Abstract

The fintech sector is entering the maturity phase of the life cycle, in which customer brand engagement (CBE) is connecting companies and customers. The aim of this paper is to investigate the driving forces behind CBE in the fintech sector and its contribution to loyalty intentions. In the framework of service-dominant logic, a quantitative approach on 239 fintech users was undertaken to propose and validate a conceptual model of customer brand engagement in fintech, using Partial Least Square–Structural Equation Modeling. The results showed that the perception of personalization, the perception of interaction between customers and brands, and the perception of benefits contribute to CBE in fintech, and the latter is positively associated with loyalty intentions. This research contributes to the literature of brand engagement by offering an integrative framework to analyze CBE in the fintech sector.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the term fintech is used with a double meaning: on one hand, there are fintech companies that are imagining new tech-based financial services outside of the mainstream traditional financial sector; and, on the other hand, the term fintech designates financial services backed by technology that are offered to customers, both by innovative new companies and traditional companies from the classical financial sector. In this paper, fintech is designated as technology-based financial services offered by new or old companies, that have not been involved in the traditional financial sector prior to their fintech services offering.

The fintech sector is developing and in a continuous state of evolution. Alongside technological and operational factors, fintech success is based on consumer factors [1]. The fintech ecosystem includes a strong technological base, cutting-edge innovative financial services, innovative fintech companies, astute customers who learned to take advantage of fintech benefits, a developing marketing strategy to attract and retain customers, and a regulatory framework that is keeping up the pace with technological innovations [2,3].

Although they have a relatively short history behind them, fintech companies have managed to create a consistent customer base, with some of their customers being very involved and engaged with the company. What exactly makes these customers become engaged with fintech companies? Studies concerning customer engagement in fintech are few and dissipated. Sakas et al. [4] show that customer engagement for fintech can be boosted by video marketing strategies. Kini and Basri [2] indicate that customer engagement behaviors in fintech are supported by customer empowerment, and that both customer engagement behaviors and customer empowerment contribute to customer value. Using drive words and affective words on social media posts can lead to customers engagement with fintech companies [5]. Customer engagement mediates the relationship between the dimensions of customer value and customer-based brand equity in the case of a digital payment application [6]. Therefore, a research gap is identified to deepen the study of CBE in fintech. While previous studies addressed specific drivers of fintech engagement, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop and validate a model of CBE in fintech.

The aim of this research is to explore customer brand engagement in fintech, to identify what contributes to the formation of customer brand involvement in the fintech sector, and to assess its predecessors and determinants. The research is based on service-dominant logic (SDL). In the spirit of SDL, CBE is uniquely perceived and formed at an individual level, but still with a strong positive relationship with perceived value. This paper responds to the call of Hollebeek et al. [7] to speak on a “unified engagement voice” and to investigate CBE in various contexts, but in the SDL framework.

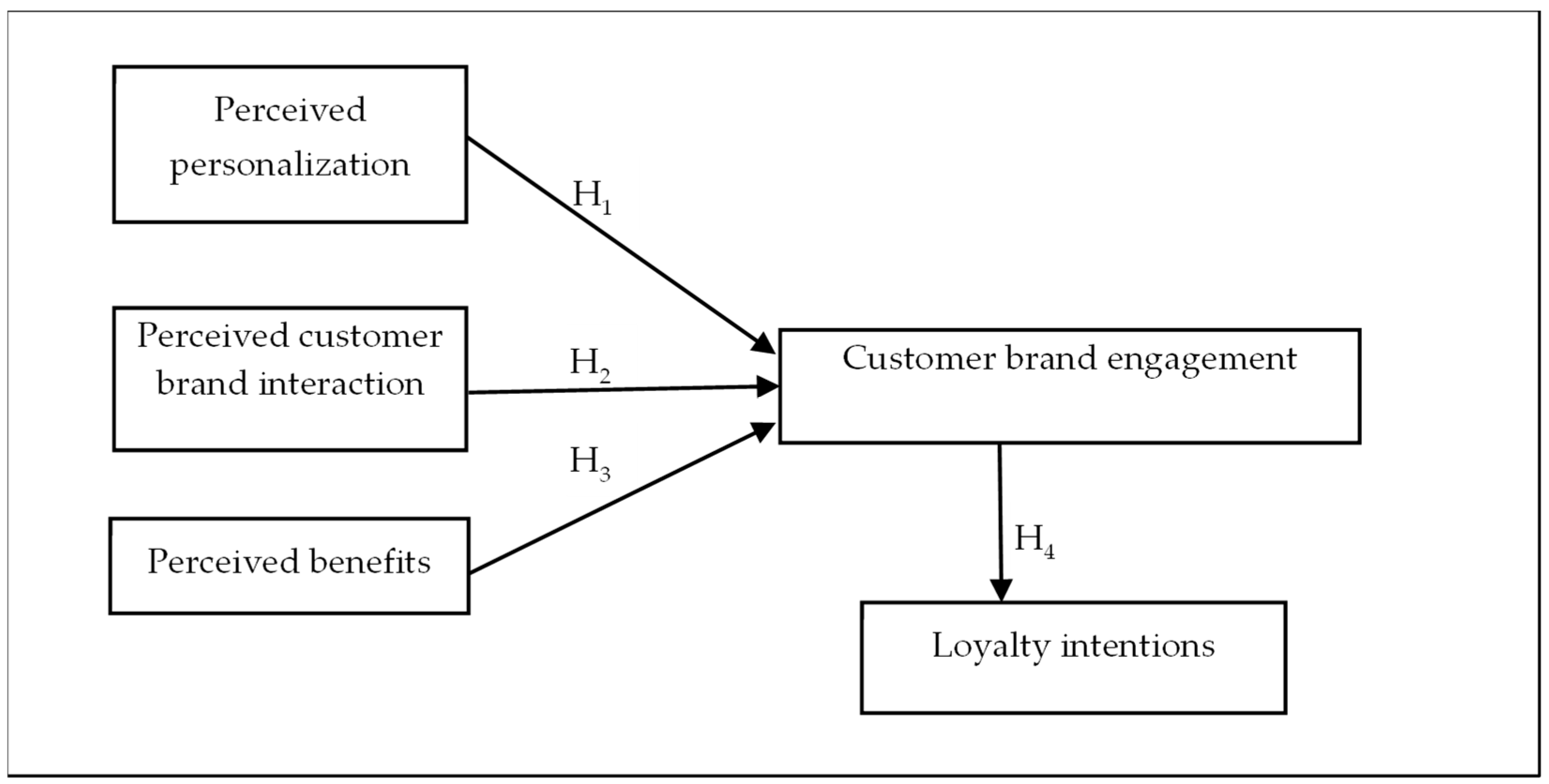

The research objectives are to identify if perceived customer brand interactions, perceived benefits, and perceived personalization contribute to CBE in fintech. Another research objective is to investigate if CBE is positively associated with loyalty intention. To achieve the research objectives, a conceptual model is proposed and later confirmed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).

This research paper makes a series of contributions. From a theoretical point of view, CBE in the fintech sector is analyzed with the SDL perspective. It can be concluded that perceived personalization, perceived customer brand interactions, and perceived benefits contribute to CBE in fintech, and the latter is a mechanism to create value for customers and companies. From a managerial perspective, several actionable recommendations are formulated that might stir CBE in fintech as a precursor for loyalty intentions.

This paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, the theoretical foundations of the research are laid down by analyzing the fintech CBE in SDL. In the Section 3, the conceptual model and intertwined hypotheses are proposed. The research methodology is depicted in Section 4 and the findings are presented in Section 5. In Section 6, results are discussed, later on followed by the theoretical contributions and practical implications of the research. This paper ends with its limitations, as well as suggesting further research avenues.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Service-Dominant Logic

SDL represents a meta-theoretical framework for a new perspective in marketing science. According to SDL, service is exchanged for service, creating value for all involved entities [8,9]. Goods and services are delivery support for the service, which embeds both operand but especially operant resources, consisting of skills and knowledge [8,9,10]. Customers do not buy products and services, they buy the service these products and services provide, and this service is the underlying reason for every purchase. Customers find unique value in obtaining this service; therefore, they are co-creating value [11]. Value is contextual and personal for each individual, as customers try to integrate the service into their life in combination with other resources at their disposal [8,10]. In SDL, all actors are resource integrators, trying to optimize their resources usage [12]. In this context, “mixing” technology with financial services led to the development of the fintech sector. Combining technology with innovation and business models redesign, the fintech sector disrupted the traditional financial sector by enabling superior value not just to customers, but to all involved actors. Fintech companies’ superior capacity to integrate technological resources allowed them to innovate and to deliver up-to-date financial services.

2.2. Customer Brand Engagement in Service-Dominant Logic

CBE is a relational construct, reflecting a strong customer connection with a brand [13]. CBE can be defined as “the level of an individual customer’s motivational, brand-related and context-dependent state of mind characterized by specific levels of cognitive, emotional and behavioral activity in brand interactions” [14]. CBE can be framed within the SDL, as customers develop long-term relationships with brands [15,16]. The company’s marketing investments are rewarded by CBE. In terms of SDL, customers co-create their service experiences, resulting in specific perceived benefits. Each experience is unique and individually perceived [15].

In the broader framework of customer engagement, CBE better captures customer and brand interactions. Customer engagement is defined as an individual psychological state resulting from the interaction with a focal brand [15]. The role of interactions is emphasized as customers play an essential role in the business–customer relationship, not only as receivers of value, but also as co-creators of value. Also, customer engagement is specific to each individual. Vivek et al. [17] highlight the role of interactions, as they define customer engagement comprising customers’ level of connection with the brand, often involving others.

CBE is considered as a multifaceted construct built from the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral perspective [18,19,20], ultimately being an indicator of customer–brand relationships [7,21]. Previous studies have shown that customer engagement with the brand is positively linked to customer co-creation and repurchase intention [19]. Other outcomes of CBE include behavioral intention, positive word-of-mouth, brand loyalty, and strong performance [22,23].

2.3. Fintech Brands and Customer Brand Engagement with Fintech Brands

Even if fintech companies appeared quite recently, they have managed to become strong brands. However, the literature on fintech brands is scarce. Bapat [24] shows that brand experience scores for fintech brands are higher than brand experience scores for traditional banks. However, other studies induce the idea that fintech brands are not as well sought-after as the traditional financial services brands [25]. Fintech companies offer services with better customer experience by changing the way customers approach financial services into a more relaxed and convenient one [26,27]. By keeping up with the latest available technology and constantly innovating, fintech companies can increase their brand equity [28]. Brand image is linked with customers’ intentions to use fintech services, therefore increasing the pressure on fintech companies to focus on creating strong brands [29].

3. Development of Hypothesis and Conceptual Model

CBE is considered to be the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral activity of consumers that associate a positive value to a brand during the interaction with it [18]. To measure CBE, various scales were proposed in the literature [21,30]. Most representative CBE scales include the following: the Hollebeek et al. [17] multidimensional scale (cognitive, affection, activation); the Dwivedi [13] multidimensional scale (vigor, dedication, absorption); the Solem and Pedersen [31] multidimensional scale (cognitive, emotional, physical); the Obilo et al. [20] multidimensional scale (content engagement, co-creation, advocacy, negative engagement); and the Ndhlovu and Maree [32] multidimensional scale (product context, reasoned behavior, affection, service context, social connection, identification, absorption).

For the purpose of this research, a three dimensional (cognitive, affective, activation) scale of CBE is adopted, following the approach of Hollebeek et al. [18]. In line with the previous literature, CBE is conceptualized as a second order reflective construct. The aim is to analyze the following possible determinants that can contribute to CBE in fintech: perceived personalization, perceived consumer brand interaction, and perceived benefits.

Perceived personalization is the personal belief of the customer that the fintech services meet the customer needs and that the fintech firm pays personal attention to the customer [33]. The personalization of fintech services enables each customer to assign a unique, individually perceived value to a service. Technology contributes decisively to perceived personalization as the available options increase with the new avenues that technology can offer. The ability of fintech companies to recognize customers and their recorded preferences contributes to the perceived personalization [34]. Personalization can contribute to the perceived increased status and importance of an individual [35,36]. Perceived personalization can contribute to the formation of positive feelings and emotional attachment to a brand [34] and thus contribute to brand engagement. Hence, it is postulated that the following are true:

H1: Perceived personalization is positively associated with CBE.

Perceived customer brand interaction is the interactivity with the fintech brand that the consumer is sensing [23]. In terms of SDL, the customer is always a co-creator of the service, together with the company and other actors. Fintech companies look for modalities to strengthen the interaction with the customers. A company that stimulates customer–brand interaction is perceived as more trustful, and customers feel secure to engage with that company [23]. Perceived customer–brand interaction might contribute to CBE by strengthening brand loyalty and stimulating positive word-of-mouth [37,38]. Brands can strengthen customer brand interaction by communicating with consumers in a variety of mediums and encouraging the consumers to share their experiences [19]: social media platforms, firm contact details, blogs, and influencers channels. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the following is true:

H2: Perceived customer brand interaction is positively associated with CBE.

The perceived benefits can be defined as the consumer’s belief that if they engage with a particular fintech company, they will be better off [39]. Perceived benefits are an intrinsic part of the value recognized by the customer [40]. In the fintech sector, perceived benefits might include service speed, services with reduced prices, round-the-clock service availability, and secure online transactions. In sum, these perceived benefits constitute a strong motivational factor to engage with the brand of the fintech company. Perceived benefits can compensate for the perceived risks in fintech adoption [41]. The customer who internalizes the perceived benefits becomes a customer engaged with the brand, talks about the brand, recommends the brand to others, and therefore has the credibility to attract new consumers. It can be therefore postulated that the following is true:

H3: Perceived benefits are positively associated with CBE.

Loyalty intentions reflect the will of customers to continue to buy financial services from the fintech provider [42]. Loyalty intentions are beneficial for the fintech company, as a solid customer base enables further development and growth of the company [13]. The results of loyalty are reinforced by the cognitive, emotional, and activating dimensions of CBE, ultimately leading to extended interactions between consumers and brands that could materialize in further acquisitions, recommendation, resistance to brand switching, and positive word-of-mouth [13,18]. Also, brand attachment is associated with positive word-of-mouth [43], as engaged consumers became brand evangelists. CBE and loyalty intentions are a self-reinforcing mechanism: repeated acquisitions lead to interactive brand experiences in the post-consumption stage [44]. Engaged consumers tend to maintain strong beliefs, enrich their emotions, and repeat purchases with fintech brands [23,45,46].

H4: CBE is positively associated with loyalty intentions.

The graphical representation of the research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research model.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

To analyze the antecedents of customer brand engagement in the fintech sector, research among Romanian consumers who use the fintech service Revolut is implemented. Today, Revolut represents a powerful and well-established symbol of fintech sector success, being categorized as a digital bank or neobank. Revolut offers a wide range of financial services for retail customers and businesses such as multi-currency accounts, international transfers, payments, currency exchange, budgeting tools, portfolio investments, etc. The company has more than 35 million retail customers around the world, out of which 3 million reside in Romania [47].

Participants in the research are present and former students at a large Romanian university. Initially, an email invitation was sent to over 1800 individuals to participate in an online survey about their attitudes and behaviors towards fintech usage. To qualify for the study, participants had to have used Revolut in the last six months. The period of the study was February–March 2024. Only 251 completed questionnaires were received, but after eliminating those with incomplete responses, a total number of 239 valid responses could be further analyzed.

The sample structure (Table 1) shows that males are the predominant users of fintech services, and these services have a higher prevalence in the younger age groups. The sample is relatively equally distributed among levels of completed educational stages. It can be appreciated that the sampling structure reflects the fintech diffusion among consumers strata.

Table 1.

Sample structure.

4.2. Measures

For testing the model, structural equation modeling using partial least squares with SmartPLS 4 software was employed. Constructs were first operationalized according to the existing literature; scales were adapted to fit the research scope (Table 2). The adaptation process required intensive consultation among the authors, followed by rigorous variable confirmation measurements, and also a pilot study. The variables were first generated in English, then they were translated into Romanian, and back to English by a different person to ensure compliance with retroversion principles [48]. A five-point Likert scale was used to measure the selected variables. Following the exploratory factor analysis, it was found that the item loadings were above 0.7, therefore convergent validity is not an issue (Table 2).

Table 2.

Loading values.

The results of the measurement model (see Table 3), show that both Cronbach’s α and the composite reliability (CR) met the minimum threshold of 0.7 for each construct, thus establishing the reliability of the constructs [49]. By further relying on the confirmatory factor analysis, an average variance extracted (AVE) higher than the recommended threshold of 0.5 could be measured for each construct [50].

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

For the reflectively measured constructs, such as the ones in the conceptual model, a discriminant validity check was also performed (Table 4). The HTMT results indicate that there are no discriminant validity issues [51].

Table 4.

HTMT results.

5. Findings

The regression coefficients of the computed model are depicted in Table 5, along with the significance level obtained when testing the model with the help of a bootstrap algorithm on 1000 subsamples. The coefficient of determination of the variable CBE is R2 = 0.600. For the variable loyalty intentions, the coefficient of determination is R2 = 0.494. The results show that this model is well conceptualized, and its prediction power is high.

Table 5.

The structural model.

All the hypotheses are validated. Perceived personalization is positively associated with consumer brand engagement (H1: β = 0.223, t = 3.464, p < 0.001). A committed customer appreciates tailored financial services.

Perceived customer brand interaction is positively associated with CBE (H2: β = 0.240, t = 3.841, p = 0.001). A company that listens to its customers and involves the customers in the creation of new financial services is more likely to generate stronger customer brand engagement.

The results show that perceived benefits are positively associated with CBE (H3: β = 0.375, t = 4.778, p < 0.001). It is important that the perceived attractiveness of benefits is to be experienced in the long term.

CBE is positively associated with loyalty intentions (H4: β = 0.652, t = 14.029, p < 0.001). From the fintech perspective, behavioral and emotional loyalty of the customers is the ultimate goal of the brand–customer relationship.

6. Discussions and Implications

This study proved that CBE can be relevant for fintech’s maturity life-cycle phase. CBE connects companies and customers, creating value for both parties. Perceived personalization is a key driver of CBE in fintech. The success of fintech companies relies heavily on personalization [52]. In terms of the SDL theory, the actors in the fintech sector, firms and clients alike, are involved in creating value. Marketing with customers, not marketing to customers [53], is an imperative that finds its expression in personalization.

Fintech companies co-create their financial products and services together with their clients [9]. Customers are involved in the process of conception, design, testing, and implementation of these financial services. Customers who participate in the co-creation process experience a sense of belonging, which can strengthen the relationship with the company, and thus positively influence CBE. Co-developing and socializing are customer engagement sub processes [54] and essential components of the customer brand interaction. Customer socializing is a source of new ideas for fintech companies [30]. Interactions between actors are essential for the parties involved to be able to co-create and generate value.

For online financial services provided by fintech, perceived benefits tend to be a stronger driver of CBE than perceived personalization or perceived customer brand interaction. In the specific case of the fintech sector, consumers prioritize perceived benefits. Once seized by consumers, perceived benefits represent an immediate stimulus to access fintech services and are a driver of CBE. Perceived benefits are an important element of strategic benefit [9]. In addition, perceived benefits are also a determinant of loyalty. The more benefits customers experience, the more they will be attracted to the company. Fintech comes with obvious benefits over classic financial services: lower transaction costs, increased speed, round-the-clock availability, and tailored services to individual needs [55]. The customer is willing to engage with fintech brands that offer perceived benefits. CBE acts as a mantra for all of the benefits fintech has to offer, encompassing all the positive associations of a fintech brand. CBE has a positive impact on loyalty intentions [23,45,46,54].

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

By framing CBE in the SDL theory, this research contributes to the understanding of CBE theoretical relationships with selected concepts, and this can help the concept’s further investigation in other areas [7]. This paper makes a number of contributions to the theory of SDL.

Firstly, fintech companies use and integrate their operant resources (knowledge, competences, capabilities, and technologies) to create value for customers. Their know-how on the tech side of “fintech” is what has the potential to disrupt the market. This view accommodates the SDL, in that the customer is an operant resource that must be actively integrated by the company in the efforts to generate valuable fintech services [8]. The customer is not acted upon to feel the marketing influence from the fintech company, the customer is seen as a partner and as a resource integrator. In this view, the customer is not exogenous to the fintech company, but an asset to the fintech organization. Fintech companies, customers, the involved technologies, and other interactions constitute the dynamic fintech eco-system [9].

Secondly, encouraging interactions is seen as a way to co-create value [56]. Through direct or indirect interactions with the fintech brand is how a customer co-creates value. Customer brand interactions in the fintech sector are part of the relational perspective that surrounds the fintech ecosystem. Fintech–customer interactions are not limited to this dyadic view; instead, the customer can capture the value of fintech service by comparing it against other financial services offers.

Thirdly, from the SDL perspective, perceived benefits should be seen as a source of CBE. Value is co-created by different actors, including beneficiaries [9], and recognition of this value is capitalized by the customer in everyday use of fintech service. Perceived benefits help to capture and discover value-in-use. The customers engaged with the fintech brands actively search for further perceived benefits to reinforce their engagement, therefore co-creating value from the recognized perceived benefits. Fintech companies that involve customers in the design of benefits enhance CBE and build brand equity [57]. Focusing on the perceived benefits of the beneficiary, the fintech company should always innovate and not stick to the traditional wisdom of protecting the market share [12].

Fourthly, the empirical model was successfully tested, which opens new theoretical avenues for understanding CBE antecedents. CBE in fintech is enhanced by a digital environment which can offer personalization, customer brand interactions, and value in context, all under the form of perceived benefits.

6.2. Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, several actionable measures to take full advantage of the practical implications of the validated model are proposed. Having customer loyalty as a main goal, fintech managers must not overlook the importance of CBE. CBE is a proxy for a long-term, fruitful relationship with the customer [17]. To build a successful and meaningful relationship with customers is to generate CBE. Constant monitorization of CBE in fintech might offer a dynamic assessment of its evolution and its contribution to loyalty intentions [58]. CBE should be perceived both as a key performance indicator itself and as a determinant of other important outcomes, such as brand loyalty [22]. As competition in the fintech sector is expanding, brand management strategies should place CBE at the center of their focus.

Personalized services in fintech contribute to CBE. To offer personalized financial services, technology is of great help [59]. Customer preferences can be recorded, learned, and displayed at each interaction [23]. Artificial intelligence and data science can be used to figure out and predict customer intentions, emotions, preferences, and their forecasted requests to access the fintech [60]. Ubiquitous finance implies that customers make use of personalized financial services across devices and platforms [61].

Enhanced interactions represent an envisaged direction for fintech companies to reach CBE and to be successful. In this respect, fintech companies must encourage customer–brand interactions so that actual and potential customers can successfully co-create value. Their offers should be always adapted to customer needs and be based on a “sense-and-respond” strategy [8,62]. Relentless interaction with customers can lead to the identification of better solutions to meet their needs. All available channels should be open for bi-directional communication. Prompt communication reduces customer anxiety, especially in the case of a fintech, where a customer’s money is a sensitive issue [63]. The analysis of social media communication and netnography can also offer precious insights on how customers use fintech to co-create value [64].

Enhanced benefits for customers are what differentiate engaged customers from ordinary customers. Perceived benefits are weighted against perceived risks [65,66]. Reducing perceived risks might shed light on the benefits. Usually, for older customers or less tech-savvy customers, the innovative character of fintech service might contribute to their reluctance to use it. An effort from fintech companies to educate customers about the benefits of fintech should be put in place, and this can further enhance CBE [66].

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are a number of limitations of this research that do not diminish its contribution but require a circumspect approach. The population out of which the sample was extracted is just from one country, therefore sampling in a single country needs to be enhanced with multiple-country sampling and various cultural approaches to fintech usage. CBE in fintech was studied in relation to a single company, which indeed offers a wide range of fintech services. Other possible fintech companies and services could be included in future studies. Considering the fact that our respondents all have a high-school diploma, another possible limitation might deal with sample non-inclusion of people with lower degrees who also use fintech services. Model development and variable definitions could be enhanced. For example, perceived personalization variable might include other relevant items, to capture personalization in fintech apps, such as perceived personal interactions, perceived app design options, and perceived service plan choice. Perceived customer brand interaction variable is constructed around items drawing on social media interactions, potentially skipping important interactions within the app or service itself. However, this does not affect content validity, as many interactions these days evolve around social-media channels. With regard to the antecedents of CBE in fintech, the model can be supplemented with other factors that might impact CBE, and potentially account for unexplained variability such as trust, perceived risks, and perceived innovation. Finally, the cross-sectional approach can be enhanced with longitudinal studies to investigate the evolution of CBE over time.

The research opens up an avenue for a potentially interesting and diversified research agenda. Firstly, one possible future direction could envisage the generalizations of the antecedents of CBE across other sectors. Can the conceptual model be replicated successfully in other contexts? Are there any other particular relevant antecedents in cases of other sectors? Secondly, further studies might investigate the investments that customers are making in brand engagement and how this affects their relationship with the brand. Thirdly, studies on negative engagement or customers who do not want to engage or have a low propensity to engage with a brand [7] need particular attention. What are the consequences of low or negative engagement? Fourthly, further studies could try to assess the contribution of CBE to performance and the managerial, actionable directions to stimulate CBE. Last but not least, a potential area of interest might investigate how CBE specifically contributes to value creation for all involved actors, companies, and beneficiaries alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; methodology, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; software, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; validation, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; formal analysis, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; investigation, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; data curation, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; writing—review and editing, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; visualization, C.M.B., S.-R.G., D.V.P. and D.-C.D.; supervision, C.M.B.; project administration, C.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within and with the support of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Economic and Social Sciences, INCESA (Research Hub for Applied Sciences), University of Craiova.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBE | Customer brand engagement |

| SDL | Service-dominant logic |

References

- Werth, O.; Cardona, D.R.; Torno, A.; Breitner, M.H.; Muntermann, J. What determines FinTech success?—Taxonomy-based analysis of FinTech success factors. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, A.N.; Basri, S. Customer Empowerment and Engagement Behaviours Influencing Value for FinTech Customers: An Empirical Study from India. Organ. Mark. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 14, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Huang, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, M. Uncovering research trends and opportunities on FinTech: A scientometric analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 24, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D.P.; Giannakopoulos, N.T.; Terzi, M.C.; Kamperos, I.D.G.; Kanellos, N. What is the connection between Fintechs’ video marketing and their vulnerable customers’ brand engagement during crises? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2024, 42, 1313–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShabbirHusain, R.V.; Pathak, A.A.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Annamalai, B. The power of words: Driving online consumer engagement in Fintech. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 42, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, D.; Hollebeek, L.D. Customer value, customer engagement, and customer-based brand equity in the context of a digital payment app. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Srivastava, R.K.; Chen, T. SD logic–informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nariswari, A.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominat logic. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Services; Gallouj, F., Gallouj, C., Monnoyer, M.C., Rubalcaba, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. An Overview of Service-Dominant Logic. In The SAGE Handbook of Service-Dominant Logic; Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela-Huotari, K.; Vargo, S.L. Why service-dominant logic. In The SAGE Handbook of Service-Dominant Logic; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, A. A higher-order model of consumer brand engagement and its impact on loyalty intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Dalela, V.; Morgan, R.M. A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; De Oliveira, M.J. Driving consumer–brand engagement and co-creation by brand interactivity. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obilo, O.O.; Chefor, E.; Saleh, A. Revisiting the consumer brand engagement concept. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Sarstedt, M.; Menidjel, C.; Sprott, D.E.; Urbonavicius, S. Hallmarks and potential pitfalls of customer-and consumer engagement scales: A systematic review. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Santini, F.; Ladeira, W.J.; Pinto, D.C.; Herter, M.M.; Sampaio, C.H.; Babin, B.J. Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; Leung, W.K.; Sharipudin, M.N.S. The role of consumer-consumer interaction and consumer-brand interaction in driving consumer-brand engagement and behavioral intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, D. Exploring advertising as an antecedent to brand experience dimensions: An experimental study. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2018, 23, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Mercado, P.; Karthik, M.; Mishra, R.K. What’s in a brand name? Preferences of mobile wallets in India under a shifting regulation. Int. J. Bus. Forecast. Mark. Intell. 2020, 6, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siek, M.; Sutanto, A. Impact analysis of fintech on banking industry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Jakarta/Bali, Indonesia, 19–20 August 2019; Volume 1, pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, A.; Desai, R. Reviews and directions of FinTech research: Bibliometric–content analysis approach. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2024, 29, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chang, Y. Technology leadership, brand equity, and customer loyalty towards fintech service providers in China. In Proceedings of the AMCIS Twenty-Fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–18 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Linh, N.H.N.; Tuyen, D.Q. Factors affecting the intention to use Fintech services in Vietnam. Econ. Manag. Bus. 2020, 275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Schee, B.A.; Peltier, J.; Dahl, A.J. Antecedent consumer factors, consequential branding outcomes and measures of online consumer engagement: Current research and future directions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2020, 14, 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solem, B.A.A.; Pedersen, P.E. The role of customer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualisation, measurement, antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2016, 10, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, T.; Maree, T. Consumer brand engagement: Refined measurement scales for product and service contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaid, S.I.; Wigand, R.T. Measuring the quality of e-service: Scale development and initial validation. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2009, 10, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Shin, D.H.; Gong, T. The role of personalization, engagement, and trust in online communities. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Zhao, L. What motivates customers to participate in social commerce? The impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Q.; Pham, T.N.; Nguyen, L.H.L. How to drive brand engagement and EWOM intention in social commerce: A competitive strategy for the emerging market. J. Compet. 2020, 12, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Wyllie, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Voola, R. Enhancing brand relationship performance through consumer participation and value creation in social media brand communities. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S. Applying uses and gratifications theory to understand customer participation in social media brand communities: Perspective of media technology. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Raman, T.V. The interplay of perceived risk, perceive benefit and generation cohort in digital finance adoption. EuroMed J. Bus. 2023, 18, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Malhotra, A. E-S-Qual: A Multiple-Item Scale for Assessing Electronic Service Quality. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaobelina, L.; Prom Tep, S.; Arcand, M.; Ricard, L. The relationship of brand attachment and mobile banking service quality with positive word-of-mouth. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzer, D.J.; Van Tonder, E. Loyalty intentions and selected relationship quality constructs: The mediating effect of customer engagement. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, C.; Nyadzayo, M.W.; Johnson, L.W. Antecedents of consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 558–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Fatma, M.; Islam, J.U.; Rather, R.A.; Shahid, S.; Sigurdsson, V. Mobile app vs. desktop browser platforms: The relationships among customer engagement, experience, relationship quality and loyalty intention. J. Mark. Manag. 2023, 39, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revolut. Revolut Tops 10 Million Retail Customers in the CEE Region and Strengthens Its Position as a Regional Digital Bank. 2023. Available online: https://www.revolut.com/en-RO/news/revolut_tops_10_million_retail_customers_in_the_cee_region_and_strengthens_its_position_as_a_regional_digital_bank/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Brislin, R.W. Back Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Errors: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozman, D.; Liebenau, J.; Mangan, J. The innovation mechanisms of fintech start-ups: Insights from SWIFT’s innotribe competition. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F. Marketing’s evolving identity: Defining our future. J. Public Policy Mark. 2007, 26, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Zhang, J. FinTech, Lending and Payment Innovation: A Review. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 49, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M., Jr.; Arnould, E.J. How brand community practices create value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Measuring customer engagement in social media marketing: A higher-order model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2633–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ye, Q.; Xia, H. Optimal interest rates personalization in FinTech lending. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 26, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Yang, Q.; Yu, P.S. Data science and AI in FinTech: An overview. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 12, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, R.; Fridgen, G.; Chang, Y. The future of fintech—Towards ubiquitous financial services. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeckel, S.H. Adaptive Enterprise: Creating and Leading Sense-and-Respond Organizations; Harvard School of Business: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.H.; Kim, D.J.; Hur, Y.; Park, K. An Empirical Study of the Impacts of Perceived Security and Knowledge on Continuous Intention to Use Mobile Fintech Payment Services. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P.; Quinton, S. More-than-human netnography. J. Mark. Manag. 2018, 34, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S. What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech?: The moderating effect of user type. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Raza, S.A.; Khamis, B.; Puah, C.H.; Amin, H. How perceived risk, benefit and trust determine user Fintech adoption: A new dimension for Islamic finance. Foresight 2021, 23, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).