Digital Selves and Curated Choices: How Social Media Self-Presentation Enhances Consumers’ Experiential Consumption Preferences

Abstract

1. Introduction

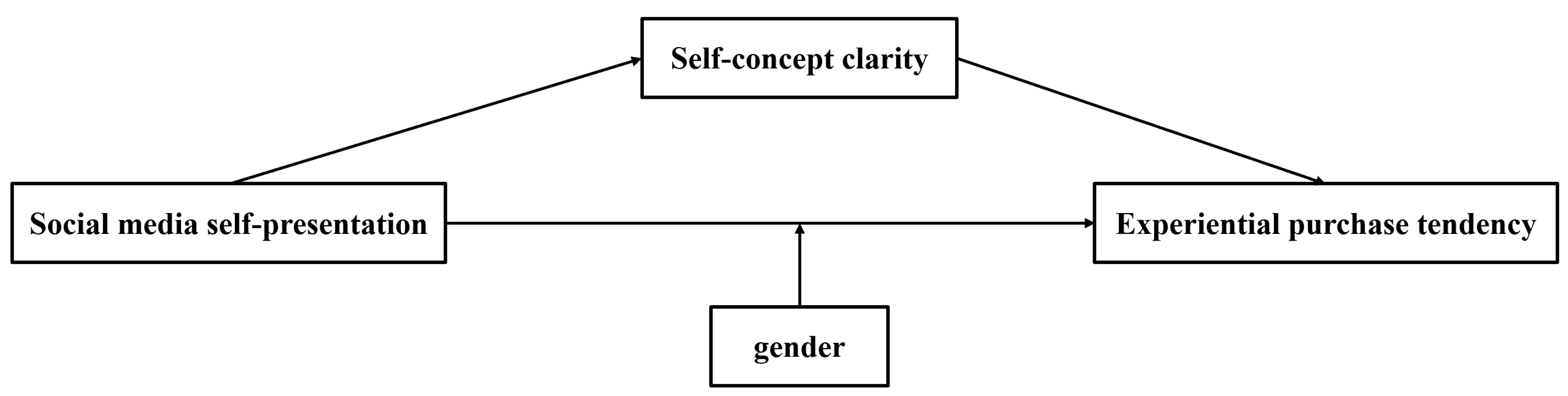

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Media Self-Presentation and Consumers’ Preferences for Experiential Consumption

2.2. The Impact of Social Media Self-Presentation on Consumers’ Preferences for Experiential Consumption

2.3. The Moderating Role of Gender

2.4. The Mediating Role of Self-Concept Clarity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2.2. Results

3.2.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Study 1—Experiential Consumption Preference Scenarios

Appendix A.2. Study 2—Experiential Consumption Preference Scenarios

References

- Chen, H.; Chen, H. Understanding the Relationship between Online Self-Image Expression and Purchase Intention in SNS Games: A Moderated Mediation Investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, H. Investigating the Intention to Purchase Virtual Goods in Social Networking Service Games: A Self-Presentation Perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 41, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—What Is an Interactive Marketing Perspective and What Are Emerging Research Areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Bao, Z.; Li, Y. Why Do Players Purchase in Mobile Social Network Games? An Examination of Customer Engagement and of Uses and Gratifications Theory. Program 2017, 51, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, B. The Presentation of Self in the Age of Social Media: Distinguishing Performances and Exhibitions Online. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2010, 30, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.-E.R. The Facebook Paths to Happiness: Effects of the Number of Facebook Friends and Self-Presentation on Subjective Well-Being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L. Loneliness, Social Support, and Preference for Online Social Interaction: The Mediating Effects of Identity Experimentation Online among Children and Adolescents. Chin. J. Commun. 2011, 4, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zywica, J.; Danowski, J. The Faces of Facebookers: Investigating Social Enhancement and Social Compensation Hypotheses; Predicting FacebookTM and Offline Popularity from Sociability and Self-Esteem, and Mapping the Meanings of Popularity with Semantic Networks. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2008, 14, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Kuo, F. Can Blogging Enhance Subjective Well-Being through Self-Disclosure? Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.L.; Hancock, J.T. Self-Affirmation Underlies Facebook Use. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullwood, C.; Attrill-Smith, A. Up-Dating: Ratings of Perceived Dating Success Are Better Online than Offline. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boven, L.; Gilovich, T. To Do or to Have? That Is the Question. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Liu, L.; Lyu, S.; Wu, L.; Pan, W.T. Who Can Get More Happiness? Effects of Different Self-Construction and Experiential Purchase Tendency on Happiness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 799164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, S.Y.; Feng, K. The Effect of Social Exclusion on Consumer Choice: The Moderating Role of Nostalgia and Mediating Role of Social Connectedness. J. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 45, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar]

- LI, B.; ZHU, Q.; HE, R.; LI, A.; WEI, H. The Effect of Mortality Salience on Consumers’ Preference for Experiential Purchases and Its Mechanism. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2023, 55, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R. Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Swickert, R.J.; Hittner, J.B.; Harris, J.L.; Herring, J.A. Relationships among Internet Use, Personality, and Social Support. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Internet Communication and Its Relation to Well-Being: Identifying Some Underlying Mechanisms. Media Psychol. 2007, 9, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Jin, B.; Jin, S.-A.A. Effects of Self-Disclosure on Relational Intimacy in Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Adolescents’ Identity Experiments on the Internet. Commun. Res. 2008, 35, 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, S. Self-Presentation 2.0: Narcissism and Self-Esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Connecting or Disconnecting: Luxury Branding on Social Media and Affluent Chinese Female Consumers’ Interpretations. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, N.; Eimler, S.C.; Papadakis, A.-M.; Kruck, J.V. Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus? Examining Gender Differences in Self-Presentation on Social Networking Sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, B.R. Self-Presentation: Managing the Impression of Consistency When Reality Interferes with Self-Enhancement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 32, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; van de Ven, N.; Utz, S. What Triggers Envy on Social Network Sites? A Comparison between Shared Experiential and Material Purchases. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, W.; Brucks, M. How and Why Conversational Value Leads to Happiness for Experiential and Material Purchases. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.J.; Gilovich, T. The Relative Relativity of Material and Experiential Purchases. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprariello, P.A.; Reis, H.T. To Do, to Have, or to Share? Valuing Experiences over Material Possessions Depends on the Involvement of Others. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Contemp. Sociol. 1982, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manago, A.M.; Graham, M.B.; Greenfield, P.M.; Salimkhan, G. Self-Presentation and Gender on MySpace. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattel, J.W. The Inexpressive Male: Tragedy or Sexual Politics? Soc. Probl. 1976, 23, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Trapnell, P.D.; Heine, S.J.; Katz, I.M.; Lavallee, L.F.; Lehman, D.R. Self-Concept Clarity: Measurement, Personality Correlates, and Cultural Boundaries. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullwood, C.; James, B.M.; Chen-Wilson, C.-H. Self-Concept Clarity and Online Self-Presentation in Adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullwood, C.; Wesson, C.; Chen-Wilson, J.; Keep, M.; Asbury, T.; Wilsdon, L. If the Mask Fits: Psychological Correlates with Online Self-Presentation Experimentation in Adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J.; Schouten, A.P. Friend Networking Sites and Their Relationship to Adolescents’ Well-Being and Social Self-Esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurchisin, J.; Watchravesringkan, K.; Mccabe, D.B. An Exploration of Identity Re-Creation in the Context of Internet Dating. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2005, 33, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, T.J.; Gilovich, T. I Am What I Do, Not What I Have: The Differential Centrality of Experiential and Material Purchases to the Self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Basic but Frequently Overlooked Issues in Manuscript Submissions: Tips from an Editor’s Perspective. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.T.; Pchelin, P.; Iyer, R. The Preference for Experiences over Possessions: Measurement and Construct Validation of the Experiential Buying Tendency Scale. J. Posit. Psychol. 2012, 7, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Lennox, R.D.; Wolfe, R.N. Revision of the Self-Monitoring Scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Gu, R.; Luo, C. What Type of Purchase Do You Prefer to Share on Social Networking Sites: Experiential or Material? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—The Misassumptions about Contributions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzallah, D.; Leiva, F.M.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. To Buy or Not to Buy, That Is the Question: Understanding the Determinants of the Urge to Buy Impulsively on Instagram Commerce. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Mieiro, S.; Huang, G. How Social Media Advertising Features Influence Consumption and Sharing Intentions: The Mediation of Customer Engagement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Jiang, X.; Fan, X. How Social Media’s Cause-Related Marketing Activity Enhances Consumer Citizenship Behavior: The Mediating Role of Community Identification. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 17, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Lee, C.T.; Lin, W.-Y. Meme marketing on social media: The role of informational cues of brand memes in shaping consumers’ brand relationship. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 588–610. [Google Scholar]

- Samarah, T.; Bayram, P.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Elrehail, H. The Role of Brand Interactivity and Involvement in Driving Social Media Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty: The Mediating Effect of Brand Trust. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial: Demonstrating Contributions through Storytelling. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. The Self; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Dependent Variable | Effect | BootSE | 95%LLCI | 95%ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured by scale | 0.0020 | 0.0012 | 0.0001 | 0.0049 |

| Measured by situational scenarios | 0.0017 | 0.0013 | −0.0002 | 0.0047 |

| Dependent Variable | Effect | BootSE | 95%LLCI | 95%ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive self-presentation | 0.1595 | 0.0754 | 0.0148 | 0.3059 |

| Authentic self-presentation | 0.1709 | 0.0965 | 0.0028 | 0.3646 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. Digital Selves and Curated Choices: How Social Media Self-Presentation Enhances Consumers’ Experiential Consumption Preferences. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030238

Zou Y, Zhang S, Wang Y. Digital Selves and Curated Choices: How Social Media Self-Presentation Enhances Consumers’ Experiential Consumption Preferences. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030238

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Yun, Shengqi Zhang, and Yong Wang. 2025. "Digital Selves and Curated Choices: How Social Media Self-Presentation Enhances Consumers’ Experiential Consumption Preferences" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030238

APA StyleZou, Y., Zhang, S., & Wang, Y. (2025). Digital Selves and Curated Choices: How Social Media Self-Presentation Enhances Consumers’ Experiential Consumption Preferences. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030238