Abstract

The development of Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has brought new ideas and opportunities to destination marketing. However, existing studies lack sufficient empirical research to explore the impact of AI anchors on tourists’ travel intentions. To fill this research gap, this study explores the influence of perceived anthropomorphism and perceived playfulness on tourists’ telepresence, inspiration, and travel intention in AI virtual anchor-based travel livestreaming. Through the analysis of 291 valid data sets, it was found that in AI virtual anchor-based travel livestreaming, perceived anthropomorphism positively affects telepresence but does not affect tourists’ inspiration. Playfulness positively affects tourists’ telepresence and inspiration in AI virtual anchor-based travel livestreaming. This study also found that neither perceived anthropomorphism nor perceived playfulness directly affects tourists’ travel intention, but both can be achieved through the mediating effect of telepresence. The findings provide empirical evidence of the value for tourism researchers and destinations in adopting AI technology for livestreaming.

1. Introduction

As an important technological innovation, Artificial intelligence (AI) is constantly driving changes in tourism experiences and marketing. It is increasingly argued that AI technology can significantly enhance destination marketing and enrich tourists’ experiences [1] as well as destination intentions [2]. Such empirical studies illustrate that AI technology can create new opportunities for tourist destinations to enhance their promotion. While AI has been increasingly adopted, livestreaming has also grown as a means to promote tourism destinations. Studies highlight how the interactivity, vividness, and authenticity in livestreaming can positively affect consumers’ travel intention [3], while celebrity streamers’ endorsements can enhance travel intention via informativity, entertainment, and interactivity [4]. However, few studies have focused on the impact of the combination of AI technology and travel livestreaming on consumer behavior.

Therefore, to fill this research gap, this study explores the influence of virtual anchors on tourists’ behaviors from the perspective of AI technology [5]. The concept of virtual anchors has increasingly attracted attention in livestreaming research [6,7,8]. Virtual anchors overcome the limitations of time and space, allowing for “7 × 24” hour continuous livestreaming, offering a high degree of flexibility and customization, enabling brands to tailor their appearance and communication style [9,10].

Destination marketers have begun to generate livestreaming content performed by an AI virtual anchor. This kind of virtual anchor is becoming a significant focus of attention in tourist destination marketing. When consumers have good virtual perception, the anthropomorphic characteristics of such virtual anchors may encourage the audience to pay greater attention to the streaming content [9]. This is because, essentially, the virtual anchor is imitating real-life anchors in terms of language, story-telling, and other aspects. Therefore, anthropomorphism appears to be an important prerequisite for understanding the impact of virtual anchors on consumer behavior [9,11]. However, in the context of livestreaming, how anthropomorphism affects tourists’ travel behavior remains an important research gap that needs to be filled.

When consumers watch virtual anchors conducting livestreaming promotions, the language and presentation style of the anchors can enhance the perception of the playfulness of the livestreaming. Playfulness is regarded as an important prerequisite factor to evaluate the perception and behavior of consumers in social media marketing [12,13]. For example, Yuan et al. have found that TikTok’s playfulness can positively influence consumers’ mental imagery, and can also positively mediate consumers’ attitudes and sharing intentions [14]. These studies emphasize that playfulness can positively influence consumer behavior in social media marketing. Nevertheless, in the context of livestreaming, how the playfulness of virtual anchors affects travel intention has only received limited attention.

When tourists are immersed in the story descriptions of virtual hosts, they may be attracted by the stories or the live content presented by the virtual hosts, thus forgetting time and concentrating on the live content. This phenomenon and perception can be explained from the perspective of presence, that is, tourists are completely immersed in the experience [15]. In addition, tourists can also draw inspiration from anthropomorphic perception or playfulness. Research suggests that inspiration often comes from external stimuli that evoke an emotional satisfaction [16]. Many empirical studies highlight the factors of presence and inspiration in understanding tourists’ psychology [17,18,19]. However, few studies have evaluated how perceived anthropomorphism and playfulness affect tourists’ travel intentions from the perspective of presence and inspiration as mediators, especially in the context of tourism livestreaming with virtual anchors.

To fill the above gaps in the literature, this study explores how, in the context of virtual anchor-based livestreaming, the perceived anthropomorphism and playfulness of the virtual anchor influence tourists’ travel intentions through telepresence and inspiration. Therefore, three specific research questions are raised. Firstly, what is the influence of perceived anthropomorphism and perceived playfulness on tourists’ telepresence? Secondly, what is the influence of perceived anthropomorphism and perceived playfulness on tourists’ inspiration? Finally, what is the mediating role of telepresence and inspiration between perceived anthropomorphism, perceived playfulness, and travel intention?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Travel Livestreaming (TLS) and AI-Based Anchors

Unlike prerecorded media, TLS enables a bidirectional communication channel where streamers capture and narrate tourist activities (e.g., visiting cultural sites, snorkeling, culinary experiences), and viewers actively shape the narratives through instant feedback, questions, and requests [20]. This interactivity makes TLS a transformative tool for tourism marketing. Despite the growing interest in TLS practices, limited attention has been given to how new technologies, such as AI, reshape viewer experiences and influence travel behavior in terms of TLS. This gap is notable given the operational challenges of TLS. Human anchors often struggle to meet real-time service demands from large audiences, resulting in unaddressed viewer requests and non-personalized interactions [21]. AI anchors, as a new form of anchor, may therefore be able to facilitate the relationship between streaming services and viewers [22]. By utilizing advanced technologies for perceptual and cognitive intelligence in vision, auditory, and natural language processing, AI anchors can mimic the physical and emotional traits of human anchors [7]. These technological advancements offer significant potential for addressing the challenges posed by massively individualized consumer demands. Consequently, the role of AI anchors in transforming viewers’ experiences in TLSs and shaping their travel intentions requires deeper examination.

2.2. Perceived Anthropomorphism

Perceived anthropomorphism involves assigning human-like qualities and traits to non-human entities to assess their similarity to humans [11]. Vinoi et al. suggest that anthropomorphism shapes the social bond between people and objects with human-like traits, reinforces consumers’ emotional engagement, encourages compelling interactions, and positively influences their travel decision-making and planning [23]. Ding et al. show that a high level of anthropomorphism helps consumers comprehend new information and unfamiliar situations by leveraging existing knowledge [24]. Nevertheless, several studies have found that anthropomorphism does not always lead to positive consumer outcomes. For example, Aggarwal and McGill highlighted that consumers might feel deceived by anthropomorphic brands that fail to live up to the human-like expectations created by their marketing, resulting in a loss of trust and potential damage to brand reputation [25]. To address these inconsistencies in previous findings, this study examines how anthropomorphism in AI-based anchors influences viewers’ perceptions and travel intentions, particularly within the context of livestreaming.

2.3. Perceived Playfulness

Perceived playfulness is a critical factor in understanding user engagement with emerging technologies, such as websites and AI-powered tools [26]. Playfulness reflects the extent to which an individual feels their attention is engaged by new technology, leading to experiences of curiosity and focus, and making the interaction inherently enjoyable or intriguing [27]. Research has shown that individuals who perceive higher levels of playfulness tend to have more favorable interactions with non-human entities [27]. Likewise, in the context of online shopping, Çelik found that higher levels of playfulness reduce cognitive barriers, making users more willing to navigate operational challenges [28]. Applying these insights to TLSs and exploring playfulness can help shed light on how viewers perceive and interact with AI anchors and how travel decision-making is shaped by dynamic interactions between them.

2.4. Telepresence

Telepresence is defined as a psychological state in which a user feels as though they are present in a virtual or remote environment, rather than their physical location [29]. This concept has been extensively examined in exploring the impact of various technologies on tourism and hospitality, including websites [30], short videos [31], and the metaverse [32]. Research indicates that telepresence significantly enhances the perceived utilitarian and hedonic performance of hotel websites, subsequently positively influencing consumer booking intentions [30]. Studies also highlight that the experiential value of metaverse travel enhances telepresence, allowing users to immerse themselves in the atmospherics of virtual destinations [32]. The rapid evolution of AI-integrated livestreaming necessitates updated research to address these issues. For example, Junior Ladeira et al. call for a more nuanced analysis of telepresence effects in various virtual platforms, considering their evolving features and implications for industry practices [33]. Therefore, there is a need to explore whether AI anchors’ characteristics affect viewers’ sense of “being there” in TLSs, and whether and how this telepresence impacts their travel intention.

2.5. Inspiration

Inspiration is described as a surge of beliefs driven by the influence of truth, beauty, and/or goodness [34]. Inspiration represents a particular form of intrinsic motivation, triggered by factors such as the nature of the source, including its compelling content and distinct features [35]. Individuals tend to feel more inspired when external stimuli evoke a sense of emotional fulfillment [16]. Research suggests that emerging e-commerce forms like TLSs can provide such stimuli by delivering engaging content and evoking emotional resonance, thereby enhancing viewers’ intentions to travel [35]. In TLSs, users are exposed to visually appealing and immersive video content, coupled with interactive experiences, which arouses feelings of enjoyment and well-being [36]. These affections, in turn, foster a state of flow, allowing viewers to emotionally connect with the destination when they visualize and imagine it [35]. Consequently, TLSs effectively stimulate viewers’ imagination about the portrayed destinations, thereby inspiring them to travel there [34]. With the increasing adoption of AI anchors, analyzing how this burgeoning form of TLSs reshapes viewers’ inspirational responses and subsequent travel intentions emerges as a critical research focus.

2.6. Hypotheses Development

Perceived anthropomorphism, that is, the extent to which users perceive human-like characteristics in non-human entities [11], may significantly enhance telepresence. Gao et al. found that virtual anchors’ likeability and animacy directly enhance consumers’ telepresence during livestreams [22]. The lifelike visual design and real-time interactivity create a perception of “being at the destination,” enhancing users’ sense of “arrival” in the virtual environment [37,38]. Kim et al. identified vividness (i.e., the richness of sensory information) and interactivity (i.e., the ability to engage with the environment) as critical factors in fostering telepresence [37]. These qualities can be effectively achieved by the anthropomorphic design of AI avatars [11]. Vividness is enhanced by lifelike visual esthetics such as humanoid appearance and expressive gestures. Interactivity is amplified through real-time responsiveness, including mimicking human anchors’ movements and dialog [39]. Collectively, these features can significantly deepen viewers’ sense of “being there” in the virtual environment. Hence, in the context of TLSs, anthropomorphic AI anchors may simulate the presence of viewers. Thus, a research hypothesis is proposed.

H1:

Perceived anthropomorphism positively affects telepresence in AI-based livestreaming.

Perceived playfulness refers to the extent to which users feel absorbed in virtual interactions, experience curiosity-driven exploration, and perceive the experience as inherently enjoyable or engaging [26]. According to flow theory [40], this perception may also contribute to telepresence by enhancing users’ flow experience in the mediated environment. Empirical evidence has shown that flow experiences in virtual environments, such as gaming contexts, are positively associated with telepresence [41]. Hsu et al. argue that the key components of perceived playfulness include experiences of curiosity, intense concentration, enjoyment, construct flow experiences [26]. Thus, when users perceive an environment as playful, their flow experience intensifies, further heightening their sense of telepresence.

H2:

Perceived playfulness positively affects telepresence in AI-based livestreaming.

The theory of planned behavior suggests that intentions are key predictors of actions [42]. Travel intentions are thus critical as they signal future visits to a destination [29]. Enhanced telepresence can boost travel intentions in various ways. Previous studies note that AI anchors that provide information and instantaneously interact with viewers can create immersive experiences, enhancing a sense of telepresence [43]. This enhanced telepresence positively affects experiential and instrumental value, evoking emotions such as enjoyment and satisfaction [29], further promoting the desire to physically visit a destination. Therefore, we posit that:

H3:

Telepresence positively affects travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

In TLSs, AI virtual anchors exhibit a high degree of embodiment through humanoid appearance, body movements, and language styles that mimic human tour guides, achieving form-like anthropomorphism [11]. Such anthropomorphism not only provides detailed product information but also makes interactions feel more natural and relatable, thus enhancing the sense of telepresence [44]. Spirit-like anthropomorphic qualities, such as likeability, friendliness, and kindness, reduce the psychological distance between viewers and AI anchors, enhancing viewers’ sense of human connection and emotional engagement [11]. This perceived bond fosters a vicarious immersive travel experience [45], creating feelings of “being there”. The resulting telepresence evokes positive emotions, like enjoyment and satisfaction [46], driving the desire to physically visit the destination. Therefore, we propose the following research hypothesis.

H4:

Telepresence mediates the relationship between perceived anthropomorphism and travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

Playfulness enhances telepresence by intensifying users’ flow experience in a mediated environment, characterized by curiosity, intense concentration, and enjoyment [26]. When users perceive an environment as playful, their flow experience deepens, thereby enhancing their sense of telepresence [41]. This enhanced telepresence, stemming from the flow state, can lead to a positive evaluation of the travel experiences [47], reinforcing the intention to visit the depicted destination. The following hypothesis is thus proposed:

H5:

Telepresence mediates the link between perceived playfulness and travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

Inspiration is often perceived as an emotional resonance that instills individuals with beliefs drawn from authenticity, goodness, or beauty [34]. Customer inspiration theory describes inspiration as a shift from being “inspired by” to an “inspired to” state [48]. In terms of antecedents, especially during the “inspired by” phase, this theory posits that the characteristics of the inspiration source are crucial in determining customer inspiration. In the context of TLSs, AI anchors can serve as virtual personal assistants, delivering inspirational content through highly tailored, innovative, and efficient travel recommendations [49]. Furthermore, AI anchors appeal to viewers’ imaginations by exhibiting anthropomorphic gestures, facial expressions, and voices [11]. These techniques can generate a flow state that encourages viewers to envision themselves in the portrayed destination, thereby stimulating imaginative thinking and inspirational reaction [35]. Thus, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H6:

Perceived anthropomorphism positively affects inspiration in AI-based livestreaming.

According to Moon and Kim, playfulness involves the extent to which individuals feel engaged, curious, and find interactions enjoyable during online activities [50]. Hsu et al. highlights that such playful activities can lead to a flow state, whereby concentration, curiosity, and enjoyment are heightened, appealing to imagination and consequently fostering inspiration [26]. In the context of TLSs, playfulness may lead viewers to appraise interactions with AI anchors as positive and intriguing, thereby increasing their openness to inspiration. When viewers feel joy and amusement, they become more receptive to novel ideas and experiences, resulting in stronger inspiration. Thus, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H7:

Perceived playfulness positively affects inspiration in AI-based livestreaming.

Inspiration is described as a motivational state that prompts a potential tourist to turn newfound travel ideas into reality in tourism [51]. It is a temporary state that bridges the gap between deliberation and action. The transmission model of inspiration suggests that individuals first become aware of new or improved possibilities and then feel compelled to actualize these ideas, progressing to the “inspired-to” stage [16]. Assiouras et al. found that virtual reality can enhance travel inspiration by informing viewers of potential travel options through vivid images and a high quality of elaboration, thereby increasing the intention to visit [52]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H8:

Inspiration positively affects travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

Assiouras et al. suggest that the vividness conveyed by vibrant anthropomorphic qualities fosters quasi-trial experiences and stimulates mental imagery (i.e., the mental visualization of a depicted destination) [52]. This imaginative engagement sparks consumers’ inspiration, converting positive appraisals of virtual travel experiences into actionable travel intentions. Likewise, Kim argues that human-like presentation skills and personal charisma make AI anchors feel more attractive, professional, and trustworthy [53]. These positive appraisals, in turn, enhance viewers’ inspirational experiences and encourage their travel intentions [35]. Thus, we proposed a mediating hypothesis.

H9:

Inspiration mediates the relationship between perceived anthropomorphism and travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

Playful interactions create a flow state where viewers are immersed in the content, heightening their emotional and imaginative engagement [26]. Furthermore, playful interactions reduce cognitive barriers and operational concerns, making the travel-related content more accessible and appealing [28]. The perceived ease of engagement further enhances approach motivations, inspiring viewers to explore and act on travel ideas presented by AI anchors. As a result, inspiration mediates the relationship between perceived playfulness and travel intention.

H10:

Inspiration mediates the link perceived playfulness and travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

Zhang and Wang found that virtual anchors with realistic human-like features are perceived as more competent and knowledgeable, enhancing consumer trust and positive attitudes, thereby significantly increasing purchase intentions [54]. Zhong et al. suggest that incorporating human-like emotional traits, such as the warmth and experientiality associated with female robots, into algorithms can reduce the perceived dehumanization of these robots [7]. These anthropomorphic features build emotional trust and encourage consumer continued use of AI livestreaming. Therefore, we propose that perceived anthropomorphism may positively impact viewers’ intention to visit.

H11:

Perceived anthropomorphism positively affects travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

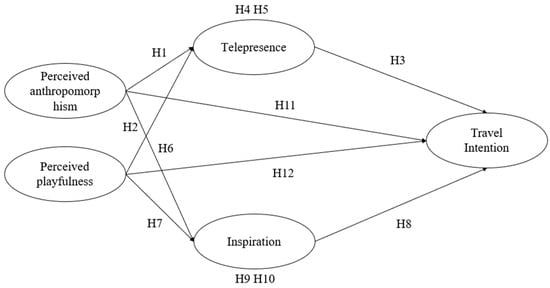

Moon and Kim emphasized the critical role of playfulness on the adoption of the World-Wide-Web, demonstrating its significant positive effect on users’ willingness to use the system [50]. Similarly, Ahn et al. highlighted that users who experience playfulness while interacting with online platforms are more engaged and more likely to continue their interactions, shaping future usage intentions [27]. Based on these findings, we propose that perceived playfulness may positively influence travel intention. Furthermore, Figure 1 presents the relationships between the identified variables.

Figure 1.

Research model.

H12:

Perceived playfulness positively affects travel intention in AI-based livestreaming.

3. Research Method

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire used for data collection in this study consists of three sections. In the first part of the questionnaire, there is a research introduction and a screening question. Participants were clearly informed of the purpose of the research, which is only for academic research and does not involve loss of personal privacy. Such information provision is also regarded as effectively reducing the potential for common method bias [55]. A screening question was provided, which asked whether participants had watched the livestreaming of the travel destination by an AI-based virtual anchor in the previous three months. The period of three months was set in reference to previous online survey research on livestreaming [3], in order to enhance the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. If a participant answered “no”, the survey was regarded as invalid.

The second part of the questionnaire contains measurable items for five research constructs. All measurable items used in the research are selected from measurable items that have been empirically demonstrated in previous studies. To evaluate perceived anthropomorphism, this study utilizes the measurement from Vinoi et al. [23]. The measurable items of Lin et al. [56] were used to evaluate playfulness. Telepresence was examined by the measurable items of Zhu et al. [31]. Inspiration was studied using the measurable items of Cheng et al. [34], and travel intention was evaluated by the measurable items of Fakharyan et al. [57]. The measurable items of the current questionnaire are evaluated using a 7-subscale from 1 to 7, that is, from “very disagree” to “very agree”. The last part of the questionnaire reported the participants’ personal background, such as age, educational background, monthly income, and gender. Given that the target group is Chinese tourists, the survey translation was completed by two scholars who are familiar with both Chinese and English. In June 2025, a pilot survey was conducted on a total of 30 pre-survey data samples. These participants indicated that they could clearly understand the content of the questionnaire. Therefore, the current version of the questionnaire was used for formal data collection, and the 30 pre-survey samples have also been presented in the formal analysis.

3.2. Data Collection

This research used a professional online questionnaire company for data collection. Online questionnaires are the main form of data collection on travel livestreaming [58]. They are characterized by fast response efficiency and the ability to complete normal data collection in a short period of time. Use of online questionnaires can expand the background of the samples [59]. Based on these advantages, the collection method of online questionnaires has been adopted by travel livestreaming research and recognized by leading journals [60,61]. This study uses the services of Tencent Questionnaire for data collection. Tencent Questionnaire is one of China’s largest online survey companies, and all users are registered. Each user can only fill out an online questionnaire once, therefore helping to ensure the quality of the survey data [55]. Data collection was undertaken 13–18 June 2025. A total of 400 participants completed the questionnaire. Excluding those who did not meet the screening criteria, such as not having watched AI virtual hosts’ travel livestreams in the past three months, a total of 291 valid questionnaires were used for the current data analysis.

4. Findings

The current research selects partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) primarily based on the following points. Firstly, PLS-SEM is suitable for a complex model, considering this study has 12 research hypotheses. Secondly, the current sample consists of 291 valid samples. This sample is relatively small, and PLS-SEM is suitable for the analysis of small sample data. Therefore, PLS-SEM is used for current data analysis.

4.1. Sample Background

As shown in Table 1, 291 participants were used for data analysis in this study, consisting of 110 males (37.8%), and 181 females (62.2%). The group with the highest monthly income earned CNY 4001–6000 a month, accounting for 30.9% of respondents. 63.2% of respondents hold a bachelor’s degree as their highest qualification. Finally, the group with the largest age concentration is aged 26–30 years old, accounting for 31.6% of respondents.

Table 1.

Sample background (n = 291).

4.2. Reliability and Validity of the Model

All the current Factor loadings exceed 0.7 (see Table 2) and, following PLS analysis, all the composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha are greater than 0.7, and the AVE exceeds 0.5 (see Table 3). Therefore, the current model achieves acceptable reliability and validity [62]. The Fornell–Larker criterion was adopted in the current study to examine the discriminative validity of the current model. The square roots of all AVEs are greater than the values of the planes where they are located; therefore, the current model has obtained sufficient discriminative validity [62]. Finally, to evaluate the predictability of the model, we adopted the metric of R square. All R Squares were greater than 0.26, so the model possesses sufficient predictability.

Table 2.

Factor loading of measurable items.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity of the model.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

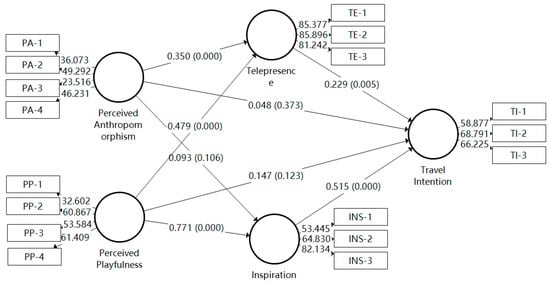

To evaluate the potential for common method bias, this study adopted the approach recommended by scholars for PLS-SEM models (e.g., Ji et al. [63]). This involved introducing a randomly generated variable (with values between 0 and 1) as a dependent variable. The subsequent PLS analysis indicated that all inner variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 3. This finding suggests that common method bias was not detected [63] and, therefore, it is unlikely to affect the conclusions of this study. To evaluate the conclusion of the current model, this study adopted Bootstrapping with 5000 samples for data analysis. The research found that, except for perceived anthropomorphism having no significant effect on inspiration (0.093 ns) and travel intention (0.048 ns), and playfulness having no significant effect on travel intention (0.147 ns), all other research hypotheses were significantly valid. Perceived anthropomorphism positively influences telepresence (0.350 ***). Playfulness positively influences telepresence (0.479 ***) and inspiration (0.771 ***). Telepresence and inspiration positively influence travel intention (0.229 ** and 0.515 ***). Table 4 and Figure 2 present the results of the PLS-SEM hypothesis analysis.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis development.

Figure 2.

Results of PLS-SEM. Notes: PA = perceived anthropomorphism; PP = perceived playfulness; TE = telepresence; INS = inspiration; TI = travel intention.

4.4. Mediating Role Testing

To evaluate the mediating role of telepresence and inspiration, bootstrapping with 5000 samples was used for analysis. The study found that except for inspiration, there was no significant mediating role between perceived anthropomorphism and travel intention (Table 5). All other mediated hypotheses hold true. For example, telepresence positively mediates perceived anthropomorphism, playfulness, and travel intention. Inspiration positively mediates playfulness and travel intention.

Table 5.

Mediating roles of telepresence and inspiration.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

This study explores the relationship between perceived anthropomorphism, perceived playfulness, and telepresence through SEM analysis. Research has found that both perceived anthropomorphism and perceived playfulness have a positive impact on telepresence. Telepresence describes a psychological state in which an individual feels as if they are existing in a mediating environment, thereby achieving an immersive perception [37,64]. In the context of livestreaming by virtual anchors, visitors can immerse themselves in this digital technology, with perceived anthropomorphism emphasizing the degree of perception of users in the experience of non-human entities [11]. Virtual anchors, although products of virtual technology, still possess human characteristics. Therefore, this anthropomorphism can also help immerse consumers in livestreaming, which might explain why anthropomorphism positively influences consumers’ telepresence. Furthermore, when consumers are immersed in the presentation of virtual anchors, the interactivity and the degree of interest will further affect the consumers’ playfulness experience. This is because, in the context of virtual livestreaming, the virtual anchor can enhance the telepresence of visitors through gamified interaction, vibrant visual effects, and interesting storytelling [65]. Therefore, this may help explain why playfulness positively affects tourists’ perception of telepresence.

Secondly, this study explored the relationship between perceived anthropomorphism, perceived playfulness, and inspiration. The results show that perceived anthropomorphism has no positive impact on tourists’ inspiration, but perceived playfulness has a positive impact on tourists’ inspiration. In the context of virtual anchors’ livestreaming, inspiration is understood as consumers’ emotional responses to the interaction and experience process with AI anchors. In virtual livestreaming, virtual anchors can enhance users’ travel suggestions through innovative and personalized recommendations [49]. However, with the development of technology, consumers may have easier access to more AI products than ever before. Therefore, excessive experience with AI products may lead to potential problems of product homogenization, which in turn may affect consumers’ interest. Most importantly, the construction and update of AI corpora require continuous investment of funds and time. This is because virtual anchors can generate personalized perceptions by imitating the actions and expressions of real anchors, mainly based on the live content generated by the corpus. However, the quality of anthropomorphism depends on the nature of different AI corpora. The content presented by AI anchors of different technical levels varies, presenting a potential problem of product homogeneity, which may help explain why there is no significant connection between perceived anthropomorphism and tourists’ inspiration.

Thirdly, this study also evaluated the mediating role of telepresence. This study found that although perceived anthropomorphism has no significant impact on tourists’ travel intentions, Telepresence plays a very significant mediating role between them. In the livestreaming of virtual anchors, although AI is the basis of virtual anchors, from the anthropomorphic perspective, it is still imitating human appearance, body movements, and language styles [11]. Telepresence emphasizes an immersive perception when tourists are completely attracted and immersed in this virtual livestreaming environment. AI virtual humans have similarities to real-life anchors, meaning that tourists can obtain immersive perception through realistic behaviors [22]. When consumers have sufficient telepresence, telepresence can also significantly enhance tourists’ travel intention. Therefore, telepresence plays an important mediating role between perceived anthropomorphism and travel intention.

Fourth, the research found that telepresence significantly mediates playfulness and tourists’ travel intention. In the context of virtual livestreaming, Hsu et al. argued that key components of playfulness include curiosity, high concentration, and an enjoyable experience [26]. In virtual livestreaming, visitors can perceive a strong sense of playfulness. Therefore, the telepresence of visitors significantly increases after they gain playfulness. However, not every consumer can sense the playfulness in virtual experiences. For example, some playfulness may be favored by young consumers, but not older consumers. Therefore, the results indicate that although these interesting elements can affect consumers’ telepresence perception, they do not necessarily directly influence their travel intention, although telepresence positively mediates playfulness and travel intentions.

Finally, the research found that inspiration has no significant mediating effect between perceived anthropomorphism and travel intention, but it does have a mediating effect between perceived playfulness and travel intention. As noted above, although AI corpora can constantly update the anthropomorphic perception of livestreaming anchors, the anthropomorphic perception of livestreaming anchors does not necessarily always arouse the interest of consumers. Previous research has shown that perceived anthropomorphism gestures, facial expressions, and human personality traits can evoke emotional resonance and imaginative audience engagement [11]. However, in this study, the age groups of consumers were different, and the extent to which they gained inspiration also varied. Therefore, this might explain why inspiration does not play an important mediating role in perceiving anthropomorphism and travel intentions. However, unlike the anthropomorphic characteristics of perception, the playfulness aspect may attract consumers’ interest due to the interesting visuals and the rich and diverse forms of expression, thereby influencing inspiration. Ultimately, when consumers gain positive inspiration, it prompts their travel intentions to change positively. Therefore, inspiration has a significant mediating effect between playfulness and travel intention.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study offers some theoretical contributions for future research to consider and enrich work on AI virtual anchors and TLS. Firstly, this study has expanded the application of perceived anthropomorphism in AI-based livestreaming. Previous research has argued that perceived anthropomorphism is an important variable to connect consumers’ evaluations and preferences, and guide consumers’ emotional participation, ultimately influencing consumers’ travel decisions [23,24]. However, these studies are different from those conducted in a virtual environment, especially when virtual anchors are used for marketing. Although virtual anchors may seem very similar to humans, they are not exactly like them, and their nuanced differences may affect consumers’ purchasing decisions. This study expands the development of this concept in virtual tourism livestreaming by exploring the influence of perceived anthropomorphism on tourists’ inspiration, telepresence, and travel intention.

Secondly, this research has expanded the application of playfulness in virtual travel livestreaming. Playfulness is regarded as a key factor for understanding human relationships with emerging technologies [26]. Previous work suggests that when consumers obtain a high degree of perceived playfulness, this will positively affect consumers’ interaction with non-human entities [27]. In virtual tourism livestreaming, the findings of this study show that when consumers see virtual anchor’s livestreaming tourism products, they become interested in the performance of the anchor due to the rich forms of expression. This finding provides a foundation for future scholars to explore the value that playfulness plays in tourism livestreaming.

Thirdly, this study expands the application of the telepresence concept in tourism livestreaming. Research has suggested that telepresence is a key factor for understanding tourists’ travel intentions in the virtual environment [30], especially when tourists gain immersive perceptions in these virtual contexts [15]. Therefore, when tourists perceive telepresence, they tend to provide positive feedback, such as the intention to continue traveling [32]. Considering the gradual development of virtual anchors based on AI technology, this study provides a valuable theoretical basis for future research on telepresence theory in virtual livestreaming.

Finally, this study also expands the development of inspiration in AI-based livestreaming. Previous studies have pointed out that when external stimuli evoke emotional satisfaction, individuals tend to receive sufficient inspiration [16]. Research on human anchor-based livestreaming suggests that tourists’ positive emotion is stimulated when they are exposed to video content with visual appeal, immersion, further enhancing their interactive experience and arousing travel intention [34,36]. However, it is unclear whether consumers will still be so influenced by external stimuli when the anchor is a virtual person. Therefore, this study explored inspiration in the context of virtual anchors to provide a better understanding of the relationship between external stimuli and tourist behavior.

5.3. Practical Contributions

This study provides certain practical inspirations for tourism livestreaming operators. Firstly, this study has found that perceived anthropomorphism positively affects tourists’ telepresence but has no significant impact on tourists’ inspiration. Therefore, the anthropomorphism feature construction of virtual anchors needs to be enhanced. For instance, by leveraging high-definition and intelligent databases, the authenticity and experience of virtual anchors can be updated in a timely manner, thereby enhancing their real-time performance, giving people a sense of reality, and ultimately improving the perception of anthropomorphism and telepresence.

Secondly, although anthropomorphism has no impact on inspiration, livestreaming operators can consider using more realistic video and livestreaming production machines to make the livestreams of virtual anchors more authentic, thereby enhancing tourists’ inspiration. To enhance tourists’ perception of inspiration, it is recommended to incorporate a large amount of corpus during virtual human livestreaming to enrich virtual anchor content, making the presentation more vivid, allowing tourists to feel that the presentation is more like that of a real person, and ultimately inspiring consumers’ behavior.

Third, this research has found that the AI playfulness of virtual anchors can significantly enhance tourists’ telepresence and inspiration. This insight may encourage new ways of engendering interest in virtual anchors and travel livestreaming by, for instance, encouraging a greater degree of interaction with virtual anchors. This interaction has also been confirmed by previous studies to significantly enhance tourists’ perception of telepresence [31]. Therefore, livestreaming managers should consider collaborating with destination partners to better present the stories of some locations in the travel destination through virtual anchors, allowing the audience to immerse themselves and gain further inspiration. For instance, using a professional animation production company to provide different perspectives as to how virtual anchors can make the presentation of scenes more direct and realistic.

Finally, this research found that perceived anthropomorphism and playfulness do not directly affect tourists’ travel intentions; they both need to be accomplished through telepresence. Therefore, enterprises should consider improving the quality of presentation by working with professional media, AI companies, and destination marketing organizations to make the perception of AI virtual anchors more immersive and richer, as well as to better express the history and culture of local tourist destinations. For many tourist destinations, a good AI virtual anchor should be integrated into the local culture and history. Virtual anchors who can convincingly convey local history and culture can make consumers feel that they are not just listening to the anchor’s sales, but more importantly, they know the history and culture of the destination. These methods can significantly enhance consumers’ telepresence and ultimately influence their consumption behavior.

5.4. Limitations and Future Studies

The current research has some limitations for future studies to consider. Firstly, the current research only explores the influence of virtual anchors on tourists’ travel intentions and does not compare it with human anchors. Therefore, future research can consider using comparative experimental designs to evaluate the different influences of virtual anchors and human anchors on tourists’ travel intentions. Second, from the perspective of sample selection, the current participants are still mainly young consumers. Future research can explore the attitudes of consumers of different age groups towards AI virtual livestreaming. Finally, this research only focuses on Chinese tourists. Future studies can adopt the current research model to test the attitudes of tourists from other cultural backgrounds towards AI virtual anchors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and Z.Q.; methodology, L.T.; validation, L.T.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; resources, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z. and Z.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.M.H. and Z.Q.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, C.M.H.; project administration, Z.Z. and L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. and Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Baiyulan Talent program Pujiang Project (Project No. 24PJC064), and the project of Artificial Intelligence-Driven Research Paradigm Reform and Empowering Discipline Leap Plan of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (Project No. KY2025-ZX-RGZN-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

We confirmed that all procedures of this study adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm, accessed on 29 July 2025) promulgated by China. Furthermore, this study is not medical research and does not involve human experimentation as defined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study uses anonymized data to conduct research, causing no harm to the human body and involving neither sensitive personal information, thus, ethical approval is not required for this study based on local regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, J. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology in destination advertising: The impact of video-based destination anthropomorphism on destination image. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 35, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-García, P.-M.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Polo-Peña, A.I. Virtual tours: The effect of artificial intelligence and intelligent virtual environments on behavioral intention toward the tour and the tourist destination. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wu, M.; Liao, J. The impact of destination live streaming on viewers’ travel intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, D.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, B. How celebrity endorsement affects travel intention: Evidence from tourism live streaming. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Supervising or assisting? The influence of virtual anchor driven by AI-human collaboration on customer engagement in live streaming e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 25, 3047–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chung, W. Digital emotional bonds: How virtual anchor characteristics drive user purchase intention in livestreaming e-commerce. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251342981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Wu, F.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y. Navigating the human-digital nexus: Understanding consumer intentions with AI anchors in live commerce. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-P.; Xin, L.; Wang, H.; Park, H.-W. Effects of AI virtual anchors on brand image and loyalty: Insights from perceived value theory and SEM-ANN analysis. Systems 2025, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Cao, L.; Zhou, J. Is the anthropomorphic virtual anchor its optimal form? An exploration of the impact of virtual anchors’ appearance on consumers’ emotions and purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Gu, X.; Xu, N.; Zheng, J.; Wu, W.; Jiang, M.; Xue, N. Live streaming mode selection strategy under the sackground of virtual anchor supplementation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shao, B.; Yang, X.; Kang, W.; Fan, W. Avatars in live streaming commerce: The influence of anthropomorphism on consumers’ willingness to accept virtual live streamers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 156, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.-M. Unlocking trust dynamics: An exploration of playfulness, expertise, and consumer behavior in virtual influencer marketing. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Baek, T.H. Expertise and playfulness of social media influencers. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2025, 46, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Surachartkumtonkun, J.; Shao, W. Playful TikTok videos: Investigating the role of mental imagery in customers’ social media sharing and destination attitude. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Hall, C.M.; Fong, L.H.N.; Liu, C.Y.N.; Koupaei, S.N. Vividness, narrative transportation, and sense of presence in destination marketing: Empirical evidence from augmented reality tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrash, T.M.; Elliot, A.J. Inspiration as a psychological construct. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 1115–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.M.B.; Pham, X.L.; Truong, G.N.T. The influence of source credibility and inspiration on tourists’ travel planning through travel vlogs. J. Travel Res. 2025, 64, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Io, M.-U.; Hall, C.M.; Ngan, H.F.B.; Peralta, R.L. Exploring the influence of augmented reality on tourist word-of-mouth through the lens of museum tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2025, 20, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, D. Understanding consumers’ motivations to view travel live streaming: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, N.; He, Y.; Liu, D.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, G. Artificial intelligence (AI) assistant in online shopping: A randomized field experiment on a livestream selling platform. Inf. Syst. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jiang, N.; Guo, Q. How do virtual streamers affect purchase intention in the live streaming context? A presence perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoi, N.; Shankar, A.; Abdullah Alzeiby, E.; Gupta, P.; Agarwal, V. Unveiling customer intentions: Exploring factors driving engagement with hospitality virtual influencers. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2025, 34, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Lee, R.H.; Legendre, T.S.; Madera, J. Anthropomorphism in hospitality and tourism: A systematic review and agenda for future research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; McGill, A.L. Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C.; Chen, M.-C. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intention: Perceived playfulness and perceived flow as mediators. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2012, 10, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Ryu, S.; Han, I. The impact of Web quality and playfulness on user acceptance of online retailing. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, H. Influence of social norms, perceived playfulness and online shopping anxiety on customers’ adoption of online retail shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Gurrea, R.; Flavián, C. Telepresence in live-stream shopping: An experimental study comparing Instagram and the metaverse. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongsakul, V.; Ali, F.; Wu, C.; Duan, Y.; Cobanoglu, C.; Ryu, K. Hotel website quality, performance, telepresence and behavioral intentions. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N.; Li, X.; Buhalis, D.; Chen, H. Short video marketing in tourism: Telepresence, celebrity attachment, and travel intention. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. How does the metaverse travel experience influence virtual and actual travel behaviors? Focusing on the role of telepresence and avatar identification. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior Ladeira, W.; de Oliveira Santini, F.; Rasul, T.; Hasan Jafar, S.; Carlos De Oliveira Rosa, J.; Frantz, B.; Zandonai Pontin, P.; Antonio Lampert Dornelles, L. Telepresence in tourism and hospitality: A meta-analytic review of virtual environment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhang, L. Seeing destinations through vlogs: Implications for leveraging customer engagement behavior to increase travel intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3227–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, L.; Feng, W.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y. Is tourism live streaming a double-edged sword? The paradoxical impact of online flow experience on travel intentions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, G. The influence mechanism of travel livestreaming’s (TLS) characteristics on users’ tourism well-being. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, M.; Park, M.; Yoo, J. How interactivity and vividness influence consumer virtual reality shopping experience: The mediating role of telepresence. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Gu, G. How travel live streaming affects viewers’ travel intentions: The mediating role of sense of presence and perceived usefulness. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, 70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Y. Factors influencing users’ watching intention in virtual streaming: The perspective of flow experience. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikzentmihaly, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Faiola, A.; Smyslova, O. Flow experience in Second Life: The impact of telepresence on human-computer interaction. In Online Communities and Social Computing; Ozok, A.A., Zaphiris, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 574–583. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Dastane, O.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Jha, S. The future of live-streaming commerce: Understanding the role of AI-powered virtual streamers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 37, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Khynevych, R.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y. Effect of anthropomorphism and perceived intelligence in chatbot avatars of visual design on user experience: Accounting for perceived empathy and trust. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1531976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Tan, G.W.-H. Empowerment to commitment: How live-streaming atmosphere and relational bonds drive impulse consumption? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 19, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Tang, J.; Ye, S.; Tan, X.; Wei, W. Virtual reality in destination marketing: Telepresence, social presence, and tourists’ visit intentions. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.-K. Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: Effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, T.; Rudolph, T.; Evanschitzky, H.; Pfrang, T. Customer inspiration: Conceptualization, scale development, and validation. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.I.; Wong, I.A.; Zhang, C.J.; Liang, Q. Generative AI inspiration and hotel recommendation acceptance: Does anxiety over lack of transparency matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Wang, D.; Kirillova, K. Travel inspiration in tourist decision making. Tour. Manag. 2022, 90, 104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Giannopoulos, A.; Mavragani, E.; Buhalis, D. Virtual reality and mental imagery towards travel inspiration and visit intention. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Parasocial interactions in digital tourism: Attributes of live streamers and viewer engagement dynamics in South Korea. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. The effect of virtual anchor appearance on purchase intention: A perceived warmth and competence perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 34, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wu, D.C.W.; Hall, C.M.; Fong, L.H.N.; Koupaei, S.N.; Lin, F. Exploring non-immersive virtual reality experiences in tourism: Empirical evidence from a world heritage site. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Tseng, H.-T.; Shirazi, F.; Hajli, N.; Tsai, P.-T. Exploring factors influencing impulse buying in live streaming shopping: A stimulus-organism-response (SOR) perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1383–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharyan, M.; Jalilvand, M.R.; Elyasi, M.; Mohammadi, M. The influence of online word of mouth communications on tourists’ attitudes toward Islamic destinations and travel intention: Evidence from Iran. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Huang, S. Live streaming in hospitality and tourism: A hybrid systematic review and way forward. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 1924–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J. How the destination short video affects the customers’ attitude: The role of narrative transportation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Huo, Y.; Luo, P. What drives impulsive travel intention in tourism live streaming? A chain mediation model based on SOR framework. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Fu, S. Tourism live streaming: Uncovering the effects of responsiveness and knowledge spillover on travelling intentions. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 1126–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, E.; Rahman, S.M.; Wilden, R.; Lin, N.; Harrison, N. Leveraging Customer Knowledge Obtained Through Social Media: The Roles of R&D Intensity and Absorptive Capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.R. Creating virtual product experiences: The role of telepresence. J. Interact. Mark. 2003, 17, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapis, A.; Guckelsberger, C.; Zhu, J.; Harteveld, C.; Kriglstein, S.; Denisova, A.; Gow, J.; Preuss, M. Designing for playfulness in human-AI authoring tools. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG ‘23), Lisbon, Portugal, 12–14 April 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).