Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Goal-Framing Type and Consumer Decision-Making

2.2. Regulatory Focus Based on Product Type and Its Congruence with Goal-Framing Type

2.3. The Mediating Role of Processing Fluency

2.4. The Impact of Time Pressure on Goal-Framing Type

3. Study 1: The Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making and the Mediating Role of Processing Fluency

3.1. Research Objective

3.2. Research Method

3.2.1. Experimental Design and Participants

3.2.2. Experimental Procedure

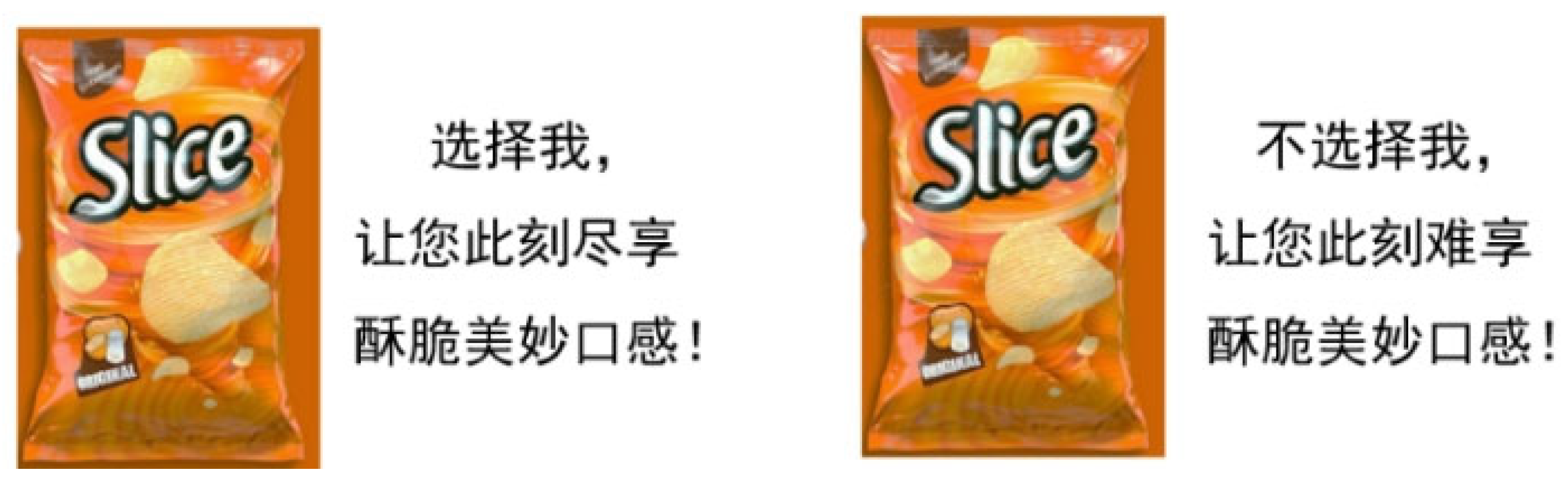

3.2.3. Experimental Materials

3.2.4. Measurement

3.3. Results

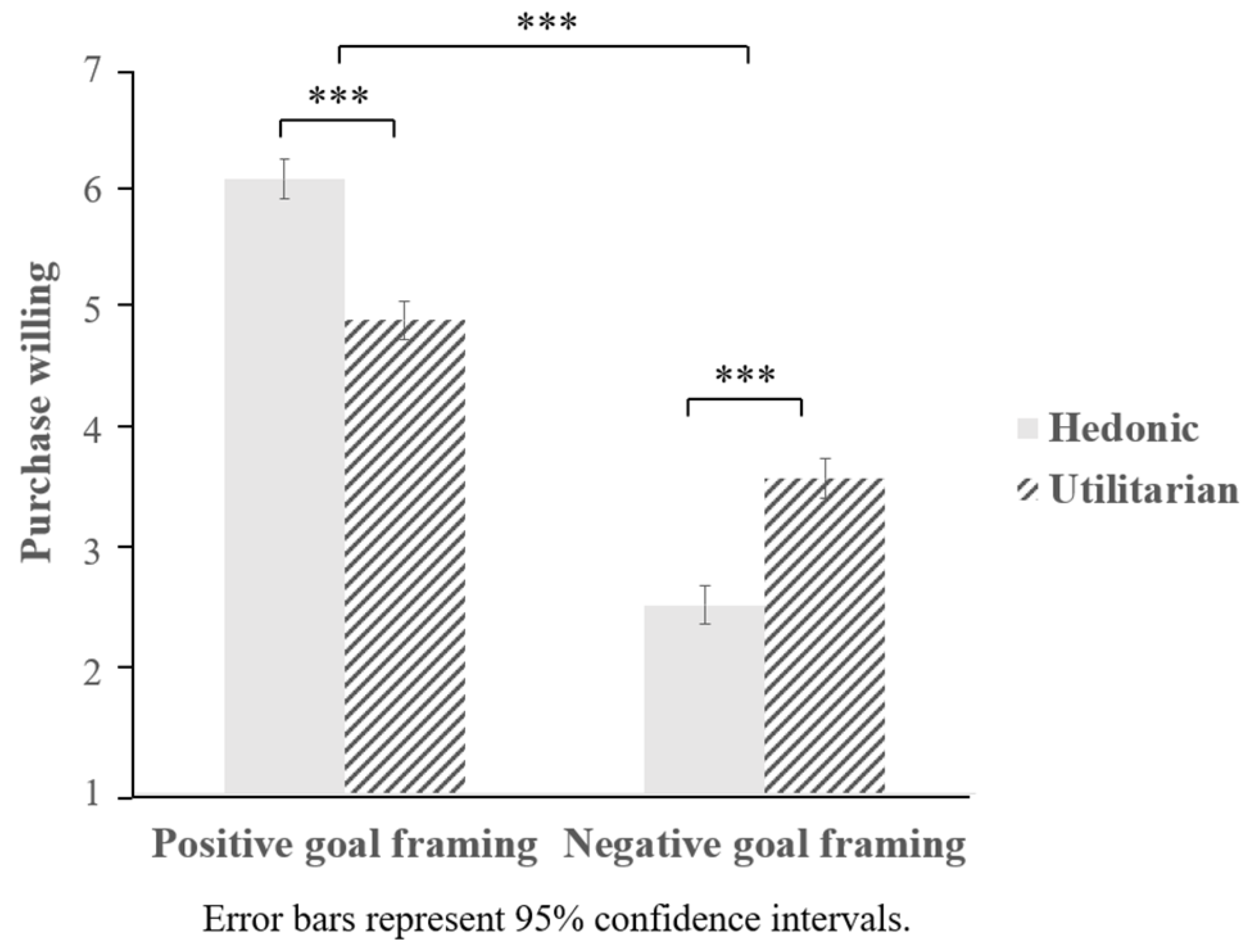

3.3.1. The Influence of Goal Framing and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making

3.3.2. Mediating Role of Processing Fluency

3.4. Discussion

4. Study 2: The Impact of Time Pressure on Goal-Framing Type: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement

4.1. Research Objective

4.2. Research Method

4.2.1. Experimental Design and Participants

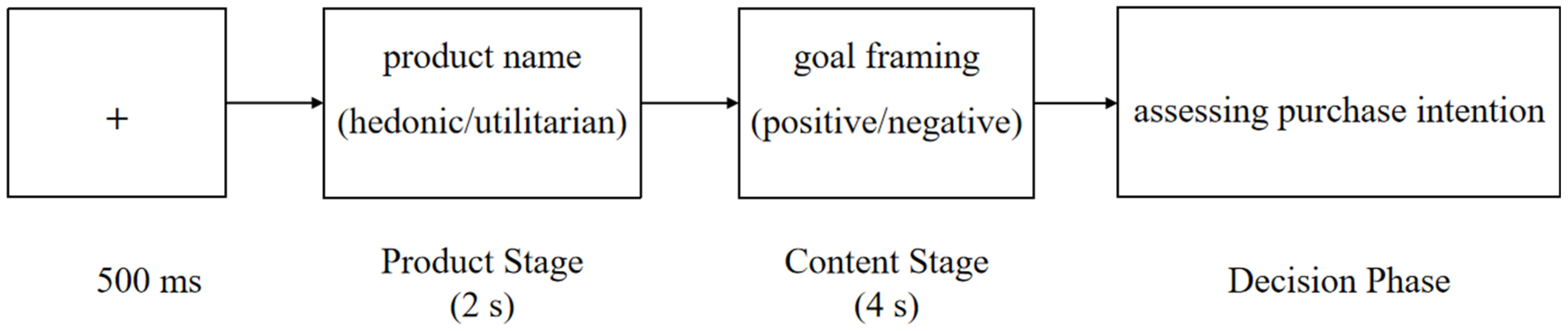

4.2.2. Experimental Procedure

- (1)

- Experimental Preparation Phase

- (2)

- Formal Experimental Phase

4.2.3. Measurement

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Manipulation Check of Time Pressure

4.3.2. The Impact of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making and Advertisement Fixation Under Different Time Pressures

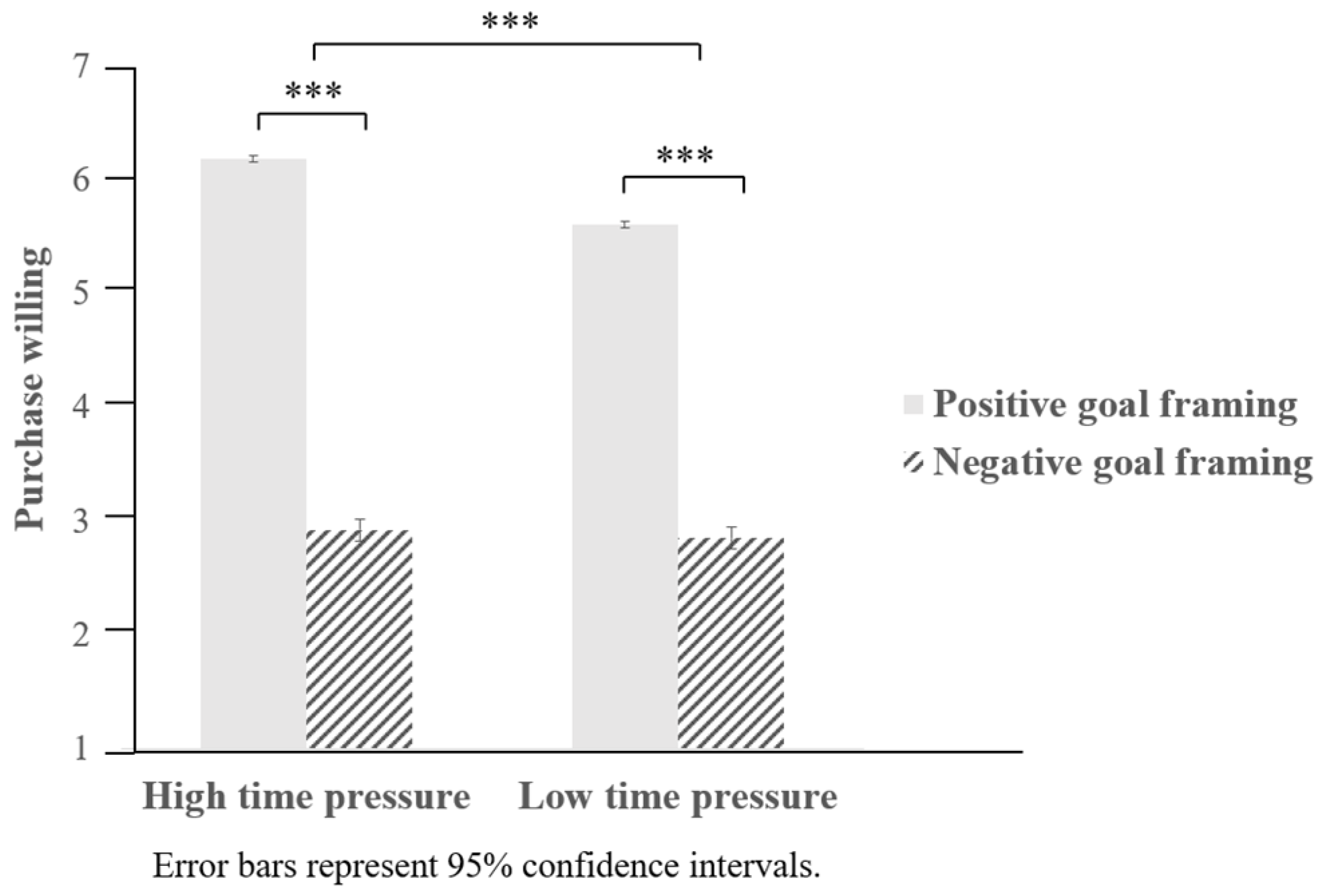

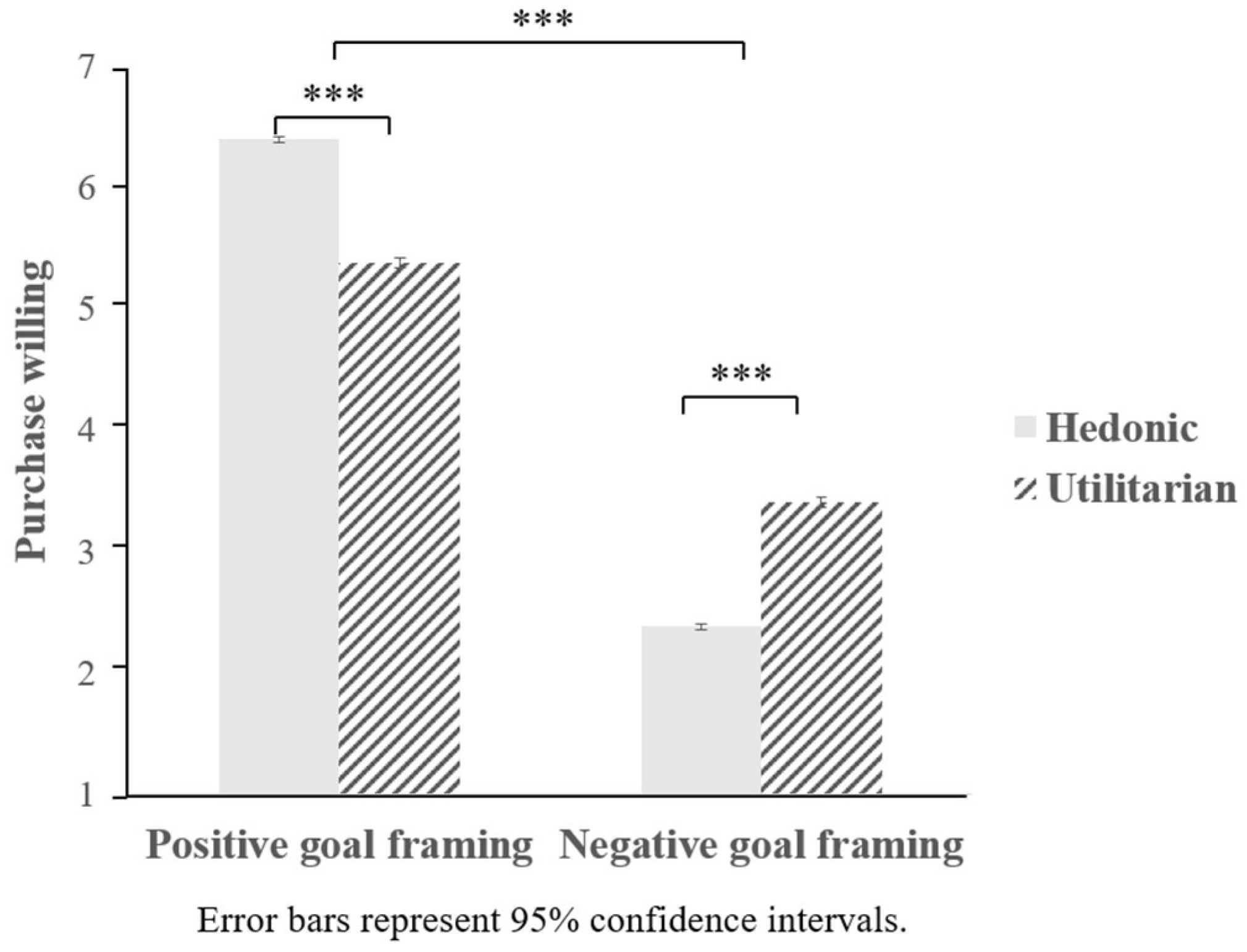

- The Impact of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making under Different Time Pressures

- 2.

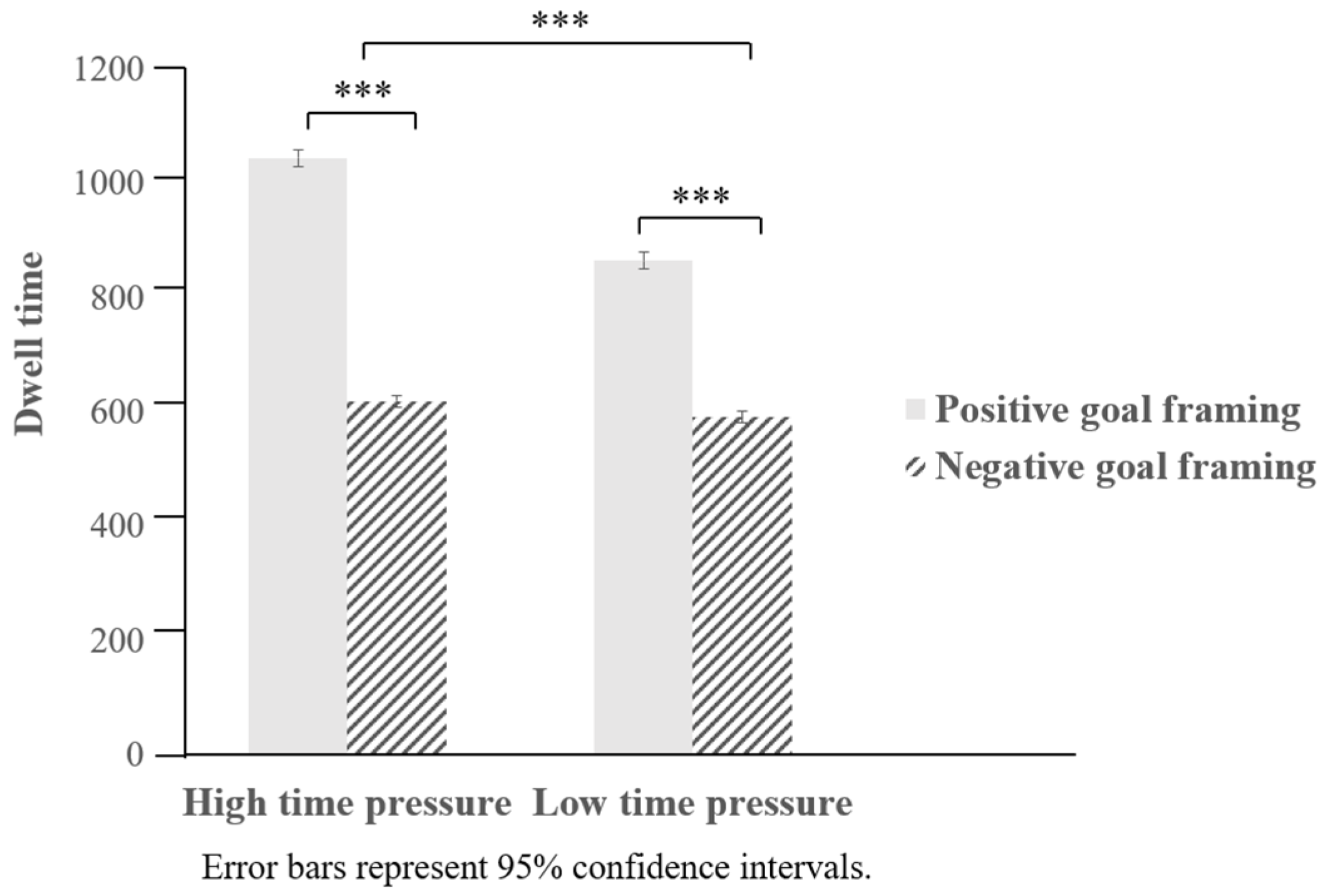

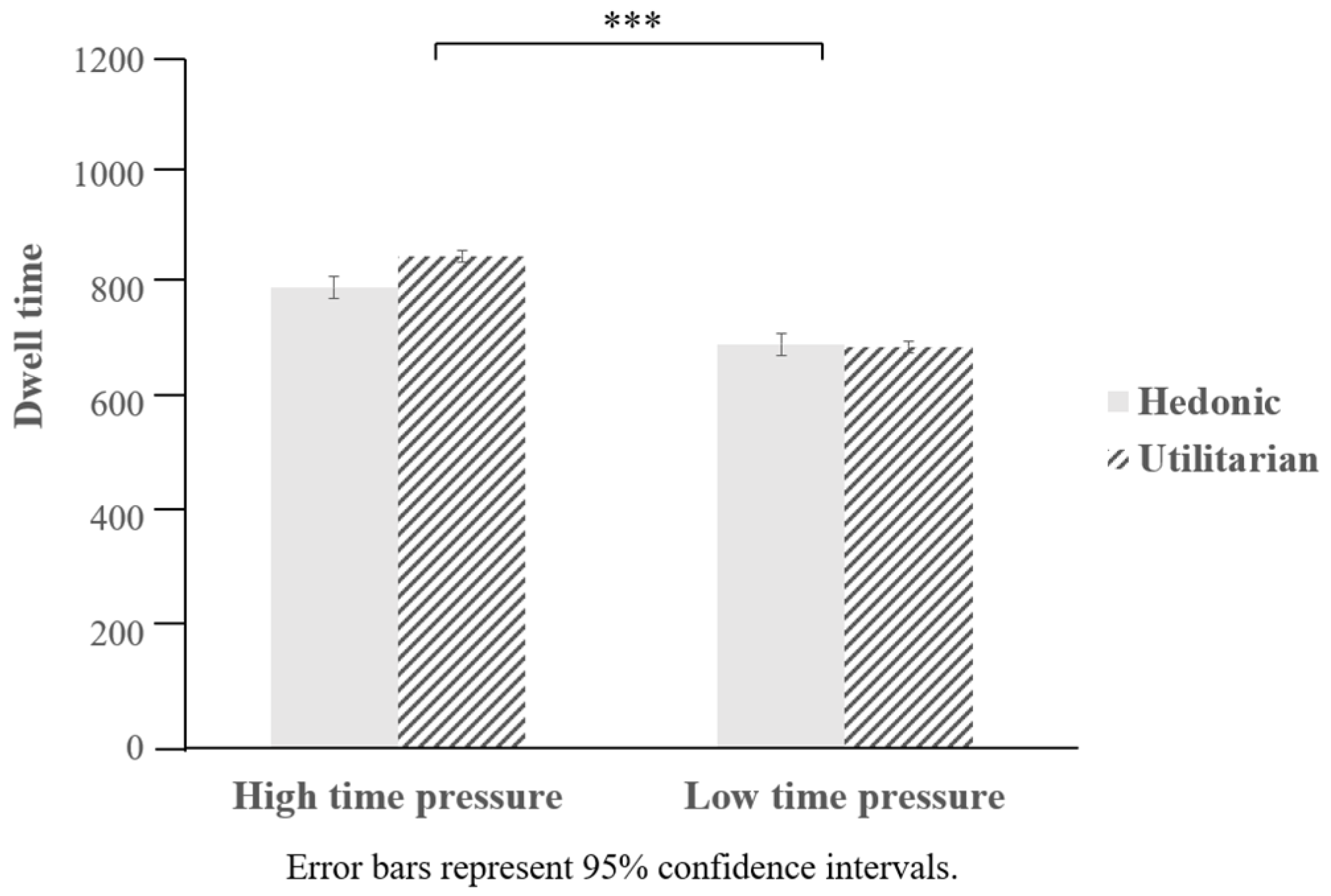

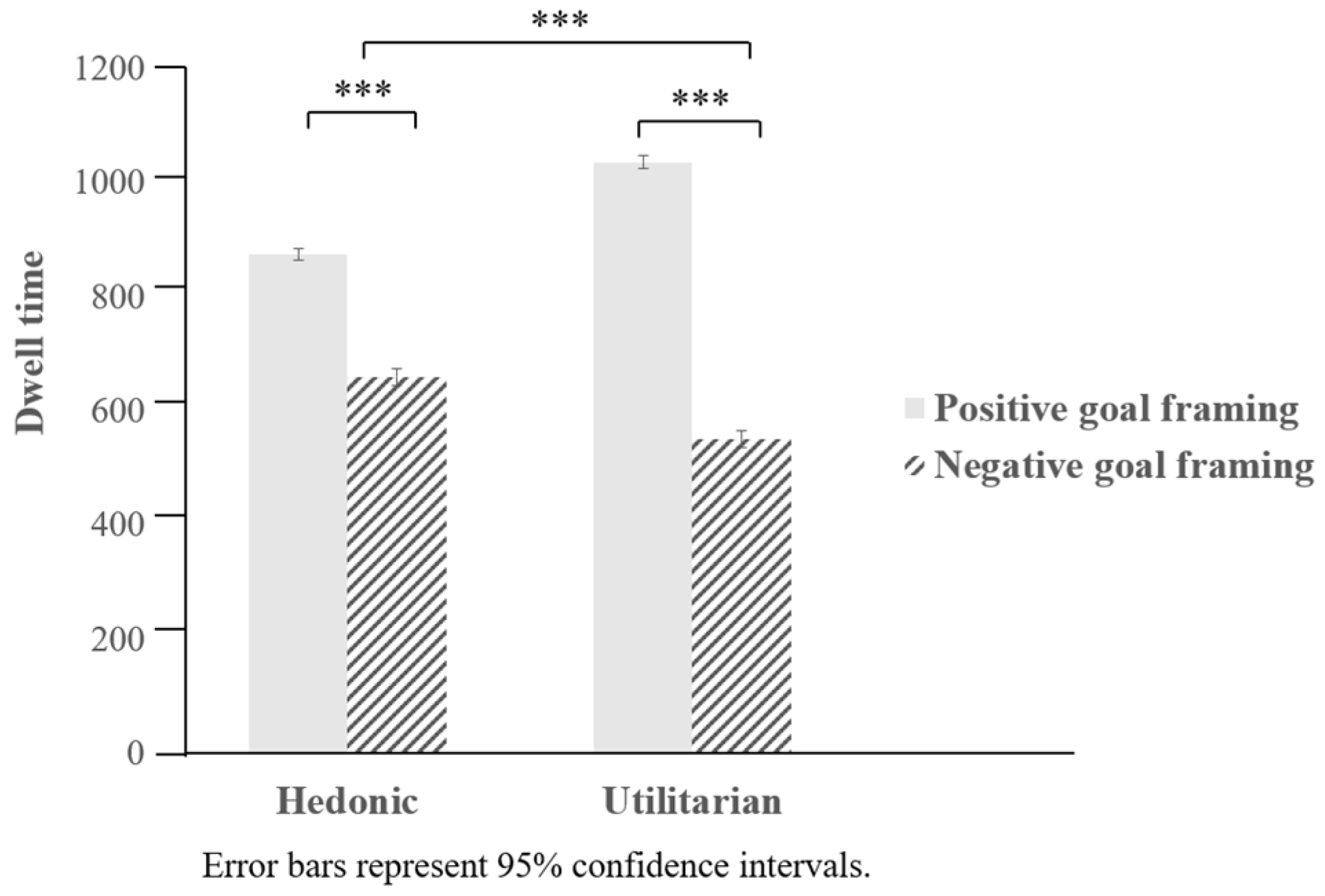

- The Impact of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Ad Fixation under Different Time Pressures

4.4. Discussion

5. General Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Product Attribute Assessment

| Hedonic Goods | Utilitarian Goods | ||||

| Name | Attributes | Attractiveness | Name | Attributes | Attractiveness |

| Toys | 5.78 | 3.67 | Tissue | 2.96 | 4.34 |

| Video game console | 5.96 | 3.70 | Trash can | 2.86 | 3.20 |

| Chocolate | 5.52 | 4 | Body wash | 2.93 | 3.88 |

| Chips | 5.69 | 4.11 | Notebook | 2.93 | 3.10 |

| Bubble tea | 5.62 | 4.58 | Desk lamp | 2.87 | 3.25 |

| Perfume | 5.42 | 3.84 | Umbrella | 2.78 | 3.77 |

| Mystery box | 5.98 | 3.98 | Power bank | 2.78 | 3.96 |

| Designer handbag | 5.94 | 3.31 | Facial cleanser | 2.76 | 3.58 |

| E-cigarette | 6.22 | 2.79 | Hand cream | 2.94 | 3.87 |

| LEGO | 5.43 | 3.64 | Mirror | 2.85 | 3.92 |

| Sunflower seeds | 5.54 | 3.96 | Fan | 2.88 | 3.62 |

| Cocktail | 5.63 | 3.66 | Bedding | 2.79 | 3.44 |

| Scooter | 5.45 | 3.52 | Air conditioner | 2.66 | 4.12 |

| Fresh flowers | 5.42 | 4.08 | Mineral water | 2.95 | 3.36 |

| snacks | 5.44 | 3.90 | Data cable | 2.65 | 3.67 |

| 3D glasses 3D | 5.48 | 3.51 | Water cup | 2.79 | 3.73 |

References

- Wang, L.; Chan, E.Y. Guest Editorial: Brand-Consumer Relationship Management via Interactive Marketing Opportunities. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Paul, J.; Strong, C.; Pius, J. Consumer Response towards Social Media Advertising: Effect of Media Interactivity, Its Conditions and the Underlying Mechanism. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, K. The Effects of Live Comments and Advertisements on Social Media Engagement: Application to Short-Form Online Video. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S. Effects of Mood and Elaboration on Processing and Evaluation Goal-Framed Appeals. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All Frames Are Not Created Equal: A Typology and Critical Analysis of Framing Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, E.; Peer, E. Attribute Framing Affects the Perceived Fairness of Health Care Allocation Principles. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, E.; Waygood, O. Applying Valence Framing to Enhance the Effect of Information on Transport-Related Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Transp. Res. Part A 2013, 48, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerend, M.A.; Sias, T. Message Framing and Color Priming: How Subtle Threat Cues Affect Persuasion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.-H. Use of Message Framing and Color in Vaccine Information to Increase Willingness to Be Vaccinated. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2011, 39, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Tan, P. Applied Research on Framing Effect and Related Techniques. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñon, A.; Gambara, H. A Meta-Analytic Review of Framing Effect: Risky, Attribute and Goal Framing. Psicothema 2005, 17, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach, A.; Finkelstein, S.R. How Feedback Influences Persistence, Disengagement, and Change in Goal Pursuit. In Goal-Directed Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.R.; Fishbach, A. Tell Me What I Did Wrong: Experts Seek and Respond to Negative Feedback. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-F.; Lin, C.-S.; Liu, L.-T. The Effects of Framing Messages and Cause-Related Marketing on Backing Intentions in Reward-Based Crowdfunding. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. The Role of Regulatory Focus in Message Framing in Anti-Smoking Advertisements for Adolescents. J. Advert. 2006, 5, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S. An Examination of Consumer Responses toward Attribute- and Goal-Framed Messages. J. Advert. 2010, 39, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, S.; Zou, Z. Power and Message Framing: An Examination of Consumer Responses toward Goal-Framed Messages. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16766–16775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, G.Y. Effective Destination User-Generated Advertising: Matching Effect between Goal Framing and Self-Esteem. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.H.; Yue, B.B.; Gong, S.Y. Impact of the Matching Effect between Green Advertising Appeal and Information Framework on Consumer Responses. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 16, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, W.; Brüggen, E.; Post, T.; Hoet, C. Engagement Behavior and Financial Well-Being: The Effect of Message Framing in Online Pension Communication. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ma, B. Optimizing Positive Goal Framing in Advertising: Differential Consumer Responses to New Product Categories. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetto, L.M.; Stein, L.M. Moderating Effects of Consumer Involvement and the Need for Cognition on Goal Framing. Interam. J. Psychol. 2010, 44, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Volkova, A.; Cho, H. Warm for Fun, Cool for Work: The Effect of Color Temperature on Users’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Mobile Apps. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods and Propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to Charity as Purchase Incentives: How Well They Work May Depend on What You Are Trying to Sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Ng, S. Regulatory Focus and Preference Reversal between Hedonic and Utilitarian Consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiene, S.M.; Barta, W.D.; Zelenski, J.M.; Deelisa, C. Why Are You Bringing up Condoms Now? The Effect of Message Content on Framing Effects of Condom Use Messages. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, P.; Voss, J.; Ryan, C.; Michael, M.C.; John, D.J. Influencing Health Decision-Making: A Study of Colour and Message Framing. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkielman, P.; Cacioppo, J.T. Mind at Ease Puts a Smile on the Face: Psychophysiological Evidence That Processing Facilitation Elicits Positive Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, D.M. The Secret Life of Fluency. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenkov, G.Y.; Haws, K.L.; Jung, M. Fluency in Future Focus: Optimizing Outcome Elaboration Strategies for Effective Self-Control. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2014, 5, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Adaval, R. Contrast and Assimilation Effects of Processing Fluency. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.Y.; Fu, J.H.; Li, D.M. The Influence of Thematic Product Displays on Consumers: An Elaboration-Based Account. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Jin, J.; Liu, R. The matching effect of influencer style and product type on purchase: The mediating role of processing fluency. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, X. Chatbot or human? The impact of online customer service on consumers’ purchase intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2186–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Aaker, J.L. Bringing the Frame into Focus: The Influence of Regulatory Fit on Processing Fluency and Persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Cesario, J.; Molden, D.C.; Kosloff, S.; Higgins, E.T. Incidental Experiences of Regulatory Fit and the Processing of Persuasive Appeals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 1342–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenson, O.; Maule, A.J. Time Pressure and Stress in Human Judgment and Decision Making; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfey, A.G.; Chang, L.J. Multiple Systems in Decision Making. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1128, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Kocher, J.; Julius, P.; Stefan, T.T. Tempus Fugit: Time Pressure in Risky Decisions. Manag. Sci. 2011, 59, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Huang, L. The Persuasive Effects of Scarcity Messages on Impulsive Buying in Live-Streaming E-commerce: The Moderating Role of Time Scarcity. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 37, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, A.; Trueblood, J.S. A Dynamic Dual Process Model of Risky Decision Making. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 270–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, A.; Wyszynski, M.; Traub, S. Need, Frames, and Time Constraints in Risky Decision-Making. Theory Decis. 2020, 89, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Xiao, M.S.; Han, L. The Influence of Materialism and Time Pressure on Risky Decision-Making. J. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 42, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.D.; Teoh, Y.Y.; Cendri, A.H. Time to Pay Attention? Information Search Explains Amplified Framing Effects under Time Pressure. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 33, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Trueblood, J.S.; Diederich, A. Thinking Fast Increases Framing Effects in Risky Decision Making. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Kao, D.T.; Chuang, S.-C.; Wu, P.-H. The Persuasiveness of Framed Commercial Messages: A Note on Marketing Implications for the Airline Industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2006, 12, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Sarial-Abi, G.; Gürhan-Canli, Z. Effect of Regulatory Focus on Selective Information Processing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.L.; Nambiar, D.; Suman, G. Using Eye-Movements to Assess Underlying Factors in Online Purchasing Behaviors. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1365–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.; Rick, S.; Wimmer, G.E.; Prelec, D.; Loewenstein, G. Neural Predictors of Purchases. Neuron 2007, 53, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, T.A.; Camerer, C.F.; Rangel, A. Self-Control in Decision-Making Involves Modulation of the vmPFC Valuation System. Science 2009, 324, 646–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabet, G.; Christian, E.E.; Neuner, M.; Weber, B.A. Neurological Study of Compulsive Buying Behaviour. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, Y.N.; Ou, L. The Typeface Curvature Effect: The Role of Typeface Curvature in Increasing Preference toward Hedonic Products. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1118–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Z.; Fan, X.W.; Ou, Y.J.Y. Consumer Self-Construal, Need of Uniqueness and Preference of Brand Logo Shape. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.P.; Zhao, H.F.; Xiong, J.P.; Zhou, Z.K. The Relationship between Facial Emotion Expression and Online Charity Donation: A Mediated Moderation Model. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2020, 18, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.; Chen, K.; Jin, R. The Effect of Message Framing and Language Intensity on Green Consumption Behavior Willingness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 2432–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura, K.M.; Mayer, S.; Landwehr, J.R. Measuring Processing Fluency: One versus Five Items. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weenig, M.W.H.; Maarleveld, M. The Impact of Time Constraint on Information Search Strategies in Complex Choice Tasks. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S.; Ratchford, B.T. A Model of Search Behavior with an Application to Grocery Shopping. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, J.; Nugroho, L.; Santosa, P.; Ferdiana, R. The Measurement of Consumer Interest and Prediction of Product Selection in E-Commerce Using Eye Tracking Method. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2018, 11, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xue, F.; Barton, M.H. Visual Attention, Brand Personality and Mental Imagery: An Eye-Tracking Study of Virtual Reality (VR) Advertising Design. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Bao, A.; Lv, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Chi, Y.; Zuo, J. The influence of message frame and product type on green consumer purchase decisions: An ERPs study. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 23232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Saito, T.; Onuma, T. Eye-Tracking Research on Sensory and Consumer Science: A Review, Pitfalls and Future Directions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Fung, N.L.K.; Chu, L.; Wang, D.; Fung, H.H. Framing Effects on Attention to Advertisements and Purchase Intentions among Younger and Older Adults. Cogn. Emot. 2025, 39, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Jasko, K.; Winkielman, P. Fluency, Prediction and Motivation: How Processing Dynamics, Expectations and Epistemic Goals Shape Aesthetic Judgements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20230326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Han, B.; Liu, P. Sustaining Attention to Positive while Early Vigilance for Negative Environmental Information: Evidence from Eye Movements. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 106, 102717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Hao, A.; Deng, J. How Social Presence Influences Consumer Purchase Intention in Live Video Commerce: The Mediating Role of Immersive Experience and the Moderating Role of Positive Emotions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, J.W.; Dahl, A.J.; Drury, L.; Khan, T. Cutting-Edge Research in Social Media and Interactive Marketing: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 900–944. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial–What Is an Interactive Marketing Perspective and What Are Emerging Research Areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Basic but Frequently Overlooked Issues in Manuscript Submissions: Tips From An Editor’s Perspective. J. Appl. Bus. Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achar, C.; So, J.; Agrawal, N.; Duhachek, A. What We Feel and Why We Buy: The Influence of Emotions on Consumer Decision-Making. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.X.; Zeng, K.J.; Chan, H.; Yu, I.Y. Managing Loyalty Program Communications in the Digital Era: Does Culture Matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial: Demonstrating Contributions Through Storytelling. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Goal-Framing Type | Product Type | Purchase Willing (M ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Positive type | hedonic product | 6.06 ± 0.56 |

| utilitarian product | 4.92 ± 0.64 | |

| Negative type | hedonic product | 2.56 ± 0.78 |

| utilitarian product | 3.61 ± 0.72 |

| Time Pressure | Framing Type | Product Type | Purchase Willing (M ± SD) | Dwell Time (M ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Positive | Hedonic | 6.70 ± 0.16 | 944.57 ± 208.50 |

| Utilitarian | 5.66 ± 0.28 | 1144.70 ± 55.38 | ||

| Negative | Hedonic | 2.37 ± 0.66 | 663.35 ± 69.69 | |

| Utilitarian | 3.46 ± 0.89 | 573.50 ± 87.82 | ||

| Low | Positive | Hedonic | 6.10 ± 0.19 | 803.24 ± 65.06 |

| Utilitarian | 5.10 ± 0.25 | 926.04 ± 46.02 | ||

| Negative | Hedonic | 2.36 ± 0.62 | 655.85 ± 84.11 | |

| Utilitarian | 3.33 ± 0.79 | 526.37 ± 57.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, T.; Deng, S. Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030237

Wei S, Gao J, Zhao T, Deng S. Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030237

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Siyuan, Jing Gao, Taiyang Zhao, and Shengliang Deng. 2025. "Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030237

APA StyleWei, S., Gao, J., Zhao, T., & Deng, S. (2025). Influence of Goal-Framing Type and Product Type on Consumer Decision-Making: Dual Evidence from Behavior and Eye Movement. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030237