An Improved Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree and Its Application to Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Entropic Chaos Degree

3. Extended Entropic Chaos Degree

- (1) Points inare uniformly distributed over.

- (2) Then,is obtained for any.

4. Improvement of Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree

5. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps

5.1. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Generalized Baker’s Map

5.2. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Tinkerbell Map

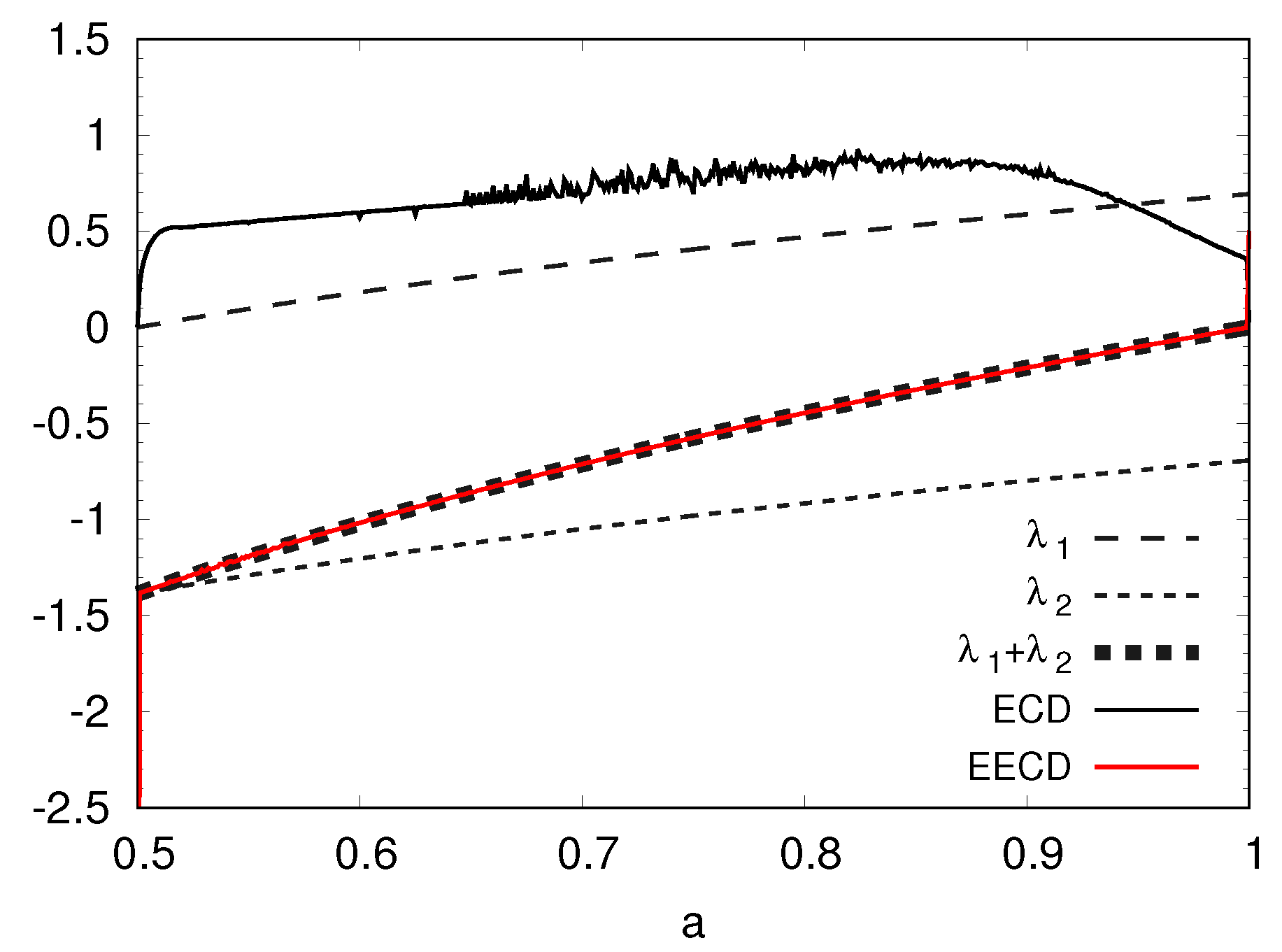

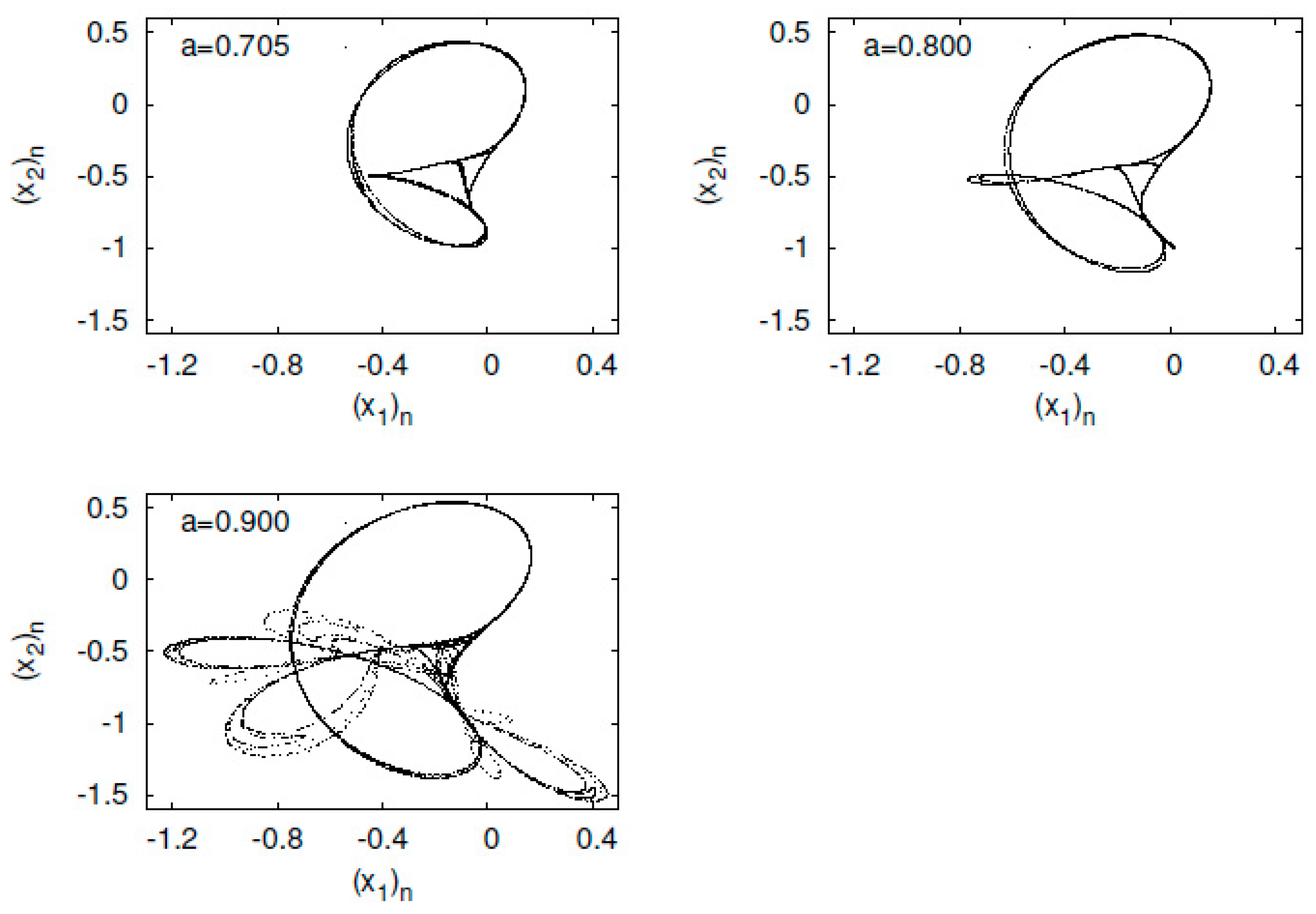

5.3. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Ikeda Map

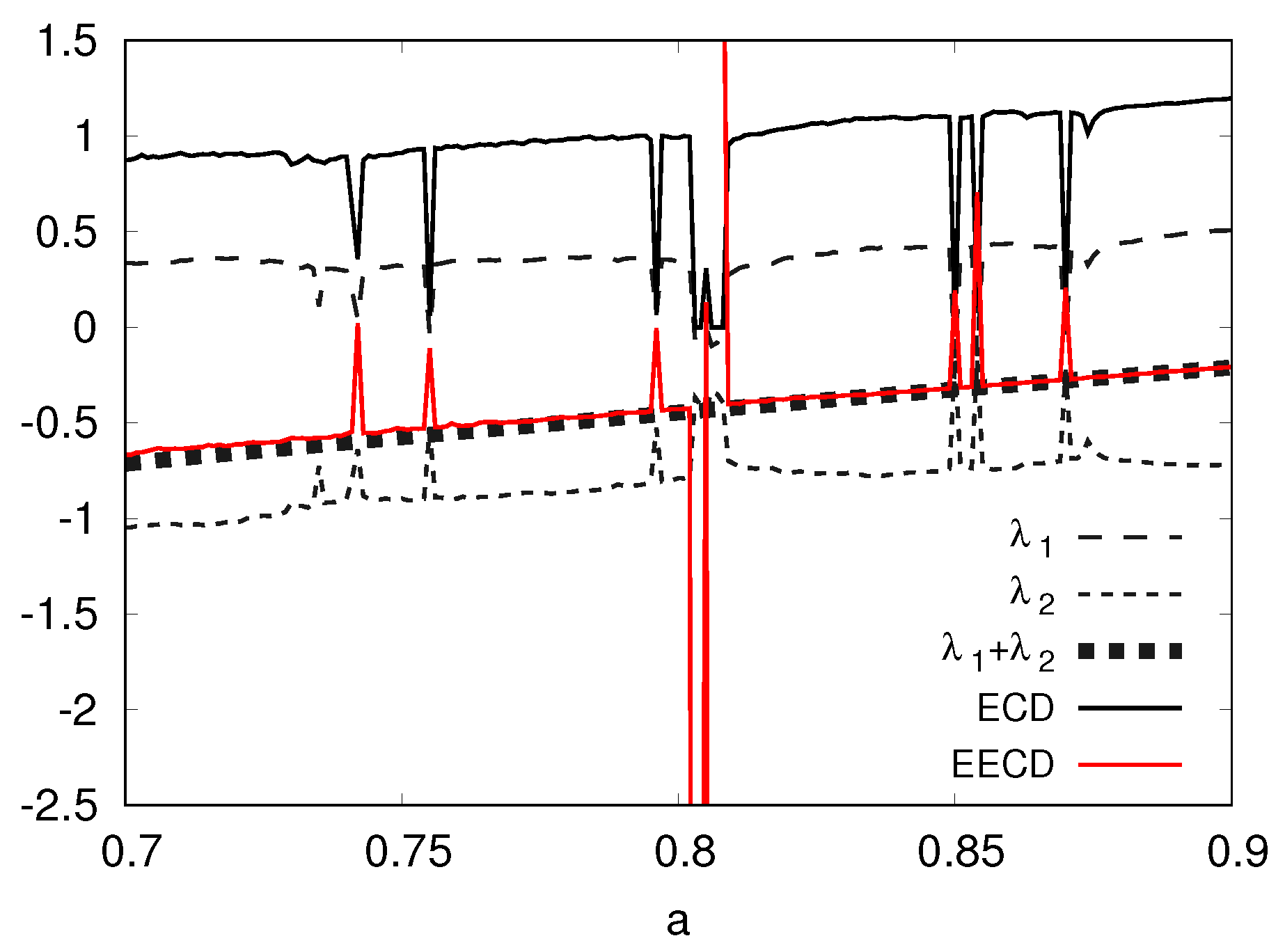

5.4. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Hénon Map

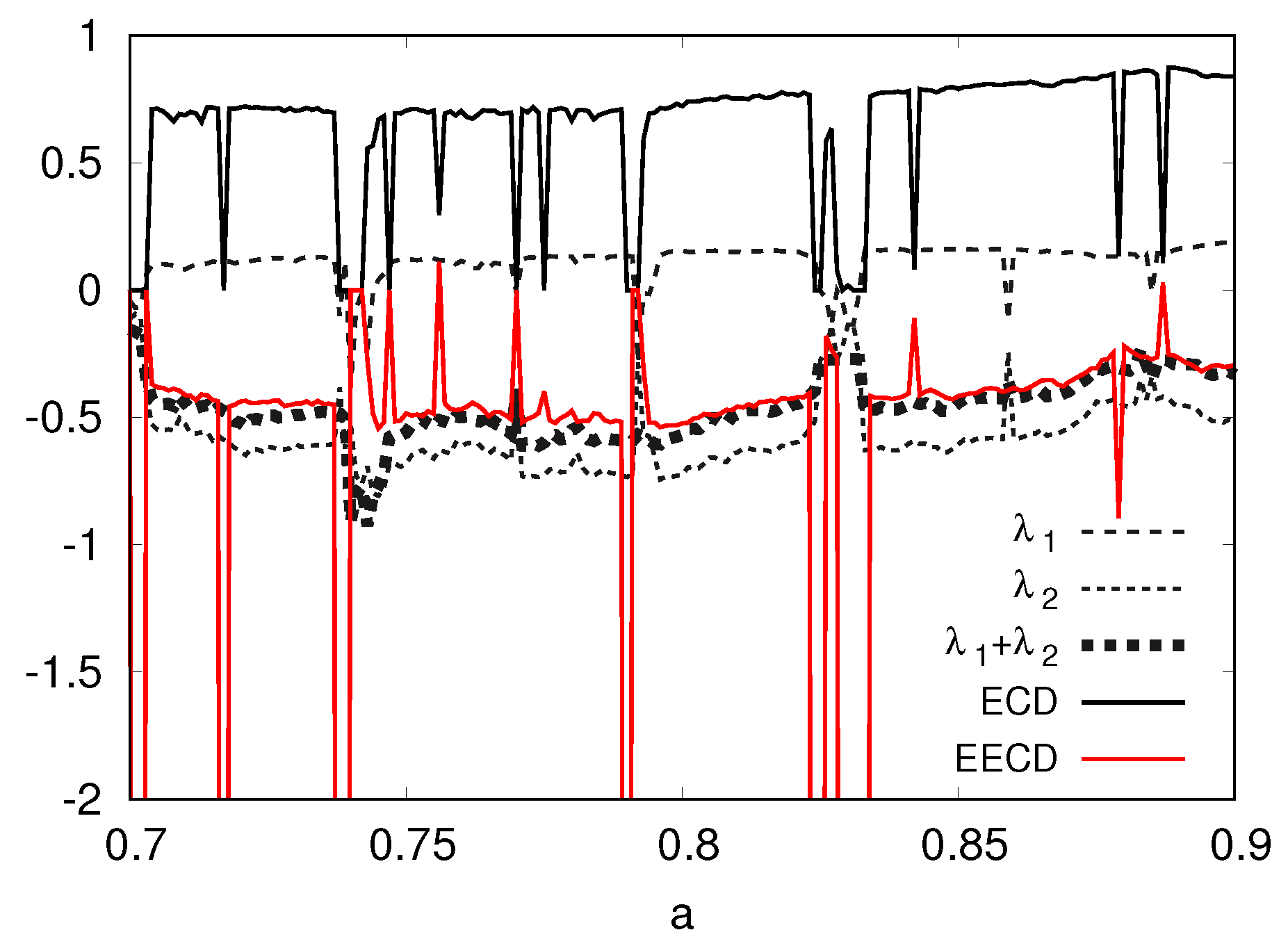

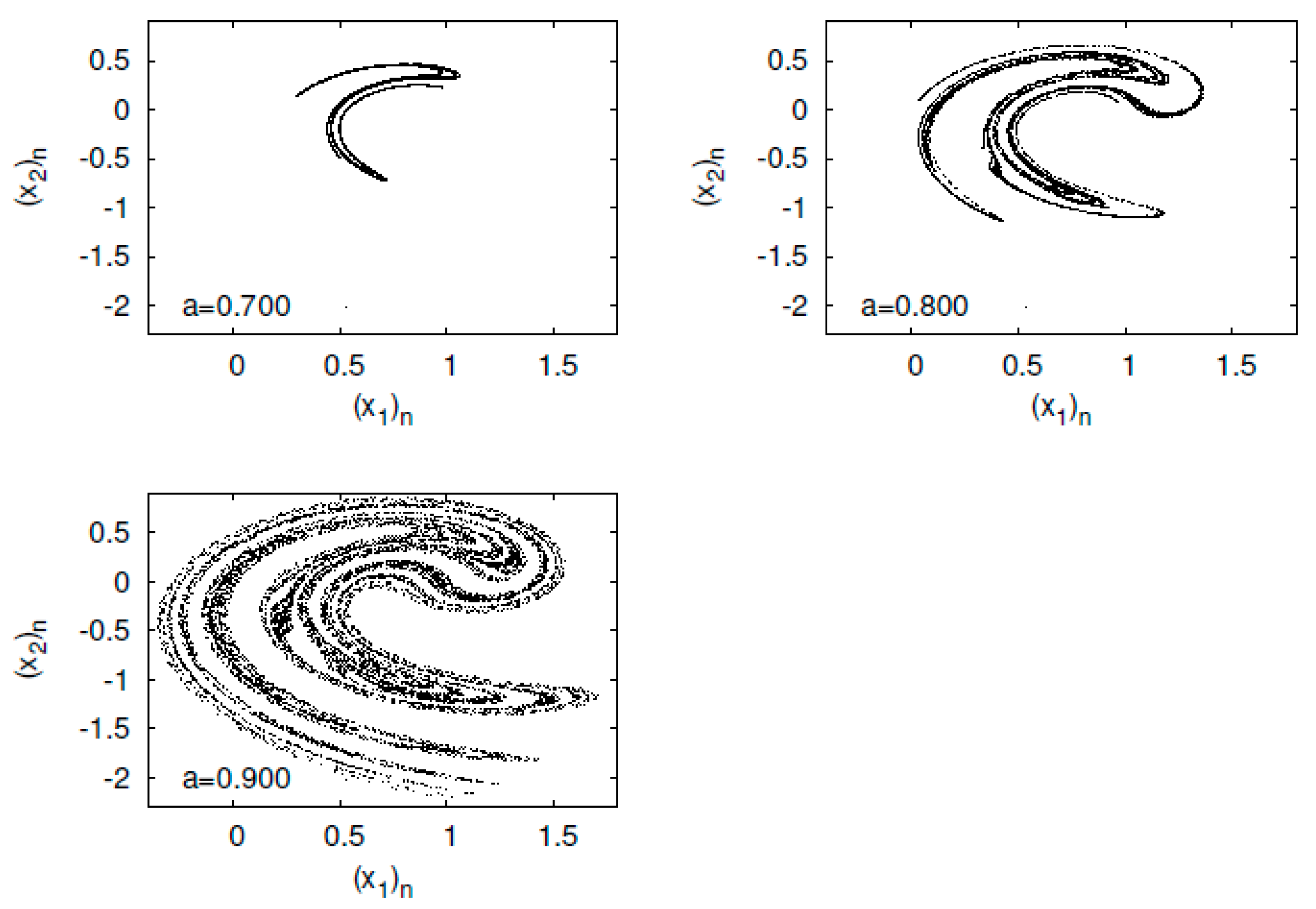

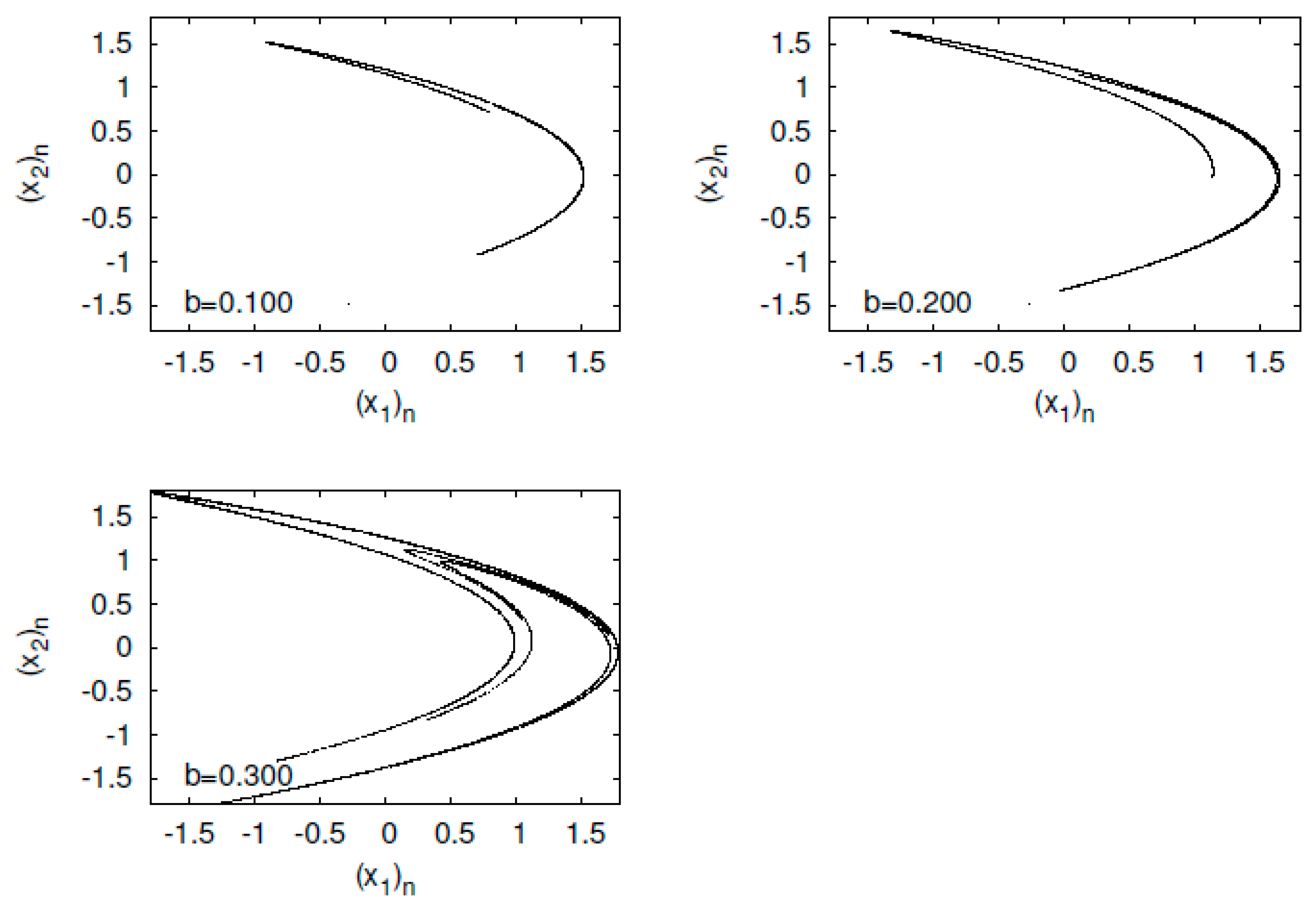

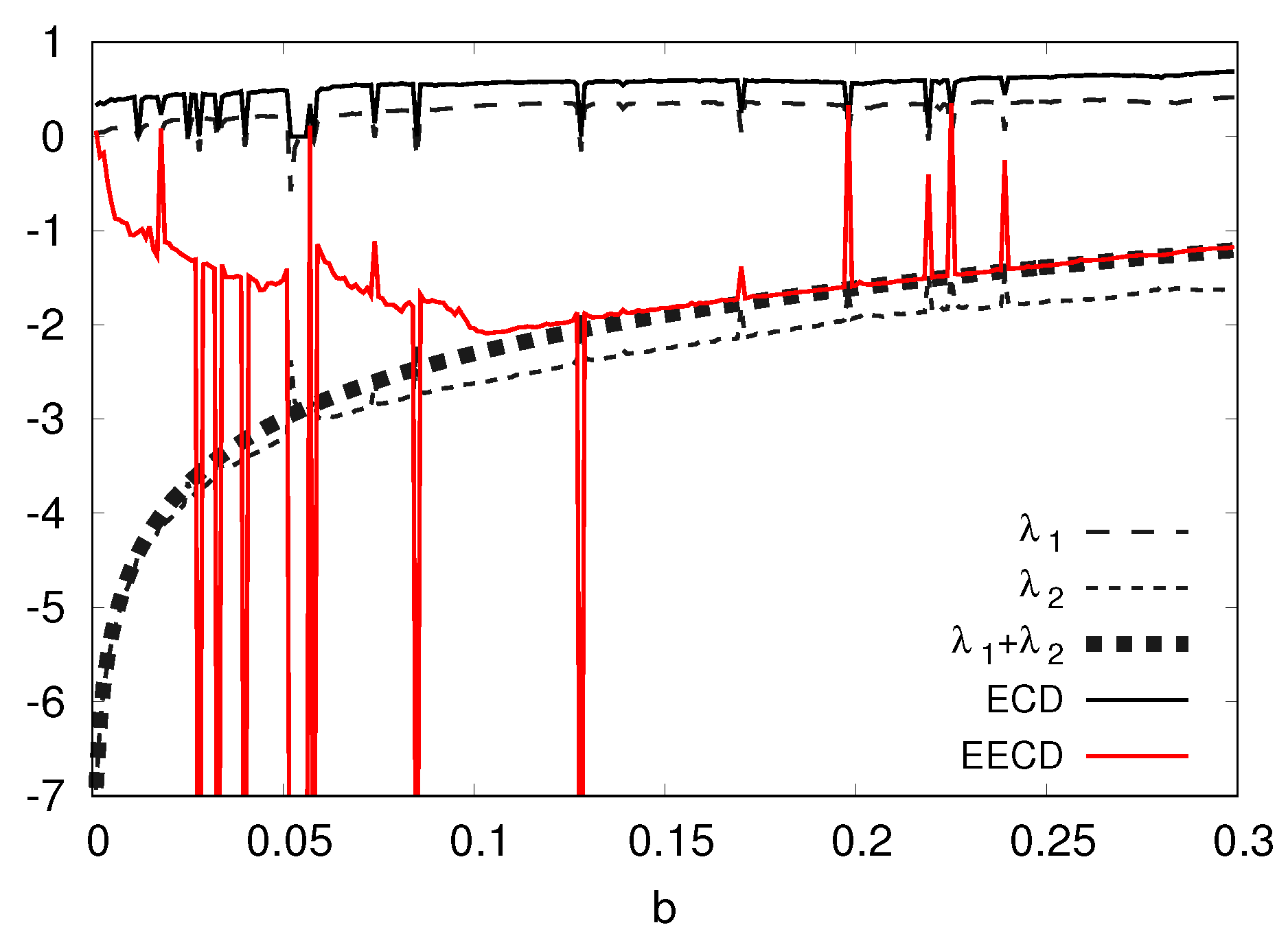

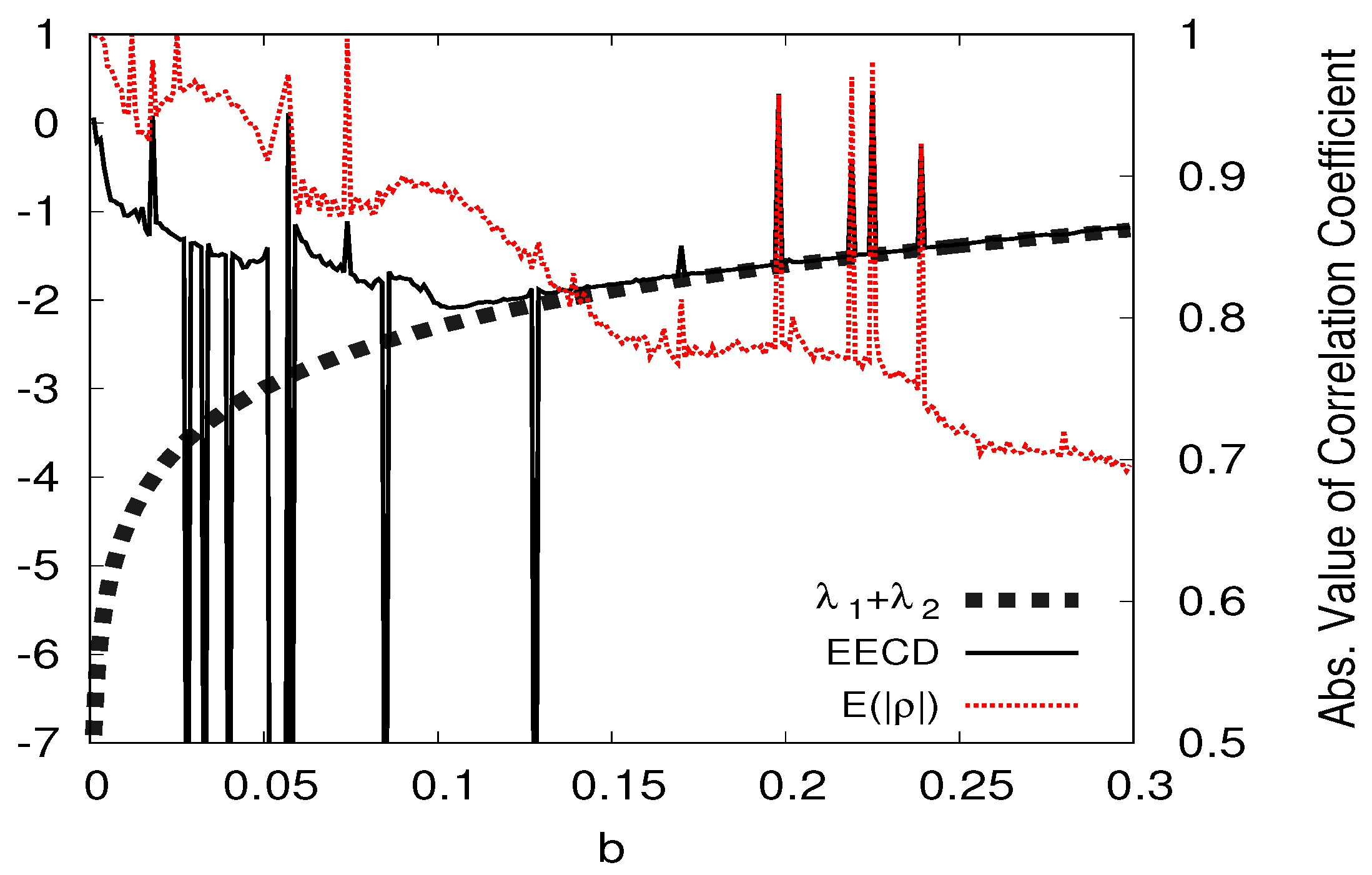

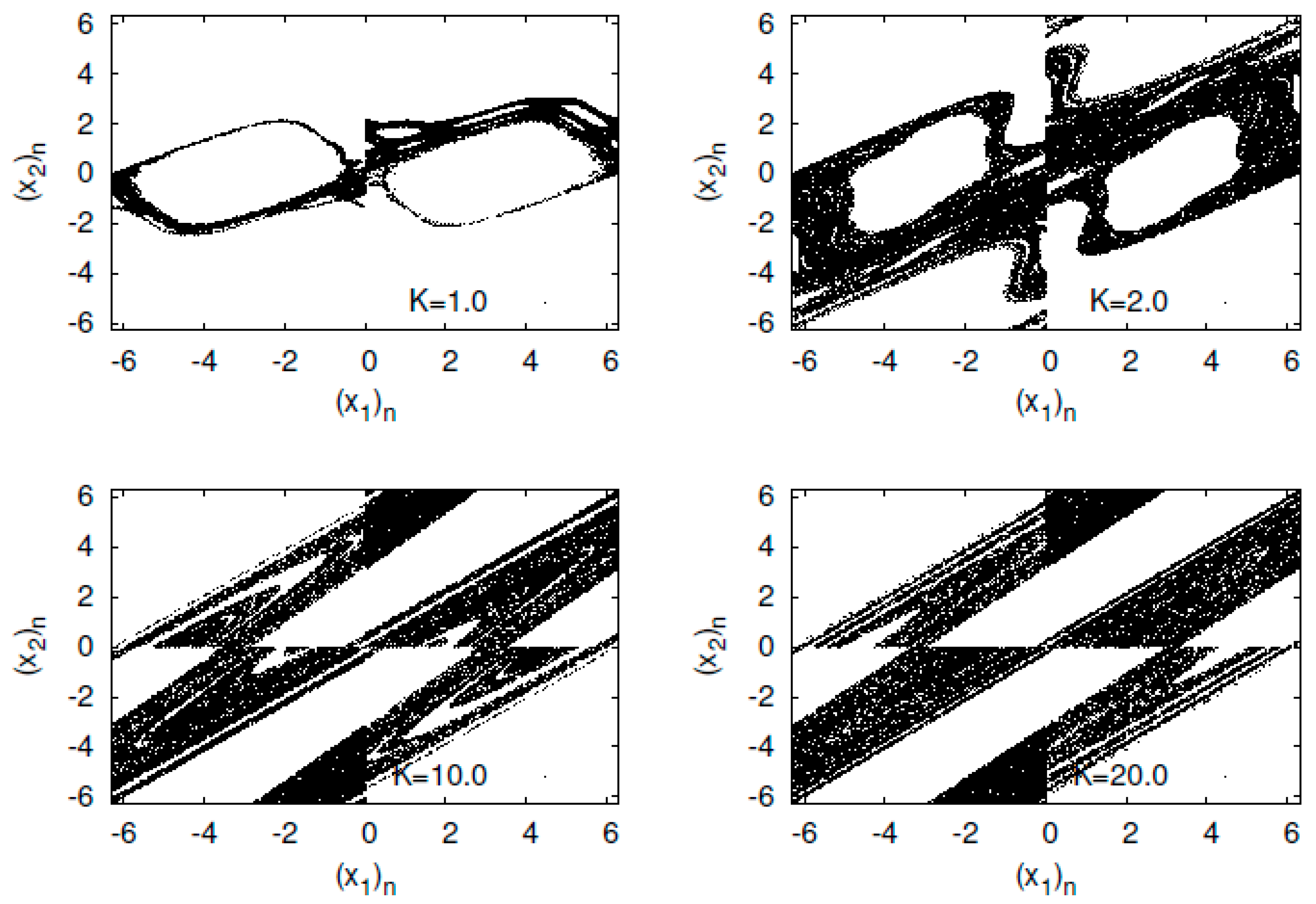

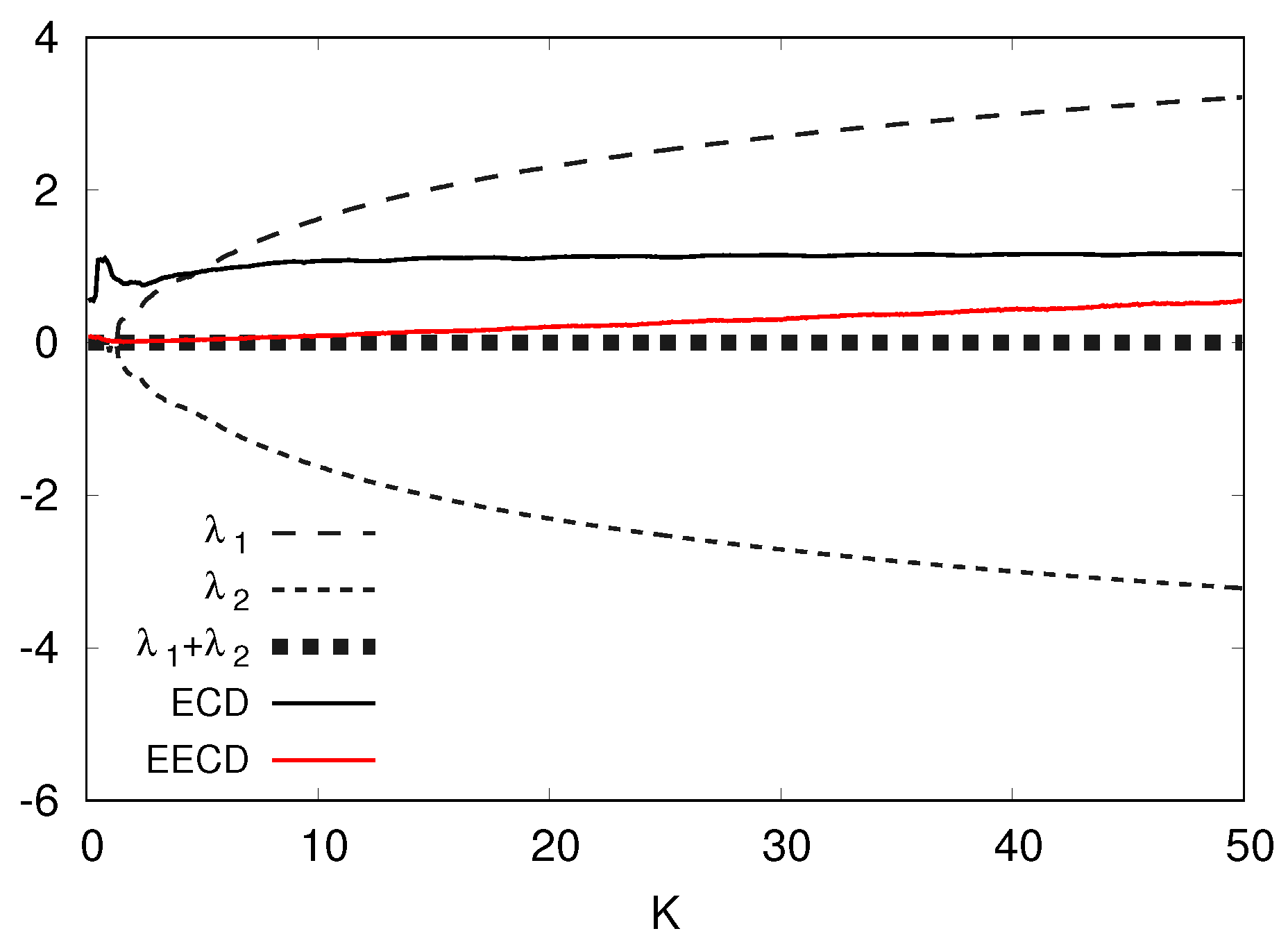

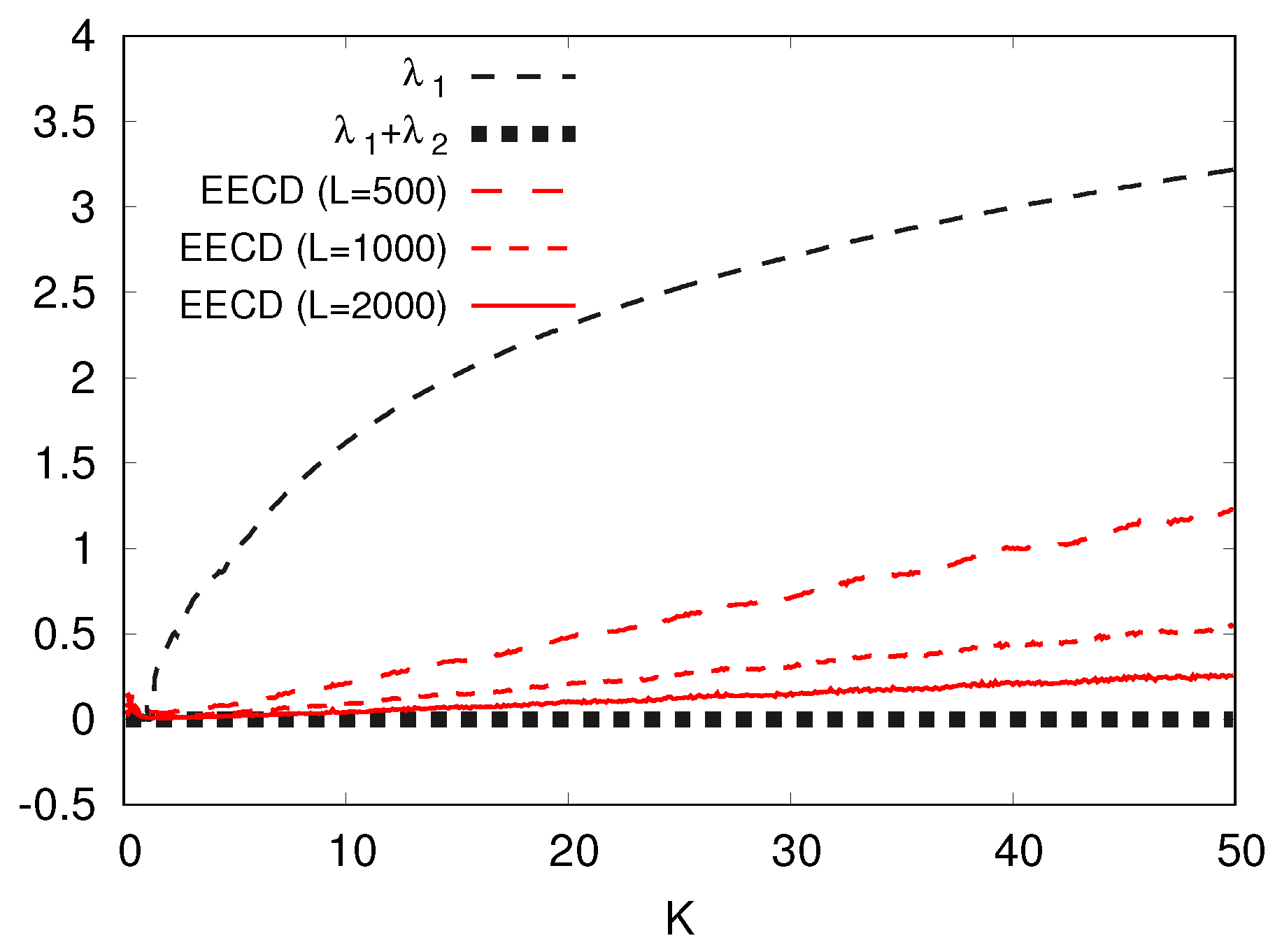

5.5. Numerical Computation Results of the EECD for Standard Map

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eckmann, J.P.; Kamphorst, S.O.; Ruelle, D.; Ciliberto, S. Lyapunov exponents from time series. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 34, 4971–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstein, M.T.; Collins, J.J.; De Luca, C.J. A practical method for calculating largest Lyapunov exponents from small data sets. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 1993, 65, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Sano, M.; Sawada, Y. Practical methods of measuring the generalized dimension and the largest Lyapunov exponent in high dimensional chaotic systems. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1987, 77, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, M.; Sawada, Y. Measurement of the Lyapunov spectrum from a chaotic time series. Phys. Let. A 1995, 209, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J. Method for calculating a Lyapunov exponent. Phys. Rev. A 1984, 29, 2924–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.; Swift, J.B.; Swinney, H.L.; Vastano, J.A. Determining Lyapunov exponents from a time series. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 16D, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, M. Complexities and their applications to characterization of chaos. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1998, 37, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ohya, M.; Sato, K. Application of chaos degree to some dynamical systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2000, 11, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ohya, M.; Volovich, I. Semiclassical properties and chaos degree for the quantum baker’s map. J. Math. Phys. 2002, 43, 734–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ohya, M.; Volovich, I. On a combined quantum baker’s map and its characterization by entropic chaos degree. Open Syst. Inf. Dyn. 2009, 16, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Okutomi, H.; Umeno, K. Investigation of the difference between Chaos Degree and Lyapunov exponent for asymmetric tent maps. JSIAM Lett. 2019, 11, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Okutomi, H.; Umeno, K. Proposal of improved chaos degree based on interpretation of the difference between chaos degree and Lyapunov exponent. Trans. JSIAM 2019, 29, 383–394. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, K.; Mao, T.; Okutomi, H.; Umeno, K. An extension of the entropic chaos degree and its positive effect. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 2021, 38, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, L. Ergodic Theory, Hyperbolic Dynamics and Dimension Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, K. Multiple-valued stationary state and its instability of the transmitted light by a ring cavity system. Opt. Commun. 1979, 30, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Daido, H.; Akimoto, O. Optical Turbulence: Chaotic Behavior of Transmitted Light from a Ring Cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Oksasoglu, A. Rank one chaos: Theory and applications. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2008, 18, 1261–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.S.W.; Roberts, A.G. Time-reversal symmetry in dynamical systems: A survey. Phys. D 1998, 112, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.G.; Quispel, G.R.W. Chaos and time-reversal symmetry. Order and chaos in reversible dynamical systems. Phys. Rep. 1992, 216, 63–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, M.; Carvalho, M.; Rodrigues, A. Generic area-preserving reversible diffeomorphisms. Nonlinearity 2015, 28, 1695–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inoue, K. An Improved Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree and Its Application to Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps. Entropy 2021, 23, 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23111511

Inoue K. An Improved Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree and Its Application to Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps. Entropy. 2021; 23(11):1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23111511

Chicago/Turabian StyleInoue, Kei. 2021. "An Improved Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree and Its Application to Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps" Entropy 23, no. 11: 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23111511

APA StyleInoue, K. (2021). An Improved Calculation Formula of the Extended Entropic Chaos Degree and Its Application to Two-Dimensional Chaotic Maps. Entropy, 23(11), 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23111511