When Interaction Becomes Addiction: The Psychological Consequences of Instagram Dependency

Abstract

1. Introduction

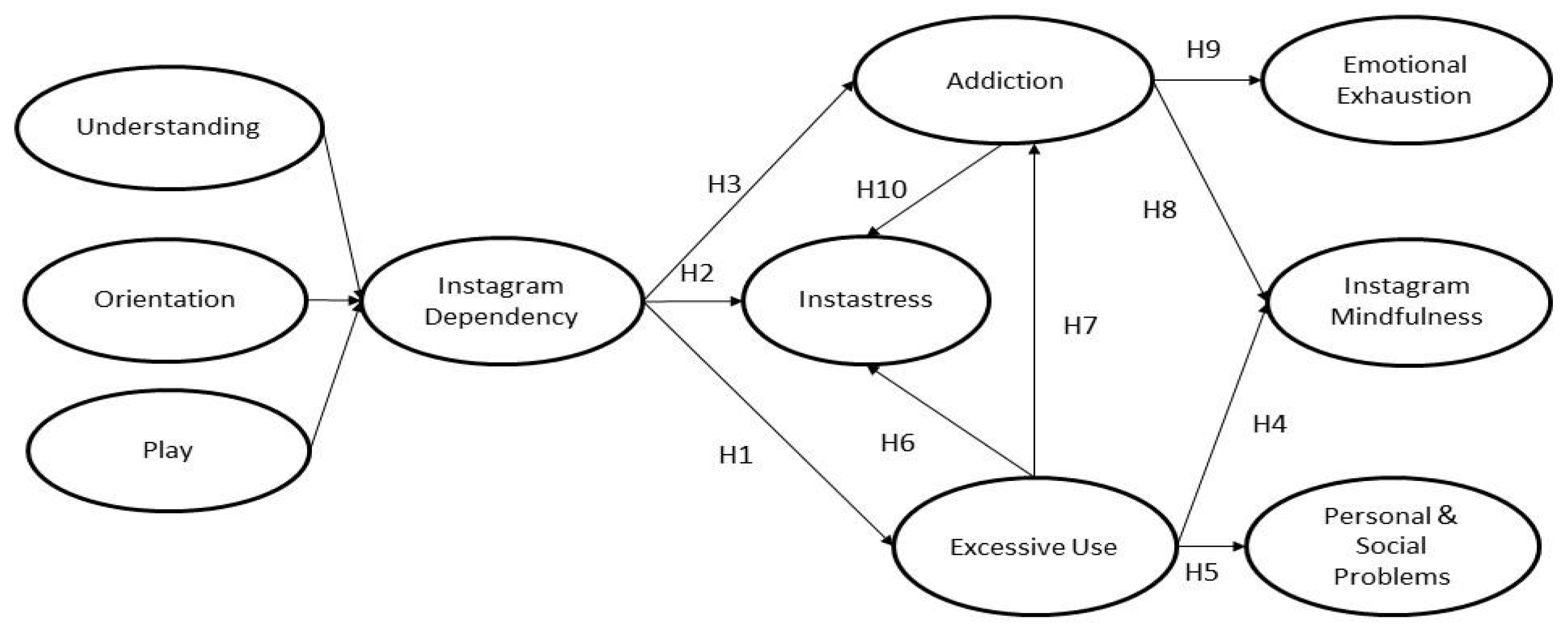

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Direct Negative Outcomes of Instagram Dependency

2.2. Indirect Negative Outcomes of Instagram Dependency

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Structural Model Assessment

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDT | Media Dependency Theory |

| SNS | Social networks |

Appendix A. Scales

| Dependency (DEP) (formative) | |

| Social Understanding (SOU) | |

| SOU1 | To keep up with what is happening with my closest friends and family. |

| SOU2 | To find out what is going on with my wide circle of acquaintances. |

| SOU3 | To stay on top with what is happening with celebrities, brands, etc. |

| Self-Understanding (SEU) | |

| SEU1 | To look back on my behaviour both online and offline. |

| SEU2 | To anticipate what may happen to me based on the experience of others. |

| SEU3 | To observe how others cope with problems or situations like mine. |

| Interaction Orientation (IO) | |

| IO1 | To communicate and interact with others. |

| IO2 | To know what to do in certain situations. |

| IO3 | To reach out to others in difficult times. |

| Action Orientation (AO) | |

| AO1 | To know where to find/buy what I like and need |

| AO2 | To get ideas on what to buy for me and for others. |

| AO3 | To know where to go in my leisure time. |

| Social Play (SP) | |

| SP1 | To share my thoughts and experiences with friends and relatives. |

| SP2 | To entertain myself with what is being posted by others. |

| SP3 | To be part of the events I like without being there. |

| Solitary Play (STP) | |

| STP1 | To relax after a hard day/week at work/school. |

| STP2 | To have quiet time on my own. |

| STP3 | To have something to do when no one else is around. |

| Addiction (ADD) (formative) | |

| ADD1 | I need to spend an increasing amount of time on Instagram to be satisfied. |

| ADD2 | I think about Instagram when I am offline and anticipate my next connection. |

| ADD3 | I have lied to friends or family members about the time I spent on Instagram. |

| ADD4 | I feel restless, moody, or irritable when I try to reduce or stop using Instagram. |

| ADD5 | I have repeatedly tried to control, reduce, or stop using Instagram unsuccessfully. |

| ADD6 | I turn to Instagram as a way to escape from my problems or relieve feelings of helplessness, anxiety or depression. |

| ADD7 | I spend more time on Instagram than initially intended. |

| ADD8 | I have compromised a significant social relationship, job, educational, or career opportunity because of my Instagram usage. |

| Excessive Use (EU) (reflective) | |

| EU1 | I think that the amount of time I spend on Instagram is more than I should be spending. |

| EU2 | I spend an unusually high amount of time on Instagram. |

| EU3 | I spend more time on Instagram than the average person. |

| Instastress (IST) (reflective) | |

| IST1 | I feel that the information I receive from Instagram intrudes my personal life. |

| IST2 | I spend less time with my family because of my Instagram usage. |

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) (reflective) | |

| EE1 | After spending time on Instagram, I feel emotionally exhausted. |

| EE2 | By the end of the day, I feel drained by the use of Instagram. |

| EE3 | I feel fatigued after being on Instagram. |

| EE4 | I feel stressed after consuming a large amount of posts, videos and user comments on Instagram. |

| Instagram Mindfulness (INM) (reflective) | |

| INM1 | I disconnect from everything else when I am on Instagram. |

| INM2 | When I am online, I find it difficult to focus on what is happening around me. |

| INM3 | I only half-listen to what people around me are saying while I am on Instagram. |

| INM4 | I open the Instagram app without thinking. |

| INM5 | I open the Instagram app automatically. |

| Negative Outcomes (NEGO) (reflective) | |

| NEGO1 | Sometimes, I neglect some social or non-social activities (such as sports, etc.) because of Instagram |

| NEGO2 | Sometimes, using Instagram makes it difficult for me to manage my life. |

| NEGO3 | Sometimes, my Instagram usage causes problems in my personal life. |

References

- DataReportal. Digital 2024: Deep Dive—The Time We Spend on Social Media. 2024. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-deep-dive-the-time-we-spend-on-social-media (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Nikolinakou, A.; Phua, J.; Kwon, E.S. What drives addiction on social media sites? The relationships between psychological well-being states, social media addiction, brand addiction and impulse buying on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 153, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Basic but Frequently Overlooked Issues in Manuscript Submissions: Tips from an Editor’s Perspective. J. Appl. Bus Behav. Sci. 2025, 1, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xu, C.; Ali, A. A socio-technical system perspective to exploring the negative effects of social media on work performance. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Lyu, C. The relationship between smartphone addiction and procrastination among students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2024, 224, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Iranmanesh, M.; Salamzadeh, Y. Associations between Instagram addiction, academic performance, social anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 2221–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, P.; Toth, F.; Castro, L.; Štětka, V.; Vreese, C.D.; Aalberg, T.; Cardenal, A.S.; Corbu, N.; Esser, F.; Hopmann, D.N.; et al. Does a crisis change news habits? A comparative study of the effects of COVID-19 on news media use in 17 European countries. Digit. J. 2021, 9, 1208–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaetz, N.; Gagrčin, E.; Toth, R.; Emmer, M. Algorithm dependency in platformized news use. New Media Soc. 2025, 27, 1360–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. (Ed.) The Palgrave Handbook of Interactive Marketing; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Chan, L.S.; Du, N.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.T. Gratification and its associations with problematic internet use: A systematic review and meta-analysis using Use and Gratification theory. Addict. Behav. 2024, 155, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berne Manero, M.D.C.; Moretta Tartaglione, A.; Russo, G.; Cavacece, Y. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth management in hotel ecosystem: Insights about managers’ decision-making process. J. Intellect. Cap. 2023, 24, 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Pérez-Ruiz, P. Building relational worth in an online social community through virtual structural embeddedness and relational embeddedness. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tayyab, S.M.U.; Luo, X.; Lee, F.C.; Jia, Q. Investigating social streaming app dependency: A mixed-methods analysis. J. Intellect. Cap. 2025, 26, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, R.R.; Yang, X. Examining compulsive use of social media: The dual effects of individual needs and peer influence. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 3109–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zanuddin, H.; Hou, W.; Xu, J. Media attention, dependency, self-efficacy, and prosocial behaviours during the outbreak of COVID-19: A constructive journalism perspective. Glob. Media China 2022, 7, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L.; Lin, J.; Sato, T.; Saboor, S.; Viswanath, K. Does social media use make us happy? A meta-analysis on social media and positive well-being outcomes. SSM Ment. Health 2024, 6, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Miquel-Romero, M.J. From Instagram overuse to Instastress and emotional fatigue: The mediation of addiction. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2019, 23, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, B. A Study of Instagram Dependency on Indian Youth: Assessing Its Impact on Students’ Lives; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4863982 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kovan, A.; Gülbahçe, A.; Salamzade, T. Beyond the Filter: Examining the Psychosocial Effects of Instagram Addiction. J. Concurr. Disord. 2024, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.P.; Chaudhary, R.; Thomas, J.; Menon, V.A. Assessing Instagram Addiction and Social Media Dependency among Young Adults in Karnataka. Stud. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B.; Hyun, S.S. Drivers and outcomes of Instagram Addiction: Psychological well-being as moderator. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmad, Y.E.; Budiyanto, B.; Khuzaini, K. Impact of Viral Marketing and Gimmick Marketing on Transformation of Customer Behavior Mediated by Influencer Marketing. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2025, 2, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, N.; Dhir, A. Social comparisons at social networking sites: How social Media-induced fear of missing out and envy drive compulsive use. Internet Res. 2025, 35, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial–What is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.D.; Rathore, D.B.; Kumari, R.; Das, S.; Goel, A.V. The role of social media dependence and social influence in shaping consumer trust and purchase intention. J. Mark. Soc. Res. 2025, 2, 108–116. Available online: https://jmsr-online.com/article/the-role-of-social-media-dependence-and-social-influence-in-shaping-consumer-trust-and-purchase-intention-140/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Patwardhan, P.; Yang, J. Internet dependency relations and online consumer behavior: A media system dependency theory perspective on why people shop, chat, and read news online. J. Interact. Advert. 2003, 3, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.E. Media dependency and multiple media sources. In The Psychology of Political Communication; Crigler, A., Ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1996; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N.; Zarei, H.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Ghasemi, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Mohammadi, M. The impact of social networking addiction on the academic achievement of university students globally: A meta-analysis. Public Health Pract. 2025, 7, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.W.; Lau, Y.H.; Leung, L.Y.; Li, E.K.; Ma, R.K. Enigma of social media use: Complexities of social media addiction through the serial mediating effects of emotions and self-presentation. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1448168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lee, M.K.; Hua, Z. A theory of social media dependence: Evidence from microblog users. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 69, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Arenas, M.D.P.; Díaz Pareja, E.M.; Ramírez García, A.; García Rojas, A.D. Motivaciones y contradicciones en el uso de las redes sociales en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Comun. 2024, 23, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talan, T.; Doğan, Y.; Kalinkara, Y. Effects of smartphone addiction, social media addiction and fear of missing out on university students’ phubbing: A structural equation model. Deviant Behav. 2024, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha Ortiz, J.A.; Santos Corrada, M.; Perez, S.; Dones, V.; Rodriguez, L.H. Exploring the influence of uncontrolled social media use, fear of missing out, fear of better options, and fear of doing anything on consumer purchase intent. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundel, J.; Wan, A.; Yang, J. Processes underlying social comparison with influencers and subsequent impulsive buying: The roles of social anxiety and social media addiction. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 30, 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrom, M.; Busalim, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Asadi, S.; Mohd Ali, R. The impact of excessive Instagram use on students’ academic study: A two-stage SEM and artificial neural network approach. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 3546–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiana, M.B.V.; Rajan, M.J.S. Technostress and users of emerging technologies in knowledge-based professions—An Indian outlook. Int. J. Electron. Bus. 2024, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Montani, F.; Jamal, A.; Shah, M.H. Consequences of technostress for users in remote (home) work contexts during a time of crisis: The buffering role of emotional social support. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Suhail, A.; Kautish, P.; Hakeem, M.M.; Rashid, M. Turning lemons into lemonade: Social support as a moderator of the relationship between technostress and quality of life among university students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 0, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naga, J.F.; Ebardo, R.A. Social network sites (SNS) an archetype of techno-social stress: A systematic review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.; Phoolka, S. Impact of social media usage on technostress among employees in IT sector. J. Strateg. Manag. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Qiang, T.; Kanliang, W. The Impact of Computer Self-Efficacy and Technology Dependence on Computer-Related Technostress: A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samarraie, H.; Bello, K.A.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Smith, A.P.; Emele, C. Young users’ social media addiction: Causes, consequences and preventions. Inf. Technol. People. 2022, 35, 2314–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opariuc-Dan, C.; Maftei, A.; Merlici, I.A. I Don’t matter anyway. Will more Instagram change that? Anti-mattering and Instagram Feed vs. stories addiction symptoms: The moderating roles of loneliness and life satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Bierhoff, H.W.; Rohmann, E. Materialism in social media–more social media addiction and stress symptoms, less satisfaction with life. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 13, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J. Social capital on mobile SNS addiction: A perspective from online and offline channel integrations. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; He, G.; Zheng, H.; Ai, J. What makes Chinese adolescents glued to their smartphones? Using network analysis and three-wave longitudinal analysis to assess how adverse childhood experiences influence smartphone addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 163, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, P.; Li, H.; Mao, N.; Hu, H.; Griffiths, M.D. Gender differences in the associations between parental phubbing, fear of missing out, and social networking site addiction: A cross-lagged panel study. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, Z.; Nabi, M.K.; Saleem, I. Unveiling the role of social media and females’ intention to buy online cosmetics. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, J.M.B.; Schoenfeld, A.S.G. Influencers y su impacto en los adolescentes, generación “z”. Rev. Cient. Tejedora 2023, 6, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudad-Fernández, V.; Zarco-Alpuente, A.; Escrivá-Martínez, T.; Herrero, R.; Baños, R. How adolescents lose control over social networks: A process-based approach to problematic social network use. Addict. Behav. 2024, 154, 108003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eşkisu, M.; Çam, Z.; Gelibolu, S.; Rasmussen, K.R. Trait mindfulness as a protective factor in connections between psychological issues and Facebook addiction among Turkish university students. Stud. Psychol. 2020, 62, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Y.; Pandey, J. Demystifying the dark side of social networking sites through mindfulness. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 25, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, W. The association between mindfulness and social media addiction among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Workplace Health Saf. 2025, 73, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwilai, K.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Face it, don’t Facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress Health 2016, 32, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewude, G.T.; Natnael, T.; Woreta, G.T.; Bezie, A.E. A multi-mediation analysis on the impact of social media and internet addiction on university and high school students’ mental health through social capital and mindfulness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Chemnad, K.; Al-Harahsheh, S.; Abdelmoneium, A.O.; Bagdady, A.; Hassan, D.A.; Ali, R. The influence of adolescents’ essential and non-essential use of technology and Internet addiction on their physical and mental fatigues. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ain, N.U.; Azeem, M.U.; Haq, I.U.; Mehmood, I. When does knowledge hiding hinder employees’ job performance? The roles of emotional exhaustion and emotional intelligence. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2024, 22, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, S.A.; Molnár, E. Navigating the digital divide: The impact of social media fatigue on work-life balance. Gradus 2024, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Â.; Rodrigues, A.; Ribeiro, A.M.; Lopes, S. Contribution of social media addiction on intention to buy in social media sites. Digital 2024, 4, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, E.A.C.P.; Wijesundara, W.M.T.H.; Athukorala, A.S.T.; Chithrananda, K.P.S.P. Role of social media dependency and online reputation in instituting stress among social media users. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2025, 14, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa-Blanco, M.; García, Y.R.; Landa-Blanco, A.L.; Cortés-Ramos, A.; Paz-Maldonado, E. Social media addiction relationship with academic engagement in university students: The mediator role of self-esteem, depression, and anxiety. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Social Media: 59% of EU Individuals Participate in Social Networks. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240319-1 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Statista. Social Media Usage in Europe—Statistics Facts. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/4106/social-media-usage-in-europe/#topicOverview (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Evaluation of formative measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelenchick, L.A.; Eickhoff, J.; Christakis, D.A.; Brown, R.L.; Zhang, C.; Benson, M.; Moreno, M.A. The Problematic and Risky Internet Use Screening Scale (PRIUSS) for adolescents and young adults: Scale development and refinement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanay, G.; Bernstein, A. State Mindfulness Scale (SMS): Development and initial validation. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala, S.; Ramos Campos, F.; Carvalho Relva, I. Emotional Exhaustion Scale (ECE): Psychometric properties in a sample of Portuguese university students. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS GmbH: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Jöreskog, K.G. Interclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 295, pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; de Chernatony, L. Medición del valor de marca: Una propuesta desde un enfoque formativo. In Proceedings of the XXI Congreso Nacional de Marketing, Bilbao, Spain, 16–18 September 2009; ESIC: Bilbao, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.; Kupper, L.L.; Muller, K.E. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Analysis Methods; PWS-Kent Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberg, C.; Schneider, R.; Rumpl, H. Social media addiction: Associations with attachment style, mental distress, and personality. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. From fear of missing out (FoMO) to addictive social media use: The role of social media flow and mindfulness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 150, 107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; DeFleur, M.L. A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas Naqvi, M.H.; Jiang, Y.; Miao, M.; Naqvi, M.H. The effect of social influence, trust, and entertainment value on social media use: Evidence from Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1723825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciantonio, A.; Bourguignon, D. Motivation scale for using social network sites: Comparative study between Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat and LinkedIn. Psychol. Belg. 2023, 63, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.K.; Noh, H.H.; Doh, E.Y.; Rim, H.B. Rejected or ignored?: The effect of social exclusion on Instagram use motivation and behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 3177–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Manchanda, P.; Arora, N.; Aggarwal, A. “I Can’t look at you while talking!”—Fear of missing out and smartphone addiction as predictors of consumer’s phubbing behavior. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varchetta, M.; Fraschetti, A.; Mari, E.; Giannini, A.M. Adicción a redes sociales, Miedo a perderse experiencias (FOMO) y Vulnerabilidad en línea en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct/ Dimension/ Indicator | VIF | Weight | Loading | t-Value | Cronbach Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency (second-order factor) | n.a | n.a | |||||

| Understanding | 1.361 | 0.450 | 0.751 | 0.836 | 0.513 | ||

| SOU1 | 0.816 | 40.048 | |||||

| SOU2 | 0.796 | 32.733 | |||||

| SOU3 | 0.601 | 12.307 | |||||

| SEU2 | 0.645 | 15.234 | |||||

| SEU3 | 0.773 | 23.353 | |||||

| Orientation | 1.491 | 0.712 | 0.758 | 0.838 | 0.503 | ||

| AO1 | 0.666 | 10.832 | |||||

| AO2 | 0.786 | 16.468 | |||||

| AO3 | 0.675 | 10.228 | |||||

| IO1 | 0.712 | 14.906 | |||||

| IO2 | 0.719 | 12.024 | |||||

| IO3 | 0.655 | 11.256 | |||||

| Play | 1.161 | 0.157 | 0.801 | 0.861 | 0.529 | ||

| SP1 | 0.692 | 4.065 | |||||

| SP2 | 0.680 | 3.509 | |||||

| SP3 | 0.725 | 3.862 | |||||

| STP1 | 0.746 | 4.907 | |||||

| STP2 | 0.789 | 5.435 | |||||

| STP3 | 0.702 | 3.962 | |||||

| Addiction (formative) | n.a | n.a | |||||

| ADD1 | 1.539 | 0.311 | |||||

| ADD2 | 1.371 | 0.246 | |||||

| ADD3 | 1.284 | 0.008 | |||||

| ADD4 | 1.513 | 0.107 | |||||

| ADD5 | 1.423 | 0.357 | |||||

| ADD6 | 1.401 | 0.110 | |||||

| ADD7 | 1.220 | 0.428 | |||||

| ADD8 | 1.484 | 0.034 | |||||

| Excessive use (reflective) | 0.745 | 0.855 | 0.663 | ||||

| EUSE1 | 0.777 | 26.754 | |||||

| EUSE2 | 0.802 | 31.366 | |||||

| EUSE3 | 0.861 | 58.986 | |||||

| Instastress (reflective) | 0.701 | 0.867 | 0.765 | ||||

| IST1 | 0.874 | 38.995 | |||||

| IST2 | 0.875 | 46.866 | |||||

| Negative Outcome (reflective) | 0.745 | 0.851 | 0.656 | ||||

| NEGO1 | 0.833 | 18.737 | |||||

| NEGO2 | 0.781 | 13.610 | |||||

| NEGO3 | 0.814 | 19.539 | |||||

| Instagram Mindfulness (reflective) | 0.753 | 0.830 | 0.523 | ||||

| INM1 | 0.601 | 6.544 | |||||

| INM2 | 0.753 | 7.556 | |||||

| INM3 | 0.815 | 34.405 | |||||

| INM4 | 0.829 | 29.659 | |||||

| INM5 | 0.762 | 10.506 | |||||

| Emotional exhaustion (reflective) | 0.767 | 0.855 | 0.603 | ||||

| EE1 | 0.603 | 12.546 | |||||

| EE2 | 0.882 | 52.576 | |||||

| EE3 | 0.903 | 70.932 | |||||

| EE4 | 0.674 | 14.822 |

| Addiction | Mindfulness | Dependency | Emotional Exhaustion | Instastress | Negative Outcomes | Excessive Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction | n.a | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mindfulness | 0.653 | 0.723 | - | 0.713 | 0.242 | 0.530 | 0.625 |

| Dependency | 0.574 | 0.434 | n.a | - | - | - | - |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.700 | 0.556 | 0.499 | 0.776 | 0.354 | 0.529 | 0.744 |

| Instastress | 0.323 | 0.158 | 0.465 | 0.254 | 0.785 | 0,426 | 0.259 |

| Negative outcomes | 0.549 | 0.439 | 0.389 | 0.410 | 0.303 | 0.810 | 0.330 |

| Excessive use | 0.684 | 0.447 | 0.407 | 0.573 | 0.197 | 0.268 | 0.814 |

| Hypothesis | (β) | Weights (Loading) | t-Value (Bootstrap) | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency → addiction | 0.355 *** | 6.123 | Accepted | |

| Dependency → excessive use | 0.407 *** | 8.320 | Accepted | |

| Dependency → Instastress | 0.419 *** | 8.338 | Accepted | |

| Addiction → exhaustion emotion | 0.700 *** | 23.249 | Accepted | |

| Addiction → mindfulness | 0.653 *** | 11.634 | Accepted | |

| Addiction → Instastress | 0.120 * | 2.122 | Accepted | |

| Excessive use → negative outcomes | 0.268 *** | 4.775 | Accepted | |

| Excessive use → mindfulness | 0.025 | 0.005 | Rejected | |

| Excessive use → Instastress | 0.056 | 0.962 | Rejected | |

| Excessive use → addiction | 0.540 *** | 8.944 | Accepted | |

| Formative measures | ||||

| Addiction 1 → Addiction | 0.311 *** | 5.416 | ||

| Addiction 2 → Addiction | 0.246 *** | 5.186 | ||

| Addiction 3 → Addiction | 0.008 | 0.221 | ||

| Addiction 4 → Addiction | 0.107 * | 2.034 | ||

| Addiction 5 → Addiction | 0.357 *** | 6.809 | ||

| Addiction 6 → Addiction | 0.110 * | 2.103 | ||

| Addiction 7 → Addiction | 0.428 *** | 9.350 | ||

| Addiction 8 → Addiction | 0.034 | 0.541 | ||

| Understanding → dependency | 0.450 *** | 5.357 | ||

| Orientation → dependency | 0.712 *** | 9.540 | ||

| Play → dependency | 0.157 *** | 3.543 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrero-Báguena, B.; Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D. When Interaction Becomes Addiction: The Psychological Consequences of Instagram Dependency. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030195

Herrero-Báguena B, Sanz-Blas S, Buzova D. When Interaction Becomes Addiction: The Psychological Consequences of Instagram Dependency. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030195

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrero-Báguena, Blanca, Silvia Sanz-Blas, and Daniela Buzova. 2025. "When Interaction Becomes Addiction: The Psychological Consequences of Instagram Dependency" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030195

APA StyleHerrero-Báguena, B., Sanz-Blas, S., & Buzova, D. (2025). When Interaction Becomes Addiction: The Psychological Consequences of Instagram Dependency. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030195