Abstract

Suppose that a d-dimensional Hilbert space admits a full set of mutually unbiased bases , where . A randomized quantum state tomography is a scheme for estimating an unknown quantum state on through iterative applications of measurements for , where the numbers of applications of these measurements are random variables. We show that the space of the resulting probability distributions enjoys a mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation structure, which provides us with a simple geometrical insight into the maximum likelihood method for the quantum state tomography.

1. Introduction

Quantum state tomography is a method of estimating an unknown quantum state represented on some Hilbert space , consisting of a fixed set of measurements that provides sufficient information about the unknown quantum state, as well as a data processing that maps each measurement outcome into the quantum state space on [1]. A set of measurements that fulfils this requirement is sometimes called a measurement basis. For mathematical simplicity, we restrict ourselves to Hilbert spaces of finite dimensions.

To elucidate our motivation, let us treat the simplest case when . It is well known that there is a one-to-one affine correspondence between the qubit state space

and the unit ball (called the Bloch ball)

In fact, the correspondence is explicitly given by the Stokes parametrization

where , , and are the standard Pauli matrices. Since for , the set of observables is regarded as an unbiased estimator [2,3,4] for the Stokes parameter . This is the basic idea behind the standard qubit state tomography, which runs as follows: suppose that, among N independent experiments, the ith Pauli matrix was measured times, and outcomes (spin-up) and (spin-down) were obtained and times, respectively. Then a naive estimate for the true value of the parameter is

When the estimate falls outside the Bloch ball B, it needs to be corrected so that the new estimate lies in the Bloch ball B. The maximum likelihood method is a canonical one to obtain a corrected estimate [2,5,6,7,8,9,10]. From the point of view of information geometry [11,12,13], the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) is the orthogonal projection from the temporary estimate onto the Bloch ball B with respect to the standard Fisher metric along the -geodesic [14], (cf., Appendix A).

Now let us deal with a slightly generalized situation: suppose that the ith Pauli matrix was measured times and outcomes and were obtained and times, respectively, where were random variables. Such a situation arises in an actual experiment due to unexpected particle loss [15]. We shall call such a generalized estimation scheme a randomized state tomography. A naive estimate in this case is the following:

One may invoke the maximum likelihood method when falls outside the Bloch ball. It is then interesting to ask if there is also a useful geometrical picture for the MLE even when the numbers of measurements are random variables.

The above mentioned problem is naturally extended to quantum state tomography on an arbitrary Hilbert space that admits a full set of mutually unbiased bases [16,17]. In a d-dimensional Hilbert space , k orthonormal bases

are called mutually unbiased if they satisfy

for all with , and . It is known that the number k of mutually unbiased bases (MUBs) is at most [18]. If there are MUBs, the Hilbert space is said to admit a full set of MUBs. For example, when the dimension d of is a power of a prime, admits a full set of MUBs [19]. Whether or not any Hilbert space admits a full set of MUBs is an open question [16].

In what follows, unless otherwise stated, we assume that the Hilbert space under consideration admits a full set of MUBs. As demonstrated in Appendix B (cf., [17,20]), each density operator can be uniquely represented as

where

is the projection-valued measure (PVM) associated with the ath orthogonal basis in the MUBs, and

is a -dimensional real parameter that is chosen so that . A simple calculation shows that, if the ath measurement is applied to the state , one obtains each outcome with probability

This implies that the parametrization establishes an affine isomorphism between the quantum state space

and the convex set

Incidentally, the Stokes parametrization for the qubit state space is regarded as a special case of the above parametrization for . In fact, the eigenvectors of the Pauli matrices , , form a full set of MUBs on , and the Stokes parametrization is related to the above parametrization as

Now that a standard affine parametrization has been established on an arbitrary Hilbert space that admits a full set of MUBs, the scheme of randomized state tomography is naturally extended to as follows. Suppose that the ath measurement was applied times and the outcome was obtained times, where were random variables. Then, due to (2), a naive estimate for the parameter is

When the estimate falls outside the parameter space B, one may invoke the maximum likelihood method to obtain a corrected estimate.

The objective of the present paper is to clarify that the -projection interpretation for the MLE is still valid for the randomized state tomography by changing the standard Fisher metric into a deformed one depending on the realization of the random variables , which might as well be called a randomized Fisher metric. Such a novel geometrical picture will provide important insights into the quantum metrology.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we first introduce a statistical model on an extended sample space that represents the randomized state tomography. We then clarify that the probability simplex is decomposed into mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation by means of certain - and -autoparallel submanifolds. In Section 3, we give a statistical interpretation of the above-mentioned dualistic foliation structure. In particular, we point out that the MLE is the -projection with respect to a deformed Fisher metric that depends on the realization of the random variables . These results are demonstrated by several illustrative examples in Section 4. Finally, some concluding remarks are presented in Section 5. For the reader’s convenience, some background information is provided in Appendix A and Appendix B, including information geometry of the MLE and affine parametrization of a quantum state space .

2. Geometry of Randomized State Tomography

We identify the randomized state tomography on with the following scheme [21]: at each step of the measurement, one chooses a PVM at random with probability , (), and applies the chosen PVM to yield an outcome . The sample space for this statistical picture is

Suppose that the unknown state is specified by the coordinate as (1). Then the corresponding probability distribution on is represented by the -dimensional probability vector

where the parameter belongs to the domain

Note that the family

with

forms a -dimensional open probability simplex , and the parameters form a coordinate system of . Since we are only interested in estimating the parameter , the remaining parameter is understood as a set of nuisance parameters [2,12]. In what follows, we regard as a statistical manifold endowed with the standard dualistic structure , where g is the Fisher metric, and and are the exponential and mixture connections [12].

Let us consider the following submanifolds of :

for each , and

for each . Since and are convex subsets of , they are both -autoparallel. In addition, we have the following.

Proposition 1.

For each , the submanifold is -autoparallel. Furthermore, for each and , the submanifolds and are mutually orthogonal with respect to the Fisher metric g.

Proof.

Let us change the coordinate system into , where

for , and

for . With this coordinate transformation, the probability vector is rewritten as

Here, is a function of defined by

and is not a component of the coordinate system . We see from the representation (3) that the coordinate system is -affine. The potential function for is given by the negative entropy

and the dual -affine coordinate system is given by

for , and

for . Thus, fixing is equivalent to fixing the coordinates , and the submanifold is generated by changing the remaining parameters . This implies that is -autoparallel, proving the first part of the claim.

To prove the second part, let us introduce a mixed coordinate system [11]

of . Since , the submanifold is rewritten as

On the other hand, the submanifold is rewritten as

Thus, the orthogonality of and is an immediate consequence of the orthogonality of the dual affine coordinate systems and with respect to the Fisher metric g. ☐

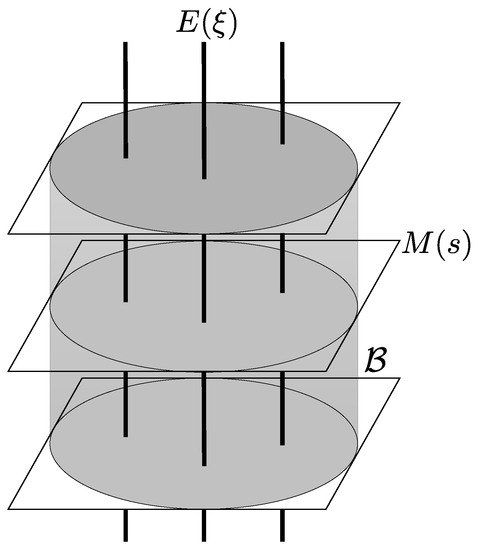

Proposition 1 implies that the manifold is decomposed into mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation based on the submanifolds and , as illustrated in Figure 1. We shall exploit this geometrical structure in the next section.

Figure 1.

Mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation of based on and . Each section is affinely isomorphic to the parameter space . The greyish cylindrical area indicates the subset of . In particular, for each , the intersection is affinely isomorphic to the physical domain B that corresponds to the state space .

3. Estimation of the Parameter

Let us proceed to the problem of estimating the unknown parameter using the randomized tomography. Suppose that, among N independent repetitions of experiments, the ath measurement was applied times and outcomes were obtained times. Then temporary estimates for the parameters are given by

for , and

for . If has fallen outside the physical domain B, one may seek a corrected estimate by the maximum likelihood method. Observe that, due to (2), the empirical distribution is represented as

On the other hand, the physical domain B in the parameter space corresponds to the subset

of , (see Figure 1). The MLE in is then given by

where is the Kullback-Leibler divergence (cf., Appendix A). A crucial observation is the following.

Proposition 2.

The minimum in (5) is achieved on .

Proof.

Let us take a point arbitrarily. It then follows from the mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation of established in Proposition 1 that

In the second equality, the generalized Pythagorean theorem was used. Consequently,

for all , and the right-hand side is achieved if and only if . ☐

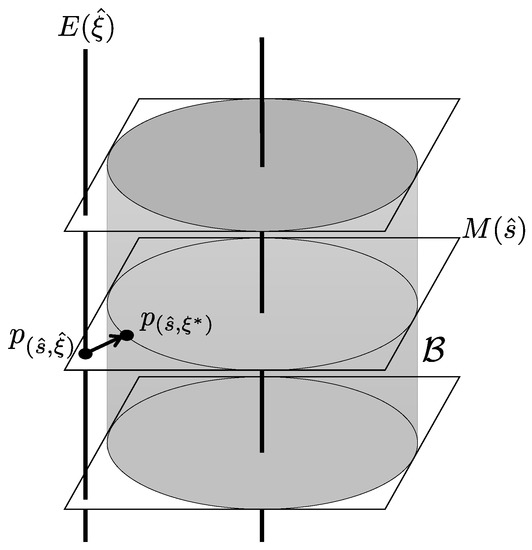

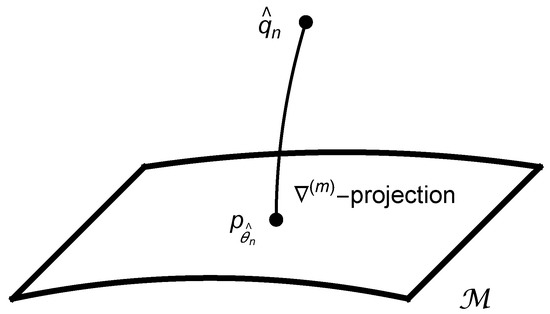

The geometrical implication of Proposition 2 is illustrated in Figure 2. The MLE is the -projection from the empirical distribution to , and is on the section specified by the temporary estimate .

Figure 2.

The maximum likelihood method in the framework of randomized tomography. Given a temporary estimate with , we can restrict ourselves to the section as the search space for the MLE , and is the -projection from the empirical distribution to on the section .

Now we arrive at a geometrical picture behind the parameter estimation based on randomized state tomography. Suppose we are given a temporary estimate with . Due to Proposition 2, we can restrict ourselves to section as the search space for the MLE . Since each section is affinely isomorphic to the parameter space , we can introduce a dualistic structure on in the following way. Firstly, we identify the metric with the Fisher metric g restricted on , that is,

for and , where and are formally defined as

Secondly, the mixture connection on is defined through the natural affine isomorphism between and . Finally, the dual connection is defined by the duality

Thus, the MLE in the parameter space is interpreted as the -projection from to the physical domain B with respect to the metric .

4. Examples

In this section, we present some examples that demonstrate the implication of Proposition 2 as well as the general diagram given in Figure 2.

4.1. When

Let us first study the simplest case when . A full set of MUBs is given by

With these bases, the parameter representation (1) becomes

where is the standard Stokes parameter, which is related to as for .

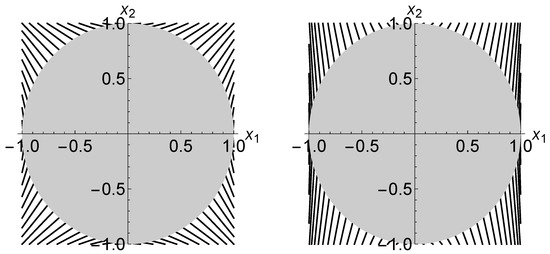

Figure 3 demonstrates how the -projection is realized. Here, the trajectories of -projections that gives the MLE are plotted only on the -plane. The left and right panels correspond to the cases when and , respectively. The change of -coordinate relative to the change of -coordinate along each trajectory is less noticeable in the right panel than in the left panel. This is because a tomography with provides us with more information about -coordinate, relative to -coordinate, as compared with the case when .

Figure 3.

The trajectories of -projections on the Stokes parameter space when (left) and (right). The greyish disk represents the Bloch ball B.

4.2. When

The space admits a full set of MUBs; for example,

where is a primitive third root of unity. With these bases, the parameter representation (1) becomes

where

The physical domain B that corresponds to the state space is a compact convex subset of the parameter space , and the extreme points of B form an algebraic variety with respect to the parameters

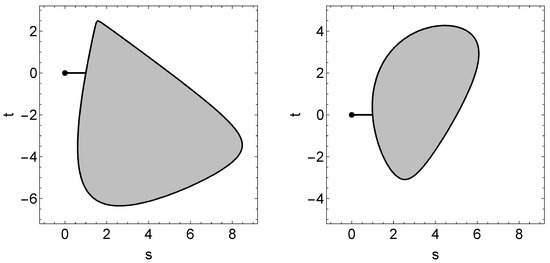

A numerical example of a -projection that gives the MLE is illustrated in Figure 4, where no probe particle is lost, that is, when

Figure 4.

A trajectory of -projection displayed on randomly chosen two-dimensional affine subspaces of to which both the empirical distribution (marked as a dot) and the MLE belong. The greyish region represents the physical domain B.

In Figure 4, the dot laid outside the greyish region indicates the empirical distribution, i.e., the temporary estimate

and the corresponding MLE is

Furthermore, the greyish region represents the physical domain B cut by a two-dimensional affine subspace of specified by the equation

The vector v was chosen randomly under the condition that

where the orthogonality ⊥ and the norm are understood relative to the standard Euclidean structure of . In Figure 4, the vector v was taken to be

in the left panel, and

in the right panel.

Figure 4 also demonstrates that the sections of the physical domain B show a variety of shapes. Unfortunately, due to this asymmetry of B, we were unable to find a (nontrivial) two-dimensional affine subspace on which every -projection runs. Such a difficulty is in good contrast to the simplest case , where the set B is rotationally symmetric and the -projections can be displayed on any two-dimensional section of B that passes through the origin of B as Figure 3.

4.3. When

The space is also known to admit a full set of MUBs since is the second power of the prime number 2; for example [22],

It is straightforward to calculate the parameter representation (1) of a state ; however, the corresponding density matrix is rather complicated, and we omit to display it here.

When , or more generally, when is not a power of a prime, we do not know whether admits a full set of MUBs. Let us touch upon a situation where a Hilbert space , if it exists, does not admit a full set of MUBs. In this case, there is no measurement basis that allows a parametrization of the state space having a direct connection to the probability distribution of the outcomes as (2). Such a situation could be comparable to the case when the Gell-Mann matrices [23] are used as the measurement basis for estimating an unknown state on . A state is represented as

where are the Gell-Mann matrices, and is a set of real parameters.

The physical domain

forms a compact convex subset of the unit ball in . With the state , the probability distribution of obtaining the eigenvalues of the observable is

while the probability distribution of obtaining the eigenvalues of the observable is

Note that the probability of obtaining the eigenvalue 0 of is identical to that of . However, in a randomized estimation scheme in which is measured times, the frequency of obtaining the eigenvalue 0 of would be different from that of . Consequently, one cannot assign a consistent temporary estimate for the parameter in that case. Put differently, the empirical distribution on the extended outcome space does not in general have a coordinate representation (4). Thus, the existence of a full set of MUBs is crucial in our analysis.

5. Concluding Remarks

In the present paper, we explored an information geometrical structure of the randomized quantum state tomography, assuming that the Hilbert space under consideration admits a full set of MUBs. We first introduced a classical statistical model on an extended sample space , and found that the probability simplex was decomposed into mutually orthogonal dualistic foliation (Proposition 1). We then clarified that this geometrical structure had a statistical importance in estimating the coordinate of an unknown quantum state under the existence of the nuisance parameter s (Proposition 2). This result gave a generalized insight into the -projection interpretation for the MLE in that a similar interpretation was still valid for the randomized quantum state tomography by changing the standard Fisher metric into a deformed one. It also provided us with a new, convenient way of data processing in the actual quantum state tomography that may involve unexpected probe particle loss.

It should be noted that the existence of a full set of MUBs ensures the parametrization (1) of the quantum state space . Such a parametrization is distinctive in that it enables a direct correspondence between the parameter space and the probability simplex, realizing the coordinate representation (4) of the empirical distribution . Thus, the use of a full set of MUBs is crucial in our analysis. Nevertheless, it is often the case that the Hilbert space under consideration takes the form for or 3 because qubits or qutrits are often regarded as building blocks of various quantum protocols. Therefore, the existence of a full set of MUBs would not be too strong a requirement in applications.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

The present study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP22340019 and JP17H02861.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ryo Okamoto and Shigeki Takeuchi for helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MUBs | mutually unbiased bases |

| PVM | projection-valued measure |

| MLE | maximum likelihood estimate |

Appendix A. Information Geometry of MLE

Let denote the set of probability distributions on a finite sample space , i.e.,

This set may be identified with the -dimensional (open) simplex, where denotes the number of elements in , and thus it is sometimes referred to as the probability simplex on . The set is also regarded as a statistical manifold endowed with the dualistic structure , where g is the Fisher metric, and and are the exponential and mixture connections [11,12,13].

Suppose that the state of the physical system at hand belongs to a (closed) subset of , but we do not know which is the true state. We further assume that the probability distributions of are faithfully parametrized by a finite dimensional parameter as

In this case, is called a parametric model, and our task is to estimate the true value of the parameter that specifies the true state. Suppose that, by n independent experiments, we have obtained data . This information is compressed into the empirical distribution, an element of defined by

for each , where is the Kronecker delta. If belongs to the model , then we have an estimate that satisfies . However, the empirical distribution does not always belong to the model . When , we need to find an alternative estimate from the data. A canonical method of finding an alternative estimate is the maximum likelihood method, in which one seeks the maximizer of the likelihood function

within the domain of the parameter , so that

We can rewrite this relation as follows.

where

is the Kullback-Leibler divergence from q to p. In other words, the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) is the point on that is “closest” from the empirical distribution as measured by the Kullback-Leibler divergence:

Due to the generalized Pythagorean theorem, the MLE is geometrically understood as the -projection from to or its boundary, as illustrated in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

The maximum likelihood estimate is the minimizer of the function with respect to , and is also understood as the -projection from the empirical distribution to or its boundary.

Appendix B. Parametrization of

Suppose that the Hilbert space under consideration admits a full set of MUBs

For each , let

Then, the operators

are linearly independent, spanning the space of selfadjoint operators with zero trace. This is easily seen from the orthogonality relation:

Thus, given , the operator is uniquely expanded as

where are real numbers. We can regard as a coordinate system of the state space . When , this is identical to the Stokes parametrization, up to a factor of 2.

Now, let us change the coordinate system into as

We then arrive at the parametrization (1), i.e.,

This parametrization is useful in our analysis because it gives a direct connection to the probability distribution of outcomes of the measurement as

References

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, E.L.; Casella, G. Theory of Point Estimation, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Helstrom, C.W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Holevo, A.S. Probabilistic and Statistical Aspects of Quantum Theory; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hradil, Z. Quantum-State Estimation. Phys. Rev. A 1997, 55, R1561–R1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszek, K.; D’Ariano, G.M.; Paris, M.G.A.; Sacchi, M.F. Maximum-likelihood estimation of the density matrix. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 61, 010304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hradil, Z.; Summhammer, J.; Badurek, G.; Rauch, H. Reconstruction of the spin state. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 62, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.F.V.; Kwiat, P.G.; Munro, W.J.; White, A.G. Measurement of qubits. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 052312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Burgh, M.D.; Langford, N.K.; Doherty, A.C.; Gilchrist, A. Choice of measurement sets in qubit tomography. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 052122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blune-Kohout, R. Optimal, reliable estimation of quantum states. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 043034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, S.-I.; Nagaoka, H. Methods of Information Geometry; Translations of Mathematical Monographs 191; AMS and Oxford: Charles Street, RI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.-I. Differential-Geometrical Methods in Statistics; Lecture Notes in Statistics 28; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.K.; Rice, J.W. Differential Geometry and Statistics; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, A.; Yamagata, K. Data processing for qubit state tomography: An information geometric approach. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1608.07983. [Google Scholar]

- Fraïsse, J.M.E.; Braun, D. Quantum channel-estimation with particle loss: GHZ versus W states. Quantum Meas. Quantum Metrol. 2016, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durt, T.; Englert, B.-G.; Bengtsson, I.; Życzkowski, K. On mutually unbiased bases. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 2010, 8, 535–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, G. Quantum state tomography via mutually unbiased measurements in driven cavity QED systems. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 043013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootters, W.K.; Fields, B.D. Optimal state-determination by mutually unbiased measurements. Ann. Phys. 1989, 191, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, I. Three ways to look at mutually unbiased bases. arXiv, 2006; arXiv:quant-ph/0610216. [Google Scholar]

- Ivonovic, I.D. Geometrical description of quantal state determination. J. Phys. A 1981, 14, 3241–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K. Efficiency of quantum state tomography for qubits. Int. J. Quantum Inform. 2011, 9, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klappenecker, A.; Rötteler, M. Constructions of mutually unbiased bases. arXiv, 2003; arXiv:quant-ph/0309120. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M. Symmetries of baryons and mesons. Phys. Rev. 1962, 125, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).