Configuration Path Analysis of the Virtual Influencer’s Marketing Effectiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Marketing Effectiveness of Virtual Influencers

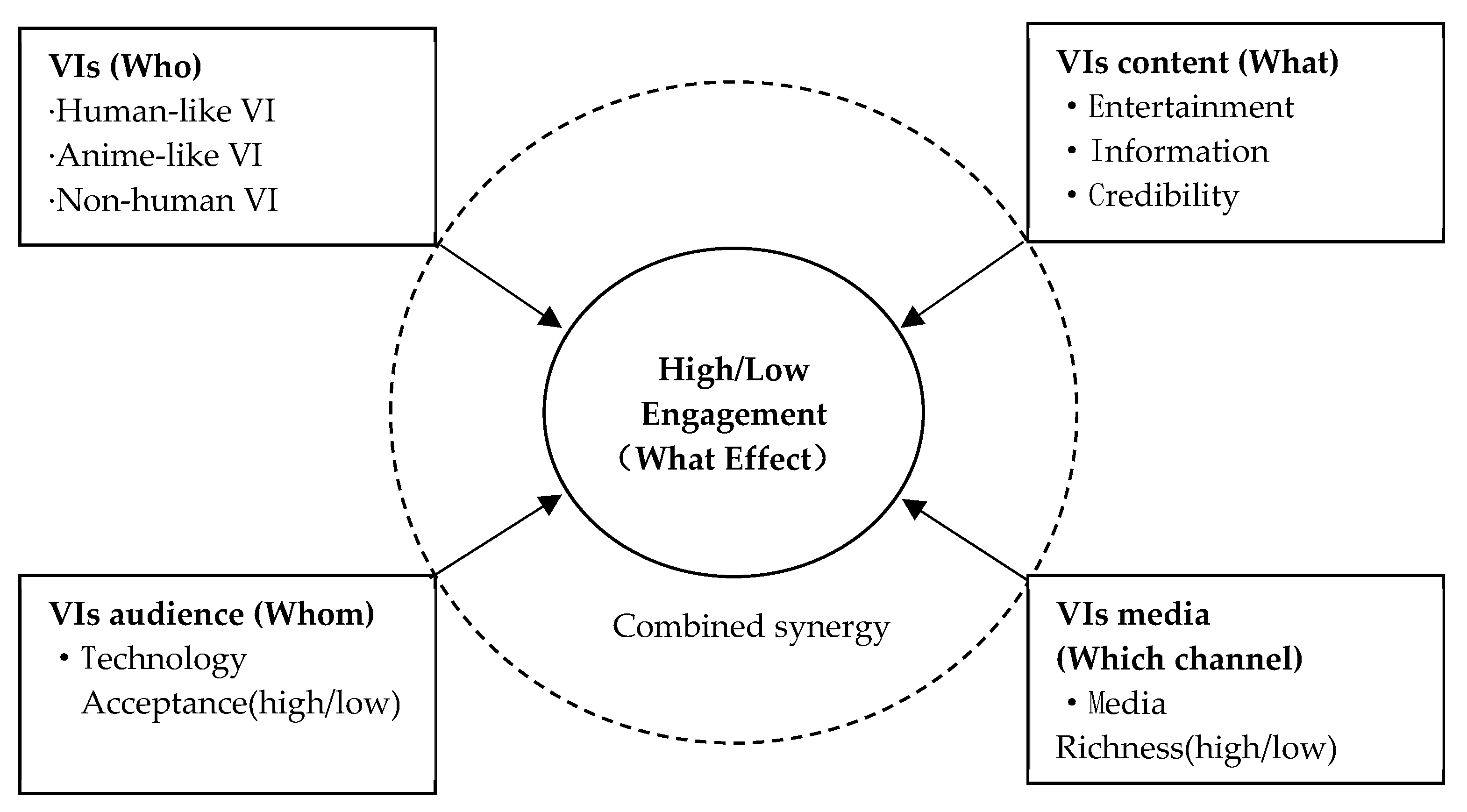

2.2. 5W Communication Model for Virtual Influencers

2.2.1. Communicator Characteristics of Virtual Influencers

2.2.2. Content Characteristics of Virtual Influencers

2.2.3. Media Characteristics of Virtual Influencers

2.2.4. Audience Characteristics of Virtual Influencers

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Calibration and Reliability Test

| Measurement Item | Specific Item | Load | Cronbach’s α | C.R | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VI content characteristics [50,52] | Entertainment | I think the virtual influencer is fun and interesting | 0.784 | 0.781 | 0.704 | 0.877 |

| I found the virtual Influencer to be enjoyable | 0.803 | |||||

| I found the virtual influencer interesting | 0.924 | |||||

| Information | I think the virtual influencer is a good source | 0.880 | 0.815 | 0.733 | 0.891 | |

| I think the virtual influencer is a good channel | 0.828 | |||||

| I think the virtual influencer can provide information | 0.859 | |||||

| Credibility | I trust the influencer | 0.859 | 0.851 | 0.789 | 0.918 | |

| I think the influencer is reliable | 0.882 | |||||

| I find the virtual influencer’s information convincing | 0.924 | |||||

| VI media characteristics (high/low richness) [8] | I can provide and receive timely feedback through the virtual influencer | 0.906 | 0.773 | 0.821 | 0.902 | |

| I can interact with the virtual influencer via text, audio, video, etc. | 0.906 | |||||

| VI audience characteristics (high/low technology acceptance) [61] | I have a favorable attitude towards the virtual influencer | 0.903 | 0.724 | 0.815 | 0.901 | |

| I am receptive to virtual influencers | 0.903 | |||||

| Engagement [8] | I am interested in virtual influencers | 0.930 | 0.825 | 0.768 | 0.908 | |

| I will pay attention to virtual influencers | 0.875 | |||||

| I can communicate and interact with virtual influencers | 0.820 | |||||

3.3. Necessary Condition Analysis

3.4. Conditional Configuration Analysis

3.5. Robustness Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Conclusions

4.2. Theoretical Contributions

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, X.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y. Making Sense? The Sensory-Specific Nature of Virtual Influencer Effectiveness. J. Mark. 2023, 88, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorosrungruang, T.; Ameen, N.; Hackley, C. How Real Is Real Enough? Unveiling the Diverse Power of Generative AI-Enabled Virtual Influencers and the Dynamics of Human Responses. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 3124–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Lei, Y. Mere Copycat? The Effects of Human versus Human-like Virtual Influencers on Brand Endorsement Effectiveness: A Moderated Serial-Mediation Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie-Carson, L.; Benckendorff, P.; Hughes, K. Not so Different after All? A Netnographic Exploration of User Engagement with Non-Human Influencers on Social Media. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Zhou, M. Don’t Like Them but Take What They Said: The Effectiveness of Virtual Influencers in Public Service Announcements. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2269–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Liu, F. From Virtual Voices to Real Impact: Authenticity, Altruism, and Egoism in Social Advocacy by Human and Virtual Influencers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 207, 123650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Lee, D.; Ng, P. The Role of Anthropomorphism and Racial Homophily of Virtual Influencers in Encouraging Low- versus High-Cost pro-Environmental Behaviors. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1833–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. How Technical Features of Virtual Live Shopping Platforms Affect Purchase Intention: Based on the Theory of Interactive Media Effects. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 180, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutuleac, R.; Baima, G.; Rizzo, C.; Bresciani, S. Will Virtual Influencers Overcome the Uncanny Valley? The Moderating Role of Social Cues. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. Understanding the Switching Intention to Virtual Streamers in Live Streaming Commerce: Innovation Resistances, Shopping Motivations and Personalities. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 19, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Qi, G.; Wu, Z.; Sun, H.; Sheng, D. Digital Human Calls You Dear: How Do Customers Respond to Virtual Streamers’ Social-Oriented Language in e-Commerce Livestreaming? A Stereotyping Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Hameed, Z.; Islam, T.; Pant, M.K.; Sharma, A.; Rather, R.A.; Kuzior, A. Avatars of Influence: Understanding How Virtual Influencers Trigger Consumer Engagement on Online Booking Platforms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhov, A.; Friman, M.; Olsson, L.E. Unlocking Potential: An Integrated Approach Using PLS-SEM, NCA, and fsQCA for Informed Decision Making. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.R.; Lee, S.-E. Factors Influencing Engagement in Fashion Brands’ Instagram Posts. Fash. Pract. 2022, 14, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Egger, R. Color and Engagement in Touristic Instagram Pictures: A Machine Learning Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering Consumer–Brand Relationships in Social Media Environments: The Role of Parasocial Interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.B.d.S.; Chimenti, P. “Humanized Robots”: A Proposition of Categories to Understand Virtual Influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 25, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Park, S.; Park, K. Thematic Analysis of Destination Images for Social Media Engagement Marketing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 121, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Silva, M.J.; de Oliveira Ramos Delfino, L.; Alves Cerqueira, K.; de Oliveira Campos, P. Avatar Marketing: A Study on the Engagement and Authenticity of Virtual Influencers on Instagram. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie-Carson, L.; Magor, T.; Benckendorff, P.; Hughes, K. All Hype or the Real Deal? Investigating User Engagement with Virtual Influencers in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, H.D. The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. Commun. Ideas 1948, 37, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Palmatier, R.W. Online Influencer Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Miao, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, L. Standing out or Fitting in? How Perceived Autonomy Affects Virtual Influencer Marketing Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 185, 114917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ran, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, V.L.; Zhou, L.; Wang, C.L. Virtual versus Human: Unraveling Consumer Reactions to Service Failures through Influencer Types. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 178, 114657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. The Effect of Virtual Anchor Appearance on Purchase Intention: A Perceived Warmth and Competence Perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 34, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Teoh, A.P.; Bian, Q.; Liao, J.; Wang, C. Can Virtual Influencers Affect Purchase Intentions in Tourism and Hospitality E-Commerce Live Streaming? An Empirical Study in China. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 37, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dickinger, A.; So, K.K.F.; Egger, R. Artificial Intelligence-Generated Virtual Influencer: Examining the Effects of Emotional Display on User Engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Z. Showing Usage Behavior or Not? The Effect of Virtual Influencers’ Product Usage Behavior on Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Tang, Z.; Liu, D. Can Virtual Streamers Replace Human Streamers? The Interactive Effect of Streamer Type and Product Type on Purchase Intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 43, 0263–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. The Effect of Different Types of Virtual Influencers on Consumers’ Emotional Attachment. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 177, 114646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, Y. Do Virtual Endorsers Have a Country-of-Origin Effect? From the Perspective of Congruent Explanations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, K.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X. Is Virtual Streamer Useful? Effect of Streamer Type on Consumer Brand Forgiveness When Streamers Make Inappropriate Remarks. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tang, Y. Avatar Effect of AI-Enabled Virtual Streamers on Consumer Purchase Intention in e-Commerce Livestreaming. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2999–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. From Human to Virtual: Unmasking Consumer Switching Intentions to Virtual Influencers by an Integrated fsQCA and NCA Method. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Q. The Negative Effect of Virtual Endorsers on Brand Authenticity and Potential Remedies. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 185, 114898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Cheah, I.; Thaichon, P. The Power of Flattery: Enhancing Prosocial Behavior through Virtual Influencers. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1629–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A. The Role of Psychological Distance and Construal Level in Explaining the Effectiveness of Human-like vs. Cartoon-like Virtual Influencers. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 185, 114916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Ki, C.-W.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.-K. Virtual Influencer Marketing: Evaluating the Influence of Virtual Influencers’ Form Realism and Behavioral Realism on Consumer Ambivalence and Marketing Performance. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 176, 114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Zubcevic-Basic, N.; Campbell, C. Diversity in the Digital Age: How Consumers Respond to Diverse Virtual Influencers. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.; Ramadan, Z.; Toth, Z.; Nasr, L.; Karimi, S. Virtual Influencers Versus Real Connections: Exploring the Phenomenon of Virtual Influencers. J. Advert. 2024, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, F.; Stewart, K.; Magalhaes, L. Are They Humans or Are They Robots? The Effect of Virtual Influencer Disclosure on Brand Trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Tong, X. The Effect of E-Commerce Virtual Live Streamer Socialness on Consumers’ Experiential Value: An Empirical Study Based on Chinese E-Commerce Live Streaming Studios. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Ma, F. Human-like Bots Are Not Humans: The Weakness of Sensory Language for Virtual Streamers in Livestream Commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually Human: Anthropomorphism in Virtual Influencer Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. Virtual Influencers’ Attractiveness Effect on Purchase Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model of the Product–Endorser Fit with the Brand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Hao, Y.; Xie, L. Virtual Influencers and Corporate Reputation: From Marketing Game to Empirical Analysis. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 759–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, N.I.; Becker, M.; Reinartz, W. Communicating Brands in Television Advertising. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 57, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Shoenberger, H.; Kim, D.; Thorson, E.; Zihang, E. Novelty vs. Trust in Virtual Influencers: Exploring the Effectiveness of Human-like Virtual Influencers and Anime-like Virtual Influencers. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 44, 453–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the Appeal of User-generated Media: A Uses and Gratification Perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Z.; Rubin, A.M. Predictors of Internet Use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2000, 44, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, L.K.; Carr, B.N. Cyberspace Advertising vs. Other Media: Consumer vs. Mature Student Attitudes. J. Advert. Res. 2001, 41, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, S. Examining the Role of Beliefs and Attitudes in Online Advertising. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Ma, Z.; Chen, T. When and Why Do Consumers Resist Virtual Influencer Endorsement? The Role of Product Depth and Advertising Claim Types. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.R.; He, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Manage. 2006, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia S, Guiret M, Chen A, Tucker M, Gray BE, Vetter C, Garaulet M, Scheer FAJL, Saxena R, Dashti HS. How Accurately Can We Recall the Timing of Food Intake? A Comparison of Food Times from Recall-Based Survey Questions and Daily Food Records. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac002. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.L. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. Soc. FORCES 2010, 88, 1934–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.M.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.H.; Wang, W.J. The Achievement Mechanisms of the Platform Ambidexterity:A Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2017, 20, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y.Z. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in Management and Organization Research: Position, Tactics, and Directions. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 16, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Lou, W.J. Risk Perception of the Public and Acceptance of Emerging Technologies: A Survey Experiment on Facial Recognition Technology. J. Manag. World 2024, 40, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.W.; Lan, H.L. Why Do Chinese Enterprises Completely Acquire Foreign High-Tech Enterprises—A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) Based on 94 Cases. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 4, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jia, L.D. Research on the Driving Pattern of China’s Enterprise Cross-border M&As: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volles, B.K.; Park, J.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Geuens, M. How and When Do Virtual Influencers Positively Affect Consumer Responses to Endorsed Brands? J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183, 114863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Bie, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y. The Effect of Human versus Virtual Influencers: The Roles of Destination Types and Self-Referencing Processes. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Research Context | VI Factors | Content Factors | Media Factors | Follower Factors | Other Factors | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Online survey with social media users | Not studied | Image vs. Video | Not studied | Cultural difference | VI vs. HI | Endorsement effectiveness | Endorsements work better in video format and are influenced by different cultures. |

| [24] | Online survey with social media users | Perceived autonomy | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Product type; VI vs. HI | Purchase intention | Perceived autonomy and purchase intention of virtual influencers are negatively correlated but moderated by product type. |

| [25] | Experiment with Instagram influencers | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Familiarity | VI vs. HI | Forgiveness propensity; Punishment Intention | Consumers had a higher propensity to forgive virtual influencers, but familiarity had no significant effect. |

| [26] | Online survey with social media users | Animal-human-like or all-human-like virtual anchor | Not studied | Not studied | Certainty of needs | Product type | Purchase intention | Animal–human mixing elicits higher purchase intentions, and high (low) certainty needs enhance purchase intentions through enhanced perceptual abilities (warmth). |

| [27] | Survey 416 active viewers of VIs in THCLS | Not studied | Source credibility ofvirtual influencers | Not studied | Not studied | Influencer–product congruence | Purchase intention | Source credibility of virtual influencers positively affects purchase intentions, and influencer–product consistency strengthens the positive effect. |

| [28] | Used 1028 pictures shared by Lil Miquela | Facial action unit | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Influencer–product congruence | Engagement | The findings disclose the significance of happiness, sadness, disgust, and surprise in triggering user engagement when promoting diverse products with visually captivating content. |

| [6] | Online survey with Instagram users | Autonomy | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | VI vs. HI | Digital activism; Altruistic motives | The advantages of virtual influencers in commercial marketing do not necessarily translate to, enhancing their role in, advocacy for social causes. |

| [11] | Online surveys for college students | Human-like vs. animated | Linguistic style | Not studied | Not studied | Product type | Purchase intention | The positive impact of socially oriented language on purchase intentions is reinforced under both experience and search products when virtual anchors are human-like. |

| [29] | Online surveys for college students | Human-like vs. animated VI | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Product usage behavior | Engagement | Virtual influencers demonstrating product use behaviors are more effective at increasing engagement, and human-like is more effective than anime-like. |

| [30] | Online survey with social media users | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Implicit personality | VI vs. HI; product type | Purchase intention | Consumers’ implicit personality variances also influence their willingness to accept virtual streamers. |

| [31] | Online survey with social media users | Mimic-human VI, Animated-human VI, and non-human VI | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Social presence | Emotional attachment; benefit-seeking behavior | Mimic-human VI has lower emotional attachment compared to the other two. |

| [32] | Survey with campus networks, street stops, etc | Country-of-origin; anthropomorphism | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | VE image perception; product value perception | Willingness to pay | Willingness to pay increases significantly when the product and VE country of origin are the same. |

| [33] | Secondary data and situational experiments | Influencer | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | HPVS vs. RHS; brand reputation | Brand forgiveness | When influence is high, virtual anchors receive higher brand forgiveness. |

| [8] | Online survey with VLSP users | Anthropomorphism | Not studied | Media richness | Not studied | Not studied | Purchase intention | Degree of anthropomorphism and media richness positively affect purchase intention. |

| [34] | Online survey | Form realism; behavioral realism | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Relationship norm orientation | Purchase intention | Morphological authenticity and behavioral authenticity interact to influence consumer purchase intention. |

| [10] | Online survey | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Innovation resistance; motivations; personalities | Not studied | Switching intention | Unveiled six configurations of arrangements, each characterized by a unique combination of causation. |

| [35] | Online survey | AI technology-like; human-like; social attributes | Not studied | Not studied | Personalities | Not studied | Switching intention | Unveiled six configurations of arrangements. |

| [36] | Online survey | Aesthetic imperfection | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | multiple brand endorsements; VI vs. HI | Brand authenticity | When endorsers are designed to be aesthetically imperfect, the negative effect of virtual endorsers on brand authenticity is attenuated. |

| [37] | Online survey | Anthropomorphism | Flattery | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Prosocial behavior | When virtual influencers have a highly humanoid appearance, flattery enhances users’ perceptions of their authenticity, which in turn promotes prosocial behavior. |

| [21] | Online survey with Instagram users | Source realness | Image composition and caption discourse | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | Engagement | Humanlike VIs are preferred over 3D animated VIs and the least preferred influencers are 2D animated VIs. Pictures of scenes where the influencer does not exist are most popular. Users preferred rational discourse that provided a travel scenario. |

| [4] | 1112 user comments collected from 52 Instagram posts | Source factors | Content factors | Not studied | Not studied | Source–content factors | Engagement | Users engage with non-human influencers for various reasons, including entertainment value, emotional connection, and educational content. |

| This paper | 205 questionnaires on online platforms | Human-like VI; anime-like VI non-human VI | Entertainment information credibility | Media richness (high/low) | Technology acceptance (high/low) | Different configuration paths | Engagement | Information synergy media richness and technology acceptance influence user participation |

| Name | Options | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 93 | 54.63 |

| Male | 112 | 45.37 | |

| Age | Less than 18 years old | 12 | 5.85 |

| 19–24 years old | 97 | 47.32 | |

| 25–30 years old | 79 | 38.53 | |

| 31–40 years old | 15 | 7.32 | |

| Above 41 years old | 2 | 0.98 | |

| Education | High school and below | 24 | 11.71 |

| Specialized or undergraduate | 135 | 65.85 | |

| Master’s degree and higher | 46 | 22.44 | |

| Income | Less than 2000 yuan | 63 | 30.73 |

| 2001–5000 Yuan | 44 | 21.46 | |

| 5001–8000 Yuan | 40 | 19.51 | |

| 8001–11,000 Yuan | 38 | 18.54 | |

| More than 11,000 Yuan | 20 | 9.76 |

| Conditional Variable | High Engagement | Low Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| VI Communicator | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.42 |

| ~VI Communicator | 0.40 | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| Entertainment | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.20 |

| ~Entertainment | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| Information | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| ~Information | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| Credibility | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 0.18 |

| ~Credibility | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Media Richness | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.19 |

| ~Media Richness | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Technology Acceptability | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 0.21 |

| ~Technology Acceptability | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

| Conditional | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VI Communicator | |||

| Content Characteristics | Entertainment | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Information | ⬤ | ⬤ | |

| Credibility | ⬤ | ⬤ | |

| Media Richness | ● | ||

| Audience Technology Acceptance | ● | ||

| Consistency | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| Raw Coverage | 0.81 | 0.79 | |

| Unique Coverage | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Solution Coverage | 0.84 | ||

| Solution Consistency | 0.98 | ||

| Conditional | Configuration 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| VI Communicator | ||

| Content Characteristics | Entertainment | ⊗ |

| Information | ⊗ | |

| Credibility | ⊗ | |

| Media Richness | ⊗ | |

| Audience Technology Acceptance | ⊗ | |

| Consistency | 0.97 | |

| Raw Coverage | 0.66 | |

| Unique Coverage | 0.66 | |

| Solution Coverage | 0.66 | |

| Solution Consistency | 0.99 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, M.; Hu, H.; Chen, M. Configuration Path Analysis of the Virtual Influencer’s Marketing Effectiveness. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020095

Tian M, Hu H, Chen M. Configuration Path Analysis of the Virtual Influencer’s Marketing Effectiveness. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(2):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020095

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Min, Haiqiang Hu, and Meimei Chen. 2025. "Configuration Path Analysis of the Virtual Influencer’s Marketing Effectiveness" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 2: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020095

APA StyleTian, M., Hu, H., & Chen, M. (2025). Configuration Path Analysis of the Virtual Influencer’s Marketing Effectiveness. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020095