Abstract

The growing use of Instagram and its influencers in marketing demonstrates their substantial influence on customer behavior intentions. Despite this, further research into the effects of Instagram mega-influencers on purchase intention is needed among Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012) consumers. The main aim of the study was to assess the influence of attractiveness, expertise, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness on intention to purchase due to Instagram mega-influencers among Generation Z in South Africa. This study combined purposive and snowball non-probability sampling methods using a quantitative approach. An online questionnaire was used to assess the effect of Instagram mega-influencers on young consumers’ purchase intention, which resulted in 497 Generation Z respondents. Positive associations were found between attractiveness, expertise, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness on intention to purchase. Perceived ease of use was also found to mediate the positive effects of attractiveness and expertise on intention to purchase. This analysis provides businesses with practical information about the use of Instagram mega-influencers in digital marketing to connect with Generation Z consumers and improve profitability. The research contributes to the theoretical development of constructs in the technology acceptance and source credibility models and generation cohort theory.

1. Introduction

The phenomenal elaboration of social media is evident in developing economies, and they are widely used by young customers [1,2,3]. Moreover, the movement of endorsing brands or products through online platform influencers has increased in 2024 [4,5]. It is expected that global brands could spend up to USD 39.3 billion on influencer marketing in 2025 and could show a yearly growth rate of 9.4% to reach USD 56.3 billion by 2029 [6]. Influencer marketing is growing even more rapidly in growing and developing African nations such as South Africa, where brands are expected to spend USD 30.2 million in 2025 and are forecast to yield a yearly growth rate of 10% to reach USD 44.3 million by 2029 [7]. Brands are increasingly using social networking sites to meet their relationship marketing goals and boost their brand value [8]. This shows that traditional advertising media may have become less effective, but it is still relevant [9,10], especially to the older generations, whereas social media (such as Instagram) has become more important to the younger cohort [11,12]. Generation Z is the group of individuals born between 1997 and 2012 who tend to be more receptive to the internet and desire digital interaction [13,14,15]. By 2023, Generation Z represented 27% of worldwide workers and had an estimated purchasing power of in excess of USD 3 trillion [16]. Many recent studies have found that digital influencers have a huge influence on Generation Z’s purchasing decision-making processes and intentions [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Hence, the use of Instagram influencers has evolved into a critical marketing instrument, fundamentally affecting how businesses interact with their audience, particularly among younger demographics. Instagram, with over a billion active users per month, provides a unique platform for brands to increase visibility, stimulate sales, and communicate with potential customers [31,32,33,34]. The rise of Instagram influencers, who exploit their considerable followings to endorse products and services, has become a basis of modern marketing techniques [23,25,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

Campbell and Farrell [43] categorized social media influencers (SMIs) into four distinct classifications according to the number of followers: nano-influencers (<10,000 followers), micro-influencers (10,000–<100,000), macro-influencers (100,000–1,000,000), and mega-influencers (>1,000,000). Mega-influencers generally include traditional celebrities, television and movie stars, well-known personalities, sportspeople, and other public figures, as well as many ordinary people who have made their way to the top of social media fame [44,45]. Mega-influencers can reach worldwide audiences and therefore create global awareness, allow for simple ROI measurements, receive high recognition, and distinguish themselves from other influence categories through their opinion leadership and fame, which leads to favorable sentiment [46]. However, mega-influencers command higher fees and frequently experience lower engagement levels [46]. Dong et al. [19] found that mega-influencers resulted in more favorable purchase intention, engagement, and brand attitudes. Berman et al. [47] found that a mega-influencer on social media with constant content quality supports greater knowledge gathering, whereas lower levels of influencers generate more consumer awareness than a focused advertisement and deliver more revenue. Walter et al. [48] indicated that mega-influencers showed higher levels of general attitudes, engagement, attractiveness, and expertise, whereas lower-level influencers displayed greater similarity, authenticity, and trust. Hence, divergent findings were revealed between various categories of influencers when different constructs, theoretical models, effectiveness, and other variables were examined [19,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. However, the aim of this study was not to compare different categories of influencers. The focus was to assess one category (viz., mega-influencers) using variables from the technology acceptance model (TAM) and source credibility model (SCM). However, the aforementioned authors suggest the need for further research on different categories of influencers, which include mega-influencers [19,46,47,48,49,50,51,53].

Farrell et al. [54] and Pradhan et al. [55] propose that Instagram has created new opportunities for influencers and is considered an effective conduit to shape consumers’ behaviors. Many studies have been conducted in developed countries [39,45,48,50,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] and developing countries [19,20,25,35,66,67,68,69], which analyzed the effect of Instagram influencers and other forms of SMIs on young consumers, but further studies in developing countries are proposed especially due to the persistent growth of this relatively new form of marketing. Research demonstrates the necessity of more studies comparing the purchasing intentions of Generation Z customers in various countries [23,27,60,70,71,72,73,74]. For quantitative studies on Generation Z, global research highlights the significance of larger samples and a more diversified population [27,65,75,76,77]. Chumley [78] and Sandra et al. [79] examined the impact of using Instagram influencer marketing on customers’ purchase intent, but these studies and others also noted that further study was needed to confirm the effects of marketers’ usage of social media in a broader communication environment [80,81]. Several TAM variables, for example, perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceived usefulness (PU), were used to examine various aspects of digital influencer marketing [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. However, there is a research gap to broaden the TAM, especially when combined with variables from the SCM, for example, attractiveness and expertise, which are frequently used in SMI and Instagram influencer studies [20,65,66,90,91,92,93,94].

The study makes a contribution to the sustainable development goal (SDG) 8 (decent work and economic growth) and endeavors to show that different types and new forms of social media marketing can assist to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” to reach younger cohorts and therefore improve the profitability and growth of various forms of organizations in South Africa [95,96,97,98]. Hence, to bridge the aforementioned research gaps, the main aim of the study is to examine the effect of attractiveness, expertise, PU, and PEU on intention to purchase, as well as the mediating role of PU and PEU, due to Instagram mega-influencers among Generation Z in a developing African country such as South Africa.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Models

To establish the relationship between Instagram mega-influencers and Generation Z’s purchasing intention, the current study employed the TAM and SCM. Davis [99] developed the TAM, which researchers use to assess how effectively customers accept new technologies [100,101,102]. The TAM variables adopted in this study include PU, PEU, and behavioral intentions (i.e., intention to purchase) [99,103,104,105,106,107]. The TAM has been revised by several studies to examine various forms of digital influencer marketing [83,84,85,87,88,89], but further inquiry is needed, especially among young cohorts in developing countries. Sethi and Kapoor [93], Akin, [86], Gonçalves et al. [87], and Khan et al. [88] suggest that it is essential to comprehend relationships between SMIs and Instagram influencers and consumer use behaviors, particularly those of young people, in order to provide insight into successful interaction and potential policies that might control social media marketing. Thus, in this context of Instagram mega-influencers, this research investigates young consumers’ evaluations of the platform based on how user-friendly it is and how effectively it assists corporations to achieve their marketing objectives via Instagram mega-influencers in terms of Generation Z’s purchase intention.

Ohanian [108] defined source credibility as a term that refers to the communicator’s positive attributes that influence the receiver’s acceptance of a message. The source credibility model asserts that the endorser’s perceived level of attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness determines the effectiveness of a message. Pereira et al. [60], Kim and Yoon [109], and Najar et al. [110] showed that the SCM is constructed through attractiveness, expertise, and trustworthiness to evaluate the features that enhance the receiver’s attitude and purchasing intentions concerning the products. Flores-Zamora [111] and Zhang et al. [112] mention the inclusion of attractiveness, which suggests that a physically appealing communicator is liked more and has a favorable impact on attitude change and product appraisal. Garg and Bakshi [93], Behnoosh et al. [113], and Lajnef et al. [114] note that influencer experience signifies the extent to which the audience believes they possess advanced abilities or expertise in a specific profession, which makes it easier for audiences to trust influencers on social media platforms [109,110]. Several other investigations agreed with the aforementioned studies in that credibility attributes (e.g., attractiveness and expertise) of SMIs (including Instagram influencers) are seen to have a substantial impact on one’s assessment of information believability and purchase intention [20,66,90,91,92,93,94,115,116]. This study did not examine trust, which is consistent with prior recent influencer investigations that similarly excluded this variable from their models, which instead focused on other aspects of source credibility [20,117,118]. Therefore, this study also considers SCM variables, which include attractiveness and expertise, in relation to the aforementioned TAM variables (PU and PEU) to assess their impact on intention to purchase from Instagram mega-influencers among Generation Z consumers.

2.2. Hypotheses

Attractiveness is associated with physical attributes, such as similarity, likeability, and familiarity, which are important for compliments or judgments about a person [119,120,121]. Generally, people value attractiveness among their characteristics. The physical attractiveness of SMIs is observed to have a high tendency to monitor the average acceptance of advertising [122,123]. Several researchers proposed a favorable impact of the attractiveness of SMIs on consumer behavioral or purchase decisions [60,61,65,66,92,93,124,125,126,127,128,129]. However, other studies suggest that celebrity traits are not essential for intention to purchase [130,131,132]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H1.

The attractiveness of Instagram mega-influencers has a positive influence on intention to purchase.

Expertise denotes a considerable degree of knowledge, ability, and competency that an individual or organization possesses in a particular field of knowledge [133,134,135]. Influencer expertise is frequently identified by demonstrated proficiency and experience, which enables authorities to complete activities or make opinions with high accuracy and effectiveness [136,137,138]. Previous research has found that target groups’ purchase intention is higher when influencers have more experience, hence positing that Instagram and other forms of digital influencers’ expertise favorably affect behavioral/consumer purchase intention [41,60,61,62,65,66,92,93,124,139]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H2.

The expertise of Instagram mega-influencers has a positive effect on intention to purchase.

Perceived usefulness refers to the extent to which technology is perceived to enhance productivity and efficiency [99]. Ajibade and Zaidi [140] and Balouchi and Aziz [141] underline that this concept is strongly related to the simplicity of social networking sites, which allows users to achieve their objectives more efficiently. The behavioral/purchase intention of Millennials and Generation Z was found to be influenced by perceived usefulness in research on several digital and social media platforms, which included Instagram [142,143,144,145,146]. Several studies revealed that perceived usefulness was an important factor influencing how digital influencers affect young consumers’ behavioral/purchasing intentions [84,88,93,127,147]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H3.

The perceived usefulness of Instagram mega-influencers has a favorable effect on intention to purchase.

Perceived ease of use is a measure of how much a user expects a certain technology to be simple to use [99,103]. A user’s view of the time and effort required to make a purchase by clicking on Instagram’s purchase buttons may differ [148,149]. Perceived ease of use was found to have a positive influence on behavioral and purchase intention on social media and other digital platforms [143,145,150]. Fauzi et al. [84], Khan et al. [88], and Bil et al. [151] also showed that perceived ease of use was a significant element that impacted purchasing/behavioral intentions among young consumers through digital influencers. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H4.

The perceived ease of use related to Instagram mega-influencers has a significant effect on intention to purchase.

The attractiveness of SMIs or Instagram influencers and the perceived usefulness of Instagram are significant factors influencing consumers’ purchase or behavioral intentions. For example, studies indicate that physical attractiveness amplifies the attractiveness and credibility of an influencer, thus improving consumer receptiveness to their opinions [128,129]. Concurrently, the perceived utility of the application assures that customers gain value from the platform, thereby promoting engagement [143,144,145,150]. Many other studies in the fields of digital and social media marketing and influencers have found similar associations between source attractiveness and/or perceived usefulness and behavioral/purchase intention [41,45,61,89,93,116,127,128,132,142,152,153,154,155]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H5.

Perceived usefulness mediates the effect of the attractiveness of Instagram mega-influencers on intention to purchase.

Several studies have consistently found that the expertise (experience) and/or perceived usefulness of SMIs (and other social media channels) influence purchase/behavioral intention [89,124,142]. Digital and social media platform messages and/or influencers’ (including Instagram) expertise improve credibility, ensuring their recommendations are more valuable and trustworthy to consumers, which could increase perceived usefulness [88,155,156]. As a result, there is a higher probability that customers will act on these recommendations, which increases their purchase intention [45,61,83,88,93,115,127,145,147,152]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H6.

Perceived usefulness mediates the effect of the expertise of Instagram mega-influencers on intention to purchase.

A number of inquiries highlighted the importance of influencer attractiveness and/or perceived ease of use in modifying consumers’ purchase/behavioral intentions [84,88,124,125,128,151]. Influencer attractiveness has been demonstrated to capture attention, which resulted in increased purchase intention [126,127,129]. Furthermore, attractive influencers make substances appear more user-friendly through entertaining demos, which could enhance perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions [88,118,157]. Additionally, several other social media marketing/influencer-related inquiries affirm that attractiveness and/or perceived ease of use and behavioral/intention to purchase result in varied relationships [41,45,61,89,93,143,153]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H7.

Perceived ease of use mediates the effect of the attractiveness of Instagram mega-influencers on intention to purchase.

Previous research revealed that the expertise (experience) and/or perceived ease of use of SMIs and social media platforms have an impact on behavioral or purchase intention [89,142]. Herzallah et al. [142] examined the components that influence Instagram purchases and encourage the expansion of Instagram commerce. The results show that the experience or expertise, attitude, perceived ease of use, and alternative opinions regarding the influencers have an impact on customers’ purchase intention. Qiu et al. [89] examined the effect of short-form video platforms using the TAM and SCM for SMIs to consider behavioral intentions toward travel destinations. The expertise of SMIs in the short-form video platforms showed positive attitudes, which resulted in favorable behavioral intentions toward travel destinations. However, perceived ease of use did not have a significant influence on the attitudes or behavioral intentions toward travel destinations. Other social media and/or SMI-related research also suggested varying relationships in terms of expertise and/or perceived ease of usefulness, which could elevate behavioral/purchase intention [41,45,61,88,115,116,124]. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H8.

Perceived ease of use mediates the effect of the expertise of Instagram mega-influencers on intention to purchase.

3. Materials and Methods

The research adopted the post-positivist paradigm to objectively assess the hypothesis via a structured and deductive approach. Hence, the research employs a quantitative approach because the search involves gathering and generalizing numerical data from a group of people. Hence, the aim of the study is to measure the behavior of Generation Z consumers due to their exposure to Instagram mega-influencers. A descriptive research design was used to investigate relationships between Instagram mega-influencer TAM and SCM measures and, therefore, validate the drivers of Instagram mega-influencers’ intentions to purchase among Generation Z consumers.

The research population in this study consists of members of Generation Z aged between 16 and 27 years old in South Africa who follow Instagram mega-influencers. Consequently, it is thought that purposive sampling, also referred to as judgmental sampling, is suitable for identifying participants who may respond to the study’s research objectives. The initial sampling process emphasizes the Generation Z cohort, specifically individuals who use Instagram and who follow mega-influencers at several universities. Thereafter, the snowball approach was used in the second step of sampling. A Google Forms link was forwarded by the initial respondents to their contacts via WhatsApp and social media to reach young working adults and a diverse range of communities across the developing African country, which produced 497 Generation Z respondents.

An online questionnaire was used to evaluate the impact of Instagram mega-influencers on Generation Z consumers’ purchase intention. The self-administered survey used screening questions to confirm the use of Instagram and mega-influencer followership, and information from demographic questions relating to gender, age, and education was gathered. Table 1 provides a summative overview of the demographic variables.

Table 1.

Demographic variable frequencies.

The third section used a five-point Likert scale to assess respondents’ SCM and TAM attitude measures to Instagram mega-influencers based on various studies, including attractiveness [158,159], expertise [160,161], perceived ease of use [96], perceived usefulness [103], and intention to purchase [162,163,164,165]. Table 2 shows an outline of the individual Likert scale measures.

Table 2.

SCM and TAM attitude measures (factor loadings, AVE, CR, and Cronbach’s α).

The complex nature of the methodological aspect of the research resulted in a rigorous analysis of the hypotheses in terms of reliability, validity, and robust statistical analysis techniques to ensure accurate interpretation of the findings. Hence, the data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 30 software to generate descriptive statistics and statistical modeling, as well as to assess the data’s reliability via composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha (α). The factor loadings (FLs) and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess convergent validity. Fornell and Larker’s [166] correlation matrix formula and Henseler et al.’s [167] heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio measures were used to assess the discriminant validity. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the validity as well as verify the construct items. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses via AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) software. The Results Section comprehensively presents and discusses the execution of the statistical analysis (refer to Table 2). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure was employed to evaluate the sample adequacy and correlation matrix factorability, which was examined using Bartlett’s Sphericity (BS) measure. Q-Q plots and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) measures were adopted to assess the distribution of the data, with Cook’s Distance (CD) measure to detect and remove outliers, hence enhancing data distribution normality [168].

The study obtained ethical clearance from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Faculty Research Ethics Committee (FREC) (FBMSREC0722021). All participants were assured confidentiality and privacy and could withdraw from the study at any time. This study was conducted in a manner such that all participants thoroughly comprehended the study’s background, the nature of the investigation, and the research purposes, as well as the techniques described in the FREC ethical informed consent form. For example, all participants had the option of not answering any of the questions if they did not feel comfortable completing the questionnaire. The respondents were surveyed, and it was determined that there were no ethical challenges in the study.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

The KMO measure indicated noteworthy sample adequacy with a result of 0.936. The correlation matrix’s factorability, using BS measures, also yielded satisfactory results at p < 0.001. The KS measures yielded significant results (p < 0.001) for the five components, indicating a non-normal distribution of data, which is typical for larger sample sizes [168]. Nonetheless, an examination of the Q-Q plots indicated somewhat linear patterns, implying that the distribution of data was normal. The CD measure test was employed to identify outlier Generation Z attitudinal answers, but no responses were eliminated since the distribution was normal [168].

The CR and Cronbach’s α measures were used to confirm the constructs’ reliability. The CR measures in this sample ranged from 0.834 to 0.902, signifying substantial internal consistency, and Cronbach’s α measures ranged from 0.748 to 0.885, displaying satisfactory reliability coefficients above 0.7 (refer to Table 2). FLs and AVE were used to evaluate the convergent validity of the SCM and TAM attitude measures. The FL rates ranged from 0.673 to 0.897, and the AVE rates ranged from 0.629 to 0.698, which supported the validity of convergent validity since all measures were more than 0.5 (see Table 2).

The square root of the AVE for each Instagram mega-influencer SCM and TAM attitude measure, which needs to be greater than the correlations between the measures, was used to evaluate discriminant validity. Since the square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than its correlations, it shows that discriminant validity is present [166], as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

The HTMT ratio was further utilized to evaluate the discriminant validity of the Instagram mega-influencer SCM and TAM attitude measures. The HTMT ratios were within the permitted threshold of 0.85 [167], as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

HTMT ratio measures.

The hypothesized Instagram mega-influencer SCM and TAM attitude measure relationships were evaluated via SEM analysis. The SEM analysis goodness-of-fit measures for this study indicated a satisfactory SEM model fit, which was assessed via several model-fit measure thresholds: χ2/df = 1.688; NFI = 0.954; GFI = 0.954; CFI = 0.981; NNFI = 0.976; RMSEA = 0.037; and SRMR = 0.037.

An assessment of common method bias was used to examine the unconstrained–constrained common method factor models. The χ2 measure was significant at p < 0.001, thereby indicating significant shared variance between the unconstrained–constrained common method factor (CMF) model. Thus, it was necessary to impute the inferred unconstrained CMF model, which was utilized for further statistical analysis in this study. The SEM analysis goodness-of-fit measures for the unconstrained CMF model also produced an excellent SEM model fit: χ2/df = 1.255; NFI = 0.971; GFI = 0.970; CFI = 0.994; NNFI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.023; and SRMR = 0.022. The mediation analysis applied bootstrapping with 5000 resamples at a level of confidence of 95%.

The SCM and TAM attitude measures for Instagram mega-influencers were checked through multicollinearity tests, which were used to examine the components to check that they were not exceedingly correlated, as this might result in a negative influence on the coefficient’s reliability. The Instagram mega-influencer SCM and TAM attitude measure tolerances varied from 0.552 to 0.651 (<0.1), and the variation inflation factors (VIFs) varied from 1.536 to 1.813 (>5), which reveals that these measures were not exceedingly correlated [168] (refer to Table 5).

Table 5.

Tolerance and VIF measures.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

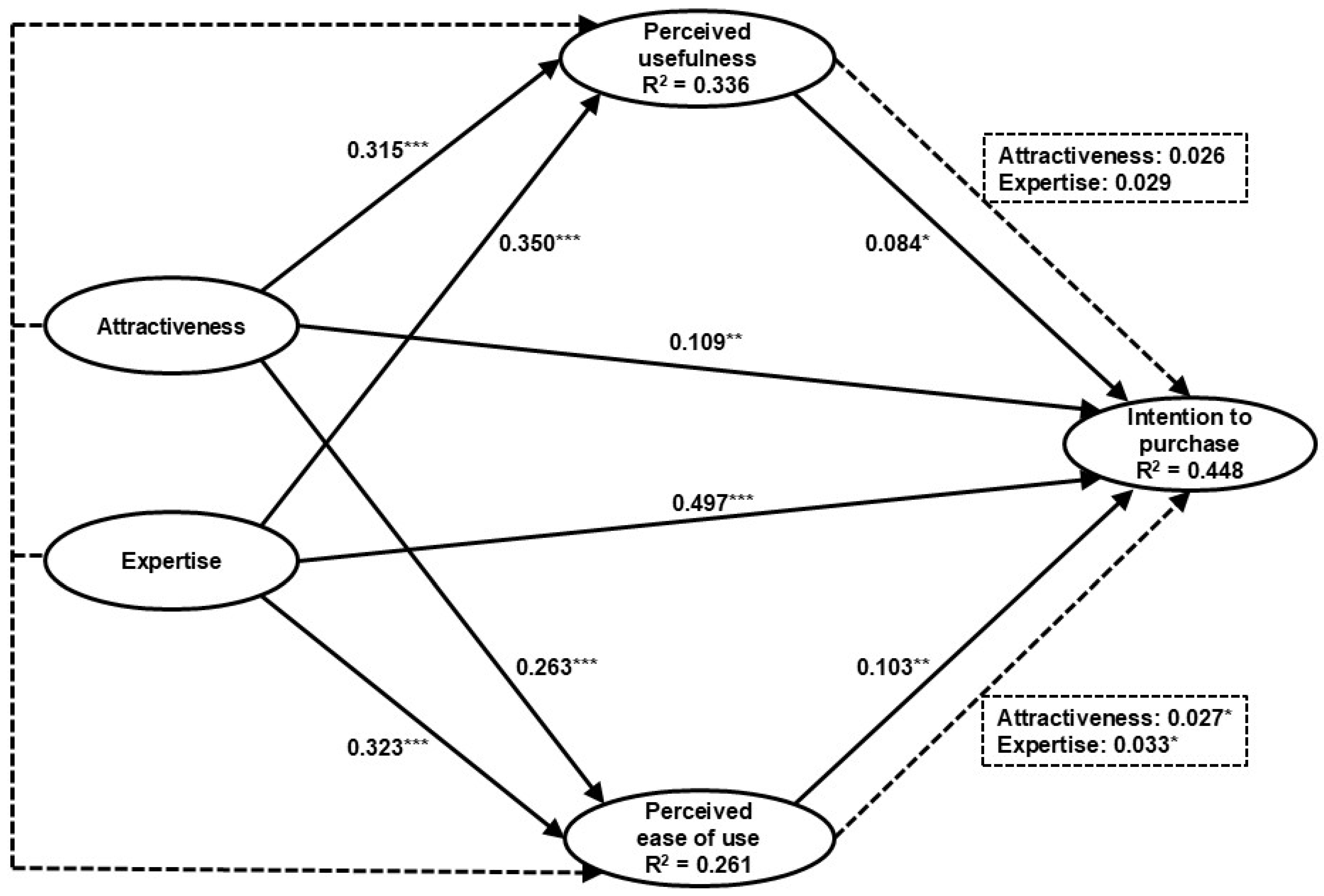

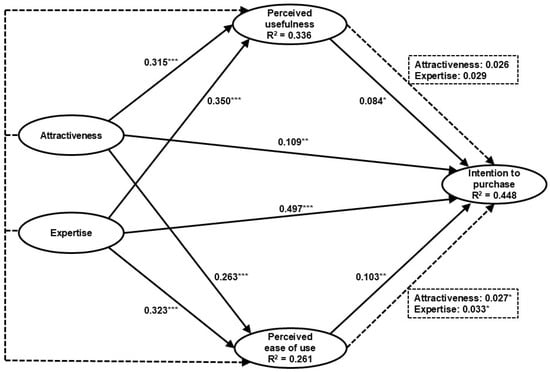

The SEM was used to examine the hypothesized SCM and TAM attitudinal measure relationships between Instagram mega-influencers. Attractiveness and expertise explained 36.6% of the perceived usefulness variance; attractiveness and expertise explained 26.1% of the perceived ease of use variance; and attractiveness, expertise, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use explained 44.8% of the intention to purchase variance. The variance, standardized beta (β) coefficients, and significance levels are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Standardized β coefficients. Notes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05. Source: computed by the authors.

The attractiveness → intention to purchase (β = 0.109, t = 2.593, p < 0.01) and expertise → intention to purchase (β = 0.497, t = 11.517, p < 0.001) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations; therefore, H1 and H2 were supported. The perceived usefulness → intention to purchase (β = 0.084, t = 2.057, p < 0.05) and perceived ease of use → intention to purchase (β = 0.103, t = 2.654, p < 0.01) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations; therefore, H3 and H4 were supported.

The attractiveness → perceived usefulness (β = 0.315, t = 7.391, p < 0.001) and the attractiveness and intention to purchase (as per H1 above) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations. However, perceived usefulness was not found to mediate the positive effect of attractiveness on intention to purchase (β = 0.026, LL = 0.003, UL = 0.058, p = 0.066); therefore, H5 was rejected.

The expertise → perceived usefulness (β = 0.350, t = 8.202, p < 0.001) and the expertise and intention to purchase (as per H2 above) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations. However, perceived usefulness was not found to mediate the positive effect of expertise on intention to purchase (β = 0.029, LL = 0.003, UL = 0.062, p = 0.067); therefore, H6 was rejected.

The attractiveness → perceived ease of use (β = 0.263, t = 5.840, p < 0.001) and the attractiveness and intention to purchase (as per H1 above) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations. Furthermore, perceived ease of use was also found to mediate the positive effect of attractiveness on intention to purchase (β = 0.027, LL = 0.007, UL = 0.052, p < 0.05); therefore, H7 was supported.

The expertise → perceived ease of use (β = 0.323, t = 7.164, p < 0.001) and the expertise and intention to purchase (as per H2 above) standardized path β coefficients produced significant positive associations. Furthermore, perceived ease of use was found to mediate the positive effect of expertise on intention to purchase (β = 0.033, LL = 0.009, UL = 0.064, p < 0.05); therefore, H8 was supported.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study showed that young customers’ purchasing intentions were positively impacted by Instagram mega-influencers possessing attractive features. A number of other inquiries indicate that SMIs and/or Instagram influencers’ physical attractiveness has a strong tendency to increase purchase/behavioral intentions due to this form of marketing [60,65,92,93,125,128]. Several studies highlight that using attractive digital influencers to influence Generation Z’s purchase intention toward a business is an effective strategy [61,66,124,127,129]. Hence, young consumers are more inclined to purchase from a brand that is sponsored by an attractive Instagram mega-influencer because they are more likely to be viewed as credible while promoting a product, which may affect the consumers’ propensity to purchase. The researchers agree that mega-influencers’ appearance and commercial disclosure are crucial aspects in influencer marketing due to the brand awareness created by influencers’ attractiveness, which is further enhanced by visible advertising disclosure and influences buyer intentions.

This study demonstrated that Instagram mega-influencers had a favorable impact on the association between the correlation between expertise and intention to purchase among Generation Z consumers. Influencers are frequently regarded as authoritative, and the legitimacy of the information they give is greatly influenced by their knowledge and experience [60,62,66,124,139]. Generation Z consumers are more likely to accept their advice and recommendations from Instagram and other forms of digital influencers, which encourages favorable behavioral views of the recommended brands and products [41,61,65,92,93]. The significance of the influencer’s expert knowledge is further reinforced by their capacity to communicate difficult information in an understandable way [38]. Hence, followers are persuaded to consider mega-influencer recommendations by a compelling narrative created by the trust generated by the perceived competence of endorsed brands. Instagram mega-influencers’ expertise thus becomes a crucial component in the complex dynamics of young customers’ choices in the context of influencer marketing.

The study showed that the use of Instagram mega-influencers for digital marketing with young consumers led to a favorable association between perceived usefulness and purchase intention. Akin [86] and Pham et al. [152] confirm that perceived usefulness is an important element influencing young consumers’ propensity to make online purchases through SMIs. Multiple investigations have confirmed that perceived usefulness significantly influences the impact of Instagram and other forms of digital influencers on the behavioral or buying decisions predominantly among younger cohorts [83,84,88,127,147]. The study results imply that when businesses work with Instagram mega-influencers, it becomes simpler to elicit positive consumer purchase intentions, which in turn fosters a favorable association. It is therefore advisable that marketers take into account this strategy of usefulness in order to develop Instagram marketing campaigns that connect with their target audience and heighten the propensity of customers to make a purchase due to the perceived usefulness of mega-influencers. Therefore, businesses should take into consideration that perceived usefulness can play a significant role when developing social media strategies to influence consumers’ intentions of purchasing products via the use of Instagram mega-influencers as a way to enhance their profitability.

The study revealed that Instagram mega-influencers in digital marketing resulted in a positive relationship in terms of perceived ease of use and intention to purchase. Lopez [143], Xie et al. [145], and Madi et al. [150] also revealed a positive relationship between perceived ease of use and purchase intentions on various social media and digital conduits. The current research, therefore, posits that companies promoted by Instagram influencers made it easier for customers to use them, which has a positive effect on purchase intention in social media. Other digital influencer inquiries verified that purchasing/behavioral intentions were enhanced by the perceived ease of use among young customers [84,88,151]. Therefore, it can be surmised that mega-influencers who are known to positively affect Gen Z’s perceptions based on their ease of use are able to effectively persuade, motivate, and influence a wide range of young consumer audiences across multiple countries and digital platforms, which cannot be achieved via traditional marketing techniques. Hence, marketers must comprehend the inclinations and simplest ways to reach Generation Z consumers as their influence in the marketplace grows, which could be effectively achieved via Instagram mega-influencers.

The study did not show statistically significant mediation relationships regarding Instagram mega-influencers’ attractiveness and perceived usefulness, as well as expertise and perceived usefulness, toward intention to purchase. However, this investigation is different from other digital influencers and social media marketing studies, which found various positive associations between source attractiveness, expertise, perceived usefulness, and/or behavioral/purchase intention [45,61,93,127,152]. The aforementioned inquiries did not specifically consider Generation Z and/or Instagram mega-influencers in the context of a developing African country, which could have resulted in different findings. Attractive influencers regularly have a large number of followers since they are viewed as credible and as having expertise, which increases their power to influence purchasing decisions, especially among young consumers. An influencer’s endorsement gains credibility according to their expertise, and from the consumer’s point of view, a brand’s perceived usefulness offers concrete value. In order to effectively influence consumers’ purchasing intentions, brands should strategically cooperate with influencers who have expertise in the brand.

The study revealed Instagram mega-influencers generated a favorable mediation relationship regarding attractiveness and perceived ease of use toward purchasing intentions. An appealing influencer incorporates a product into Generation Z’s everyday routine and raises the brand’s perceived ease of use by making it approachable and intuitive [88,118,157]. Consumer views are further influenced, and a desire to purchase the recommended brand is cultivated due to the influencer’s charisma and visual appeal, which add to the overall attractiveness of the product [41,45,61,93]. An Instagram mega-influencer’s general appeal and charm are included in their attractiveness, which extends beyond their physical appearance. An attractive mega-influencer has the power to effectively captivate and engage an audience, forging an emotional bond with the brands they support. As a result, the connection between perceived ease of use and Instagram mega-influencers’ attractiveness forges a compelling association that draws in young consumers and enhances their purchase intentions.

The study yielded a significant positive relationship between the perception of ease of use, which is influenced by Instagram mega-influencer expertise, and intention to purchase among Gen Z consumers. The above findings are consistent with previous research by Bastrygina et al. [41], Bratina and Faganel [61], Khan et al. [88], Ata et al. [115], and Ooi et al. [116], which suggests a positive association between Instagram and/or SMIs’ expertise and/or perceived ease of use in various marketing contexts and could increase behavioral/purchase intentions among young consumers. Marketing communications gain credibility and authority from Instagram mega-influencers, which increases their persuasiveness and consumer trust. Mega-influencers who are seen as experts in their field are more likely to have audiences that connect with their endorsements, which raises the perceived value of the brands they suggest. Therefore, it can be surmised that Instagram mega-influencer expertise influences Generation Z consumers’ intention to buy by enhancing their favorable impression of digital marketing’s ease of use. These results highlight how important it is for marketers hoping to create effective marketing strategies to comprehend Generation Z preferences and communication styles.

6. Conclusions

From a theoretical implication viewpoint, the investigation expands on recent TAM [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] and SCM [20,65,66,90,91,92,93,94] research by examining whether young consumers consider Instagram mega-influencers used in digital marketing campaigns as a technique that influences their purchase decisions. Although this study makes a contribution regarding the use of Instagram mega-influencers in digital marketing, there was a need for further inquiry concerning the way SMIs impact younger consumers’ perceptions when used in digital marketing [18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. This is because, in contrast to the traditional TAM and SCM, this study integrated attractiveness, expertise, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and intention to purchase when considering Instagram mega-influencer utilization in digital marketing communications among the Generation Z cohort.

From a practical or managerial implication viewpoint, Instagram mega-influencers were found to be important to digital media marketing because they create compelling appeals that motivate young consumers to purchase, particularly via social media content and personal interactions, which can improve business profitability. Attractive mega-influencers have huge followings and are perceived as more reputable and trustworthy by their audience, increasing their ability to influence purchasing decisions. Moreover, sometimes brands that are promoted by influencers who are perceived as unattractive might not increase consumer buying intentions. Therefore, marketers are advised to use attractive mega-influencers because they greatly improve the efficacy of marketing messages by drawing users’ attention as they scroll through their feeds, which may increase the possibility that users can retain the message and enhance purchase intent. Therefore, it is crucial to leverage Instagram mega-influencers for endorsements in a manner that is genuine and appealing to the young target audiences. An influencer’s expert knowledge is crucial for building authority and credibility in a certain field or business. Hence, Instagram mega-influencers’ recommendations have a greater chance of being accepted by their young audience when they exhibit in-depth expertise and understanding. Customers are more likely to think that a knowledgeable mega-influencer’s suggestions suit their requirements and tastes, which helps to create favorable behavioral impressions of the products that are recommended. Thus, marketers should strategically harness and demonstrate mega-influencer expertise by acknowledging its impact on consumer views and purchase decisions to improve profitability. In addition, Instagram mega-influencers have the exceptional capacity to present a product in authentic environments, giving prospective young buyers a sound understanding of its usefulness and worth. Hence, the use of Instagram mega-influencers provides businesses with a powerful means of navigating the competitive environment, connecting with their target audience, and therefore producing more effective marketing strategies. The perception of a product or service can be greatly impacted by suggestions from Instagram mega-influencers who are frequently regarded as reliable and trustworthy, which increases their perceived usefulness among young audiences. Influencer content’s relatability and authenticity increase its perceived usefulness, which is a key component in influencing customer behavior. Marketers should proactively coordinate their marketing efforts with mega-influencers to generate positive views by realizing the symbiotic relationship between perceived usefulness and purchase intention. Instagram mega-influencers are frequently seen by consumers as approachable and user-friendly, and this sentiment is transferred to products that they endorse and influences how consumers make purchase decisions. Marketers are advised to align with Instagram mega-influencers who can effectively convey the simplicity and convenience of their products or services, especially by reinforcing their perceived ease of usefulness to enhance behavioral intentions. Furthermore, perceived ease of use is a crucial distinction that marketers may leverage to shape consumers’ intention to purchase by influencing their confidence in their ability to utilize and benefit from a product. Therefore, it is strategically essential for businesses aiming to improve their brand image and increase customer conversions to utilize Instagram mega-influencers.

The study highlights some important factors that marketers should consider when focusing on Generation Z customers via SMIs to increase their propensity to make purchases. Marketers could leverage Instagram mega-influencers to simplify and interpret their brands, making them more social and accessible, when integrating them into their digital marketing campaigns. Thus, by using this strategy, brands can modify their products and services and benefit from Instagram mega-influencers’ attractiveness, expertise, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use to spread awareness, increase productivity, and provide relevant content. As a result of their perception as approachable, reliable, authoritative, and trustworthy opinion leaders, Instagram mega-influencers help humanize businesses and strengthen their relationship with younger consumers. Hence, Generation Z consumers are attracted to brands that interact with Instagram mega-influencers and solicit feedback, as this may positively influence their purchase intention. Instagram mega-influencers can potentially enhance business income and profitability through creative and engaging interactions; therefore, marketers should actively manage them to receive comments, shares, and responses to their content. Therefore, to select suitable Instagram mega-influencers and develop campaigns that engage young target audiences and positively influence purchase intention, it is essential to understand how Generation Z customers interact with, seek information from, and make product purchases online. The study shows that using Instagram mega-influencers has a beneficial impact, enabling marketers to increase their sustainable marketing practices and efficacy and cultivate a positive mindset among young digital media users.

In conclusion, this study contributes tremendously to the understanding of the extended TAM and SCM and the use of Instagram mega-influencers in digital marketing in a developing country. The study also has important theoretical and practical implications, and it could help Generation Z customers make more favorable purchases by using influencers as a marketing technique. This study is significant as it will ensure that customer preferences are better understood as they are altered by emerging technology. It will also provide a platform to improve the efficacy of marketing strategies, helping brands, corporations, marketers, and advertisers become more competitive in the market. Digital marketing will constantly need to be improved because the world is in a state of continual flux and becoming more digital on a daily basis as young generational preferences are changing. Furthermore, using Instagram mega-influencers for marketing helps realize SDG 8, since this form of social media marketing strategy effectively targets younger audiences, which can improve the profitability and growth of organizations in developing African countries.

The study is not without limitations, which creates avenues for additional inquiry. First, the research was cross-sectional, so it is plausible that variations in consumer attitudinal responses might differ with time, which could be further limited by the selection of viable responses. Researchers may investigate a broader variety of factors that can affect young consumers’ impressions of the use of Instagram mega-influencers, and a qualitative study could be performed to enable respondents to participate more fully. Second, the sample was selected using a non-probability sampling method, which combined purposive and snowball techniques. Further research might consider using probability sampling methods (e.g., stratified or simple random sampling), increasing the sample size, and using a more representative sampling frame in a bid to enhance the generalizability and representativeness of the research [27,30]. Third, the study only included respondents from South Africa, so future studies might concentrate on other regions and countries to acquire a more comprehensive understanding of the adoption and usage of Instagram mega-influencers from a geographical and cultural perspective. However, it is important to note that South Africa is not represented by a singular homogenous regional culture but consists of many different cultural and ethnic groups and has 12 official languages [169]. Future studies could investigate if there are differences between the cultural groups regarding the usage of Instagram mega-influencers in South Africa. Fourth, the investigation only included members from the Generation Z cohort, so further inquiries could investigate other cohorts or conduct comparative studies between different cohorts, for example, Generations Y and X and Baby Boomers. Fifth, the study focused on mega-influencers, but it could also explore nano-, micro-, and macro-influencers, as well as consider specific mega-influencers. Finally, the research data were self-reported by the respondents, so future research could consider data from multiple sources (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and longitudinal data) and use more objective measures (e.g., observational, physiological, and behavioral data) to reduce this limitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and R.D.; methodology, A.M. and R.D.; validation, R.D.; formal analysis, R.D.; investigation, A.M.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and R.D.; writing—review and editing, R.D.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was not given any external financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was executed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Faculty Research Ethics Committee (FBMSREC0722021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was acquired from all participants in the investigation.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this research can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly accessible due to constraints, as the thesis is currently under examination and is part of a larger study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duffett, R.G.; Miller, N.V. Modelling Online Advertising Design Quality Influences on Millennial Consumer Attitudes in South Africa. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 14, 108–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, T.; Oliveira, R. Brands as Drivers of Social Media Fatigue and Its Effects on Users’ Disengagement: The Perspective of Young Consumers. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Le, T.T.H.; Nguyen, H.K.; Khuat, H.T.; Phan, H.T.T.; Vu, H.T. Young Consumers’ Impulse Buying Tendency on Social Media: An Empirical Analysis in Vietnam in Light of the LST Theoretical Perspective. Young Consum. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenyapar, H.N.D. A Comprehensive Analysis of Influencer Types in Digital Marketing. Int. J. Manag. Adm. 2024, 8, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuqair, S.; Filieri, R.; Viglia, G.; Mattila, A.S.; Pinto, D.C. Leveraging Online Selling Through Social Media Influencers. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Influencer Advertising–Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/advertising/influencer-advertising/worldwide (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Statista. Influencer Advertising-South Africa. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/advertising/influencer-advertising/south-africa#:~:text=Ad%20spending%20in%20the%20Influencer,US%2444.28m%20by%202029 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A. The Role of Social Media Marketing Activities in Driving Self-Brand Connection and User Engagement Behaviour on Instagram: A Moderation-Mediation Approach. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, A.B.; Adzovie, D.E. Understanding the Moderating Role of E-WoM and Traditional Media Advertisement Toward Fast-Food Joint Selection: A Uses and Gratifications Theory. J. Foodservice Bus. Res. 2024, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A. To Be or Not to Be (an Ad): Advertising Students’ Understanding of Instagram In-Feed Native Advertising. J. Advert. Educ. 2024, 28, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolina, M.W. Youth, Generations, and Generational Research. Polit. Sci. Q. 2024, 139, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, E.; Ivan, L. Not Only People Are Getting Old, the New Media Are Too: Technology Generations and the Changes in New Media Use. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 3588–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes Among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Do, B.; Yourell, J.; Hermer, J.; Huberty, J. Digital Methods for the Spiritual and Mental Health of Generation Z: Scoping Review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, 48–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffett, R.G.; Charles, J.R. Assessing Antecedents of Google Shopping Ads Intention to Purchase: A Multigroup Analysis of Generation Y and Z. Young Consum. 2025, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zungu, S.; Magadlela, Z. Innovation for a New Generation: How Gen Z is Redefining Brand Loyalty in the Digital Age. 2024. Available online: https://www.bizcommunity.com/article/innovation-for-a-new-generation-how-gen-z-is-redefining-brand-loyalty-in-the-digital-age-700802a#more (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Ahmed, A.; Rathore, T. The Evolution of Influencer Marketing. In Advances in Data Analytics for Influencer Marketing: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Dutta, S., Rocha, A., Dutta, P.K., Bhattacharya, P., Singh, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angmo, P.; Mahajan, R. Virtual Influencer Marketing: A Study of Millennials and Gen Z Consumer Behaviour. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2024, 27, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, R.; Liao, J. Mega-Influencer Follower Effect: The Mediating Role of Sense of Control in Brand Attitudes, Purchase Intentions and Engagement. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhriah, S.A. The Influence of Social Media Influencers on the Purchase Intention of Fashion Products for Generation Z on the Instagram Application. Formosa J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 3, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitria, F.; Adisti, D.T.; Dea, D.; Gumelar, A.; Setiawan, A. Exploration of the Role of TikTok Content: Influencer Strategy, Affiliate Marketing, and Online Customer Reviews in Influencing Generation Z Purchasing Decisions at Shopee. Athena J. Soc. Cult. Soc. 2024, 2, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J. Influencers Marketing and Its Impacts on Sustainable Fashion Consumption Among Generation Z. J. Soft Comput. Decis. Anal. 2024, 2, 118–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; Min, M.K. Gen Z Consumers’ Sustainable Consumption Behaviours: Influencers and Moderators. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina, A.S.; Marsasi, E.G. Influencer’s Trustworthiness and Attitude to Increase Purchase Intention in Generation Z Based on Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Pamat. J. Ilm. Univ. Trunojoyo 2024, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, T.; Ikram, M. Navigating the Digital Landscape: Impact of Instagram Influencers’ Credibility on Consumer Behaviour Among Gen Z and Millennials. Media Literacy Acad. Res. 2024, 7, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tseng, C.J. The Impact of Social Media Influencer Characteristics on Purchase Intentions: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Regulatory Focus to Perceived Uniqueness. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2024, 14, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băltescu, C.A.; Untaru, E.N. Exploring the Characteristics and Extent of Travel Influencers’ Impact on Generation Z Tourist Decisions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, O.; Ashman, R.; Haenlein, M. Leveraging Livestreaming to Enrich Influencer Marketing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2025, 67, 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholkina, V.; Chesnokova, E.; Zelenskaya, E. Virtual or Human? The Impact of the Influencer Type on Gen Z Consumer Outcomes. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2025, 34, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghraoui, S.; Khrouf, L. Instagram Live-Streamings: How Does Influencer–Follower Congruence Affect Gen Z Trust, Attitudes and Intentions? Young Consum. 2025, 26, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, R.H.K.; Windasari, N.A. Proposed Social Media Marketing Content Strategy Through Instagram to Increase Sales Performance of Fashion Business (Case Study: DMC.id). J. Econ. Bus. UBS 2023, 12, 651–673. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, S.; Fatima, T. Investigating the Influence of Cloth Branding Advertisements on Consumer Buying Behaviour: Insights from Instagram. Pak. J. Soc. Res. 2023, 5, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallah, G.M.; Dandis, A.O.; Al Haj Eid, M.B. The Impact of Instagram Utilization on Brand Management: An Empirical Study on the Restaurants Sector in Beirut. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2024, 27, 287–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Baig, S. Promoting Tourism via Instagram: A Study of Instagram Users and the Role of Tourism Companies in Pakistan. Journ. Polit. Soc. 2024, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalib, A.S.; Ardiansyah, M. The Role of Instagram Influencers in Affecting Purchase Decision of Generation Z. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Stud. 2022, 2, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.L.; Ho, H.-C. Impact of Celebrity, Micro-Celebrity, and Virtual Influencers on Chinese Gen Z’s Purchase Intention through Social Media. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Choi, Y.; Lee, H. Gen Z Travellers in Instagram Marketplace: Trust, Influencer Type, Post Type and Purchase Intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 48, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D.M. The Influencer Effect: Exploring the Persuasive Communication Tactics of Social Media Influencers in the Health and Wellness Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vassey, J.; Valente, T.; Barker, J.; Stanton, C.; Li, D.; Laestadius, L.; Cruz, T.B.; Unger, J.B. E-Cigarette Brands and Social Media Influencers on Instagram: A Social Network Analysis. Tob. Control 2023, 32, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustian, K.; Hidayat, R.; Zen, A.; Sekarini, R.A.; Malik, A.J. The Influence of Influencer Marketing in Increasing Brand Awareness and Sales for SMEs. Technol. Soc. Perspect. 2023, 1, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastrygina, T.; Lim, W.M.; Jopp, R.; Weissmann, M.A. Unraveling the Power of Social Media Influencers: Qualitative Insights into the Role of Instagram Influencers in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 214–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Baneen, U.; Raza, A. The Impact of Instagram Influencers on Purchase Intention of Female Users. Media Commun. Rev. 2024, 4, 90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More Than Meets the Eye: The Functional Components Underlying Influencer Marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurine, S.N. Consumer Behaviour and the Role of Influencer Marketing on Purchase Decisions. Master’s Thesis, Mykolas Romeris University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, M.I.; Salo, J. Analyzing the Influence of Social Media Influencer’s Attributes and Content Aesthetics on Endorsed Brand Attitude and Brand-Link Click Behavior: The Mediating Role of Brand Content Engagement. J. Promot. Manag. 2024, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R.; Casais, B. Micro, Macro and Mega-Influencers on Instagram: The Power of Persuasion via the Parasocial Relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, R.; Ory, A.; Zheng, X. Influence or Advertise: The Role of Social Learning in Influencer Marketing. Master’s Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, N.; Föhl, U.; Zagermann, L. Big or Small? Impact of Influencer Characteristics on Influencer Success, with Special Focus on Micro-Versus Mega-Influencers. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2024, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Santiago, J.; Tiago, F. Mega or Macro Social Media Influencers: Who Endorses Brands Better? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, F.; Lee, J.M.; Park, J.; Septianto, F.; Seo, Y. How Micro-(vs. Mega-) Influencers Generate Word of Mouth in the Digital Economy Age: The Moderating Role of Mindset. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Dew, R.; Iyengar, R. Mega or Micro? Influencer Selection Using Follower Elasticity. J. Mark. Res. 2024, 61, 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keasey, K.; Lambrinoudakis, C.; Mascia, D.V.; Zhang, Z. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on the Financial Market Performance of Firms. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2025, 31, 745–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Shoenberger, H.; Kim, D.; Thorson, E.; Zihang, E. Novelty vs. Trust in Virtual Influencers: Exploring the Effectiveness of Human-Like Virtual Influencers and Anime-Like Virtual Influencers. Int. J. Advert. 2025, 44, 453–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.R.; Campell, C.; Sands, S. What Drives Consumers to Engage with Influencers? Segmenting Consumer Response to Influencers: Insights for Managing Social-Media Relationships. J. Advert. Res. 2022, 8, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Kishore, K.; Gokhale, N. Social Media Influencers and Consumer Engagement: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2106–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, D.; Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V. Investigating the Impact of Authenticity of Social Media Influencers on Followers’ Purchase Behaviour: Mediating Analysis of Parasocial Interaction on Instagram. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2377–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sous, N.; Almajali, D.; Alsokkar, A. Antecedents of Social Media Influencers on Customer Purchase Intention: Empirical Study in Jordan. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2023, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. Virtual Influencers’ Attractiveness Effect on Purchase Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model of the Product–Endorser Fit with the Brand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.R.; Quintana, J.G.; Riaño, E.R. Impact and Engagement of Sport & Fitness Influencers: A Challenge for Health Education Media Literacy. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2023, 13, 202334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.J.d.S.; Cardoso, A.; Canavarro, A.; Figueiredo, J.; Garcia, J.E. Digital Influencers’ Attributes and Perceived Characterizations and Their Impact on Purchase Intentions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratina, D.; Faganel, A. Understanding Gen Z and Gen X Responses to Influencer Communications. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nilashi, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Asadi, S.; Khoshkam, M. Determinants of Followers’ Purchase Intentions Toward Brands Endorsed by Social Media Influencers: Findings from PLS and fsQCA. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 888–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, V.; Ye, Z. Influencers’ Instagram Imaginaries as a Global Phenomenon: Negotiating Precarious Interdependencies on Followers, the Platform Environment, and Commercial Expectations. Convergence 2024, 30, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N. From Likes to Sustainability: How Social Media Influencers Are Changing the Way We Consume. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.T.; Weng, Y.J. Influence of Social Media Influencer Authenticity on Their Followers’ Perceptions of Credibility and Their Positive Word-of-Mouth. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Chaudhary, N.; Gusai, O.P. Impact of Social Media Influencers’ Credibility and Similarity on Instagram Consumers’ Purchase Intention. Rev. Prof. Manag. J. Manag. 2023, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R.; Salim, M. The Influence of Micro-Influencers and Content Marketing Through Customer Engagement on Purchasing Decisions. Gema Wiralodra 2023, 15, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eniola, O. Influence of Instagram Influencers on Oriflame Product Campaign on Students of the University of Benin. Honours Thesis, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lie, S.; Sitinjak, T. The Influence of Influencer Marketing on Instagram Towards Secondate Brand Awareness in Jakarta. J. Komun. Bis. 2024, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veybitha, Y.; Alfansi, L.; Salim, M.; Darta, E. Critical Review: Factors Affecting Online Purchase Intention Gen Z. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2021, 4, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewe, S.Y.; Tjiptono, F. Green Behaviour Among Gen Z Consumers in an Emerging Market: Eco-Friendly Versus Non-Eco-Friendly Products. Young Consum. 2023, 24, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K.; Kundu, N.; Ahluwalia, I.S. Does Socio-Demographic, Green Washing, and Marketing Mix Factors Influence Gen Z Purchase Intention Towards Environmentally Friendly Packaged Drinks? Evidence from Emerging Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlić, I. Baby Boomers and Gen Z: The Role of Consumer Ethnocentrism on Purchase Intention. Dubrov. Int. Econ. Meet. 2024, 9, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Ochoa, J.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. AI-Driven Virtual Travel Influencers and Ethical Consumerism: Analysing Engagement with Sena Zaro’s Instagram Content. Young Consum. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Menawy, S.M.A.; Saleh, P.S. How Does the Mediating Role of the Use of Social Media Platforms Foster the Relationship Between Employer Attractiveness and Gen Z Intentions to Apply for a Job? Futur. Bus. J. 2023, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Chawla, Y. Gen Z’s Attitude Towards Green Image Destinations, Green Tourism, and Behavioural Intention Regarding Green Holiday Destination Choice: A Study in Poland and India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tănase, M.O.; Nistoreanu, P.; Dina, R.; Georgescu, B.; Nicula, V.; Mirea, C.N. Gen Z Romanian Students’ Relation with Rural Tourism–An Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumley, C. Instagram and Influencer Marketing: An Empirical Study of the Parasocial Interaction Theory and Its Effects on Purchase Intention. Master’s Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sandra, J.; Indrayanti, S.; Suryana, A. Influencer Marketing Strategies and Brand Image in Boosting Consumer Purchase Intent: The Role of Customer Support Intervention. J. Inform. Ekon. Bisness 2024, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hung-Baesecke, C.J.F.; Chen, Y.R.R. Social Media Influencer Effects on CSR Communication: The Role of Influencer Leadership in Opinion and Taste. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2024, 61, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Verma, N.K. Social Media Platforms and User Engagement: A Multi-Platform Study on One-Way Firm Sustainability Communication. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C. Impact of Social Media Influencers’ Endorsement on Application Adoption: A Trust Transfer Perspective. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2019, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, R.; Kapoor, D. Influencer Review Effect on Customer Purchase Intention: An Extension of TAM. Int. J. E-Business Res. 2021, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, S.F.N.; Bujang, A.; Haris, N.; Sadikin, S. The Acceptance of Islamic Applications Founded by Social Media Influencers. Borneo Int. J. 2022, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Xue, F. Effects of Instagram User-Generated Content on Travel Inspiration and Planning: An Extended Model of Technology Acceptance. J. Promot. Manag. 2022, 28, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M.S. New Trend in Online Shopping: L-Commerce (Live Stream Commerce) and a Model Proposal for Consumer Adoption. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2024, 19, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Oliveira, A.; Abreu, A.; Mesquita, A. Social Networks and Digital Influencers in the Online Purchasing Decision Process. Information 2024, 15, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Rehman, A.; Al Rousan, R. From Screen to Plate: An Investigation of How Information by Social Media Influencers Influence Food Tasting Intentions Through the Integration of IAM and TAM Models. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 2, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Li, X.; Choi, S. Exploring the Influence of Short Video Platforms on Tourist Attitudes and Travel Intention: A Social-Technical Perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 31, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismueller, T.; Harrgan, P.; Wang, S.; Souta, G.N. Influencer Endorsements: How Advertising Disclosure and Source Credibility Influence Consumer Intention on Social Media. Aust. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFarraj, O.; Alalwan, A.A.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Baabdullah, A.; Aldmour, R.; Al-Haddad, S. Examining the Impact of Influencers’ Credibility Dimensions: Attractiveness, Trustworthiness and Expertise on the Purchase Intention in the Aesthetic Dermatology Industry. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2021, 31, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añaña, E.; Barbosa, B. Digital Influencers Promoting Healthy Food: The Role of Source Credibility and Consumer Attitudes and Involvement on Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Bakshi, A. Exploring the Impact of Beauty Vloggers’ Credible Attributes, Parasocial Interaction, and Trust on Consumer Purchase Intention in Influencer Marketing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, S. Wear in or Wear Out: How Consumers Respond to Repetitive Influencer Marketing. Internet Res. 2024, 34, 810–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromhout, D.; Duffett, R. Exploring the Impact of Student Developed Marketing Communication Tools and Resources on SMEs Performance and Satisfaction. Small Bus. Int. Rev. 2022, 6, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R.G.; Thomas, S. Health Nonprofit Organizations Use of Social Media Communication and Marketing During COVID-19: A Qualitative Technology Acceptance Model Viewpoint. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open 2024, 10, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Duffett, R.G. Using Social Media as a Marketing Communication Strategy: Perspectives from Health-Related Non-Profit Organizations. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthinus, J.; Duffett, R.G.; Knott, B. Social Media Adoption as a Marketing Communication Tool by Non-Professional Sports Clubs: A Multiple Case Study Approach. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2025, 26, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, M.M.; Fadhilatunisa, D.; Yuanita, B.; Sari, N.R. The Use of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Measure Behavioral Intention Users of Zahir Accounting Software. Assets J. Ekon. Manaj. Akunt. 2022, 12, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, U.W.E.; Darma, G.S. The Intention to Use Blockchain in Indonesia Using Extended Approach Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). CommIT J. Commun. Inf. Technol. 2022, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujood, B.N.; Siddiqui, S. Consumers’ Intention towards the Use of Smart Technologies in Tourism and Hospitality (T&H) Industry: A Deeper Insight into the Integration of TAM, TPB and Trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 1412–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.; Duffett, R. The Role of Brand Awareness and Trust on Purchase Intent in Google Shopping Ads and Demographic Factor Influences among Millennials and Generation Z. In Information Management and Technology: The Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Business and Management Dynamics (ICBMD); Twum-Darko, M., Ed.; BP International: West Bengal, India, 2025; pp. 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraule, M.; Duffett, R. The Influence of Emoji Digital Marketing and Demographic Factors on Generation Z’s Purchase Intention Decisions. In Information Management and Technology: The Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Business and Management Dynamics (ICBMD); Twum-Darko, M., Ed.; BP International: West Bengal, India, 2025; pp. 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthinus, J.; Duffett, R.; Knott, B. Social Media Marketing in Non-Professional Rugby Clubs: A Qualitative Viewpoint Using the Technology Acceptance Model. In Information Management and Technology: The Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Business and Management Dynamics (ICBMD); Twum-Darko, M., Ed.; BP International: West Bengal, India, 2025; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Duffett, R. Leveraging Social Media Marketing in Healthcare-Based Non-Profit Organisations: Insights from the Technology Acceptance Model. In Information Management and Technology: The Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Business and Management Dynamics (ICBMD); Twum-Darko, M., Ed.; BP International: West Bengal, India, 2025; pp. 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorser’s Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Yoon, H.J. The Effectiveness of Influencer Endorsements for Smart Technology Products: The Role of Follower Number, Expertise Domain and Trust Propensity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, A.H.; Wani, I.S.; Rather, A.H. Impact of Social Media Influencers Credibility on Destination Brand Trust and Destination Purchase Intention: Extending Meaning Transfer Model? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Zamora, J. 2023. Effects of Physical Appearance of Ad Endorsers Featured in Gay-Targeted Ads, Explained by Endorser Match-Up and Identification. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 408–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Mercado, T.; Bi, N.C. “Unintended” Marketing Through Influencer Vlogs: Impacts of Interactions, Parasocial Relationships, and Perceived Influencer Credibility on Purchase Behaviours. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnoosh, S.; Dickson, G.; Naylor, M. Endorsement and Promoting Sport and Physical Activity to Young People: Exploring Gender and the Career Status of Athlete Endorsers. Manag. Sport Leis. 2023, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajnef, K. The Effect of Social Media Influencers’ on Teenagers Behaviour: An Empirical Study Using Cognitive Map Technique. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19364–19377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, S.; Arslan, H.M.; Baydaş, A.; Pazvant, E. The Effect of Social Media Influencers’ Credibility on Consumer’s Purchase Intentions through Attitude toward Advertisement. ESIC Mark. 2023, 53, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.B.; Lee, V.H.; Hew, J.J.; Leong, L.Y.; Tan, G.W.H.; Lim, A.F. Social media influencers: An effective marketing approach? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, M.; Mustikowati, R.I.; Chrismardani, Y. Why Customers Buy an Online Product? The Effects of Advertising Attractiveness, Influencer Marketing and Online Customer Reviews. LBS J. Manag. Res. 2023, 21, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Siddiqi, U.I.; Gugnani, R.; Islam, T.; Attri, R. The Potency of Audiovisual Attractiveness and Influencer Marketing: The Road to Customer Behavioural Engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, C.; Méon, P.G. Attractiveness vs. Partisan Stereotypes. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2024, 219, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, G.; Datta, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Paul, I. Effect of Rich Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) to Predict Online Purchase Intention in Indian Context Using the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning and SEM-FsQCA. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 3, 3270–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S.; Gandhi, S. Catalysing Consumer Behaviour: Analysing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intentions and Attitudes. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 7110–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourela, M. Successive Intertwining of Young Consumers’ Reliance on Social Media Influencers. Communications 2024, 49, 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, H. Beautifully Green: Beauty Vloggers’ Assessments of Sustainable Cosmetic Products: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, L.; Bansal, R.; Pruthi, N.; Khaskheli, M.B. Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customer Engagement and Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Hameed, I.; Saeed, S.A. How Do Social Media Influencers Inspire Consumers’ Purchase Decisions? The Mediating Role of Parasocial Relationships. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1416–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipudin, M.N.S.; Abdullah, N.A.; Foo, K.W.; Hassim, N.; Tóth, Z.; Chan, T.J. The Influence of Social Media Influencer (SMI) and Social Influence on Purchase Intention Among Young Consumers. SEARCH J. Media Commun. Res. 2023, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Venciute, D.; Mackeviciene, I.; Kuslys, M.; Correia, R.F. The Role of Influencer–Follower Congruence in the Relationship Between Influencer Marketing and Purchase Behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 4, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesthi, H.K.; Prasetyo, B.D.; Safitri, R. Rivalry of Celebrity and Influencer Endorsement for Advertising Effectiveness. Bricolage J. Magister Ilmu Komunik. 2024, 10, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, N.; Mulye, R.; Japutra, A. How Do Consumers Interact with Social Media Influencers in Extraordinary Times? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursyabani, A.P.; Silvianita, A. The Effects of Celebrity Endorser and Electronic Word of Mouth on Purchase Intention with Brand Image as Intervening Variable on Wardah Lipstick Products. Int. J. Adv. Res. Econ. Finance 2023, 5, 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanti, N.K.A. The Influence of Celebrity Instagram Endorsement and Word of Mouth on Online Purchase Decisions with Brand Image as a Mediator. EKOMBIS REV. Sci. J. Econ. Bus. 2024, 12, 1641–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]