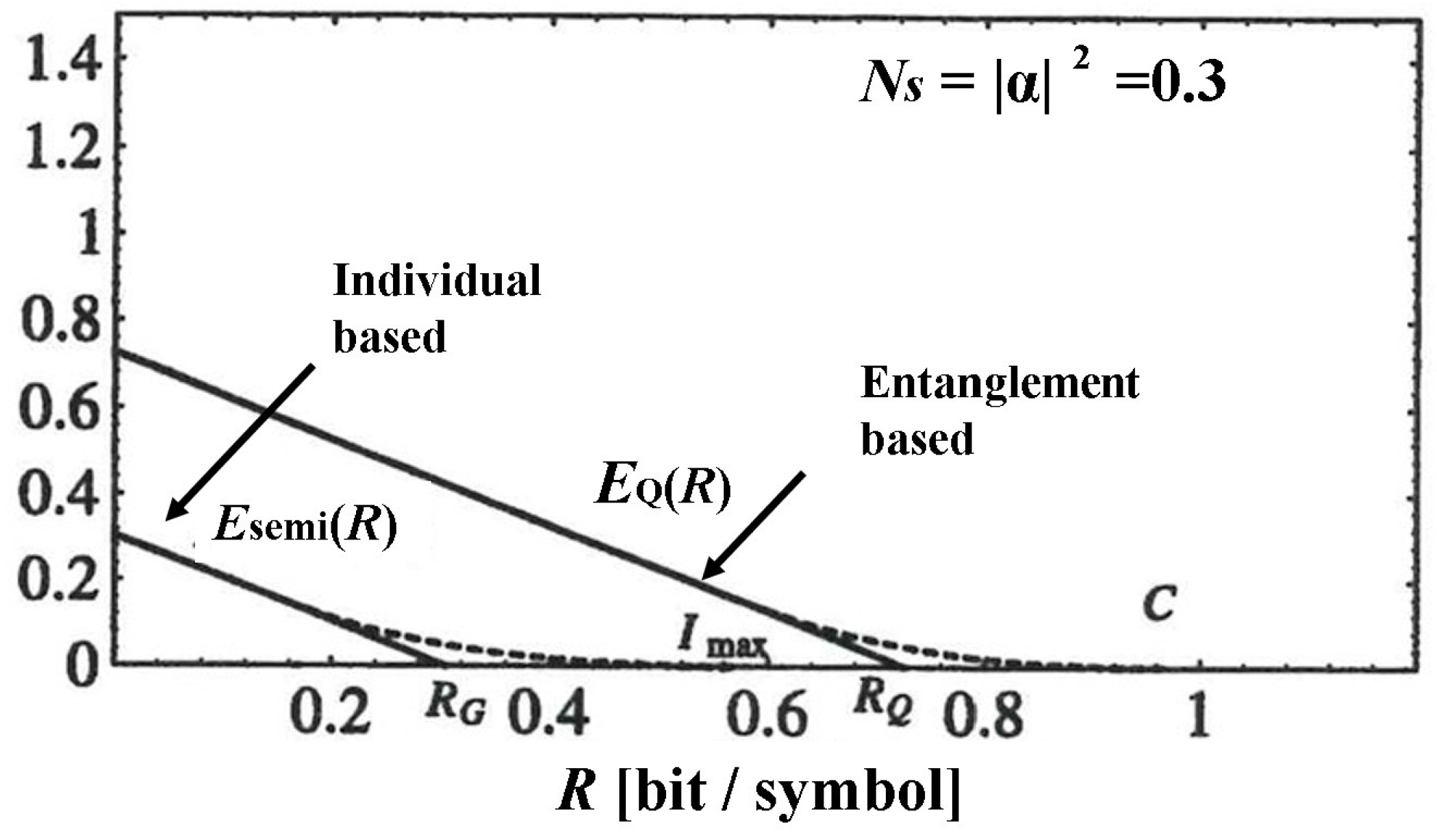

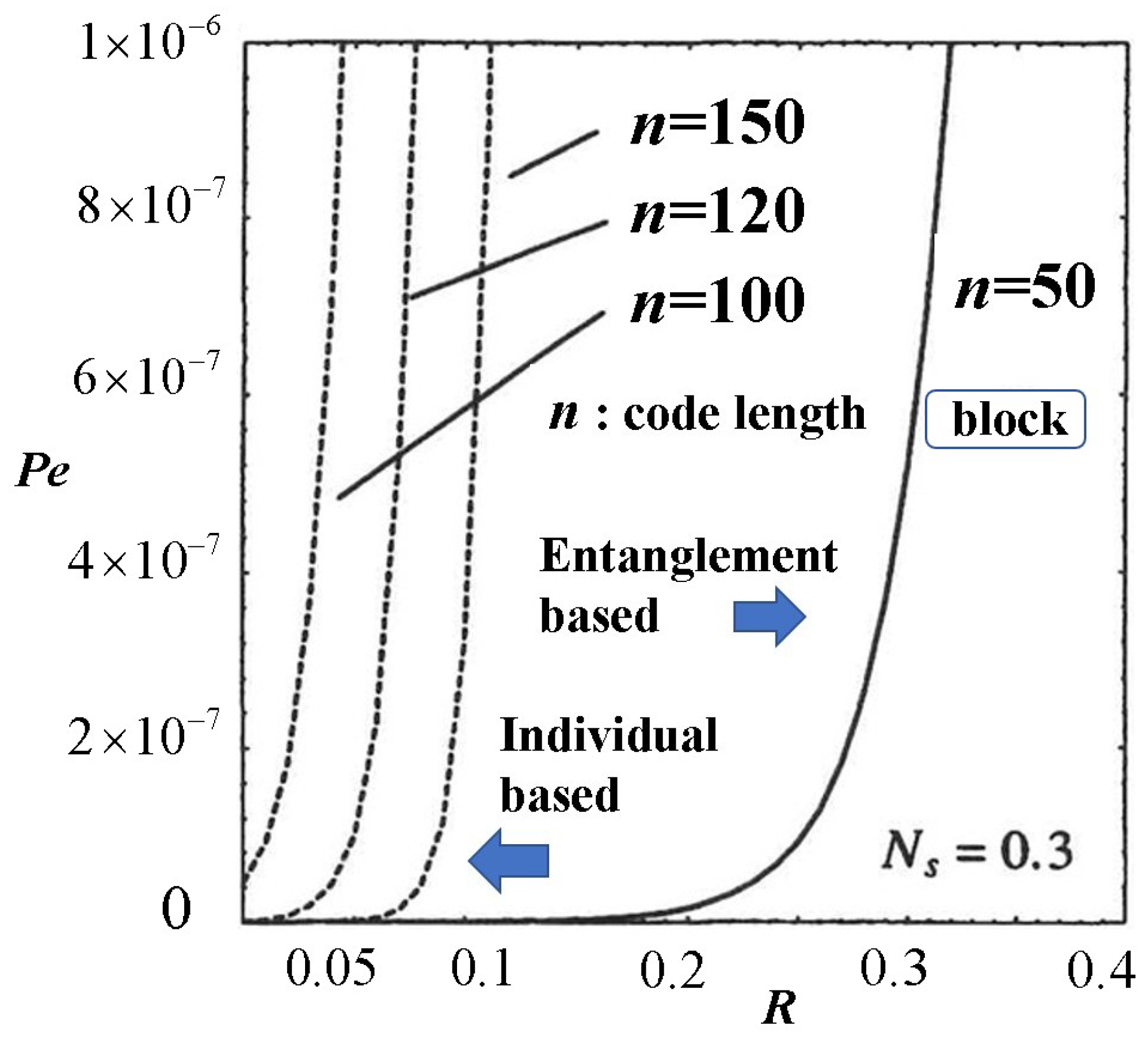

6.1.2. Quantum Advantage of Decision Operator Based on Entangled Measurement

6.2. Infinite Alphabet System (Continuous)

6.2.1. Reliability Function

6.2.2. Cut-Off Rate

6.2.3. Example of Cut-Off Rate for Gaussian Channel

6.3. Importance of Cut-Off Rate and Quantum Advantage

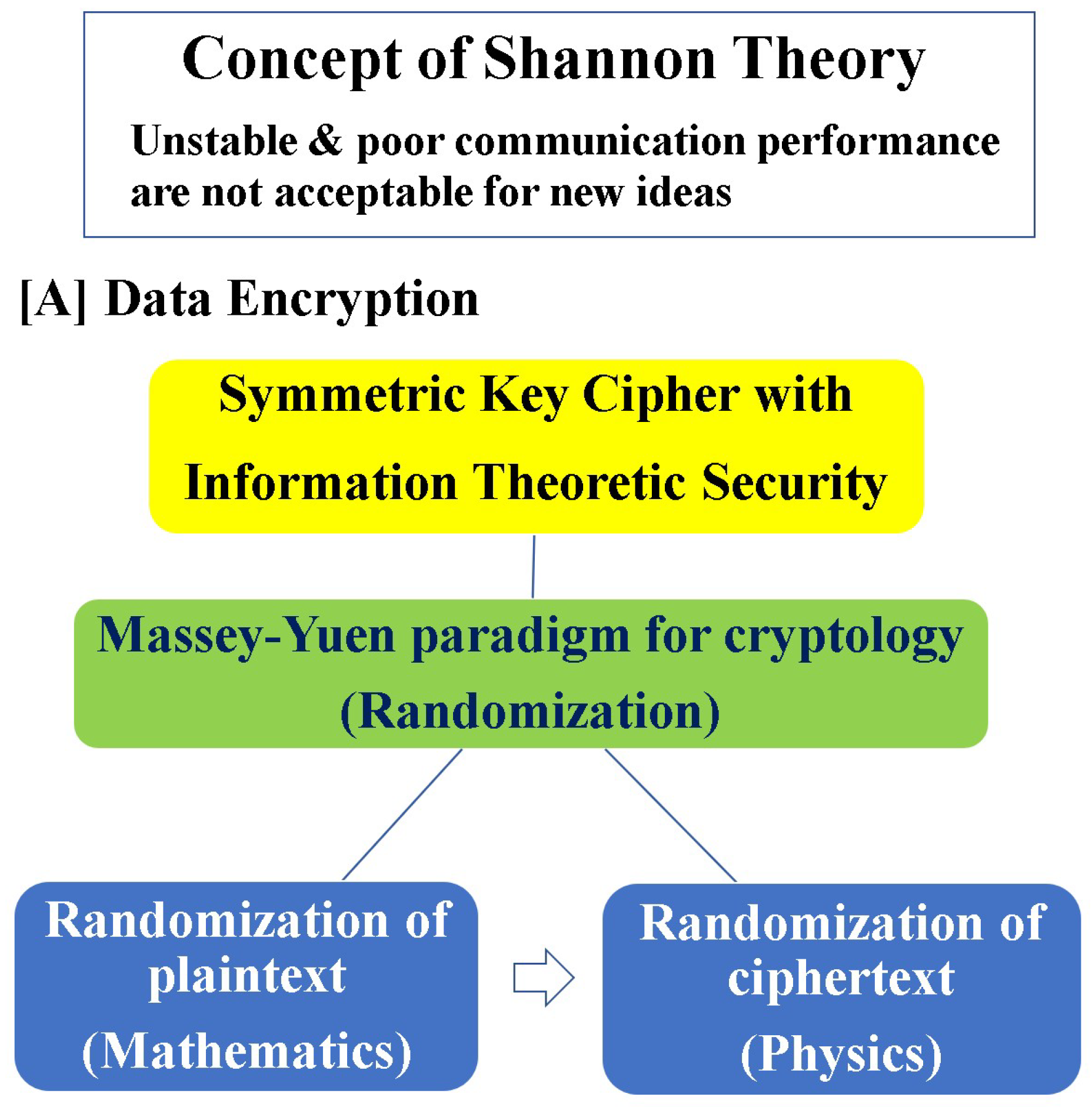

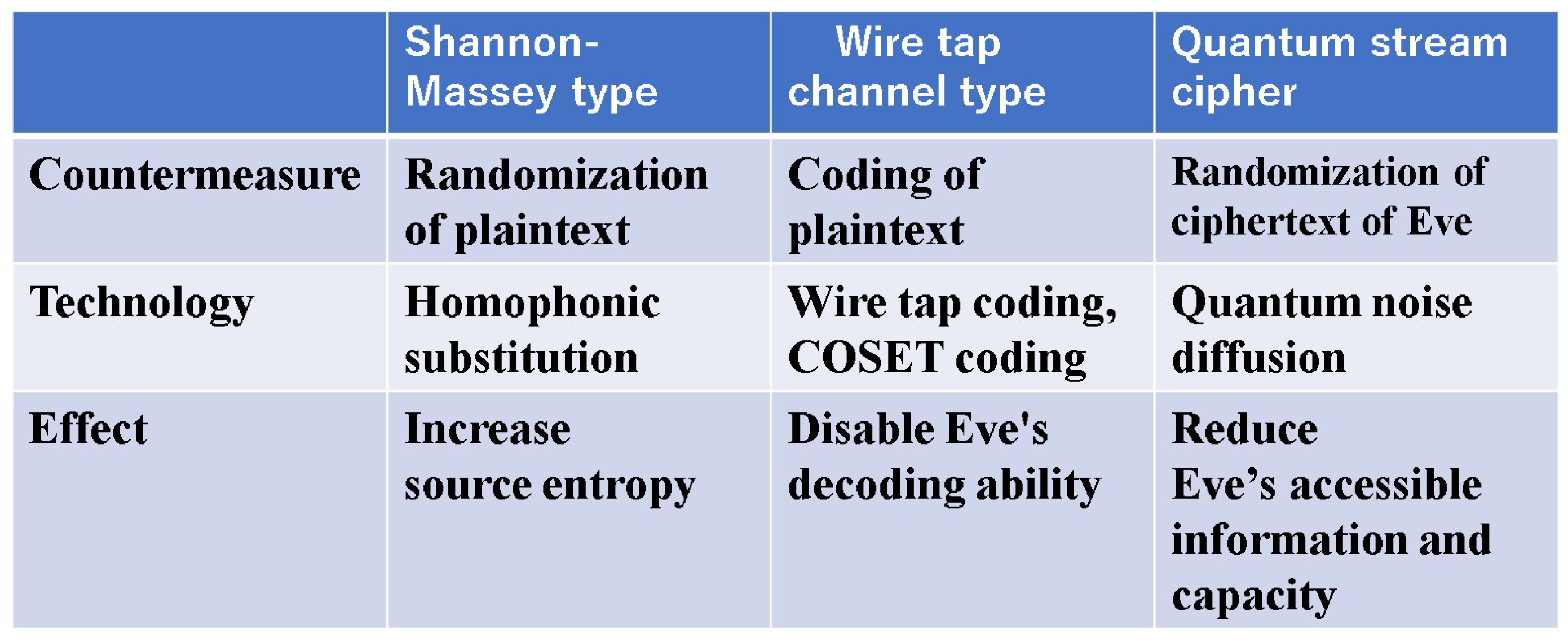

7. Discovery of a Cipher That Breaks the Shannon Impossibility Theorem

7.1. New Principle for Ciphers

7.2. Optical Quantum Modulation as Encryption Based on the New Principle

- (i)

- The sender prepares a big number of communication bases consisting of two non-orthogonal states (coherent state with high power) such aswhere . One of them is selected by using a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) with a secret key.

- (ii)

- The sender then transmits binary data using the selected binary communication basis.where is the random mapping function due to the same PRNG (see [51]).

- (iii)

- A receiver who has the same pseudorandom number with the key can identify the communication basis, so they always receive binary signals with small error, because the signal amplitude of binary coherent states is large enough.

- (i)

- A set of with different elements is prepared.

- (ii)

- One is selected from the set using a pseudorandom sequence with the secret key .

- (iii)

- A quantum ciphertext is generated by a unitary transformation associated with the selected as follows.

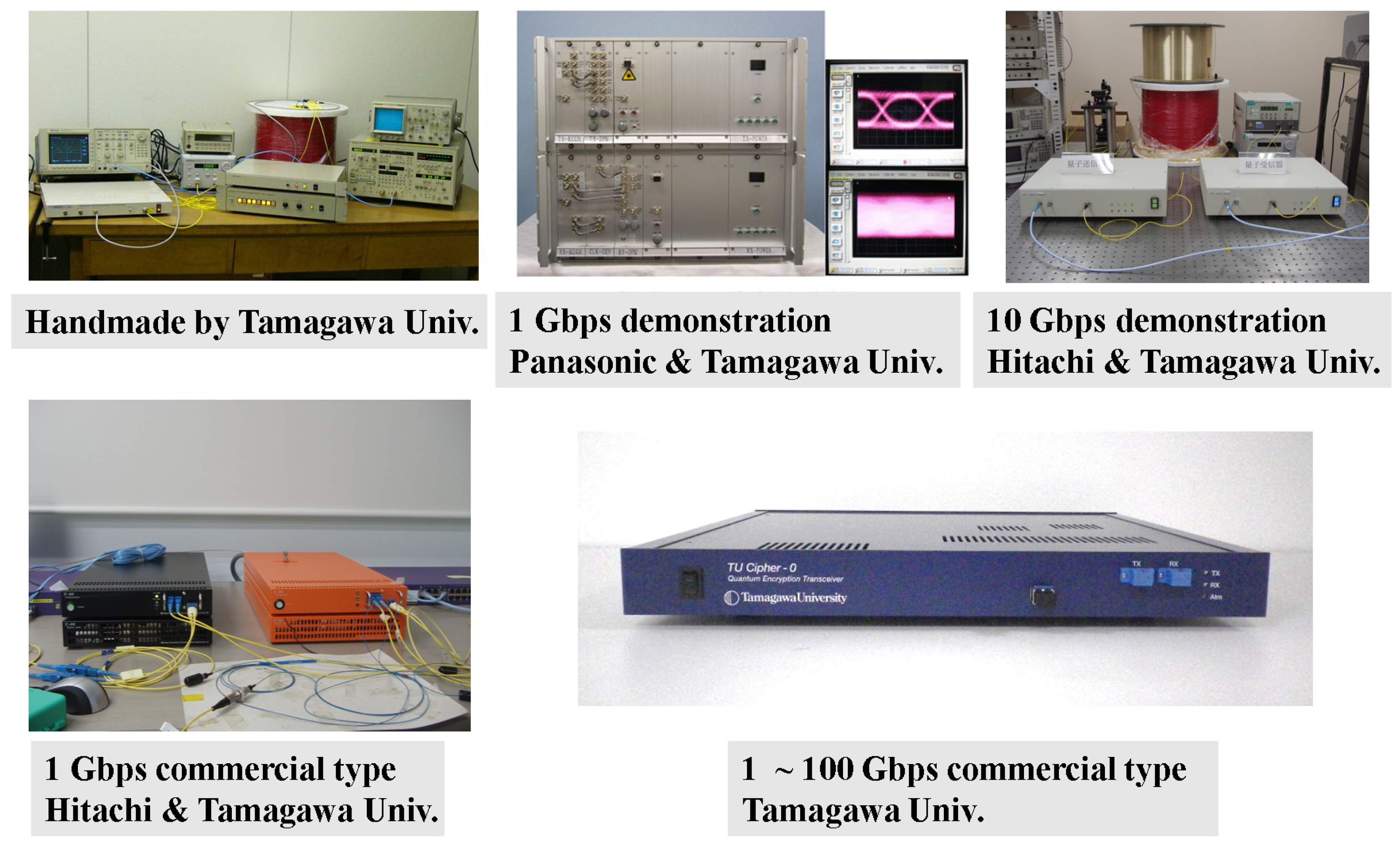

7.3. Social Implementation

7.3.1. Development of Transceiver for Quantum Stream Cipher

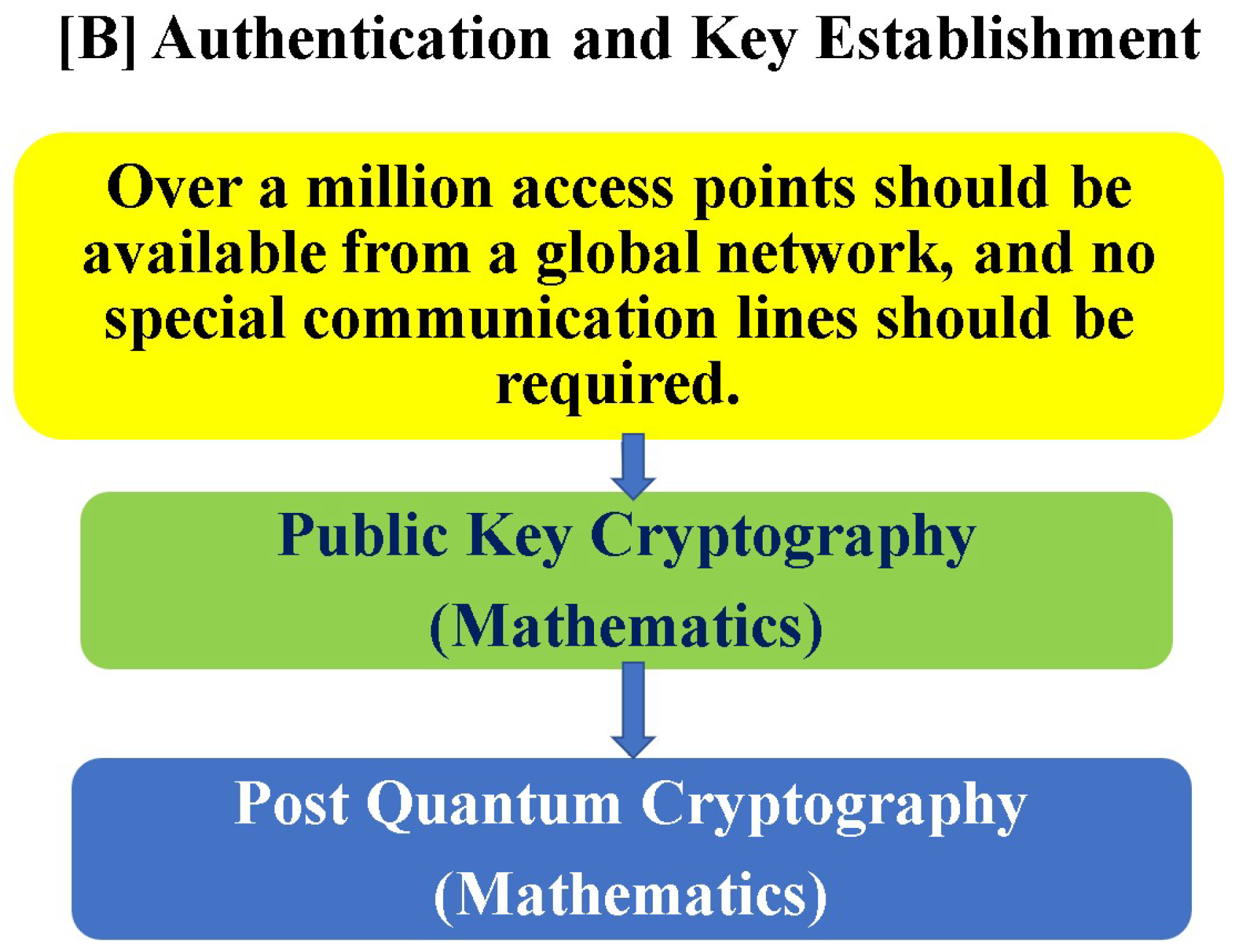

7.3.2. Application to Global Optical Network of 100 Gbit/s of Quantum Stream Cipher

7.3.3. Business for Quantum Stream Cipher Service

8. Sensor Applications Beyond the Standard Quantum Limit

8.1. Bell State Based on Entangled Coherent State

8.2. Quantum Reading Scheme

8.3. Error-Free Sensor Applicable to Reaction Control

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

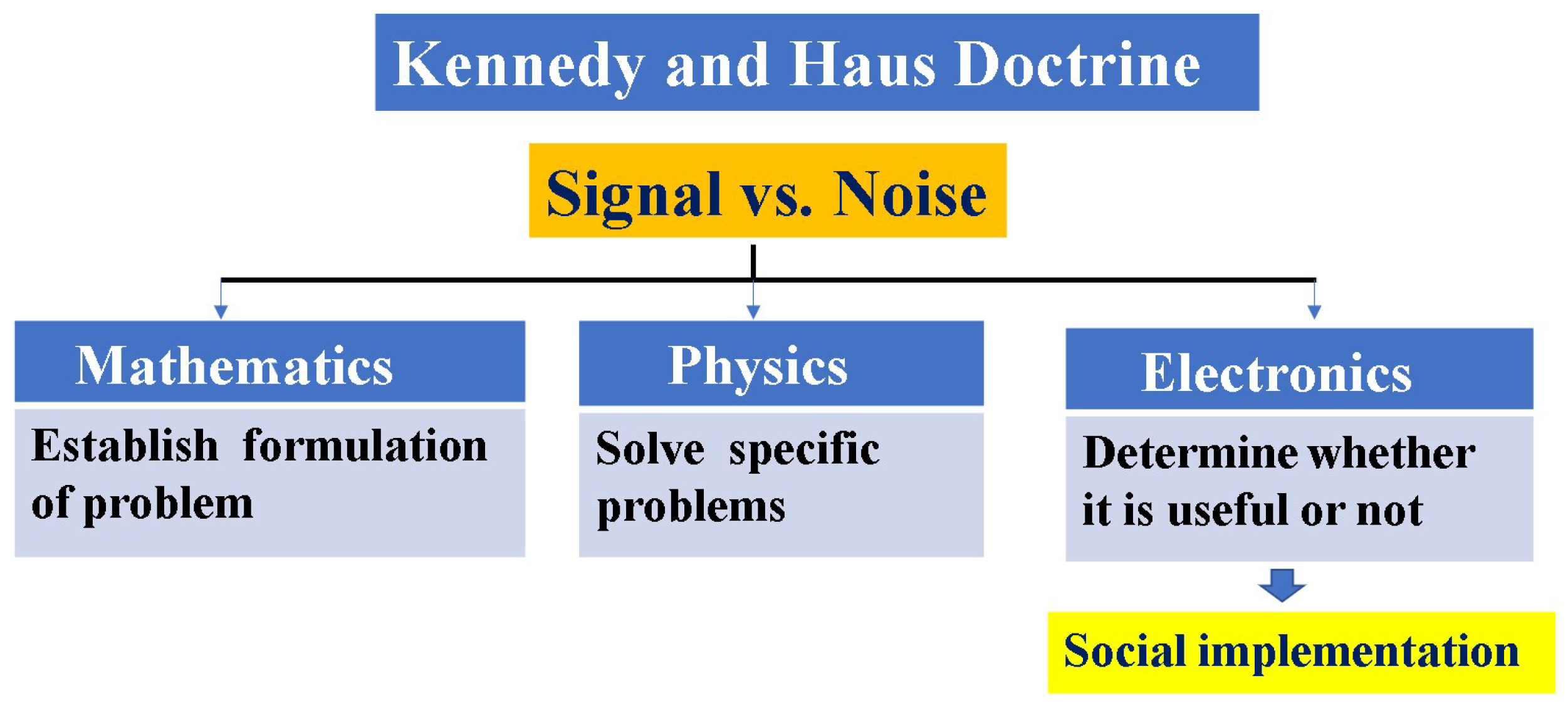

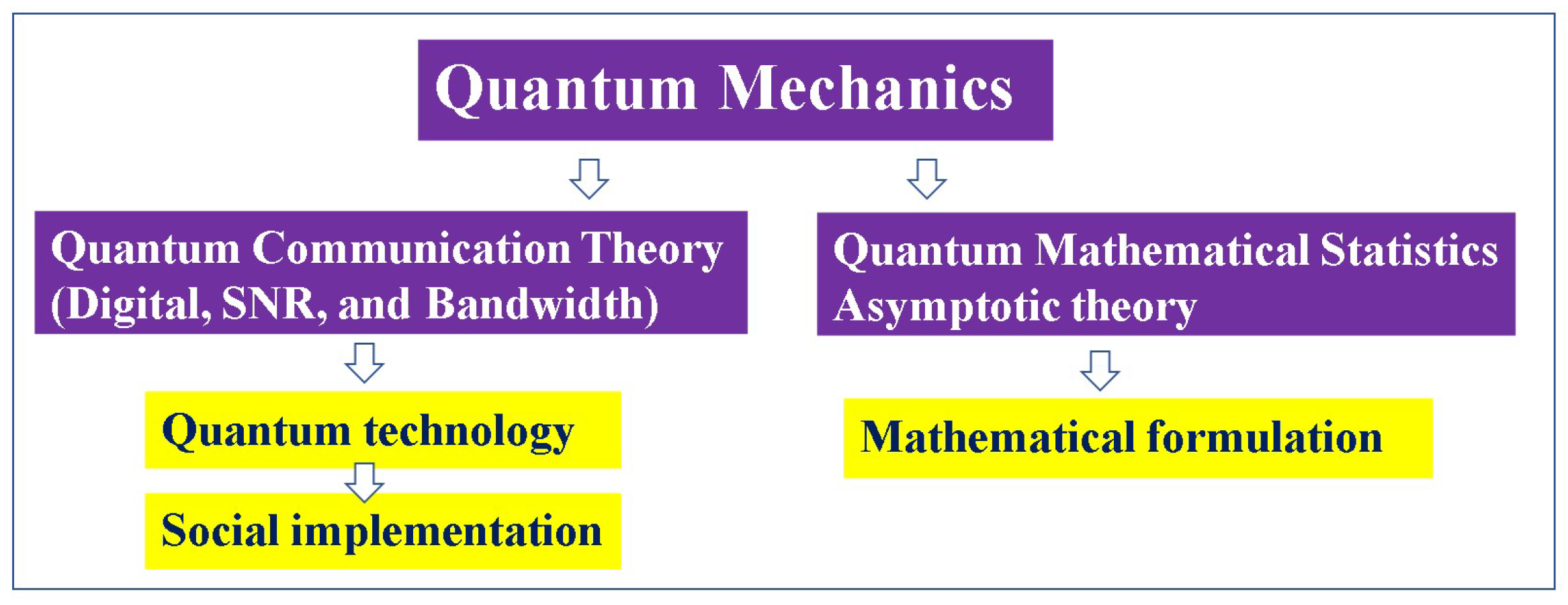

Appendix A. Towards Social Implementation of Quantum Technology

Appendix B. Towards Further Development of Theory

Appendix C. Quantum Shannon Information Transmission Theory

- R.L. Stratonovich, Theory of information and its value.

- R.G. Gallager, Principle of digital communication.

- G.C. Papen and R. Blahut, Lightwave communications.

- J. Perina, Quantum statistics of linear and nonlinear optical phenomena.

- I.B. Djordjeviv, Quantum communication, quantum networks and quantum sensing.

- G. Cariolaro, Quantum communications.

- L. Cohen, H.V. Poor, and M.O. Scully, Classical, semiclassical and quantum noise.

- M. Ohya and D. Petz, Quantum entropy and its use.

Appendix D. Towards the Development of Quantum Ciphers for Global Optical Networks

References

- Helstrom, C.W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Holevo, A.S. Statistical decision theory for quantum systems. J. Multivar. Anal. 1973, 3, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Kennedy, R.S.; Lax, M. Optimum testing of multiple hypotheses in quantum detection theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1975, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausladen, P.; Jozsa, R.; Schumacher, B.; Westmoreland, M.; Wootters, W. Classical information capacity of a quantum channel. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 54, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holevo, A.S. The capacity of the quantum channel with general signal state. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1998, 1, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.; Westmoreland, M. Sending classical information via noisy quantum channels. Physical. Rev. A 1997, 56, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallager, R.G. Information Theory and Reliable Communication; Wileys: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev, M.V.; Holevo, A.S. On reliability function of quantum communication channel. Probl. Peredachi Inform. 1988, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Holevo, A.S. Reliability function of general classical-quantum channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2000, 46, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helstrom, C.W.; Charbit, M.; Bendjaballah, C. Cut off rate performance for phase shift keying modulated coherent state. Opt. Commun. 1987, 64, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendjaballah, C.; Charbit, M. Quantum communication with coherent states. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1989, 35, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbit, M.; Bendjaballah, C.; Helstrom, C.W. Cut off rate for the M-ary PSK modulation channel with optimal quantum detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1989, 35, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Hirota, O. Cut-off rate for quantum communication channels with entangled measurement. Quantum Semiclass Opt. 1998, 10, L7–L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Hirota, O. Cut-off rate performance of quantum communication channels with symmetric signal states. J. Opt. B Quantum Semiclass Opt. 1999, 1, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S. Quantum Systems, Channels, Information, 2nd ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Helstrom, C.W. The conversion of a pure state into a statistical mixture by the linear quantum channel. Opt. Commun. 1981, 37, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S. Probabilistic and Statistical Aspects of Quantum Theory; North-Holland Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, A. Statistical Decision Function; Wileys: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C.A. Notes on a Paulian Idea: Foundational, Historical, Anecdotal and Forward-Looking Thoughts on the Quantum. arXiv 2001, arXiv:quant-ph/0105039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Non-causality and quantum communication theory. Tamagawa Univ. Res. Rev. 1995, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, O.; Ikehara, S. Minimax strategy in the quantum detection theory and its application to optical communications. Trans. IEICE Jpn. 1982, 65E, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Belavkin, V.P. Optimal multiple quantum statistical hypothesis testing. Stochastics 1975, 1, 315–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Ban, M.; Hirota, O. Derivation and physical inter pretation of the optimum detection operators for coherent state signals. Phys. Rev. A 1996, 54, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Momose, R.; Hirota, O. Quantum measurements for discrimination among symmetric quantum states and parameter estimation. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1997, 36, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M.G.A. Quantum estimation for quantum technology. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 2009, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personick, S.D. Application of quantum estimation theory to analog communication over quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1971, 17, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P.; Lax, M. Multiple-parameter quantum estimation and measurement of non-self adjoint observables. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1973, 19, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Generalized quantum measurement process and its application to quantum communication theory. Trans. IECE Jpn. 1977, 60A, 701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, H.P. States that give the maximum signal to quantum noise ratio for a fixed energy. Phys. Lett. 1976, 56A, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.B. Information and quantum measurement. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1978, 24, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Barnett, S.M.; Jozsa, R.; Osaki, M.; Hirota, O. Accessibleinformation and optimum strategies for real symmetrical quantum sources. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 59, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Hirota, O.; Ban, M. The maximum mutual information without coding for binary quantum states. J. Mod. Opt. 1998, 45, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Kato, K.; Izutsu, M.; Hirota, O. Quantum channels showing superadditivity in classical capacity. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Osaki, M.; Hirota, O. Derivation of classical capacity of quantum channel for discrete information source. Phys. Lett. A 1999, 251, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S.; Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Capacity of quantum Gaussian channels. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 59, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Information capacity formula of quantum optical channels. Recent Res. Dev. Opt. 2001, 1, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanenetti, V.; Guha, S.; Lloyd, S.; Maccone, L.; Shapiro, J.H.; Yuen, H.P. Classical capacity of lossy Bosonic channels: Exact solutionquantum Gaussian channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 027902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, J.R.; van Enk, S.J.; Fuchs, C.A. Experimental proposal for achieving superadditive communication capacities with a binary quantum alphabet. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 032309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.; Giobannetti, V.; Maccone, L. Sequential projective measurements for channel decoding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 250501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S. Structured optical receivers to attain super-additive capacity and the Holevo limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 240502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.W.; Guha, S.; Zheng, L. Capacity of optical communications over a lossy Bosonic channel with a receiver employing the most general coherent electro-optic feedback control. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 012320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. A foundation of quantum channels with super additiveness for Shannon information. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2000, 10, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.W.; Guha, S.; Zheng, L. Super additivity of Quantum Channel Coding Rate with Finite Block length Quantum Measurements. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2016, 62, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Binary discretization for quantum continuous channels. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 62, 52312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, K.; Hirota, O. Property of quantum reliability function and its applications toseveral quantum signals. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 2001, 84 Pt 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A.S.; Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Error exponents for quantum channels with constrained inputs. Rep. Math. Phys. 2000, 46, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.P. KCQ: A new approach to quantum cryptography I. General principles and key generation. arXiv 2003, arXiv:quant-ph/0311061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

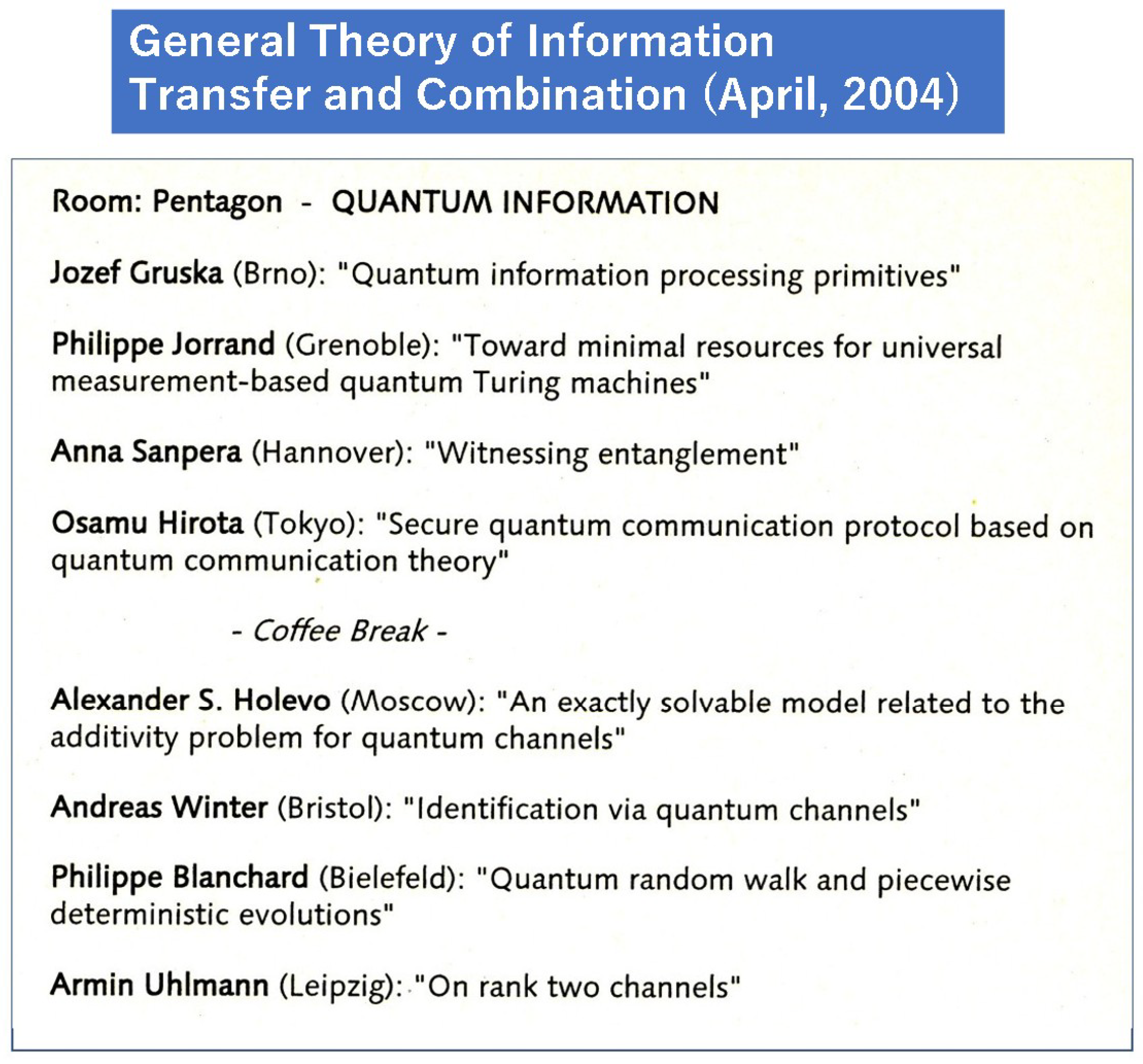

- Hirota, O. Secure quantum communication protocol based on quantum communication theory. In Proceedings of the General Theory of Information Transfer and Combination, Bielefeld, Germany, 15 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Quantum stream cipher based on Holevo-Yuen theory; part I. Entropy 2022, 24, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, O.; Sohma, M. Quantum stream cipher based on Holevo-Yuen theory: Part II. Entropy 2024, 26, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Design of quantum stream cipher—Part I; Lifting the Shannon impossibility theorem. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2025.14872v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Yuen, H.P.; Corndolf, E.; Kumar, P. Quantum noise randomized ciphers. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 052309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O.; Kurosawa, K. Immunity against correlation attack on quantum stream cipher by Yuen 2000 protocol. Quantum Inf. Process. 2007, 6, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Coherent Pulse Position Modulation Quantum Cipher Supported by Secret Key. Bull. Quantum ICT Res. Inst. Tamagawa Univ. 2011, 1, 15–19. Available online: https://www.tamagawa.jp/research/quantum/bulletin/2011.html (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Sohma, M.; Hirota, O. Masking property of quantum random cipher with phase mask encryption. Quantum Inf. Process. 2014, 13, 2221–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Quantum stream cipher and quantum block cipher—The Era of 100 Gbit/sec real-time encryption-. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.17240. [Google Scholar]

- Borbosa, G.A.; Corndolf, E.; Kumar, P.; Yuen, H.P. Secure communication using coherent state. In Proceedings of QCMC-2002; Shapiro, J.H., Hirota, O., Eds.; Rinton Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Borbosa, G.A.; Corndorf, E.; Kumar, P.; Yuen, H.P. Secure communication using mesoscopic coherent states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 227901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, G.S.; Reillly, D.; Smith, N. Practical physical layer encryption:The marriage of optical noise with traditional cryptography. IEEE Commun. Magajin 2009, 47, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futami, F.; Tanizawa, K.; Kato, K. Field Trial of Y-00 Quantum Stream Cipher System with Functions of Authentication and Key Distribution by Post-Quantum Cryptography. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEICE Japan Society Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 29 November–1 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K.; Futami, F.; Tanizawa, K. Quantum-enhanced secure-link architecture with quantum stream cipher Y-00 and post-quantum cryptography: Basic structure and experiment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Volume 12692, Quantum Communications and Quantum Imaging XXI, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–22 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Futami, F.; Tanizawa, K.; Kato, K. Transmission of Y-00 Quantum Noise Stream Cipher with Quantum Deliberate Signal Randomization over Field-Installed Fiber. Bull. Quantum ICT Res. Inst. Tamagawa Univ. 2023, 13, 23–25. Available online: https://www.tamagawa.jp/research/quantum/bulletin/2023.html (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Chen, X.; Tanizawa, K.; Winzer, P.; Dong, P.; Cho, J.; Futami, F.; Kato, K.; Melikyan, A.; Kim, K.W. Experimental demonstration of 4,294,967,296-QAM based Y-00 quantum stream cipher template carrying 160-Gb/s 16-QAM signals. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 5658–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Song, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Huang, L.; Cheng, M.; Liu, D.; Deng, L. Secure 100 Gb/s IMDD Transmission over 100 km SSMFenabled by quantum noise stream cipher and sparse RLS-Volterra Equalizer. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 63585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, L.; Zhong, Y.Q.; Deng, L.; Liu, D.; Dai, X.; Gao, X.; Cheng, M. Device-compatible ultra-high-order quantum noise stream cipher based on delta-sigma modulator and optical chaos. Nat. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.K.; Pang, H.Y.; Luo, Q.S.; Zhang, X.; Tao, Z.Y.; Fan, Y.X. Quantum noise stream cipher based on optical digital to analog conversion. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2025, 57, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizawa, K.; Futami, F. Ultra-long-haul digital coherent PSK Y-00 quantum stream cipher transmission system. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 10451–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O.; Sasaki, M. Entangled state based on nonorthogonal state. In Quantum Communication, Computing, and Measurement 3; Tombesi, P., Hirota, O., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- van Enk, S.J.; Hirota, O. Entangled coherent states: Teleportation and decoherence. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 022313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirandola, S. Quantum reading of a classical digital memory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 090504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O.; Suematsu, Y. Noise properties of injection lasers due to reflected waves. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1979, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, O. Error free quantum reading by quasi Bell state of entangled coherent states. Quantum Meas. Quantum Metrol 2017, 4, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Umegaki, H. Conditional expectation in an operator algebra, VI (entropy and information). Kodai Math. Sem. Rep. 1962, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.B. Quantum Theory of Open Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa, M. Quantum measuring processes of continuous observables. J. Math. Phys. 1984, 25, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M. Measurement breaking the standard quantum limit for free mass position. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 60, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, M. Quantum measurement theory for systems with finite dimensional state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.03219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belavkin, V.P. Quantum Stochastics and Information; World Scientific: Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Belavkin, V.P.; Hirota, O.; Hudson, R.L. Quantum Communications and Measurement; Plenum Press (Springer): New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, H.P. Two-photon coherent state of the radiation fields. Phys. Rev. A 1976, 13, 2226–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.C. Entangled coherent state. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 46, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourjoumtsev, A.; Ferreyrol, F.; Tualle-Brouri, R.; Grangier, P. Preparation of non-local superposition of quasi-classical light state. Nat. Phys. 2009, 5, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J. Quantum information processing for a coherent superposition state via a mixed entangled coherent channel. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 052308. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Jeong, H. Entangled coherent states versus entangled photon pairs for practical quantum-information processing. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 86, 062325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, Y.C.; Forney, G.D., Jr. On quantum detection and the square-root measurement. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001, 47, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chefles, A.; Barnett, S.M. Optimum unambiguous discrimination between linearly independent symmetric states. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 250, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirandola, S.; Lupo, C.; Giovannetti, V.; Mancini, S.; Braunstein, S.L. Quantum reading capacity. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, K.; Kato, K.; Usuda, T. Minimax strategy in quantum signal detection with inconclusive results. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 032314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, K.; Kato, K.; Usuda, T. Generalized quantum state discrimination problems. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 91, 052304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahira, K.; Kato, K. Generalized quantum process discrimination problems. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 062606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helstrom, C.W.; Kennedy, R.S. Noncommuting observables in quantum detection and estimation theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1974, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baras, J.S.; Hargar, R.O.; Park, Y.H. Quantum mechanical linear filtering of random signal sequence. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1976, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalai, M. Lower bounds on the probability of error for classical and classical-quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. A note on the reliability function for M-ary PSK coherent state signal. Bull. Quantum ICT Res. Inst. Tamagawa Univ. 2018, 1, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Usuda, T.S.; Takumi, I.; Hata, M.; Hirota, O. Minimum error detection of classical linear code sending through a quantum channel. Phys. Lett. A 1999, 256, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratonovich, R.L. Theory of Information and Its Value; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gallager, R.G. Principle of Digital Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Papen, G.C.; Blahut, R.E. Lightwave Communications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perina, J. Quantum Statistics of Linear and Nonlinear Optical Phenomena; D.Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Djordjeviv, I.B. Quantum Communication, Quantum Networks and Quantum Sensing; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cariolaro, G. Quantum Communications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Poor, H.V.; Scully, M.O. (Eds.) Classical, Semiclassical and Quantum Noise; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ohya, M.; Petz, D. Quantum Entropy and Its Use; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, J. Contemporary Cryptology—An Introduction; Simmons, G.J., Ed.; IEEE Press: Piscateville, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Blahut, R.E. Cryptography and Secure Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, D. Codes and Cryptography; Oxford Science Publications: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization. 2020. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 15 April 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirota, O. Quantum Shannon Information Theory—Design of Communication, Ciphers, and Sensors. Entropy 2025, 27, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111158

Hirota O. Quantum Shannon Information Theory—Design of Communication, Ciphers, and Sensors. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111158

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirota, Osamu. 2025. "Quantum Shannon Information Theory—Design of Communication, Ciphers, and Sensors" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111158

APA StyleHirota, O. (2025). Quantum Shannon Information Theory—Design of Communication, Ciphers, and Sensors. Entropy, 27(11), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111158