1. Introduction

In the evolving global economy, the digital revolution now serves as a key factor in transforming both international economic structures and operational business frameworks [

1]. Recent developments in information technology, particularly the rapid expansion of e-commerce, big data analytics, and cloud computing platforms, have greatly changed the way firms operate, create value, and compete in the market [

2]. Within this broader context, the field of international trade has also undergone a profound digital transformation, and one of the most notable recent developments has been the rapid rise of cross-border e-commerce (CBEC). CBEC, as an innovative international commerce model, enables companies in different nations or regions to directly engage in online transactions, payment settlements, and cross-border logistical delivery using the Internet and digital platforms [

3]. It is not only a manifestation of the deep integration between the digital and real economies but also a key driver of global trade growth and an important engine for restructuring global value chains.

Compared with traditional international trade models, one of the most distinctive features of CBEC is its ability to overcome the constraints of geography and physical distance. Digital technologies have provided firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with an unprecedented ability to reach global markets. Through e-commerce platforms, firms can operate around the clock, employ online advertising and social media for targeted marketing, and take advantage of increasingly sophisticated global logistics networks to simplify product distribution [

4]. This transformation has not only lowered the barriers to international trade but also significantly facilitated the free flow of capital, information, and goods worldwide [

2]. The application of emerging technologies such as blockchain has further enhanced the transparency and efficiency of cross-border e-commerce supply chains [

5]. Therefore, cross-border e-commerce is no longer merely a channel innovation but has evolved into a disruptive force profoundly reshaping firms’ strategies, organisational structures, and operating models [

6].

In the increasingly challenging and uncertain global market environment, innovation has become a key driver of firms’ long-term competitiveness and sustainable development. However, firms’ innovation activities are not random or unconstrained; rather, they are bounded by their existing knowledge bases, technological capabilities, and cognitive frameworks—collectively referred to as the “innovation boundary” [

7,

8]. The innovation boundary can be understood as the scope within which a firm engages in innovative exploration, particularly reflecting its ability and willingness to extend into new technological or knowledge domains. Limiting business operations to existing technological trajectories and knowledge domains through incremental or exploitative innovation may reduce short-term risks, but in the long run, it tends to cause technological lock-in and core capability rigidity, leaving firms vulnerable to disruptive technological shocks. In contrast, continuously breaking through and expanding the innovation boundary to engage in exploratory innovation across new technological domains is crucial for firms to discover new growth opportunities, build dynamic capabilities, and enhance environmental adaptability and organisational resilience [

9,

10].

However, expanding the innovation boundary represents a major challenge for firms. It requires companies to overcome cognitive limitations and organisational inertia, and to effectively acquire, integrate, and leverage heterogeneous external knowledge and resources. This issue lies at the heart of the organisational theory literature on “boundary spanning,” which examines how firms connect and exchange knowledge across internal and external boundaries [

11]. A growing body of research has shown that effectively spanning knowledge boundaries within and across organisations is a key driver of innovation [

12,

13]. Firms therefore need to establish connections with diverse external actors—such as customers, suppliers, competitors, and research institutions—to access new knowledge, ideas, and technologies [

14]. However, many firms face an “innovation dilemma” in practice, struggling to balance the refinement of existing business strategies with the exploration of new opportunities. This dilemma often results in the rigidification of innovation boundaries [

15].

Here a key question arises: can cross-border e-commerce, as a business practice deeply embedded in the ongoing waves of globalisation and digitalisation, help firms overcome their internal knowledge and technological barriers and effectively expand their innovation boundaries? Although a considerable body of literature has examined the effects of CBEC on firms’ export performance [

16], supply-chain management [

17], and market-entry strategies [

18], the internal link between CBEC and the expansion of firms’ innovation boundaries—particularly the underlying mechanisms through which CBEC affects such expansion—has not yet been adequately theorised or rigorously tested empirically.

China, as the world’s largest e-commerce market and a major manufacturing power, has witnessed particularly rapid growth in CBEC, which has attracted significant attention and policy support from the national government. Since 2015, the Chinese government has successively established a series of Cross-Border E-Commerce Comprehensive Pilot Zones (CBECPZs). These pilot zones are designed to promote institutional, managerial, and service innovations that create a more facilitative and regulated policy environment for the development of cross-border e-commerce. Specific measures include simplifying customs clearance procedures through a “single window” system, offering tax incentives, and improving logistics and payment infrastructures. The implementation of these policies has substantially reduced the institutional and operational barriers faced by firms engaging in cross-border e-commerce within the pilot zones, thereby providing an excellent quasi-natural experimental setting for observing the deeper impacts of CBEC on firm behaviour.

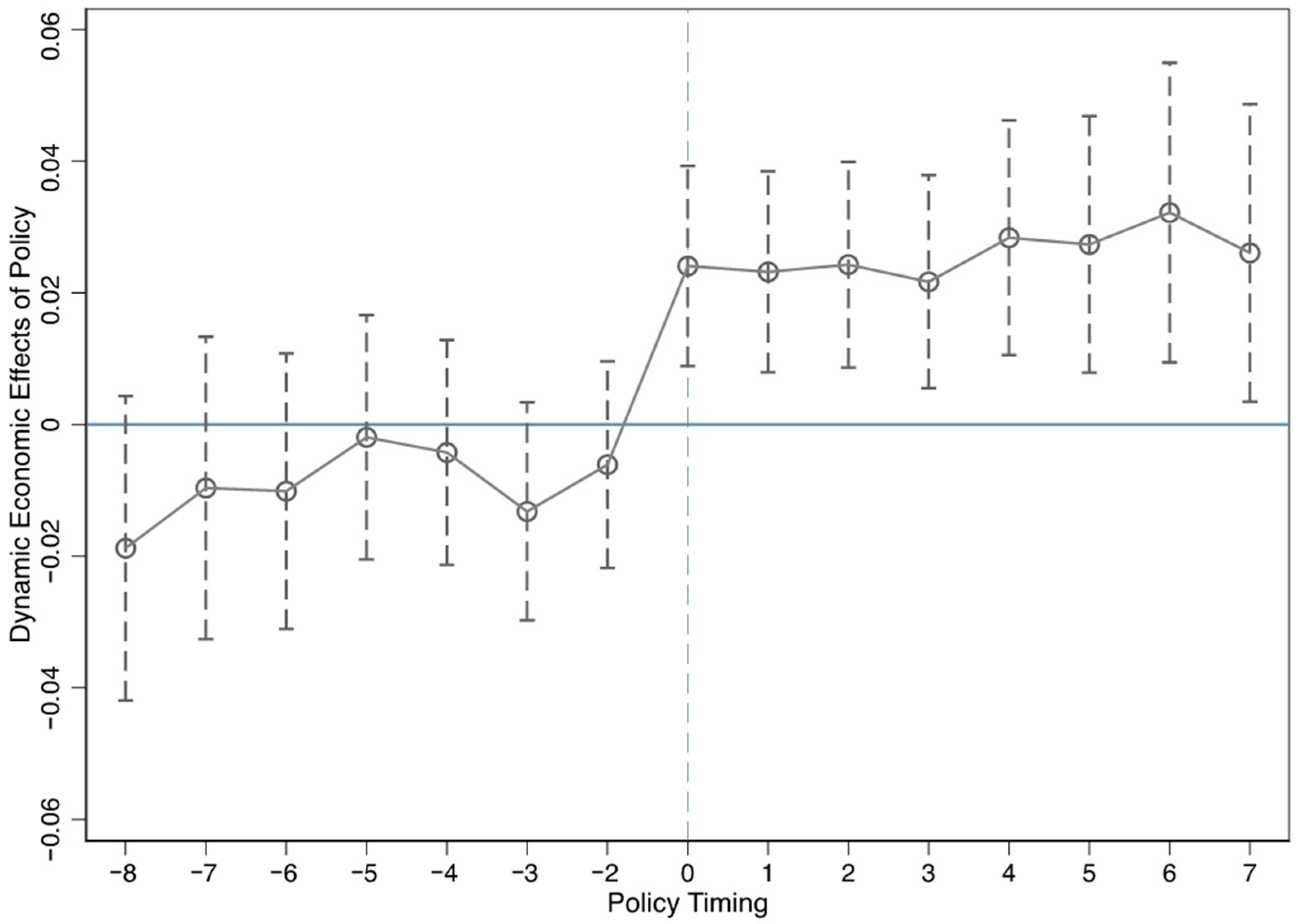

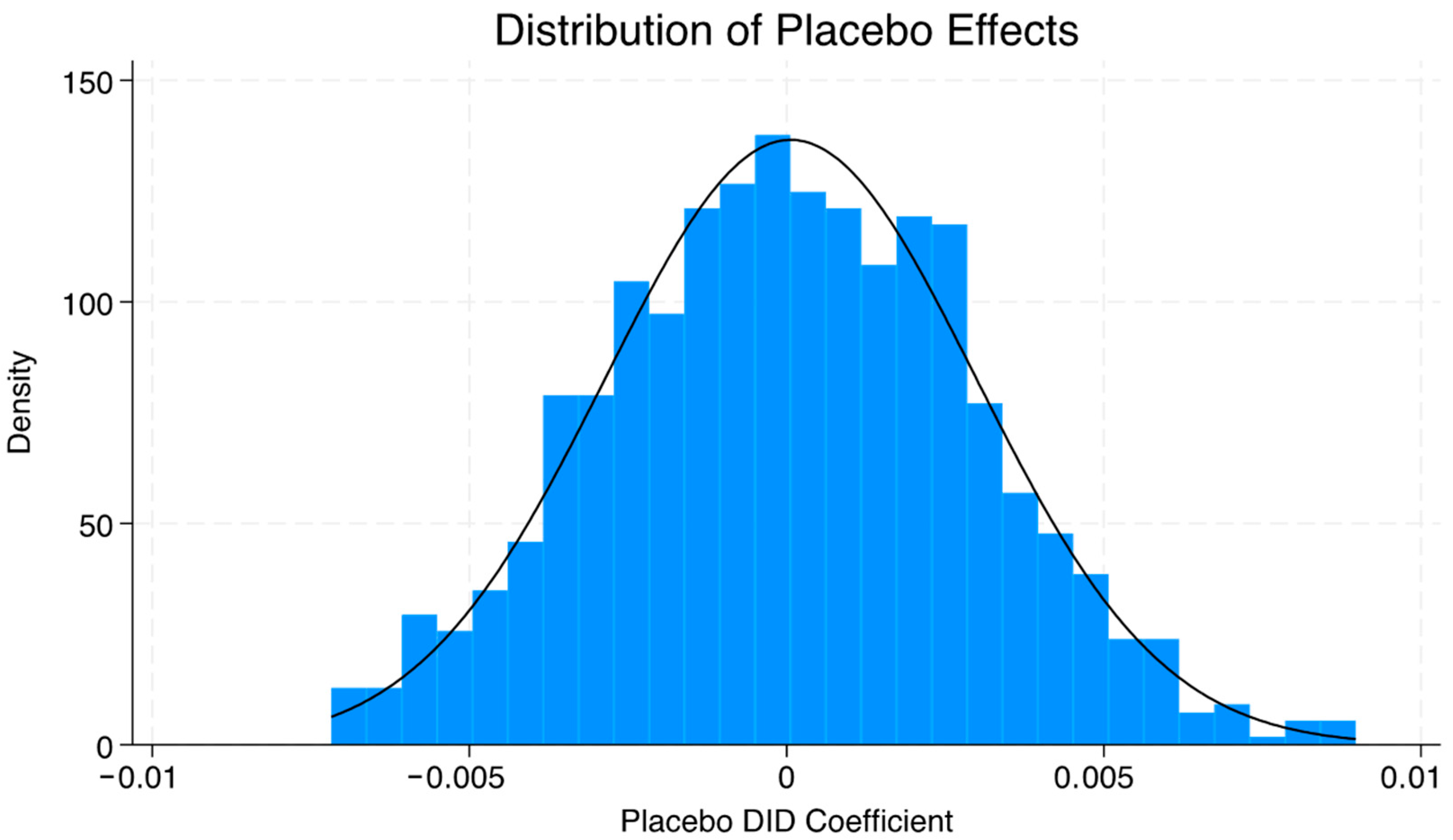

This paper, using the establishment of CBECPZs in China as a quasi-natural experiment, employs panel data from Chinese A-share listed firms spanning 2010 to 2023 to construct a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model, thereby examining the policy’s impact through a rigorous empirical framework. The study is designed to tackle three core issues: (1) whether the establishment of CBEC Pilot Zones has substantially stimulated innovation activities among firms located within these zones; (2) if there is a positive impact, what fundamental mechanisms enable CBEC to drive firms’ innovation; and (3) whether this promotive effect, if confirmed, demonstrates heterogeneity across different firms and regions.

This study aims to make several contributions to the existing literature by systematically addressing the aforementioned questions. First, at the theoretical level, this study extends the research perspective on CBEC beyond traditional trade performance indicators—such as export volume and export resilience—to the deeper dimension of firms’ innovative behaviour, particularly the expansion of innovation boundaries. This not only enriches the literature on the economic consequences of CBEC but also offers a new theoretical explanation for how international trade influences firm innovation in the digital economy era. Moreover, the study contributes to the literature on innovation boundaries by identifying a new driving force—policy-driven digital trade practices—as an important external mechanism that enables firms to overcome knowledge barriers and pursue exploratory innovation. Second, at the empirical level, by exploiting the quasi-natural experiment of the Comprehensive Cross-Border E-commerce Pilot Zones and employing a multi-period DID model, this study provides a more accurate identification of the causal effect of CBEC development on firms’ innovation-boundary expansion. The findings demonstrate robust causal efficacy and reveal substantial policy implications, while overcoming potential issues of sample selection bias and reverse causality that may have affected previous studies. Third, at the practical level, the findings of this study provide important implications for both government policymaking and corporate strategy. For policymakers, the results offer empirical evidence for assessing the innovation effects of CBEC-related policies, suggesting that promoting CBEC development is not only a way to stabilise foreign trade but also an effective means of stimulating firms’ innovation vitality and facilitating industrial upgrading. For business managers, this study reveals that the strategic value of CBEC extends far beyond the expansion of sales channels. Firms should leverage CBEC as a strategic platform for gaining global market insights, learning cutting-edge technologies, and upgrading human capital, thereby systematically enhancing their innovation capability and long-term competitiveness.