Abstract

In this paper we examine an Information-Theoretic method for solving noisy linear inverse estimation problems which encompasses under a single framework a whole class of estimation methods. Under this framework, the prior information about the unknown parameters (when such information exists), and constraints on the parameters can be incorporated in the statement of the problem. The method builds on the basics of the maximum entropy principle and consists of transforming the original problem into an estimation of a probability density on an appropriate space naturally associated with the statement of the problem. This estimation method is generic in the sense that it provides a framework for analyzing non-normal models, it is easy to implement and is suitable for all types of inverse problems such as small and or ill-conditioned, noisy data. First order approximation, large sample properties and convergence in distribution are developed as well. Analytical examples, statistics for model comparisons and evaluations, that are inherent to this method, are discussed and complemented with explicit examples.

Keywords:

maximun entropy method; generalized entropy estimator; information-theoretic methods; parameter estimation; inverse problems PACS Code:

02.50Ga; 02.50.Tt; 02.70.Rr; 83.85.Ns

1. Introduction

Researchers in all disciplines are often faced with small and/or ill-conditioned data. Unless much is known, or assumed, about the underlying process generating these data (the signal and the noise) these types of data lead to ill-posed noisy (inverse) problems. Traditionally, these types of problems are solved by using parametric and semi-parametric estimators such as the least squares, regularization and non-likelihood methods. In this work, we propose a semi-parametric information theoretic method for solving these problems while allowing the researcher to impose prior knowledge in a non-Bayesian way. The model developed here provides a major extension of the Generalized Maximum Entropy model of Golan, Judge and Miller [1] and provides new statistical results of estimators discussed in Gzyl and Velásquez [2].

The overall purpose of this paper is fourfold. First, we develop a generic information theoretic method for solving linear, noisy inverse problems that uses minimal distributional assumptions. This method is generic in the sense that it provides a framework for analyzing non-normal models and it allows the user to incorporate prior knowledge in a non-Bayesian way. Second, we provide detailed analytic solutions for a number of possible priors. Third, using the concentrated (unconstrained) model, we are able to compare our estimator to other estimators, such as the Least Squares, regularization and Bayesian methods. Our proposed model is easy to apply and suitable for analyzing a whole class of linear inverse problems across the natural and social sciences. Fourth, we provide the large sample properties of our estimator.

To achieve our goals, we build on the current Information-Theoretic (IT) literature that is founded on the basis of the Maximum Entropy (ME) principle (Jaynes [3,4]) and on Shannon’s [5] information measure (entropy) as well as other generalized entropy measures. To understand the relationship between the familiar linear statistical model and the approach we take here, we now briefly define our basic problem, discuss its traditional solution and provide the basic logic and related literature we use here in order to solve that problem such that our objectives are achieved.

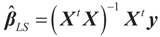

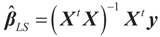

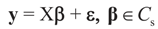

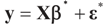

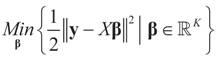

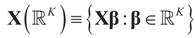

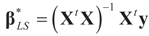

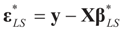

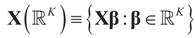

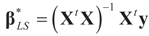

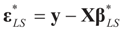

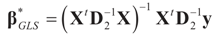

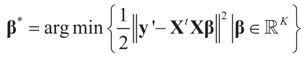

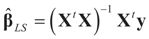

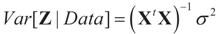

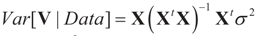

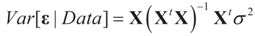

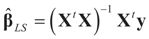

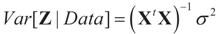

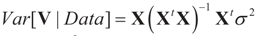

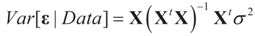

Consider the basic (linear) problem of estimating the K-dimensional location parameter vector (signal, input) β given an N-dimensional observed sample (response) vector y and an N × K design (transfer) matrix X such that y = Xβ + ε and ε is an N-dimensional random vector such that E[ε] = 0 and with some positive definite covariance matrix with a scale parameter σ2. The statistical nature of the unobserved noise term is supposed to be known, and we suppose that the second moments of the noise are finite. The researcher’s objective is to estimate the unknown vector β with minimal assumptions on ε. Recall that under the traditional regularity conditions for the linear model (and for X of rank K), the least squares, (LS), unconstrained, estimator is  and

and  where “t” stands for transpose.

where “t” stands for transpose.

and

and  where “t” stands for transpose.

where “t” stands for transpose. Consider now the problem of estimating β and ε simultaneously while imposing minimal assumptions on the likelihood structure and while incorporating certain constraints on the signal and perhaps on the noise. Further, rather than following the tradition of employing point estimators, consider estimating the empirical distribution of the unknown quantities βk and εn with the joint objectives of maximizing the in-and-out of sample prediction.

With these objectives, the problem is inherently under-determined and cannot be solved with the traditional least squares or likelihood approaches. Therefore, one must resort to a different principle. In the work done here, we follow the Maximum Entropy (ME) principle that was developed by Jaynes [3,4] for similar problems. The classical ME method consists of using a variational method to choose a probability distribution from a class of probability distributions having pre-assigned generalized moments.

In more general terms, consider the problem of estimating an unknown discrete probability distribution from a finite and possibly noisy set of observed generalized (sample) moments, that is, arbitrary functions of the data. These moments (and the fact that the distribution is proper) are supposed to be the only available information. Regardless of the level of noise in these observed moments, if the dimension of the unknown distribution is larger than the number of observed moments, there are infinitely many proper probability distributions satisfying this information. Such a problem is called an under-determined problem. Which one of the infinitely many solutions that satisfy the data should one choose? Within the class of information-theoretic (IT) methods, the chosen solution is the one that maximizes an information criterion-entropy. Procedure that we propose below to solve the estimation problem described above, fits in that framework.

We construct our proposed estimator for solving the noisy, inverse, linear problem in two basic steps. In our first step, each unknown parameter (βk and εn) is constructed as the expected value of a certain random variable. That is, we view the possible values of the unknown parameters as values of random variables whose distributions are to be determined. We will assume that the range of each such random variable contains the true unknown value of βk and εn respectively. This step actually involves two specifications. The first one is the pre-specified support space for the two sets of parameters (finite/infinite and/or bounded/unbounded). At the outset of section two we shall do this as part of the mathematical statement of the problem. Any further information we may have about the parameters is incorporated into the choice of a prior (reference) measure on these supports. Since usually a model for the noise is supposed to be known, the statistical nature of the noise is incorporated at this stage. As far as the signal goes, this is an auxiliary construction. This constitutes our second specification.

In our second step, because minimal assumptions on the likelihood implies that such a problem is under-determined, we resort to the ME principle. This means that we need to convert this under-determined problem to a well-posed, constrained optimization. Similar to the classical ME method the objective function in that constrained optimization problem is composed of N × K entropy functions: one for each one of the N × K proper probability distributions (one for each signal βk and one for each noise component εn). The constraints are just the observed information (data) and the requirement that all probability distributions are proper. Maximizing (simultaneously) the N × K entropies subject to the constraints yields the desired solution. This optimization yields a unique solution in terms of a unique set of proper probability distribution which in turn yields the desired point estimates βk and εn. Once the constrained model is solved, we construct the concentrated (unconstrained) model. In the method proposed here, we also allow introduction of different priors corresponding to one’s beliefs about the data generating process and the structure of the unknown β’s.

Our proposed estimator is a member of the IT family of estimators. The members of this family of estimators include the Empirical Likelihood (EL), the Generalized EL (GEL), the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), the Bayesian Method of Moments, (BMOM), the Generalized Maximum Entropy (GME), and the Maximum Entropy in the Mean (MEM), and are all related to the classical Maximum Entropy, ME. (e.g., Owen [6,7]; Qin and Lawless [8]; Smit, [9]; Newey and Smith [10]; Kitamura and Stutzer [11]; Imbens et al. [12]; Zellner [13,14]; Zellner and Tobias [15]; Golan, Judge and Miller [1]; Gamboa and Gassiat [16]; Gzyl [17]; Golan and Gzyl [18]). See also Gzyl and Velásquez [2], which builds upon Golan and Gzyl [18] where the synthesis was first proposed. If, in addition, the data are ill-conditioned, one often has to resort to the class of regularization methods (e.g., Hoerl and Kennard [19] O’Sullivan [20], Breiman [21], Tibshirani [22], Titterington [23], Donoho et al. [24]; Besnerais et al. [25]. A reference for regularization in statistics is Bickel and Li [26]. If some prior information on the data generation process or on the model is available, Bayesian methods are often used. For a detailed review and synthesis of the IT family of estimators, historical perspective and synthesis, see Golan [27]. For other background and related entropy and IT methods of estimation see the special volume of Advances in Econometrics (Fomby and Hill [28]) and the two special issues of the Journal of Econometrics [29,30]. For additional mathematical background see Mynbaev [31] and Asher, Borchers and Thurber [32].

Our proposed generic IT method will provide us with an estimator for the parameters of the linear statistical model that reconciles some of the objectives achieved by each one of the above methods. Like the philosophy behind the EL, we do not assume a pre-specified likelihood, but rather recover the (natural) weight of each observation via the optimization procedure (e.g., Owen [7]; Qin and Lawless [8]). Similar to regularization methods used for ill-behaved data, we follow the GME logic and use here the pre-specified support space for each one of the unknown parameters as a form of regularization (e.g., Golan, Judge and Miller [1]). The estimated parameters must fall within that space. However, unlike the GME, our method allows for infinitely large support spaces and continuous prior distributions. Like Bayesian approaches, we do use prior information. But we use these priors in a different way—in a way consistent with the basics of information theory and in line with the Kullback–Liebler entropy discrepancy measure. In that way, we are able to combine ideas from the different methods described above that together yield an efficient and consistent IT estimator that is statistically and computationally efficient and easy to apply.

In Section 2, we lay out the basic formulation and then develop our basic model. In Section 3, we provide a detailed closed form examples of the normal priors’ case and other priors. In Section 4 we develop the basic statistical properties of our estimator including first order approximation. In Section 5, we compare our method with Least Squares, regularization and Bayesian methods, including the Bayesian Method of Moments. The comparisons are done under the normal priors. An additional set of analytical examples, providing the formulation and solution of four basic priors (bounded, unbounded and a combination of both) is developed in Section 6. In Section 7, we comment on model comparison. We provide detailed closed form formulations for that section in an Appendix. We conclude in Section 8. The Appendices provide the proofs and detailed analytical formulations.

2. Problem Statement and Solution

2.1. Notation and Problem Statement

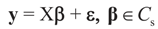

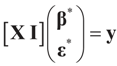

Consider the linear statistical model

where

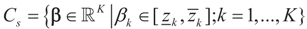

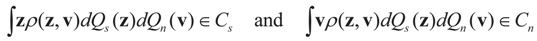

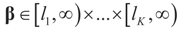

where  is an unknown K-dimensional signal vector that cannot be directly measured but is required to satisfy some convex constraints expressed as

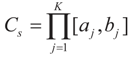

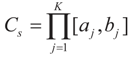

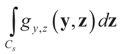

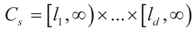

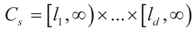

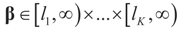

is an unknown K-dimensional signal vector that cannot be directly measured but is required to satisfy some convex constraints expressed as  where Cs is a closed convex set. For example,

where Cs is a closed convex set. For example,  with constants

with constants  . (These constraints may come from constraints on

. (These constraints may come from constraints on  , and may have a natural reason for being imposed). X is an N × K known linear operator (design matrix) that can be either fixed or stochastic,

, and may have a natural reason for being imposed). X is an N × K known linear operator (design matrix) that can be either fixed or stochastic,  is a vector of noisy observations, and

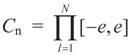

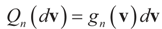

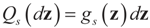

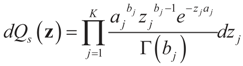

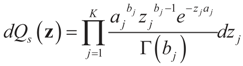

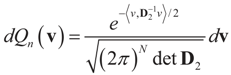

is a vector of noisy observations, and  is a noise vector. Throughout this paper we assume that the components of the noise vector ε are i.i.d. random variables with zero mean and a variance σ2 with respect to a probability law dQn(v) on

is a noise vector. Throughout this paper we assume that the components of the noise vector ε are i.i.d. random variables with zero mean and a variance σ2 with respect to a probability law dQn(v) on  We denote by Qs and Qn the prior probability measures reflecting our knowledge about β and ε respectively.

We denote by Qs and Qn the prior probability measures reflecting our knowledge about β and ε respectively.

is an unknown K-dimensional signal vector that cannot be directly measured but is required to satisfy some convex constraints expressed as

is an unknown K-dimensional signal vector that cannot be directly measured but is required to satisfy some convex constraints expressed as  where Cs is a closed convex set. For example,

where Cs is a closed convex set. For example,  with constants

with constants  . (These constraints may come from constraints on

. (These constraints may come from constraints on  , and may have a natural reason for being imposed). X is an N × K known linear operator (design matrix) that can be either fixed or stochastic,

, and may have a natural reason for being imposed). X is an N × K known linear operator (design matrix) that can be either fixed or stochastic,  is a vector of noisy observations, and

is a vector of noisy observations, and  is a noise vector. Throughout this paper we assume that the components of the noise vector ε are i.i.d. random variables with zero mean and a variance σ2 with respect to a probability law dQn(v) on

is a noise vector. Throughout this paper we assume that the components of the noise vector ε are i.i.d. random variables with zero mean and a variance σ2 with respect to a probability law dQn(v) on  We denote by Qs and Qn the prior probability measures reflecting our knowledge about β and ε respectively.

We denote by Qs and Qn the prior probability measures reflecting our knowledge about β and ε respectively. Given the indirect noisy observations y, our objective is to simultaneously recover  and the residuals

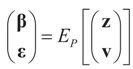

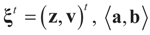

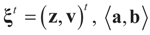

and the residuals  so that Equation (1) holds. For that, we convert problem (1) into a generalized moment problem and consider the estimated β and ε as expected values of random variables z and v with respect to an unknown probability law P. Note that z is an auxiliary random variable whereas v is the actual model for the noise perturbing the measurements. Formally:

so that Equation (1) holds. For that, we convert problem (1) into a generalized moment problem and consider the estimated β and ε as expected values of random variables z and v with respect to an unknown probability law P. Note that z is an auxiliary random variable whereas v is the actual model for the noise perturbing the measurements. Formally:

and the residuals

and the residuals  so that Equation (1) holds. For that, we convert problem (1) into a generalized moment problem and consider the estimated β and ε as expected values of random variables z and v with respect to an unknown probability law P. Note that z is an auxiliary random variable whereas v is the actual model for the noise perturbing the measurements. Formally:

so that Equation (1) holds. For that, we convert problem (1) into a generalized moment problem and consider the estimated β and ε as expected values of random variables z and v with respect to an unknown probability law P. Note that z is an auxiliary random variable whereas v is the actual model for the noise perturbing the measurements. Formally:Assumption 2.1.

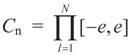

The range of z is the constraint set Cs embodying the constraints that the unknown β is to satisfy. Similarly, we assume that the range of v is a closed convex set Cn where “s” and “n” stand for signal and noise respectively. Unless otherwise specified, and in line with tradition, it is assumed that v is symmetric about zero.

Comment.

It is reasonable to assume that Cn is convex and symmetric in  . Further, in some cases the researcher may know the statistical model of the noise. In that case, this model should be used. As stated earlier, Qs and Qn are the prior probability measures for β and ε respectively. To ensure that the expected values of z and v fall in C = Cs × Cn we need the following assumption.

. Further, in some cases the researcher may know the statistical model of the noise. In that case, this model should be used. As stated earlier, Qs and Qn are the prior probability measures for β and ε respectively. To ensure that the expected values of z and v fall in C = Cs × Cn we need the following assumption.

. Further, in some cases the researcher may know the statistical model of the noise. In that case, this model should be used. As stated earlier, Qs and Qn are the prior probability measures for β and ε respectively. To ensure that the expected values of z and v fall in C = Cs × Cn we need the following assumption.

. Further, in some cases the researcher may know the statistical model of the noise. In that case, this model should be used. As stated earlier, Qs and Qn are the prior probability measures for β and ε respectively. To ensure that the expected values of z and v fall in C = Cs × Cn we need the following assumption.Assumption 2.2.

The closures of the convex hulls of the supports of Qs and Qn are respectively Cs and Cn and we set dQ = dQs × dQn.

Comment.

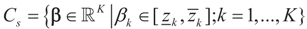

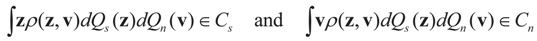

This assumption implies that for any strictly positive density ρ(z,v) we have:

To solve problems like (1) with minimal assumptions one has to (i) incorporate some prior knowledge, or constraints, on the solution, or (ii) specify a certain criterion to choose among the infinitely many solutions, or (iii) use both approaches. The different criteria used within the IT methods are all directly related to the Shannon’s information (entropy) criterion (Golan [33]). The criterion used in the method developed and discussed here is the Shannon’s entropy. For a detailed discussion and further background see for example the two special issues of the Journal of Econometrics [29,30].

2.2. The Solution

In what follows we explain how to transform the original linear problem into a generalized moment problem, or how to transform any constrained linear model like (1) into a problem consisting of finding an unknown density.

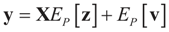

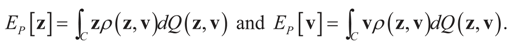

Instead of searching directly for the point estimates (β, ε)t we view it as the expected value of auxiliary random variables (z, v)t that take values in the convex set Cs×Cn distributed according to some unknown auxiliary probability law dP(z, v). Thus:

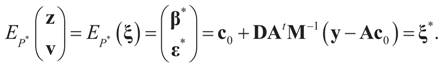

where EP denotes the expected value with respect to P.

where EP denotes the expected value with respect to P.

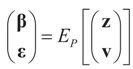

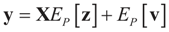

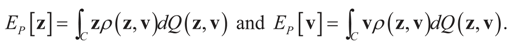

To obtain P, we introduce the reference measure dQ(z, v) = dQs(z) dQn(v) on the Borel subsets of the product space C = Cs × Cn Again, note that while C is binding, Qs describes one’s own belief/knowledge on the unknown β, whereas Qn describes the actual model for ε. With the above specification, problem (1) becomes:

Problem (1) restated:

We search for a density ρ(z, v) such that dP = ρdQ is a probability law on C and the linear relations:

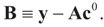

are satisfied, where:

are satisfied, where:

Under this construction,  is a random estimator of the unknown parameter vector β and

is a random estimator of the unknown parameter vector β and  is an estimator of the noise.

is an estimator of the noise.

is a random estimator of the unknown parameter vector β and

is a random estimator of the unknown parameter vector β and  is an estimator of the noise.

is an estimator of the noise.Comment.

Using dQ(z, v) = dQs(z) dQn(v) amounts to assuming an a priori independence of signal and noise. This is a natural assumption as the signal part is a mathematical artifact and the noise part is the actual model of the randomness/noise.

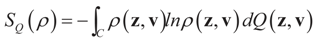

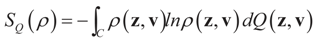

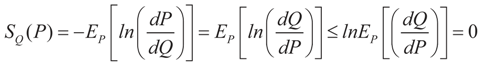

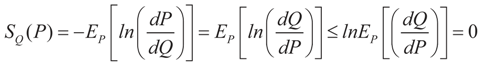

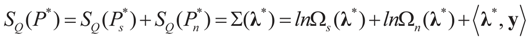

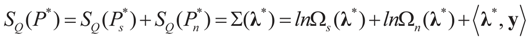

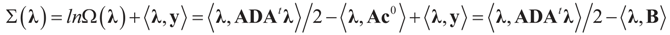

There are potentially many candidates ρ's that satisfy (3). To find one (the least informative one given the data), we set up the following variational problem: Find ρ*(z, v) that maximizes the entropy functional, SQ (ρ) defined by:

on the following admissible class of densities:

where “ln” stands for the natural logarithm. As usual we extend xlnx as 0 to x = 0. If the maximization problem has a solution, the estimates satisfy the constraints and Equations (1) or (3). The familiar and classical answer to the problem of finding such a ρ* is expressed in the following lemma.

on the following admissible class of densities:

where “ln” stands for the natural logarithm. As usual we extend xlnx as 0 to x = 0. If the maximization problem has a solution, the estimates satisfy the constraints and Equations (1) or (3). The familiar and classical answer to the problem of finding such a ρ* is expressed in the following lemma.

Lemma 2.1.

Assume that ρ is any positive density with respect to dQ and that lnρ is integrable with respect to dP = ρdQ, then SQ(P) < 0.

Proof.

By the concavity of the logarithm and Jensen’s inequality it is immediate to verify that:

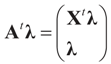

Before applying this result to our model, we define A=[X I] as an N × (K + N) matrix obtained from juxtaposing X and the N × N identity matrix I. We now work with the matrix A which allows us to consider the larger space rather than just the more traditional moment space. This is shown and discussed explicitly in the examples and derivations of Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6. For practical purposes, when facing a relatively small sample, the researcher may prefer working with A, rather than with the sample moments. This is because for finite sample the total information captured by using A is larger than when using the sample’s moments.

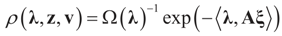

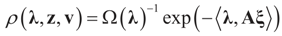

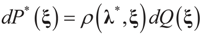

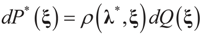

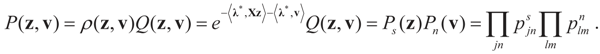

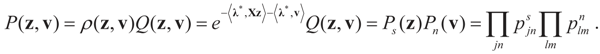

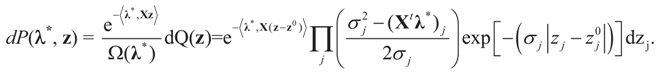

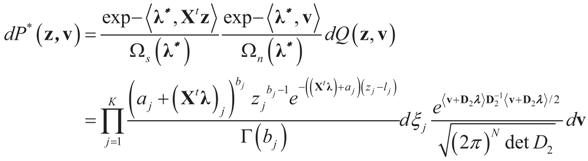

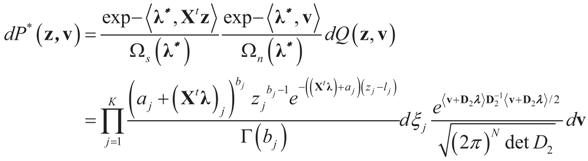

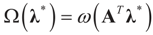

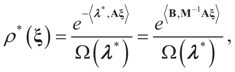

To apply lemma (1) to our model, let ρ be any member of the exponential (parametric) family:

where

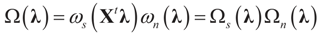

where  denotes the Euclidean scalar (inner) product of vectors a and b, and

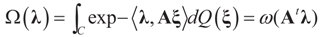

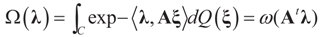

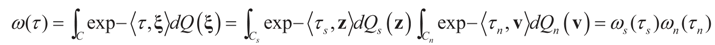

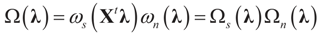

denotes the Euclidean scalar (inner) product of vectors a and b, and  are N free parameters that will play the role of Lagrange multipliers (one multiplier for each observation). The quantity Ω(λ) is the normalization function:

are N free parameters that will play the role of Lagrange multipliers (one multiplier for each observation). The quantity Ω(λ) is the normalization function:

where:

where:

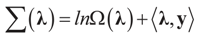

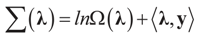

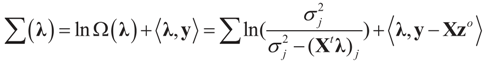

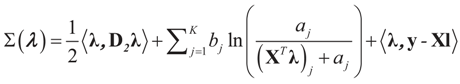

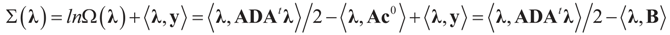

is the Laplace transform of Q. Next taking logs in (7) and defining:

is the Laplace transform of Q. Next taking logs in (7) and defining:

denotes the Euclidean scalar (inner) product of vectors a and b, and

denotes the Euclidean scalar (inner) product of vectors a and b, and  are N free parameters that will play the role of Lagrange multipliers (one multiplier for each observation). The quantity Ω(λ) is the normalization function:

are N free parameters that will play the role of Lagrange multipliers (one multiplier for each observation). The quantity Ω(λ) is the normalization function:

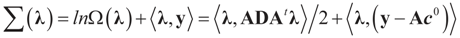

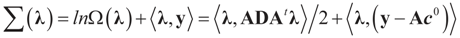

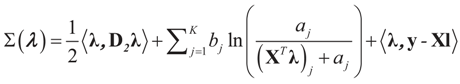

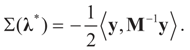

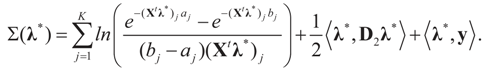

Lemma 2.1 implies that ∑(λ) ≥ SQ (ρ) for any  and for any ρ in the class of probability laws P(C) defined in (5). However, the problem is that we do not know whether the solution ρ*(λ, z, v) is a member of P(C) for some λ. Therefore, we search for λ* such that ρ* = ρ(λ*) is in P(C) and λ* is a minimum. If such a λ* is found, then we would have found a density (the unique one, for SQ is strictly convex in ρ) that maximizes the entropy, and by using the fact that β* = EP* [z] and ε* = EP* [v], the solution to (1), which is consistent with the data (3), is found. Formally, the result is contained in the following theorem. (Note that the Kullback’s measure (Kullback [34]), is a particular case of SQ(P), with a sign change and when both P and Q have densities).

and for any ρ in the class of probability laws P(C) defined in (5). However, the problem is that we do not know whether the solution ρ*(λ, z, v) is a member of P(C) for some λ. Therefore, we search for λ* such that ρ* = ρ(λ*) is in P(C) and λ* is a minimum. If such a λ* is found, then we would have found a density (the unique one, for SQ is strictly convex in ρ) that maximizes the entropy, and by using the fact that β* = EP* [z] and ε* = EP* [v], the solution to (1), which is consistent with the data (3), is found. Formally, the result is contained in the following theorem. (Note that the Kullback’s measure (Kullback [34]), is a particular case of SQ(P), with a sign change and when both P and Q have densities).

and for any ρ in the class of probability laws P(C) defined in (5). However, the problem is that we do not know whether the solution ρ*(λ, z, v) is a member of P(C) for some λ. Therefore, we search for λ* such that ρ* = ρ(λ*) is in P(C) and λ* is a minimum. If such a λ* is found, then we would have found a density (the unique one, for SQ is strictly convex in ρ) that maximizes the entropy, and by using the fact that β* = EP* [z] and ε* = EP* [v], the solution to (1), which is consistent with the data (3), is found. Formally, the result is contained in the following theorem. (Note that the Kullback’s measure (Kullback [34]), is a particular case of SQ(P), with a sign change and when both P and Q have densities).

and for any ρ in the class of probability laws P(C) defined in (5). However, the problem is that we do not know whether the solution ρ*(λ, z, v) is a member of P(C) for some λ. Therefore, we search for λ* such that ρ* = ρ(λ*) is in P(C) and λ* is a minimum. If such a λ* is found, then we would have found a density (the unique one, for SQ is strictly convex in ρ) that maximizes the entropy, and by using the fact that β* = EP* [z] and ε* = EP* [v], the solution to (1), which is consistent with the data (3), is found. Formally, the result is contained in the following theorem. (Note that the Kullback’s measure (Kullback [34]), is a particular case of SQ(P), with a sign change and when both P and Q have densities).Theorem 2.1.

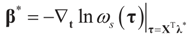

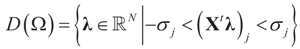

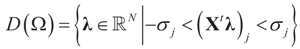

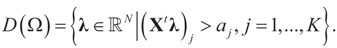

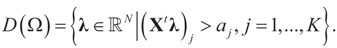

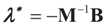

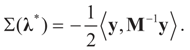

Assume that  has a non-empty interior and that the minimum of the (convex) function ∑(λ) is achieved at λ*. Then,

has a non-empty interior and that the minimum of the (convex) function ∑(λ) is achieved at λ*. Then,  satisfies the set of constrains (3) or (1) and maximizes the entropy.

satisfies the set of constrains (3) or (1) and maximizes the entropy.

has a non-empty interior and that the minimum of the (convex) function ∑(λ) is achieved at λ*. Then,

has a non-empty interior and that the minimum of the (convex) function ∑(λ) is achieved at λ*. Then,  satisfies the set of constrains (3) or (1) and maximizes the entropy.

satisfies the set of constrains (3) or (1) and maximizes the entropy.Proof.

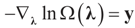

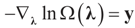

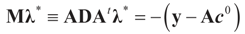

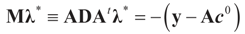

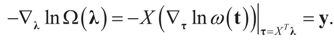

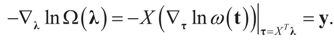

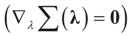

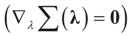

Consider the gradient of ∑(λ) at λ*. The equation to be solved to determine λ* is  which coincides with Equation (3) when the gradient is written out explicitly.

which coincides with Equation (3) when the gradient is written out explicitly.

which coincides with Equation (3) when the gradient is written out explicitly.

which coincides with Equation (3) when the gradient is written out explicitly.Note that this is equivalent to minimizing (9) which is the concentrated likelihood-entropy function. Notice as well that ∑(λ*) = SQ(ρ*)

Comment.

This theorem is practically equivalent to representing the estimator in terms of the estimating equations. Estimation equations (or functions) are the underlying equations from which the roots or solutions are derived. The logic for using these equations is (i) they have simpler form (e.g., a linear form for the LS estimator) than their roots, and (ii) they preserve the sampling properties of their roots (Durbin, [35]). To see the direct relationship between estimation equations and the dual/concentrated model (extremum estimator), note that the estimation equations are the first order conditions of the respective extremum problem. The choice of estimation equations is appropriate whenever the first order conditions characterize the global solution to the (extremum) optimization problem, which is the case in the model discussed here.

Theorem 2.1 can be summarized as follows: in order to determine β and ε from (1), it is easier to transform the algebraic problem into the problem of obtaining a minimum of the convex function ∑(λ) and then use β* = EP* [z] and ε* = EP* [v] to compute the estimates β* and ε*. The above procedure is designed in such a way that  is automatically satisfied. Since the actual measurement noise is unknown, it is treated as a quantity to be determined, and treated (mathematically) as if both β and ε were unknown. The interpretations of the reconstructed residual ε* and the reconstructed β*, are different. The latter is the unknown parameter vector we are after while the former is the residual (reconstructed error) such that the linear Equation (1),

is automatically satisfied. Since the actual measurement noise is unknown, it is treated as a quantity to be determined, and treated (mathematically) as if both β and ε were unknown. The interpretations of the reconstructed residual ε* and the reconstructed β*, are different. The latter is the unknown parameter vector we are after while the former is the residual (reconstructed error) such that the linear Equation (1),  , is satisfied. With that background, we now discuss the basic properties of our model. For a detailed comparison of a large number of IT estimation methods see Golan ([27,28,29,30,31,32,33]) and the nice text of Mittelhammer, Judge and Miller [36]

, is satisfied. With that background, we now discuss the basic properties of our model. For a detailed comparison of a large number of IT estimation methods see Golan ([27,28,29,30,31,32,33]) and the nice text of Mittelhammer, Judge and Miller [36]

is automatically satisfied. Since the actual measurement noise is unknown, it is treated as a quantity to be determined, and treated (mathematically) as if both β and ε were unknown. The interpretations of the reconstructed residual ε* and the reconstructed β*, are different. The latter is the unknown parameter vector we are after while the former is the residual (reconstructed error) such that the linear Equation (1),

is automatically satisfied. Since the actual measurement noise is unknown, it is treated as a quantity to be determined, and treated (mathematically) as if both β and ε were unknown. The interpretations of the reconstructed residual ε* and the reconstructed β*, are different. The latter is the unknown parameter vector we are after while the former is the residual (reconstructed error) such that the linear Equation (1),  , is satisfied. With that background, we now discuss the basic properties of our model. For a detailed comparison of a large number of IT estimation methods see Golan ([27,28,29,30,31,32,33]) and the nice text of Mittelhammer, Judge and Miller [36]

, is satisfied. With that background, we now discuss the basic properties of our model. For a detailed comparison of a large number of IT estimation methods see Golan ([27,28,29,30,31,32,33]) and the nice text of Mittelhammer, Judge and Miller [36] 3. Closed Form Examples

With the above formulation, we now turn to a number of relatively simple analytical examples. These examples demonstrate the advantages of our method and its simplicity. In Section 6 we provide additional closed form examples.

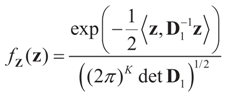

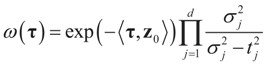

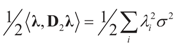

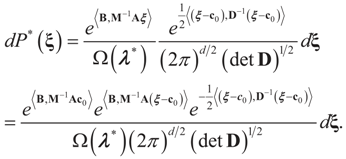

3.1. Normal Priors

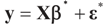

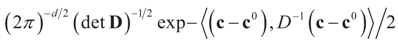

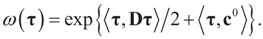

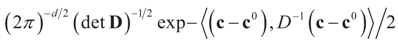

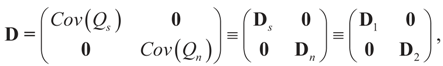

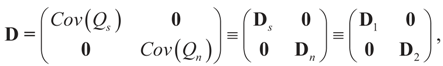

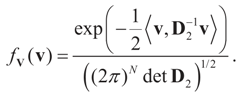

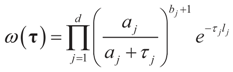

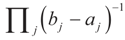

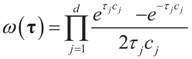

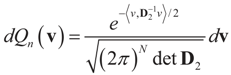

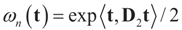

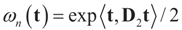

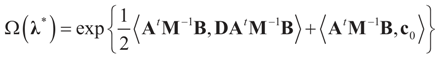

In this example the index d takes the possible values (dimensions) K, N, or K+N depending if it relates to Cs (or z), to Cn (or v) or to both. Assume the reference prior dQ is a normal random vector with d × d [i.e., K × K, N × N or (N + K) × (N + K)] covariance matrix D, the law of which has density  where

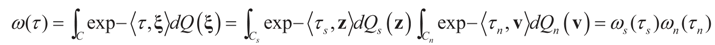

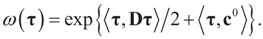

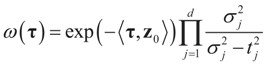

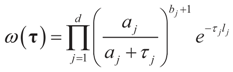

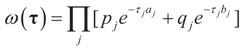

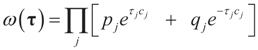

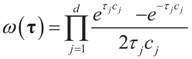

where  is the vector of prior means and is specified by the researcher. Next, we define the Laplace transform, ω(τ), of the normal prior. This transform involves the diagonal covariance matrix for the noise and signal models:

is the vector of prior means and is specified by the researcher. Next, we define the Laplace transform, ω(τ), of the normal prior. This transform involves the diagonal covariance matrix for the noise and signal models:

where

where  is the vector of prior means and is specified by the researcher. Next, we define the Laplace transform, ω(τ), of the normal prior. This transform involves the diagonal covariance matrix for the noise and signal models:

is the vector of prior means and is specified by the researcher. Next, we define the Laplace transform, ω(τ), of the normal prior. This transform involves the diagonal covariance matrix for the noise and signal models:

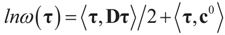

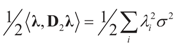

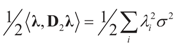

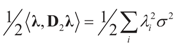

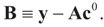

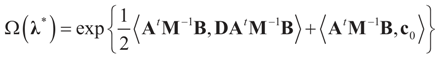

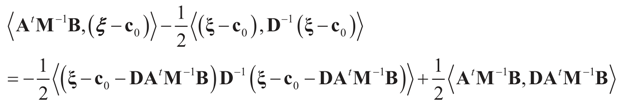

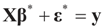

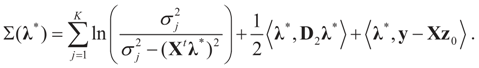

Since  then replacing τ by either Xtλ or by λ, (for the noise vector) verifies that Ω(λ) turns out to be of a quadratic form, and therefore the problem of minimizing ∑(λ) is just a quadratic minimization problem. In this case, no bounds are specified on the parameters. Instead, normal priors are used.

then replacing τ by either Xtλ or by λ, (for the noise vector) verifies that Ω(λ) turns out to be of a quadratic form, and therefore the problem of minimizing ∑(λ) is just a quadratic minimization problem. In this case, no bounds are specified on the parameters. Instead, normal priors are used.

then replacing τ by either Xtλ or by λ, (for the noise vector) verifies that Ω(λ) turns out to be of a quadratic form, and therefore the problem of minimizing ∑(λ) is just a quadratic minimization problem. In this case, no bounds are specified on the parameters. Instead, normal priors are used.

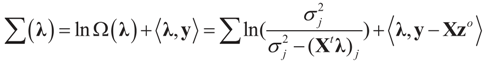

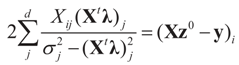

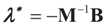

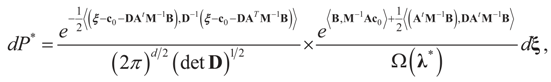

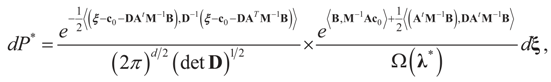

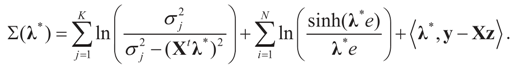

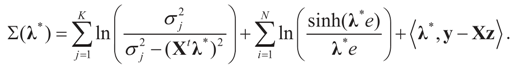

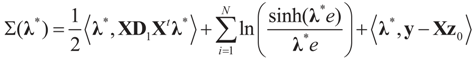

then replacing τ by either Xtλ or by λ, (for the noise vector) verifies that Ω(λ) turns out to be of a quadratic form, and therefore the problem of minimizing ∑(λ) is just a quadratic minimization problem. In this case, no bounds are specified on the parameters. Instead, normal priors are used. From (10) we get the concentrated model:

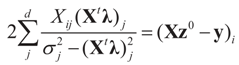

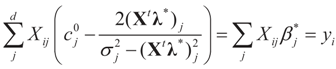

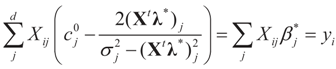

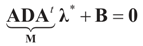

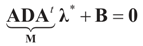

with a minimum at λ*, satisfying:

with a minimum at λ*, satisfying:

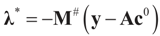

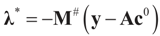

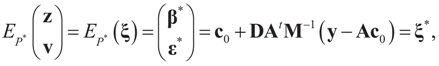

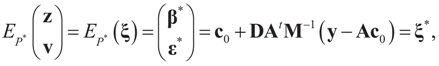

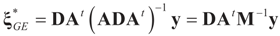

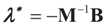

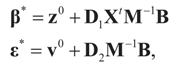

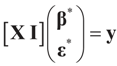

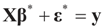

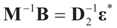

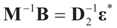

If M# denotes the generalized inverse of M = ADAt then  and therefore:

and therefore:

and therefore:

and therefore:

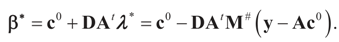

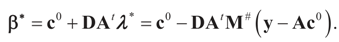

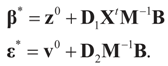

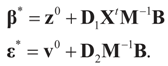

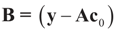

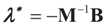

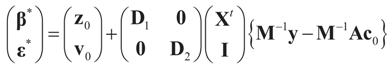

For the general case A = [X I] and:

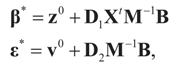

the generalized entropy solution for the traditional linear model is:

the generalized entropy solution for the traditional linear model is:

so:

so:

and finally:

and finally:

Here  . See Appendix 2 for a detailed derivation.

. See Appendix 2 for a detailed derivation.

. See Appendix 2 for a detailed derivation.

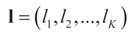

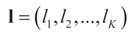

. See Appendix 2 for a detailed derivation.3.2. Discrete Uniform Priors — A GME Model

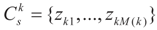

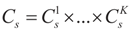

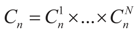

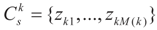

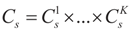

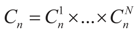

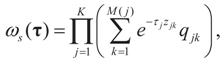

Consider now the uniform priors, which is basically the GME method (Golan, Judge and Miller [1]). Jaynes’s classical ME estimator (Jaynes [3,4]) is a special case of the GME. Let the components of z take discrete values, and let  for 1 ≤ k ≤ K Note that we allow for the cardinality of each of these sets to vary. Next, define

for 1 ≤ k ≤ K Note that we allow for the cardinality of each of these sets to vary. Next, define  . A similar construction may be proposed for the noise terms, namely we put

. A similar construction may be proposed for the noise terms, namely we put  . Since the spaces are discrete, the information is described by the obvious σ-algebras and both the prior and post-data measures will be discrete. As a prior on the signal space, we may consider:

. Since the spaces are discrete, the information is described by the obvious σ-algebras and both the prior and post-data measures will be discrete. As a prior on the signal space, we may consider:

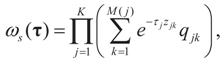

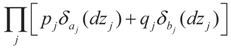

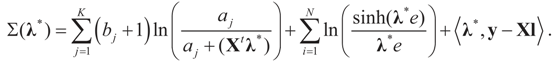

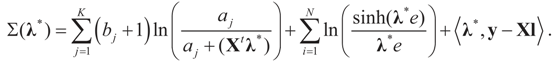

where a similar expression may be specified for the priors on Cn. Finally, we get:

where a similar expression may be specified for the priors on Cn. Finally, we get:

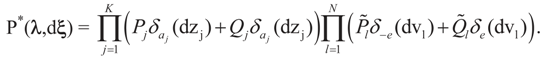

together with a similar expression for the Laplace transform of the noise prior. Notice that since the noise and signal are independent in the priors, this is also true for the post-data, so:

together with a similar expression for the Laplace transform of the noise prior. Notice that since the noise and signal are independent in the priors, this is also true for the post-data, so:

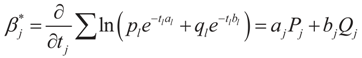

Finally,

Finally,  and

and  . For detailed derivations and discussion of the GME see Golan, Judge and Miller [1].

. For detailed derivations and discussion of the GME see Golan, Judge and Miller [1].

for 1 ≤ k ≤ K Note that we allow for the cardinality of each of these sets to vary. Next, define

for 1 ≤ k ≤ K Note that we allow for the cardinality of each of these sets to vary. Next, define  . A similar construction may be proposed for the noise terms, namely we put

. A similar construction may be proposed for the noise terms, namely we put  . Since the spaces are discrete, the information is described by the obvious σ-algebras and both the prior and post-data measures will be discrete. As a prior on the signal space, we may consider:

. Since the spaces are discrete, the information is described by the obvious σ-algebras and both the prior and post-data measures will be discrete. As a prior on the signal space, we may consider:

and

and  . For detailed derivations and discussion of the GME see Golan, Judge and Miller [1].

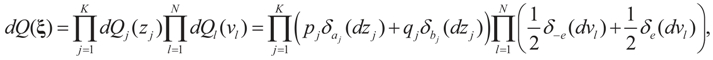

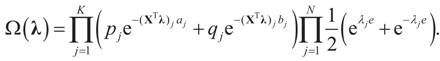

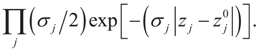

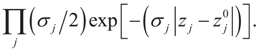

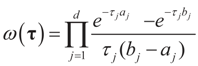

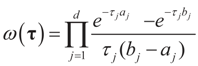

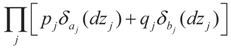

. For detailed derivations and discussion of the GME see Golan, Judge and Miller [1]. 3.3. Signal and Noise Bounded Above and Below

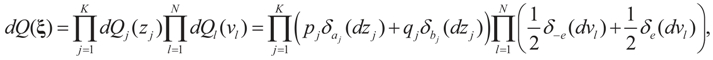

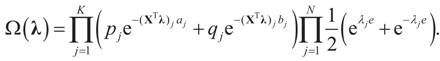

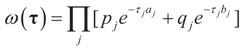

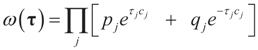

Consider the case in which both β and ε are bounded above and below. This time we place a Bernoulli measure on the constraint space Cs and the noise space Cn. Let  and

and  for the signal and noise bounds aj, bj and e respectively. The Bernoulli a priori measure on C = Cs × Cn is:

for the signal and noise bounds aj, bj and e respectively. The Bernoulli a priori measure on C = Cs × Cn is:

where δc (dz) denotes the (Dirac) unit point mass at some point c. Recalling that A = [X ,I] we now compute the Laplace transform ω(t) of Q, which in turn yields Ω(λ)=ω(ATλ):

where δc (dz) denotes the (Dirac) unit point mass at some point c. Recalling that A = [X ,I] we now compute the Laplace transform ω(t) of Q, which in turn yields Ω(λ)=ω(ATλ):

and

and  for the signal and noise bounds aj, bj and e respectively. The Bernoulli a priori measure on C = Cs × Cn is:

for the signal and noise bounds aj, bj and e respectively. The Bernoulli a priori measure on C = Cs × Cn is:

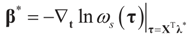

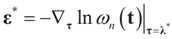

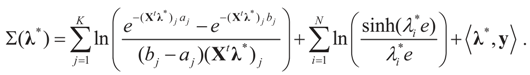

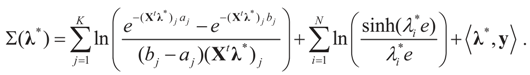

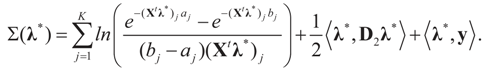

The concentrated entropy function is:

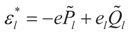

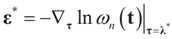

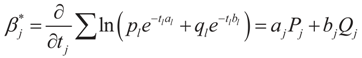

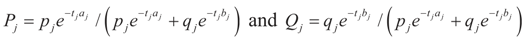

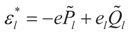

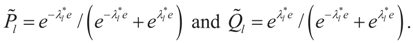

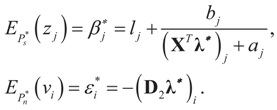

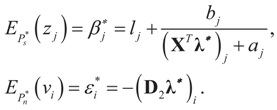

The minimizer of this function is the Lagrange multiplier vector λ*. Once it has been found, then  and

and  . Explicitly:

. Explicitly:

where:

where:

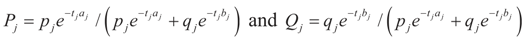

and τ = (XTλ*). Similarly:

and τ = (XTλ*). Similarly:

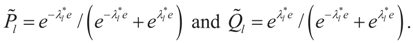

where:

where:

and

and  . Explicitly:

. Explicitly:

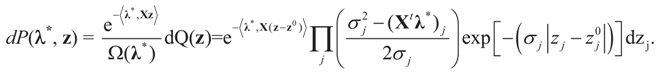

These are respectively the Maximum Entropy probabilities that the auxiliary random variables zj will attain the values aj or bj, or the auxiliary random variables vl describing the error terms attain the values ±e. These can be also obtained as the expected values of v and z with respect to the post-data measure P*(λ,dξ) given by:

Note that this model is the continuous version of the discrete GME model described earlier.

4. Main Results

4.1. Large Sample Properties

In this section we develop the basic statistical results. In order to develop these results for our generic IT estimator, we needed to employ tools that are different than the standard tools used for developing asymptotic theories (e.g., Mynbaev [31] or in Mittelhammer et al. [36]).

4.1.1. Notations and First Order Approximation

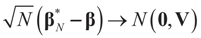

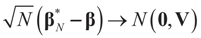

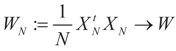

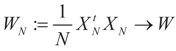

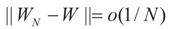

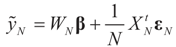

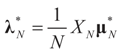

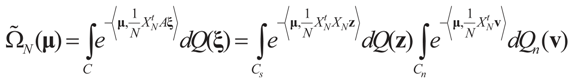

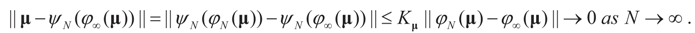

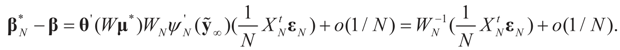

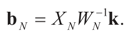

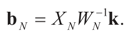

Denote by  the estimator of the true β when the sample size is N. Throughout this section we add a subscript N to all quantities introduced in Section 2 to remind us that the size of the data set is N. We want to show that

the estimator of the true β when the sample size is N. Throughout this section we add a subscript N to all quantities introduced in Section 2 to remind us that the size of the data set is N. We want to show that  and

and  as N → ∞ in some appropriate way (for some covariance V). We state here the basic notations, assumptions and results and leave the details to the Appendix. The problem is that when N varies, we are dealing with problems of different sizes (recall λ is of dimension N in our generic model). To turn all problems to the same size let:

as N → ∞ in some appropriate way (for some covariance V). We state here the basic notations, assumptions and results and leave the details to the Appendix. The problem is that when N varies, we are dealing with problems of different sizes (recall λ is of dimension N in our generic model). To turn all problems to the same size let:

the estimator of the true β when the sample size is N. Throughout this section we add a subscript N to all quantities introduced in Section 2 to remind us that the size of the data set is N. We want to show that

the estimator of the true β when the sample size is N. Throughout this section we add a subscript N to all quantities introduced in Section 2 to remind us that the size of the data set is N. We want to show that  and

and  as N → ∞ in some appropriate way (for some covariance V). We state here the basic notations, assumptions and results and leave the details to the Appendix. The problem is that when N varies, we are dealing with problems of different sizes (recall λ is of dimension N in our generic model). To turn all problems to the same size let:

as N → ∞ in some appropriate way (for some covariance V). We state here the basic notations, assumptions and results and leave the details to the Appendix. The problem is that when N varies, we are dealing with problems of different sizes (recall λ is of dimension N in our generic model). To turn all problems to the same size let:

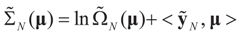

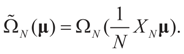

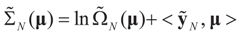

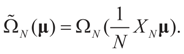

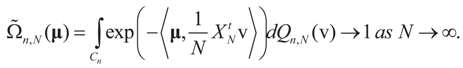

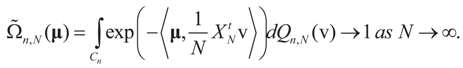

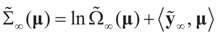

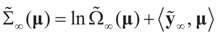

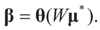

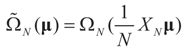

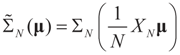

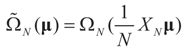

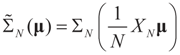

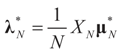

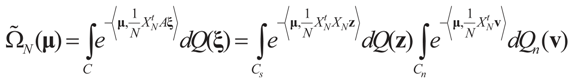

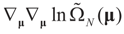

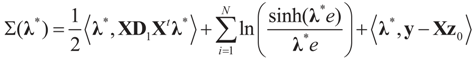

The modified data vector and the modified error terms are K-dimensional (moment) vectors, and the modified design matrix is a K×K-matrix. Problem (15), call it the moment, or the stochastic moment, problem, can be solved using the above generic IT approach which reduces to minimizing the modified concentrated (dual) entropy function:

where

where  .and

.and

.and

.and

Assumption 4.1.

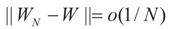

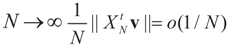

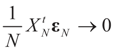

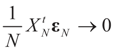

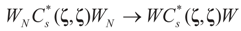

Assume that there exits an invertible K × K symmetric and positive definite matrix W such that  More precisely, assume that

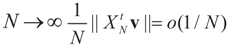

More precisely, assume that  as N → ∞. Assume as well that for any N-vector v, as

as N → ∞. Assume as well that for any N-vector v, as  .

.

More precisely, assume that

More precisely, assume that  as N → ∞. Assume as well that for any N-vector v, as

as N → ∞. Assume as well that for any N-vector v, as  .

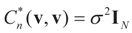

. Recall that in finite dimensions all norms are equivalent so convergence in any norm is equivalent to component wise convergence. This implies that under Assumption 4.1, the vectors  converge to 0 in L2, therefore in probability. To see the logic for that statement, recall that the vector εN has covariance matrix σ2IN. Therefore,

converge to 0 in L2, therefore in probability. To see the logic for that statement, recall that the vector εN has covariance matrix σ2IN. Therefore,  and assumption 4.1 yields the above conclusion. (To keep notations simple, and without loss of generality, we discuss here the case of σ2IN.)

and assumption 4.1 yields the above conclusion. (To keep notations simple, and without loss of generality, we discuss here the case of σ2IN.)

converge to 0 in L2, therefore in probability. To see the logic for that statement, recall that the vector εN has covariance matrix σ2IN. Therefore,

converge to 0 in L2, therefore in probability. To see the logic for that statement, recall that the vector εN has covariance matrix σ2IN. Therefore,  and assumption 4.1 yields the above conclusion. (To keep notations simple, and without loss of generality, we discuss here the case of σ2IN.)

and assumption 4.1 yields the above conclusion. (To keep notations simple, and without loss of generality, we discuss here the case of σ2IN.)Corollary 4.1.

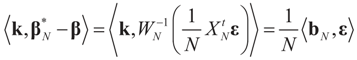

By Equation (15)  . Let

. Let  where β is the true but unknown vector of parameters. Then,

where β is the true but unknown vector of parameters. Then,  as N → ∞ (the proof is immediate).

as N → ∞ (the proof is immediate).

. Let

. Let  where β is the true but unknown vector of parameters. Then,

where β is the true but unknown vector of parameters. Then,  as N → ∞ (the proof is immediate).

as N → ∞ (the proof is immediate).Lemma 4.1.

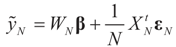

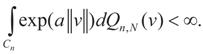

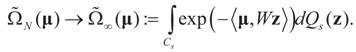

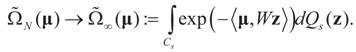

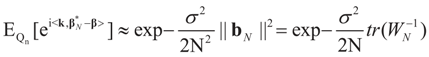

Under Assumption 4.1 and assume that for real a  Then, for

Then, for  ,

,  as N → ∞. Equivalently,

as N → ∞. Equivalently,  as N → ∞ weakly in

as N → ∞ weakly in  with respect to the appropriate induced measure.

with respect to the appropriate induced measure.

Then, for

Then, for  ,

,  as N → ∞. Equivalently,

as N → ∞. Equivalently,  as N → ∞ weakly in

as N → ∞ weakly in  with respect to the appropriate induced measure.

with respect to the appropriate induced measure.Proof of lemma 4.1.

Note that for  :

:

:

:

This is equivalent to the assertion of the lemma.

Lemma 4.2.

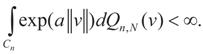

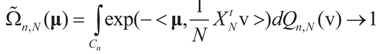

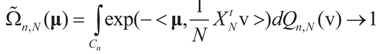

Let  Then, under Assumption 4.1:

Then, under Assumption 4.1:

Then, under Assumption 4.1:

Then, under Assumption 4.1:

Comment.

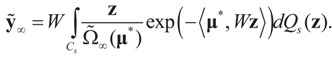

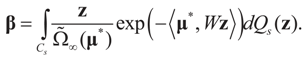

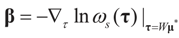

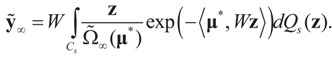

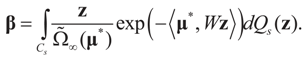

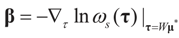

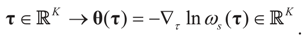

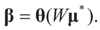

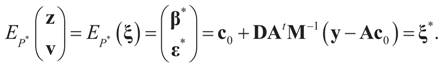

Observe that the μ* that minimizes  satisfies:

satisfies:  Or since W is invertible, β admits the representation

Or since W is invertible, β admits the representation  Note that this last identity can be written as

Note that this last identity can be written as

satisfies:

satisfies:  Or since W is invertible, β admits the representation

Or since W is invertible, β admits the representation  Note that this last identity can be written as

Note that this last identity can be written as

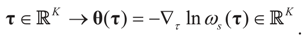

Next, we define the function:

Assumption 4.2.

The function θ(τ) is invertible and continuously differentiable.

Observe that we also have  To relate the solution to problem (1) to that of problem (15), observe that

To relate the solution to problem (1) to that of problem (15), observe that  as well as

as well as  where ΩN and ∑N are the functions introduced in Section 2 for a problem of size N. To relate the solution of the problem of size K to that of the problem of size N, we have:

where ΩN and ∑N are the functions introduced in Section 2 for a problem of size N. To relate the solution of the problem of size K to that of the problem of size N, we have:

To relate the solution to problem (1) to that of problem (15), observe that

To relate the solution to problem (1) to that of problem (15), observe that  as well as

as well as  where ΩN and ∑N are the functions introduced in Section 2 for a problem of size N. To relate the solution of the problem of size K to that of the problem of size N, we have:

where ΩN and ∑N are the functions introduced in Section 2 for a problem of size N. To relate the solution of the problem of size K to that of the problem of size N, we have:Lemma 4.3.

If  denotes the minimizer of

denotes the minimizer of  then

then  is the minimizer of ∑N(λ).

is the minimizer of ∑N(λ).

denotes the minimizer of

denotes the minimizer of  then

then  is the minimizer of ∑N(λ).

is the minimizer of ∑N(λ).Proof of Lemma 4.3.

Recall that:

From this, the desired result follows after a simple computation.

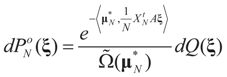

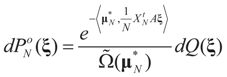

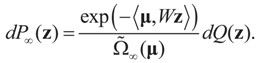

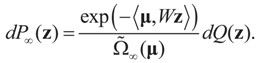

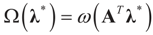

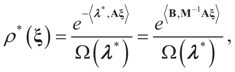

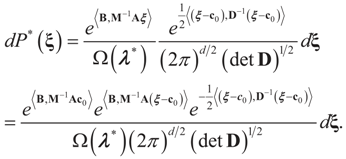

We write the post data probability that solves problem (15) (or (1)) as:

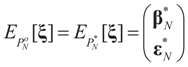

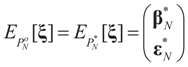

Recalling that  is the solution for the N-dimensional (data) problem and

is the solution for the N-dimensional (data) problem and  is the solution for the moment problem, we have the following result:

is the solution for the moment problem, we have the following result:

is the solution for the N-dimensional (data) problem and

is the solution for the N-dimensional (data) problem and  is the solution for the moment problem, we have the following result:

is the solution for the moment problem, we have the following result:Corollary 4.2.

With the notations introduced above and by Lemma 4.3 we have  .

.

.

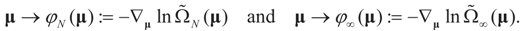

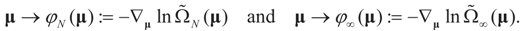

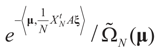

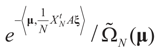

.To state Lemma 4.4 we must consider the functions  defined by:

defined by:

defined by:

defined by:

Denote by  the measure with density

the measure with density  with respect to Q. The invertibility of the functions defined above is related to the non-singularity of their Jacobian matrices, which are the

with respect to Q. The invertibility of the functions defined above is related to the non-singularity of their Jacobian matrices, which are the  -covariances of ξ. These functions will be invertible as long as these quantities are positive definite. The relationship among the above quantities is expressed in the following lemma:

-covariances of ξ. These functions will be invertible as long as these quantities are positive definite. The relationship among the above quantities is expressed in the following lemma:

the measure with density

the measure with density  with respect to Q. The invertibility of the functions defined above is related to the non-singularity of their Jacobian matrices, which are the

with respect to Q. The invertibility of the functions defined above is related to the non-singularity of their Jacobian matrices, which are the  -covariances of ξ. These functions will be invertible as long as these quantities are positive definite. The relationship among the above quantities is expressed in the following lemma:

-covariances of ξ. These functions will be invertible as long as these quantities are positive definite. The relationship among the above quantities is expressed in the following lemma:Lemma 4.4.

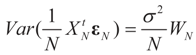

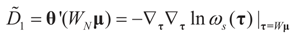

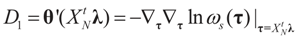

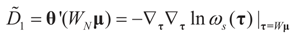

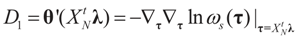

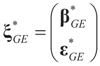

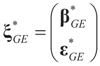

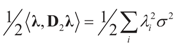

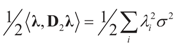

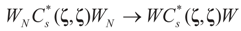

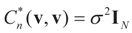

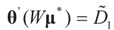

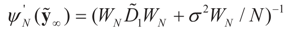

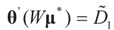

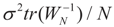

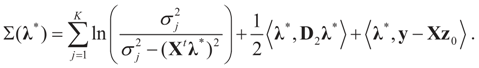

With the notations introduced above and in (8), and recall that we suppose that D2 = σ2IN we have:  and

and  where

where  ,

,  and θ' is the first derivative of θ.

and θ' is the first derivative of θ.

and

and  where

where  ,

,  and θ' is the first derivative of θ.

and θ' is the first derivative of θ.Comment.

The block structure of the covariance matrix results from the independence of the signal and the noise components in both in the prior measure dQ and the post data (maximum entropy) probability measure dP*.

Following the above, we assume:

Assumption 4.3.

The eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix  are uniformly (with respect to N and μ) bounded below away from zero.

are uniformly (with respect to N and μ) bounded below away from zero.

are uniformly (with respect to N and μ) bounded below away from zero.

are uniformly (with respect to N and μ) bounded below away from zero. Proposition 4.1.

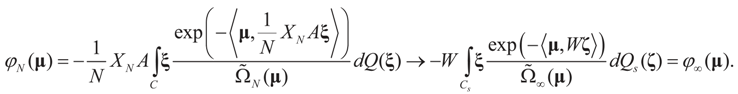

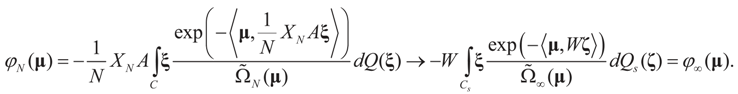

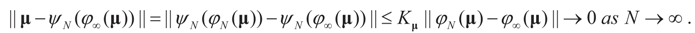

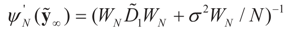

Let ψN (Y), ψ∞ (Y) respectively denote the compositional inverses of φN (μ), φ∞ (μ). Then, as N → ∞, (i) φN (μ) → φ∞ (μ) and (ii) ψN (y) → ψ∞ (y).

The proof is presented in the Appendix.

4.1.2. First Order Unbiasedness

Lemma 4.5.

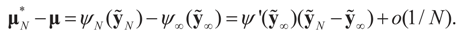

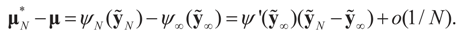

(First Order Unbiasedness). With the notations introduced above and under Assumptions 4.1–4.3, assume furthermore that  as N →∞. Then up to o(1/N),

as N →∞. Then up to o(1/N),  is an unbiased estimator of β.

is an unbiased estimator of β.

as N →∞. Then up to o(1/N),

as N →∞. Then up to o(1/N),  is an unbiased estimator of β.

is an unbiased estimator of β.The proof is presented in the Appendix.

4.1.3. Consistency

The following lemma and proposition provide results related to the large sample behavior of our generalized entropy estimator. For simplicity of the proof and without loss of generality, we suppose here that  .

.

.

.Lemma 4.6.

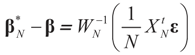

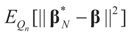

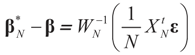

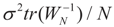

(Consistency in squared mean). Under the same assumptions of Lemma 4.5, since E[ε]=0 and the ε are homoskedastic, then  in square mean as N → ∞.

in square mean as N → ∞.

in square mean as N → ∞.

in square mean as N → ∞.Next, we provide our main result of convergence in distribution.

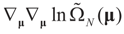

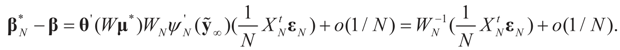

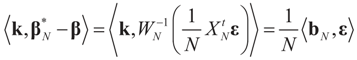

Proposition 4.2.

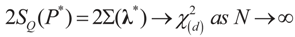

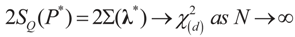

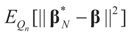

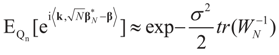

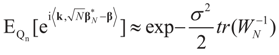

(Convergence in distribution). Under the same assumptions as in Lemma 4.5 we have

stands for convergence in distribution (or law).

stands for convergence in distribution (or law).

- (a)

as N → ∞,

as N → ∞,- (b)

as N → ∞,

as N → ∞,

stands for convergence in distribution (or law).

stands for convergence in distribution (or law).Both proofs are presented in the Appendix.

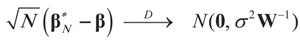

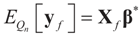

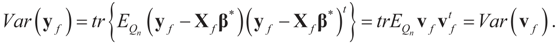

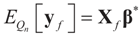

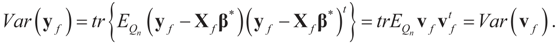

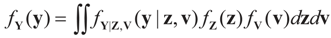

4.2. Forecasting

Once the Generalized Entropy (GE) estimated vector β* has been found, we can use it to predict future (yet) “unobserved” values. If additive noise (ε or v) is distributed according to the same prior Qn, and if future observations are determined by the design matrix Xf, then the possible future observations are described by a random variable yf given by  . For example, if vf is centered (on 0), then

. For example, if vf is centered (on 0), then  and:

and:

. For example, if vf is centered (on 0), then

. For example, if vf is centered (on 0), then  and:

and:

In the next section we contrast our estimator with other estimators. Then, in Section 6 we provide more analytic solutions for different priors.

5. Method Comparison

In this Section we contrast our IT estimator with other estimators that are often used for estimating the location vector β in the noisy, inverse linear problem. We start with the least squares (LS) model, continue with the generalized LS (GLS) and then discuss the regularization method often used for ill-posed problems. We then contrast our estimator with a Bayesian one and with the Bayesian Method of Moments (BMOM). We also show that exact correspondence between our estimator and the other estimators under normal priors.

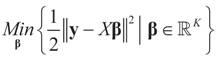

5.1. The Least Squares Methods

5.1.1. The General Case

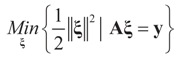

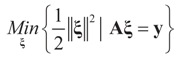

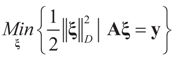

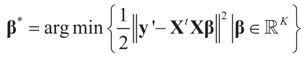

We first consider the purely geometric/algebraic approach for solving the linear model (1). A traditional method consists of solving the variational problem:

The rationale here is that because of the noise ε, the data  may fall outside the range

may fall outside the range  of X, so the objective is to minimize that discrepancy. The minimizer

of X, so the objective is to minimize that discrepancy. The minimizer  of (16) provides us with the LS estimates that minimize the errors sum of square distance from the data to

of (16) provides us with the LS estimates that minimize the errors sum of square distance from the data to  . When (XtX)− exists, then

. When (XtX)− exists, then  . The reconstruction error

. The reconstruction error  can be thought of as our estimate of the “minimal error in quadratic norm” of the measurement errors, or of the noise present in the measurements.

can be thought of as our estimate of the “minimal error in quadratic norm” of the measurement errors, or of the noise present in the measurements.

may fall outside the range

may fall outside the range  of X, so the objective is to minimize that discrepancy. The minimizer

of X, so the objective is to minimize that discrepancy. The minimizer  of (16) provides us with the LS estimates that minimize the errors sum of square distance from the data to

of (16) provides us with the LS estimates that minimize the errors sum of square distance from the data to  . When (XtX)− exists, then

. When (XtX)− exists, then  . The reconstruction error

. The reconstruction error  can be thought of as our estimate of the “minimal error in quadratic norm” of the measurement errors, or of the noise present in the measurements.

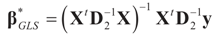

can be thought of as our estimate of the “minimal error in quadratic norm” of the measurement errors, or of the noise present in the measurements.The optimization (16) can be carried out with respect to different norms. In particular, we could have considered  . In this case we get the GLS solution

. In this case we get the GLS solution  for any general (covariance) matrix D with blocks D1 and D2.

for any general (covariance) matrix D with blocks D1 and D2.

. In this case we get the GLS solution

. In this case we get the GLS solution  for any general (covariance) matrix D with blocks D1 and D2.

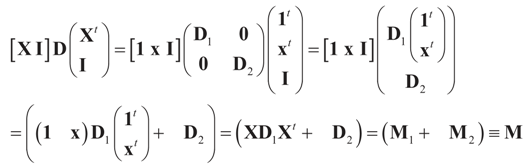

for any general (covariance) matrix D with blocks D1 and D2.If, on the other hand, our objective is to reconstruct simultaneously both the signal and the noise, we can rewrite (1) as:

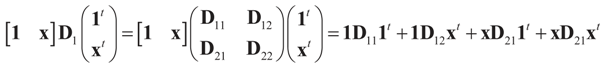

where A and ξ are as defined in Section 2. Since

where A and ξ are as defined in Section 2. Since  ,

,  and the matrix A is of dimension N × (N + K), there are infinitely many solutions that satisfy the observed data in (1) (or (17)). To choose a single solution we solve the following model:

and the matrix A is of dimension N × (N + K), there are infinitely many solutions that satisfy the observed data in (1) (or (17)). To choose a single solution we solve the following model:

,

,  and the matrix A is of dimension N × (N + K), there are infinitely many solutions that satisfy the observed data in (1) (or (17)). To choose a single solution we solve the following model:

and the matrix A is of dimension N × (N + K), there are infinitely many solutions that satisfy the observed data in (1) (or (17)). To choose a single solution we solve the following model:

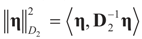

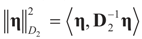

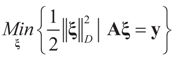

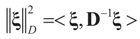

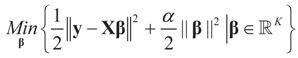

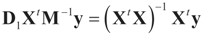

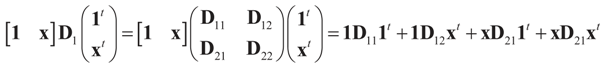

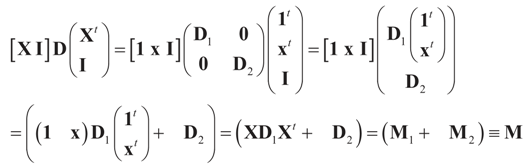

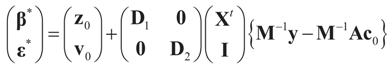

In the more general case we can incorporate the covariance matrix to weigh the different components of ξ:

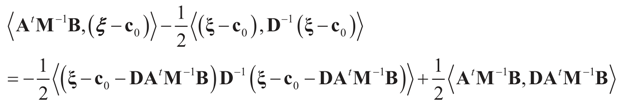

where

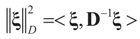

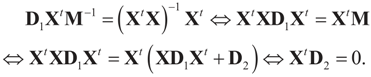

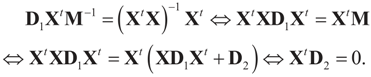

where  is a weighted norm in the extended signal-noise space (C = Cs × Cn) and D can be taken to be the full covariance matrix composed of both D1 and D2 defined in Section 3.1. Under the assumption that M ≡ (ADAt) is invertible, the solution to the variational problem (19) is given by

is a weighted norm in the extended signal-noise space (C = Cs × Cn) and D can be taken to be the full covariance matrix composed of both D1 and D2 defined in Section 3.1. Under the assumption that M ≡ (ADAt) is invertible, the solution to the variational problem (19) is given by  . This solution coincides with our Generalized Entropy formulation when normal priors are imposed and are centered about zero (c0 = 0) as is developed explicitly in Equation (14).

. This solution coincides with our Generalized Entropy formulation when normal priors are imposed and are centered about zero (c0 = 0) as is developed explicitly in Equation (14).

is a weighted norm in the extended signal-noise space (C = Cs × Cn) and D can be taken to be the full covariance matrix composed of both D1 and D2 defined in Section 3.1. Under the assumption that M ≡ (ADAt) is invertible, the solution to the variational problem (19) is given by

is a weighted norm in the extended signal-noise space (C = Cs × Cn) and D can be taken to be the full covariance matrix composed of both D1 and D2 defined in Section 3.1. Under the assumption that M ≡ (ADAt) is invertible, the solution to the variational problem (19) is given by  . This solution coincides with our Generalized Entropy formulation when normal priors are imposed and are centered about zero (c0 = 0) as is developed explicitly in Equation (14).

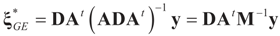

. This solution coincides with our Generalized Entropy formulation when normal priors are imposed and are centered about zero (c0 = 0) as is developed explicitly in Equation (14).If, on the other hand, the problem is ill-posed (e.g., X is not invertible), then the solution is not unique, and a combination of the above two methods (16 and 18) can be used. This yields the regularization method consisting of finding β such that:

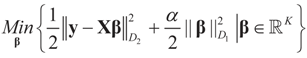

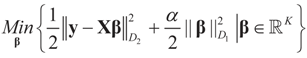

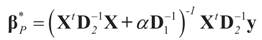

is achieved (see for example, Donoho et al. [25] for a nice discussion of regularization within the ME formulation.) Traditionally, the positive penalization parameter α is specified to favor small sized reconstructions, meaning that out of all possible reconstructions with a given discrepancy, those with the smallest norms are chosen. The norms in (20) can be chosen to be weighted, so that the model can be generalized to:

is achieved (see for example, Donoho et al. [25] for a nice discussion of regularization within the ME formulation.) Traditionally, the positive penalization parameter α is specified to favor small sized reconstructions, meaning that out of all possible reconstructions with a given discrepancy, those with the smallest norms are chosen. The norms in (20) can be chosen to be weighted, so that the model can be generalized to:

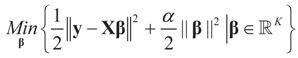

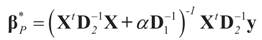

The solution is:

where D1 and D2 can be substituted for any weight matrix of interest. Using the first component of

where D1 and D2 can be substituted for any weight matrix of interest. Using the first component of  , we can state the following.

, we can state the following.

, we can state the following.

, we can state the following.Lemma 5.1.

With the above notations,  for α = 1.

for α = 1.

for α = 1.

for α = 1.Proof of Lemma 5.1.

The condition  amounts to:

amounts to:

independently of y. For this equality to hold, α=1.

independently of y. For this equality to hold, α=1.

amounts to:

amounts to:

The above result shows that if we weigh the discrepancy between the observed data (y) and its true value (Xβ) by the prior covariance matrix D2, the penalized GLS and our entropy solutions coincide for α=1 and for normal priors.

The comparison of  with

with  is stated below.

is stated below.

with

with  is stated below.

is stated below.Lemma 5.2.

With the above notations,  =

=  when the constraints are in terms of pure moments (zero moments).

when the constraints are in terms of pure moments (zero moments).

=

=  when the constraints are in terms of pure moments (zero moments).

when the constraints are in terms of pure moments (zero moments).Proof of Lemma 5.2.

If  =

=  , then

, then  for all y, which implies the following chain of identities:

for all y, which implies the following chain of identities:

=

=  , then

, then  for all y, which implies the following chain of identities:

for all y, which implies the following chain of identities:

Clearly there are only two possibilities. First, if the noise components are not constant, D2 is invertible and therefore Xt must vanish (trivial but an uninteresting case). Second, if the variance of the noise component is zero, (1) becomes a pure linear inverse problem (i.e., we solve y = Xβ).

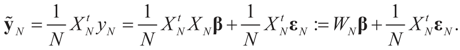

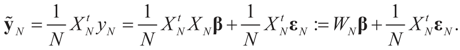

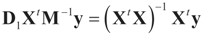

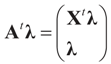

5.1.2. The Moments’ Case

Up to now, the comparison was done where the Generalized Entropy, GE, estimator was optimized under a larger space (A) than the other LS or GLS estimators. In other words, the constraints in the GE estimator are the data points rather than the moments. The comparison is easier if one performs the above comparisons under similar spaces, namely using the sample’s moments. This can easily be done if XtX is invertible, and where we re-specify A to be the generic matrix A = [XtX Xt], rather than A = [X I]. Now, let y’ ≡ Xty, X’ ≡ XtX, and ε’ ≡ Xtε , then the problem is represented as y’ = X’β + ε’. In that case the conditions for  =

=  is the trivial condition XtD2X = 0.

is the trivial condition XtD2X = 0.

=

=  is the trivial condition XtD2X = 0.

is the trivial condition XtD2X = 0.In general, when XtX is invertible, it is easy to verify that the solutions to variational problems of the type y’ ≡ Xty = XtXβ are of the form (XtX)−1Xty. In one case, the problem is to find:

while in the other case the solution consists of finding:

while in the other case the solution consists of finding:

Under this “moment” specification, the solutions to the three different methods described above (16, 23 and 24) coincide.

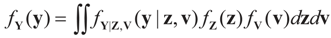

5.2. The Basic Bayesian Method

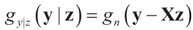

Under the Bayesian approach we may think of our problem in the following way. Assume, as before, that Cn and Cs are closed convex subsets of  and

and  respectively and that

respectively and that  and

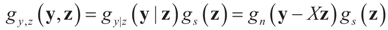

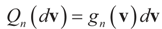

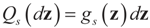

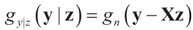

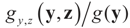

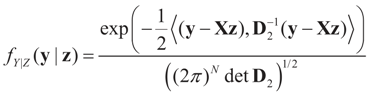

and  . For the rest of this section, the priors gn(v) will have their usual Bayesian interpretation. For a given z, we think of y = Xz + v as a realization of the random variable Y = Xz + V. Then,

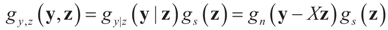

. For the rest of this section, the priors gn(v) will have their usual Bayesian interpretation. For a given z, we think of y = Xz + v as a realization of the random variable Y = Xz + V. Then,  . The joint density gy,z(y,z) of Y and Z, where Z is distributed according to the prior Qs is:

. The joint density gy,z(y,z) of Y and Z, where Z is distributed according to the prior Qs is:

and

and  respectively and that

respectively and that  and

and  . For the rest of this section, the priors gn(v) will have their usual Bayesian interpretation. For a given z, we think of y = Xz + v as a realization of the random variable Y = Xz + V. Then,

. For the rest of this section, the priors gn(v) will have their usual Bayesian interpretation. For a given z, we think of y = Xz + v as a realization of the random variable Y = Xz + V. Then,  . The joint density gy,z(y,z) of Y and Z, where Z is distributed according to the prior Qs is:

. The joint density gy,z(y,z) of Y and Z, where Z is distributed according to the prior Qs is:

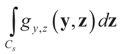

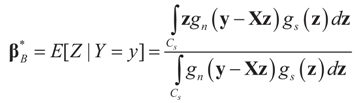

The marginal distribution of y is  and therefore by Bayes Theorem the posterior (post-data) conditional

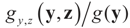

and therefore by Bayes Theorem the posterior (post-data) conditional  is

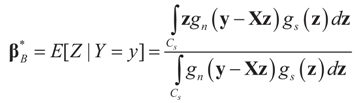

is  from which:

from which:

and therefore by Bayes Theorem the posterior (post-data) conditional

and therefore by Bayes Theorem the posterior (post-data) conditional  is

is  from which:

from which:

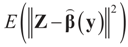

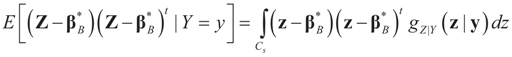

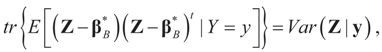

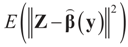

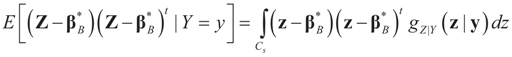

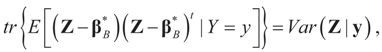

As usual  minimizes

minimizes  where Z and Y are distributed according to gy,z (y,z). The conditional covariance matrix:

where Z and Y are distributed according to gy,z (y,z). The conditional covariance matrix:

is such that:

is such that:

where Var(Z|y) is the total variance of the K random variates z in Z. Finally, it is important to emphasize here that the Bayesian approach provides us with a whole range of tools for inference, forecasting, model averaging, posterior intervals, etc. In this paper, however, the focus is on estimation and on the basic comparison of our GE method with other methods under the notations and formulations developed here. Extensions to testing and inference are left for future work.

where Var(Z|y) is the total variance of the K random variates z in Z. Finally, it is important to emphasize here that the Bayesian approach provides us with a whole range of tools for inference, forecasting, model averaging, posterior intervals, etc. In this paper, however, the focus is on estimation and on the basic comparison of our GE method with other methods under the notations and formulations developed here. Extensions to testing and inference are left for future work.

minimizes

minimizes  where Z and Y are distributed according to gy,z (y,z). The conditional covariance matrix:

where Z and Y are distributed according to gy,z (y,z). The conditional covariance matrix:

5.2.1. A Standard Example: Normal Priors

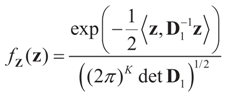

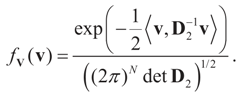

As before, we view β and ε as realizations of random variables Z and V having the informative normal “a priori” (priors for signal and noise) distributions:

and:

and:

For notational convenience we assume that both Z and V are centered on zero and independent, and both covariance matrices D1 and D2 are strictly positive definite. For comparison purposes, we are using the same notation as in Section 3. The randomness is propagated to the data Y such that the conditional density (or the conditional priors on y) of Y is:

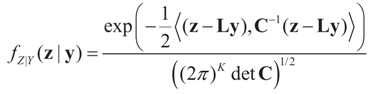

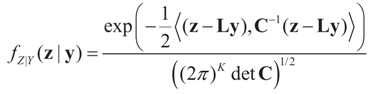

Then, the marginal distribution of Y is  . The conditional distribution of Z given Y is easy to obtain under the normal setup. Thus, the post-data distribution of the signal, β, given the data y is:

. The conditional distribution of Z given Y is easy to obtain under the normal setup. Thus, the post-data distribution of the signal, β, given the data y is:

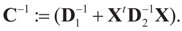

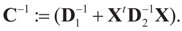

where

where  and

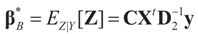

and  That is, “the posterior (post-data)” distribution of Z has changed (relative to the prior) by the data. Finally, the post-data expected value of Z is given by:

That is, “the posterior (post-data)” distribution of Z has changed (relative to the prior) by the data. Finally, the post-data expected value of Z is given by:

. The conditional distribution of Z given Y is easy to obtain under the normal setup. Thus, the post-data distribution of the signal, β, given the data y is:

. The conditional distribution of Z given Y is easy to obtain under the normal setup. Thus, the post-data distribution of the signal, β, given the data y is:

and

and  That is, “the posterior (post-data)” distribution of Z has changed (relative to the prior) by the data. Finally, the post-data expected value of Z is given by:

That is, “the posterior (post-data)” distribution of Z has changed (relative to the prior) by the data. Finally, the post-data expected value of Z is given by:

This is the traditional Bayesian solution for the linear regression using the support spaces for both signal and noise within the framework developed here. As before, one can compare this Bayesian solution with our Generalized Entropy solution. Equation (28) is comparable with our solution (14) for z0 = 0 which is the Generalized Entropy method with normal priors and center of supports equal zero. In addition, it is easy to see that the Bayesian solution (28) coincides with the penalized GLS (model (24)) for α = 1.

A few comments on these brief comparisons are in place. First, under both approaches the complete posterior (or post-data) density is estimated and not only the posterior mean, though under the GE estimator the post-data is related to the pre-specified spaces and priors. (Recall that the Bayesian posterior means are specific to a particular loss function.) Second, the agreement between the Bayesian result and the minimizer of (24) with α = 1 assumes a known value of  , which is contained in D2. In the Bayesian result

, which is contained in D2. In the Bayesian result  is marginalized, so it is not conditional on that parameter. Therefore, with a known value of

is marginalized, so it is not conditional on that parameter. Therefore, with a known value of  , both estimators are the same.

, both estimators are the same.

, which is contained in D2. In the Bayesian result

, which is contained in D2. In the Bayesian result  is marginalized, so it is not conditional on that parameter. Therefore, with a known value of

is marginalized, so it is not conditional on that parameter. Therefore, with a known value of  , both estimators are the same.

, both estimators are the same. There are two reasons for the equivalence of the three methods (GE, Bayes and Penalized GLS). The first is that there are no binding constraints imposed on the signal and the noise. The second is the choice of imposing the normal densities as informative priors for both signal and noise. In fact, this result is standard in inverse problem theory where L is known as the Wiener filter (see for example Bertero and Boccacci [37]). In that sense, the Bayesian technique and the GE technique have some procedural ingredients in common, but the distinguishing factor is the way the posterior (post-data) is obtained. (Note that “posterior” for the entropy method, means the “post data” distribution which is based on both the priors and the data, obtained via the optimization process). In one case it is obtained by maximizing the entropy functional while in the Bayesian approach it is obtained by a direct application of Bayes theorem. For more background and related derivation of the ME and Bayes rule see Zellner [38,39].

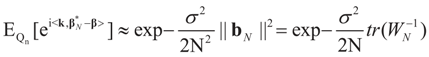

5.3. Comparison with the Bayesian Method of Moments (BMOM)

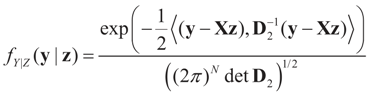

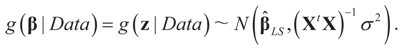

The basic idea behind Zellner’s BMOM is to avoid a likelihood function. This is done by maximizing the continuous (Shannon) entropy subject to the empirical moments of the data. This yields the most conservative (closest to uniform) post data density (Zellner [14,40,41,42,43]; Zellner and Tobias [15]). In that way the BMOM uses only assumptions on the realized error terms which are used to derive the post data density.

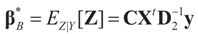

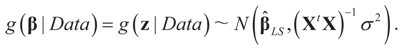

Building on the above references, assume (XtX)−1 exists, then the LS solution to (1) is  which is assumed to be the post data mean with respect to (yet) unknown distribution (likelihood). This is equivalent to assuming

which is assumed to be the post data mean with respect to (yet) unknown distribution (likelihood). This is equivalent to assuming  (the columns of X are orthogonal to the N × 1 vector E[V|Data]). To find g(z|Data), or in Zellener’s notation g(β|Data), one applies the classical ME with the following constraints (information):

(the columns of X are orthogonal to the N × 1 vector E[V|Data]). To find g(z|Data), or in Zellener’s notation g(β|Data), one applies the classical ME with the following constraints (information):

and:

and:

where

where  is based on the assumption that

is based on the assumption that  , or similarly under Zellner’s notation

, or similarly under Zellner’s notation  , and σ2 is a positive parameter. Then, the maximum entropy density satisfying these two constraints (and the requirement that it is a proper density) is:

, and σ2 is a positive parameter. Then, the maximum entropy density satisfying these two constraints (and the requirement that it is a proper density) is:

which is assumed to be the post data mean with respect to (yet) unknown distribution (likelihood). This is equivalent to assuming

which is assumed to be the post data mean with respect to (yet) unknown distribution (likelihood). This is equivalent to assuming  (the columns of X are orthogonal to the N × 1 vector E[V|Data]). To find g(z|Data), or in Zellener’s notation g(β|Data), one applies the classical ME with the following constraints (information):

(the columns of X are orthogonal to the N × 1 vector E[V|Data]). To find g(z|Data), or in Zellener’s notation g(β|Data), one applies the classical ME with the following constraints (information):

is based on the assumption that

is based on the assumption that  , or similarly under Zellner’s notation

, or similarly under Zellner’s notation  , and σ2 is a positive parameter. Then, the maximum entropy density satisfying these two constraints (and the requirement that it is a proper density) is:

, and σ2 is a positive parameter. Then, the maximum entropy density satisfying these two constraints (and the requirement that it is a proper density) is:

This is the BMOM post data density for the parameter vector with mean  under the two side conditions used here. If more side conditions are used, the density function g will not be normal. Information other than moments can also be incorporated within the BMOM.

under the two side conditions used here. If more side conditions are used, the density function g will not be normal. Information other than moments can also be incorporated within the BMOM.

under the two side conditions used here. If more side conditions are used, the density function g will not be normal. Information other than moments can also be incorporated within the BMOM.

under the two side conditions used here. If more side conditions are used, the density function g will not be normal. Information other than moments can also be incorporated within the BMOM.Comparing Zellner’s BMOM with our Generalized Entropy method we note that the BMOM produces the post data density from which one can compute the vector of point estimates  of the unconstrained problem (1). Under the GE model, the solution

of the unconstrained problem (1). Under the GE model, the solution  satisfies the data/constraints within the joint support space C. Further, for the GE construction there is no need to impose exact moment constraints, meaning it provides a more flexible post data density. Finally, under both methods one can use the post data densities to calculate the uncertainties around future (unobserved) observations.

satisfies the data/constraints within the joint support space C. Further, for the GE construction there is no need to impose exact moment constraints, meaning it provides a more flexible post data density. Finally, under both methods one can use the post data densities to calculate the uncertainties around future (unobserved) observations.

of the unconstrained problem (1). Under the GE model, the solution

of the unconstrained problem (1). Under the GE model, the solution  satisfies the data/constraints within the joint support space C. Further, for the GE construction there is no need to impose exact moment constraints, meaning it provides a more flexible post data density. Finally, under both methods one can use the post data densities to calculate the uncertainties around future (unobserved) observations.

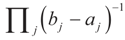

satisfies the data/constraints within the joint support space C. Further, for the GE construction there is no need to impose exact moment constraints, meaning it provides a more flexible post data density. Finally, under both methods one can use the post data densities to calculate the uncertainties around future (unobserved) observations. 6. More Closed Form Examples