The Impact of Mobile Advertising Cue Types on Consumer Response Behaviors: Evidence from a Field Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cue Theory and Advertising Communication

2.2. Advertising Communication Within the Mobile Internet

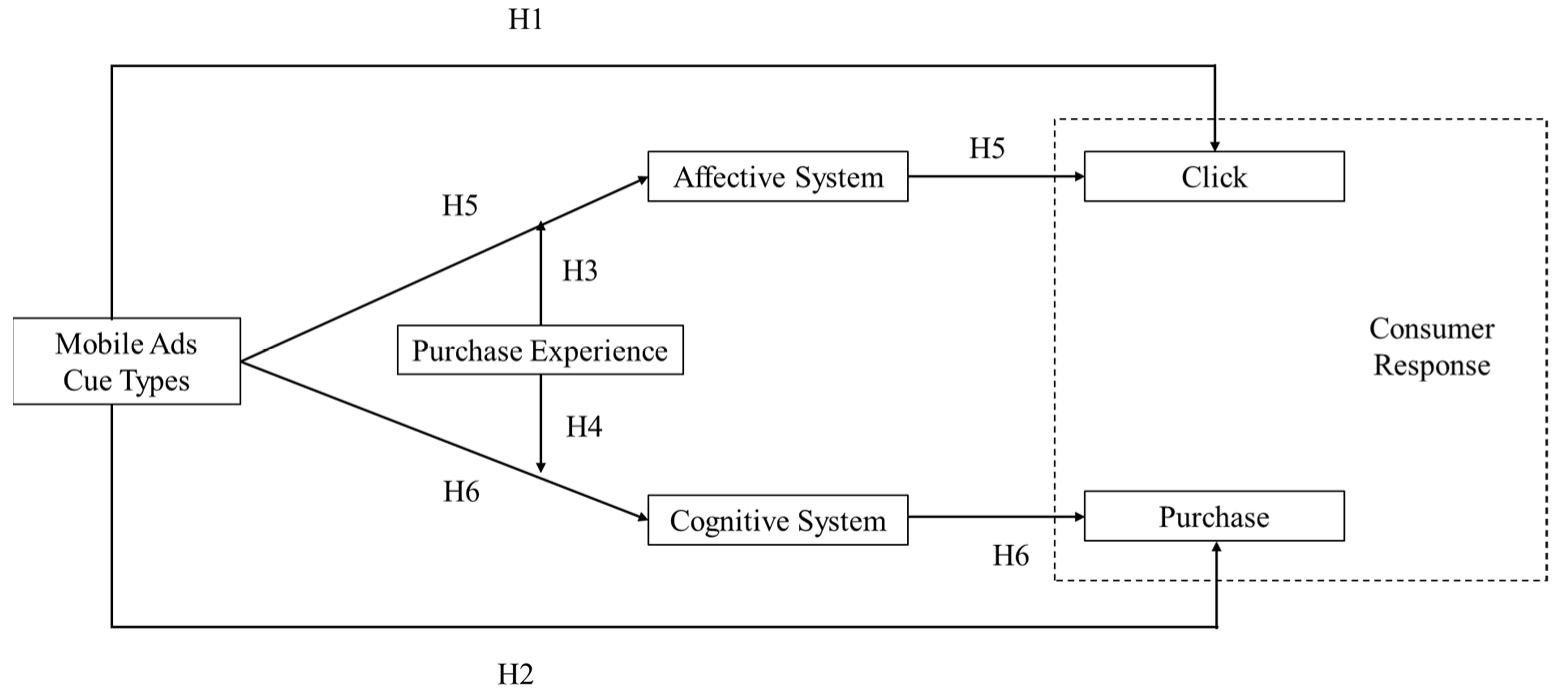

3. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

4. Experiment Design and Model Setup

4.1. Experiment Design

- (1)

- Experiment Overview. The experiment took place over a one-week period beginning 23 August 2019. During this time, the platform displayed banner adverts on both the homepage (i.e., the app’s landing interface) and the secondary advert content page (accessed via banner clicks). Adverts were presented continuously throughout the day to maximize user exposure.

- (2)

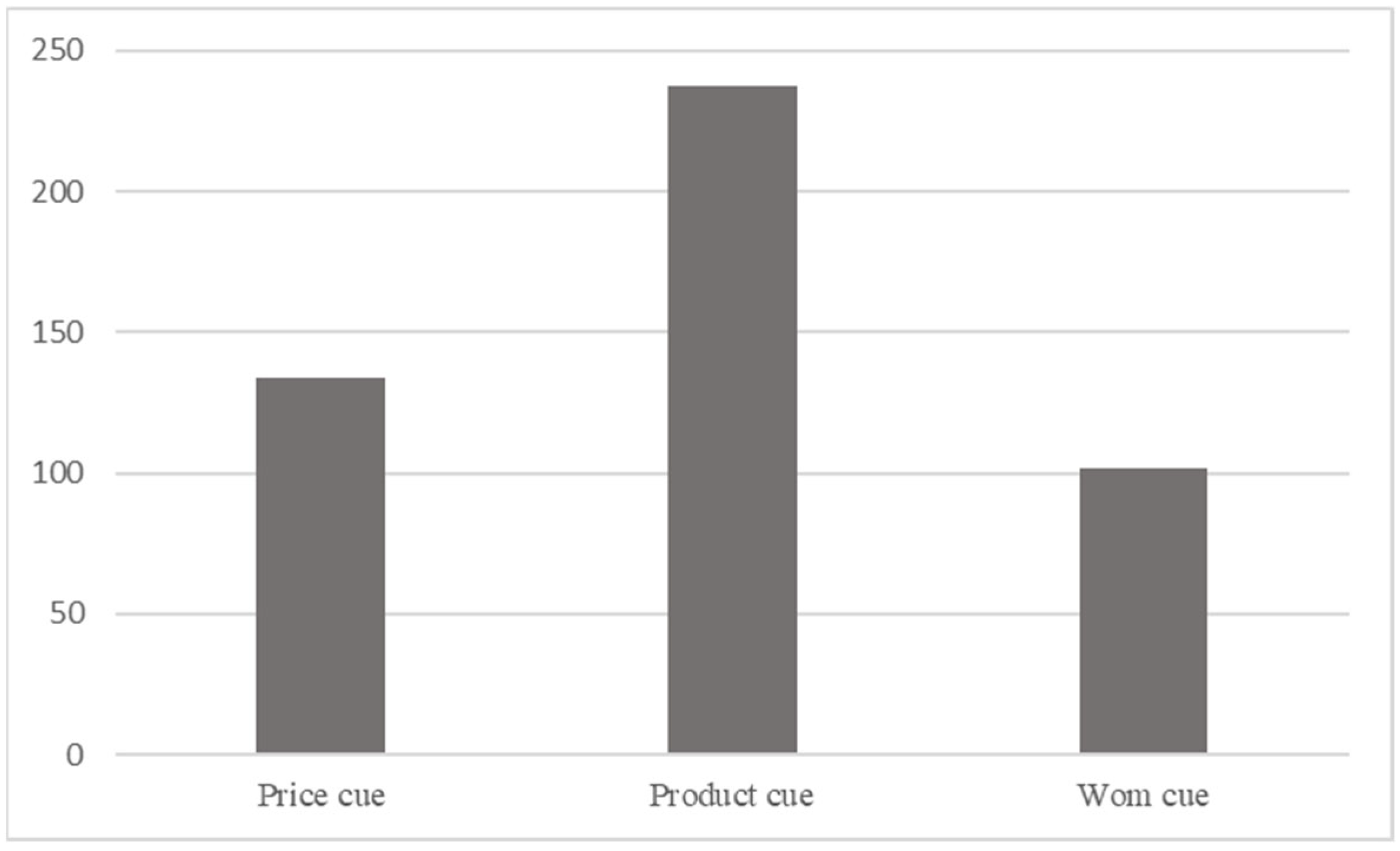

- Sample. To capture user behavior across different customer life cycle stages, we employed a stratified random sampling method. A total of 45,000 platform users were included in this study. To examine user responses across different customer life cycle stages, we implemented a stratified random sampling procedure in three steps:

- (3)

- Experiment Process. Users first encountered a top-level banner featuring one of the three cue types. Clicking the banner directed them to a second-level advert page, where cue-aligned content was reinforced via matching copy and small cue-specific icons. After viewing, users could choose whether to proceed with a purchase. All other experimental elements, such as course details, layout, and purchase mechanisms, were held constant to isolate cue effects.

- (4)

- Mobile Advert Design. The promoted product was a CPA pre-exam intensive training course. The top banner advertisement slogans displayed on this mobile app that represented price cues, product cues, and WOM cues, respectively, were as follows: “2019 Pre-exam Spotlight Intensive Training Class, $300 off per subject, and another 20% off for 2 or more subjects, grab it now!” “2019 Pre-Exam Spotlight Intensive Training Classes, taught by famous teachers, 45-h crash course to help you easily get to 60+, grab it now!” and “2019 Pre-Test Point Close Training Class, highly recommended by previous students, the majority of candidates’ choice, join the study immediately, grab it now!”

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Variables

4.3. Empirical Model

5. Results

5.1. The Impact of Cue Types on Clicks and Purchase

5.2. The Moderator of Consumer Experience on Clicks and Purchases

5.3. The Mediator of the Dual System

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Managerial Implications

6.4. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volkova, A.; Cho, H. Warm for fun, cool for work: The effect of color temperature on users’ attitudes and behaviors toward hedonic vs. utilitarian mobile apps. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Basic but Frequently Overlooked Issues in Manuscript Submissions: Tips from An Editor’s Perspective. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, B. The Impact of Mobile Social App Usage on Offline Shopping Store Visits. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Andrews, M.; Fang, Z.; Phang, C.W. Mobile Targeting. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Lee, C.T.; Lin, W.-Y. Meme Marketing on Social Media: The Role of Informational Cues of Brand Memes in Shaping Consumers’ Brand Relationship. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 588–610. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Luo, X.; Xu, B. Personalized Mobile Marketing Strategies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian, O.; Yoganarasimhan, H. Targeting and Privacy in Mobile Advertising. Mark. Sci. 2021, 40, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, R.; Symmank, C.; Seeberg-Elverfeldt, B. Light and Pale Colors in Food Packaging: When Does This Package Cue Signal Superior Healthiness or Inferior Tastiness? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.F. The Measurement of Information Value: A Study in Consumer Decision-Making; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuffer, A.; Phua, J. Stranger Danger? Cue-Based Trust in Online Consumer Product Review Videos. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 964–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuschke, N. An Analysis of Process-Tracing Research on Consumer Decision-Making. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 111, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, P.; Coveyou, M.T.; Behe, B.K. Visual Cues during Shoppers? Journeys: An Exploratory Paper. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.T. Advertising effects and effectiveness. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Gorlin, M. A Dual-System Framework to Understand Preference Construction Processes in Choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 23, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Park, J.; Park, H. How can I trust you if you’re fake? Understanding human-like virtual influencer credibility and the role of textual social cues. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 19, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.C.; Jacoby, J. Cue Utilization in the Quality Perception Process. In Proceedings of the Association for Consumer Research Conference; Association for Consumer Research: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, J.K.; Irmak, C. Having Versus Consuming: Failure to Estimate Usage Frequency Makes Consumers Prefer Multifeature Products. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, J.J.; Chiu, J.S.; Goldman, A. Physical Quality, Price, and Perceptions of Product Quality: Implications for Retailers. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.A. Obesity and the Built Environment: Changes in Environmental Cues Cause Energy Imbalances. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martin, S.; Camarero, C. A Cross-National Study on Online Consumer Perceptions, Trust, and Loyalty. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2012, 22, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Parker, P. Marketing Universals—Consumers Use of Brand-Name, Price, Physical Appearance, and Retailer Reputation as Signals of Product Quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Baek, Y.; Choi, Y.H. The Structural Effects of Metaphor-Elicited Cognitive and Affective Elaboration Levels on Attitude Toward the Ad. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, D.; Srivastava, J. Effect of Manufacturer Reputation, Retailer Reputation, and Product Warranty on Consumer Judgments of Product Quality: A Cue Diagnosticity Framework. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, M.; Park, M. Imagery Evoking Visual and Verbal Information Presentations in Mobile Commerce: The Roles of Augmented Reality and Product Review. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Luo, X.; Fang, Z.; Ghose, A. Mobile Ad Effectiveness: Hyper-Contextual Targeting with Crowdedness. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Gu, B.; Luo, X.; Xu, Y. Contemporaneous and Delayed Sales Impact of Location-Based Mobile Promotions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2015, 26, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X. Sunny, Rainy, and Cloudy with a Chance of Mobile Promotion Effectiveness. Mark. Sci. 2017, 36, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K.; Thusi, P. Understanding Consumers? Mobile Shopping Continuance Intention: New Perspectives from South Africa. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, Y.; Stephen, A.T.; Sarvary, M. Which Products Are Best Suited to Mobile Advertising? A Field Study of Mobile Display Advertising Effects on Consumer Attitudes and Intentions. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.W.; Chen, H.; Shah, S.J.; Shahzad, F.; Bano, S. Customization at a Glance: Investigating Consumer Experiences in Mobile Commerce Applications. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, B.T. Positive Spillovers and Free Riding in Advertising of Prescription Pharmaceuticals: The Case of Antidepressants. J. Polit. Econ. 2018, 126, 381–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z. The power of numbers: An examination of the relationship between numerical cues in online review comments and perceived review helpfulness. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Choi, K.; Han, S.P.; Cho, D. In-consumption information cues and online video consumption. MIS Q. 2024, 48, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E.; Srinivasan, S.; Riedl, E.J.; Skiera, B. The Impact of Online Display Advertising and Paid Search Advertising Relative to Offline Advertising on Firm Performance and Firm Value. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value—A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtola, K.; Luomala, H.T. Consumers’ Experience of Food Products: Effects of Value Activation and Price Cues. J. Cust. Behav. 2008, 7, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An Integrative Review of Sensory Marketing: Engaging the Senses to Affect Perception, Judgment and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.; Mischel, W. A Hot/Cool-System Analysis of Delay of Gratification: Dynamics of Willpower. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Hao, A. Effects of Vividness, Information and Aesthetic Design on the Appeal of Pay-per-Click Ads. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.; Mcfadden, D. Specification Tests for the Multinomial Logit Model. Econometrica 1984, 52, 1219–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical Mediation Analysis with a Multicategorical Independent Variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Ma, Z. How do consumers choose offline shops on online platforms? An investigation of interactive consumer decision processing in diagnosis-and-cure markets. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 16, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Li, B.; Liu, S. Mobile Targeting Using Customer Trajectory Patterns. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 5027–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title 1 | Variable | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | PURCHASE | Purchase or not: 1 = Purchase; 0 = otherwise |

| CLICK | Click on the ad or not: 1 = click; 0 = otherwise | |

| Independent Variable | PRICE | Is it a price-cue ad? 1 = yes; 0 = otherwise |

| WOM | Is it a WOM-cue ad? 1 = yes; 0 = otherwise | |

| Moderator | BUY | Registered users with purchase records: 1 = yes; 0 = otherwise |

| SIGN | Registered users without purchase records: 1 = yes; 0 = otherwise | |

| Control Variable | LEARN | Learning other courses in progress: 1 = yes; 0 = otherwise |

| DUR1 | Time spent on the first-level page | |

| DUR2 | Time spent on the ad-specific content page |

| PURCHASE | PRICE | WOM | BUY | SIGN | LEARN | DUR1 | DUR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PURCHASE | 1.000 | |||||||

| PRICE | −0.001 | 1.000 | ||||||

| WOM | −0.008 * | −0.500 * | 1.000 | |||||

| BUY | 0.029 * | −0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| SIGN | −0.014 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.500 * | 1.000 | |||

| LEARN | 0.016 * | −0.006 | −0.002 | 0.828 * | −0.414 * | 1.000 | ||

| DUR1 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.070 * | −0.040 * | 0.070 * | 1.000 | |

| DUR2 | 0.028 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 1.000 |

| CLICK | 0.001 * | 0.027 * | 0.005 | 0.018 * | −0.010 * | 0.010 | 0.014 * | 0.024 * |

| DV: CLICK | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| PRICE | 0.097 *** | 0.098 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| WOM | 0.833 *** | 0.833 *** | |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | ||

| BUY | 2.121 *** | 2.120 *** | 2.120 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| SIGN | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.977) | (0.930) | (0.957) | |

| LEARN | −0.132 ** | −0.133 ** | −0.133 * |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| LR chi2 | 10.09 | 12.63 | 14.73 |

| Log-Likelihood | −127.10 | −125.75 | −124.08 |

| Observation | 45,000 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

| DV: PURCHASE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| PRICE | −0.613 *** | −0.656 *** | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | ||

| WOM | −1.370 *** | −1.356 *** | |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | ||

| BUY | 2.261 *** | 2.258 *** | 2.256 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| SIGN | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| (0.969) | (0.981) | (0.987) | |

| LEARN | −0.770 | −0.770 | −0.772 |

| (0.091) | (0.092) | (0.092) | |

| DUR1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.824) | (0.813) | (0.810) | |

| DUR2 | −0.099 | −0.098 | −0.098 |

| (0.846) | (0.841) | (0.834) | |

| LR chi2 | 10.16 | 13.63 | 15.37 |

| Log-Likelihood | −147.30 | −145.57 | −144.70 |

| Observation | 45,000 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

| DV: PURCHASE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| PRICE | 0.092 *** | 0.091 *** | 0.091 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| WOM | 0.802 *** | 0.802 *** | 0.803 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| BUY | 2.088 *** | 2.088 *** | 2.092 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| BUY * PRICE | −0.027 *** | −0.026 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| BUY * WM | −0.019 *** | −0.019 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| SIGN | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.893) | (0.860) | (0.805) | |

| SIGN * PRICE | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (0.523) | (0.694) | ||

| SIGN * WOM | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (0.482) | (0.749) | ||

| LEARN | −0.131 ** | −0.131 ** | −0.132 * |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| LR chi2 | 10.11 | 12.97 | 15.03 |

| Log-Likelihood | −122.62 | −121.08 | −119.77 |

| Observation | 45,000 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

| DV: PURCHASE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| PRICE | −0.656 *** | −0.628 *** | −0.656 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| WOM | −1.346 *** | −1.315 *** | −1.315 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| BUY | 0.314 *** | 0.314 *** | 0.315 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| BUY * PRICE | 0.104 *** | 0.105 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| BUY* WM | 0.162 *** | 0.162 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| SIGN | −0.002 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| (0.903) | (0.912) | (0.978) | |

| SIGN * PRICE | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (0.332) | (0.973) | ||

| SIGN * WOM | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (0.122) | (0.996) | ||

| LEARN | −0.772 | −0.771 | −0.771 |

| (0.092) | (0.095) | (0.093) | |

| DUR1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.810) | (0.812) | (0.810) | |

| DUR2 | 0.984 *** | 0.985 *** | 0.985 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| LR chi2 | 15.37 | 17.10 | 17.37 |

| Log-Likelihood | −147.70 | −157.71 | −144.70 |

| Observation | 45,000 | 45,000 | 45,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Wu, B. The Impact of Mobile Advertising Cue Types on Consumer Response Behaviors: Evidence from a Field Experiment. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030244

Li Y, Deng X, Wu B. The Impact of Mobile Advertising Cue Types on Consumer Response Behaviors: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030244

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuan, Xiaoyu Deng, and Banggang Wu. 2025. "The Impact of Mobile Advertising Cue Types on Consumer Response Behaviors: Evidence from a Field Experiment" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030244

APA StyleLi, Y., Deng, X., & Wu, B. (2025). The Impact of Mobile Advertising Cue Types on Consumer Response Behaviors: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030244