Rehumanizing AI-Driven Service: How Employee Presence Shapes Consumer Perceptions in Digital Hospitality Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Service Dehumanization

2.2. Symbolic Interactionalism Theory &Service Dehumanization in the Context of SSTs

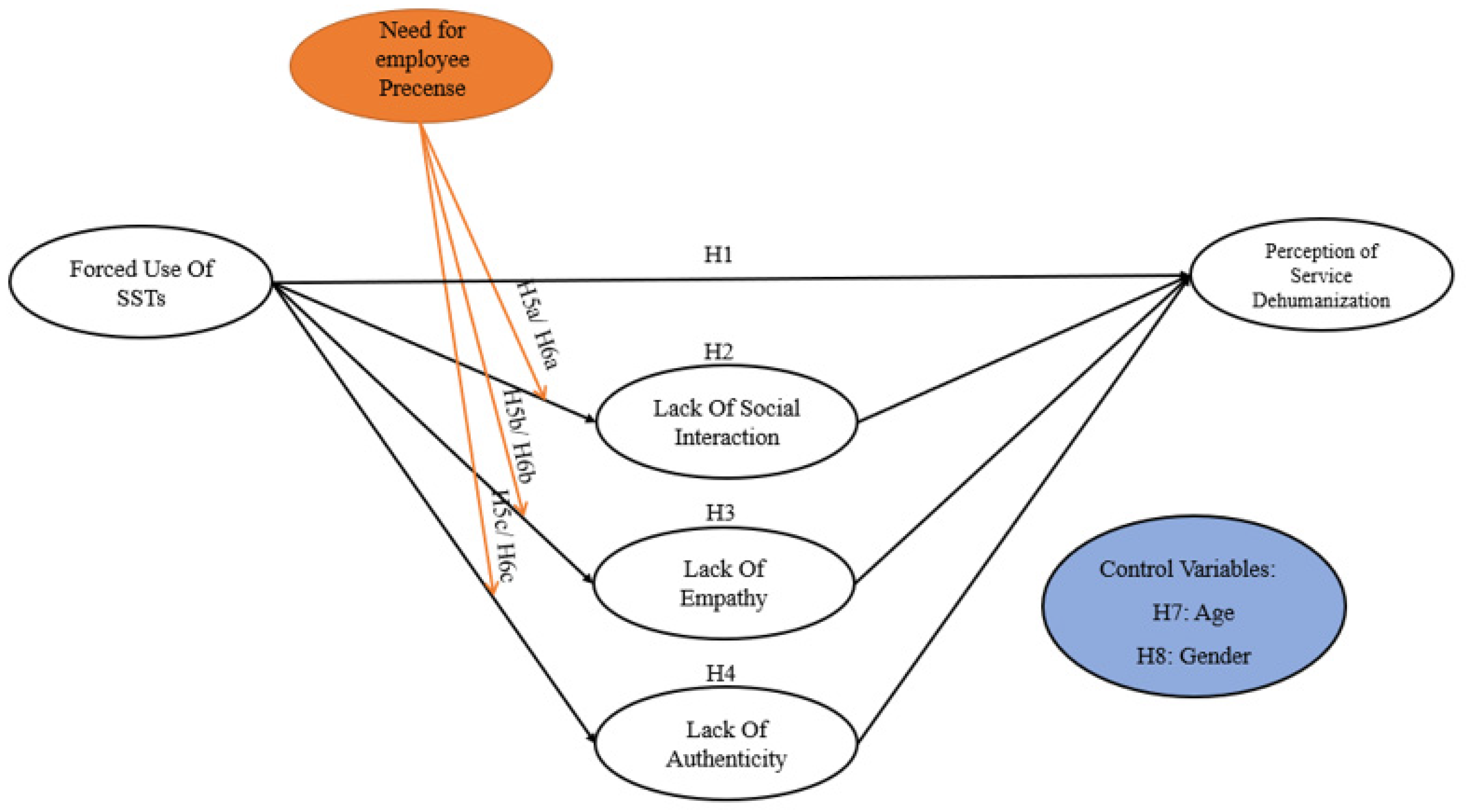

2.3. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Forced Use of SSTs

2.3.2. Lack of Social Interaction in the Context of SSTs

2.3.3. Lack of Empathy in the Context of SSTs

2.3.4. Lack of Authenticity in the Context of SSTs

2.3.5. Need for Employee Presence

2.3.6. Age Differences

2.3.7. Gender Differences

3. Method

3.1. Sample Recruitment and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Items and Survey Design

4. Results

4.1. CFA Results

4.2. Hypotheses Testing Results

4.2.1. Indirect Effect

4.2.2. Moderation Results

4.2.3. Moderated Mediation Results

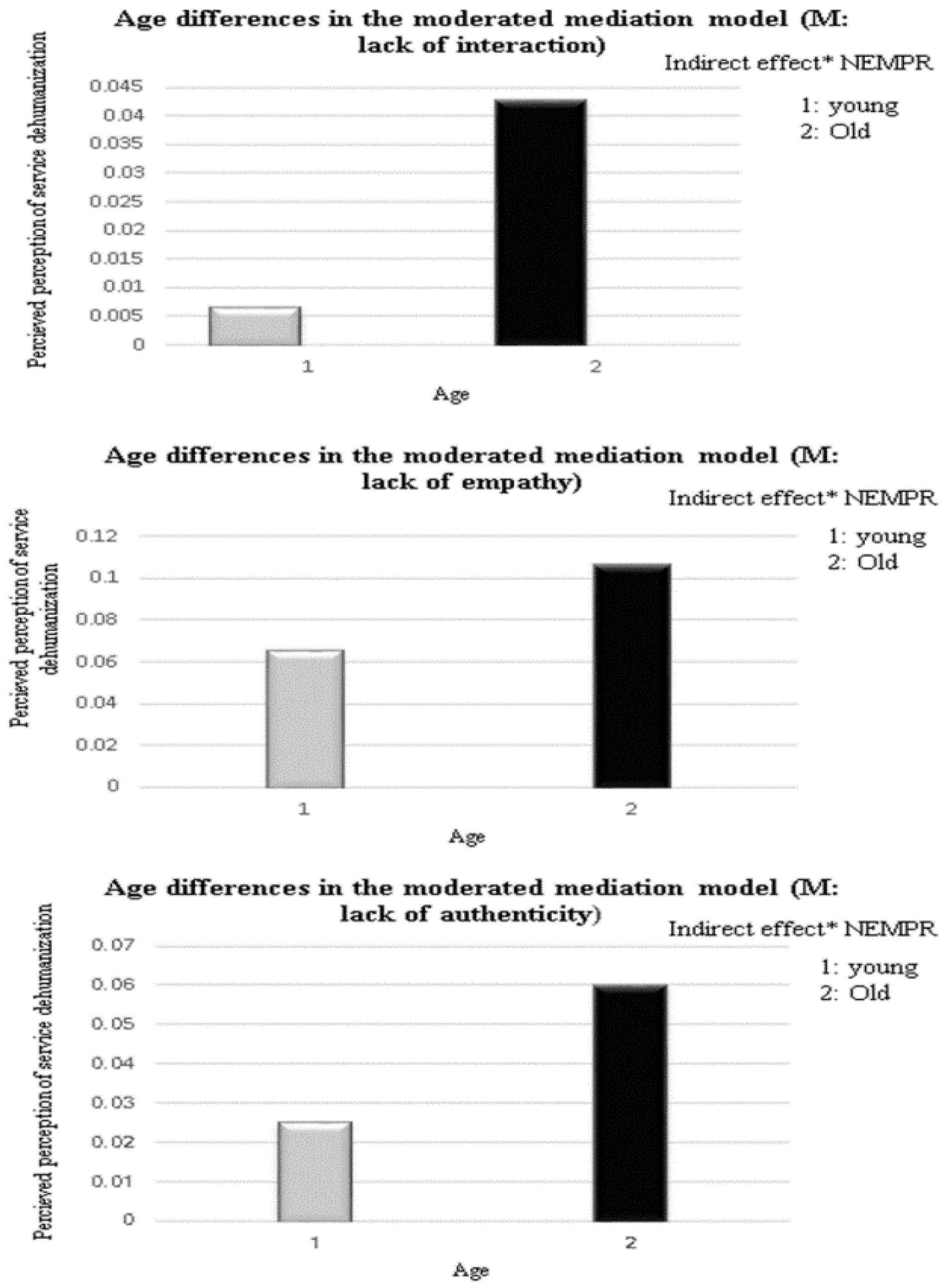

4.2.4. Age Group Comparison Results

4.2.5. Gender Comparison Results

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Theoretical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lubbe, I.; Roberts-Lombard, M.; Langerman, J. Millennials’ experiences and satisfaction with chatbots: A study of self-service technology in emerging markets. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Tu, R.; Lu, T.; Zhou, Z. Understanding forced adoption of self-service technology: The impacts of users’ psychological reactance. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwen, L.; Kwon, J.; Ahn, J. Self-Service Technology in the Hospitality and Tourism Settings: A Critical Review of the Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 46, 1220–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-E. Humanlike robots as employees in the hotel industry: Thematic Content Analysis of online reviews. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 29, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.M.; Sung, H.J.; Kim, H.Y. Customers’ acceptance intention of self-service technology of restaurant industry: Expanding UTAUT with perceived risk and innovativeness. Serv. Bus. 2020, 14, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L.; Ahn, J. Importance of voluntary usage among customers with difficulty using self-service technology (SST). Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2025, 35, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Yoon, S. When does self-service technology help employee work engagement? The moderating role of service type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, V.; Simon, F. Self-construal as the locus of paradoxical consumer empowerment in self-service retail technology environments. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yi, Y. The impact of self-service versusinterpersonal contact on customer–brand relationship in the time of Frontline Technology Infusion. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 39, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Zhuang, W.; Wang, L. An empirical analysis of self-service technologies: Mediating role of customer powerlessness. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 36, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. Male and female consumer decision-making styles. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Fundam. 2023, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brison, N.; Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Caesens, G. How supervisor and coworker ostracism influence employee outcomes: The role of organizational dehumanization and organizational embodiment. Balt. J. Manag. 2024, 19, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gip, H.; Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A.; Khoa, D.T. How organizational dehumanization Impacts Hospitality Employees Service Recovery Performance and Sabotage Behaviors: The role of psychological well-being and tenure. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 64–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, L.; Sarwar, A. When and why organizational dehumanization leads to deviant work behaviors in hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Hoegg, J.; Dahl, D.W. How consumers respond to embarrassing service encounters: A dehumanization perspective. J. Mark. Res. 2023, 60, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zheng, Y.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. “They” threaten my work: How AI service robots negatively impact frontline hotel employees through organizational dehumanization. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 128, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelibolu, M.; Mouloudj, K. Motivators and Demotivators of Consumers’ Smart Voice Assistant Usage for Online Shopping. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y. I can be myself: Robots reduce social discomfort in hospitality service encounters. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 36, 1798–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitouni, M.; Murphy, K.S. Self-Service Technologies (SST) in the US Restaurant industry: An evaluation of consumer perceived value, satisfaction, and continuance intentions. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2025, 28, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Bagozzi, R.P. An attitudinal model of technology-based self-service: Moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-M.; Sim, M.; Kang, M.; Kang, H.; Jang, J.; Kim, D. Effects of perceived risk and consumer characteristics on the continuous use intention of technology-based Self Service. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 30, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Dai, B. The efficacy of customer’s voluntary use of self-service technology (SST): A Dual-Study Approach. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 30, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwan, C.; Budd, L.; Ison, S. A systematic literature review of passenger non-adoption of airport self-service technologies: Issues and future recommendations. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Lee, H.-K. AI Recommendation Service Acceptance: Assessing the Effects of Perceived Empathy and Need for Cognition. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1912–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galičić, V.; Ivanović, S. Dehumanization of hospitality industry using information-communication technologies. Informatologia 2007, 40, 223–228. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/21518 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Blumer, H. Mead and Blumer: The convergent methodological perspectives of social behaviorism and symbolic interactionism. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1980, 45, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kim, D.; Hyun, H. Understanding self-service technology adoption by “older” consumers. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 35, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, Y.; Kwon, B. Does user burden matter? Age differences in user behavior of self-service technology. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 6047–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagu, A.; Matson, F.W. The Dehumanization of Man; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1983; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA07067706 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Haslam, N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, A.P.; Boegershausen, J.; Hoegg, J.; Aquino, K.; Lemmink, J. Discounting humanity: When consumers are price conscious, employees appear less human. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L. Defining Dehumanization. In On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Parasuraman, A.; Grewal, D.; Voss, G.B. The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Sparks, B.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Zapf, D. Service encounter needs theory: A dyadic, psychosocial approach to understanding service encounters. In Research on Emotion in Organizations; Ashkanasy, N.M., Humphrey, R.H., Troth, A.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2010; pp. 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.S.; Chan, B. “Service with a smile” and emotional contagion: A replication and extension study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Roundtree, R.I. The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G.H. Mind, Self, and Society; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.-M. Ann Satterthwaite, going shopping: Consumer choices and community consequences (London: Yale University Press, 2001, $45.00). pp. 386. ISBN 0 300 08421 8. J. Am. Stud. 2004, 38, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Lawlor, J.; Mulvey, M. Customer roles in self-service technology encounters in a tourism context. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 34, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, M.J.; Dabholkar, P.A.; Frambach, R.T. Consequences of forcing consumers to use technology-based self-service. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 11, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B.R. Effects of service authenticity, customer participation and customer-perceived service climate on customers’ service evaluation. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, E.; Cikara, M. Strategic Regulation of Empathy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. The impact of forced use on customer adoption of self-service technologies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, M.J.; Frambach, R.; Kleijnen, M. Mandatory use of technology-based self-service: Does expertise help or hurt? Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, S.; Elms, J.; Moore, S. Exploring the adoption of self-service checkouts and the associated social obligations of shopping practices. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 42, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ying, T.; Liu, X. Echoes of Innovation: Exploring the Use of Voice Assistants to Boost Hotel Reputation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granulo, A.; Fuchs, C.; Puntoni, S. Preference for human (vs. robotic) labor is stronger in symbolic consumption contexts. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 31, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E.; Sherrell, D.L. Examining the influence of control and convenience in a self-service setting. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 38, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Kim, J.E.; Moon, J.; Nam, E.W. Social engagement and subjective health among older adults in South Korea: Evidence from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006–2018). SSM Popul. Health 2023, 21, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinyoung, N.; Seongcheol, K. Why do elderly people feel negative about the use of self-service technology and how do they cope with the negative emo-tions? In Proceedings of the 31st European Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): “Reining in Digital Platforms? Challenging Monopolies, Promoting Competition and Developing Regulatory Regimes”, Gothenburg, Sweden, 20–21 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Junco, N. Advancing the sociology of empathy: Aproposal. Symb. Interact. 2017, 40, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. The influence of empathy in complaint handling: Evidence of attitudinal and transactional routes to loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, A.; Sharkey, N. Granny and the Robots: Ethical Issues in Robot Care for the elderly. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2010, 14, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.L. Empathy-based marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, C.; Cain, J. The emerging issue of digital empathy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.M.; Ren, L.; Chen, C. Customers’ perception of the authenticity of a Cantonese restaurant. J. China Tour. Res. 2017, 13, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A.L.; Eilert, M. Signaling Authenticity for Frontline Service Employees. J. Serv. Mark. 2021, 36, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F. Teaching old brands new tricks: Retro branding and the revival of Brand meaning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoller, D. Skilled Perception, Authenticity, and the Case Against Automation; Oxford Scholarship Online; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Cristancho-Lacroix, V.; Fassert, C.; Faucounau, V.; de Rotrou, J.; Rigaud, A.-S. The attitudes and perceptions of older adults with mild cognitive impairment toward an assistive robot. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2014, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, J.E.; Kimes, S.E. Only if it is convenient. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Unlock Happy Interactions: Voice Assistants Enable Autonomy and Timeliness. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejdys, J.; Gulc, A. Factors influencing the intention to use assistive technologies by older adults. Hum. Technol. 2022, 18, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoulin, N.T.; Djelassi, S. An integrated model of self-service technology (SST) usage in a retail context. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 540–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudj, K.; Aprile, M.C.; Bouarar, A.C.; Njoku, A.; Evans, M.A.; Oanh, L.V.L.; Asanza, D.M.; Mouloudj, S. Investigating Antecedents of Intention to Use Green Agri-Food Delivery Apps: Merging TPB with Trust and Electronic Word of Mouth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qu, H.; Hsu, M.K. Toward an integrated model of tourist expectation formation and gender difference. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Madson, L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 122, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Fairhurst, A.; Cho, H.J. Gender differences in consumer evaluations of service quality: Self-service kiosks in retail. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kang, J. High-Tech Convenience Stores Boom Amid High Labor Costs and Contactless Services; Yonhap News Agency: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022; Available online: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20220701004100320 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Almokdad, E.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Lee, C.H. Antecedents of booster vaccine intention for domestic and International Travel. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Lee, C.H. The effect of real-time crowding information on tourists’ procrastination of planned travel schedule. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Factor Analysis: Classic Edition; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, K.A.; Popovich, D. When big is less than small: Why dominant brands lack authenticity in their sustainability initiatives. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, V.; Baber, H.; Shukla, B.; Sujatha, R.; Khan, D. Does lack of social interaction act as a barrier to effectiveness in work from home? COVID-19 and gender. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2023, 10, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, R.E.; Minton, A.P.; Reid, D.A. A short measure of perceived empathy. Psychol. Rep. 1996, 79 (Suppl. S3), 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Zach, F.J.; Wang, J. Attitudes Toward Autonomous on Demand Mobility System: The Case of Self-Driving Taxi. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Schegg, R., Stangl, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, J.; Syed, D. Techniques to deal with missing data. In Proceedings of the 2016 5th International Conference on Electronic Devices, Systems and Applications (ICEDSA), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 6–8 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Green, S.B. The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2016, 51, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 151 | 50.2 |

| Female | 149 | 49.8 | |

| Age | Old | 150 | 50 |

| Young | 150 | 50 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 74 | 24.7 |

| Married | 201 | 67.2 | |

| Divorced | 17 | 5.7 | |

| Widowed | 8 | 2.4 | |

| Frequency of use of SSTs in the last three months | 1–5 | 98 | 32.8 |

| 6–10 | 157 | 52.5 | |

| 11–20 | 36 | 12.0 | |

| More than 20 times | 9 | 2.8 | |

| Educational Background | High school or below | 17 | 5.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 265 | 88.4 | |

| Master’s degree | 7 | 2.3 | |

| Doctorate | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Others | 7 | 2.3 | |

| Mandatory self-service | Hotel | 148 | 49.5 |

| Restaurant | 91 | 30.4 | |

| Tourism attraction | 48 | 16.1 | |

| Others | 13 | 4.1 |

| Factors | Factor Loading | CR | Eigenvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced use of SSTs | 0.900 | 1.223 | |

| Only self-service facilities were available. | 0.845 | ||

| I had less freedom to choose a service-delivery mode. | 0.897 | ||

| Service provider imposed a self-service technology on me. | 0.900 | ||

| Lack of social interaction | 0.854 | 2.011 | |

| I felt isolated when I forced to use self-service machines. | 0.782 | ||

| The forced use of self-service machines limited my interaction with employees. | 0.813 | ||

| When I forced to use self-service machines, I found them more impersonal compared to traditional service. | 0.814 | ||

| I missed the social cues from employees when I forced to use self-service machines. | 0.803 | ||

| There was a lack of employee collaboration when I was forced to use self-service machines. | 0.834 | ||

| I preferred to interact with employees than interacting with machine where there was no social interaction. | 0.833 | ||

| Lack of empathy | 0.833 | 3.221 | |

| When I forced to use self-service machines, I felt they failed to comprehend my needs. | 0.848 | ||

| I experienced negative emotions, when forced to interact with self-service machines. | 0.827 | ||

| The forced use of self-service machines could not grasp the emotional aspect of my service experience. | 0.845 | ||

| I did not feel in sync with the self-service machine when its use was imposed on me. | 0.848 | ||

| When I was compelled to use them, self-service machines couldn’t understand my thought process. | 0.847 | ||

| When discussed my purchases and forced to use self-service machines, they didn’t sense what I truly needed. | 0.843 | ||

| Self-service machines, when their used was mandated, seemed out of touch with the intricacies of the service I required. | 0.820 | ||

| Due to their enforced usage, self-service machines lacked insight into my decision-making needs. | 0.809 | ||

| Lack of authenticity | 0.877 | 2.998 | |

| When I was forced to use self-service machines, I felt the actions of machines were not genuine. | 0.857 | ||

| When I was forced to use self-service machines, their service didn’t come across as credible. | 0.838 | ||

| The forced use of self-service machines didn’t align with the authentic service values I expected. | 0.835 | ||

| Service dehumanization | 0.867 | 3.523 | |

| In my opinion, the forced use of self-service machines dehumanized the service environment. | 0.856 | ||

| In my opinion, the forced use of self-service machines in service sectors could pose risks to human well-being. | 0.831 | ||

| In my opinion, the forced use of self-service machines diminished the value of roles traditionally held by humans. | 0.836 | ||

| In my opinion, the mandated use of self-service machines could make people feel subservient to technology. | 0.816 | ||

| In my opinion, the forced use of self-service technologies reduced individuals to mere statistics or numbers. | 0.826 | ||

| Need for employee presence | 0.898 | 3.121 | |

| I would like to be able to see an employee while using the technology. | 0.921 | ||

| I would feel the service experience as more genuine and emotional if an employee is close while I use the self-service machines | 0.832 | ||

| Having an employee present in the technology area would enhance my technology experience. | 0.844 | ||

| Having an employee near the self-service machines would make me feel more confident about my technology experience. | 0.859 |

| FCDSST | LOAUT | LOITR | LOEMP | NEMPR | PSVDH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCDSST | 0.913 a | |||||

| LOAUT | 0.267 * b | 0.822 | ||||

| LOITR | 0.218 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.791 | |||

| LOEMP | 0.224 * | 0.466 * | 0.540 * | 0.814 | ||

| NEMPR | 0.015 * | 0.315 * | 0.490 ** | 0.410 ** | 0.912 | |

| PSVDH | 0.194 * | 0.511 * | 0.455 * | 0.602 * | 0.540 ** | 0.805 |

| AGE | 0.045 * | 0.114 * | 0.091 * | 0.118 * | 0.054 | 0.592 * |

| Gender | 0.034 * | 0.211 * | 0.113 * | 0.023 * | 0.045 * | 0.012 * |

| AVE | 0.834 | 0.676 | 0.626 | 0.663 | 0.831 | 0.647 |

| VIF | 4.817 | 4.205 | 4.817 | 5.502 | 4.078 | - |

| Indirect Effect of FCDSST on PSVDH | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Coefficient | SE | p | t | LLCI | ULCI | Conclusion |

| Direct effect: FCDSST →PSVDH | 0.141 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 3.412 | 0.060 | 0.223 | - |

| Indirect effect: FCDSST →PSVDH | 0.024 | 0.014 | 0.104 | 1.627 | −0.004 | 0.050 | - |

| M1: LOITR | 0.216 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 4.588 | 0.124 | 0.309 | Complete mediation |

| M2: LOEMP | 0.541 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 5.302 | 0.435 | 0.647 | Complete mediation |

| M3: LOAUT | 0.249 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 10.055 | 0.157 | 0.342 | Complete mediation |

| Explained Variable | FCDSST × NEMPR | B | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (−1 SD) = 2.9 | 0.039 | 0.024 | −0.009 | 0.088 | |

| LOITR | Moderate = 4.2 | 0.140 | 0.018 | 0.103 | 0.177 |

| High (+1 SD) = 5.5 | 0.241 | 0.027 | 0.186 | 0.296 | |

| Low (−1 SD) = 2.9 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.055 | 0.057 | |

| LOEMP | Moderate = 4.2 | 0.155 | 0.020 | 0.114 | 0.196 |

| High (+1 SD) = 5.5 | 0.309 | 0.030 | 0.250 | 0.368 | |

| Low (−1 SD) = 2.9 | 0.057 | 0.027 | 0.002 | 0.111 | |

| LOAUT | Moderate = 4.2 | 0.188 | 0.022 | 0.144 | 0.232 |

| High (+1 SD) = 5.5 | 0.319 | 0.034 | 0.251 | 0.387 |

| Explained Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of Interaction | Perception of Service Dehumanization | |||||||

| B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| FCDSST | 0.193 | 0.061 | 0.073 | 0.312 | 0.024 | 0.014 | −0.004 | 0.050 |

| NEMPR | 0.469 | 0.054 | 0.361 | 0.576 | ||||

| IN | 0.078 | 0.014 | 0.050 | 0.107 | ||||

| LOITR | 0.216 | 0.047 | 0.124 | 0.309 | ||||

| MOD-MED-INX | 0.017 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.027 | ||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Explained Variables | ||||||||

| Lack of Empathy | Perception of Service | |||||||

| Dehumanization | ||||||||

| B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| FCDSST | 0.353 | 0.070 | 1.019 | 1.725 | 0.024 | 0.014 | −0.004 | 0.050 |

| NEMPR | 0.342 | 0.061 | 0.222 | 0.462 | ||||

| IN | 0.120 | 0.016 | 0.088 | 0.151 | ||||

| LOEMP | 0.541 | 0.051 | 0.435 | 0.647 | ||||

| MOD-MED-INX | 0.065 | 0.011 | 0.044 | 0.088 | ||||

| p < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Explained Variables | ||||||||

| Lack of Authenticity | Perception of Service Dehumanization | |||||||

| B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | |||

| LLCI | ULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| FCDSST | 0.245 | 0.070 | 0.132 | 0.622 | 0.024 | 0.014 | −0.004 | 0.050 |

| NEMPR | 0.415 | 0.065 | 0.286 | 0.545 | ||||

| IN | 0.105 | 0.017 | 0.068 | 0.135 | ||||

| LOAUT | 0.249 | 0.045 | 0.157 | 0.342 | ||||

| MOD-MED-INX | 0.025 | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.039 | ||||

| R2 = 0.888 | ||||||||

| p < 0.001 | df = 340.53, p < 0.001 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almokdad, E.; Mouloudj, K.; Lee, C.H. Rehumanizing AI-Driven Service: How Employee Presence Shapes Consumer Perceptions in Digital Hospitality Settings. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030209

Almokdad E, Mouloudj K, Lee CH. Rehumanizing AI-Driven Service: How Employee Presence Shapes Consumer Perceptions in Digital Hospitality Settings. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030209

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmokdad, Eeman, Kamel Mouloudj, and Chung Hun Lee. 2025. "Rehumanizing AI-Driven Service: How Employee Presence Shapes Consumer Perceptions in Digital Hospitality Settings" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030209

APA StyleAlmokdad, E., Mouloudj, K., & Lee, C. H. (2025). Rehumanizing AI-Driven Service: How Employee Presence Shapes Consumer Perceptions in Digital Hospitality Settings. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030209