1. Introduction

Short-form video platforms (e.g., TikTok, Douyin) have shifted advertising from discrete, stand-alone spots to in-feed, swipeable stimuli that compete with an endless stream of entertainment and user-generated content [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In these feeds, ads appear alongside organic videos and are skippable within seconds, placing a premium on immediate comprehension and rapid persuasion. Short-form video is therefore not merely “shorter television” but a distinct persuasion context marked by constrained processing time, rapid cue turnover, and algorithmic curation. Theoretical accounts of limited attentional resources are central in such contexts. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) and the Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing (LC4MP) formalize how finite capacity is allocated to audiovisual material and how extraneous demands impair message processing [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

This paper examines a creative choice pervasive on short-form platforms yet under-specified in advertising research: a “one face, many roles” casting strategy in which a single performer rapidly portrays multiple characters, contrasted with a conventional multi-actor execution. We propose that consolidating roles in one recognizable performer reduces extraneous cognitive load by minimizing identity tracking and role segmentation within seconds, thereby improving downstream persuasion relative to multi-actor formats in short-form settings [

6,

7,

9]. We further argue that this processing relief facilitates authenticity inferences. When messages are easier to parse, people experience processing fluency—a metacognitive signal that shapes judgments of truth and genuineness [

10,

11,

12]. In branding, perceived authenticity—the sense that a brand is true to its essence and values—is a robust antecedent of favorable evaluations and intentions [

13,

14]. Accordingly, we model a chain in which casting reduces cognitive load, which elevates authenticity, which in turn enhances purchase-relevant outcomes. In parallel, lower cognitive load should also improve evaluations of the creator’s account/channel that hosts the ad, yielding a simple mediation from casting to account evaluation via load.

Boundary conditions are expected at both the viewer and brand levels. Individuals higher in Need for Closure (NFC)—a preference for swift, unambiguous resolution—should benefit disproportionately from simplified identity tracking and thus exhibit larger gains from single-actor executions [

15,

16]. Brand-type fit should also matter: playful or “exciting” brands may find a rapid, multi-persona performance congruent with their identity, whereas competence-oriented brands may be better served by traditional multi-actor signals of professionalism [

13,

17,

18]. For clarity, we conceptualize brand type as a boundary condition on the overall casting effect on account impression and purchase intention, rather than as a moderator of each mediation path.

We test these ideas in a multi-study program preceded by a large pretest to calibrate “multi-actor” complexity and followed by four experiments spanning online, offline, field, and text-based settings (total N = 4513). Across studies, we manipulate casting, measure cognitive load and authenticity with established scales, examine viewer- and brand-level moderators (NFC; brand type), and evaluate outcomes for both the ad host (account impression) and the advertised brand (purchase intention). We also rule out an alternative process account by testing whether perceived cost constraint and sympathy form a viable sequential pathway from casting to persuasion; they do not, and the single-actor advantage persists when budget cues are made explicit. Together, the evidence supports a dual-path account in which processing efficiency in micro-narratives is pivotal for short-form persuasion and authenticity emerges as a downstream evaluation rather than a mere stylistic cue.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. We review literature on cognitive load in mediated message processing and on brand authenticity to formalize hypotheses. We then detail the pretest and four experiments, present results, and conclude with theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and avenues for future research.

3. Hypothesis Formulation and Research Framework

In long-form or standard television advertising, including cinematic spots and extended online videos, a larger and more diverse cast often fosters credibility, realism, and dramatic depth [

18,

31]. Those formats typically afford viewers minutes to learn who each person is and how their actions advance the plot. By contrast, TikTok-style short-form ads compress brand stories into 15–60 s, so every additional face must be encoded in a fraction of the time available; as a result, extra identities compete for limited processing resources and attention [

6,

7]. Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) formalizes this constraint by positing a severely bounded working memory; when an execution adds elements that must be attended to, individuated, and held in mind, comprehension and persuasion suffer [

6,

7]. The Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing (LC4MP) extends the same logic to audiovisual messages, arguing that structural features and additional cues draw on a single, finite pool of encoding and storage resources [

8,

9]. Advertising studies on visual complexity converge on this point: denser arrays with more focal elements impose higher processing burden and depress effectiveness unless complexity is actively managed [

24,

25].

Face perception research suggests a concrete mechanism through which casting multiplies cognitive requirements. Humans individuate faces largely via configural processing; once a single identity is encoded, subsequent sightings of that same face demand less effortful individuation [

26]. A short-form execution in which one performer rapidly shifts costumes, postures, and vocal registers permits viewers to anchor each persona change to an already-built facial schema, rather than initiating fresh identification routines for unfamiliar actors. Taken together, these perspectives imply that a single-actor/multi-role format should compress the number of distinct identity cues that must be encoded, enhance perceptual fluency via repeated face-schema activation, and redirect spared capacity from “who’s who?” indexing to message comprehension. Accordingly,

H1. Relative to a multi-actor cast, deploying one performer in multiple roles will reduce viewers’ perceived cognitive load in short-video advertising.

If the one-actor format reduces extraneous load as posited in H1, then the immediate evaluative consequences should extend beyond comprehension to how viewers judge the source that “hosts” the message in a social-video feed. Dual-process theories hold that speeded, divided-attention contexts bias audiences toward heuristic processing, so cues that increase processing ease acquire greater persuasive weight [

27,

28]. When a message is fluently processed, people experience positive affect and a “feels-right” sensation that facilitates favorable judgments [

10,

11,

12]. LC4MP further links higher load to adverse psychophysiological responses, which can spill over into less favorable content evaluations [

9]. In social video, attitudes formed during processing often attach to the perceived communicator—frequently the creator’s account rather than a corporate channel—via source attribution and related parasocial mechanisms [

35,

36,

37]. Lower load also frees attentional bandwidth for relational signals (e.g., eye contact, micro-timing of humor, narrative pacing) that support parasocial affinity, thereby improving account-level impressions [

38,

39]. Consequently, reducing cognitive effort should translate into more favorable evaluations of the account that curates the ad. Accordingly,

H2. Lower cognitive load will improve viewers’ evaluations of the short-video account that hosts the advertisement.

The same reduction in processing difficulty has implications for perceived brand authenticity, which we define as the extent to which a brand is seen as true to its essence and values [

13,

14]. A large literature shows that metacognitive ease shapes truth and genuineness judgments; information that is easier to process often feels more plausible and “real” [

10,

11]. In short-form advertising, a single-actor/multi-role execution decreases identity-tracking demands and reduces the need to re-segment roles across cuts, so parsing the narrative feels effortless. That sense of fluency is then (mis)attributed to brand sincerity and transparency rather than to executional simplicity per se, consistent with authenticity perceptions that are sensitive to cues of craft, integrity, and continuity [

13,

32,

40]. Importantly, this reasoning does not claim that authenticity is merely fluency; rather, it posits a causal ordering under short-form constraints in which lower extraneous load enables clearer meaning construction, which in turn supports authenticity inferences when the performance reads as personally invested and “nothing-to-hide.” Accordingly,

H3. Lower cognitive load will enhance consumers’ perceptions of brand authenticity in short-video advertising.

Brand authenticity, once formed, is a robust antecedent of consequential outcomes, including identification, trust, and willingness to buy or pay a premium [

13,

14]. In short-form feeds, users make rapid go/no-go decisions about whether to act on an impression while scrolling; authenticity therefore functions as a high-leverage summary signal that converts fleeting attention into intention. If the one-actor format reduces load and thereby elevates authenticity perceptions as argued in H1 and H3, then higher authenticity should directly lift purchase intention. Accordingly,

H4. Higher perceived brand authenticity will increase consumers’ purchase intention toward the advertised brand.

The preceding arguments specify a processing-first logic in which casting structure primarily influences extraneous cognitive load, and this early constraint shapes evaluative judgments under short-form, feed-embedded viewing [

6,

7,

8,

9,

28]. Building directly on that ordering, we now formalize the mediational and moderating relations without re-stating prior rationale.

Given that a single-actor/multi-role execution reduces identity-tracking demands, the resulting ease of processing should translate into more favorable impressions of the hosting account—a source-side evaluation formed in the stream where ads are encountered [

35,

36].

H5a (simple mediation). Casting strategy → Cognitive load → Account evaluation.

Separately, the same reduction in cognitive effort should enable authenticity inferences about the brand and thereby lift purchase intention, consistent with authenticity’s role as a high-leverage evaluative signal in rapid-scroll contexts [

13,

14].

H5b (chain mediation). Casting strategy → Cognitive load → Brand authenticity → Purchase intention.

The five hypotheses above jointly specify the sequential logic that undergirds our framework. Casting format affects extraneous cognitive load first, because individuating one face across roles is simpler than tracking multiple unfamiliar actors in seconds. Reduced load then pre-conditions evaluative processing in two ways: it improves account evaluations through fluency-driven affect and attention to relational cues (H2), and it enables authenticity inferences about the brand by making the message feel clear, candid, and personally delivered (H3). Authenticity, once elevated, translates into stronger purchase intention (H4). This ordering is consistent with CLT and LC4MP’s emphasis on capacity constraints as precursors to higher-order judgments, with dual-process models that assign greater weight to fluency under time pressure, and with authenticity research that links perceived sincerity to behavioral intentions [

6,

8,

9,

14,

28]. It also coheres with evidence that adding novel sources within micro-narratives raises processing costs and attenuates persuasion—precisely the pattern we would expect if cognitive economy is the initiating step in the chain [

4].

Individuals differ in their tolerance for ambiguity and desire for definitive answers. Need for Closure (NFC) captures this motive and predicts stronger preference for clear, quickly resolvable information structures [

15,

41]. In a seconds-long ad, a multi-actor cast proliferates identity cues and prolongs uncertainty about “who is who,” while a single-actor format collapses those cues into a consistent facial schema. Under ELM/HSM conditions where time pressure biases heuristic processing, high-NFC viewers are especially sensitive to ambiguity and thus benefit more from format choices that deliver immediate coherence [

27,

28]. Combining these perspectives with CLT/LC4MP, the predicted interaction is straightforward: the single-actor format should yield a larger reduction in cognitive load among high-NFC audiences because it resolves identity ambiguity at the point where resources are scarcest [

6,

8,

9]. Accordingly,

H6. Need for Closure moderates the effect of casting on cognitive load: the load reduction produced by a single-actor/multi-role format (vs. multi-actor) is greater for high-NFC than for low-NFC individuals.

This moderation at the processing node implies downstream heterogeneity in the two mediated paths formalized above: stronger improvements in account evaluation (via load → source liking) and purchase intention (via load → authenticity → intention) for high-NFC segments, which prefer order and closure under temporal pressure.

Short-form viewers hold schematic expectations about how different brands “ought” to communicate. Exciting/entertaining brands are granted broader latitude for playful, persona-switching performances; serious/competence-oriented brands are expected to project reliability through more formal cues [

13,

14,

17,

18]. A single-actor format naturally foregrounds expressive craft and quick-fire role contrast—an esthetic that fits approach-oriented, fun brand identities—while a multi-actor layout more readily signals institutional competence and external validation in professional categories. Within our processing-first framework, this means that the same reduction in load can amplify authenticity when the performance feels brand-congruent (for entertaining brands), yet be offset by a schema violation that dampens authenticity when the performance feels flippant relative to category norms (for serious brands). Consequently, casting should interact with brand type on both consumer purchase intentions and account-level impressions. Accordingly,

H7. Brand type moderates the effect of a one-actor/multi-role casting strategy on (a) purchase intention and (b) positive account impressions: the strategy is more effective for entertaining/exciting brands than for serious/competence-oriented brands.

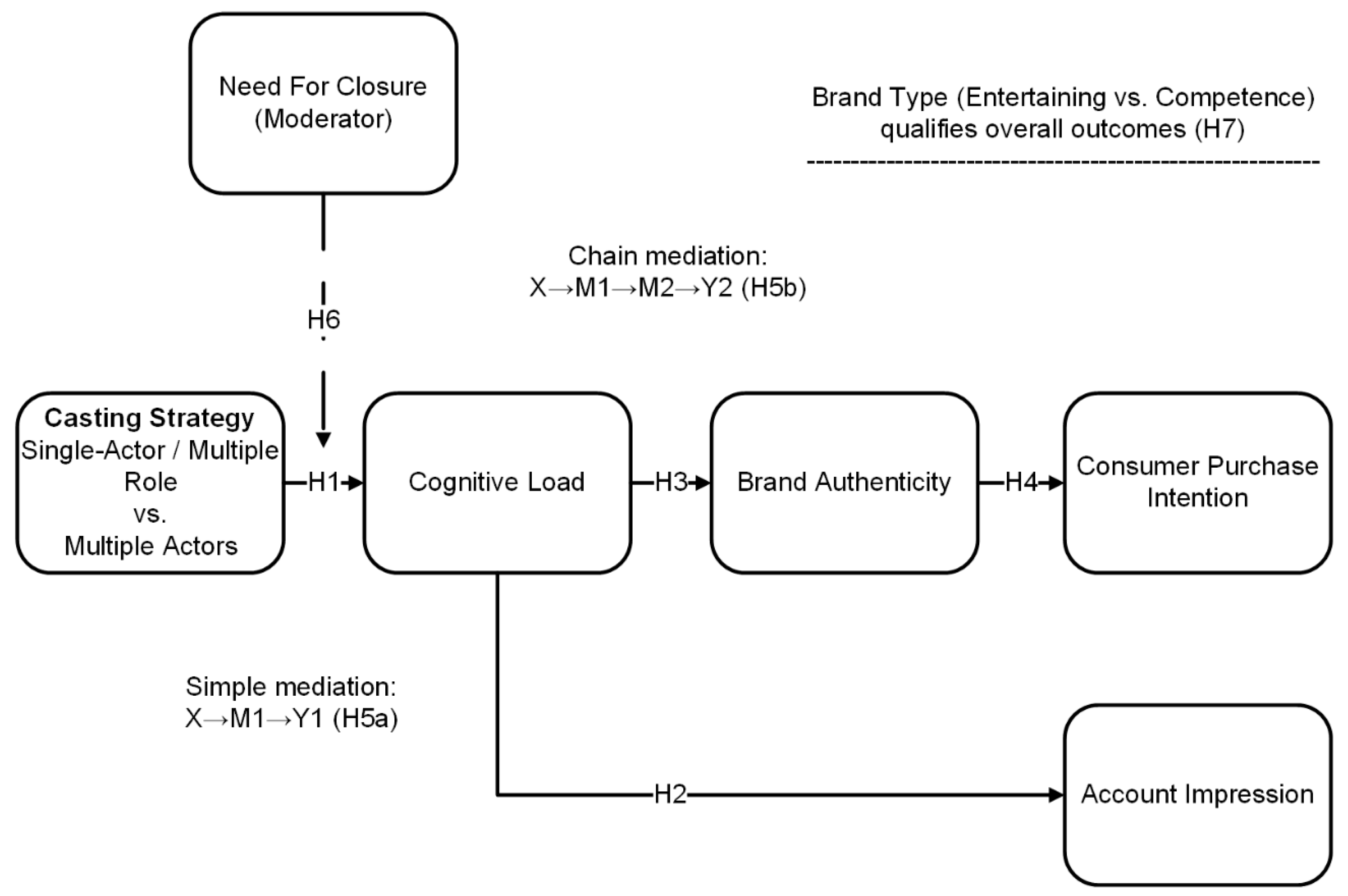

Figure 1 (Conceptual Framework) synthesizes Hypotheses 1–7 into a unified structural model. The diagram positions casting strategy (one-actor/multi-role vs. multi-actor) as the exogenous driver. Its primary effect proceeds through cognitive load—the central processing-efficiency mechanism identified in H1—and branches into two theoretically distinct consequence streams.

Collectively, the framework integrates information-processing theory with brand-personality and individual-difference perspectives, offering a parsimonious yet comprehensive account of how creative casting decisions in short-video advertising propagate through cognitive, affective, and contextual mechanisms to shape both brand-centric and account-centric outcomes.

5. General Discussion

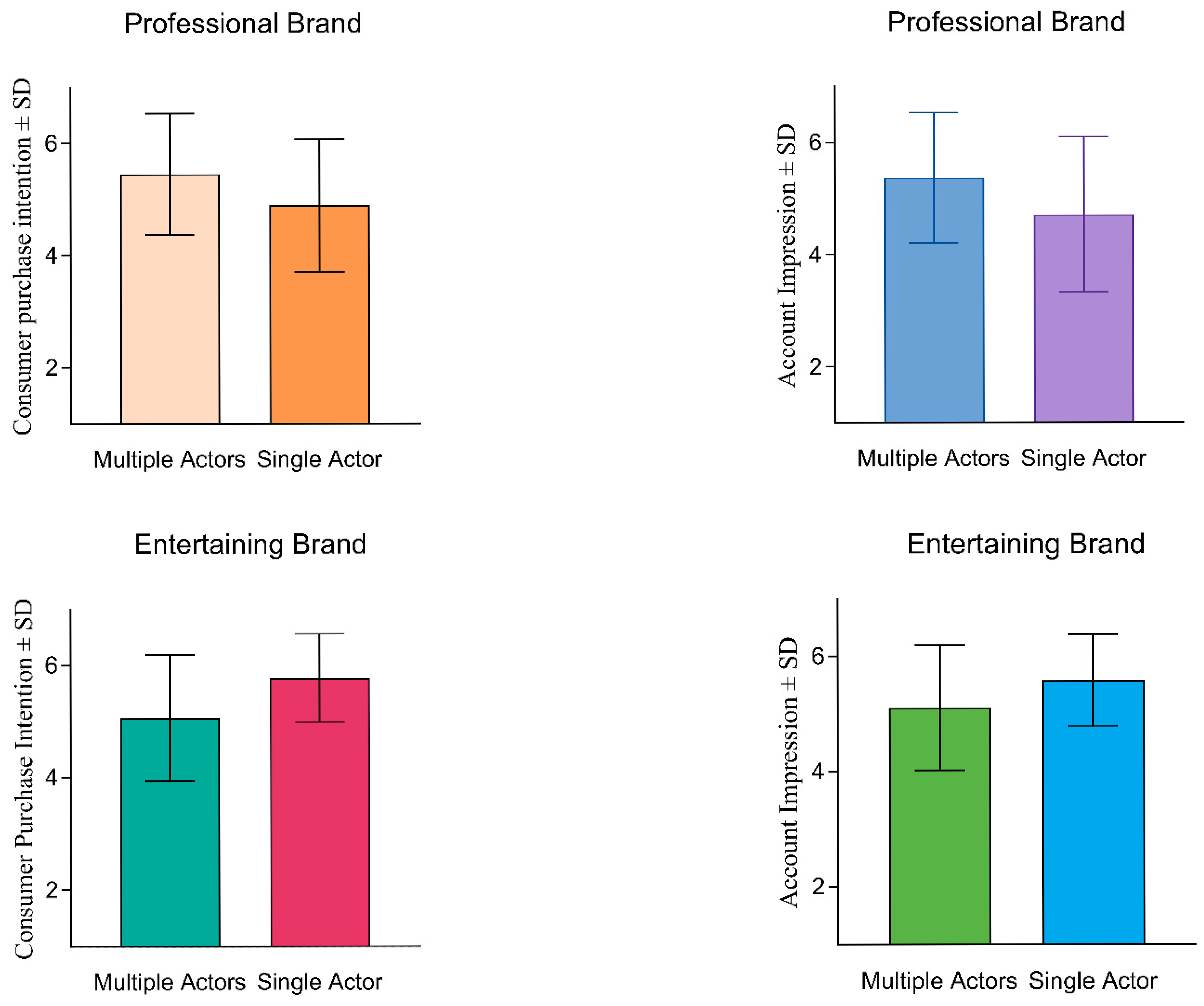

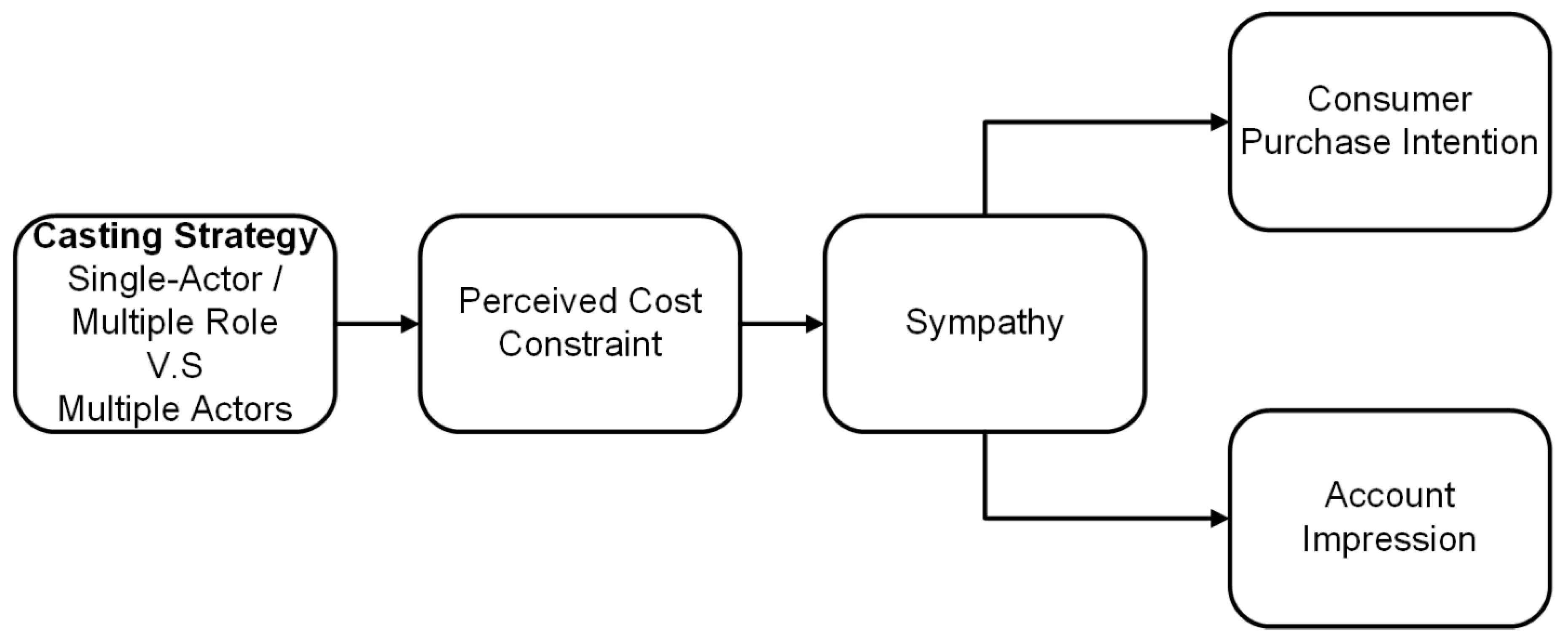

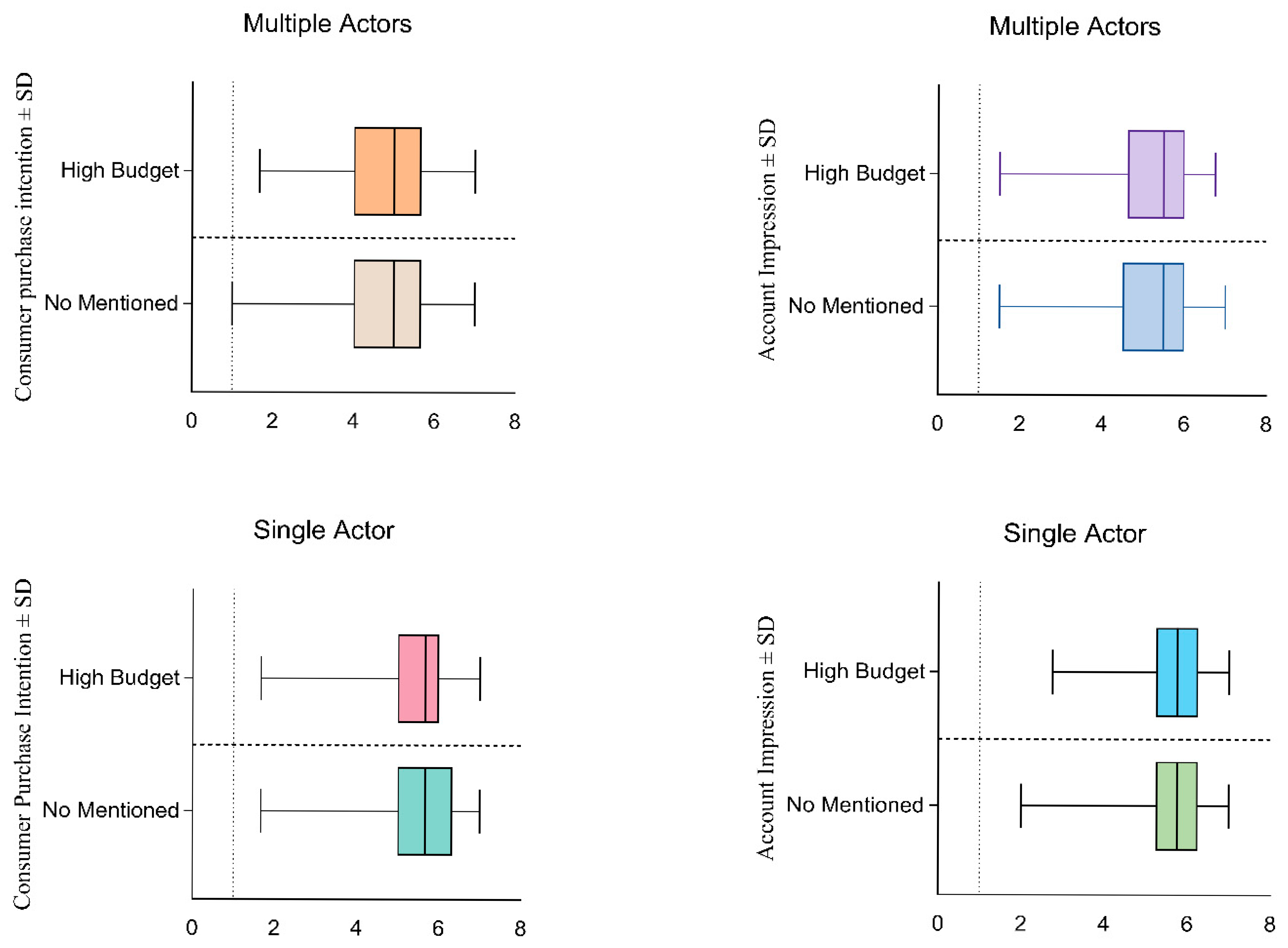

Across four complementary experiments spanning online video (1a), offline replication (1b), a field setting (2), and text-only scripts that strip away surface cues (3–4), we find convergent evidence that a single-performer/multiple-roles casting strategy improves short-video ad effectiveness relative to conventional multi-actor executions. Mechanistically, consolidating roles in one face reduces viewers’ extraneous processing demands (H1), and this efficiency spills over to more favorable account evaluations (H2) and, via higher perceived authenticity, to stronger purchase intentions (H3–H4). Mediation analyses consistently show a chain of influence—Casting → Cognitive Load → Brand Authenticity → Purchase Intention—with cognitive load as the primary driver and authenticity as a downstream conduit (H5a–H5b). These effects are not uniform: they intensify for individuals high in Need for Closure (Experiment 2; H6) and reverse by brand type such that one-actor casting benefits “entertaining/exciting” brands but can disadvantage “serious/competence-oriented” brands (Experiment 3; H7). Finally, Experiment 4 rules out an alternative explanation that attributes the one-actor advantage to perceived frugality or sympathy: a high-budget cue neither attenuates the effect nor renders sympathy or perceived cost constraint diagnostic in mediation, reinforcing a processing-based account.

Taken together, the results suggest that casting—often treated as a creative executional choice—has theoretically predictable consequences in feed-based, swipeable environments. The same narrative economy that makes single-performer ads easy to follow (lower extraneous load) also makes them feel more candid and less contrived (higher authenticity), thereby translating scarce attentional windows into persuasion. The pattern generalizes across delivery modes (video vs. text vignettes), settings (lab-like vs. field), and lead gender (male/female leads in 1a/1b), while remaining sensitive to audience motives (Need for Closure) and brand-schema expectations. Conceptually, the findings position short-form advertising not as “shorter TV,” but as a context-embedded persuasion episode in which capacity constraints and heuristic inferences interact with brand-fit considerations to shape outcomes.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.1.1. Reframing Casting in Feed-Based Persuasion Through Capacity Limits

Classic advertising wisdom holds that more characters enrich realism and credibility [

17,

18]. Our results qualify this view for short-form, feed-embedded contexts: when exposure windows are measured in seconds, every additional face competes for limited working memory resources, elevating extraneous load [

6,

7]. By anchoring multiple personas to a single encoded face, one-actor ads reduce individuation demands and preserve resources for message comprehension—an implication consistent with limited-capacity perspectives on mediated processing [

9]. We thus extend traditional casting guidance to an environment where processing efficiency rather than scene richness becomes pivotal.

5.1.2. Establishing a Chain Mechanism That Links Cognitive Load to Authenticity-Based Persuasion

The study integrates cognitive load research with authenticity scholarship by demonstrating a sequential pathway: reductions in extraneous load produce metacognitive ease (processing fluency), which audiences heuristically map onto “this seems genuine,” elevating brand authenticity and purchase intention [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Importantly, the authenticity step is downstream of cognitive load rather than an independent channel, clarifying why the BA-only indirect effect is unreliably significant whereas the CL → BA link is robust across studies. This mechanism specifies how micro-narrative design can manufacture authenticity inferences without invoking artisanal production cues, broadening authenticity theory beyond craftsmanship and provenance to include cognitive-experiential fit in fast media.

5.1.3. Embedding the Account in Dual-Process Persuasion Frameworks

By lowering cognitive burden, one-actor casting shapes both the ability component of elaboration and the heuristic inferences that follow when ability/motivation are constrained—core ideas in dual-process theories such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model and the Heuristic–Systematic Model [

27,

28,

45]. Our moderation by Need for Closure (Experiment 2) formalizes how a chronic desire for decisiveness amplifies the value of executional simplicity: high-NFC viewers benefit most from identity streamlining, showing greater load reductions and stronger downstream effects. The framework thereby connects a creative lever (casting) to psychologically grounded route selection in short-video persuasion.

5.1.4. Specifying Boundary Conditions via Brand–Schema Congruity

Experiment 3 demonstrates that brand personality moderates the casting effect: for “entertaining/exciting” brands, quick persona switching is congruent, reinforcing authenticity and evaluations; for “serious/competence-oriented” brands, the same device can appear flippant, muting authenticity and lowering persuasion. This brand-fit dependence complements person-level moderation and links casting to schema-congruity accounts in branding [

13,

17,

18], offering a principled basis for when less is more and when more is warranted.

5.1.5. Ruling out Frugality-Driven Alternatives to Isolate a Processing Account

An alternative view is that single-performer ads look “low-budget,” eliciting sympathy or thrift admiration. Experiment 4 manipulates budget salience and measures perceived cost constraint and sympathy in a chain (PC → Sympathy), finding that neither the direct nor sequential paths explain outcomes; the one-actor advantage persists even under explicit high-budget cues. This strengthens the theoretical claim that the observed benefits are not artifacts of cost inferences but flow through capacity management and authenticity-as-fluency.

Collectively, these contributions elevate casting from a purely esthetic choice to a micro-architecture of processing in short-video ecosystems (e.g., TikTok/Douyin, Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts). They also provide a transferable template for theorizing other creative levers—editing density, captioning, or pacing—through their impacts on cognitive economy and heuristic signaling in fragmented media.

5.2. Practical Contributions

Short-form, feed-embedded environments reward clarity on the first pass. Our evidence shows that a single performer enacting multiple roles is often the most efficient way to deliver that clarity. Viewers identify one face while tracking several personas, which reduces processing friction and helps the narrative “click” within seconds. In practical terms, creative teams planning sub-60 s placements on TikTok, Douyin, Instagram Reels, or YouTube Shorts can treat a one-actor/multi-role execution as a strong baseline for high-attention moments, especially when the objective is rapid comprehension and immediate persuasion.

Creative fit with brand identity remains essential. For brands that prize excitement, playfulness, or youthful energy, one-actor role-switching naturally signals spontaneity and creative confidence. The same device can feel off-tone for competence-centric categories (e.g., finance, healthcare), where multiple presenters or domain experts better cue professionalism and trust. Practitioners should therefore align casting with brand-personality frameworks rather than defaulting to a single recipe [

17,

18]. When the brand is “fun,” a versatile performer can heighten perceived authenticity by making the message feel personal and handcrafted. When the brand is “serious,” a multi-actor arrangement can legitimize expertise without overloading viewers.

Audience segmentation tactics can further unlock value. People differ in their tolerance for ambiguity and preference for fast closure. Marketers can anticipate stronger gains from one-actor formats among consumers who favor decisiveness and unambiguous messaging. That profile can be approximated with platform analytics (e.g., low dwell on complex ads, higher completion when narratives are linear) and then targeted or A/B tested. Creative variants can be tuned to the same logic: one-actor spots may adopt straight-line “set-up → payoff” storytelling, whereas multi-actor variants can be reserved for segments that enjoy layered narratives without experiencing overload.

Talent selection and briefing should conserve attention for meaning rather than identity parsing. Casting a performer with demonstrated range—vocal, facial, and physical—helps role transitions remain legible at a glance. Wardrobe and prop changes should be minimal but diagnostic; one clear cue per role is often sufficient. On-screen text can label roles sparingly to prevent clutter. When appropriate, a concise end card or caption can make the creative choice transparent (e.g., “All roles portrayed by [Name] to illustrate [Benefit]”). Such transparency reinforces intentionality without inviting budget attributions and can enhance perceived authenticity by foregrounding craft rather than thrift [

14,

31].

Measurement and optimization should reflect the mechanisms identified in our studies. Pre-launch tests can probe perceived mental effort and message clarity alongside standard brand metrics. In-platform signals such as early-scroll rates, view-through, and short rewinds provide pragmatic proxies for processing ease in fast feeds. For campaigns that pair brand-building with response objectives, decision rules can privilege one-actor variants when attention curves are steep (e.g., mobile peak hours or crowded feeds) and switch to multi-actor variants when credibility cues are paramount (e.g., regulatory updates or service explanations). Influencer collaborations deserve the same discipline. Creators known for sketch or impersonation styles are natural partners for one-actor executions, provided the tone stays on-brand. Creators with professional gravitas are better suited to multi-voice formats that spotlight expertise.

Production signaling should be managed deliberately. Our data indicate that explicitly communicating “high budget” does not weaken the one-actor advantage, suggesting that budget inferences are not the driver of effectiveness. Lightly signaling the creative rationale—through behind-the-scenes clips, pinned comments, or press notes—can preempt misinterpretations and amplify the sense of design intentionality. The goal is not to justify cost but to curate how audiences read the craft choices that make short-video storytelling legible, memorable, and persuasive.

Taken together, these recommendations emphasize fit and focus. Short-video advertising is not a compressed version of television; it is a different persuasion episode with different constraints. Teams that match casting to brand personality, tune variants to audience processing styles, and measure success with attention-aware diagnostics can harness the one-actor/multi-role strategy to cut through clutter while preserving credibility where it matters [

14,

17,

18,

31].

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The present program of studies was designed to isolate casting format as the focal executional lever in short-form video advertising, and that focus necessarily imposes scope conditions. One limitation concerns brand familiarity and equity. To avoid carryover from prior attitudes, we relied on fictitious or unfamiliar brands in several studies. In applied settings, preexisting equity, spokesperson fit, and celebrity reputations may either amplify or dampen the effects reported here by shifting baseline credibility or altering authenticity attributions. Follow-up work could embed the same casting manipulations within well-known brands or ongoing creator–brand relationships to estimate how equity and endorsement histories shape the net persuasive return of a single-actor approach.

A second limitation involves message genre and goal diversity. Our scenarios emphasized lighthearted, informational-to-persuasive micro-narratives, which are common on feed-based platforms but not exhaustive. Short videos can also be testimonial, instructive, or somber, and those genres may recruit different cues to credibility than the ones highlighted here. It remains an open question whether a one-actor execution supports delicate topics (e.g., safety, finance, health) without diluting perceived competence, or whether an ensemble cast conveys gravitas more effectively. Mapping the boundary conditions across genres—documentary-style, testimonial, episodic storytelling, or high-action formats—would help translate the present mechanisms to a fuller portfolio of creative objectives.

Beyond cost-frugality and sympathy, real-world responses can also be shaped by perceived entertainment value and performer charisma. Our designs mitigate these influences by using text-only storyboards with constant scripts (Studies 2–4) and matched pacing and claims in video stimuli (Studies 1a/1b), which isolate casting structure from performance style. Nevertheless, future work should explicitly measure and, where feasible, manipulate entertainment value and performer charisma—or include them as covariates or fixed effects—to further bound their impact in feed-embedded settings.

A third limitation relates to additional person- and context-level moderators beyond those tested. We theorized and found moderation by Need for Closure and by brand type, but heterogeneity may also arise from platform familiarity, advertising involvement, sensation seeking, device constraints, or viewing context (e.g., in transit versus at home). These factors plausibly alter tolerance for cognitive burden and the threshold at which “many roles” create confusion, and they could be examined through targeted sampling or platform analytics. Although our samples spanned a broad adult age range, short-video consumption skews young on many platforms; future research can probe whether the casting effects replicate or shift in magnitude in Gen-Z–heavy cohorts and in older segments that consume short video regularly.

A further consideration is ecological validity in a highly audiovisual medium. Text-only stimuli in Studies 2–4 were a deliberate choice to isolate identity-cue density from facial appearance, voice quality, and editing, but the trade-off is reduced sensory fidelity relative to real feeds. Converging designs that combine controlled casting manipulations with richer production—alongside objective traces such as view-through rates, dwell time, or scroll latency—would strengthen external validity without reintroducing confounds. Physiological and process-tracing measures (e.g., eye tracking, secondary-task reaction time) could also triangulate the cognitive-load account while preserving the feed-embedded experience.

Finally, the present studies used brief, validated multi-item reports for cognitive load, authenticity, account impression, and purchase intention within single sessions. This common structure facilitates comparability across experiments but does not exhaust the space of measurement strategies. Future work might supplement self-reports with behavioral choice tasks, follow-ups on delayed recall, or platform-native outcomes (e.g., click-through or follow intent realized in subsequent behaviors). Together, these extensions would clarify where the one-actor advantage holds most strongly and how it scales with brand equity, creative genre, audience composition, and real-world viewing conditions, while preserving the theoretical core that casting-induced efficiency in identity processing cascades into authenticity and persuasion in short-form feeds.