1. Introduction

To thrive in today’s fiercely competitive digital marketplace, brands strategically utilize social media marketing activities (SMMA) to cultivate and maintain enduring customer relationships. SMMA comprises activities such as customization, interaction, word of mouth (WOM), trendiness, and entertainment aimed at leveraging social media platforms to enhance brand visibility and customer engagement (CE) [

1,

2]. Given its significance, prior research examined the key marketing outcomes of SMMA, demonstrating its positive effects on brand loyalty, customer satisfaction, customer equity, premium pricing, and purchase intentions [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, despite the growing reliance on social media in service industries, several critical and underexplored gaps remain—most notably, the limited understanding of how SMMA drives CE and relational benefits in the banking sector [

1,

8,

11,

12].

While researchers acknowledge that SMMA influences CE [

4,

8], empirical evidence remains limited. Although previous research investigated community engagement [

3] and user engagement [

11], these perspectives overlook the complete conceptualization of CE, which includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects [

13]. This gap is particularly critical in banking, where brand trust and long-term relationships are essential. Although CE is widely regarded as a positive phenomenon, its impact within banking received limited scholarly attention [

14]. Banking services are sensitive due to financial aspects and strict regulations, making customer–brand interactions on social media more complex than in other industries. A well-managed SMMA strategy can strengthen customer trust and engagement, but if mismanaged, it may lead to customer dissatisfaction or disengagement [

15].

In addition, the exploration of the influence of SMMA on relational benefits received limited scholarly attention, particularly within the banking sector. As banks increasingly rely on digital platforms to maintain customer relationships, understanding how SMMA enhances specific relational benefits—namely, confidence benefits, special treatment benefits, and social benefits—is both timely and essential. These relational benefits are especially critical in trust-based industries such as banking, where customer retention and loyalty hinge on perceived relationship value. By empirically validating the influence of SMMA on these relational dimensions, the present study addresses a key research gap and responds to ongoing scholarly calls for deeper investigation into social media’s role in service-based relationship building [

16].

Furthermore, the objective of most marketing efforts is to achieve positive branding outcomes [

17,

18]. The research on SMMA is no different, with more attention given to branding outcomes such as brand equity and loyalty [

1,

5,

9,

10]. However, a growing shift away from profit-centric models highlights the need for a more relationship-driven approach [

19]. This is particularly important in banking services, which are intangible and require continuous CE [

20]. Thus, relationship equity—a bond between customers and brands based on special relationship elements [

21]—is considered more critical than traditional branding outcomes [

22]. Even though relationship equity is recognized as a key marketing outcome, its antecedents—specifically relational benefits and CE—remain underexplored [

23]. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how SMMA drives both relational benefits and CE, ultimately contributing to relationship equity in the banking sector.

Furthermore, existing literature demonstrates that CE fosters favorable relational outcomes [

21,

24], there is insufficient evidence regarding its direct effects on relationship equity. Previous research explored how engagement via mobile apps impacts customer equity [

25,

26]. However, these more general perspectives ignore how CE specifically translates into deeper, long-term brand relationships. In the digital era, CE has become essential for building long-term relationships, as consumers want interactive and personalized experiences in banking [

27]. Although banks recognize the value of strong customer relationships, how customers perceive relational benefits in social media banking remains unclear. This study fills a notable gap by simultaneously examining CE and relational benefits as joint antecedents of relationship equity in the banking sector—a context where such connections are particularly underexplored.

To explain these relationships more systematically, this study draws on social exchange theory (SET), which provides a foundational framework for explaining how brands and consumers engage in mutually beneficial interactions via SMMA. Rooted in the principle of reciprocity, SET posits that individuals participate in exchanges when they perceive that potential rewards outweigh costs [

28]. In the banking sector, SMMA acts as an initial value offering, where banks engage customers through customized content, interactive communication, and relationship-building activities. In response, customers reciprocate through engagement, trust, and loyalty, ultimately strengthening relationship equity. While SET has been widely applied in relationship marketing [

29,

30], its specific application to understanding how SMMA influences CE and relational benefits in banking remains limited [

6]. By leveraging SET, this study provides a novel perspective on how SMMA fosters long-term consumer–brand relationships.

The research of SMMA predominantly relied on cross-sectional designs [

3,

4,

7,

9]. However, cross-sectional studies have inherent limitations, particularly in their inability to establish causal relationships due to common method bias and reverse causality concerns [

31]. In contrast, experimental designs offer greater internal validity [

17], allowing researchers to test how SMMA influences its outcomes while controlling for extraneous variables. Prior studies have explicitly called for experimental approaches to overcome these limitations and gain a more rigorous understanding of SMMA’s consequences [

3,

4,

7]. This study addresses these methodological shortcomings by adopting a between-subject experimental design, thus contributing to both theoretical rigor and practical relevance. Using real social media ads enhances ecological validity while controlling for confounding factors. This approach strengthens evidence on the causal effects of SMMA, offering valuable theoretical and practical insights into digital marketing.

To summarize, this study identified several critical research gaps and contributes meaningfully by addressing them through multiple objectives. First, it empirically validates the relationship between SMMA and CE, a multidimensional construct essential in trust-intensive industries, such as banking, yet understudied in existing literature. Second, the role of SMMA in shaping relational benefits—and ultimately relationship equity—remains unexplored in the digital service context, despite the recognized importance of relational benefits in fostering long-term customer equity. This study addresses this gap and offers valuable insights for both academics and practitioners. Third, it investigates how CE and relational benefits act as joint drivers of relationship equity, thereby deepening the understanding of how customer–brand bonds are formed in digital environments. Finally, this study addresses a key methodological gap by employing a between-subjects experimental design—overcoming limitations of prior cross-sectional research and enhancing causal inference. By using real social media ads, the study also strengthens ecological validity, ensuring that the findings offer both theoretical rigor and practical relevance.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

While various theories could be employed to explain the dynamics of social media marketing and customer–brand relationships, SET provides a particularly suitable framework for this study [

32]. It suggests that people form relationships when the perceived rewards outweigh the costs. In marketing, SET has been extensively used to explain customer–brand interactions, particularly in relationship marketing and CE [

29,

30,

33]. On the other hand, the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model emphasizes how external stimuli (e.g., marketing messages) influence internal states (organism) and ultimately lead to behavioral responses [

34]. Although relevant, SOR does not sufficiently capture the ongoing, reciprocal nature of consumer–brand relationships. Similarly, the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) focuses on how consumers process persuasive messages via central or peripheral routes [

35], yet it overlooks the emotional and relational exchanges central to long-term CE. Relationship marketing theory, while focused on fostering customer loyalty through relational bonds [

36], lacks the micro-level explanation of how perceived benefits and costs drive customer behavior.

In contrast, SET offers a robust and flexible framework to explain how customers engage with brands on social media platforms through a series of reciprocal exchanges. By focusing on perceived value, trust, and mutual reward, SET aligns more closely with the constructs of this study, including CE and relational benefits. It is thus better suited for exploring the mechanisms underlying relationship equity in the banking sector. Building on SET, this study conceptualizes brand–customer interaction in three key stages: (a) initial value offering, where brands use SMMA to initiate engagement through informative, personalized, and interactive content; (b) exchange participation and reward, where customers respond by engaging with the brand and receive relational benefits (social, special treatment, and confidence) in return; and (c) the net value of the relationship, where continued exchanges result in long-term customer commitment and relationship equity. This framework aligns with prior calls for a stronger theoretical foundation in SMMA research [

6]. It extends SET by demonstrating how social media marketing serves as a mechanism for fostering sustained consumer–brand relationships. By integrating SET into the SMMA context, this study presents a novel theoretical framework for understanding the dynamics of relationship marketing driven by social media and provides practical insights for service brands looking to increase customer loyalty.

SMMA and customer engagement

SMMA refers to the set of activities that are designed to engage customers through social media platforms, which comprises five key dimensions—entertainment, interaction, trendiness, WOM, and customization [

1,

2]. Each of these dimensions contributes uniquely to CE in digital spaces.

Entertainment refers to the extent to which a brand’s social media content is enjoyable and engaging, which includes the use of humor, storytelling, visually appealing formats, gamification, or interactive features [

2]. Several research studies indicate that users tend to elicit higher engagement with entertaining content by brands [

2,

9,

12].

Interaction reflects a brand’s capacity to initiate and sustain two-way communication with users across social media platforms. This involves practices such as responding to consumer comments, facilitating discussions, conducting live sessions, and encouraging user-generated content. These interactions play a vital role in building customer trust and stimulating CE with a brand [

37].

Trendiness is a brand’s ability to stay relevant and up-to-date in its social media content. This dimension of SMMA reflects how well a brand presents content on its social media platforms in alignment with the target audience’s interests and current trends in the digital landscape [

1].

WOM refers to the voluntary sharing of brand-related experiences by consumers through social media channels. WOM can be in the form of reviews, testimonials, brand experiences, or informal recommendations [

4]. Consumers consider WOM content as more credible and trustworthy than firm-generated content [

9,

31,

38].

Finally, customization refers to the degree to which social media content is tailored to align with the specific preferences, behaviors, and interests of individual consumers. Through data-driven personalization, brands can deliver more relevant and targeted messages, thereby increasing the effectiveness of marketing communications and perceived brand value [

4,

37].

Existing research supports the idea that SMMA positively influences CE, which is defined as the level of a customer’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral investment in specific brand interactions [

13,

39]. In trust-driven service industries, such as banking, continuous CE is essential for developing strong and lasting brand relationships [

14,

30]. For instance, studies demonstrated that user engagement and connection with the brand are enhanced through customization, interaction, WOM, trendiness, and entertainment [

3,

11]. Likewise, Zeqiri, Koku, Dobre, Milovan, Hasani, and Paientko [

10] found that SMMA positively influences customer brand engagement on social media.

The relationship between SMMA and CE can be explained through the lens of SET, in which brands initiate an exchange relationship by offering value through their content and interactions. Each dimension of SMMA reflects a distinct form of value: entertainment provides emotional rewards through engaging and enjoyable content; interaction reduces psychological distance by fostering two-way communication; trendiness signals brand relevance, enhancing perceived social value; WOM adds credibility by leveraging peer influence; and customization delivers personalized content that aligns with individual needs, increasing perceived utility [

14,

20,

25]. According to SET, when consumers perceive these brand-initiated efforts as rewarding, they are more likely to reciprocate through behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement with the brand. Therefore, CE can be viewed as a return on the social value offered through SMMA. In this exchange framework, CE reflects the consumer’s reciprocation for the brand’s value-laden SMMA efforts. This exchange is particularly relevant in services such as banking, where trust, personalization, and relationship-building are central to customer experience. From here on, all proposed hypotheses on service literature will pertain to the banking context. Specifically,

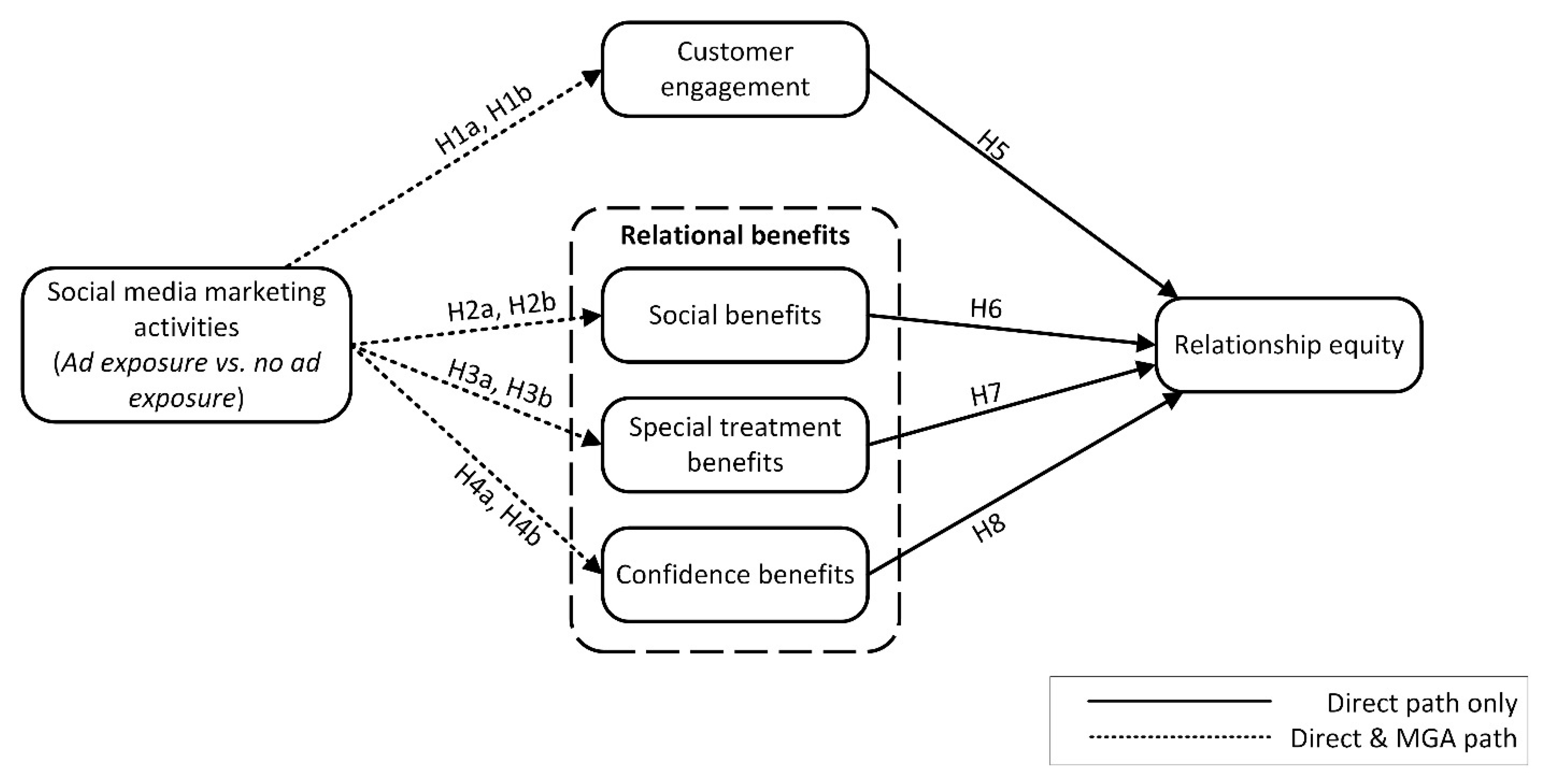

H1a. Banks’ SMMA positively influences CE.

Social media ads are potent tools for effectively grabbing consumer attention and conveying messages due to their rich multimedia content, combining text, images, and videos [

40]. Research indicates that these ads significantly impact consumer choices by creating deep emotional and cognitive connections through rich, engaging content [

18]. Moreover, social media ads are interactive, encouraging active consumer participation through features such as likes, shares, and comments, boosting engagement [

41]. Additionally, the literature suggests that social media ads have differential effects on consumer attitudes and behaviors depending on the experimental treatment. For instance, studying diversity and inclusion in social media advertising, Qayyum, Jamil, Shah, and Lee [

18] demonstrated that engagement was escalated when consumers were exposed to inclusive ads rather than non-inclusive ads. Likewise, Abell and Biswas [

40] noted differences in engagement levels when consumers viewed healthy versus unhealthy food ads on Facebook. In a similar effort, by comparing groups exposed to social media ads (vs. without ads), we can better understand how the effect of SMMA on CE is amplified.

H1b. Consumers exposed to a bank’s social media advertisement exhibit higher CE than those who are not exposed.

2.1. SMMA and Relational Benefits

Relational benefits are additional advantages (apart from core service) that customers reap from long-term relationships with service providers [

42]. Owing to the increased interest of marketers and researchers in relationship marketing [

30,

43], the importance of relational benefits amplified in services. It is increasingly recognized that business success is driven not only by profitability, but also by the strength of customer relationships and the care extended to them [

25]. Moreover, recent studies confirmed that nurturing relationships boosts customer satisfaction, value, and loyalty with service brands [

22,

24]. Receiving more attention, Gwinner, et al. [

44] identified, which was further explored by Gremler, Van Vaerenbergh, Brüggen, and Gwinner [

33], that the relational benefits fall into three categories: social, special treatment, and confidence benefits.

Social benefits refer to establishing a close bond with the service firm, including familiarity, friendship, and personal recognition from the staff [

29,

44]. Existing research primarily examined the outcomes of relational benefits, but the factors that foster these benefits have been largely overlooked, particularly in the context of SMMA. Among the noticeable efforts is the study by Zollo, et al. [

45], which showed the significant influence of SMMA on social benefits for service brands.

Drawing on SET, this study conceptualizes social benefits as reciprocal outcomes of perceived value exchanges between the brand and the consumer. In this context, SMMA represents the brand’s proactive effort to offer social and emotional value—through personalized content, community engagement, recognition, and conversational interactions. These actions reduce social distance and foster a sense of inclusion and belonging. In return, consumers reciprocate by forming social bonds and perceiving stronger social benefits. Thus, SET uniquely explains this pathway by framing SMMA as an initial value offering and social benefits as a relational reward, reinforcing the ongoing exchange between brand and consumer. Aligned with this, Ibrahim and Aljarah [

4] argued that SMMA is positively related to enhanced perception of relationship quality in the service industry. Furthermore, SMMA cultivates an emotional bond between the customer and the brand. Therefore, we propose the following:

H2a. Banks’ SMMA positively influences social benefits.

Social media ads are particularly effective in cultivating social benefits by establishing emotional connections [

18,

40]. Recent research indicates that exposure to social media ads enhances consumer participation [

18] and a sense of personal bond with the service brand [

4], fostering their relational benefits. As noted earlier, exposure to social media advertising leads to amplified effects on consumer outcomes [

18,

40]; we expect a stronger effect of SMMA on social benefits when consumers view social media ads. Therefore,

H2b. Consumers exposed to a bank’s social media advertisement perceive higher social benefits than those who are not exposed.

Special treatment benefits (STBs) encompass customization and economic elements, including preferential treatment, extra attention, price discounts, and faster service [

33,

44]. Customers who have established relationships with a service provider often receive better deals, quicker service, and more personalized offerings than those without such a relationship [

33,

43]. According to SET [

28], such benefits are perceived as relational rewards exchanged for prior engagement. SMMA acts as a value offering—through personalized content, exclusive deals, and direct interaction—that encourages customers to reciprocate with continued participation. STB, including preferential treatment, personalized attention, discounts, and expedited service, is thus viewed as an outcome of this reciprocal exchange [

43,

46]. Research indicates that active social media participants often receive superior offers and tailored service experiences [

45,

47], supporting the SET-driven exchange mechanism. By fostering reciprocity and trust, SMMA enhances customer satisfaction and strengthens brand relationships.

H3a. Banks’ SMMA positively influences STB.

STBs are exclusive rewards and tailored services for customers who engage with the brand [

29], and this is more pronounced in social media [

33]. Social media ads are crucial in showcasing these benefits by featuring exclusive offers, personalized content, and tailored experiences for the target audience [

48]. Since consumers often visit social media for information about services [

45,

49], the ads portraying exclusive promotions and customized content foster a sense of exclusivity and special treatment. Consumers prefer social media ads that resonate with their preferences [

17], beliefs [

18], and expectations [

48].

H3b. Consumers exposed to a bank’s social media advertisement perceive higher STB than those who are not exposed.

Confidence benefits refer to the sense of reduced anxiety and perceived risk, as well as escalated trust in the service provider [

44]. Recent studies argue that confidence benefits are built on the foundations of trust [

46,

47]. From the perspective of SET [

37], SMMA acts as a relational value offering—through consistent, transparent, and supportive interactions—that reduces uncertainty and encourages reciprocal trust from consumers. For instance, Ibrahim and Aljarah [

4] found that SMMA enhances relationship quality, including trust with service providers. In turn, such engagement lowers perceived purchase risks and strengthens consumer confidence, as customers gain a clearer understanding of service expectations through repeated positive interactions. This is consistent with the findings of Khan, Hollebeek, Fatma, Islam, Rather, Shahid, and Sigurdsson [

30], who elaborated that social media promotional and engagement activities conducted by service brands lead to greater trust and relationship quality. Thus, in SET terms, confidence benefits represent a relational reward for the consumer’s trust and participation in the brand’s social media exchange.

H4a. Banks’ SMMA positively influences confidence benefits.

Confidence benefits pertain to consumers’ interaction with a brand on social media, developing a sense of reliability and reducing uncertainty [

33]. Social media ads that promote safe products [

17,

40] and consumer testimonials [

18] are likely to enhance confidence benefits. Similarly, consistently delivering on the level of service promised in advertising can strengthen confidence benefits [

33]. Therefore, it is expected that the effect of SMMA on confidence benefits will be enhanced when consumers are exposed to social media ads (compared to no exposure).

H4b. Consumers exposed to a bank’s social media advertisement perceive higher confidence benefits than those who are not exposed.

2.2. Drivers of Relationship Equity

Relationship equity pertains to the bond between customers and brands established through unique relationship elements [

26]. Existing research highlighted its positive outcomes, such as consumer trust [

21], advocacy behavior [

24], and repurchase intentions [

50]. In contrast, research remained silent regarding the drivers of stronger and lasting customer relationships with service brands [

23,

51].

Grounded in SET [

28], this study conceptualizes CE as the consumer’s investment in the relationship—a behavioral, emotional, and cognitive response to the brand’s value-laden efforts [

28]. According to Sallaku and Vigolo [

52], SET is particularly relevant for understanding how engagement-driven interactions translate into long-term relational outcomes. When customers perceive CE experiences as beneficial (e.g., personalized content, interactive communication), they reciprocate with loyalty and relationship-building behaviors. Relationship equity thus reflects the consumer’s long-term reciprocal return—an outcome of sustained value exchange between the customer and brand. Empirical studies support the positive link between CE and relationship-based outcomes in services [

25,

26]. Hence, we propose the following:

H5. Banks’ CE positively influences relationship equity.

In addition to CE, relational benefits are essential in shaping relationship equity. Seminal and recent works on relational benefits emphasize the crucial role of social, special treatment, and confidence benefits for service brands to build and maintain strong customer connections [

33,

44]. These benefits are conceptualized as intermediate relational rewards that consumers receive in response to the brand’s ongoing value offerings. As consumers perceive emotional connection (social benefits), preferential treatment (STB), and reduced uncertainty (confidence benefits), they evaluate the relationship as more valuable and trustworthy. According to SET, this perceived value encourages consumers to reciprocate with deeper loyalty and commitment—ultimately strengthening relationship equity. Empirical studies also support these associations, showing that relational benefits foster personal bonds and long-term attachment to service brands [

42,

43]. Yuan et al. [

53] also demonstrated that value-laden relationships predict relationship equity, further supporting this theoretical framing. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6. Banks’ social benefits positively influence relationship equity.

H7. Banks’ STBs positively influence relationship equity.

H8. Banks’ confidence benefits positively influence relationship equity.

We developed a conceptual framework based on the literature review and proposed hypotheses, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

5. Discussion

The findings confirm that SMMA has a positive influence on CE. The findings corroborate the existing literature, such as Fetais, Algharabat, Aljafari, and Rana [

3], and Zeqiri, Koku, Dobre, Milovan, Hasani, and Paientko [

10], who found that SMMA increased CE on social media. Similarly, SMMA factors, such as customization, interaction, and trendy content, strengthen user engagement and brand relationships [

11]. The results also align with SET, which rests on the principle that consumers participate in exchange relationships based on reciprocal benefits [

28]. Accordingly, brands’ SMMA acts as an initial value offering by providing customization, direct brand interaction, expanded reach through word-of-mouth, relevant and up-to-date offerings, and entertaining content. In response, customers actively participate with the brand to exchange this value, and regarding services, customization, and promotional activities, foster CE on social media [

14,

20,

25]. Thus, the findings that banks can use social media to educate, personalize, and connect with customers enhances our knowledge of SMMA-CE associations in a broader relationship marketing context.

It was found that SMMA positively predicts relational benefits. This outcome underscores that marketing science has been re-oriented such that marketing success benefits customers as well as the company’s profit [

19]. Specifically, we found SMMA’s positive effects on three dimensions of relational benefits: social, STB, and confidence benefits, which are also aligned with the SET paradigm. Service brands leverage SMMA to foster consumer connections through valuable information, personalized support, and community engagement. These efforts enhance trust and belongingness and foster social benefits. Likewise, in service industries, SMMAs are likely to improve relationship quality [

4,

42]. This implies that SMMA by banks can strengthen social bonds with customers through interactive content, customer reviews, regular updates, and customized communication.

Likewise, building on SET, service brands can use SMMA to give customized content, personalized interactions, and special offers, ultimately improving customer experience and boosting STBs. This aligns with Gil-Saura, Ruiz-Molina, Berenguer-Contrí, and Seric [

43], who found that STBs are perceived as rewards for loyalty. Similarly, customized promotions and exclusive content rewards are linked to enhanced STB in the banking sector. These initiatives make customers feel more valued, leading to stronger loyalty and engagement with the service brands [

45,

47]. Regarding confidence benefits from the SET perspective, the SMMA gives customers a clear idea of what to expect from the service provider through regular, positive interaction, reinforcing the confidence benefits. This aligns with the findings of Jamil and Qayyum [

31], who demonstrated that online brand marketing activities are associated with increased buyer trust. Likewise, SMMA by service brands enhances relationship quality [

4], inducing confidence. Thus, clear and consistent communication by banks on social media can reassure customers about their credibility and competence, reinforcing consumer confidence. In contrast to existing research on the SMMA’s effect on the overall relational benefits, the present study empirically and theoretically validates this relationship, which extends our knowledge of the subject matter.

While previous research predominantly focused on the outcomes of relationship equity [

24,

26], relatively less attention has been given to understanding its antecedents. We identified two key drivers: CE and relational benefits. First, we found a significant effect of CE on RE. Previously, Akter, Mohiuddin Babu, Hossain, Dey, Liu, and Singh [

25], and Ho and Chung [

26] suggested the possible association between CE and RE in the service industry. The relationship is also supported by SET, which is relevant to understanding the benefits derived from CE in service brands [

14,

52]. These outcomes imply that personalized engagement and trust-building through CE enhance customer loyalty and investment in banks, boosting relationship equity.

Similarly, we found that relational benefits (except STBs) are significant drivers of relationship equity. Regarding this outcome, the related studies emphasized the pivotal role of relational benefits (social and confidence) in harnessing and sustaining strong customer connections [

33,

44]. The application of SET shows that social and confidence benefits are rewards consumers receive for their loyalty and engagement. Increased perception of social connection and confidence in the brand enhances relationship equity. Empirical research also depicts that relational bonds with service providers strengthen relationships [

43], whereas value-laden relationships predict relationship equity [

53]. Therefore, the present outcomes indicate that tailored services, exclusive offers, and prompt bank support foster trust and loyalty, deepening the customer–bank relationship.

In contrast, the effect of STBs on relationship equity was not statistically significant, which may be explained through both theoretical and contextual lenses. From the perspective of SET, relational benefits that offer emotional or symbolic value, such as social and confidence benefits, may foster stronger perceptions of reciprocity and trust. In the banking context, however, special treatment (e.g., discounts or priority service) is often standardized, perceived as an entitlement rather than an exclusive privilege. This reduces its perceived value and its ability to enhance relationship equity. This also aligns with Jamil, Qayyum, Ahmad, and Shah [

38], who demonstrated that the presence of stronger social variables sometimes reduces the predictive power of other variables. Further, a post-hoc model excluding the social benefits was tested. In this alternate model, the path from STBs to relationship equity became significant (β = 0.27,

p = 0.001), suggesting a potential suppression effect of social benefits on STBs. This outcome reinforces the idea that emotional and symbolic relational benefits (e.g., social and confidence benefits) may exert a stronger influence on equity perceptions compared to transactional benefits such as STB. See

Appendix D for details.

Grounded in SET, the cost benefit and reciprocity mechanisms that underpin consumer–brand relationships are consistent with the significant paths observed in our model. The effect of SMMA on CE, social benefits, and confidence benefits reflects the consumer perception that interactive, personalized, and entertaining brand communication on social media adds value, justifying reciprocal engagement and trust. These marketing initiatives function as relational investments, encouraging customers to exhibit loyalty-enhancing behaviors. Likewise, the positive effects of CE, social benefits, and confidence on relationship equity support the principle of reciprocal benefit, which states that emotional connection, trust, and recognition are reciprocated with stronger relational connections. Conversely, the non-significant effect of STBs on relationship equity might indicate a boundary condition in the SET framework. For instance, STBs such as fee waivers and faster service are standardized and expected practices in banking, thus failing to indicate exclusive reciprocity or value-added exchange. Importantly, this SET-based interpretation is consistent with the suppression effect identified in our post-hoc analysis (

Appendix D), where the presence of stronger social benefits diminished the apparent contribution of STBs. Together, these results suggest that transactional perks may lose salience in regulated contexts when emotional and symbolic benefits dominate perceptions of relational exchange.

Contextually, prior studies also reported mixed findings on the impact of STBs, particularly in high-involvement service sectors such as finance, where emotional trust and perceived risk management (confidence benefits) take precedence over material incentives [

70,

71]. It is also possible that moderating factors such as culture [

50] and prior service quality perceptions [

72] influence how STBs contribute to relationship equity. Alternatively, mediation through variables, such as perceived fairness or satisfaction, may explain indirect effects [

73] that were not captured directly.

Finally, experimental manipulation confirmed more significant outcomes of SMMA when consumers were exposed to social media ads (compared to no ads). This is similar to the findings of Qayyum, Jamil, Shah, and Lee [

18], elaborating that social media ads substantially influence consumer decisions by establishing profound emotional and cognitive connections through immersive, captivating content. Social media ads effectively capture consumer attention and deliver messages through rich multimedia formats, combining text, images, and videos [

40]. Additionally, the extant research has shown differential outcomes in CE [

18] and brand relationships [

15] based on experimental manipulations. Social media ads boost brand visibility and remind customers of the bank’s offerings. This inculcates increased CE and receptivity to personalized promotions, strengthening the customer–bank relationship.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This paper makes several theoretical contributions to social media and relationship marketing literature, particularly in banking. First, it responds to calls for exploring how SMMA strengthens customer–brand relationships by empirically validating its influence on CE and relational benefits [

5]. While prior studies emphasized loyalty and customer equity, this study reveals the intermediate mechanisms that lead to stronger relationship outcomes. Second, this research identifies CE and relational benefits—primarily social and confidence benefits—as key drivers of relationship equity. In doing so, it fills a gap in existing models that focused on the outcomes of relationship equity without addressing its antecedents [

74,

75].

Third, this research makes a theoretical contribution to social media and relationship marketing by using SET to explain how SMMA cultivates CE, relational benefits, and relationship equity. To date, most research examined the effects of SMMA on relationship-oriented outcomes using various theoretical lenses such as SOR [

4,

6,

8,

9], ELM [

8], social identification theory [

7], lovemark theory [

3], and self-concept theory [

5]. However, SET is particularly suited for interpreting CE and relational constructs, especially in service contexts [

75]. Scholars emphasized the need to apply relationship-oriented theories, such as SET, in SMMA research [

76,

77]. Therefore, this study adopts SET as the foundational theory demonstrating the mechanism through which SMMA drives CE, relational benefits, and ultimately relationship equity.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study offers several key insights for managers of service businesses, specifically banks, to devise SMMA strategies that enhance CE, relational benefits, and relationship equity. First, the findings reveal that social and confidence benefits significantly drive relationship equity. Therefore, bank marketers should focus on building trust and an emotional connection. To strengthen social benefits, banks can host live Q&A sessions with financial advisors, create online community forums to foster customer interaction, and run social media campaigns that encourage user-generated content. Additionally, promoting loyalty programs with public recognition and engaging customers through interactive polls or quizzes on financial topics can further deepen social connections. For confidence benefits, strategies such as placing confirmation calls for high-value or suspicious transactions, providing prompt issue resolution via social media, and regularly sharing fraud prevention tips help reinforce reliability. Banks should also share expert financial advice from trusted professionals and highlight compliance with security standards and certifications. Together, these steps can meaningfully enhance social and confidence benefits, ultimately fortifying long-term customer–bank relationships.

Second, the multigroup analysis indicates that exposure to social media ads significantly enhances CE, social benefits, and STB compared to no exposure. Banks should therefore invest more in personalized, data-driven social media advertising that is visually compelling and emotionally resonant. Rather than generic promotions, ad campaigns should be segmented based on customer demographics (e.g., age, income level) and behavioral insights (e.g., product usage, digital activity). Creative elements should highlight relatable financial scenarios, offer interactive tools (e.g., quick calculators, polls), and promote exclusive experiences to create a sense of connection and privilege. Such precision targeting can significantly amplify perceived value and engagement in digital banking ecosystems.

Third, the significant effect of CE on relationship equity underscores the importance of leveraging Facebook as a two-way communication platform rather than a mere content broadcast tool. Banks should utilize Facebook’s interactive features—such as polls, live video Q&A sessions, comment-based discussions, and personalized responses—to build authentic engagement with their audience. These efforts help foster trust and emotional connection, particularly with younger, educated users. By encouraging dialogue and demonstrating responsiveness, banks can reinforce customers’ sense of being valued, ultimately translating into stronger and more enduring relationship equity.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, although age was reported as part of the demographic profile, it was not examined as a moderating or control variable. Age can significantly influence how individuals interact with social media, perceive relational benefits, and engage with digital content. Younger individuals, for instance, tend to be more digitally savvy and receptive to online marketing efforts. Notably, the current sample had a mean age of approximately 26 years, with 82% of respondents aged 34 or below. Although recent studies relied upon younger respondents [

78], we believe that overlooking age as a moderating factor may have limited the depth of our analysis. Future research could examine the moderating role of demographic variables, such as age, given their potential influence on social media engagement behaviors and relational perceptions. Investigating generational or age-based differences could offer deeper insights into how diverse consumer segments respond to SMMA.

Second, this study focused exclusively on Facebook as the platform for stimulus exposure. As of early 2025, Facebook had approximately 60.4 million active users in Pakistan, compared to about 18.8 million Instagram users [

79], making Facebook significantly more dominant in terms of reach and audience diversity. While Facebook remains a widely used social media channel, user engagement patterns, content preferences, and interaction styles can vary significantly across platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, LinkedIn, and others. As a result, the findings may not fully reflect platform-specific nuances, and future research should explore how different social media environments influence the effectiveness of SMMA. A cross-platform analysis could reveal how different content formats, user demographics, and interaction mechanisms influence CE and relational outcomes.

Third, the scope of this research was limited to the banking sector, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other service industries. Applying the conceptual model to other service sectors such as healthcare, tourism, and education can improve generalizability.

Fourth, the study was conducted solely in Pakistan, which provides a specific cultural and regional context. Cultural norms, values, and digital behavior may differ significantly across countries, which could influence how consumers engage with brands on social media and perceive relational benefits. Therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to other cultural settings. Future studies should aim to replicate and validate the findings across diverse cultural and geographical settings. Differences in cultural norms, values, and social media usage patterns may shape how consumers perceive and respond to SMMA, making cross-cultural validation essential for enhancing external validity.

Lastly, although a between-subjects experimental design was employed to strengthen causal inference, it may not fully capture the dynamic and evolving nature of relational constructs, such as engagement and relationship equity, over time. Therefore, longitudinal experimental designs are recommended to capture the temporal development of engagement and relationship equity over time.