Intergenerational Differences in Impulse Purchasing in Live E-Commerce: A Multi-Dimensional Mechanism of the ASEAN Cross-Border Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Gaps and Research Objectives

1.2.1. Research Gaps

1.2.2. Research Objectives

2. Literature Review

2.1. Economic Dimension: Intergenerational Mapping of Market Size and Consumption Capacity

2.2. Policy Dimensions: Intergenerational Regulation of Consumption Decisions by Institutional Environment

2.3. Cultural Dimensions: Value Divide and Intergenerational Behavioral Mechanisms

2.4. Variable Selection and Hypothesis Establishment

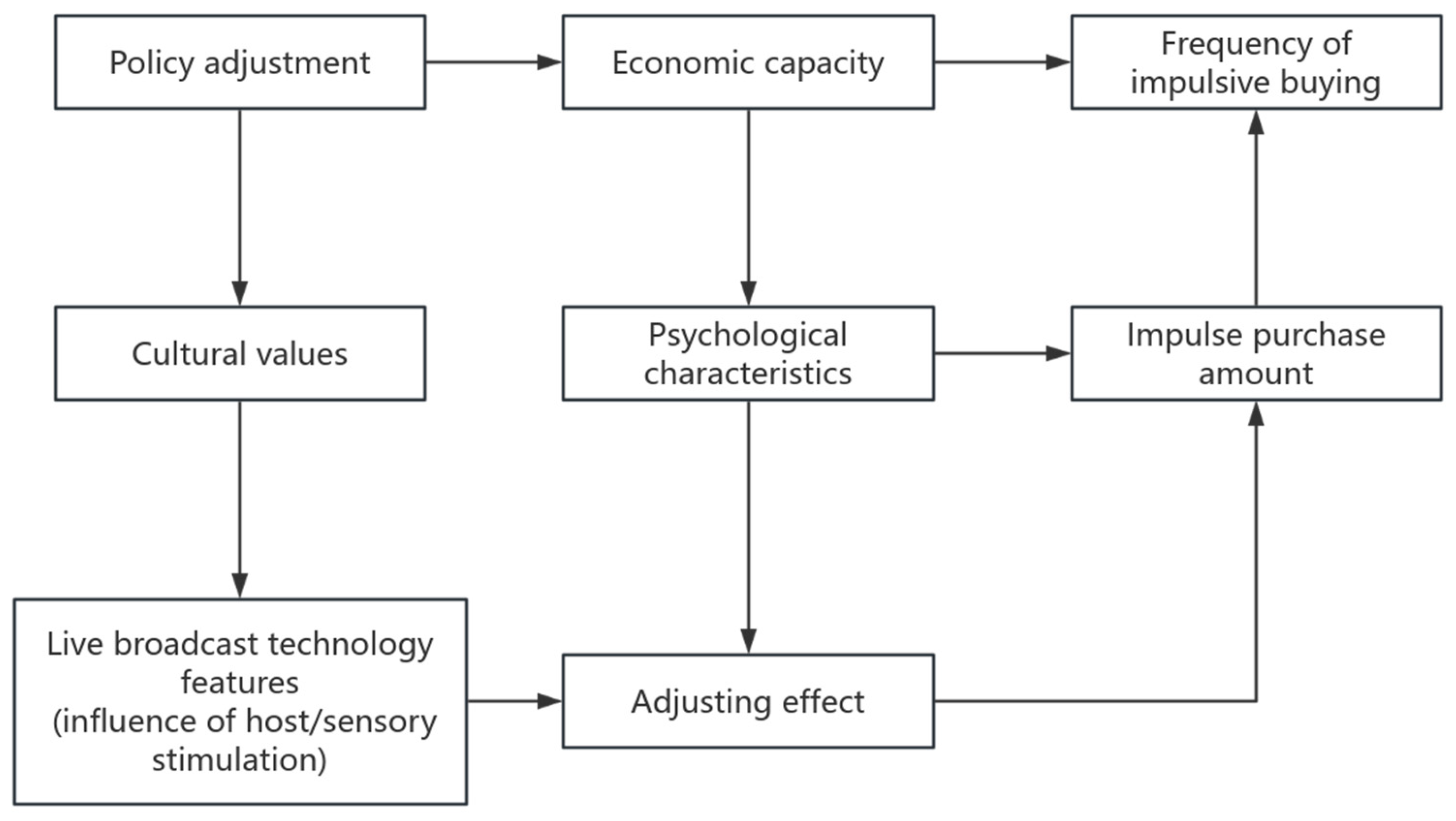

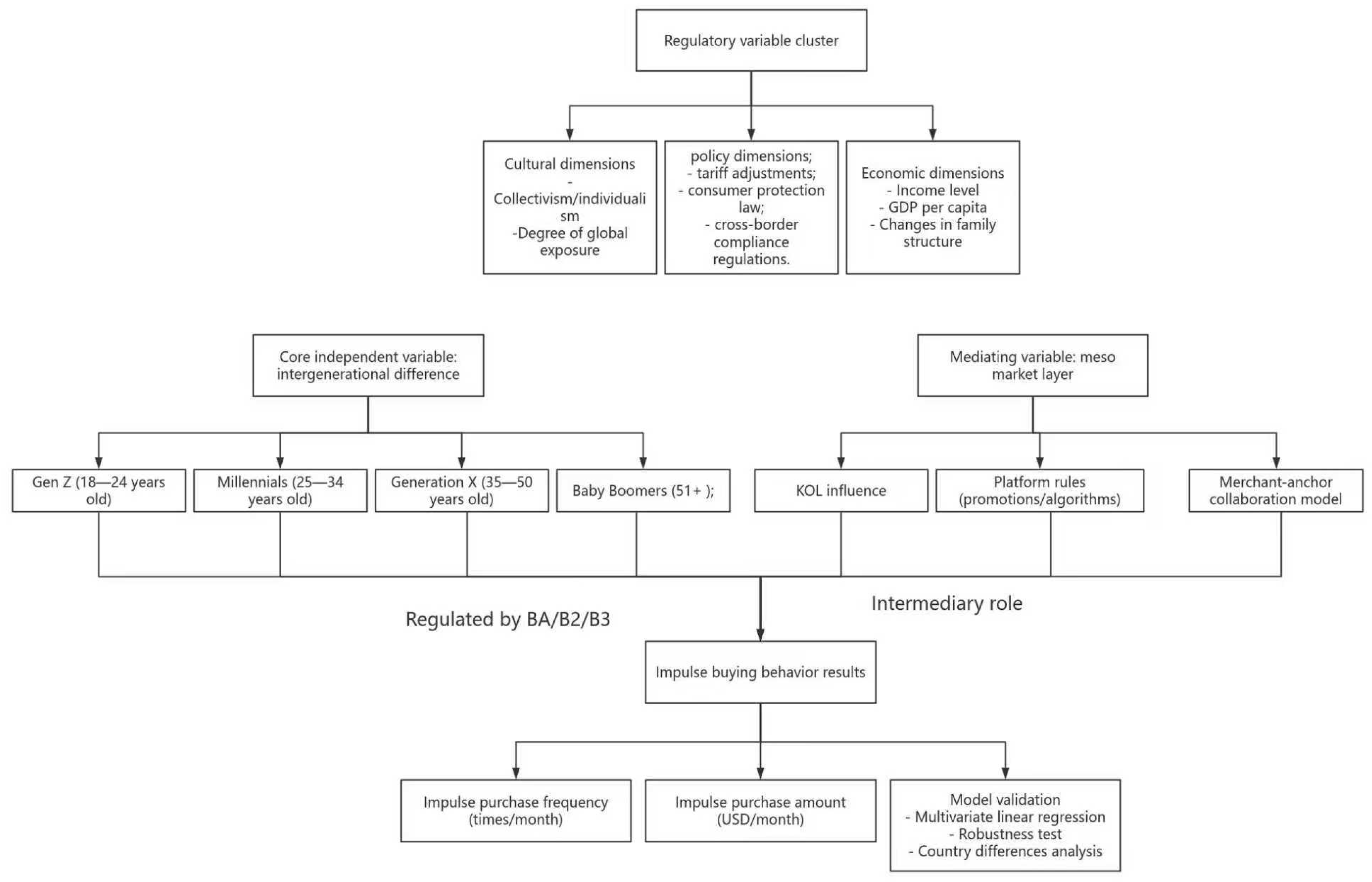

2.4.1. Three-Level Framework Refinement

2.4.2. Three-Tier Framework Variables Definition and ASEAN Case Table

2.5. Research Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Sources of Data

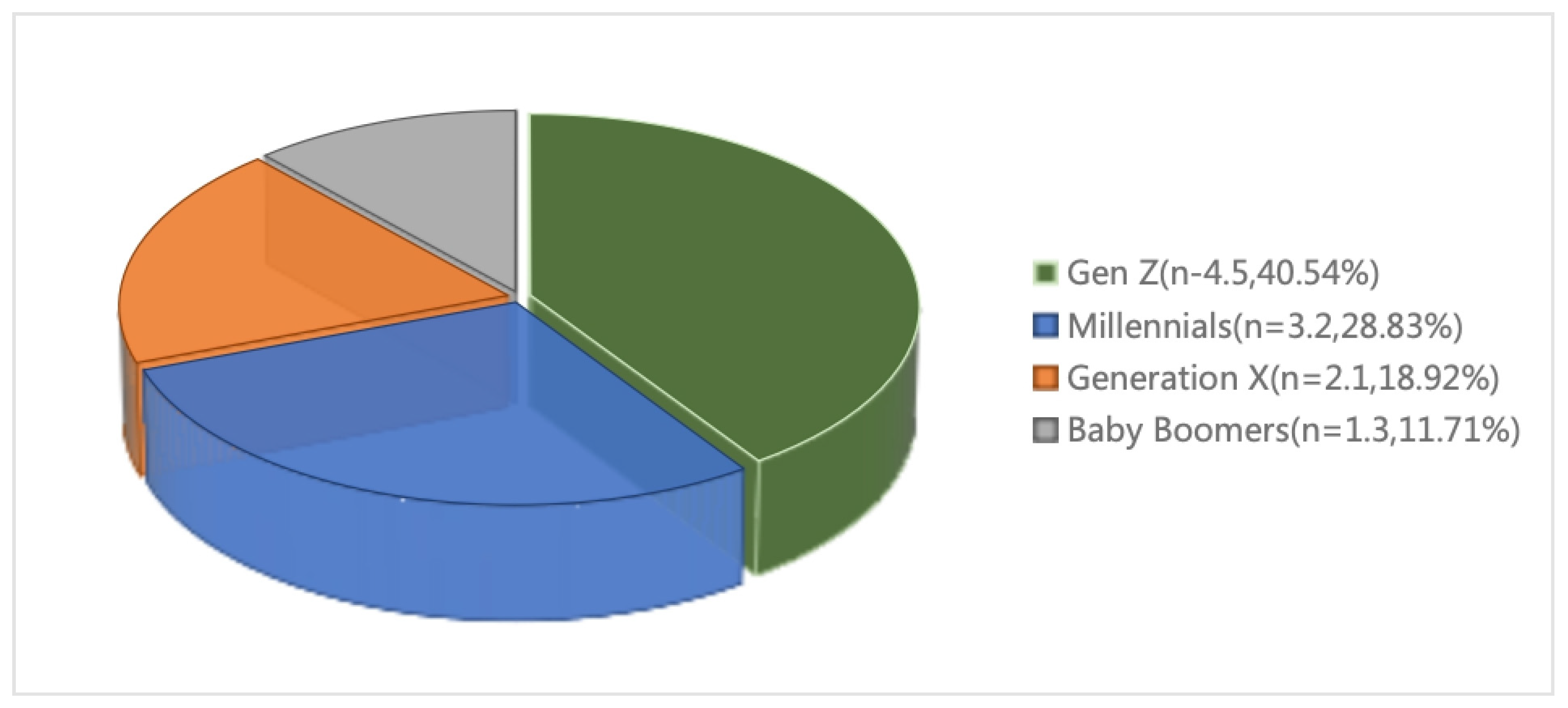

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.2.1. Rationale for the Sampling Method

3.2.2. Sample Reliability Test

3.3. Variable Setting

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Key Variable Measurement Logic

3.4. Model Construction and Method Effectiveness Demonstration

3.4.1. Model Setting

3.4.2. Rationale for Method Selection

- (1)

- The density of internet infrastructure is highly correlated with the level of income (correlation coefficient = 0.68, p < 0.001), because the better infrastructure is more developed in the digital economy, with more employment opportunities and higher income levels.

- (2)

- Exogeneity: The number of fiber ports is a national-level public infrastructure index that is not directly related to the individual’s impulsive buying behavior (e.g., the density in a country would not change due to whether the individual impulse shops or not), satisfying the exogeneity assumption of the instrumental variable. The 2SLS regression results show that the coefficient of the income variable is 0.0003 (p < 0.05), which is consistent with the direction of the benchmark OLS regression (coefficient = 0.0002, p < 0.05), indicating that the endogeneity does not significantly distort the estimation results.

3.4.3. Robustness Check Strategy

3.5. Ethical Compliance

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Regression Results Analysis

4.2.1. Impulse Purchase Frequency Model

4.2.2. Impulsive Purchase Amount Model

4.3. Mechanism Analysis of Country Differences

4.4. Cross-Dimensional Comparative Analysis

4.4.1. Analysis of National Differences

4.4.2. Industry Difference Analysis

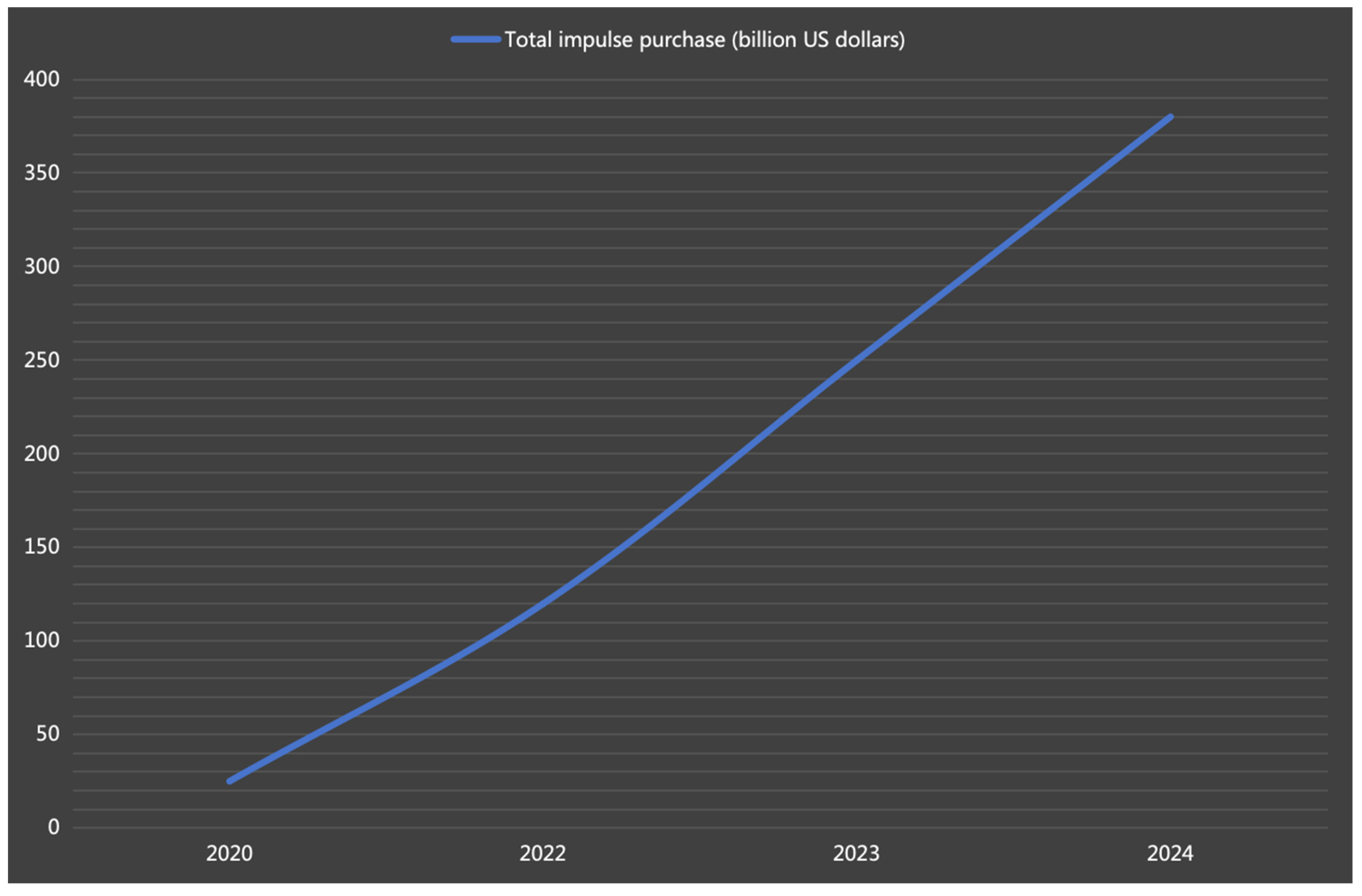

4.4.3. Cross-Year Trend Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution: Interdisciplinary Integration and Scenario-Based Expansion of Classic Theories

5.2. Exploration of Possible Alternative Theories and Mechanisms

5.3. Limitations

5.3.1. Limitations of Sample Selection

5.3.2. Limitations of Research Methodology

5.3.3. Limitations of Variable Measurement

5.3.4. Limitations of the Scope of This Study

5.4. Discussion on the Fitting of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension Framework

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Findings

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FMCG | Fast-moving consumer goods |

| KOL | Key Opinion Leader |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| TCPC | Total Customer-Perceived Cost |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| GLS | Generalized Least Squares |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| RCEP | Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| ERP | Event-Related Potential |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| S-O-R | Stimulus–Organism–Response Model |

| IV | Instrumental variable |

| VIFs | Variance inflation factors |

References

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, K. How Live Streaming Features Impact Consumers’ Purchase Intention in the Context of Cross-Border E-Commerce? A Research Based on SOR Theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 767876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yu, R.W.L.; Liu, C.; Sörensen, S.; Lu, N. Digital Literacy, Intergenerational Relationships, and Future Care Preparation in Aging Chinese Adults in Hong Kong: Does the Gender of Adult Children Make a Difference? Health Soc. Care Community 2025, 2025, 6198111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghanibehambari, H. Intergenerational health effects of Medicaid. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2022, 45, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wei, S.; Shen, J. The Effect of Herd Behavior on Consumer Intention in Live Streaming E-Commerce: The Moderating Role of Interaction. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 1674–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wan, M.; Qiu, S. Choice of product quality in supply chain of live-streaming e-commerce under different power structures. Aust. J. Manag. 2023, 50, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y.; Ding, L. Live streaming e-commerce supply chain decisions considering dominant streamer under agency selling and reselling formats: Live streaming e-commerce supply chain decisions. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 25, 1173–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, T. The Role of Live-Streaming E-Commerce on Consumers’ Purchasing Intention regarding Green Agricultural Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Huang, L. How the time-scarcity feature of live-streaming e-commerce affects impulsive buying. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fu, L.; Ma, J.; Chen, C. Social-oriented versus task-oriented streamer interaction styles on live streaming e-commerce: Empirical research in China. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.H.; Li, Q. What Drives Consumer Shopping Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce? J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Lü, K.; Fang, W. Machines vs. humans: The evolving role of artificial intelligence in livestreaming e-commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 188, 115077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Ali, M.H.; Omar, N.A.; Siddik, A.B. Impulsive hotel consumption intention in live streaming E-commerce settings: Moderating role of impulsive consumption tendency using two-stage SEM. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 115, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Chen, X.; Wei, S. What Motivates Consumers’ Purchase Intentions in E-Commerce Live Streaming: A Socio-Technical Perspective. International Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 1585–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, K.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Dong, L.; Jiang, W. Whether Live Streaming Has a Better Performance? An Examination of Product Presentation Modes on Cross-Border E-Commerce Platform. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Candelas, C.; Polanco-Roman, L.; Duarte, C.S. Intergenerational Effects of Racism: Can Psychiatry and Psychology Make a Difference for Future Generations? JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloome, D.; Pace, G.T. Family Tree Branches and Southern Roots: Contemporary Racial Differences in Marriage in Intergenerational and Contextual Perspective. Am. J. Sociol. 2024, 129, 1084–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y. Research on the Spatial and Temporal Patterns and Formation Mechanisms of Intergenerational Health Mobility in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 173, 709–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, J. Internet Use and Mental Health among Older Adults in China: Beneficial for Those Who Lack of Intergenerational Emotional Support or Suffering from Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2024, 26, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Gazit, T.; Nisim, S. Intergenerational family online community and older adults’ overall well-being. Online Inf. Rev. 2023, 47, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M. Intergenerational transmission of fertility outcomes in Spain. Manch. Sch. 2021, 89, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.L.; Maslen, S.; Watkins, R.; Conigrave, K.; Freeman, J.; O’Donnell, M.; Mutch, R.C.; Bower, C. ‘That thing in his head’: Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australian caregiver responses to neurodevelopmental disability diagnoses. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, R.; Zhao, Z. Free education and the intergenerational transmission of cognitive skills in rural China. J. Popul. Econ. 2025, 38, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capistrano, D.; Creighton, M.J.; Işıklı, E. I Guess We are from Very Different Backgrounds: Attitudes Towards Social Justice and Intergenerational Educational Mobility in European Societies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 171, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, N.; Vieira, E.R.; Awuviry-Newton, K.; Kapilashrami, A.; Khan, H.T. Intergenerational differences in walking for transportation between older men and women in six countries. J. Transp. Health 2023, 31, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holstein, E.; Walker, C. Reframing environmental responsibility at the intersections of cultural and generational difference: Learning from migrant families in Manchester and Melbourne. Geoforum 2023, 146, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, H.; Dave, D.M.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Reichman, N.E. Effects of welfare reform on household food insecurity across generations. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2022, 45, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, H.; Nakamura, T. Population growth and intergenerational mobility. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 27, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.N.; Burke, P.J. Is ASEAN ready to move to multilateral cross-border electricity trade? Asia Pac. Viewp. 2023, 64, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D. RCEP rules on cross-border data flows: Asian characteristics and implications for developing countries. Asia Pac. Law Rev. 2025, 33, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southeast Asia E-Commerce Market Insights and Forecasts 2024–2029. Research and Markets, 2024. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Gillet, P.; Le, P.; Nguyen, D.K. Banking integration and market competition: Evidence from the ASEAN-6 countries. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 3904–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google; Temasek; Bain & Company. e-Conomy SEA 2024: Powering Forward; Bain & Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, C.; Kasman, A.; Hamid, F.S. Impact of foreign ownership on market power: Do regional banks behave differently in ASEAN countries? Econ. Model. 2021, 105, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rakhmah, T.F.; Wada, J. Market Design for Multilateral Trade of Electricity in ASEAN: A Survey of the Key Components and Feasibility. Asian Econ. Pap. 2020, 19, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, A.S.; Gayatri, G. The Role of Live Streaming in Building Consumer Trust, Engagement, and Purchase Intention in Indonesian Social Commerce Thrift Clothes Sellers. ASEAN Mark. J. 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J. Tourism e-commerce live streaming: Identifying and testing a value-based marketing framework from the live streamer perspective. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, J. The Influences of Live Streaming Affordance in Cross-Border E-Commerce Platforms: An Information Transparency Perspective. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, P.; Yu, W. Gender differences in rural education in China. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2021, 27, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hsu, F.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y. Personal Brand Equity and Telepresence’s Role in Tourism Electronic Commerce Live Streaming. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, H.; Jia, Q. A meta-analytic review of live streaming commerce research through the lens of means-end-chain. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 195, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lee, Y.-C. The effect of live streaming commerce quality on customers’ purchase intention: Extending the elaboration likelihood model with herd behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Esperanqa, J.P.; Wu, Q. Effects of Live Streaming Proneness, Engagement and Intelligent Recommendation on Users’ Purchase Intention in Short Video Community: Take TikTok (DouYin) Online Courses as an Example. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 3071–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, J.; Lyu, D. An ERP study on the role of instant purchasing group quantity in e-commerce live streaming: A social impact perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 30963–30973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. How to Use Live Streaming to Improve Consumer Purchase Intentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Chenn, A.; Chong, S.M.; Cho, E. Is livestream shopping conceptually New? a comparative literature review of livestream shopping and TV home shopping research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174, 114504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Wan, C. The Impact of Mukbang Live Streaming Commerce on Consumers’ Overconsumption Behavior. J. Interact. Mark. 2023, 58, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W. The Influence of the Characteristics of Internet Celebrities on Fans’ Purchase Int in Live Broadcasting Platforms. China Circ. Econ. 2020, 34, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Lu, M. The Empirical Research on Impulse Buying Intention of Live Marketing in Mobile Internet Era. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Chen, J.; Nguyen, T.M.T. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Intention in Vietnam-China Cross-border E-commerce: An Empirical Study in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Econ. Public Financ. 2022, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.J.; Meng, L.; Chen, S.Y.; Duan, C. The Impact of Network Celebrities’ Information Source Characteristics on Purchase Intention. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.S.; Tang, S.H.; Xiao, J. Research on Consumers’ Purchase Intention on E-commerce Livestreaming Platforms--Based on the Perspective of Social Presence. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2021, 43, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.S.; Zhang, Q.P.; Zhao, C.G. The Influence of Webcast Characteristics on Consumers’ Purchase Intention under E-commerce Live Broadcasting Mode—The Mediating Role of Consumer Perception. China Bus. Mark. 2021, 35, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Understanding the Relationship between IT Affordance and Consumers’ Purchase Intention in E-Commerce Live Streaming: The Moderating Effect of Gender. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 6303–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y. The Real Situation and Path Reconstruction of China-ASEAN Cross-border E-commerce Development. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 29, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yanjiao, T.; Xiaomin, N. Research on the Influencing Factors and Mechanism of Consumer Purchase Behavior in E-commerce Live Broad—Based on the Perspective of Enterprise Control. J. Mod. Bus. 2024, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. The driving force, realistic problems and path selection of enterprise live e-commerce in the era of digital economy. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Indonesia | Vietnam | Cambodia | Malaysia | Thailand | Singapore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Issue regulations to promote compliance and sustainable development of e-commerce enterprises | Start to lay out the standardization of e-commerce transactions | - | - | - | - |

| 2020 | - | - | Initiate e-commerce strategy, involving payment, logistics, legal supervision, etc. | - | - | - |

| 2021 | - | - | - | Launch the National E-commerce Strategy Roadmap 2.0 | - | - |

| 2022 | - | - | - | - | Adjust the Advertising Law, affecting the placement of e-commerce ads. | - |

| 2023 | - | Enacted the new Consumer Rights Protection Law and Electronic Transactions Law | - | - | Continue to improve the relevant details of the Advertising Law | - |

| 2024 | - | - | - | - | - | Improve Consumer Protection Law |

| Analytical Hierarchy | Core Definitions | Included Variables | ASEAN Scenario Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macro-institutional layer | National/regional-level systemic rules and economic environment, building the basic order for cross-border transactions. | Cross-border policies (tariff adjustments and consumer protection laws), economic gradients (GDP per capita and income levels), and cultural values (collectivism/individual overall orientations). | 1. The revision of the 2023 Vietnam Electronic Transaction Law regulates the after-sales process of live e-commerce. 2. Singapore’s per capita GDP exceeds USD 60,000, supporting high customer price point impulse consumption. 3. Cambodia’s Hofstede collectivism index is 0, and the overall consumption decision is more dependent on group opinions. |

| Intermediate market layer | A market intermediary system that connects supply and demand, conveys value, and matches resources. | Influencer effect (KOL/KOC influence), platform rules (live-broadcast algorithm and promotion mechanism), and interaction of market entities (merchant–anchor–consumer collaboration model). | 1. Thai beauty influencers drive a 35% increase in the conversion rate of Millennials’ impulsive skincare purchases through compliant recommendations. 2. Shopee Live launches the “Flash Sale” mechanism in Malaysia, stimulating immediate orders across generations. 3. Indonesian merchants collaborate with local hosts to lower consumer trust thresholds through dialect live streaming. |

| Micro-behavioral layer | The psychological and behavioral characteristics of individual consumers directly determine the decision to make an impulse purchase. | Individual media usage habits (social media time), brand loyalty, and impulsive buying psychology (tendency for immediate gratification). | 1. Gen Z in ASEAN spends an average of 4.5 h on social media daily, with frequent exposure to live content triggering impulse buying. 2. Baby Boomers have a brand loyalty of 0.9, making impulse purchases only due to trust in traditional brands. 3. Millennials have a significant tendency towards ‘instant gratification’, ordering limited-edition electronic products immediately when they see them on live broadcasts. |

| State Areas | DP Share (2024) | E-commerce Penetration Rate (2024) | Weighted Score | Sample Proportion | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 40.2% | 70.5% | 0.523 | 30% | 450 |

| Malaysia | 15.8% | 65.3% | 0.352 | 20% | 300 |

| Thailand | 18.5% | 58.7% | 0.346 | 15% | 225 |

| Philippines | 12.3% | 52.1% | 0.278 | 15% | 225 |

| Vietnam | 9.7% | 61.2% | 0.294 | 10% | 150 |

| Other countries (Singapore, Cambodia, etc.) | 3.5% | 45.0% | 0.191 | 10% | 150 |

| Total | 100% | - | - | 100% | 1500 |

| Generation | Age Range | Sample Size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation Z | 18–24 | 150 | 30% |

| Millennials | 25–34 | 130 | 26% |

| Generation X | 35–50 | 120 | 24% |

| Baby Boomers | 51+ | 100 | 20% |

| Metric | Example Questions | Type of Question (Scale/Scoring Method) | Score Corresponding to the Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social media use (h/day) | “How long on average do you spend a day using social media (Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc.)?” | A single-choice scale (1. <1 h; 2. 1–2 h; 3. 2–3 h; 4. 3–4 h; 5. > 4 h), which is subsequently converted into a continuous numerical variable | 1. Retention rate scale: 1 point = <20%, 2 points = 20–40%, 3 points = 40–60%, 4 points = 60–80%, 5 points = >80% 2. Recommendation likelihood scale: 1 point = extremely unlikely, 2 points = very unlikely, 3 points = not very likely, 4 points = somewhat unlikely, 5 points = neither likely nor unlikely, 6 points = somewhat likely, 7 points = not very likely (here modified to “somewhat likely”), 8 points = very likely, 9 points = extremely likely, 10 points = absolutely would recommend; NPS calculation rule: percentage of promoters (9–10 points)—percentage of detractors (1–6 points) 3. Brand loyalty final score = (Retention rate scale score/5) × 0.5 NPS × 0.5 (score range: −0.5~1) |

| Live use (weekly frequency) | “How many times on average do you watch live e-commerce (e.g., Shopee Live and Lazada Live) per week?” | Single choice scale (1. 0 times; 2. 1–2 times; 3. 3–4 times; 4. ≥5 times), directly as an ordered categorical variable | 1 point = 0 times/week; 2 points = 1–2 times/week; 3 points = 3–4 times/week; 4 points = ≥5 times/week |

| Brand loyalty | 1. “What percentage of purchases made in the past six months were repeat purchases of the same brand?” 2. “How likely are you to recommend a common brand to your friends and family?” | 1. Single choice scale (1. <20 percent; 2. 20–40 percent; 3. 40–60 percent; 4. 60–80 percent; 5. > 80 percent) 2. 10-point scale (1 = highly unlikely, 10 = highly likely), calculated NPS and weighted equally with repurchase rate (each 0.5) | 1. Retention rate scale: 1 point = <20%, 2 points = 20–40%, 3 points = 40–60%, 4 points = 60–80%, 5 points = >80% 2. Recommendation likelihood scale: 1 point = extremely unlikely, 2 points = very unlikely, 3 points = not very likely, 4 points = somewhat unlikely, 5 points = neither likely nor unlikely, 6 points = somewhat likely, 7 points = not very likely (here modified to “somewhat likely”), 8 points = very likely, 9 points = extremely likely, 10 points = absolutely would recommend; NPS calculation rule: percentage of promoters (9–10 points)—percentage of detractors (1–6 points) 3. Brand loyalty final score = (Retention rate scale score/5) × 0.5 NPS × 0.5 (score range: −0.5~1) |

| Promotional appeal | “How interested are you in promotional activities in live-streaming e-commerce (such as limited-time discounts, full reduction, and freebies)?” | 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all interested, 7 = very interested) | 1. Retention rate scale: 1 point = <20%, 2 points = 20–40%, 3 points = 40–60%, 4 points = 60–80%, 5 points = >80% 2. Recommendation likelihood scale: 1 point = extremely unlikely, 2 points = very unlikely, 3 points = not very likely, 4 points = somewhat unlikely, 5 points = neither likely nor unlikely, 6 points = somewhat likely, 7 points = not very likely (here modified to “somewhat likely”), 8 points = very likely, 9 points = extremely likely, 10 points = absolutely would recommend; NPS calculation rule: percentage of promoters (9–10 points)—percentage of detractors (1–6 points) 3. Brand loyalty final score = (Retention rate scale score/5) × 0.5 NPS × 0.5 (score range: −0.5~1) |

| Anchor’s influence | “How much influence do the anchors’ product recommendations have on your decision to buy a product during the broadcast?” | 7-point Likert scale (1 = no effect, 7 = very much) | 1 point = no effect; 2 points = minimal effect; 3 points = slight effect; 4 points = moderate effect; 5 points = considerable effect; 6 points = high effect; 7 points = extreme effect |

| Product display effect | “How attractive do you think the presentation of products in the live broadcast (e.g., visual clarity, completeness of selling point explanation, and scenario-based demonstration) will be?” | 7-point Likert scale (1 = extremely low attraction, 7 = extremely high attraction) | 1 point = Extremely low attractiveness; 2 points = Low attractiveness; 3 points = Slightly low attractiveness; 4 points = Average; 5 points = Slightly high attractiveness; 6 points = High attractiveness; 7 points = Extremely high attractiveness. |

| Collectivism/individualism | “Do you prioritize the opinions of friends and family or the group over your personal preferences before purchasing important items?” | 7-point Likert scale (1 = never, 7 = always), with 6 items | Scoring of individual items: 1 point = not at all; 2 points = very little; 3 points = not very well; 4 points = average; 5 points = somewhat well; 6 points = very well; 7 points = definitely would; Total score = sum of scores on the 6 items/6 (Scoring range: 1~7, higher scores indicate a stronger tendency toward collectivism, and lower scores indicate a stronger tendency toward individualism). |

| Power distance | “Do you trust products recommended by authoritative experts or official institutions more than the evaluations of ordinary consumers?” | 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely distrusting, 7 = very trusting), with 4 items | Item Scoring: 1 point = Completely distrusting/disagree; 2 points = Very distrusting/disagree; 3 points = Somewhat distrusting/somewhat disagree; 4 points = Neutral; 5 points = Somewhat trust/somewhat agree; 6 points = Very trust/very agree; 7 points = Complete trust/agree; Total Score = sum of 4 item scores/4 (Scoring range: 1~7, higher scores represent a stronger power distance tendency) |

| Variable | Z for Generations | Millennials | X for Generations | Baby Boomers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulse purchase frequency (times/month) | 4.5 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.3 |

| Impulse purchase amount (USD/month) | 80 | 120 | 150 | 200 |

| Age (years) | 21 | 30 | 42 | 60 |

| Sex (percentage male) | 40% | 42% | 48% | 52% |

| Income (USD/month) | 600 | 1200 | 2500 | 3000 |

| Time spent on social media (hours/day) | 4.5 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Frequency of live-streaming e-commerce (times/week) | 5.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| Brand loyalty (frequency of repeat purchases) | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Attractiveness of live-streaming promotion (1–5 points) | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| Influencer power (1–5) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Product display effect (1–5 points) | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Intergeneration | Impulse Purchase Frequency (Times/Month) | Impulse Purchase Amount (USD/Month) | Core Drivers | Typical Commodity Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation Z | 4.5 | 80 | Social media immersion, KOL influence, and personalized design | Trendy clothes, creative accessories, and low-price FMCG |

| Millennials | 3.2 | 120 | Brand tone, product quality, and user reputation | Electronics, fashion, and luxury goods |

| Generation X | 2.1 | 150 | Cost performance, functional utility, and life cycle cost considerations | Household and durable consumer goods |

| Baby Boomers | 1.3 | 200 | Brand loyalty, quality reliability, and trust in traditional media | Health care products, traditional clothing, and high-end durable goods |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | -Value | -Value | 95% Confidence Interval | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational variables | Gen_Millennia | −0.8 | 0.35 | −2.29 | 0.023 | [−1.49, −0.11] [−1.49, −0.11] | 1.25 |

| Gen_X | −1.5 | 0.42 | −3.57 | 0.000 | [−2.32, −0.68] | 1.30 | |

| Gen_Boomer | −2.3 | 0.51 | −4.51 | 0.000 | [−3.30, −1.30] | 1.28 | |

| Controlled variables | Age | −0.12 | 0.03 | −4.00 | 0.000 | [−0.18, −0.06] | 1.15 |

| Sex (male = 1) | −0.35 | 0.20 | −1.75 | 0.080 | [−0.74, 0.04] | 1.05 | |

| Income | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 2.00 | 0.045 | [0.0000, 0.0004] | 1.35 | |

| Educational level (college) | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.549 | [−0.34, 0.64] | 1.40 | |

| Educational level (undergraduate) | 0.28 | 0.27 | 1.04 | 0.300 | [−0.25, 0.81] | 1.50 | |

| Education (master’s degree or above) | 0.32 | 0.31 | 1.03 | 0.304 | [−0.29, 0.93] | 1.45 | |

| Consumer behavior variables | Time spent using social media | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.13 | 0.002 | [0.09, 0.41] | 1.60 |

| Frequency of live-streaming e-commerce | 0.40 | 0.06 | 6.67 | 0.000 | [0.28, 0.52] | 1.55 | |

| Brand loyalty | −0.50 | 0.10 | −5.00 | 0.000 | [−0.70, −0.30] | 1.30 | |

| Marketing factor variables | Promotional appeal | 0.30 | 0.07 | 4.29 | 0.000 | [0.16, 0.44] | 1.40 |

| The influence of the anchor | 0.28 | 0.06 | 4.67 | 0.000 | [0.16, 0.40] | 1.35 | |

| Product display effect | 0.22 | 0.05 | 4.40 | 0.000 | [0.12, 0.32] | 1.25 | |

| Constant term | 5.80 | 0.60 | 9.67 | 0.000 | [4.62, 6.98] | 1.00 | |

| Model fitting | R squared | 0.68 | |||||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.65 | ||||||

| -Value | 28.50 | 0.000 | |||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | -Value | -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational variables | Gen_Millennia | 25 | 12 | 2.08 | 0.038 |

| Gen_X | 40 | 15 | 2.67 | 0.008 | |

| Gen_Boomer | 60 | 18 | 3.33 | 0.001 | |

| Controlled variables | Age | 2.5 | 0.8 | 3.13 | 0.002 |

| Sex (male = 1) | 15 | 8 | 1.88 | 0.065 | |

| Income | 0.15 | 0.05 | 3.00 | 0.003 | |

| Educational level (college) | 10 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.317 | |

| Educational level (undergraduate) | 20 | 12 | 1.67 | 0.095 | |

| Education (master’s degree or above) | 30 | 15 | 2.00 | 0.045 | |

| Consumer behavior variables | Time spent using social media | −5 | 3 | −1.67 | 0.095 |

| Frequency of live-streaming e-commerce | 10 | 4 | 2.50 | 0.012 | |

| Brand loyalty | 30 | 8 | 3.75 | 0.000 | |

| Marketing factor variables | Promotional appeal | 15 | 4 | 3.75 | 0.000 |

| The influence of the anchor | 12 | 3 | 4.00 | 0.000 | |

| Product display effect | 10 | 3 | 3.33 | 0.001 | |

| Constant term | 50 | 15 | 3.33 | 0.001 | |

| Model fitting | R squared | 0.72 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.69 | ||||

| -Value | 32.00 | 0.000 | |||

| Country | Impulse Purchase Frequency (Times/Month) | Average Order Value (USD) | Anchor Category | Typical Platform | Policy Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore | 3.8 (Gen Z 4.2) | 150–300 | Luxury goods and electronics | Shopee Live | Consumer protection laws increase trust by 20% |

| Indonesia | 4.5 (Gen Z 5.1) | 80–120 | Fashion and FMCG | TikTok Shop | E-commerce subsidy programs are stimulating young consumption |

| Thailand | 3.2 (Gen Z 3.5) | 100–200 | Home life and beauty | Lazada Live | The advertising law reduced the rate of complaints about false promotions by 30% |

| Cambodia | 1.2 (Gen Z 2.0) | <50 | Daily necessities and agricultural products | Local live-streaming platform | Cross-border policies need to be improved to restrict categories |

| Year | Impulse Buying Permeates | Total Amount of Impulse Purchases (in USD Billions) | Key Driver Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 12% | 25 | In the market cultivation period, the platform initially penetrated |

| 2022 | 35% | 120 | TikTok Shop in the ASEAN market |

| 2023 | 52% | 250 | Vietnam and Indonesia have eased cross-border e-commerce policies |

| 2024 | 63% | 380 | The ASEAN Economic Community deepens trade liberalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pei, Y.; Zhu, J.; Cao, J. Intergenerational Differences in Impulse Purchasing in Live E-Commerce: A Multi-Dimensional Mechanism of the ASEAN Cross-Border Market. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040268

Pei Y, Zhu J, Cao J. Intergenerational Differences in Impulse Purchasing in Live E-Commerce: A Multi-Dimensional Mechanism of the ASEAN Cross-Border Market. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040268

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Yanli, Jie Zhu, and Junwei Cao. 2025. "Intergenerational Differences in Impulse Purchasing in Live E-Commerce: A Multi-Dimensional Mechanism of the ASEAN Cross-Border Market" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040268

APA StylePei, Y., Zhu, J., & Cao, J. (2025). Intergenerational Differences in Impulse Purchasing in Live E-Commerce: A Multi-Dimensional Mechanism of the ASEAN Cross-Border Market. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040268