Abstract

Femvertising is increasingly being used by brands to showcase their values and attract consumers, especially in the fashion industry. Previous studies mainly focused on its impact on female consumers, while the perceptions and responses of male consumers are usually ignored. Focusing on the context of men purchasing women’s clothes as gifts, this study aimed to explore the impact of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention and reveal the mechanism, with the mediating effects of female empowerment and brand hypocrisy and the moderation effect of gift recipient. A situational experiment was conducted to acquire data, and hypotheses were tested with regression analysis and the bootstrapping method. The results demonstrated that the total effect of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention is not significant, but there is a positive mediating effect of female empowerment and a negative mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, and the mediating effect of female empowerment is stronger for a communal relationship (versus an exchange relationship).

1. Introduction

The feminist movement has profoundly changed the world, and commercial advertisements also play an important role in it [1,2]. In the era of e-commerce, brands are shifting from product-centered marketing strategies toward consumer-centered marketing strategies, and femvertising is one of the most popular tactics [3,4]. Femvertising, as an emerging form of advertising, aims to empower women by showcasing women’s social dilemmas, challenging traditional gender stereotypes, and advocating for women’s rights [5,6]. Brands now frequently use femvertising with the aim of enhancing brand image and promoting sales performance, especially in China, where women are traditionally considered inferior to men and are bound by many social stereotypes [3,7]. Luckily, China’s economy and society have undergone tremendous changes in the past several decades, and the younger generation, both men and women, have started to show more concern about gender issues than the older generations [8]. As feminism is a hot topic of public concern, especially on social media, femvertising is likely to spark widespread discussion and attract a large amount of attention. It has been found by many studies that femvertising enhances brand awareness, brand reputation, brand loyalty, and ultimately the purchase intention of consumers [9,10,11]. However, it is also questioned as a new form of greenwashing, also known as femwashing, which uses feminism as a commercial tool to trap consumers, lacking an in-depth exploration of substantive issues of women’s empowerment [12]. Some advertisements oversimplify women’s social dilemmas and attribute them solely to gender inequality, while neglecting gender differences and individual diversity, thereby exacerbating gender conflicts [13]. Some feminist advertisements are essentially consumption traps, bundling gender issues with product promotions, which undermines their significance for social change [14]. Additionally, some femvertising claims disregard cross-cultural contexts, such as the unique perspectives of Chinese culture, leading to widespread controversy, especially among male consumers [15,16]. However, previous research on femvertising has mostly focused on its positive impact on female consumers [17,18], while male consumers’ perceptions, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors may be more complex and warrant further investigation [19,20].

It is crucial for brands to carefully evaluate public perceptions and reactions before using femvertising to avoid criticism or resistance. Advertisements are usually public for everyone, even if they are not targeting consumers of both genders. Male consumers’ perceptions of femvertising may be quite different from that of female consumers because of various factors such as gender identity, social norms, and personal beliefs [15]. They may even view femvertising as an attack on men and respond with a defensive mentality [18]. Even if the products in the advertisement are not meant for men, they may also make negative comments and engage in debates with women online. These online disputes are widely spread and may damage a brand’s social image and reputation. Furthermore, a large portion of fashion products designed for women are purchased by male consumers as gifts to women. In China, men buying gifts for women is a common practice, especially during holidays, birthdays, and romantic occasions [21,22]. Gift giving is seen as a gesture of affection, status, and social etiquette, driving demand for high-end cosmetics, jewelry, handbags, and perfumes [23,24]. In response, brands often target male consumers with gender-specific campaigns, making male-driven gifting a key revenue stream in China’s fashion market. Male consumers are never bystanders or outsiders in the field of femvertising, and neglecting their reactions hinders the effectiveness of femvertising and exacerbates conflicts between men and women [20,25].

Focusing on the context of men purchasing women’s clothes as gifts, this study explores the impact of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention and revealed the mechanism, with the mediating effects of female empowerment and brand hypocrisy and the moderation effect of gift recipient. It contributes to the theory in the following four aspects: First, it extends the theories of femvertising from the perspective of male consumers, which is quite different from that of female consumers. Even though it focuses on the context of gift giving, the distinct perceptions of female empowerment and brand hypocrisy are also inspiring in understanding and predicting their responses in self-purchasing. Second, this study has found a positive mediating effect of female empowerment and a negative mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, which provide a more comprehensive mechanism to explain the consequences of femvertising. Third, it has also found a moderating effect of gift recipient, which helps to clarify the contextual differences in the consequences of femvertising. Fourth, a situational experiment has been conducted to strengthen the causality in the conclusions, which may inspire experimental designs in future studies on femvertising. By revealing the dual effects of femvertising on male consumers, this study wishes to inspire brands to better use femvertising to promote their brand image and sales performance. It also wishes to guide male consumers to participate more actively in gender equality campaigns, eliminate gender bias, cultivate social respect for individual autonomy, and promote social harmony on the Internet.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Femvertising on Female Empowerment

Advertisements convey not only specific information such as brand names and product features, but also abstract information such as the brand’s missions, visions, and values. Brands are now increasingly using advertisements to articulate their attitudes and beliefs about social issues, especially gender equality [2,20]. Femvertising aims to empower women by breaking traditional gender stereotypes through positive and inclusive communication [3,26]. In addition to directly advocating for women’s rights, brands usually use diverse, including imperfect, female images in their advertisements to encourage women to accept their true selves [27,28,29]. For example, Dove’s “Real Beauty Campaign” challenges traditional body standards by showcasing women of different ages, body types, and races. Brands also resonate with female consumers by depicting the social dilemmas faced by women, prompting audiences, including male audiences, to think from a female perspective [30,31]. For example, Procter & Gamble’s “Like a Girl” advertisement reflects on gender stereotypes by showcasing the stigmatization of behaviors such as running and fighting in girls. Brands can also depict confident and independent women participating in activities that are traditionally considered male privileges to encourage women to pursue their dreams and support each other [3,32]. For example, Nike’s “Dream Crazier” advertisement inspires women to be brave and independent by telling stories of female athletes overcoming difficulties and pursuing their dreams.

With these advertisements, brands wish to encourage women to achieve self-acceptance, self-respect, self-actualization, and self-empowerment. Female empowerment is the idea of inspiring women to be independent and take responsibility for their own identity and choices [33]. It concerns not only high access to resources, but also a strong mentality to pursue their own goals [34]. Individuals with low psychological empowerment are very likely to fail due to a lack of goals, self-efficacy, and motivation [35]. Because of gender inequality and stereotypes, many women are not brave enough to be independent and pursue their own dreams, such as a successful career. Some of them are even dissatisfied with their own body and become depressed when others criticize their appearance or weight. Femvertising links female empowerment with the brand, making women feel more confident, independent, and powerful when using their products [2,36]. Traditional advertisements often focus on product features and do not involve women’s body aesthetics, social dilemmas, and equality issues, which implies little impact on male consumers’ perception of female empowerment [15,20]. Some advertisements even deliberately promote women’s perfect body shape, emphasize women’s role in the family, and advocate that women are inferior to men [30]. These advertisements cater to male consumers’ gender stereotypes and reduce their perception of female empowerment. In contrast, although the diverse female images in femvertising challenge male consumers’ aesthetic standards, they also encourage men to embrace a broader range of aesthetic concepts [27,29]. They may inspire men to realize that women are not only their aesthetic objects, but also vivid and independent individuals. More importantly, men may have become accustomed to the injustices faced by women in their daily lives, but seeing the suffering of women may prompt them to realize the harm of gender inequality, start to reflect on their own gender bias, and gain a better understanding of female empowerment [31,37,38]. Moreover, seeing successful female role models in advertisements provides a positive psychological cue that women can achieve everything and anything that they set their mind to [32]. Male consumers can also see what women can achieve when given the opportunity and start to believe in the potential of liberating women. When brands sincerely showcase their efforts in addressing gender equality issues, men will believe that femvertising is the right way to promote female empowerment [19,20]. Therefore, femvertising is likely to generate a perception of female empowerment in male consumers, leading to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

H1.

Femvertising (versus traditional advertising) will be associated with higher female empowerment by male consumers.

2.2. The Impact of Femvertising on Brand Hypocrisy

As consumers become acquainted with femvertising, especially on social media, they become increasingly concerned about the authenticity of these advertisements [39]. Consumers start to realize the disconnect between brand claims and their actual behaviors, and question their motivations [40]. Brand hypocrisy is the perception that a brand claims to be something it is not, especially regarding the brand’s missions, visions, and values [41]. By making vague promises or excessive statements about their accomplishments, brands wish to benefit from an undeserved perfect image [42,43]. In the case of femvertising, supporting women’s rights is socially desirable and can bring positive Word-of-Mouth [37,39]. Therefore, many brands aspire to be seen as women-friendly and use femvertising as a tool to promote their brand image and sales performance [1,6]. However, despite the popularity of femvertising, few brands have actually taken concrete actions to address women’s social dilemmas [12,14]. Femvertising improves a brand’s image only when consumers believe that the brand is authentic and putting in effort to address gender inequality problems [37,44]. Male consumers may respond positively to brands that they believe truly support gender equality, but they are also very skeptical of femvertising [20]. Men are in an advantageous position in gender relations and are inclined to stick to traditional gender norms to maintain their status [19,20]. They usually defend traditional gender stereotypes by attributing them to gender differences and denying the injustices faced by women. With such a defensive mentality, male consumers are likely to criticize brands for just using femvertising as a promotional tool instead of an authentic strategy [13]. Common techniques of femvertising, such as showcasing diverse female images, gender stereotypes, and female role models, are likely to be questioned as just empty talk without concrete evidence of specific activities to support their claims [14,25]. Consumers will argue that brands should have conducted an in-depth exploration of substantive efforts to promote the actual development of women [38,39]. In addition, some feminist advertisements have gone too far and seem inauthentic. For example, to alleviate women’s body anxiety, some advertisements use models with imperfect figures, but in the eyes of men, they are considered unattractive and self-deceiving. Even worse, some brands deliberately intensify gender conflicts and create topics to attract public attention on social media, which may also be seen as inauthentic [12,13]. Therefore, femvertising is likely to result in a perception of brand hypocrisy in male consumers, leading to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

H2.

Femvertising (versus traditional advertising) will be associated with higher brand hypocrisy by male consumers.

2.3. The Impact of Female Empowerment on Gift Purchasing Intention

It has been found by many studies that female empowerment stimulates positive emotional feedback from female audiences and strengthens the psychological bond with female consumers [45,46]. Exposure to empowering media promotes self-efficacy and encourages female consumers to take action to achieve their goals [47,48]. A general feeling of empowerment is even beneficial to female’s subjective well-being [34]. However, it is still unclear how male consumers respond to female empowerment, especially in the context of gift giving. Interpersonal relationships are essential, and gifts are often given to cultivate these relationships in China, where individual interactions are influenced by unique local culture such as “Guanxi (social connections)”, “Mianzi (face)”, and “favors” [21,49]. Gift giving has significant social, well-being, and economic consequences [50], while inappropriate gifts can lead to negative outcomes [51,52]. Choosing gifts is subject to various factors, including the givers’ motives, receivers’ preferences, and social norms [53]. Gifts not only provide functional value for the receivers, but also carry the intention of the givers to showcase their own values, strengthen social connections, and promote interpersonal relationships [51]. Inappropriate gifts may embarrass the receiver, create an identity threat, and even damage relationships [52,54]. Gift givers are extremely cautious when choosing a gift, especially men, given that they are usually not very familiar with fashion products for women [50]. Instead of focusing on the characteristics and cost-effectiveness of the product, male consumers may pay more attention to the symbolic meaning of the brand. Female empowerment has become a widely recognized social trend, and women are likely to feel respected when they receive gifts that empower women [4,28]. For male consumers who sincerely endorse feminism, female empowerment is likely to promote favorable attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand [45,55]. They will choose the brand with the expectation that the gift will make the recipient more confident, independent, and free. Although many men may not genuinely approve of female empowerment, few will openly disparage it and conflict with women [20]. Choosing a gift that empowers women can also help men to convey a positive impression to their female friends by expressing respect for women and care for them. Therefore, female empowerment is likely to promote male consumers’ gift purchasing intention, leading to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

H3.

Female empowerment will be positively associated with male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

Considering that femvertising facilitates female empowerment and female empowerment promotes male consumers’ gift purchasing intention, it is reasonable to propose that there is a positive mediating effect of female empowerment in the relationship between femvertising and gift purchasing intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

There is a positive mediating effect of female empowerment in the relationship between femvertising and male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

2.4. The Impact of Brand Hypocrisy on Gift Purchasing Intention

It has been demonstrated by many studies that brand hypocrisy damages brand reputation [44], the customer–brand relationship [56], Word-of-Mouth [57], and ultimately results in brand switching intention [43]. Compared to in self-purchasing, gift givers place particular emphasis on the brand image of the gift, as they hope that giving the gift will help them gain a better personal imager [22]. Gifts not only reflect the givers’ taste but also imply how much they care about the relationship [54]. In purchasing a fashion gift for female friends, male consumers usually select brands that are well known, reputable, and undisputed [51,57]. If a brand is insincere about its claims in femvertising, it is likely to cause a lot of controversy, making it a risky brand for gift giving. In addition, even though the gifts are not for their own use, gift givers also tend to purchase a brand that they like [50]. Brand hypocrisy usually results in negative effects on brand trust, credibility, and authenticity, which in turn lower consumers’ commitment and loyalty toward the brand [39,58]. A perception of hypocrisy also leads consumers to question the brand’s ethical standards [59,60]. A hypocritical brand with low ethical standards is likely to do anything for the sake of profit, which implies high risks not only in claims about feminism but also in information about product features [41,61]. Disappointed consumers are likely to spread negative Word-of-Mouth about the product instead of choosing it as a gift for their female friends [43,62]. Therefore, brand hypocrisy is likely to hinder male consumers’ gift purchasing intention, leading to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

H5.

Brand hypocrisy will be negatively associated with male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

Considering that femvertising results in brand hypocrisy and brand hypocrisy hinders male consumers’ gift purchasing intention, it is reasonable to propose that there is a negative mediating effect of female empowerment in the relationship between femvertising and gift purchasing intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H6.

There is a negative mediating effect of brand hypocrisy in the relationship between femvertising and male consumers’ gift purchasing intention.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Gift Recipients

Gift choices are determined not only by the characteristics of the gifts, but also by the nature of the relationship between the giver and the receiver [63,64]. Two basic types of interpersonal relationship have been identified, namely, an exchange relationship and a communal relationship [65,66]. An exchange relationship is common in interpersonal interactions, especially among colleagues and business partners. It is usually established based on cooperation and common interests, where individuals expect equivalent or corresponding returns when providing resources or support [67,68]. It is characterized by strong reciprocity, weak emotional bonds, and short-term orientation [68,69]. In comparison, a communal relationship often develops among family members and close friends. It emphasizes unconditional care and support of each other, with individuals aiming for each other’s well-being rather than seeking direct returns [67]. It is characterized by strong altruism, emotional bonds, and long-term orientation [68,70]. Of course, an exchange relationship may also develop and transform into a communal relationship in certain circumstances.

In selecting a gift, givers usually adjust their focus based on the closeness of their relationship with the recipient [49,71]. The closer the relationship, the more the gift giver values the experiential benefits of the gift—otherwise, the more they value the functional benefits of the gift [72]. People in a communal relationship are usually more intimate than people in an exchange relationship [67]. In communal relationships, people look out for each other’s needs and show genuine concern for each other’s welfare [56,57]. Female empowerment provides rich experiential benefits through emotional resonance, uniqueness, self-identity, and social influence [1,10]. When male consumers are picking a gift for female friends in a communal relationship, they are more concerned about the recipients’ personal growth and control over their identity [32,51,66]. In this case, male consumers are likely to place more emphasis on female empowerment, which implies a stronger effect of female empowerment on their gift purchasing intention [20,33]. In contrast, in exchange relationships, people place more emphasis on the equivalence of paying and receiving instead of each other’s welfare [68,69]. When male consumers are picking a gift for female friends in an exchange relationship, they are more concerned about whether the value of the gift can be recognized and repaid in a comparable manner [65]. They may rely more on superficial cues, such as product features and price, overlooking the deeper messages of female empowerment. In this case, male consumers are likely to place less emphasis on female empowerment, which implies a weaker effect of female empowerment on their gift purchasing intention. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H7.

The positive effect of female empowerment on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention is stronger when the gift recipient is in a communal relationship (versus exchange relationship).

As discussed earlier, brand hypocrisy hinders male consumers’ gift purchasing intention mainly because of poorer brand reputation, weaker brand commitment, and higher risks in the products [44,56,60]. Regardless of whether they are picking a gift for a female friend in a communal relationship or in an exchange relationship, a good brand reputation, strong brand commitment, and low risks in the products are always important. Therefore, the effect of brand hypocrisy on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention is likely to be similar for the two kinds of gift recipients, leading to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

H8.

The negative effect of brand hypocrisy on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention will not be moderated by gift recipients.

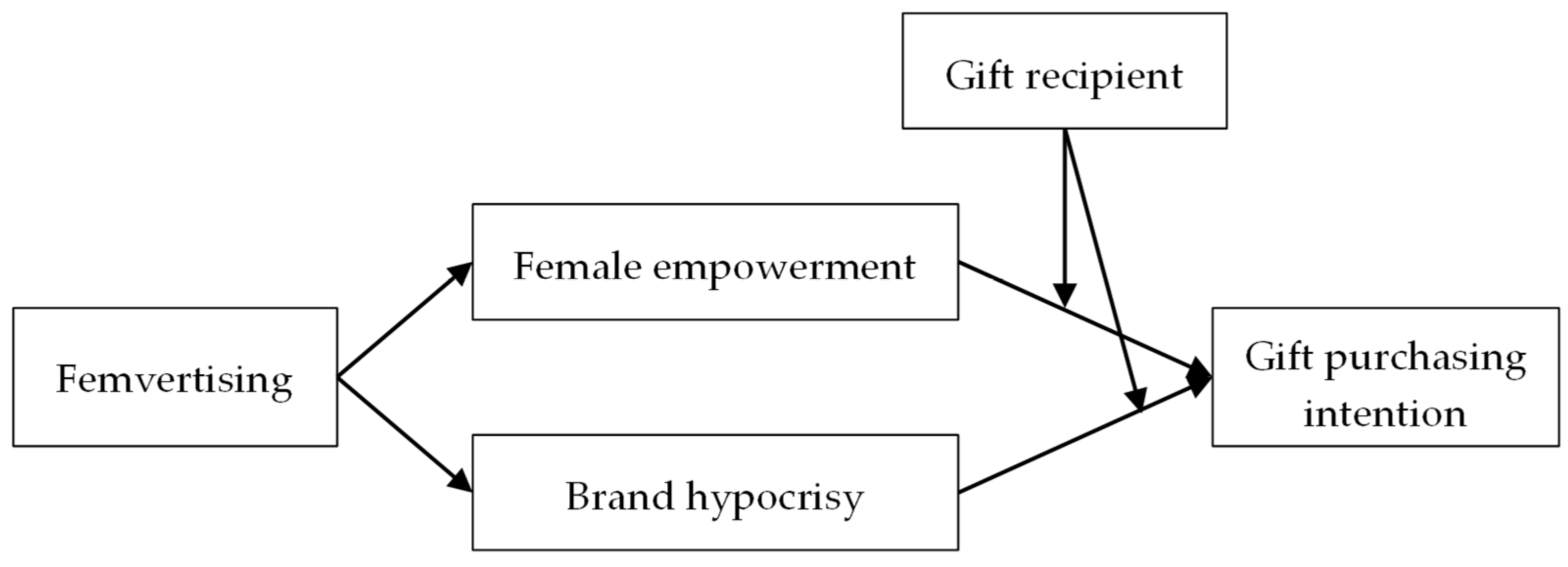

The theoretical framework and hypotheses are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Materials

A situational experiment was conducted in China to acquire data for testing the hypotheses. Compared with other methods, like questionnaire surveys, for example, situational experiments are advantageous in manipulating the variables to reduce common method bias and strengthen the causality in the results. They can also avoid interference from real brands and advertisements, as if consumers know the brand beforehand, their purchasing intention could be influenced by many other factors besides femvertising. The independent variable femvertising and the moderating variable gift recipient were manipulated with materials including images and texts. In addition, to enrich the diversity of materials, two sets of clothes were used, including a dress and a submachine jacket. Following the idea of an orthogonal experiment, 8 sets of experimental materials were designed: 2 (traditional advertising vs. femvertising) × 2 (exchange relationship vs. communal relationship) × 2 (dress vs. jacket). The materials were coded with 3 digits: traditional advertising was coded as 0, and femvertising was coded as 1; an exchange relationship was coded as 0, and a communal relationship was coded as 1; and the dress was coded as 0, and the jacket was coded as 1. Advertisement type was manipulated through text, with traditional advertising emphasizing product features while femvertising emphasized breaking stereotypes about women’s individual autonomy. Gift recipient was manipulated by asking the participants to think of a female friend of a certain kind and answer the questionnaire accordingly. The experimental materials are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental materials.

3.2. Participants and Procedure

The experiment was carried out with an online questionnaire. The 8 experimental materials were inserted at the beginning of the questionnaire, with a random button to randomly assign participants to one of the eight groups. Convenience sampling was used, because the subjects of this study were all male consumers and it was not possible to obtain a population list to implement random sampling or stratified random sampling. To reduce potential sampling bias, the experiment was conducted on a crowdsourcing survey platform SoJump to acquire various samples. It is suggested that sample size should be five times more than the numbers of items, and there should be more than 30 samples for each group in situational experiments [73]. There are 9 items in the questionnaire and 8 groups in the experiment, so there should be at least 240 samples for this study. A total of 445 participants were recruited and assigned to the 8 groups randomly. The participants read the experimental materials and answered the questionnaire independently. After deleting 21 unqualified participants (those with most items rated at the same scores or rated in a clear pattern), 424 valid participants were obtained (effective response rate was 95.3%). Most of the participants were aged from 26 to 40 (69.1%), had a bachelor’s degree (76.7%), and had a monthly income between CNY 5001 and 15,000 (51.6%). Moreover, based on the sample distribution of the 8 groups, the sample sizes for traditional advertising and femvertising were 217 and 207, the sample sizes for an exchange relationship and a communal relationship were 200 and 224, and the sample sizes of for the dress and the jacket were 224 and 200, which were relatively even and acceptable. Demographic descriptions of the participants are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic statistics.

3.3. Measurement Scales

Apart from the variables manipulated by experimental materials, the mediating variables female empowerment and brand hypocrisy and the dependent variable gift purchasing intention were measured with Linkert scales ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree.

Female empowerment. Female empowerment was measured with a scale adapted from Teng et al. [15]. The three items were “The woman in the advertisement is powerful”, “The woman in the advertisement is independent”, and “The woman in the advertisement has a lot of control”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Brand hypocrisy. Brand hypocrisy was measured with the scale from Wagner et al. [41]. The three items were “This brand acts hypocritically”, “What this brand says and does are two different things”, and “This brand pretends to be something it is not”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

Gift purchasing intention. Gift purchasing intention was measured with a scale adapted from Barta et al. [74]. The three items were “I am very likely to purchase the clothing as a gift”, “I intend to purchase the clothing as a gift”, and “I will purchase the clothing as a gift”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Control variables. Age, education, income, and clothing were chosen as control variables.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validation

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the validity issues. The results of model comparison are presented in Table 3. The results indicate that the hypothesized three-factor model has the best fit with the data, so it will be used for further analysis.

Table 3.

Results of model comparison.

The results of validity analysis are presented in Table 4. The results indicated that all the standardized regression weights (λ) were larger than 0.7, all the composite reliability (CR) values were larger than 0.8, and all the average variance extracted (AVE) values were larger than 0.5, which indicated that the convergent validity was acceptable. In addition, as reported earlier, the Cronbach’s alphas of all variables were larger than 0.8, which indicated that the internal validities were also acceptable. In addition, as presented in Table 5, the square roots of AVE were all larger than the correlations between corresponding variables, which indicated that the discriminant validity was also acceptable.

Table 4.

Results of validity analysis.

Table 5.

Results of correlation analysis.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

The results of correlation analysis are reported in Table 5. Femvertising positively correlated with female empowerment (r = 0.189, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with brand hypocrisy (r = 0.277, p < 0.01). Female empowerment positively correlated with gift purchasing intention (r = 0.463, p < 0.01), while brand hypocrisy negatively correlated with gift purchasing intention (r = −0.714, p <0.01). In addition, femvertising was not significantly correlated with gift purchasing intention (r = 0.091, p > 0.05).

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

The hypotheses were tested with regression analysis and the bootstrapping method using PROCESS v4.2 in SPSS 26.0. The bootstrapping sample size was set as 5000 to calculate the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All variables had been standardized before the regression analysis. The results are summarized in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 6.

Results of regression analysis.

Table 7.

Results of mediating effect analysis.

Table 8.

Results of moderated mediating effect analysis.

As reported in Table 6, femvertising positively affects female empowerment (Model 1, b = 0.193, p < 0.001), which supports hypothesis H1. Femvertising also positively affects brand hypocrisy (Model 2, b = 0.269, p < 0.001), which supports hypothesis H2. Furthermore, female empowerment positively affects gift purchasing intention (Model 4, b = 0.245, p < 0.001), while brand hypocrisy negatively affects gift purchasing intention (Model 4, b = −0.647, p < 0.001), which supports both hypothesis H3 and H5.

As reported in Table 7, the indirect effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention through female empowerment was significant (b = 0.047, 95% CI [0.022, 0.077] excluded zero), which supports hypothesis H4. The indirect effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention through brand hypocrisy was also significant (b = −0.174, 95% CI [−0.243, −0.107] excluded zero), which supports hypothesis H6. Additionally, the total effect of femvertising on gift purchasing intention was not significant (b = −0.085, 95% CI [−0.179, 0.010] included zero). These results indicate that femvertising promotes male consumers’ gift purchasing intention through female empowerment and hinders their gift purchasing intention through brand hypocrisy at the same time.

As reported in Table 6, the regression coefficient of the interaction of female empowerment and gift recipient in gift purchasing intention was positive and significant (Model 5, b = 0.263, p < 0.001). To be more specific, as reported in Table 8, the effect of female empowerment on gift purchasing intention was −0.138 when the gift recipient was in an exchange relationship and changed to 0.388 when the gift recipient was in a communal relationship. The intergroup difference was 0.526, and the 95% CI [0.378, 0.672] excluded zero. Therefore, the intergroup difference was significant, which supports hypothesis H7. In addition, the mediating effect of female empowerment was −0.027 for an exchange relationship and 0.075 for a communal relationship, the intergroup difference was 0.101, and the 95% CI [0.050, 0.160] excluded zero. Therefore, the moderated mediating effect was also significant.

Meanwhile, as reported in Table 6, the regression coefficient of the interaction of brand hypocrisy and gift recipient in gift purchasing intention was not significant (Model 5, b = 0.017, p > 0.05). To be more specific, as reported in Table 8, the effect of brand hypocrisy on gift purchasing intention was −0.608 when the gift recipient was in an exchange relationship and changed to −0.574 when the gift recipient was in a communal relationship. The intergroup difference was 0.034, and the 95% CI [−0.096, 0.164] included zero. Therefore, the intergroup difference was not significant, which supports hypothesis H8. In addition, the mediating effect of brand hypocrisy was −0.163 for an exchange relationship and−0.154 for a communal relationship, the intergroup difference was 0.009, and the 95% CI [−0.034, 0.052] included zero. Therefore, the moderated mediating effect was not significant.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study aimed to explore the impact and mechanism of femvertising in male consumers’ gift purchasing intention. The results demonstrated that the total effect of femvertising on male consumers’ gift purchasing intention is not significant, but there is a positive mediating effect of female empowerment and a negative mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, and the mediating effect of female empowerment is stronger for a communal relationship (versus an exchange relationship). This study has made four theoretical contributions. First, previous studies mainly focused on the impact of femvertising on female consumers [19,20], while this study has explored the perceptions and responses of male consumers, which has enriched theories of the consequences of femvertising. Meanwhile, most previous studies were conducted from the perspective of self-purchasing [3,17], while this study was conducted from the perspective of gift giving, which is helpful to provide more distinct insights to understand consumer perceptions and behaviors. Second, it has demonstrated the positive mediating effect of female empowerment and the negative mediating effect of brand hypocrisy, which are original and provide a more comprehensive mechanism to explain the dual effects of femvertising rather than just emphasizing its positive effects [12,14]. Third, focusing on the context of gift giving, this study has also demonstrated the moderating effect of gift recipient, which helps to clarify the contextual differences in the impact of femvertising and illuminate its theoretical boundaries. Fourth, most previous studies relied on quantitative methods such as questionnaire surveys to study femvertising [5,35], with some other studies using qualitative and inductive methods [16,38], while this study has conducted a situational experiment to acquire data for hypothesis testing. This helps to strengthen the causality in the conclusions and makes a modest methodological contribution in inspiring experimental designs in future studies on femvertising.

5.2. Practical Implications

Several practical implications can be derived from these findings. First, brands should actively explore femvertising, depicting women in an equal, independent, strong, and diverse manner to convey female empowerment. Second, femvertising should stimulate better dialogue between men and women, instead of triggering fierce criticism and resistance from male consumers. Brands should adhere to the concept of gender equality rather than being too radical or biased. They should also carefully evaluate the potential responses of the public, including male and female members, before releasing advertisements. Third, brands can contingently choose femvertising or not choose it, based on their products and target markets. For example, femvertising is more effective for products that are meant for gift recipients in communal relationships and products specially designed for certain celebrations such as Valentine’s Day or Mother’s Day.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

There are still some limitations in the methodology. First, in the situational experiment, only one dress and one jacket were used as the advertising products, without covering other kinds of clothes or more diverse gifts. The characteristics of the advertised products may influence participants’ attitudes and interfere with the results. This may limit the reliability and generalizability of the conclusions. Second, only stereotypes about women’s individual autonomy were used to design the advertisements of femvertising, without considering other feminism issues such as diverse aesthetics. In addition, rhetorical phrases were used to design the femvertising copies, which may have interfered with how consumers perceived and responded to them. These materials may not fully represent the effectiveness of actual brands’ femvertising. Third, although advertising copies focused on product features and individual autonomy should be able to represent traditional advertising and femvertising theoretically, there is still a lack of an explicit manipulation checks. This may leave doubts about whether the experimental materials can truly reflect the independent variable and affect the validity of the conclusions. Fourth, only Chinese male consumers were surveyed, and most of the participants were younger than 40 and had a relatively high level of education, which may not represent male consumers of other age groups, socio-economic statuses, and nationalities. For example, consumers over 40 constitute a large portion of the gift market, and their perceptions of and responses to femvertising may be quite different from the younger generation.

This study has also inspired some further research directions. First, it has investigated the moderating effect of gift recipient, but there may also be some individual differences in male consumers’ response to female empowerment. Investigating moderating variables such as face orientation will help to identify the theoretical boundaries of femvertising. Second, there are tremendous differences in gender beliefs in different countries and ethnic groups. This study only investigated male consumers in China, so further studies on the perceptions and reactions of male consumers in other cultures will be beneficial to deepen our understanding of the effectiveness of femvertising. Third, it is also meaningful to investigate other contextual differences such as different occasions for gift giving, different kinds of products, and different price positions to enrich femvertising theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., Z.X. and D.Q.; methodology, Z.X.; software, S.Y.; validation, S.Y.; formal analysis, S.Y. and Z.X.; investigation, S.Y.; resources, Z.X. and D.Q.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.X.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, Z.X. and D.Q.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and D.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Project of Zhejiang Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences (2023N022), Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Hangzhou (Z23JC064), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72101233), and Fundamental Research Funds of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (24196121-Y).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since the situational experiment was anonymous and did not involve personal privacy or commercial interests, according to “Ethical Review Methods for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans” issued by the People’s Republic of China in February 2023, specifically Article 32 of Chapter 3, regarding exemption from ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adalı, G.; Yardibi, F.; Aydın, Ş.; Güdekli, A.; Aksoy, E.; Hoştut, S. Gender and advertising: A 50-Year bibliometric analysis. J. Advert. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Borquez, C.L.; Török, A.; Centeno-Velázquez, E.; Malota, E. Female stereotypes and female empowerment in advertising: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, W. The impact of advertising on women’s self-perception: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1430079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Koo, J.; Kim, D.Y. Femvertising of luxury brands: Message concreteness, authenticity, and involvement. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2023, 14, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Jamil, M.; AL-Hazmi, N.M.; Amir, A. Unveiling femvertising: Examining gratitude, consumers attitude towards femvertising and personality traits. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2297448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windels, K.; Champlin, S.; Shelton, S.; Sterbenk, Y.; Poteet, M. Selling feminism: How female empowerment campaigns employ postfeminist discourses. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Postfeminist heroes and heroines in contemporary Chinese advertising. Fem. Media Stud. 2023, 23, 4041–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Wang, Y. The myths of beauty, age, and marriage: Femvertising by masstige cosmetic brands in the Chinese market. Soc. Semiot. 2022, 32, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitbol, A.; Sternadori, M. Championing women’s empowerment as a catalyst for purchase intentions: Testing the mediating roles of OPRs and brand loyalty in the context of femvertising. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2019, 13, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A. Mapping Femvertising Research: A PRISMA driven systematic review of literature. Bull. Bus. Econ. 2024, 13, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiw, S.A.; Phillips, B.J.; Williams, D.E. Luxury brands’ use of CSR and femvertising: The case of jewelry advertising. Qual. Mark. Res. 2021, 24, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainneville, V.; Guèvremont, A.; Robinot, É. Femvertising or femwashing? Women’s perceptions of authenticity. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobande, F. Femvertising and fast fashion: Feminist advertising or fauxminist marketing messages? Int. J. Fash. Stud. 2019, 6, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterbenk, Y.; Champlin, S.; Windels, K.; Shelton, S. Is femvertising the new greenwashing? Examining corporate commitment to gender equality. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 177, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Poon, K.T.; Bai, Y. Sexism and the effectiveness of femvertising in China: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Sex Roles 2021, 84, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X. “The Big Women”: A textual analysis of Chinese viewers’ perception toward femvertising vlogs. Glob. Media China 2020, 5, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Munjal, A. Self-consciousness and emotions driving femvertising: A path analysis of women’s attitude towards femvertising, forwarding intention and purchase intention. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.M.; Casais, B. Consumer reactions towards femvertising: A netnographic study. Corp. Commun. 2021, 26, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; Roca, D.; Sadaf, L.; Obaid, A. How does femvertising work in a patriarchal context? An unwavering consumer perspective. Corp. Commun. 2024, 29, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, L.K.; Jacobson, C.; Liasse, D.; Lund, E. Femvertising and its effects on brand image: A study of men’s attitude towards brands pursuing brand activism in their advertising. In LBMG Strategic Brand Management: Masters Papers Series; Strategic Brand Management (SBM): Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kim, S. A comparison of Chinese consumers’ intentions to purchase luxury fashion brands for self-use and for gifts. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2013, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Teng, L.; Huang, X.; Foti, L.; Sun, C.; Yang, X. Face consciousness: The impact of gift packaging shape on consumer perception. Eur. J. Market. 2025, 59, 241–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, J.M.; Taris, T.W. Differentiating between gift giving and bribing in China: A guanxi perspective. Ethics Behav. 2022, 32, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kozinets, R.V.; Patterson, A.; Zhao, X. Gift giving in enduring dyadic relationships: The micropolitics of mother–daughter gift exchange. J. Consum. Res. 2024, 51, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, E. Investigating consumers’ reactions towards female-empowerment advertising (femvertising) and female-stereotypical representations advertising (sex-appeal). J. Islamic Mark. 2024, 15, 1078–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champlin, S.; Sterbenk, Y.; Windels, K.; Poteet, M. How brand-cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: A qualitative exploration of ‘femvertising’. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 1240–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M.; Muldrow, A.; Rosengren, S. Diversity and inclusion in advertising research. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; He, L. Consumer responses to femvertising: A data-mining case of Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty” on YouTube. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayer, L.T.; Coleman, C.A.; Gurrieri, L. Driving impact through inclusive advertising: An examination of award-winning gender-inclusive advertising. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkestam, N.; Rosengren, S.; Dahlen, M. Advertising “like a Girl”: Toward a Better Understanding of “Femvertising” and Its Effects. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.J.; Lee, M. A femvertising campaign always# Like A Girl: Video responses and audience interactions on YouTube. J. Gend. Stud. 2021, 32, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkepatt, G.; Bryant, A.; Hill, R.P.; Nunziato, J. Can advertising benefit women’s development? Preliminary insights from a multi-method investigation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, V.E. The impact of female empowerment in advertising (femvertising). J. Res. Mark. 2017, 7, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture Bue, A.C.; Harrison, K. Empowerment sold separately: Two experiments examine the effects of ostensibly empowering beauty advertisements on women’s empowerment and self-objectification. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.R.; Shanthi, R. The Role of Femvertising in Women’s Empowerment: A Focus on FMCG Brand Campaigns in India. ASR Chiang Mai Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2025, 12, e2025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordrostami, M.; Laczniak, R.N. Female power portrayals in advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 1181–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A.C.; Yannopoulou, N.; Gorton, M.; Lie, S. Guilty displeasures? How Gen-Z women perceive (in) authentic femvertising messages. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2024, 45, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, N.; Kumar, N. Feminism in advertising: Irony or revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Fem. Media Stud. 2022, 22, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Bryson, S.; Windels, K.; Karl, S. When brands don’t practice what they preach: A proposed model of the effects of brand hypocrisy and brand-cause fit on women’s responses to femvertisements. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guèvremont, A. Brand hypocrisy from a consumer perspective: Scale development and validation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Spry, A.; Ekinci, Y.; Vredenburg, J. From warmth to warrior: Impacts of non-profit brand activism on brand bravery, brand hypocrisy and brand equity. J. Brand Manag. 2024, 31, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, D. Will greenwashing result in brand avoidance? A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Grace, A.; Palmer, J.; Pham, C. Investigating the direct and indirect effects of corporate hypocrisy and perceived corporate reputation on consumers’ attitudes toward the company. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Phua, J. Effects of brand name versus empowerment advertising campaign hashtags in branded Instagram posts of luxury versus mass-market brands. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, N.T.; Hatzithomas, L.; Chaput, L. Femvertising practices on social media: A comparison of luxury and non-luxury brands. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 1285–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeloff, C.; Bruns, J. Effectiveness of femvertising communications on social media: How brand promises and motive attributions impact brand equity and endorsement outcomes. Corp. Commun. 2024, 29, 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bumb, A. Femluencing: Integration of femvertising and influencer marketing on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Mogilner, C. Experiential gifts foster stronger social relationships than material gifts. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 43, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Parvathy; Givi, J.; Dey, M.; Kent Baker, H.; Das, G. A bibliometric analysis on gift giving. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco-Illodo, I.; Heath, T. The ‘perfect gift’ and the ‘best gift ever’: An integrative framework for truly special gifts. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galak, J.; Givi, J.; Williams, E.F. Why certain gifts are great to give but not to get: A framework for understanding errors in gift giving. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, J.; Das, G. To earmark or not to earmark when gift-giving: Gift-givers’ and gift-recipients’ diverging preferences for earmarked cash gifts. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.K.; Broniarczyk, S.M. It’s not me, it’s you: How gift giving creates giver identity threat as a function of social closeness. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternadori, M.; Abitbol, A. Support for women’s rights and feminist self-identification as antecedents of attitude toward femvertising. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. What to say and what to do: The determinants of corporate hypocrisy and its negative consequences for the customer–brand relationship. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Jung, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Effects of CSR messages on apparel consumers’ Word-of-Mouth: Perceived corporate hypocrisy as a mediator. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2024, 42, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.M.; Hur, W.M. How does corporate hypocrisy reduce customer co-creation behaviors? Moderated mediation analysis of corporate reputation and self-brand connection. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2024, 42, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Korschun, D.; Troebs, C. Deconstructing corporate hypocrisy: A delineation of its behavioral, moral, and attributional facets. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; van Esch, P.; Northey, G.; Lee, M.S.W.; Dimitriu, R. Hypocrisy, skepticism, and reputation: The mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.; Yeo, J. Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Zakkariya, K.A.; Suki, N.M.; Islam, J.U. When going green goes wrong: The effects of greenwashing on brand avoidance and negative word-of-mouth. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freling, R.E.; Moore Koskie, M.; Freling, T.H.; Moulard, J.G.; Crosno, J.L. Exploring gift gaps: A meta-analysis of giver–recipient asymmetries. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, J.; Birg, L.; Lowrey, T.M.; Galak, J. An integrative review of gift-giving research in consumer behavior and marketing. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Mills, J.R. A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 232–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.C.; Yang, Y.K.; Cheng, Y.C. Does relationship matter?–Customers’ response to service failure. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2014, 24, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W.; Grimm, P.E. Communal and exchange relationship perceptions as separate constructs and their role in motivations to donate. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H. The role of relationship on time and monetary compensation. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Kim, K.K. Appropriate service robots in exchange and communal relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.G.; Bland, C.; Källberg-Shroff, M.; Tseng, C.-Y.; Montes-George, J.; Ryan, K.; Das, R.; Chakravarthy, S. Culture and the role of exchange vs. communal norms in friendship. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 53, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, C.; Kamvar, S.D.; Aaker, J. The shifting meaning of happiness. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 2, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Gallo, I. Consumers’ pursuit of material and experiential purchases: A review. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989, 18, 292–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Gurrea, R.; Flavián, C. Using augmented reality to reduce cognitive dissonance and increase purchase intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).