Abstract

Green advertising messages often face challenges of abstraction and outcome ambiguity. To address this, we apply the framing effect theory to explore how concrete versus abstract expressions in green advertising interact with consumer perceptions. Drawing on the Stereotype Content Model (SCM), we propose a congruence framework: concrete messages align with competence appeals, while abstract messages align with warmth appeals. Through two experiments, we demonstrate that such congruence significantly enhances green purchase intention. Experiment 1 establishes the interaction effect between message framing (concrete vs. abstract) and appeal type (competence vs. warmth), revealing that concrete–competence and abstract–warmth pairings outperform mismatched conditions. Experiment 2 further validates advertising attitudes as a mediator and product involvement as a moderator, clarifying boundary conditions. These findings advance the theoretical understanding of framing effects in sustainability communication and offer actionable strategies for marketers: aligning message specificity (concrete/abstract) with appeal dimensions (competence/warmth) can amplify consumer engagement, particularly when tailored to product contexts.

1. Introduction

Amid escalating global environmental challenges, green consumption has emerged as a critical pathway to reconcile ecological preservation with economic growth. Global household consumption contributes approximately 28–36% to annual greenhouse gas emissions (2015–2020 baseline) [1]. In the current ecological context, advertising and communication emerge as valuable tools for raising awareness and encouraging sustainable behavior [2]. Companies have responded by advertising their sustainability initiatives, practices, and products [3]. Green advertising plays a pivotal role in bridging corporate sustainability initiatives and consumer behavior by disseminating eco-friendly values and product information. Specifically, eco-friendly values activate consumers’ sense of obligation to align purchases with pro-environmental norms [4]. Concurrently, concrete product information enhances cognitive trust through verifiable evidence [5], whereas abstract narratives evoke emotional engagement to drive impulse decisions [6]. The interplay of these dual pathways explains why green advertising significantly increases purchase intentions for sustainability-conscious segments [7]. Unlike traditional advertising, green advertising emphasizes long-term environmental benefits, yet its effectiveness is often hampered by the inherent abstractness and uncertainty of these benefits [8]. Consumers frequently question the tangible impact of green choices (e.g., “Does purchasing an eco-friendly backpack truly mitigate environmental harm?”), leading to reliance on cognitive shortcuts during decision-making [9]. While traditional advertising frameworks, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [10], emphasize rational decision-making through attitudes and subjective norms, they often overlook the heuristic nature of consumer judgments in information-saturated environments. In contrast, the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) [11] provides a dual-axis framework that directly maps onto consumers’ spontaneous evaluations of green advertisements. The Stereotype Content Model (SCM), which categorizes perceptions into competence and warmth, offers a lens to understand how consumers simplify complex green messaging [11].

A critical gap persists in aligning green advertising strategies with cognitive-processing styles. While concrete framing (e.g., quantifiable metrics like “reduces 30% carbon emissions”) may reduce decision uncertainty [12], abstract framing (e.g., secure a greener future) can foster emotional resonance with long-term goals [13]. However, the interplay between these frameworks and the dual dimensions of advertising appeals—competence and warmth—remains underexplored. Existing studies present conflicting hypotheses. Some argue that concrete information enhances credibility [14], while others suggest abstract narratives better engage ethically motivated consumers [15]. This divergence underscores the need to examine how the congruence between message framing and appeal type shapes consumer responses.

This study addresses these gaps by proposing a framing–appeal congruence hypothesis: concrete framing paired with competence appeals amplifies perceived efficacy, whereas abstract framing paired with warmth appeals strengthens ethical identification. Through two experiments, we investigate (1) how this congruence enhances green purchase intention, (2) the mediating role of advertising attitudes, and (3) the moderating effect of product involvement. The results demonstrate that concrete–competence pairings outperform mismatched conditions for high-involvement products (e.g., electric vehicles), while abstract–warmth pairings are more effective for low-involvement products (e.g., eco-friendly cleaning supplies). Drawing on dual-system theories of decision-making [16], high-involvement purchases, such as electric vehicles, engage System 2 processing—a deliberate, effortful mode. In such contexts, concrete framing paired with competence appeals reduces information search costs [17] by providing diagnostic attributes that facilitate comparative evaluations. Conversely, low-involvement decisions, exemplified by eco-friendly cleaning supplies, predominantly activate System 1 processing—a heuristic-driven mode reliant on affective cues and symbolic associations. Abstract framing combined with warmth appeals capitalizes on this heuristic processing, thereby bypassing exhaustive information searches. These findings advance sustainability communication theory by clarifying the psychological mechanisms underlying green advertising effectiveness and by providing actionable strategies for tailoring messages to consumer cognition and product contexts.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Consumer Response

The extant research has extensively explored how green advertising influences consumer decision-making through emotional appeals and cognitive processing, generating a robust theoretical foundation [18]. Nevertheless, significant challenges persist in achieving effective communication. Consumers often perceive the environmental benefits of green consumption as abstract and ambiguous—a cognitive uncertainty that complicates decision-making processes and induces procrastination [4]. The benefits of green consumption exhibit temporal delay, making it challenging for individual consumers to directly observe the immediate environmental impacts of their behaviors, thereby obscuring the causal relationship between their actions and environmental outcomes. In contrast, traditional consumption demonstrates immediate and private benefits that are more readily perceptible. According to the Construal Level Theory [19], environmental issues are typically perceived by consumers as abstract concepts with high psychological distance, rather than low-distance events directly relevant to themselves. This psychological distance hinders consumers’ concrete cognitive representations of green product benefits. The ambiguous perception of green product benefits consequently diminishes their perceived value, heightening the price sensitivity towards premium pricing [5]. Such ambiguity not only undermines the advertising efficacy but also poses barriers to the growth of green markets. A critical solution lies in optimizing the alignment between advertising information framing (e.g., concrete vs. abstract) and appeals (e.g., competence vs. warmth), which may reduce cognitive load and enhance persuasion outcomes, particularly in improving consumers’ perceived credibility of environmental claims and their willingness to pay for green products.

Consumer response—defined as the psychological and behavioral reactions spanning initial perceptions, purchase intentions, and actual behaviors—serves as a pivotal metric for evaluating advertising effectiveness [18,20]. It reflects the integration of attitudes (e.g., toward brands, products, or firms) and behavioral intentions (e.g., willingness to pay premiums, repurchase loyalty, or word-of-mouth advocacy). Drawing on Bhattacharya and Sen’s [18] taxonomy, this study categorizes consumer responses into internal and external responses. Internal responses include cognitive–affective states, brand attitudes [21], and corporate evaluations. External responses include observable behaviors, such as purchase decisions and post-purchase loyalty. By focusing on advertising attitudes (internal) and purchase intentions (external), this research provides a dual-channel framework to decode how green advertising strategies activate and sustain consumer engagement.

2.2. The Congruence Effect of Green Advertising Appeals and Information Framing

2.2.1. Warmth vs. Competence Appeals

The inherent complexity of information and the constraints on cognitive resources drive individuals to rely on stereotype activation when evaluating objects, impressions, or judgment tasks [11,22]. The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) posits that social perceptions are simplified into two universal dimensions: warmth (e.g., emotional warmth conveyed by a brand or advertisement, such as a friendly, approachable tone or perceived social care) and competence (e.g., perceived efficacy, skill, or goal-achieving ability) [11]. These dimensions extend to brand evaluations: consumers perceive brands as “warm” when they exhibit prosocial intentions (e.g., environmental stewardship) and “competent” when demonstrating technical superiority (e.g., energy efficiency) [23].

Recent applications of SCM in advertising research seek to identify the “golden quadrant”—the optimal balance of warmth and competence—though their relative importance depends on contextual factors such as product type, target audience traits, and appeal characteristics [24]. For instance, low-involvement products (e.g., eco-friendly utensils) amplify warmth-related perceptions, whereas high-involvement products (e.g., solar panels) prioritize competence-driven evaluations [23,25]. SCM further suggests that consumers spontaneously assess brands or organizations through dual lenses, with intentions (warmth), such as “Does the entity act with societal or ethical goodwill?”, and capability (competence), such as “Can the entity effectively deliver on its promises?”

In green consumption contexts, this translates to consumers evaluating products based on warmth and competence. At the corporate level, warmth perceptions reflect emotional resonance with a company’s ethical stance, while competence perceptions hinge on objective assessments of its technical capabilities [26]. Brands perceived as both warm and competent elicit stronger positive attitudes and purchase intentions [27].

Building on this framework, we classify green advertising appeals into two categories. Competence appeals emphasize functional attributes (e.g., efficiency, innovation, and performance) to align with rational decision-making processes. Example: “Our technology cuts energy use by 50%—verified by third-party audits”. Warmth appeals emphasize a brand’s perceived kindness and friendliness toward consumers, such as, for example, “Book a free virtual session with our stylists—we’re here to help you look good, and love your sustainable wardrobe”.

2.2.2. Concrete vs. Abstract Information Frameworks

The framing effect refers to the phenomenon in which identical information, when presented in different ways, leads to different interpretations and decisions by the receiver. In other words, variations in the wording or structure of information can result in different outcomes, prompting distinct choices and behaviors. This effect is also evident in the field of advertising. Due to advancements in technology, the evolution of marketing strategies, and the growing demand for personalized consumer aesthetics, the content and presentation of advertising information have undergone a paradigm shift, transitioning from mass broadcasting to hyper-personalized, multi-format delivery systems. Advertisers leverage tactics like retargeted ads (e.g., recycled product reminders), context-aware messaging (e.g., energy-saving tips based on regional usage), and authenticity-driven influencer campaigns to amplify persuasion. Previous research on advertising information has shown that different information frames can influence consumer perceptions and, consequently, their decision-making processes. This cognitive bias is further complicated by the temporal positioning of information, as evidenced by the primacy effect and the recency effect [28,29]. In the field of advertising, these effects interact with framing strategies. For instance, when concrete information (e.g., quantitative environmental metrics) is positioned early in a message, the primacy effect amplifies its salience in shaping consumers’ initial attitudes. Conversely, abstract appeals (e.g., symbolic imagery of sustainability) placed at the end may leverage the recency effect to enhance memorability during decision-making [30]. Advertisers thus face a dual challenge: optimizing both how information is framed (concrete vs. abstract) and when it is presented (sequence) to maximize persuasive impact.

Studies on the relative concepts of “concreteness” and “abstractness” are primarily found in the fields of education and neuroimaging [31,32]. In education, discussions typically focus on the advantages and disadvantages of concrete vs. abstract concepts in the context of educational materials. Neuroimaging research aims to uncover the specific mechanisms by which concrete and abstract concepts are processed in the human brain, including the neural regions activated during this processing. However, limited research has explored the use of concrete and abstract information as opposing frameworks in advertising.

This study posits that concrete information refers to environmental messages conveyed through specific, quantifiable facts and data, such as the percentage of eco-friendly materials used or precise data on energy-saving outcomes. Such information frameworks are typically clear and easily understandable for consumers, thus enhancing their attitudes toward the advertisement and increasing their purchase intentions. In contrast, abstract information relies more on emotional appeals and ideological expressions, such as emphasizing the importance of environmental protection or conveying a sense of responsibility for future generations. Abstract information influences consumer attitudes and behavior by resonating with their emotions and values [33].

According to Construal Level Theory, as psychological distance from the perceiver’s immediate experience increases along temporal, spatial, social, or hypothetical dimensions, mental representations become more abstract, decontextualized, and structured around goal-relevant features. Conversely, objects with a lower psychological distance are perceived in a more concrete manner. Thus, concrete frames transform abstract concepts into specific, actionable information through detailed and contextualized descriptions. This reduces the complexity of consumers’ understanding of the advertisement and minimizes uncertainty in their decision-making process. Concrete frameworks provide direct, actionable information, such as product-usage instructions or performance advantages, which help to build consumer trust in the advertisement. In contrast, abstract frameworks present generalized and macro-level information, emphasizing the long-term benefits of products or behaviors. By highlighting the overall and enduring effects, such frameworks encourage consumers to focus on future environmental benefits or the significance of corporate actions, thereby fostering emotional resonance and value-based identification.

In advertising, the level of specificity is determined by the dual dimensions of quantitative precision and affective orientation. When advertisements include quantifiable, context-bound data, they are considered concrete. Conversely, abstract information is characterized by a lack of quantifiable details and reliance on symbolic narratives to activate affective valuations. In green advertising, concrete information refers to the use of specific, clear data and environmental benefits to depict a company’s eco-friendly actions [34]. Existing research primarily examines quantitative precision as the key differentiator. Khatoon and Rehman demonstrated that advertisements with numerically precise claims are perceived as more credible than those using non-quantified descriptions [35]. Similarly, Krishen et al. suggested that objectively verifiable information (concrete framing) reduces consumer skepticism compared to subjective assertions (abstract framing) [36]. However, these studies predominantly address the cognitive dimension of concreteness, leaving the affective component underexplored.

Recent studies highlight the synergy between abstract framing and affective messaging [37]. Jäger and Weber systematically compared self-benefit appeals (e.g., health advantages) versus other-benefit appeals (e.g., environmental welfare), alongside abstract versus concrete framing, revealing that abstract–other–benefit combinations uniquely drive green purchase intentions [38]. This aligns with Neureiter and Stubenvoll’s caution: while abstract claims (e.g., “committed to sustainability”) can enhance engagement through emotional resonance, their lack of verifiable details also increases greenwashing risks [39]. Our framework reconciles these findings by positing that the effectiveness of abstract framing hinges on its alignment with warmth-based appeals that authentically activate communal values, whereas mismatches (e.g., abstract–competence) exacerbate skepticism.

2.2.3. Matching Effect

Previous studies have shown that concrete information (e.g., specific eco-friendly behaviors or visible green product effects) is more easily processed and understood by consumers, thereby generating stronger behavioral intentions. In contrast, abstract information is more effective in fostering consumers’ long-term environmental awareness and brand loyalty [19]. Chandran and Menon found that concrete information is more effective in promoting short-term green purchasing behavior, while abstract information plays a key role in cultivating consumers’ long-term environmental attitudes [40].

Information framing, a core concept in behavioral decision theory, can be categorized into three primary types: goal framing (emphasizing gains vs. losses), risky choice framing (presenting options as risks vs. certainty), and attribute framing (highlighting specific features positively or negatively). These classifications reflect how semantically equivalent information, when framed differently, systematically alters decision-making heuristics and behavioral outcomes [41]. While information framing can reveal the impact of different presentation styles on consumer responses, the way consumers react to advertising also depends on their intrinsic perceptual characteristics (such as warmth perception and competence perception). The matching effect between the information framework and the advertising appeal provides a more comprehensive understanding of consumers’ cognitive processing, as a well-matched frame can activate more efficient processing of the advertisement content, thereby enhancing consumer attitudes and behavioral intentions. Importantly, this process operates within the communication feedback loop; the role of media context and individual differences in message decoding warrants further investigation in ecological settings. Warmth and competence, as the two core dimensions of advertising appeals, are not only prevalent in consumer perceptions of brands and products but also directly influence emotional resonance and trust levels. Combining the advertising information framework with these two perceptual dimensions not only refines our understanding of consumer responses but also uncovers the boundary conditions of advertising messages in different contexts, thus addressing the complex interaction mechanisms that single-variable studies fail to explain. This dual-perspective approach is more aligned with the psychological dynamics of real-world consumption scenarios.

The primary goal of businesses or brands when using advertising to promote green products is to align the advertising appeal with the brand’s green image positioning. Therefore, companies tend to choose different advertising frames to present their brand image to consumers. Typically, the use of concrete advertising information aims to convey specific benefits to consumers, such as the immediate advantages of purchasing a green product or using an energy-saving product, or the clear benefits it brings to consumers and their families. In contrast, abstract green advertising information involves more conceptual and principled content, emphasizing the macro-level benefits of green products for the environment, the industry, and resource conservation. These long-term benefits appeal to the broader societal impact, which better reflects the warmth perception of the brand.

According to the Construal Level Theory (CLT), individuals’ mental representations of information depend on their perceived psychological distance [19]. Specifically, people tend to process psychologically distant objects or events through abstract construals, which focus on decontextualized core values, whereas psychologically proximal objects or events are processed through concrete construals, emphasizing situational and actionable attributes. This mechanism provides a critical theoretical bridge for explaining the matching effects between advertising message framing and appeal types.

Concrete information framing anchors consumers’ psychological distance at the individual utility level (low psychological distance) through quantified data and immediate benefit descriptions. In this context, competence-based appeals that emphasize instrumental rationality—the efficacy of solving concrete problems—align with the cognitive-processing patterns under low-level construal. Such congruence creates cognitive fluency matching by reducing information processing load [42], thereby enhancing consumers’ credibility assessments of advertising claims and strengthening purchase intentions. Conversely, abstract information framing extends psychological distance to the societal system level (high psychological distance) through symbolic narratives and delayed-value propositions. Warmth-based appeals highlighting communal belongingness and responsibility resonate with value-driven processing under high-level construal. CLT posits that, as the psychological distance increases, individuals increasingly rely on heuristics for decision-making [43]. Here, warmth appeals activate consumers’ prosocial self-concept, framing green consumption as an obligation to achieve attitude–behavior consistency.

Since warmth appeals and competence appeals influence consumer decision-making processes by stimulating emotional resonance and rational cognition, respectively, the design of information frameworks (such as concrete vs. abstract frames) can modulate how consumers process advertising information. Therefore, when the type of appeal and the information framework are highly matched, they may more effectively integrate consumers’ emotional and cognitive processing, thereby enhancing the overall communication effectiveness of the advertisement. Based on this reasoning, this study hypothesizes that the matching effect between warmth and competence appeals can not only significantly improve consumers’ attitudes toward the advertisement but also further increase their purchase intentions.

In summary, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

The degree of match between the advertising information framework and the advertising appeal will influence consumer responses;

H1a:

For concrete green advertising information, competence-based advertising appeals are more effective in promoting consumers’ positive responses to green products;

H1b:

For abstract green advertising information, warmth-based advertising appeals are more effective in promoting consumers’ positive responses to green products;

2.3. Moderating Role of Product Involvement

Consumer purchasing decisions are not simple buying behaviors but rather a complex systemic process that includes five stages: cognition, search, evaluation, purchase, and post-purchase evaluation. These stages are neither independent nor occur in a simple linear sequence. Due to the complexity of consumer decision-making, the process requires substantial time and effort, meaning that consumers need to be involved in the purchase process. According to consumer involvement theory, involvement is defined as “the degree to which an individual perceives an object as being related to their own needs, values, and interests” [44]. In simpler terms, involvement refers to the amount of time and effort consumers devote to searching for and processing information about products, as well as their conscious efforts to engage with product-related information and advertisements.

The degree of involvement is closely related to how events are perceived in relation to the individual. This connection is what defines involvement. Involvement varies in degree. Generally, products that require consumers to invest more time and effort to gather information in order to make a correct decision, such as digital cameras, cars, and insurance, are considered high-involvement products. In contrast, low-involvement products, such as everyday household items, require less effort from consumers to purchase. Typically, high-involvement products are more expensive, pose higher risks if purchased or used incorrectly, and are often durable goods that consumers do not purchase frequently. However, due to individual differences, consumer preferences for the same product can vary. High-involvement purchases typically trigger central route processing, where consumers systematically evaluate product attributes and functional benefits. Conversely, low-involvement purchases often rely on peripheral route processing, driven by heuristic cues like brand familiarity or emotional appeals. This dual-pathway mechanism underscores why message framing must align with involvement levels to optimize the persuasion efficacy [45].

Previous research has shown that product involvement positively affects the differentiation and integration of consumer information processing, as well as the frequency of purchases [46]. Therefore, product involvement influences consumers’ perceptions of brand image, which is presented through the brand’s advertising information. However, there is insufficient research on how product involvement moderates the matching effect between advertising framework and appeal.

This study argues that high product involvement often means that consumers are more likely to rationally analyze important product information, focusing on functionality and technical details. In such cases, a concrete framework and competence appeal are better aligned with consumer needs. On the other hand, low product involvement tends to evoke associations based on peripheral product information, making consumers more focused on emotional resonance and simplicity in advertisements. Thus, an abstract framework with a warmth appeal is more advantageous in these situations. Based on this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2:

The interactive effects of the green advertising information framework and advertising appeal on consumer responses are moderated by product involvement;

H2a:

When product involvement is high, the matching effect between concrete frames and competence perceptions will lead to the strongest purchase intention for green products, while the matching effect between abstract frames and warmth perceptions will no longer be significant;

H2b:

When product involvement is low, the matching effect between abstract frames and warmth perceptions will lead to the strongest purchase intention for green products, while the matching effect between concrete frames and competence perceptions will no longer be significant.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Advertising Attitudes

Advertising attitudes refer to consumers’ subjective evaluations of advertisements, encompassing both cognitive and affective responses (positive or negative). As a critical internal component of consumer responses, advertising attitudes directly shape purchase motivations [18]. Empirical evidence confirms a strong correlation between internal responses (e.g., brand identification) and external behaviors (e.g., purchase actions, word of mouth). Positive advertising attitudes correlate with heightened purchase intentions, whereas negative attitudes trigger brand aversion and decision avoidance [36].

Rooted in the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and Planned Behavior Theory (PBT), behavioral intentions are proximally determined by attitudes and subjective norms. In advertising contexts, this implies that consumers’ evaluations of ad content, design, and framing directly influence their willingness to act [47]. Notably, even green product claims exert indirect effects on purchase intentions through advertising attitudes [48]. Counter-intuitively, negative information—when perceived as more diagnostic—can reduce decision uncertainty and increase purchase certainty [49].

Building on this foundation, we posit that the congruence between advertising framing (concrete vs. abstract) and appeals (competence vs. warmth) operates through a dual-path mechanism. For the cognitive–affective pathway, matched framing–appeal pairings (e.g., concrete–competence) enhance the perceived ad credibility, fostering positive attitudes. For the behavioral activation pathway, these attitudes, in turn, amplify green purchase intentions.

Thus, we hypothesize:

H3:

Advertising attitudes mediate the effect of green advertising appeals and information framing on purchase intentions. Specifically, the congruence between concrete (vs. abstract) framing and competence (vs. warmth) appeals strengthens consumers’ advertising attitudes, thereby increasing their intention to purchase green products.

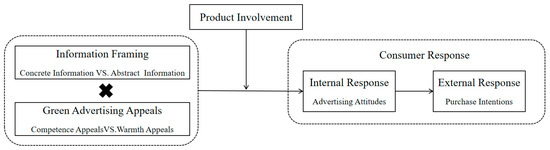

In summary, the theoretical framework is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework. Note: The cross symbol (×) denotes interaction effects between variables.

3. Experiment 1: Testing the Congruence Effect of Green Advertising Appeals and Information Framing

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

Prior to the main experiment, an independent pretest was conducted to validate the manipulation materials. Using G*Power 3.1, we determined a minimum sample size of 86 (α = 0.05, power = 0.8, effect size f = 0.25). A total of 162 participants were recruited via Credamo, with 18 invalid responses excluded (due to failed attention checks or completion times < 1.5 median absolute deviations), resulting in 144 valid responses (88.9% validity rate; 57.6% male). For the main experiment, we recruited 253 participants through the same platform. After excluding 14 invalid responses (inconsistent answers to reverse-coded items), 239 valid datasets were retained (94.5% validity rate). The sample comprised 46.4% female participants. Detailed demographic characteristics (e.g., education level, income tier, and environmental engagement frequency) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

3.2. Study Design

Experiment 1 aims to preliminarily validate how the congruence between advertising information framing (concrete vs. abstract) and appeals (warmth vs. competence) influences green product purchase intentions. In green consumption contexts, concrete advertising messages prime consumers to evaluate products based on utilitarian value and functional superiority, where purchase intentions are driven by competence perceptions (e.g., “Reduces 30% carbon emissions”). Conversely, abstract messages emphasize emotional value and societal impact, where warmth perceptions (e.g., “Protect the future, choose green”) dominate. We hypothesize that competence appeals will outperform warmth appeals in concrete framing conditions, while warmth appeals will excel in abstract framing conditions.

This study employed a 2 (message framing: concrete vs. abstract) × 2 (advertising appeal: warmth vs. competence) between-subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions via block randomization. To enhance task engagement, participants were informed of a nominal incentive (CNY 1) prior to the experiment. The procedure simulated a real-world consumer decision-making scenario, with instructions stating: “Imagine you are purchasing an air conditioner and encounter the following product advertisement online”. The participants then reviewed a green advertisement tailored to their assigned condition, adapted from authentic marketing campaigns. Following ad exposure, the participants completed sequential measures of psychological and behavioral variables, followed by demographic questions (age, gender, education, and income). The entire procedure was administered online, with the completion time restricted to 10 min to minimize fatigue effects.

3.3. Manipulation and Measures

3.3.1. Manipulation of Information Framing

Drawing on the Linguistic Category Model (LCM; Semin and Fiedler) [50], we operationalized two distinct message framing strategies. Concrete framing employed action-oriented verbs and quantifiable metrics to emphasize immediate, tangible outcomes (e.g., “Join your community to adopt energy-saving products, improving long-term health for families”). In contrast, abstract framing utilized adjective-driven narratives centered on values and broader ethical implications (e.g., “Choose eco-friendly products to ensure a prosperous, harmonious planet for future generations”). This approach aligns with LCM’s distinction between language that focuses on specific behaviors (concrete) and language that evokes generalized principles (abstract), ensuring a theoretically grounded manipulation of information specificity (see Appendix A).

3.3.2. Manipulation of Advertising Appeals

The warmth and competence appeals were operationalized based on the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; Fiske et al.) [11]. The warmth appeal emphasized community-oriented benefits through language prioritizing collective welfare (e.g., “Migre Energy-Efficient AC consumes 80% less energy and lasts 6x longer than conventional models. Our rigorous quality control ensures reliable, eco-conscious solutions for healthier families and communities”). In contrast, the competence appeal highlighted technical leadership and innovation using descriptors of expertise and achievement (e.g., “Migre’s vision is a sustainable Earth. Ranked among China’s top 3 in green innovation, we invest 0.1% of profits in reforestation, delivering cutting-edge eco-technology validated by 20 industry certifications”). This design ensured a clear distinction between warmth (ethical, communal focus) and competence (efficacy, technical superiority), aligning with the SCM’s theoretical framework.

3.3.3. Measures

All constructs were assessed using validated scales adapted to the green advertising context, with responses recorded on seven-point Likert scales (one = strongly disagree, seven = strongly agree). Concreteness perception was measured via a three-item semantic differential scale [13], capturing perceived message specificity, clarity, and claim certainty. Brand perceptions of warmth (e.g., generous, warm) and competence (e.g., efficient, capable) were evaluated using Aaker et al.’s [23] six-item scale, with three items per subdimension. Advertising attitudes were assessed using Campbell et al.’s [51] four-item scale, focusing on ad quality, appeal, and overall impression. Purchase intentions were operationalized through a three-item scale [14], addressing willingness to purchase, recommend, and prioritize the advertised product. To control for social desirability bias, a 10-item short form of the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale was included (e.g., “I always admit my mistakes”) [52]. The scale reliability was confirmed for all constructs (Cronbach’s α > 0.80).

3.4. Results

Regarding the advertising information framework, participants rated concrete ads as having a higher degree of specificity than abstract ads (M = 5.3842, SD = 0.8875 for concrete information vs. M = 4.7176, SD = 1.2430 for abstract information; F = 8.258, p = 0.005), confirming successful manipulation. For warmth and competence perceptions, the participants in the competence group rated the experimental materials as having a stronger sense of competence (M = 5.4306, SD = 0.8693 for competence perception vs. M = 2.3102, SD = 0.6995 for warmth perception; F = 5.076, p = 0.026), while the participants in the warmth group rated the experimental materials as warmer (M = 2.7222, SD = 1.0437 for competence perception vs. M = 5.6017, SD = 0.6679 for warmth perception; F = 5.348, p = 0.022).

The effect of the advertising information framework on consumer response was tested, but the advertising framework did not significantly influence purchase intention (M = 4.300, SD = 1.374 for concrete information vs. M = 4.224, SD = 1.402 for abstract information; F = 0.731, p = 0.393). Similarly, warmth and competence perceptions did not significantly affect purchase intention (M = 4.207, SD = 1.437 for competence perception vs. M = 4.315, SD = 1.338 for warmth perception; F = 3.124, p = 0.078).

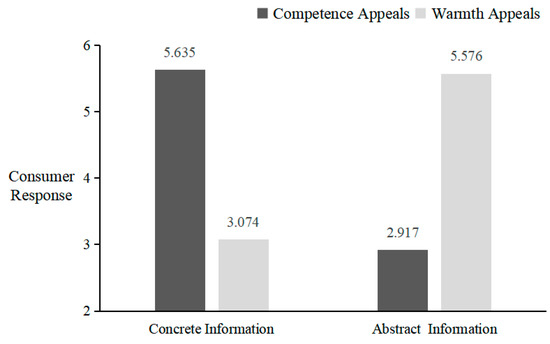

A two-way ANOVA was used to test the interaction between the advertising information framework and the green product perception on consumer response. The results showed that the interaction between the advertising information framework and the green product perception significantly affected consumer response (F(1,235) = 1927.860, p < 0.001), thus confirming H1. A simple effects analysis revealed that, under a concrete advertising framework, competence perception enhanced consumers’ purchase intention (M = 5.635, SD = 0.383 for competence perception vs. M = 3.074, SD = 0.568 for warmth perception; F(1,235) = 908.503, p < 0.001). Under an abstract advertising framework, warmth perception increased consumer response (M = 2.917, SD = 0.514 for competence perception vs. M = 5.576, SD = 0.319 for warmth perception; F(1,235) = 1022.505, p < 0.001). Both H1a and H1b were confirmed. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The interactive effect between advertising information framework and advertising appeals on consumer response.

Our findings align with the psychological distance theory [19], which posits that concrete framing enhances competence perceptions by emphasizing functional specificity (e.g., technical details, quantifiable benefits), while abstract framing amplifies warmth perceptions through aspirational narratives. The congruence between framing type (concrete/abstract) and perceptual dimension (competence/warmth) critically shapes advertising effectiveness. Concrete messages, by delineating precise usage scenarios or performance metrics (e.g., energy efficiency data), enable consumers to pragmatically evaluate a product’s reliability, thereby fostering trust in its utilitarian value. Conversely, abstract messages resonate emotionally by articulating macro-level goals (e.g., environmental stewardship, community welfare), which reinforce perceptions of the brand’s integrity. This dual mechanism underscores the necessity of tailoring advertising strategies to consumers’ psychological distance preferences. Concrete frameworks reduce cognitive ambiguity for competence-driven decisions, whereas abstract frameworks elevate symbolic value for warmth-oriented engagement. The match effect between product appeals and information framing is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The match effect between product appeals and information framing.

4. Experiment 2: Examining the Mediating Role of Advertising Attitudes and Moderating Role of Product Involvement

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

Based ona priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Cohen, 2013; α = 0.05, power = 0.8, effect size f = 0.25), a minimum sample of 232 participants was required. To account for potential exclusions, 580 participants were recruited via the Credamo platform. After removing 46 invalid responses (e.g., failed attention checks, incomplete responses), 534 valid cases were retained (48.4% male).

4.2. Study Design

To enhance the robustness and generalizability of the findings, Experiment 2 expanded the scope by recruiting a demographically diverse participant pool, increasing the sample size, and utilizing visual advertising stimuli. This experiment aimed to validate the mediating mechanism of advertising attitudes and the moderating effect of product involvement (H2 and H3), building on the foundational results of Experiment 1. A 2 (information framing: concrete vs. abstract) × 2 (advertising appeal: competence vs. warmth) × 2 (product involvement: high vs. low) between-subjects factorial design was implemented.

This study first conducted a pre-test on the manipulated materials through an independent verification process. After the manipulation check, new participants were recruited, and all were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions. The research staff informed the participants that they would receive a RMB 1 incentive upon completing the experiment as a token of appreciation, encouraging them to participate attentively.

The staff then introduced the experimental scenario to the participants: “Imagine you are in the market for a new electric vehicle (or a bottle of eco-friendly laundry detergent). While browsing online, you come across the following advertisement for an electric vehicle (eco-friendly laundry detergent). The advertisements and product descriptions differ across the eight experimental conditions, but all eight sets of advertisements were adapted from real-world ads”.

After participants read the scenario materials, they were asked to report their perceptions of the different advertisements, their attitudes toward the ads, and their green purchase intentions.

The product involvement scale was adapted from Zaichkowsky [53], which originally included 10 items measured on a seven-point scale. Since a longer questionnaire might cause participant fatigue, we shortened the scale to four items: whether the product is “important”, “relevant”, or “needed”, and whether it “involves” the participant. The measurement for advertising attitude and green purchase intention was the same as in Experiment 1.

4.3. Manipulation and Measures

4.3.1. Product Involvement Manipulation

Product involvement was operationalized by selecting two distinct product categories: electric vehicles (EVs) as high-involvement products and eco-friendly detergents as low-involvement products. Involvement levels were measured using a four-item semantic differential scale adapted from Zaichkowsky [53], which assessed perceived importance, relevance, necessity, and personal engagement (seven-point Likert scale). A pretest with 89 participants confirmed significant differences in the involvement scores between EVs (M = 5.53, SD = 0.58) and detergents (M = 3.00, SD = 0.75; p < 0.001), validating the categorization.

4.3.2. Manipulation of Information Framing and Advertising Appeals

For EVs, concrete framing emphasized quantifiable environmental benefits (e.g., “Reduces 40% emissions per kilometer and 42% lifecycle energy consumption”), while abstract framing highlighted aspirational values (e.g., “Drive with solar energy—embrace green living, protect our planet”). For eco-friendly detergents, concrete framing focused on tangible safety features (e.g., “Zero fluorescent additives, pH-neutral formula, 0 alkaline residue—safe for families”), whereas abstract framing underscored broader ecological commitments (e.g., “Carbon-neutral detergent: Gentle on hands, kind to nature, reduces water pollution”). To minimize brand familiarity biases, fictional brands (Weidi for EVs, Aobai for detergents) were created (see Appendix B).

Advertising appeals were visually manipulated following Zawisza and Pittard [24]. Competence appeals featured a male model in formal business attire (suit and tie) to convey technical expertise, while warmth appeals depicted a casually dressed male model (jeans and sweater) to evoke approachability and ethical alignment. All advertisements maintained a standardized layout: a headline at the top, descriptive text in the center, and product imagery in the lower section.

To ensure the validity of the multi-construct measurement model, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Constructs in the measurement model.

4.4. Results

Product involvement manipulation: The results of the manipulation check showed that the electric vehicle had a higher product involvement (M EV = 5.5276, SD = 0.5829), while the eco-friendly dishwashing liquid had a lower product involvement (M Dishwashing Liquid = 2.9980, SD = 0.7459). The pre-test confirmed the difference in involvement levels between the two products, which is appropriate for testing the influence of product involvement.

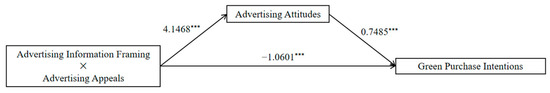

Using Model 8 in the PROCESS macro, with green purchase intention as the dependent variable and advertising attitude as the mediator, the mediation effect was tested at a 95% confidence interval. The results showed that advertising attitude played a mediating role (LLCI = 0.6767, ULCI = 0.8203, excluding 0). The path coefficient for the mediation effect is shown in Figure 3. Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 3.

The mediating effect of advertising attitude. Note: *** denotes statistical significance at p < 0.001.

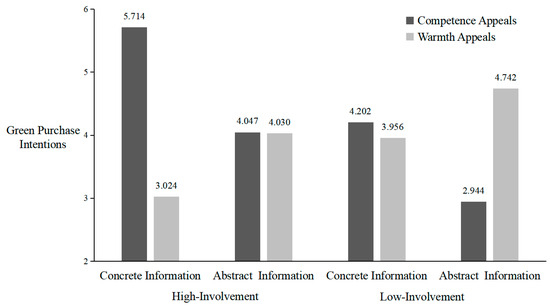

The three-way ANOVA results indicated a significant interaction among product involvement, green advertising information frame, and advertising appeal on green purchase intention (F(1, 526) = 5.525, p < 0.05). A simple effect analysis revealed that, for high-involvement products, using a concrete advertising frame with the ability appeal was more effective in triggering positive purchase intention than using the warmth appeal (M ability appeal = 5.714, SD = 0.521, M warmth appeal = 3.024, SD = 0.799, F(1, 277) = 660.44, p < 0.05). However, for high-involvement products with an abstract advertising frame, there was no significant difference in green purchase intention between the ability and warmth appeals (M ability appeal = 4.047, SD = 0.509, M warmth appeal = 4.030, SD = 0.611, F(1, 277) = 0.027, p > 0.05). For low-involvement products with an abstract advertising frame, the warmth appeal triggered a stronger purchase intention than the ability appeal (M ability appeal = 2.944, SD = 0.658, M warmth appeal = 4.742, SD = 1.448, F(1, 249) = 123.327, p < 0.05). For low-involvement products with a concrete advertising frame, there was no significant difference in green purchase intention between the ability and warmth appeals (M ability appeal = 4.202, SD = 0.458, M warmth appeal = 3.956, SD = 0.816, F(1, 249) = 2.299, p > 0.05). The detailed results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of product involvement on the interaction effect between advertising information framework and advertising appeals.

5. Discussion

The experimental results show that Hypothesis H2 and its sub-hypotheses, H2a and H2b, have been confirmed. Product involvement moderates the interaction effect between the green advertising information framework and advertising appeal. The moderating effect of product involvement on the match between advertising framework and appeal is significant, suggesting that consumers’ processing of advertisements is influenced not only by the content framework (concrete or abstract) and perception dimensions (ability or warmth) but also by the involvement level of the product.

Specifically, for high-involvement products (e.g., those closely related to consumers’ lives or requiring careful consideration), green purchase intention is strongest when a concrete advertising framework is matched with the ability perception, while the match between abstract information and warmth perception is no longer significant. High-involvement products typically involve a more complex decision-making process, and consumers tend to focus more on the actual utility and functionality of the product when purchasing such items. Therefore, concrete advertising is more effective in conveying the product’s specific advantages and features, enhancing consumers’ perception of the product’s capabilities. This suggests that, in high-involvement situations, consumers are more inclined to make rational decisions, focusing on the product’s actual performance and benefits, while the influence of warmth perception is relatively limited.

The attenuation of abstract–warmth matching effects under high product involvement can be further explained. When consumers face high-involvement decisions, they predominantly engage in central route processing, requiring detailed, evidence-based information to justify cognitive effort [45]. Concrete–competence matches align with this need by providing quantifiable benefits, which facilitate a systematic evaluation of product utility. In contrast, abstract–warmth appeals—reliant on symbolic narratives—may fail to satisfy the heightened demand for diagnostic information under high involvement, leading to reduced persuasiveness.

For low-involvement products (e.g., everyday consumables or impulse-purchase green products), green purchase intention is strongest when abstract advertising information is matched with warmth perception, while the effect of concrete advertising and ability perception is no longer significant. The decision-making process for low-involvement products is usually simpler, and consumers are more concerned with emotional resonance and quick decisions. Therefore, abstract advertising effectively conveys the emotional value of the product, triggering consumers’ warmth perception. In this case, the effect of concrete advertising on ability perception is no longer significant, possibly because consumers in such decision-making processes tend to focus more on emotions rather than specific functionalities and utility.

According to the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) [45], in low-involvement decision-making contexts, consumers tend to process information through the peripheral route, relying on emotional cues, heuristic rules, or superficial features for rapid judgments rather than systematically analyzing concrete functional attributes. In such situations, competence-based appeals in concrete advertisements require consumers to invest high cognitive resources to parse data and evaluate practical utility, which conflicts with their psychological need for decision-making efficiency in low-involvement purchases. Consequently, even if the advertising message is highly objective, its persuasive effectiveness may be undermined by cognitive miserliness.

It is important to acknowledge that, while abstract–warmth matches demonstrate efficacy in low-involvement contexts, their reliance on symbolic narratives introduces potential risks of perceived greenwashing. Consumers could doubt the authenticity of environmental claims due to insufficient verifiable evidence. This tension is particularly pronounced in low-involvement decisions, where heuristic processing may amplify skepticism toward vague promises [39]. For instance, abstract appeals emphasizing “sustainability” without concrete certifications could trigger skepticism [54], ultimately eroding green trust.

In summary, consumers are more rational in their purchase decisions for high-involvement products, where concrete advertising is better able to communicate the product’s specific functions and benefits, thereby enhancing purchase intention. In contrast, for low-involvement products, consumers are more focused on the brand’s emotional value, and abstract advertising effectively triggers their warmth perception, thus promoting purchase intention.

6. Conclusions

This study, based on the information framework theory and stereotype content model, explores the interaction effects of advertising information framework and advertising appeal on consumer response through two experiments and validates the mediating effect of advertising attitude and the moderating effect of product involvement.

The main conclusions are as follows.

First, Experiment 1 confirms the significant impact of the match between the advertising information framework and the advertising appeal on green product purchase intention. Specifically, the match between concrete framework and ability perception, as well as the match between abstract framework and warmth perception, both effectively enhance consumers’ purchase intention. Concrete advertising information, by providing specific details and contexts, helps consumers better perceive the product’s functions and utility, thus triggering a stronger sense of ability, especially regarding the perceived effectiveness of green products. This enhances consumers’ rational thinking and purchase motivation. On the other hand, abstract frameworks are better suited to match with warmth perception, as they convey grand societal goals and emotional values, thereby evoking emotional resonance, which in turn, promotes emotional identification and purchase intention for green products. The match between the advertising framework and perception dimensions not only increases consumers’ emotional resonance but also strengthens rational decision-making, further promoting green consumption behavior.

Experiment 2 further validates the moderating effect of product involvement in the interaction between advertising framework and advertising appeal and reveals that advertising attitude mediates the effect of advertising framework and appeal on green product purchase intention. In high-involvement situations, the matching effect between concrete framework and ability perception enhances consumers’ rational cognition of the product and their advertising attitude, which leads to more rational involvement and increases purchase intention. High-involvement products typically involve deeper emotional and value judgments, and concrete advertising information can convey the product’s effectiveness and real-life application through specific details, helping consumers better evaluate the product’s functionality, which in turn, stimulates stronger purchase motivation. In low-involvement situations, the match between abstract framework and warmth perception is more aligned with consumers’ need for quick processing of information, as it conveys the brand’s emotional value, thereby evoking emotional resonance and increasing purchase intention. Advertising attitude, as a mediating mechanism, plays a crucial role in explaining how the interaction between framework and perception influences consumers’ decision-making process through both emotional and cognitive pathways.

This study advances green advertising research through three key contributions. First, building on the framing effect theory, we propose a novel classification of advertising messages into concrete (e.g., quantifiable benefits) and abstract frameworks, addressing a gap in the prior literature focused on gain–loss or sales–inventory dichotomies. This classification underpins our discovery of the framing–appeal congruence effect: concrete messages paired with competence appeals and abstract messages with warmth appeals significantly enhance green purchase intentions, mediated by advertising attitudes. Second, we pioneer the application of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; Fiske et al.) [23] to advertising appeals, empirically validating warmth and competence as dual drivers of consumer responses. Third, we identify product involvement as a critical boundary condition: high-involvement products (e.g., electric vehicles) benefit from concrete–competence pairings, whereas low-involvement products (e.g., eco-friendly detergents) align with abstract–warmth strategies. These findings deepen the theoretical understanding of how cognitive and emotional mechanisms interact in sustainability communication.

The findings offer actionable strategies for optimizing green advertising campaigns. First, marketers should strategically align message framing with perceptual dimensions: concrete frameworks (e.g., quantifiable energy savings) paired with competence appeals (e.g., technical certifications) enhance credibility for functionally driven consumers, while abstract frameworks (e.g., ethical narratives) combined with warmth appeals (e.g., community welfare) resonate with emotionally oriented audiences. Second, product involvement dictates tactical priorities—high-involvement products (e.g., electric vehicles) benefit from emphasizing functional superiority through concrete details, whereas low-involvement products (e.g., eco-friendly packaging) require abstract storytelling to amplify symbolic value. Third, fostering positive advertising attitudes through emotional resonance (e.g., brand mission visuals) or rational persuasion (e.g., performance benchmarks) indirectly strengthens purchase intentions, underscoring the need for integrated cognitive–emotional messaging.

This study has four limitations. First, the reliance on fictional brands limits ecological validity; future research should test these mechanisms in real-world campaigns through field experiments. Second, product involvement was categorized broadly, neglecting individual-level variations. Future research could also explore the connections between hedonic versus utilitarian products, price, framing, and appeal. Third, while the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) explains the warmth–competence dynamics, societal shifts in environmental values may alter these perceptions over time. Longitudinal studies tracking evolving consumer stereotypes are needed to capture contextual nuances. These extensions would enhance the theoretical generalizability and practical relevance of the framework–appeal congruence model. Fourth, the exclusive use of Credamo-sourced participants—a Chinese online panel platform—introduces potential biases related to geodemographic homogeneity and self-selection effects. Although Credamo provides nationally representative quotas, its user base may systematically differ from offline consumer populations in environmental consciousness and brand engagement patterns. Future studies should validate these findings through multiplatform sampling and behavioral data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and Y.H.; methodology, J.Y. and Y.J.; software, J.Y. and Y.H.; validation, J.Y., Y.H. and X.S.; formal analysis, Y.J.; investigation, J.Y. and Y.J.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; supervision, X.S.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wuhan University of Technology on 15 March 2014. All participants provided informed consent, and the confidentiality of the data was strictly maintained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- (1)

- Participant Instructions—Thank you for participating in this academic survey. Your responses will remain anonymous and confidential. The survey will take approximately 2 min.

- (2)

- Informed Consent

“I confirm that I will answer all questions truthfully and to the best of my ability, reflecting my genuine intentions and behaviors”.

☑ I agree

☐ I decline

- (3)

- Screening Question

“Have you previously purchased or heard of green products (e.g., energy-efficient appliances, organic foods)?”

☑ Yes

☐ No

- (4)

- Experimental Scenario

“Imagine you are purchasing an air conditioner and encounter the following advertisement for Migre Energy-Efficient Green Air Conditioner”.

Concrete Framing Condition

Ad Copy:

“Join communities nationwide in adopting energy-saving appliances. Migre’s new green air conditioner reduces annual energy consumption by 80% compared to traditional models, with a lifespan six times longer. Rigorous quality control ensures reliable eco-friendly solutions”.

Measures:

1. ”How would you describe the ad content?” (1 = Abstract, 7 = Concrete)

2. ”How clear is the ad message?” (1 = Vague, 7 = Clear)

3. ”How certain are you about the ad’s claims?” (1 = Uncertain, 7 = Certain)

Abstract Framing Condition

Ad Copy:

“Choose Migre for a sustainable future. Our vision is a greener Earth—0.1% of profits fund global reforestation. Together, we protect tomorrow”.

Measures:

(Same as concrete framing condition.)

Warmth vs. Competence Appeals

Competence Appeal Condition

Ad Copy:

“Migre Energy-Efficient AC consumes 40% less energy and lasts twice as long as conventional models. Certified as an industry benchmark, we deliver unmatched technical excellence”.

Measures:

“This brand is generous/warm/friendly”. (Warmth)

“This brand is efficient/capable/effective”. (Competence)

Warmth Appeal Condition

Ad Copy:

“Migre’s mission: ‘A sustainable Earth for all.’ Ranked among China’s top 3 in green innovation, we invest in reforestation to nurture future generations”.

Measures:

(Same as competence appeal condition.)

- (5)

- Post-Experimental Questions

“Did you guess the purpose of this study?”

☑ Yes → “What do you think we were testing?” [Open response]

☐ No

- (6)

- Demographics

Gender: ☑ Male ☐ Female

Age: ☐ 0–20 ☐ 21–30 ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 ☐ 51–60 ☐ 60+

Education:

☐ Primary school ☐ Junior high ☐ Vocational/Technical school

☐ College ☐ Bachelor’s ☐ Master’s ☐ PhD

Occupation:

☐ Student ☐ State-owned enterprise ☐ Public institution

☐ Government ☐ Private firm ☐ Multinational corporation

Monthly Income:

☐ <300☐300☐300–700☐700☐700–1400☐1400☐1400–14,000☐>14,000☐>14,000

Appendix B

Figure A1.

New energy vehicle advertising: abstract–competence group.

Figure A2.

New energy vehicle advertising: abstract–warmth group.

Figure A3.

New energy vehicle advertising: concrete–competence group.

Figure A4.

New energy vehicle advertising: concrete–warmth group.

Figure A5.

Abstract–competence.

Figure A6.

Abstract–warmth.

Figure A7.

Concrete–competence.

Figure A8.

Concrete–warmth.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2021: The Heat Is on. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2021 (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Lima, P.; Falguera, F.P.S.; Silva, H.M.R.D.; Maciel, S.; Mariano, E.B.; Elgaaied-Gambier, L. From Green Advertising to Sustainable Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review through the Lens of Value-Belief-Norm Framework. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 53–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, S.; Milfeld, T. Sustainability Advertising: Literature Review and Framework for Future Research. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to Be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The sustainability liability: Potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. Positive and negative antecedents of purchasing eco-friendly products: A comparison between green and non-green consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Filieri, R.; Xiao, J.; Han, Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, T. Product Information and Green Consumption: An Integrated Perspective of Regulatory Focus, Self-Construal, and Temporal Distance. Inform. Manag. 2023, 60, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Xing, H.W.; Tian, H. Positioning the “Golden Quadrant” of Green Consumption: A Response Surface Analysis Based on the Stereotype Content Model. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 203–214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow from Perceived Status and Competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, G.; Lee, C.L.; Kota, S. Towards an Objective Evaluation of Alternate Designs. J. Mech. Des. 1994, 116, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, R.W.; Trudel, R.; White, K. Focusing on the Forest or the Trees: How Abstract versus Concrete Construal Level Predicts Responses to Eco-Friendly Products. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 57, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, J. The Impact of Perceived Online Review Credibility on Consumer Trust: The Moderating Role of Uncertainty Avoidance. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 146–159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dans, E.P.; González, P.A. The Unethical Enterprise of the Past: Lessons from the Collapse of Archaeological Heritage Management in Spain. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 172, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar Straus Giroux. 2011, 55, 915. [Google Scholar]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive consumer choice processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Ahmad, M. Impact of Cause-Related Marketing on Ad Credibility and Brand Attitude. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 11, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J.K.; Smalley, K.B.; Warren, J.C. The Impact of Cause-Related Marketing on Millennials’ Product Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 25, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.N.; Milne, A.B.; Bodenhausen, G.V. Stereotypes as Energy-Saving Devices: A Peek Inside the Cognitive Toolbox. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.; Vohs, K.D.; Mogilner, C. Nonprofits Are Seen as Warm and For-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawisza, M.; Pittard, C. When Do Warmth and Competence Sell Best? The “Golden Quadrant” Shifts as a Function of Congruity with the Product Type, Targets’ Individual Differences, and Advertising Appeal Type. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Leung, A.; Yan, R.N. It Is Nice to Be Important, But It Is More Important to Be Nice: Country-of-Origin’s Perceived Warmth in Product Failures. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervyn, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Malone, C. Brands as Intentional Agents Framework: How Perceived Intentions and Ability Can Map Brand Perception. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, E.; Lenoir, A.S.I.; Puntoni, S. Consumer Preference for Formal Address and Informal Address from Warm Brands and Competent Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Forming impressions of personality. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1946, 41, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, B.B. The serial position effect of free recall. J. Exp. Psychol. 1962, 64, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugtvedt, C.P.; Wegener, D.T. Message order effects in persuasion: An attitude strength perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivio, A. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Conder, J.A.; Blitzer, D.N.; Shinkareva, S.V. Neural representation of abstract and concrete concepts: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010, 31, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, F.; Seo, Y.; Li, L.P.; Shi, L. Awe in Advertising: The Mediating Role of an Abstract Mindset. J. Advert. 2021, 52, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Strategies for Environmental Advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 1993, 10, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Rehman, V. Negative Emotions in Consumer Brand Relationship: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 719–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishen, A.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Bindu, N.; Kumar, K.S. A Broad Overview of Interactive Digital Marketing: A Bibliometric Network Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Yim, Y.C.; Kim, E.A.; Reeves, W. Exploring the Optimized Social Advertising Strategy That Can Generate Consumer Engagement with Green Messages on Social Media. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, A.K.; Weber, A. Can You Believe It? The Effects of Benefit Type versus Construal Level on Advertisement Credibility and Purchase Intention for Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neureiter, A.; Stubenvoll, M. Is It Greenwashing? Environmental Compensation Claims in Advertising, Perceived Greenwashing, Political Consumerism, and Brand Outcomes. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Menon, G. Concrete vs. Abstract Thinking: The Role of Message Framing in Promoting Sustainable Consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Aaker, J.L. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KöRner, A.; Volk, S. Concrete and abstract ways to deontology: Cognitive capacity moderates construal level effects on moral judgments. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 55, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Volume 19, pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.H.; Han, I. The effect of negative online consumer reviews on product attitude: An information processing view. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 7, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and Bluewashing in Black Friday-Related Sustainable Fashion Marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. The Harassed Decision Maker: Time Pressures, Distractions, and the Use of Evidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Sun, K.; Long, R. Navigating Sentiment Dynamics in Social Media: The Role of Information Characteristics in Promoting Green Consumption across Multiple Domains. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semin, G.R.; Fiedler, K. The Linguistic Category Model, Its Bases, Applications and Range. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 2, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C.; Lane, K.K. Brand Familiarity and Advertising Repetition Effects. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.G.; Fick, C. Measuring Social Desirability: Short Forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Research Notes: The Personal Involvement Inventory: Reduction, Revision, and Application to Advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Berman, J.Z.; Reed, A. Tip of the hat, wag of the finger: How moral decoupling enables consumers to admire and admonish. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).