The Ineffectiveness of “Volume Guarantee” Mode in Live-Streaming: A Nash Bargaining Analysis with Social Network Effects and Traffic Costs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ⮚

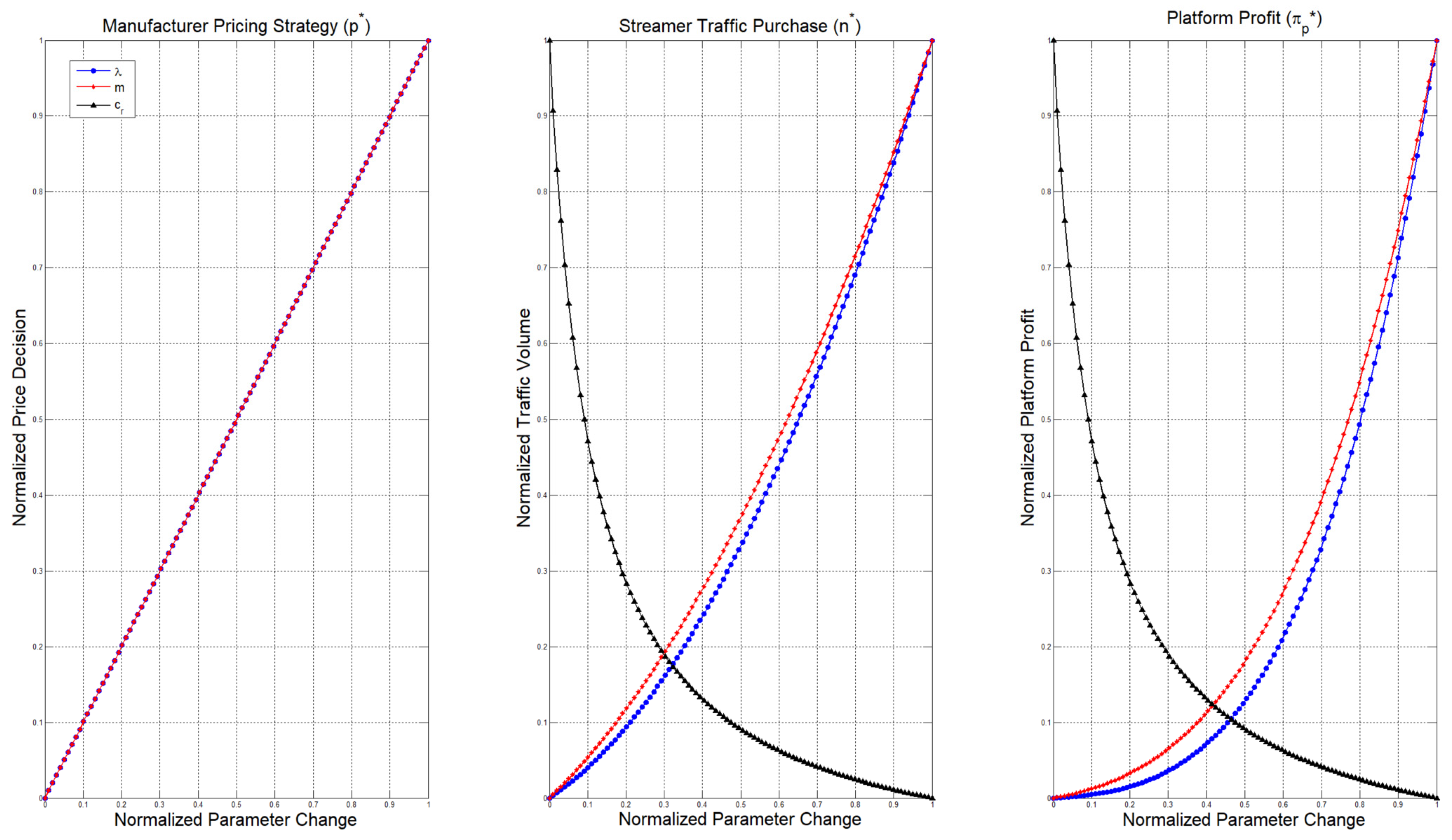

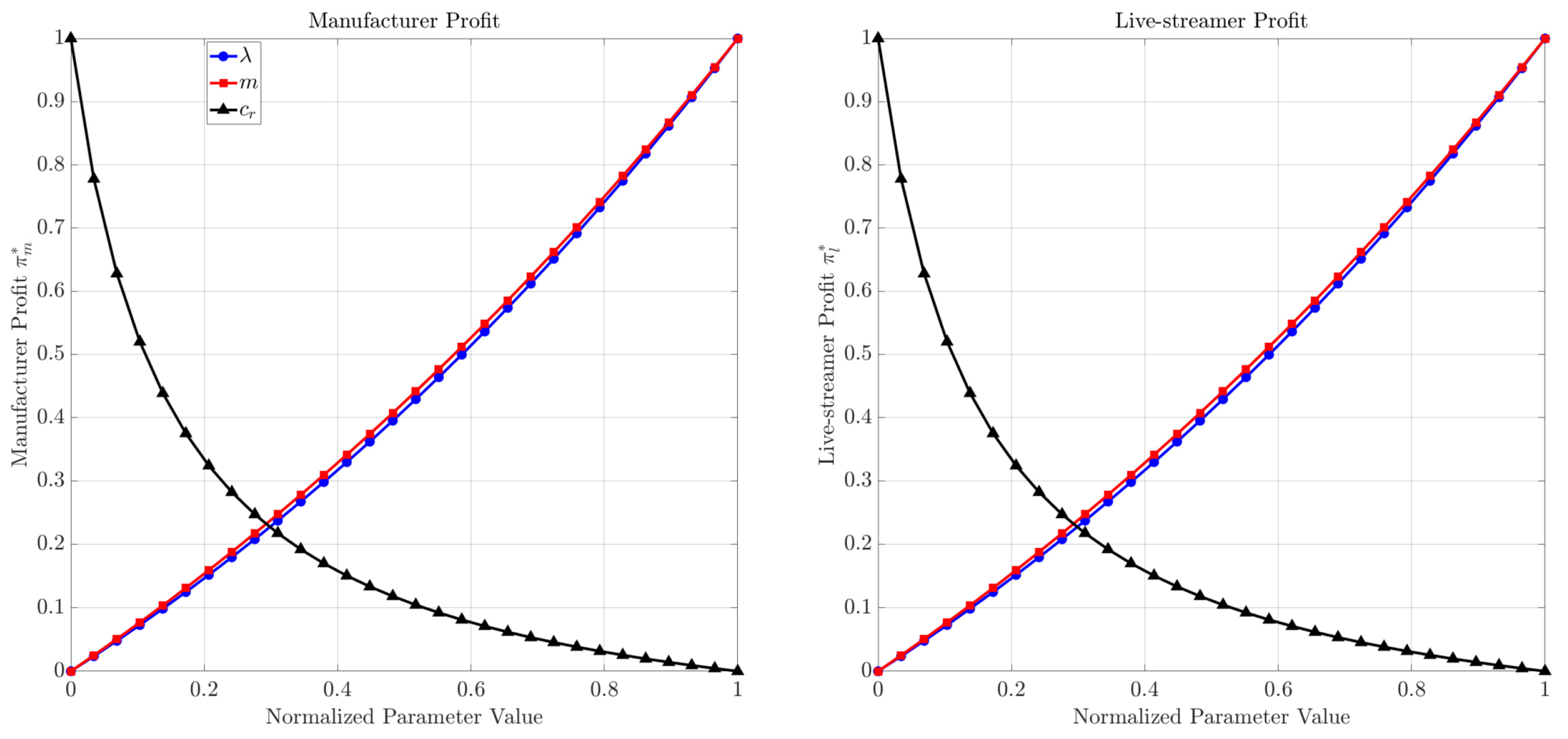

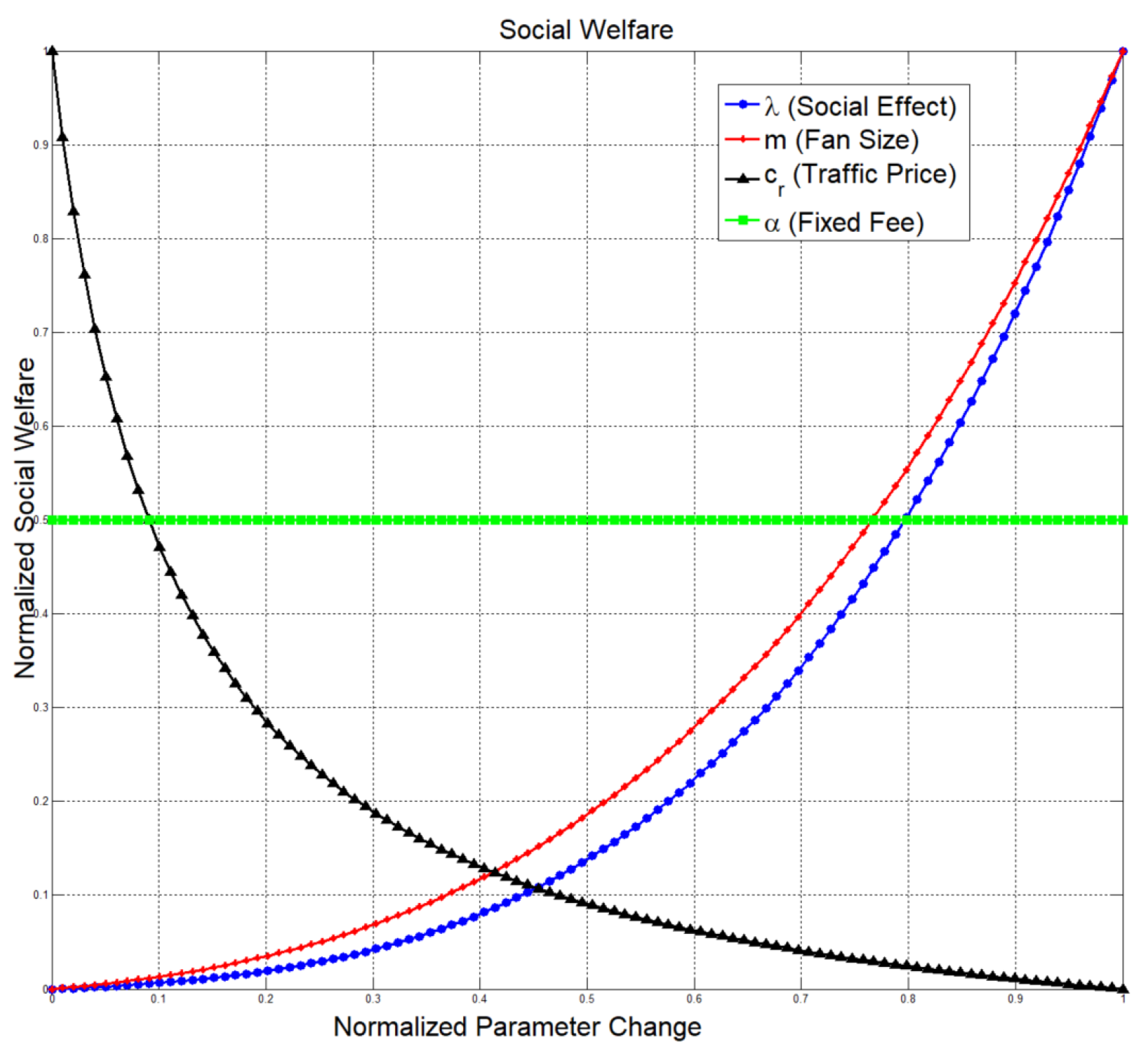

- (1) How do supply chain decisions, revenue, and social welfare depend on factors such as public traffic costs, social network effects, and fanbase-size of live-streamers?

- ⮚

- (2) How efficient is the “volume guarantee” mode, and is it better than the “general” mode?

- ⮚

- (3) How does unequal status (bargaining power) affect supply chain decision-making, profit, and social welfare?

- First, we demonstrate that under a fair profit-sharing scheme, manufacturers and streamers can achieve supply chain coordination without relying on external “volume guarantee” contracts. This outcome is unique to environments where long-term cooperation and fairness are valued, as the Nash bargaining solution endogenously aligns individual incentives with the collective optimum.

- Furthermore, our analysis highlights the critical role of the streamer’s social network. The size of the fanbase not only directly boosts demand but also amplifies the effectiveness of platform-based traffic, creating a multiplier effect on overall profits and social welfare.

- Additionally, we uncover a fundamental decoupling within the supply chain coordination mechanism: while the bargaining power determines the distribution of profits, it does not distort the operational decisions (pricing and traffic acquisition) that maximize the total supply chain value. This finding reveals that under Nash bargaining fairness, the pursuit of individual interest naturally aligns with collective efficiency, making complex “volume guarantee” contracts redundant for coordination.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Network Effect in Live-Streaming

2.2. Supply Chain Decision-Making in Live-Streaming

2.3. Cooperation Mode Selection in Live-Streaming

2.4. Research Gap and Our Contribution

- (1)

- (2)

- Research on supply chain decision-making has extensively analyzed factors like platform fees [16], manufacturer pricing/quality [5,17], and streamer effort/commission [7]. However, a key limitation is the frequent assumption of unequal power structures or the omission of explicit mechanisms to ensure fairness in the bargaining process between manufacturers and streamers. The inherent power imbalance is acknowledged as a problem [4,5], but solutions promoting equitable cooperation are underexplored.

- (3)

- Studies on cooperation mode selection, particularly regarding commission structures like the “volume guarantee” mode, reveal inconsistencies and practical challenges. For instance, conclusions about manufacturer preferences for influencers differ between Qi et al. [6] and Ye et al. [4], highlighting the difficulty in achieving fair decision-making. Existing research offers limited theoretical guidance for designing contracts that foster equitable cooperation between manufacturers and streamers, which is crucial for mitigating issues like data fraud and contract disputes [12].

3. Base Model

3.1. Methodological Foundation: The Nash Bargaining Framework

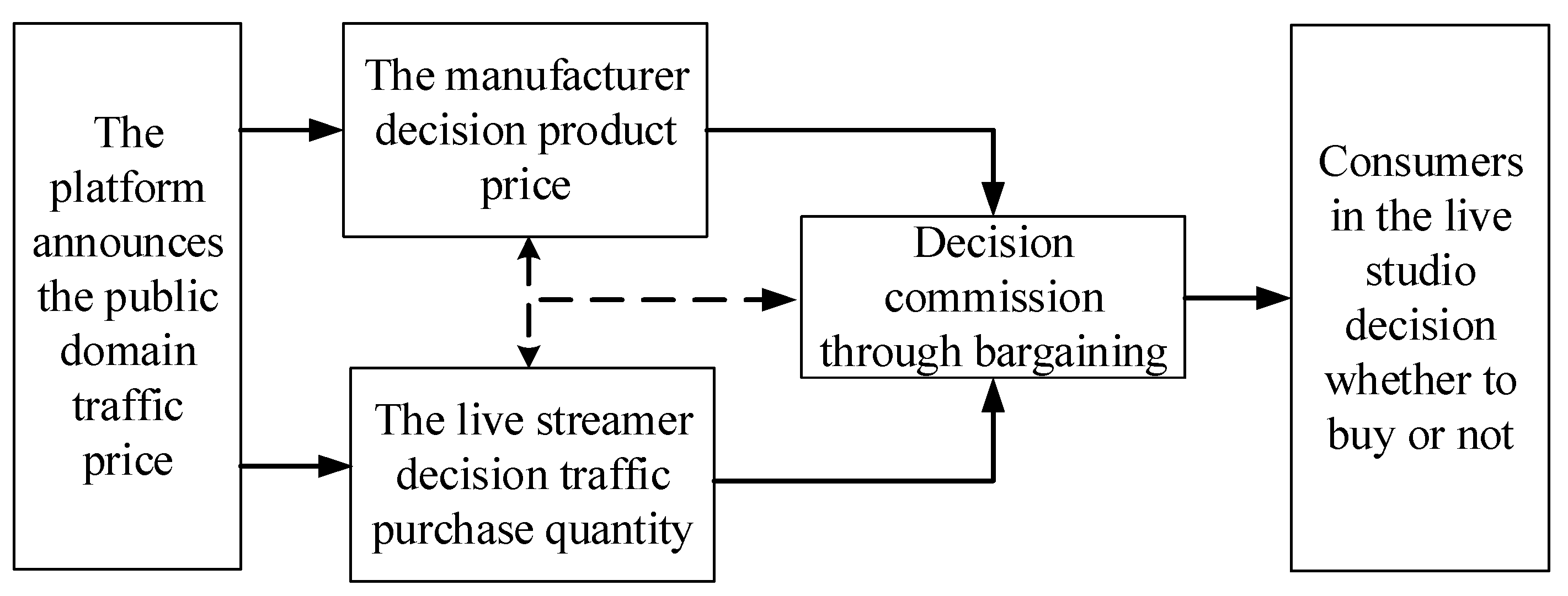

3.2. Game Players and Decision Order

3.3. Research Assumptions

- (1)

- For the consumer

- (2)

- For the manufacturer

- (3)

- For the live-streamer

3.4. Commission Mode

4. Model Solving and Equilibrium Analysis

4.1. Under General Mode

4.2. Under the Volume Guarantee Mode

4.2.1. Joint Decision

4.2.2. Live-Streamer Commitment

4.2.3. Manufacturer Decision

5. The Expansion: Bargaining Power and Social Welfare

5.1. Heterogeneous Bargaining Power

5.2. Social Welfare and Platform

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Main Findings

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; He, N.; Miles, I. Live Commerce Platforms: A New Paradigm for E-Commerce Platform Economy. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Lim, W.M.; Cheah, J.H.; Lim, X.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Live Streaming Commerce: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2025, 65, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Jiang, F.; Li, Q.; Yu, D.; Tan, Y. Harnessing Empathy: The Power of Emotional Resonance in Live Streaming Sales and the Moderating Magic of Product Type. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Ji, L.; Ning, Y.; Li, Y. Influencer selection and strategic analysis for live streaming selling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wan, M. Choice of product quality in supply chain of live-streaming e-commerce under different power structures. Aust. J. Manag. 2025, 50, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, A.; Sethi, S.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J. Top or Regular Influencer? Contracting in Live-Streaming Platform Selling. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2022, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Gui, L.; Lu, Y. Managing Sales via Livestream Commerce: Implications of Price Negotiation and Consumer Price Search. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2024. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/10591478231224930 (accessed on 26 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cao, B. Understanding the Impacts of Top-Tier Streamer De-Emphasizing in Live Streaming E-Commerce: A Social Evolution Game Perspective. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 81524–81536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Bai, R.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, M.; Qiang, J. Offline Detection of Violations in Chinese E-commerce Live Streaming Content. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 112785–112796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Peng, L.; Chen, T.; Cong, G. Regulation strategy for behavioral integrity of live streamers: From the perspective of the platform based on evolutionary game in China. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Proportional incentive contracts in live streaming commerce supply chain based on target sales volume. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 25, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B. The Supply Chain Management of Live Streaming E-Commerce. Adv. Econ. Manag. Polit. Sci. 2025, 147, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, J. How short video marketing influences purchase intention in social commerce: The role of users’ persona perception, shared values, and individual-level factors. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chaudhry, S.S. Enhancing consumer engagement in e-commerce live streaming via relational bonds. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, J.; Nie, T. Social influence and channel competition in the live-streaming market. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025, 344, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, S. Optimal decisions and coordination of live streaming selling under revenue-sharing contracts. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Fu, T.; Choi, T.M.; Kumar, A.; Tan, K.H. Price and quality strategy in live streaming e-commerce with consumers’ social interaction and celebrity sales agents. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 4063–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, V.; Jerath, K.; Zhang, Z.J. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2259–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, N.; Ji, X. Reselling or agency selling? The strategic role of live streaming commerce in distribution contract selection. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 983–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fan, W.; Zhou, M. Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Chen, K.J.; Lin, J.S. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Wang, M.; Shamu, Y. The impact of network social presence on live streaming viewers’ social support willingness: A moderated mediation model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Fu, X. Understanding the purchase intention in live streaming from the perspective of social image. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sujood; Rehman, A.; Kareem, S.; Al Rousan, R. Livestreaming in events: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2025, 16, 168–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Zhao, W. The impact of live-streaming interactivity on live-streaming sales mode based on game-theoretic analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Jin, Y. Brands’ livestream selling with influencers’ converting fans into consumers. Omega 2025, 131, 103195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zheng, C.; Hao, C. Optimal platform sales mode in live streaming commerce supply chains. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 1017–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yin, Z.; Liu, Y. The value of horizontal cooperation in online retail channels. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 39, 100897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Wang, Z. Live-streaming selling modes on a retail platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 173, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Fu, T.; Li, S. Optimal selling format considering price discount strategy in live-streaming commerce. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 309, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Yang, L. Resale or agency sale? Equilibrium analysis on the role of live streaming selling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, X.; Chen, Y. Optimal manufacturer strategy for live-stream selling and product quality. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 64, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, S.X. Commit on effort or sales? Value of commitment in live-streaming e-commerce. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2024, 33, 2241–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, W. Strategic decision making in live streaming e-commerce through tripartite evolutionary game analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tao, Z.; Liang, L.; Gou, Q. An analysis of salary mechanisms in the sharing economy: The interaction between streamers and unions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 214, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Wei, W. The impacts of market size and data-driven marketing on the sales mode selection in an Internet platform based supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tan, D.; Wang, G.; Wei, H.; Wu, J. Retailer’s vertical integration strategies under different business modes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhou, X.; Lev, B. Core, shapley value, nucleolus and nash bargaining solution: A survey of recent developments and applications in operations management. Omega 2022, 110, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Stream | Representative Literature | Focus of Existing Studies | Research Gaps | Contributions of This Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Network Effects in Live-streaming | Hu and Chaudhry [14]; Kim et al. [1]; Peng et al. [15] | Consumer engagement drivers; Platform paradigm amplified by network effects. | Lack of integration with bargaining fairness and joint supply chain decisions. | Integration of social network effects into a Nash bargaining framework to analyze joint decisions and enhance efficiency. |

| Supply Chain Decision-Making in Live-streaming | H. Liu and S. Liu [16]; Ji et al. [17]; Lin et al. [7]; Zhang et al. [5] | Platform fees; Pricing/quality decisions; Streamer effort/commission; Power structures. | Omission of explicit fairness mechanisms; Underexplored solutions for equitable cooperation. | Introduction of Nash bargaining to endogenize fairness. Demonstration of efficiency-equity separation (power affects distribution, not operations). |

| Cooperation Mode Selection in Live-streaming | Abhishek et al. [18]; Wang et al. [19]; Zhang and Xu [11] | Comparison of resale vs. agency selling; “Volume guarantee” mode analysis. | Inconsistent findings on commission structures; Lack of theoretical guidance for equitable contracts. | Proof of the ineffectiveness of the “volume guarantee” mode under fair bargaining, providing a theoretical explanation for market observations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Lu, J. The Ineffectiveness of “Volume Guarantee” Mode in Live-Streaming: A Nash Bargaining Analysis with Social Network Effects and Traffic Costs. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040314

Li H, Lu J. The Ineffectiveness of “Volume Guarantee” Mode in Live-Streaming: A Nash Bargaining Analysis with Social Network Effects and Traffic Costs. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040314

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, He, and Juan Lu. 2025. "The Ineffectiveness of “Volume Guarantee” Mode in Live-Streaming: A Nash Bargaining Analysis with Social Network Effects and Traffic Costs" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040314

APA StyleLi, H., & Lu, J. (2025). The Ineffectiveness of “Volume Guarantee” Mode in Live-Streaming: A Nash Bargaining Analysis with Social Network Effects and Traffic Costs. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040314