A Study on Sustainable Design for Indigo Dyeing Color in the Visual Aspect of Clothing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Indigo Dyeing

2.2. Sustainable Design

3. Materials and Methods

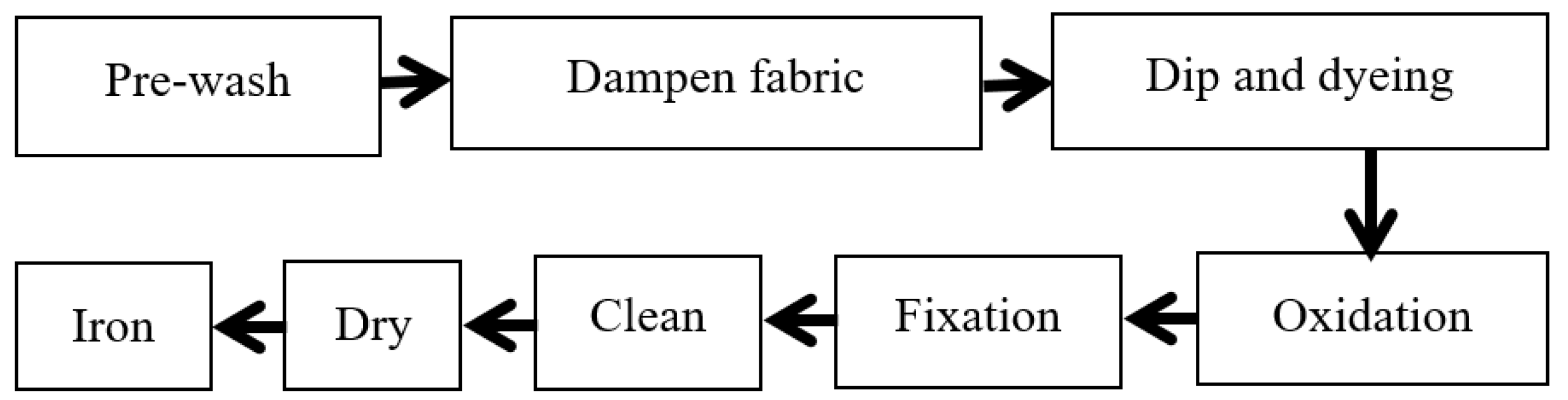

3.1. Indigo Dyeing Experiment and Procedure

3.2. Research Framework

3.3. Research Hypothesis

3.4. Data Collection

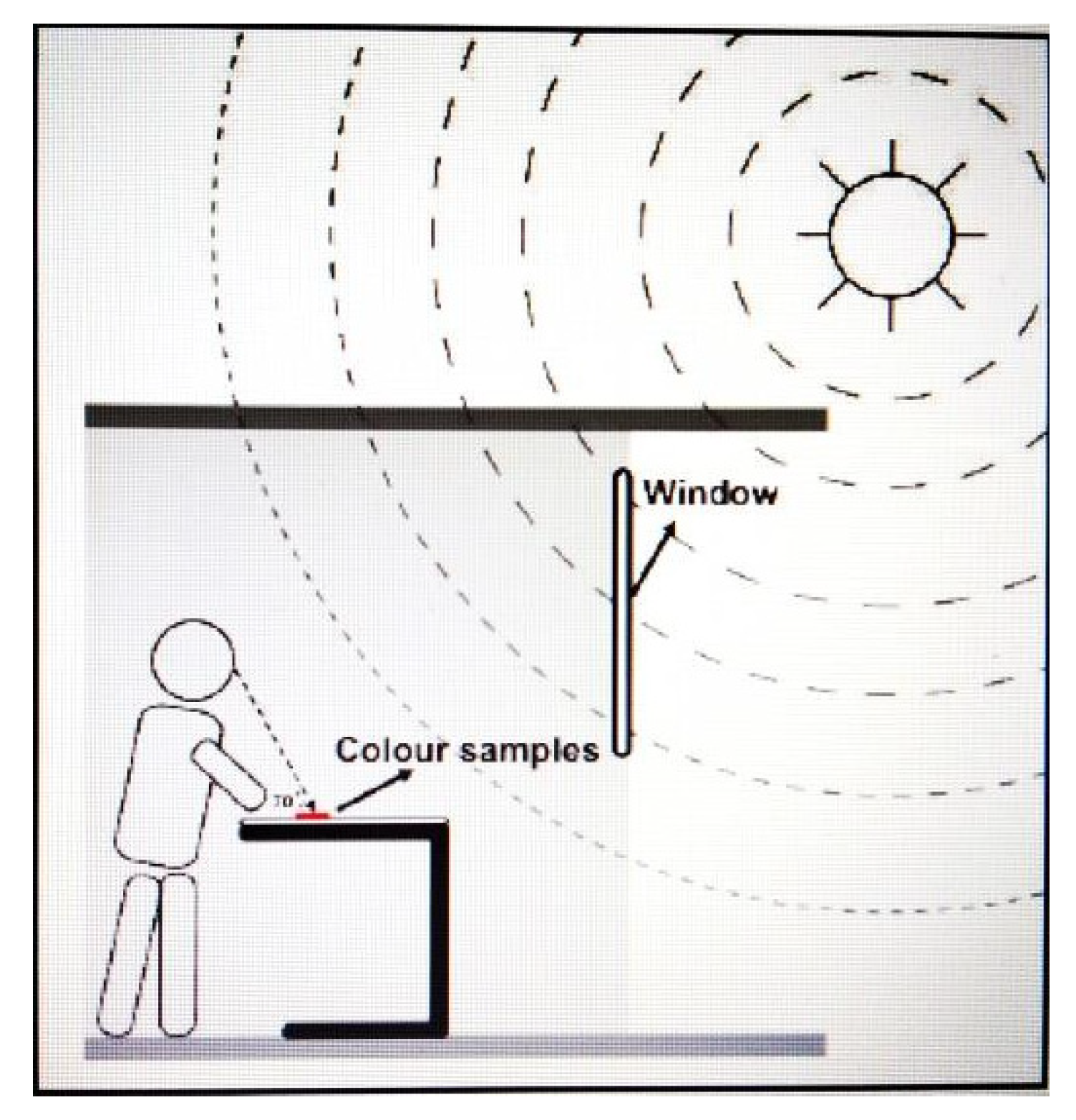

3.5. Process of Visual Experiment

3.6. Instrument

3.7. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Rosson, L.; Wang, X.; Byrne, N. Upcycling of waste textiles into regenerated cellulose fibres: Impact of pretreatments. J. Text. Inst. 2019, 111, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’cruz, A. Adding an eco-friendly colour to the world. Chem. World 2012, 10, 40–41. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrea_Sandra_Christine_Dcruz/publication/257033508_Insight_and_Outlook-Natural_Dyes/links/00b7d524db5de1c18e000000.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Kawahito, M.; Urakawa, H.; Ueda, M.; Kajiwara, K. Color in Cloth Dyed with Natural Indigo and Synthetic Indigo. Sen’i Gakkaishi 2002, 58, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GilPavas, E.; Correa-Sanchez, S. Assessment of the optimized treatment of indigo-polluted industrial textile wastewater by a sequential electrocoagulation-activated carbon adsorption process. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 36, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, P.O.; Adekunle, A.A.; Obidi, O.F.; Olukanni, O.D.; Govindwar, S.P. Degradation of indigo dye by a newly isolated yeast, Diutina rugosa from dye wastewater polluted soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4639–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Tan, X.; Bie, B.; Ma, H.; Yi, H. Practical and environment-friendly indirect electrochemical reduction of indigo and dyeing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4927–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.F. Sowing the seed of indigo dye: A survey of indigo dyeing projects organized by NTCRI. Taiwan Crafts 2014, 54, 24–29. Available online: https://mocfile.moc.gov.tw/ntcrihistory/ebook/978b6jnes_f.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Lin, C.M.; Lin, C.H.; Cheng, T.H. The application of indigo dyeing pattern design in clothing-take batik as example. J. Hwa Gang Text. 2017, 24, 66–71. Available online: http://www.jhgt.org.tw/pdf/jhgt-24.2(66-71)(2017-02).pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Chen, J.L. Indigo dyeing in Sanshia: A 10 years’ retrospect. Taiwan Crafts 2009, 34, 82–85. Available online: https://mocfile.moc.gov.tw/ntcrihistory/ebook/409ocOX_f.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Hsu, C.I.; Yen, H.Y.; Lin, R. Introducing co-learning and co-creating to revive local craftsmanship: An experimental study on indigo dyeing craftsmanship in Sanxia, Taiwan. J. Arts Humanit. 2018, 7, 68–78. Available online: https://www.theartsjournal.org/index.php/site/article/view/1519 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Lee, J.C. Dyeing art of Taiwan, living traces of our land: Itti-natural dye color research. Taiwan Crafts 2009, 70, 42–45. Available online: https://mocfile.moc.gov.tw/files/201809/b5fdf662-3979-4879-a000-1340c2b805ea.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Dharma Trading Co. How to Dye with Natural Indigo. 2015. Available online: https://www.dharmatrading.com/information/how-to-dye.html (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Ellis, C. Indigo Dyeing: Time and Patience. 2018. Available online: https://blog.ellistextiles.com/2018/01/22/indigo-dyeing-time-and-patience/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Wu, H.M. Indigo fashion: Zhuo Ming-bang’s Zhuo Ye Cottage. Taiwan Crafts 2013, 51, 56–59. Available online: https://mocfile.moc.gov.tw/ntcrihistory/ebook/42o6oE_f.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Wandemberg, J.C. Sustainable by Design; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1516901784. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, C. Paths to Sustainability: Creating Connections through Place-Based Indigenous Knowledge. Master’s Thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, S.; Mehra, R.; Head, E.E. Role of globalized approach for sustainability development in human life. People Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davies, N. Using Bacteria to Decolorize Textile Wastewater. AATCC Rev. 2017, 17, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future Report. 1987. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/energy-government-and-defense-magazines/united-nations-world-commission-environment-and-development-wced-our-common-future-report-1987 (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Robert, K.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What is Sustainable Development? Goals, Indicators, Values, and Practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chequer, F.M.D.; Oliveira, G.A.R.; Ferraz, E.R.A.; Cardoso, J.C.; Zanoni, M.V.B.; de Oliveira, D.P. Textile dyes: Dyeing process and environmental impact. In Eco-Friendly Textile Dyeing and Finishing; Gunay, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; pp. 151–176. ISBN 978-953-51-0892-4. Available online: https://books.google.com.tw/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=IGOfDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=ISBN:+978-953-51-0892-4&ots=zywn9ILcFW&sig=0d8Ruz3yKh4VR_bVMFweIB1qhmk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=ISBN%3A%20978-953-51-0892-4&f=false (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Dhanjal, N.I.K.; Mittu, B.; Chauhan, A.; Gupta, S. Biodegradation of Textile Dyes Using Fungal Isolates. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 6, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McLennan, J.F. The Philosophy of Sustainable Design, 1st ed.; Ecotone Publishing Company LLC: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–8. ISBN 0-9749033-0-2. Available online: https://books.google.com.tw/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=-Qjadh_0IeMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR15&dq=The+philosophy+of+sustainable+design&ots=UtrMG0LkjL&sig=9LAj5ocCujQvTcaUmwT9uAf09eM&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=The%20philosophy%20of%20sustainable%20design&f=false (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Blizzard, J.L.; Klotz, L.E. A framework for sustainable whole systems design. Des. Stud. 2012, 33, 456–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, T.; Turcanu, A.; Ganglberger, E.; Geissler, S. Natural dyes in modern textile dyehouses—How to combine experiences of two centuries to meet the demands of the future? J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Dhinakaran, M. Extraction and application of natural dyes from orange peel and lemon peel on cotton fabrics. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 237–238. Available online: https://www.irjet.net/archives/V4/i5/IRJET-V4I541.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- MIAH, M.; Telegin, F.; Rahman, M. Eco-friendly dyeing of wool fabric using natural dye extracted from onion’s outer shell by using water and organic solvents. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2016, 3, 450–467. Available online: https://www.irjet.net/archives/V3/i9/IRJET-V3I983.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Adeel, S.; Rehman, F.-U.; Rafi, S.; Zia, K.M.; Zuber, M. Environmentally Friendly Plant-Based Natural Dyes: Extraction Methodology and Applications. Plant Hum. Health 2019, 2, 383–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektaş, I.; Karaman, Ş.; Dıraz, E.; Çelik, M. The role of natural indigo dye in alleviation of genotoxicity of sodium dithionite as a reducing agent. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučković, N.; Kodrić, M.; Nikodijević, M.; Đorđević, D. Modeling of the linen fabric dyeing after previous preparation. Adv. Technol. 2018, 7, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R. Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. Nat. Sci. 2012, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.; Matias, J.; Catalão, J. Analysis of the use of biomass as an energy alternative for the Portuguese textile dyeing industry. Energy 2015, 84, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Bodake, U.; Pathade, G. Extraction of natural dye from chili (capsicum annum) for textile coloration. Univers. J. Environ. Res. Technol. 2011, 1, 58–63. Available online: http://www.environmentaljournal.org/1-1/ujert-1-1-8.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Malacara, D. Color vision and colorimetry: Theory and applications. Color Res. Appl. 2002, 28, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.M.; Lee, W.Y. Colour preference model for elder and younger groups. J. Int. Color Ass. 2017, 18, 33–42. Available online: http://www.aic-colour.org/journal.htm (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behavior: A comparative study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 335–341. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/47708/2/Paper_IJCS_%2528final_version_180411%2529-1.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Mundkur, S.; Dedhia, E. Supply chain for second-hand clothes in mumbai. Text. Value Chain 2012, 1, 57–58. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/S_Mundkur/publication/259452417_’Waste_Management_and_Supply_Chain_for_Second-hand_Clothes_in_Mumbai’_a_research_article_published_in_Textile_Value_Chain_Volume_1_Issue_3_October-December_2012_ISSN_No_2278-8972_Pp_57-58/links/555062d108ae956a5d24bd13.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Arshad, K.; Skrifvars, M.; Vivod, V.; Valh, J.; Vončina, B. Biodegradation of Natural Textile Materials in Soil. Tekstilec 2014, 57, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Cluver, B. Biodegradation and mildew resistance of naturally colored cottons. Text. Res. J. 2010, 80, 2188–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, M.; Davis, K.; Wolf, D.; Gbur, E. Soil burial effects on biodegradation and properties of three cellulosic fabrics. Am. Assoc. Text. Chem. Colorists Rev. 2011, 11, 53–57. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287919000_Soil_burial_fefects_on_biodegradation_and_properties_of_Three_cellulosic_fabrics (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Rahman, O.; Koszewska, M. A study of consumer choice between sustainable and non-sustainable apparel cues in Poland. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | Making Process | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Growing indigo | Growing indigo plants. | Raw materials come from natural plants. |

| 2. Picking indigo | Harvesting indigo plants in both June to July and November to December mornings every year. | Indigo plants picked by manual labor. |

| 3. Soak | Cutting stems and cleaning them, and then soaking them in water for about one and a half to two days until indimuslin appears. | Only use water. |

| 4. Oxidation in a vat | Removing rotted leaves and adding some lime water, mixing and oxidizing indimuslin with lime by a pump and water circulating system. It will become foamy; after two or three hours, the foam disappears, meaning that the indimuslin has been oxidized. | Using lime and electricity. |

| 5. Indigo mud | Two or three days later, the infant dye needs to be whipped and some water needs to be added to settle it again. Two or three days later, the dye needs to be whipped to obtain the indigo mud. | Waste liquid could be used for irrigation. |

| 6. Indigo dyeing | Put the indigo mud in a vat, and then dip dye fabrics. | Indigo dyeing is ready for use. |

| Steps | Making Process | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-wash | Pre-wash fabrics going to be dyed | Using manual labor, water and gas. |

| 2. Selection of dyeing techniques | Indigo dyeing techniques include plain dyeing, shibori, board indigo dyeing, stencil dyeing, batik, and discharge dyeing. | _ |

| 3. Design and make | Design patterns and techniques, and then planning procedure and process. | Making patterns by hand. |

| 4. Dampen fabric | Dampen fabrics in order to obtain uniform dyeing. | Preparing water. |

| 5. Dyeing | There are two methods: dip dyeing and deep dyeing. | Manual operation. |

| 6. Oxidation | Expose to air for oxidation. | Manual operation. |

| 7. Repeat dip and oxidation | Repeat dip and oxidation until fabrics appear expected color. | Manual operation. |

| 8. Remove resist-dyeing tools | Remove tying thread, rope, popsicle sticks or wax. | Manual removing. |

| 9. Fixation | Use water as a thinner for white vinegar and dip for 5 min. | Using white vinegar and water. |

| 10. Clean | Wash with water to clean. | Only water. |

| 11. Dry | Dry the fabrics. | Dry by airing. |

| 12. Iron | Iron the fabrics. | Using electricity. |

| Color | Recyclable | Less-Polluting | Resource-Saving | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| 1 |  | 3.95 (.92) | 4.22 (.72) | 3.97 (.79) |

| 2 |  | 3.90 (.80) | 4.06 (.77) | 3.83 (.73) |

| 3 |  | 3.63 (.92) | 3.86 (.89) | 3.61 (.84) |

| 4 |  | 3.70 (.91) | 3.77 (.97) | 3.47 (.93) |

| 5 |  | 3.41 (1.05) | 3.51 (1.09) | 3.28 (1.00) |

| 6 |  | 3.30 (1.14) | 3.39 (1.18) | 3.19 (1.08) |

| 7 |  | 3.01 (1.24) | 3.10 (1.32) | 2.73 (1.19) |

| 8 |  | 2.90 (1.28) | 2.97 (1.33) | 2.58 (1.21) |

| 9 |  | 2.71 (1.34) | 2.79 (1.41) | 2.48 (1.30) |

| F | 42.837 | 56.233 | 60.464 | |

| p | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | |

| Post-Hoc | 1, 2 > 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 3 > 6, 7, 8, 9 4 > 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 5, 6 > 7, 8, 9 7, 8 > 9 | 1 > 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 2 > 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 3, 4 > 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 5, 6 > 7, 8, 9 7 > 9 | 1, 2 > 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 3 > 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 4 > 6, 7, 8, 9 5, 6 > 7, 8, 9 | |

| p Trend | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lai, C.-C.; Chang, C.-E. A Study on Sustainable Design for Indigo Dyeing Color in the Visual Aspect of Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073686

Lai C-C, Chang C-E. A Study on Sustainable Design for Indigo Dyeing Color in the Visual Aspect of Clothing. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073686

Chicago/Turabian StyleLai, Chih-Chun, and Ching-Erh Chang. 2021. "A Study on Sustainable Design for Indigo Dyeing Color in the Visual Aspect of Clothing" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073686

APA StyleLai, C.-C., & Chang, C.-E. (2021). A Study on Sustainable Design for Indigo Dyeing Color in the Visual Aspect of Clothing. Sustainability, 13(7), 3686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073686