Abstract

The present study aims to investigate the effects of macroeconomic variables on stock price crash risk in the economically uncertain conditions of Iran’s market. This study also seeks to examine whether there is a significant relationship between some firm characteristics and falling stock prices. The sample of the study includes 152 Iranian companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) between 2014 and 2019. Furthermore, the research model has been estimated using a fixed effect pattern, and the DUVOL (down-to-up volatility) measure is defined as a proxy for stock price crash risk. Consistent with our expectations, the results show that there is a positive association between the inflation and unemployment rates and stock price crash risk, whereas the GDP and exchange rates are correlated negatively with crash risk. In fact, with rising inflation and unemployment, on the one hand, the amount of savings and the purchasing power of the people have decreased, and on the other hand, it has reduced the sales of companies due to the increase in the pricing of manufactured products. In Iran’s economically uncertain situation due to sanctions, managers are trying to overstate financial performance and conceal bad news to have better access to financing; so, when the total amount of bad news accumulated over time reaches a tipping point, it leads to a stock crash. It also appears that when the exchange rate rises, Iranian investors prefer to buy companies’ shares to maintain the purchasing power of their money. Outcomes also confirm that larger firms and those with higher Return on Assets (ROA) are more sensitive to crash risk.

1. Introduction

Sudden changes in stock prices have attracted the attention of many academics and professionals in the capital market during recent years. Thus far, there has been a lot of research around the world about the impact of firm-level factors on stock price crash risk, some of which were internal factors, and some external. For example, many studies have focused on firm-level internal factors such as corporate tax avoidance [1], opaque financial reports [2,3], accounting conservatism [4], corporate social responsibility [5], CEO overconfidence [6]), financial constraints [7], stock liquidity [8], corporate financing [9], corporate debt maturity [10], stock ownership [11], equity incentives [12], corporate governance [13], and other cases. However, several other studies on factors such as religion [14,15], social trust [16], media sentiment and mawkishness [17], individualism [18], political connections [19], trading behavior and sentiment of investors [20,21], and product market competition [22] have tried to investigate a couple of these corporate external factors. This study has a slightly different approach and aims to examine simultaneously the effects of some corporate characteristics as well as the most important macroeconomic external factors on the stock price crash. Since most of the prior studies have focused on firm-level factors, and few studies have taken a more general look at this issue and considered macroeconomic factors, our study examines both dimensions simultaneously in Iran’s economic crunch, which can be of great help to the research literature. Our research focuses on the emerging Iranian market, which has experienced unfavorable economic relations with European countries and the United States in recent years due to severe economic sanctions, resulting in increasing the systematic risk and insecurity of the Iranian market for investors and lenders. Undoubtedly, researching a systematic high-risk market, whose managers have high opportunistic motivations and where investor emotional behavior fluctuates sharply, can be very challenging.

As for Iran’s market, it can be stressed that Iran has faced the most severe economic sanctions in recent years, leading to most of its companies having many financial difficulties [23,24]. Economic sanctions against Iran have been so severe that gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen sharply in recent years, and the national currency’s value is depreciating more and more due to the dramatic rise in the exchange rate. In such an unfortunate economic situation, the supply of raw materials required by companies is very expensive, increasing the cost of products. In such an inflationary economy, where prices are rising day by day, people’s purchasing power will decrease over time; as a result, there will be a significant reduction in the demand for manufactured goods in Iran’s market. Despite heavy production costs as well as declining sale levels, companies are not only unable to hire new workforce but also have to lay off most of them to reduce costs, which ultimately raises the unemployment rate in society. As rising inflation reduces people’s purchasing power and the sale levels of companies, as well as rising unemployment reducing the income level and well-being of individuals, companies are expected to face many difficulties in financing themselves through the issuance of shares, which can eventually decrease stock prices. Besides, under these disaster economic circumstances, creditors are less willing to lend to companies with lower profits [24].

Based on the existing research literature, asymmetric information and heterogeneous investor belief could be main reasons for the sudden fall in stock prices [25,26,27]. Thus, owing to the existence of information asymmetry in Iran’s market, Iranian managers have strong motivations for manipulating accounting figures to show their financial performance as better and to attract more attention from investors and creditors [23,24,25,26,27,28]. In other words, since lenders and investors cannot simply trust such companies with a high risk of collapse, firms are keen on showing a beautiful picture of their financial situation and do not disclose negative information [28,29]. Another interesting point is that negative attitudes cannot be expressed suddenly, and make the stock price crash when they finally come out [25]. According to Hong and Stein [30], as there are short-sales limitations in the market, bearish investors do not firstly engage in the market, and their information is not shown in prices. If other, earlier, bullish investors escape from the market, the originally bearish traders might become marginal “support buyers”, and more will be known about their signals. Consequently, accumulated concealed information comes out during market drops.

According to agency theory, given Iran’s economically uncertain atmosphere that has been created by sanctions, there is a wide range of motivations such as rewards contracts and management tenure that encourage managers to refrain from disclosing negative information, and accumulating it within a company [26,30,31,32,33]. In times of economic uncertainty, corporate directors are not likely to disclose bad news, as investors hardly get complete information under uncertainty, and investors have greater disagreement about stock prices and negative views are hidden because of short-sales constraints. [25,34]. In general, managers’ efforts to make a business unit look good need to conceal negative information and news. If managers refuse to disclose it for a long time, negative news will accumulate within a company. On the other hand, the amount of bad news that managers can accumulate is limited. That is because when the volume of accumulated negative news reaches a certain threshold, it will be impossible and costly to not disclose it for a longer period. As a result, the mass of bad news suddenly enters the market after reaching its peak, and this leads to a stock price crash [23].

This paper contributes to the research literature in several ways. First, our study enriches the literature on determinants of stock price crash risk. We provide evidence that macroeconomic variables add to firm-specific stock price crash risk, and claim that this impact can appear as managers’ motivations to withhold negative news boost in economically uncertain periods, where systemic risk has increased sharply because of severe sanctions. Second, we show the influence of corporate features on crash risk. When a country’s economy is facing a financial crisis, different characteristics of companies such as firm age, firm size, sale growth, ROA, and leverage could help in recognizing companies that would have bigger increases in stock crash risk. As a final point, to our knowledge, this study may be one of the first studies to substantiate that adverse macroeconomic trends have a significant impact on aggregated crash risk in times of financial crisis.

The rest of the aforementioned research is organized as follows: the next section frames the study into a theoretical framework, hypotheses development, and literature. Section 3 presents the research design and outlines where data are obtained and the sample selection procedure. Section 4 then explains the main results and the implications drawn from statistical analyses, and, finally, the last segment indicates the concluding remarks.

2. Research Background and Hypotheses Development

Various theories have been put forward to explain the causes of falling stock prices concerning financial market mechanisms and investor behavior. On explaining how the phenomenon of falling stock prices occurs, it can be noted that a decrease in a company’s stock price increases its financial and operating leverage, and, in turn, results in fluctuations in stock returns, and this symmetrical reaction leads to a negative skew of stock returns [35,36,37]. According to modern financial theories, the value of a stock is equal to the sum of the present value of its future cash flows. Based on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), a stock price in an efficient market fluctuates within its intrinsic value range, but sometimes due to a shock-like release of new information, prices rise dramatically without any fundamental or economic justification. This process is referred to in the financial literature as the price bubble. In this regard, Blanchard and Watson [38] argue that the negative skewness of stock returns or falling stock price crash is a result of the bursting of price bubbles. Moreover, Campbell and Hentschel [39] proposed a reverse oscillation mechanism to explain the phenomenon of falling stock prices or negative skewness of stock returns [39]. Accordingly, the entry of new information into the market, both favorable and unfavorable, will lead to increased market volatility, and therefore the risk premium will increase. Although this increase in risk-taking somewhat reduces the positive effect of good news, it reinforces the negative effect of bad news. Therefore, a decrease in stock prices due to the entry of unfavorable news into the market will be greater than an increase due to the entry of favorable information, by which this mechanism finally leads to a fall in stock prices [32].

Reviewing the research literature, it is easy to see that managerial bad news hoarding has always been one of the key factors in the sudden fall in stock prices in various financial markets. The fundamental question now arises as to why, in uncertain economies like Iran, managers are more motivated to avoid exposing bad news to the market. A company’s profit is one of the important items of financial statements that have attracted the attention of investors and managers. On the one hand, investors use earnings per share forecasts to form a profitable stock portfolio, and on the other hand, managers use them to make important decisions such as operating budgeting, capital expenditures, and other decisions related to the allocation of company resources [40]. Managers’ forecasts of profit are optional; however, economic reasons have also been provided for this. For example, concerns about the cost of disclosing, buying, and selling stocks internally, and fears of laws that could affect the management’s decision to release voluntary bad news forecasts are among the reasons for managers’ profit forecasts. Various studies on management earnings forecasts have suggested that these forecasts have informational content; therefore, the publication of such forecasts causes sharp volatility in prices [41,42]. According to Kim et al. [6], the decisions and forecasts of managers will be affected by the economic conditions of each country. As a result, managers, under the influence of internal factors, make decisions about the company’s activities. Therefore, to the extent that these internal factors depend on the economic situation of the country, it is expected that the managers’ forecasts will reflect the existing expectations regarding the economic variables’ situation [6]. Therefore, in a country like Iran, which suffers from a high inflation economy, the effect of macroeconomic variables such as GDP, inflation rate, unemployment rate, and exchange rate can affect the accuracy of managers’ profit forecasts.

In an unfavorable economic environment, managers have very strong incentives to manipulate financial statements and keep the bad news secret, owing to a range of reasons such as career anxieties, compensation contracts, attracting investors’ attention, and gaining lenders’ trust [23,25,31,32,43]. According to agency theory, given personal motivations and interests such as reward contracts and job positions, managers tend to avoid spreading bad news and accumulate it within the company [23,26,31,33]. Concealment of bad news by managers continues for a certain threshold, and when it reaches its peak, it is impossible and costly to continue to not disclose it, and the manager will be forced to release it. After that, a huge amount of bad news suddenly enters the market and leads to an abrupt, significant, and negative drop in stock price, or stock price crash [2,23,25,34]. In fact, in a financial market, stock prices are more likely to fall when managers are motivated enough to hoard negative events.

Since the Iranian market is facing uncertainty and instability due to severe economic sanctions in recent years, is by no means a safe place for investors and creditors. Therefore, we argue that unfavorable trends in the macro-economy, including a sharp drop in GDP and a remarkable increase in inflation, unemployment, and exchange rates can affect firm-specific stock price risk, as it influences managerial bad news hoarding behavior. Iranian firms’ operations are facing greater uncertainty due to severe economic sanctions, resulting in greater volatilities in future earnings and cash flows. In confirmation of this key point, Luo and Zhang [30] also believed that economic instability in a market will worsen the financial condition of companies in the short term; hence, in such circumstances, managers have a high incentive to manage profits to slightly reduce their short-term financial pressures [34]. In an unstable market where prices fluctuate every day, it is very difficult for investors to obtain reliable information. Therefore, investors and creditors have to rely on the information provided by companies, which increases the power and ability of managers to overstate financial statements and hide negative information [34,44]. Therefore, given the acute economic conditions of the Iranian market caused by sanctions, Iranian managers are expected not to release negative information and news due to a variety of factors like facilitating corporate financing, compensation contracts, and job concerns.

Over the past decade, many attempts have been made to examine the relationship between macroeconomic variables and stock returns [45,46,47]. Previous research supports the view that stock prices reflect the present value of future cash flows, and therefore both future cash flows and expected return rates are required [48]. According to the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, gross domestic product (GDP) is one of the most important macroeconomic variables in the country, which reflects the overall result of economic activities [30]. GDP is an indicator through which one can be informed about the growth and decline of the entire economy. As a matter of the fact, components of GDP are consumption expenditures of the private sector, investment expenditures of the private sector, public sector expenditures, net exports, etc. Another important point is that by examining the components of GDP, investors generally find out whether the economy has good growth and stability for investing in companies or not [30]. Investors can also make better investment decisions by knowing which component the sharp fluctuations are related to. In general, it is important to pay attention to the composition of components of GDP and its growth rate in making investment decisions [47]. One of the factors affecting the stock market index is economic growth during business cycles. Economic prosperity affects investors’ expectations of the activities’ profitability and investment confidence. Increasing economic growth reduces economic uncertainty and increases the expected return on investment. These factors, along with the increase in wealth, lead to an increase in demand for a variety of assets, including stocks, and thus to their price increases. Besides, any change in stock prices affects the wealth and consumption of households, as well as the investment and production of firms [49].

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Iran’s gross domestic product has plummeted in recent years due to unprecedented sanctions. US and Western economic sanctions against Iran have severely damaged the entire body of the Iranian economy and intensified fluctuations in macroeconomic variables, which has led to a high level of uncertainty and instability in the Iranian market. In conditions of economic uncertainty, high fluctuations in macroeconomic variables strongly affect stock prices in the Iranian market, and investment risk assessment is very complex and difficult for investors because managers refrain from disclosing bad news to gain better access to financing [23,24,43,47,50]. As for Iran, it is a resource-rich and labor-rich nation in the Middle East that is famous for being the second-largest oil producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Iran’s oil and gas reserves also have a high rank among the world’s top powers. On average, more than four fifths of Iran’s total exports are related to the sale of oil and gas, which is the main source of revenue in the government budget, and many industries and economic infrastructures are financed from their funds [47]. Accordingly, when budget deficits in a country increase, stock returns are likely to decline strikingly [51].

The government of the USA has banned most companies and banks all over the world from doing business with Iran, which has left Iranian firms with not only a lack of export earnings but also severe problems in obtaining raw materials for their production, strongly affecting corporate profitability. Iran has also been deprived of the import and export of many valuable and basic goods, including oil and gas, and has suffered a dramatic drop in national income, which has caused irreparable damage to various industries [47]. Thus, severe economic sanctions against Iran in recent years have caused GDP to decline sharply, making it a very unsafe and risky place for investment for both domestic and foreign investors, as well as creditors in the Iranian market. In this regard, Rad and Ghorashi [52] confirmed that GDP has a positive impact on TSE (Tehran stock exchange) firms’ stock price in the long- and short-run. Therefore, Iranian companies are expected to refrain from disclosing the adverse effects of the current economic situation on the financial performance of their companies to present a better corporate financial image. When performance pressures on managers over certain periods are so great, they engage in profit management actions that ultimately lead to stock falls [53]. As mentioned earlier, when hiding the negative effects of the current economic situation on companies’ financial performance reaches its peak, managers are forced to disclose them. Due to the sudden influx of a lot of negative information, a fatal blow enters the market and causes severe fear and anxiety to investors, which causes stock prices to fall [23]. Therefore, we predict that there is a negative relationship between GDP and stock price crash risk. This means that, in the context of economic uncertainty, in which the GDP rate is declining and has a negative impact on the financial situation of companies [30,54,55], Iranian executives are expected to prevent bad news from entering the market, which leads to falling stock price suddenly [23].

Hypothesis 1.

There is a negative relationship between GDP and stock price crash risk.

In the financial literature, inflation has been considered as one of the most important economic variables affecting stock prices [45,46,53,56,57]. Market equilibrium does not arise based on nominal values, and investors consider inflation to be one of the most important macroeconomic variables influencing investment decision-making. The real rate of return is the annual percentage of profit earned on an investment, adjusted for inflation. Therefore, the real rate of return accurately indicates the actual purchasing power of a given amount of money over time. Adjusting the nominal return to compensate for inflation allows the investor to determine how much of a nominal return is a real return. If inflation is well predictable, investors will simply add a percentage as inflation to their expected returns and the market will reach equilibrium. In the case of inflation, the average nominal profit of companies increases over time. Profitability has not increased, but nominal profit has increased under the influence of inflation. As the nominal profit increases, the nominal stock price will also increase. Another effect of inflation is that it reduces the intrinsic value of each share. In the Iranian market, where the inflation rate is growing rapidly year by year, the quality of companies’ real profits (economic profits) are predicted to have decreased.

According to Moradi et al. [24], the reason for the abnormal increase in stock prices in Iran’s inflation economy is quite justifiable. A predictable response to declining purchasing power is to buy now, rather than later. Moradi et al. [24] argue in Iran’s inflationary economy, as the value of various assets increases, so does the value of corporate stocks as an asset. Therefore, instead of keeping cash, people prefer to invest their money in the stock market so that their purchasing power does not diminish. Unfortunately, the urge to spend and invest in the face of inflation tends to increase inflation in turn, generating a potentially disastrous feedback loop. When people and businesses spend more rapidly to lessen the time they hold their depreciating currency, the economy finds itself awash in cash no one particularly wants. This implies that the supply of Iran’s money exceeds the demand, and the purchasing power of currency falls at an ever-faster rate. Another important point is that the unemployment rate in Iran is relatively high and the government must lower interest rates. As long as interest rates are low, Iranian firms and individuals can borrow cheaply to start a business and hire new workers, encouraging spending and investing, which generally trigger inflation in turn.

Further, in an inflationary economy where prices are constantly rising and people’s purchasing power is declining, on the one hand, the wages of the workforce in companies are increasing, and on the other hand, the supply of raw materials by companies is more expensive [58,59]. In general, as mentioned, in the inflationary economy of Iran, investors’ emotional behavior causes stock prices to rise too much without any scientific reason. Iranian investors are often seen to buy stocks without checking the financial condition of companies because they think that by keeping their capital in cash, they will lose money in the face of inflation [24]. In other words, the current price of the stock is higher than its real value, and there is a possibility of a bubble bursting and the stock falling. As a significant increase in the cost of supplying raw materials for production as well as the wages of the labor force affects the sales and profitability of companies negatively [59], managers have strong motivations for hoarding bad news, leading to a sudden fall in stock price. Therefore, according to the points made about the Iranian market, the second research hypothesis predicts as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

There is a positive relationship between the inflation rate and stock price crash risk.

As highlighted before, many companies are collapsing due to heavy sanctions against Iran [23,24,28,29]. Therefore, to reduce costs, not only can they not hire new staff, but they also have to lay off many employees, resulting in a surging unemployment rate. When a country like Iran does not have good economic growth and its GDP is negative, many companies and industries are likely to go bankrupt and cannot hire new labor. That is why the GDP and unemployment rate are always moving in the opposite directions, which is consistent with Arthur Okan’s law from 1962 [60,61]. Thus far, various studies have concluded that the unemployment rate has had a significant impact on the stock markets of developing countries [62,63,64]. Lack of unemployment insurance, very limited access to social protection, and lower income levels in labor markets among developing nations can be the main causes of such a relationship [64,65]. In the same vein, Nallareddy and Ogneva [66] confirmed that the GDP and unemployment rate affect corporate earnings growth. Hence, when the unemployment rate rises, the level of income and well-being of people decreases, and they cannot spend part of their income to invest in the stock market, resulting in a price drop because of reduced demand for the stock market.

Hypothesis 3.

There is a positive relationship between the unemployment rate and the stock price crash’s risk.

The exchange rate can affect companies’ financial performance in two ways: firstly, the income of companies importing and exporting goods and services is directly related to the exchange rate; and secondly, the exchange price as a competing asset in the economic portfolio influences investors’ decisions to buy and sell stocks. Looking at the research literature, there is a lot of robust evidence of a significant relationship between the exchange rate and the stock price of companies in different markets [67]. For example, Sui and Sun [68] found a strong connection between exchange rates and stock returns in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa during the financial crisis. Dahir et al. [69] also realized exchange rates and stock returns are positively correlated in the medium and long term. However, Bahmani-Oskooee and Saha [70] investigated data from 24 countries and concluded that the effects of exchange rate changes on stock prices could be asymmetric. Based on data from East Asian markets, the results showed the type of relationship between the exchange rate and the stock price depends on several factors such as exchange rate regimes, the trade size, the degree of capital control, and the size of the equity market [67]. In a study conducted in the Persian Gulf region, the results of Parsva and Lean [71] confirmed bidirectional causalities in the countries of Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia after the crisis period, while there is a causal relationship between stock prices and exchange rate in Iran before and after the financial crisis. They also believe that fluctuations in foreign exchange markets can considerably affect stock markets in the Middle East.

Due to pressure from the US government and Western countries, most Iranian companies have been largely banned from all exports to other countries [43]. Given the severe sanctions imposed on Iran during recent years, fluctuations in the exchange rate have caused some problems for Iranian companies. In this regard, research conducted in Iran has shown that fluctuations in liquidity and trade balance lead to fluctuations in current expenditures, and ultimately lead to high inflation. Therefore, such an increase in society’s liquidity does not lead to an increase in GDP and is a factor in exacerbating inflation [47]. As mentioned earlier, uncertainty in macroeconomic variables can make it difficult for managers to accurately predict a company’s profits. Thus, economic variables such as exchange rates can affect the accuracy of profit forecasts by managers. Given the significant effects of the exchange rate on corporate activity, if the exchange rate fluctuates as a macroeconomic indicator, it is natural that the accuracy of managers’ forecasts will also fluctuate. Therefore, Iranian managers are expected to hoard negative news so that their predictions remain attractive to market investors. Given the problems Iranian firms have with financing, managers are constantly trying to make better predictions about their future corporate performance and to not disclose specific information about the negative effects of the exchange rate increase so that they can motivate investors to buy more shares of their companies. In addition to all these cases, the Iranian investors in the inflationary conditions of the Iranian market, which is witnessing the loss of the national currency value, try to buy shares so as not to suffer losses. We anticipate that, due to such high pressure in the market for buying stocks due to the exchange rate increase, the probability of an increase in stock prices will increase.

Hypothesis 4.

There is a negative relationship between the exchange rate and stock price crash risk.

3. Research Methodology

This paper is applied research, and the total data needed to test the hypotheses were collected directly from the financial statements on the Tehran Stock Exchange official website [72], Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran (CBI) [73], Iran’s profile on the website of the World Bank [74], and Iran’s profile on the website of the International Monetary Fund [75]. The study population consists of 912 observations and 152 firms listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) during the years 2014–2019. Longitudinal data has the characteristics of cross-sectional data and time series data simultaneously. Building on econometrics, if research data are longitudinal, the type of estimation of a model must first be determined. In the first phase, it is essential to specify whether a model fits the ordinary least squares (OLS) or the panel data method. The F-Limer test was used for this purpose. In the Chow test, the non-acceptance of the null hypothesis means that the model must be estimated via a panel data pattern and pooled data model (OLS model). Furthermore, if the use of the panel data method in the previous section is confirmed, the Hausman test is used to determine whether panel data with fixed effects or panel data with random effect is appropriate [24,29]. Additionally, a variance inflation factor (VIF) test to investigate the severity of multicollinearity; a Durbin–Watson test to detect the problem of serial autocorrelation among residuals; and a Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test to investigate heteroskedasticity problems were used in this study.

3.1. Study Sample

The target population included all companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange during the period 2014 to 2019. In summary, common features of the companies to determine the population are as follows:

- The type of business activity is productive. Therefore, investment companies, leasing, credit, financial institutions, and banks are not included in the sample. The reason for this is the different nature of the operations of these companies, some laws, and different accounting standards developed for the companies that are active in the above industries.

- The financial periods of the companies should be finished at the end of the solar year to enhance the comparability and homogeneity of the companies in terms of time.

- The firms do not have a trading halt for more than 6 months during the fiscal year.

- According to the research period (2014–2019), a company must be available on the Tehran Stock Exchange before the year 2014, and its name should not be removed from the listed companies by the end of 2019.

Taking account of the above conditions, a sample size of 152 TSE firms has been selected.

3.2. Research Model

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of the most important macroeconomic variables in Iran on the risk of sudden stock collapse. We are looking to see if severe sanctions, which have led to economic uncertainty in the Iranian market, will cause a sharp drop in stock prices. Therefore, the following multivariate regression model was used to test the research hypotheses:

where crash risk is defined as a dependent variable. Among the various methods of measuring stock crash risk, due to the widespread use of the down-to-up volatility (DUVOL) method in most domestic research in the Iranian market and also international studies around the world [34,76], this approach has been used in this paper to compare our results with others homogeneously and uniformly. Similar to many previous studies such as Hu and Wang [76] and Luo and Zhang [34], we use the DUVOL criterion to measure the stock price crash risk. In other words, our measure is the asymmetric volatility of negative vs. positive returns (DUVOL). For each firm over a fiscal year, we separate all the weeks with firm-specific weekly returns below the annual mean (“down” weeks) from those with firm-specific returns above the annual mean (“up” weeks) and compute the standard deviation for each of these subsamples distinctly [30,34,76]. In the equation below, is the number of “up” weeks, is the number of “down” weeks. In short, companies with a higher DUVOL value are more prone to crashing.

GDP, inflation, unemployment, and currency are regarded as independent variables in this study. Besides, some corporate characteristics such as financial leverage, ROA, sale growth, firm size, and firm age are considered as control variables. In the literature of previous research, it has been proven that each of our control variables can have potential effects on the risk of falling stock prices [30]. To sum up, the calculation of each of the variables of this research is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions.

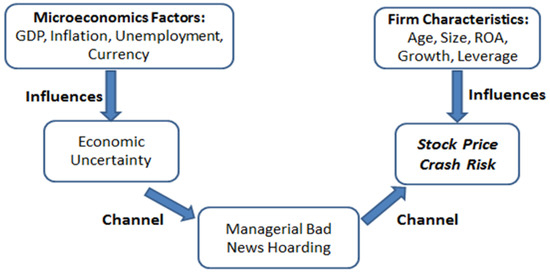

During the financial crisis in the Iranian market due to severe economic sanctions, our research view is based on the principle that sharp fluctuations in macroeconomic variables strengthen managerial bad news hoarding incentives and abilities, which is an important determinant of crash risk. Firms’ fundamentals also affect crash risk, as managers are expected to distort financial information because investors hardly get complete information under economically uncertain conditions. Thus, information asymmetry between managers and investors can be the main factor in the stock price crash risk. The graphical framework related to the main idea of this research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the study. Source: Own research.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze more about the data collected. In this section, information on mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

What stands out from Table 2 is that sanctions against Iran have been so severe that Iran’s economic growth has averaged less than one percent in recent years. Besides, on average, the inflation and the unemployment rates are 17 and 12 percent, respectively, which show the economic uncertainty and the acute financial situation of the country. Moreover, on average, companies have been operating in the TSE market for nearly 19 years, which indicates their high experience, while the rate of return on their assets is approximately 10%. The leverage variable clearly shows that most of the Iranian firms’ assets are financed by debt, too.

4.2. Unit Root Test

In statistics, a unit root test tests whether a time series variable is non-stationary and possesses a unit root. The null hypothesis is generally defined as the presence of a unit root and the alternative hypothesis is stationary. Hence, in Table 3, a Levin–Lin–Chu test is used to investigate the existence of a unit root in combined data.

Table 3.

Unit Root Test.

Building on the results of the unit root test, since the amount of P-value for all variables is less than 0.05%, we concluded that our research variables are stationary, indicating efficient regression and very accurate results. As a result, all the variables of our paper are real and stationary, and are not obstructed for the use of OLS regression or panel data.

4.3. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

In this study, since our residuals are normally distributed and homoscedastic, we do not have to worry about linearity. Multicollinearity is a phenomenon in which one predictor variable in multiple regression models can be linearly predicted from the others with a substantial degree of accuracy. In statistics, the variance inflation factor (VIF) evaluates the severity of multicollinearity in regression analysis [30]. Information about the collinearity diagnostics is shown in Table 4 as follows.

Table 4.

Collinearity Diagnostics.

Regarding the VIF, if the VIF of the estimated model coefficients is less than 10, there would be no linearity problem. Based on the table above, this value is less than 10 for all research models, which means that there is no linearity concerning the research hypotheses [24].

4.4. Results of the Research Model

The results of each of the hypotheses of this research are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The results of the research model.

To investigate heteroskedasticity problems, a Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test was employed in this study [24]. As the amount of its probability was 0.08, and greater than five percent, there are no heteroskedasticity problems with the research model. Another regression assumption suggests error sentences were not significantly correlated. If errors are correlated together, they are said to be involved in autocorrelation. To detect the problem of serial autocorrelation among residuals, the Durbin–Watson test can be employed [24,77,78]. Given that the amount of the Durbin–Watson statistic was 2.32 (between 1.5 and 2.5), the lack of serial autocorrelation in residuals was moderately evident. Another important point is that we need to conduct an F-Limer (Chow) test at first to determine if the model should be the common effect model (pooled) or the fixed effects model [24]. In the F-limer test, failing to reject the null hypothesis means that the research model must be estimated via the common effects model [24,79]. In the second phase, if the results of the Chow test indicate that the pooled research model is appropriate, then the Hausman test is needed to determine whether the fixed effects model or the random-effects model is appropriate [24,76,77,78,79,80,81]. As for the Hausman test, if the null hypothesis (H0) is supported, then there is no significant correlation between individual effects and model error, showing that the individual effect’s values are randomly generated and the research model must be estimated with a random-effects pattern [24]. Since the results of the F-limer test’s probability was 0.02, and less than five percent, the fixed effects model is acceptable. Now, our research model should be estimated with a fixed effect pattern due to the Hausman test’s probability being less than five percent.

The results show there is a negative association between the GDP and exchange rate and the stock price crash risk, whereas the inflation rate and unemployment rate are linked negatively to a sudden fall in stock prices. Systematic risk factors affect all companies in an economy. However, while companies can respond to systematic risk factors, they cannot remove them [82]. Therefore, in economically uncertain conditions, managers are expected to be more inclined to hoard negative news so as not to damage the image of the company’s financial situation, and when this news reaches its peak and enters the market, it causes a rapid fall in stock prices [23,30,34]. Even though companies face many financial problems in the face of sanctions and do not have good potential for growth, investors have opposing views, and try to buy the shares of these companies because, with the increase of the exchange rate, their purchasing power decreases every day. Thus, they assume the stock market could be a safe place to invest in an inflationary economy. Generally, consistent with our expectations, Iran’s economic uncertainty due to severe sanctions is associated with a stock price crash through its relation with the manager’s bad news hoarding behavior and investors’ heterogeneous beliefs. In the unsafe and unstable economic conditions of the Iranian market, our evidence also shows that larger stocks, as well as those with higher rates of return, have been much more sensitive to crash risk.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Iran’s government has had heavy sanctions imposed by the US and Western countries during recent years to curb nuclear activities [43]. Severe economic sanctions against Iran have weakened the Iranian market, and most of its companies are facing the worst financial problems [23,24,43,50]. Evidence show boycotted countries have several problems with providing their goods and paying cash, and with trading activities such as import and export, influencing the exchange rate [23]. After all, as the problems in the Iranian capital market increase, the attitudes of foreign and domestic investors towards this market have deteriorated, and creditors are reluctant to lend to companies with a high bankruptcy probability, which has made it more difficult for Iranian companies to access finance [24]. Severe fluctuations in macroeconomic variables have caused instability, insecurity, and economic uncertainty in the Iranian market. Hence, this paper aimed at proving the fact that Iran’s economic uncertainty is positively related to stock price crash risk, as managers’ incentives and abilities to withhold bad news are an important determinant of crash risk.

Our findings show that the worse the country’s economic trend (negative GDP) is, the lower the value of corporate stocks, which is consistent with the studies of Hong and Stein [30], Rad and Ghorashi [52], Udegbunam and Eriki [54], and Hong and Abdul Razak [55]. Furthermore, since GDP and unemployment rates are always moving in opposite directions [61], the results show that, with the decline in GDP, the unemployment rate has risen sharply, and this has increased the risk of falling shares of Iranian companies. In other words, when a country is facing sanctions and its GDP is negative, many companies in various industries are on the verge of bankruptcy, and to reduce operating costs, not only can they not hire new labor, but they have also been forced to dismiss their workers. Lack of unemployment insurance, very limited access to social protection, and lower income levels in labor markets among developing countries have caused the unemployment rate to affect the amount of demand in the stock market [65]. Thus, similar to the studies of [62,63,64,65], our research findings proved an increase in the unemployment rate reduces the level of income and savings of the people, lowers the demand for the stock market, and ultimately leads to a fall in prices.

The outcomes also document that there is a positive relationship between the inflation rate and stock price crash risk, which is very close to the thoughts of Moradi et al. [24] in the context of Iran. This implies that inflation, on the one hand, reduces the purchasing power of individuals, and, on the other hand, increases the cost of products, both of which simultaneously have a significant impact on the sales of companies [58,59]. In such a situation where the actual sales of companies reduce, managers tend not to release bad news about the company’s operations because it may negatively affect the decisions of investors, which will eventually lead to a fall in stock prices. We also find that there is a negative association between exchange rate and stock price crash risk, which is in line with the findings of [67,68,71]. The existence of such a significant relationship in the Iranian market is quite justifiable from two perspectives. First, in a sick economy, when there is increased fluctuation in companies’ profits and cash flow, managers are expected to distort financial information. The key point is that investors have to trust the information reported by managers as they hardly get complete information under economically uncertain conditions. As a result, it deteriorates information asymmetry between corporate insiders and outside investors and this encourages managers to manipulate accounting figures [25,34]. Second, since investors’ beliefs in the market are different, a large number of Iranian investors assume that, in times of economic uncertainty, companies’ stocks are the best way to invest, because stocks, like other assets, rise when the exchange rate rises. Finally, looking at the details, we found that negative news hoarding by managers has probably been higher in large companies and those with high asset returns than in other companies, which has eventually led to a fall in stock prices. It seems that these larger firms try to show their financial performance as more attractive so that they can have better access to financing during the economic crisis, while managerial bad news hoarding behavior is less common among older companies.

In general, our findings would have practical implications for market participants in developing markets. By understanding the influence of macroeconomic variables on crash risk, investors could adjust their investments accordingly and improve investment portfolios. Furthermore, our findings also warn policymakers in emerging markets facing financial problems to pay special attention to the stock market in macroeconomic planning so as not to cause a crisis and, ultimately, capital flight. According to the results of this study, it can be recommended that in emerging economies such as Iran, which are currently facing declining GDP and a sharp rise in unemployment, the central bank must reduce interest rates so that companies can borrow at a lower cost and create new jobs. Therefore, as the production process in the country improves, companies can make more profit. Additionally, as new jobs increase, the unemployment rate decreases, and, ultimately, the levels of well-being and purchasing power of the people increase. Eventually, the findings of this study also advise companies operating in developed markets to consider macroeconomic market conditions in their cooperation agreements with foreign companies, in addition to identifying the characteristics and potentials of the company, so that they can avoid unexpected financial events.

When conducting any research, there are some restrictions on the researcher, and this research is no exception. One of the limitations of this study is the lack of use of regression at the company level (time series regression) due to the short time series of each company. Therefore, in the coming years, if we have the necessary information to conduct similar research over a longer period of time, this research will be recommended to be done using time series regression at the level of each company. Furthermore, given that the time period of the present study in Iran coincides with a financial crisis caused by sanctions, and that the sample companies may be different in terms of size, organizational structure, and type of products, generalization of our findings should be made with caution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., A.A., H.T., M.K., and G.Z.; methodology, M.M., A.A., H.T., and M.K.; resources, M.M., A.A., H.T., and G.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., A.A., H.T., M.K., and G.Z.; formal analysis, H.T., A.A., and M.M., writing—review and editing, H.T., M.M., A.A., and G.Z.; visualization, H.T., A.A., M.M., G.Z., and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, J.B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Corporate tax avoidance and stock price crash risk: Firm-level analysis. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 100, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A.P.; Marcus, A.J.; Tehranian, H. Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHodarahmi, B.; Foroughnejad, H.; Sharifi, M.; Talebi, A. The impact of information asymmetry on the future stock price crash risk of listed companies in the Tehran stock exchange. J. Asset Manag. Financ. 2016, 41, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Zhang, L. Accounting conservatism and stock price crash risk: Firm-level evidence. Contemp. Account. Res. 2016, 33, 412–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T. Corporate social responsibility and stock price crash risk. Manag. Financ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. CEO overconfidence and stock price crash risk. Contemp. Account. Res. 2016, 33, 1720–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Ren, H. Financial constraints and future stock price crash risk. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zolotoy, L. Stock liquidity and stock price crash risk. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2017, 52, 1605–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Corporate Financing and Stock Price Crash Risk; The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, V.A.; Lee, E.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, C. Corporate debt maturity and stock price crash risk. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2018, 24, 451–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Yu, S. Employee stock ownership plan and stock price crash risk. Front. Bus. Res. China 2019, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Equity incentives and crash risk in China’s a-share market. Asia-Pac. J. Risk Insur. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K. Corporate governance and stock price crash risk. Acad. Account. Financ. Stud. J. 2019, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Callen, J.L.; Fang, X. Religion and stock price crash risk. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2015, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cai, G. Religion and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. China J. Account. Res. 2016, 9, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Xia, C.; Chan, K.C. Social trust and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 46, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J. Media sentiment, institutional investors and probability of stock price crash: Evidence from Chinese stock markets. Account. Financ. 2017, 57, 1635–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, L. Individualism and stock price crash risk. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 1208–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harymawan, I.; Lam, B.; Nasih, M.; Rumayya, R. Political connections and stock price crash risk: Empirical evidence from the fall of Suharto. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, J. Investor trading behaviour and stock price crash risk. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 24, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, Y. Does investor sentiment affect stock price crash risk? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 27, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, Z. The impact of product market competition on stock price crash risk. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhei, M.; Khazaei, S.; Tarighi, H. Tax Avoidance and Corporate Risk: Evidence from a Market Facing Economic Sanction Country. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Salehi, M.; Tarighi, H.; Saravani, M. Audit adjustments and corporate financing: Evidence from Iran. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X. Economic policy uncertainty and stock price crash risk. Account. Financ. 2019, 58, 1291–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Myers, S.C. R2 around the world: New theory and new tests. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 79, 257–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Hasan, M.M.; Jiang, H. Stock price crash risk: Review of the empirical literature. Account. Financ. 2018, 58, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Tarighi, H.; Sahebkar, H. The impact of auditor conservatism on accruals and going concern opinion: Iranian angle. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Tarighi, H.; Safdari, S. The relation between corporate governance mechanisms, executive compensation and audit fees. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Stein, J.C. Differences of opinion, short-sales constraints, and market crashes. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2003, 16, 487–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R.; Rajgopal, S. The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2005, 40, 3–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S.P.; Shu, S.; Wysocki, P.D. Do managers withhold bad news? J. Account. Res. 2009, 47, 241–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hong, H.; Stein, J.C. Forecasting crashes: Trading volume, past returns, and conditional skewness in stock prices. J. Financ. Econ. 2001, 61, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, C. Economic policy uncertainty and stock price crash risk. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 51, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, A.A. The stochastic behavior of common stock variances: Value, leverage and interest rate effects. J. Financ. Econ. 1982, 10, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwert, G.W. Why does stock market volatility change over time? J. Financ. 1989, 44, 1115–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursoleiman, E.; Mansourfar, G.; Abidin, S. Financial leverage, debt maturity, future financing constraints and future investment. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O.J.; Watson, M.W. Bubbles, Rational Expectations and Financial Markets (No. w0945); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.Y.; Hentschel, L. No news is good news: An asymmetric model of changing volatility in stock returns. J. Financ. Econ. 1992, 31, 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, Q.; Schniederjans, M.J. Neural network earnings per share forecasting models: A comparative analysis of alternative methods. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 205–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozanic, Z.; Roulstone, D.T.; Van Buskirk, A. Management earnings forecasts and other forward-looking statements. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerard, J.B., Jr.; Mark, A. Earnings forecasts and revisions, price momentum, and fundamental data: Further explorations of financial anomalies. In Handbook of Financial Econometrics, Mathematics, Statistics, and Machine Learning; World Scientific Handbook in Financial Economics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, M.; Karimzadeh, M.; Paydarmanesh, N. The impact of Iran Central Bank’s sanction on Tehran Stock Exchange. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, V.; Schoenfeld, J.; Wellman, L. The effect of economic policy uncertainty on investor information asymmetry and management disclosures. J. Account. Econ. 2019, 67, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlevi, M. The Influence of Exchange Rate, Interest Rate and Inflation on Stock Price of LQ45 Index in Indonesia. In First International Conference on Administration Science (ICAS 2019); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghutla, C.; Sampath, T.; Vadivel, A. Stock prices, inflation, and output in India: An empirical analysis. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, E.; Ebrahimi, I. Does Financial and Economic Factors Influence Firm Value of Listed Company in Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE)? Econ. Stud. 2020, 29, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Goetzmann, W.N.; Brown, S.J.; Gruber, M.J.; Elton, E.J. Modern Portfolio Theory and Investment Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Miller, S.M. Currency Depreciation and Korean Stock Market Performance during the Asian Financial Crisis; University of Connecticut, Department of Economics: Storrs, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alikhani, H. Sanctioning Iran; I.B. Tauris: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, D.A.; Hayworth, S.C. Macroeconometrics of stock price fluctuations. Q. J. Bus. Econ. 1993, 32, 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, A.A.; Ghorashi, N. Trade Openness and the Behaviour of Stock Prices in Iran. Aust. Acad. Account. Financ. Rev. 2017, 1, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Guo, M. Local Economic Performance, Political Promotion, and Stock Price Crash Risk: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udegbunam, R.I.; Eriki, P.O. Inflation and stock price behaviour: Evidence from Nigerian stock market. J. Financ. Manag. Anal. 2001, 14, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.C.; Abdul Razak, S.H. The impact of nominal GDP and inflation on the financial performance of Islamic banks in Malaysia. J. Islamic Econ. Bank. Financ. 2015, 113, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Apergis, N.; Eleftheriou, S. Interest rates, inflation, and stock prices: The case of the Athens Stock Exchange. J. Policy Model. 2002, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.N. Inflation and stock index: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2019, 22, 408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Öner, C. Inflation: Prices on the Rise; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mazikana, A.T. The Effects of Inflation on Preparation of Financial Statements of the Retail Sector in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of OK Zimbabwe Limited (2018–2019). SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.M.; Awadalbari, A.A.A. Economic Growth and Unemployment in Sudan: An Empirical Analysis. Univ. Bakht Alruda Sci. J. 2014, 13, 342–355. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, C.; Liebens, P. The Relationship between GDP and Unemployment Rate in the US. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilo, B.M. Capital market and unemployment in Nigeria. Acta Univ. Danubius. Œconomica 2015, 11, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Tapa, N.; Tom, Z.; Lekoma, M.; Ebersohn, J.; Phiri, A. The unemployment-stock market relationship in South Africa: Evidence from symmetric and asymmetric cointegration models. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2017, 15, 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.F. Does the stock market really cause unemployment? A cross-country analysis. North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 44, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Parasnis, J. Discouraged workers in developed countries and added workers in developing countries? Unemployment rate and labour force participation. Econ. Model. 2014, 41, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallareddy, S.; Ogneva, M. Predicting restatements in macroeconomic indicators using accounting information. Account. Rev. 2017, 92, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.S.; Fok, R.C.W.; Liu, Y.A. Dynamic linkages between exchange rates and stock prices: Evidence from East Asian markets. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2007, 16, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, L.; Sun, L. Spillover effects between exchange rates and stock prices: Evidence from BRICS around the recent global financial crisis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2016, 36, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahir, A.M.; Mahat, F.; Ab Razak, N.H.; Bany-Ariffin, A.N. Revisiting the dynamic relationship between exchange rates and stock prices in BRICS countries: A wavelet analysis. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Saha, S. On the relation between exchange rates and stock prices: A non-linear ARDL approach and asymmetry analysis. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 42, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsva, P.; Lean, H.H. Multivariate causal relationship between stock prices and exchange rates in the middle east. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2017, 4, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehran Securities Exchange Technology Management, Co. Available online: http://en.tsetmc.com/Loader.aspx?ParTree=121C10 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran (CBI). Available online: https://cbi.ir/default_en.aspx (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Iran’s Profile on the Website of the World Bank (WB). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/iran (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Iran’s Profile on the Website of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/IRN (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Hu, G.; Wang, Y. Political connections and stock price crash risk. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C.F.; Schaffer, M.E. A General Approach to Testing for Autocorrelation; Boston College: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Savin, N.E.; White, K.J. The Durbin-Watson test for serial correlation with extreme sample sizes or many regressors. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1977, 1989–1996. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1914122 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- De Jager, P. Panel data techniques and accounting research. Meditari Res. J. Sch. Account. Sci. 2008, 16, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Fairbrother, M.; Jones, K. Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidheiny, K.; Basel, U. Panel data: Fixed and random effects. Short Guides Microeconom. 2011, 7, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, A. Firms’ fundamentals, macroeconomic variables and quarterly stock prices in the US. J. Econom. 2014, 183, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).