Unravelling the Effects of Privacy Policies on Information Disclosure: Insights from E-Commerce Consumer Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Privacy Calculus Theory

2.2. Privacy Policy

2.3. Privacy Control

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.2. Experimental Design

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Data Characteristics

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

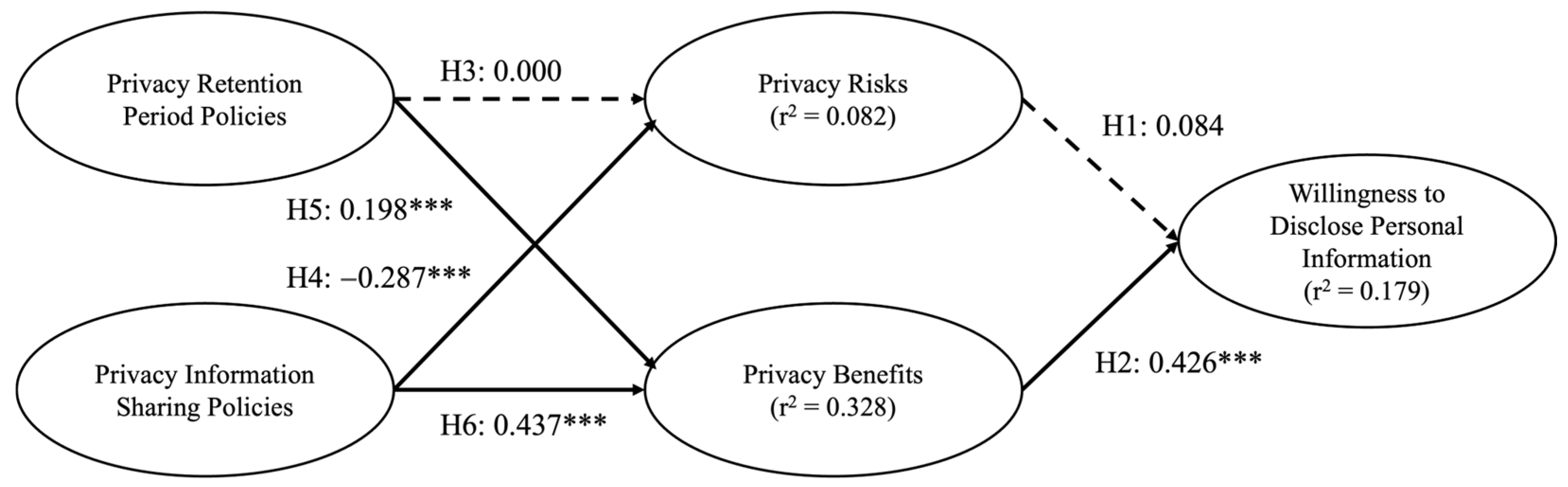

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, H.; Park, S.; Hyun, D. A priority analysis of policy implementation tasks for the revitalization of the big data industry: Based on the analysis of policy priority using AHP. Korean J. Broadcast. Telecommun. Stud. 2021, 35, 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomakers, E.-M.; Lidynia, C.; Ziefle, M. The Role of Privacy in the Acceptance of Smart Technologies: Applying the Privacy Calculus to Technology Acceptance. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, K.A.; Egelman, S.; Han, C.; On, A.E.B.; Reyes, I. Can You Pay For Privacy? Consumer Expectations and the Behavior of Free and Paid Apps. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 2020, 35, 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Wu, Y.; Yu, J.; Land, L. Love at First Sight: The Interplay Between Privacy Dispositions and Privacy Calculus in Online Social Connectivity Management. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2018, 19, 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschprung, R.; Toch, E.; Bolton, F.; Maimon, O. A methodology for estimating the value of privacy in information disclosure systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.Y.; Egelman, S.; Cranor, L.; Acquisti, A. The Effect of Online Privacy Information on Purchasing Behavior: An Experimental Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Natour, S.; Cavusoglu, H.; Benbasat, I.; Aleem, U. An empirical investigation of the antecedents and consequences of privacy uncertainty in the context of mobile apps. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 1037–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, K.; Park, Y.; Ahn, J. Willingness to provide personal information: Perspective of privacy calculus in IoT services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, J.; Jun, S. The Role of Consumers’ Privacy Awareness in the Privacy Calculus for IoT Services. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 3173–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oh, D. The Effect of Privacy Policy Awareness on the Willingness to Provide Personal Informationin Electronic Commerce. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2016, 18, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Koo, C.; Lee, D. An Empirical Study of Trust Building though Privacy Policies in Sharing Economy: Accumulated Effects of Cultural Background. J. Korea Serv. Manag. Soc. 2017, 18, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Hwang, G. The effect of Privacy Factors on the Provision Intention of Individual Information from the SNS Users. J. Digit. Converg. 2016, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, J. An Empirical Research on Information Privacy Concern in the IoT Era. J. Digit. Converg. 2016, 14, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Huang, S.Y.; Yen, D.C.; Popova, I. The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jai, T.C.; King, N.J. Privacy versus reward: Do loyalty programs increase consumers’ willingness to share personal information with third-party advertisers and data brokers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. A Study on the Institutional Plan on Financial Consumer Protection in the Case of Unfair Settlement due to Information Leak: Focusing on the Contents of the Comprehensive Digital Finance Innovation Plan. Korean J. Ind. Secur. 2020, 10, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Teo, H.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Agarwal, R. The Role of Push-Pull Technology in Privacy Calculus: The Case of Location-Based Services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, R.S.; Wolfe, M. Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Developmental Theory. J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M.J.; Armstrong, P.K. Information Privacy Concerns, Procedural Fairness, and Impersonal Trust: An Empirical Investigation. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M.J.; Bies, R.J. Consumer Privacy: Balancing Economic and Justice Considerations. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, I.M.; Eid, M.I.; Abed, A. The willingness to disclose personal information: Trade-off between privacy concerns and benefits. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2019, 28, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J. A Study on the Internet User’s Economic Behavior of Provision of Personal Information: Focused on the Privacy Calculus, CPM Theory. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.X.; Deng, H. Exploring privacy paradox in contact tracing apps adoption. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 1725–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J. Impact of Privacy Concern and Institutional Trust on Privacy Decision Making: A Comparison of E-Commerce and Location-Based Service. J. Korea Ind. Inf. Syst. Res. 2017, 22, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltgen, C.L.; Smith, H.J. Falsifying and withholding: Exploring individuals’ contextual privacy-related decision-making. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Priego, N.; van Bavel, R.; Monteleone, S. The disconnection between privacy notices and information disclosure: An online experiment. Econ. Politica J. Anal. Institutional Econ. 2016, 33, 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. The role of privacy policy on consumers’ perceived privacy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, P. The impacts of the privacy policy on individual trust in health information exchanges (HIEs). Internet Res. 2020, 30, 811–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J. Impacts of Female College Students’ Perceived Security on Attitude Toward SNS after Reading Privacy Policies of SNS. J. Consum. Cult. 2018, 21, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, K.; Teng, C. Understanding the influence of privacy protection functions on continuance usage of push notification service. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 74, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, Q. Privacy Concerns, Perceived Intrusiveness, and Privacy Controls: An Analysis of Virtual Try-On Apps. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Luo, X.; Carroll, J.M.; Rosson, M.B. The personalization privacy paradox: An exploratory study of decision making process for location-aware marketing. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimodugno, M.; Hallman, S.; Plaisent, M.; Bernard, P. The effect of privacy concerns, risk, control, and trust on individuals’ decisions to share personal information: A game theory-based approach. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2090, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutimukwe, C.; Kolkowska, E.; Grönlund, Å. Information privacy in e-service: Effect of organizational privacy assurances on individual privacy concerns, perceptions, trust and self-disclosure behavior. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H. An Empirical Study on the Privacy Protection Intention and Behavior of B2C Delivery Services User: TRA (Theory of Reasoned Action) Approach. Korea Logist. Rev. 2020, 30, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Lee, A.R.; Kim, K.K. Investigating the Privacy Paradox in Facebook Based on Dual Factor Theory. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2016, 17, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anic, I.; Škare, V.; Kursan Milaković, I. The determinants and effects of online privacy concerns in the context of e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 36, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, N.F.; Krishnan, M.S. The Personalization Privacy Paradox: An Empirical Evaluation of Information Transparency and the Willingness to Be Profiled Online for Personalization. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Koo, C. Exploring Factors Affecting Attitude toward Disclosure of Personal Information in Restaurants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Tour. Sci. 2021, 45, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Albano, V.; Xu, H.; D’Atri, A.; Hart, P. Individuals’ Attitudes Towards Electronic Health Records: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. In Advances in Healthcare Informatics and Analytics; Gupta, A., Patel, V., Greenes, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 19, pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sarathy, R.; Xu, H. The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. A Moderating Effect of Use of Interaction Privacy Controls on the Relationship between Privacy Concerns and Self-disclosure. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Inf. 2020, 25, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, H. Is There a Privacy Paradox in the Online Purchasing Context?: The Study on the Effects of Privacy Concern and Online Purchasing Behavior. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.B.; De Figueiredo, J.C.B. Effects of perceived risks and benefits in the formation of the consumption privacy paradox: A study of the use of wearables in people practicing physical activities. Electron. Mark. 2022, 32, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I. Difference of Privacy Paradox on Open and Closed SNS. Informatiz. Policy 2020, 27, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, J.; Widjaja, T.; Buxmann, P. Handle with care: How online social network providers’ privacy policies impact users’ information sharing behavior. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Rha, J. Effects of Informed Consent on Young Consumers’ Willingness to Provide Personal Information and Intention to Use Location-based Mobile Commerce. Consum. Policy Educ. Rev. 2016, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Operational Definitions | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Benefits | The degree of benefit the subject perceives to be derived from providing personal information to the controller | PIT1: Using this internet service is useful to me. |

| PIT2: Using this internet service is worth it to me. | ||

| PIT3: Using this internet service is helpful to me. | ||

| PIT4: Using this internet service is beneficial to me. | ||

| Privacy Risks | Perceived risk of the subject’s behavior regarding the controller’s use of personal information | PRI1: I understand that providing my personal information to this internet service involves risks. |

| PRI2: I believe that providing my personal information to this internet service may cause unforeseen problems. | ||

| PRI3: I think there is a lot of uncertainty (insecurity) in providing personal information to this internet service. | ||

| PRI4: I believe that providing personal information to this internet service may result in a loss to me. | ||

| PRI5: I do not believe it is safe to provide personal information to this internet service. | ||

| Willingness to Disclose Personal Information | The extent to which the subject is willing to provide personal information to the controller | IPA1: I willingly provide my personal information when requested for the use of this internet service. |

| IPA2: I generally provide personal information when asked for it in order to use this internet service. | ||

| IPA3: I readily provide my personal information when it is requested for using this internet service. | ||

| IPA4: I frequently provide personal information when asked for it in order to use this internet service. |

| Variables | Operational Definitions | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Retention Period Policies | Awareness of how long information controllers keep subjects’ personal information | PRPP1: I trust that the internet service will take steps to ensure that my personal information is no longer used when I want it to be. |

| PRPP2: When I want, I will be able to have my personal information deleted from this internet service. | ||

| PRPP3: I believe that this internet service will stop using the data it analyzes about me when I want it to. | ||

| PRPP4: When I want, I will be able to have this internet service delete the data it analyzed about me. | ||

| Privacy Information Sharing Policies | Awareness that information controllers may provide subjects’ personal information to external parties | PPCP1: I believe that my personal information will only be utilized by this internet service that I am a member of. |

| PPCP2: I believe that my membership information is only analyzed by this internet service that I am a member of. | ||

| PPCP3: I think other companies, not the one I signed up with, will not be able to use the information I provided for this internet service. | ||

| PPCP4: I believe that other companies, not the one I signed up with, will not be able to analyze and utilize the information I provided for this internet service. |

| Situations | Personal Information Retention | Personal Information Sharing |

|---|---|---|

| Situation 1 | Deletion upon withdrawal of membership | No provision of personal information to a third party company |

| Situation 2 | Retention for customer convenience even after withdrawal | No provision of personal information to a third party company |

| Situation 3 | Deletion upon withdrawal of membership | Provided to a third party company for product preference research |

| Situation 4 | Retention for customer convenience even after withdrawal | Provided to a third party company for product preference research |

| Demographics | Response | Count | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 94 | 50.8 |

| female | 91 | 49.2 | |

| Age | ~19 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 20~29 | 38 | 20.5 | |

| 30~39 | 57 | 30.8 | |

| 40~49 | 56 | 30.3 | |

| 50~59 | 26 | 14.1 | |

| 60~ | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Education Level | High school diploma or less | 23 | 12.4 |

| Community college dropout/graduate | 23 | 12.4 | |

| Bachelor’s degree program dropout/graduate | 122 | 65.9 | |

| Graduate school dropout/graduate | 17 | 9.2 | |

| Internet Usage Level | It is essential to have someone else’s help when using the internet. | 7 | 3.8 |

| I need some assistance from others when using the internet. | 8 | 4.3 | |

| I can use the internet independently. | 19 | 10.3 | |

| I have no trouble using the internet. | 73 | 39.5 | |

| I can help others use the internet. | 78 | 42.2 |

| Situations | Respondents | Analysis Sample (After Outlier Removal) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation 1 | 50 | 25.4% | 46 | 24.9% |

| Situation 2 | 54 | 27.4% | 51 | 27.6% |

| Situation 3 | 55 | 27.9% | 52 | 28.1% |

| Situation 4 | 38 | 19.3% | 36 | 19.5% |

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| privacy retention period policies | PRPP1 | 3.01 | 1.234 | −0.091 | −1.145 |

| PRPP2 | 3.17 | 1.179 | −0.109 | −1.064 | |

| PRPP3 | 2.97 | 1.242 | 0.079 | −1.157 | |

| PRPP4 | 3.14 | 1.224 | −0.046 | −1.145 | |

| privacy information sharing policies | PPCP1 | 3.22 | 1.205 | −0.236 | −1.002 |

| PPCP2 | 3.19 | 1.270 | −0.259 | −1.111 | |

| PPCP3 | 3.04 | 1.257 | 0.028 | −1.163 | |

| PPCP4 | 3.01 | 1.223 | 0.098 | −1.093 | |

| privacy benefits | PIT1 | 3.26 | 0.927 | −0.304 | 0.104 |

| PIT2 | 3.17 | 0.951 | −0.277 | −0.059 | |

| PIT3 | 3.44 | 0.931 | −0.424 | 0.107 | |

| PIT4 | 3.18 | 0.918 | −0.235 | −0.025 | |

| privacy risks | PRI1 | 3.49 | 0.927 | −0.622 | 0.038 |

| PRI2 | 3.55 | 0.920 | −0.834 | 0.662 | |

| PRI3 | 3.49 | 0.841 | −0.528 | 0.219 | |

| PRI4 | 3.33 | 0.929 | −0.581 | 0.061 | |

| PRI5 | 3.41 | 0.862 | −0.322 | 0.170 | |

| willingness to disclose personal information | IPA1 | 3.05 | 0.864 | −0.207 | 0.299 |

| IPA2 | 3.35 | 0.814 | −0.715 | 0.418 | |

| IPA3 | 2.94 | 0.910 | −0.101 | −0.179 | |

| IPA4 | 3.06 | 0.904 | −0.341 | −0.201 | |

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|

| privacy retention period policies | 0.929 | 4 |

| privacy information sharing policies | 0.938 | 4 |

| privacy benefits | 0.925 | 4 |

| privacy risks | 0.898 | 5 |

| willingness to disclose personal information | 0.854 | 4 |

| Situations | Privacy Retention Period Policies (Mean) | Privacy Information Sharing Policies (Mean) |

|---|---|---|

| Situation 1 | 3.35 | 3.53 |

| Situation 2 | 2.76 | 3.20 |

| Situation 3 | 3.41 | 2.94 |

| Situation 4 | 2.65 | 2.70 |

| Situation | Count | Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRPP | 1/3 | 98 | 3.38 | 1.05 | 4.259 *** | <0.001 |

| 2/4 | 87 | 2.72 | 1.07 |

| Situation | Count | Mean | Standard Deviation | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPCP | 1/2 | 97 | 3.36 | 1.02 | 3.119 ** | 0.001 |

| 3/4 | 88 | 2.84 | 1.21 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy retention period policies | PRPP1 | −0.076 | 0.855 | 0.110 | 0.208 | 0.062 |

| PRPP2 | −0.068 | 0.881 | 0.207 | 0.199 | 0.017 | |

| PRPP3 | −0.024 | 0.808 | 0.181 | 0.300 | 0.129 | |

| PRPP4 | −0.077 | 0.879 | 0.173 | 0.219 | 0.088 | |

| Privacy information sharing policies | PPCP1 | −0.121 | 0.294 | 0.271 | 0.818 | 0.078 |

| PPCP2 | −0.188 | 0.281 | 0.226 | 0.822 | 0.086 | |

| PPCP3 | −0.107 | 0.251 | 0.207 | 0.847 | 0.096 | |

| PPCP4 | −0.155 | 0.218 | 0.247 | 0.829 | 0.142 | |

| Privacy benefits | PIT1 | −0.077 | 0.189 | 0.824 | 0.265 | 0.182 |

| PIT2 | −0.024 | 0.202 | 0.823 | 0.235 | 0.160 | |

| PIT3 | −0.056 | 0.230 | 0.836 | 0.204 | 0.227 | |

| PIT4 | −0.008 | 0.099 | 0.853 | 0.190 | 0.173 | |

| Privacy risks | PRI1 | 0.783 | −0.026 | −0.131 | −0.112 | 0.023 |

| PRI2 | 0.832 | −0.046 | 0.118 | −0.099 | 0.083 | |

| PRI3 | 0.892 | −0.038 | −0.019 | −0.095 | −0.022 | |

| PRI4 | 0.849 | −0.053 | 0.053 | −0.056 | 0.015 | |

| PRI5 | 0.826 | −0.086 | −0.194 | −0.106 | 0.028 | |

| Willingness to disclose personal information | IPA1 | −0.040 | 0.052 | 0.238 | 0.130 | 0.819 |

| IPA2 | 0.146 | 0.035 | 0.162 | −0.007 | 0.790 | |

| IPA3 | −0.074 | 0.154 | 0.133 | 0.094 | 0.834 | |

| IPA4 | 0.082 | 0.021 | 0.081 | 0.105 | 0.806 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.651 | 3.39 | 3.306 | 3.257 | 2.861 | |

| Common variance (%) | 17.385 | 16.144 | 15.743 | 15.51 | 13.623 | |

| Cumulative variance (%) | 17.385 | 33.53 | 49.273 | 64.783 | 78.406 | |

| Latent Variables | Observed Variables | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | |||||

| Privacy retention period policies | PRPP1 | 1 | 0.833 | ||

| PRPP2 | 1.041 | 0.908 | 0.066 | 15.836 *** | |

| PRPP3 | 1.016 | 0.841 | 0.073 | 13.993 *** | |

| PRPP4 | 1.093 | 0.918 | 0.068 | 16.112 *** | |

| Privacy information sharing policies | PPCP1 | 1.014 | 0.905 | 0.057 | 17.877 *** |

| PPCP2 | 1.062 | 0.9 | 0.06 | 17.662 *** | |

| PPCP3 | 1.02 | 0.873 | 0.061 | 16.61 *** | |

| PPCP4 | 1 | 0.88 | |||

| Privacy benefits | PIT1 | 1 | 0.871 | ||

| PIT2 | 1.002 | 0.848 | 0.067 | 14.961 *** | |

| PIT3 | 1.021 | 0.886 | 0.063 | 16.131 *** | |

| PIT4 | 0.94 | 0.822 | 0.066 | 14.194 *** | |

| Privacy risks | PRI1 | 0.967 | 0.725 | 0.091 | 10.598 *** |

| PRI2 | 1.035 | 0.782 | 0.089 | 11.693 *** | |

| PRI3 | 1.071 | 0.885 | 0.078 | 13.706 *** | |

| PRI4 | 1.082 | 0.81 | 0.088 | 12.241 *** | |

| PRI5 | 1 | 0.807 | |||

| Willingness to disclose personal information | IPA1 | 1 | 0.836 | ||

| IPA2 | 0.809 | 0.717 | 0.08 | 10.085 *** | |

| IPA3 | 1.005 | 0.797 | 0.089 | 11.349 *** | |

| IPA4 | 0.897 | 0.716 | 0.089 | 10.067 *** | |

| PRPP | PPCP | PIT | PRI | IPA | Average Variance Extracted | Rho_A | Composite Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRPP | 0.908 † | 0.824 | 0.933 | 0.929 | ||||

| PPCP | 0.566 | 0.919 † | 0.844 | 0.940 | 0.938 | |||

| PIT | 0.445 | 0.549 | 0.904 † | 0.817 | 0.929 | 0.925 | ||

| PRI | −0.163 | −0.287 | −0.137 | 0.844 † | 0.712 | 0.917 | 0.900 | |

| IPA | 0.214 | 0.265 | 0.415 | 0.026 | 0.834 † | 0.695 | 0.871 | 0.854 |

| PIT | PRI | IPA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRPP | 0.040 | 0.000 | - |

| PPCP | 0.193 | 0.060 | - |

| PIT | - | - | 0.156 |

| PRI | - | - | 0.007 |

| Paths | S.E. | t Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| privacy retention period policies → privacy risks | −0.000 | 0.108 | −0.003 | 0.9976 |

| privacy retention period policies → privacy benefits | 0.198 | 0.074 | 2.683 | 0.007 ** |

| privacy information sharing policies → privacy risks | −0.287 | 0.102 | −2.815 | 0.004 ** |

| privacy information sharing policies → privacy benefits | 0.437 | 0.072 | 6.100 | 0.000 *** |

| privacy risks → willingness to disclose personal information | 0.084 | 0.100 | 0.840 | 0.400 |

| privacy benefits → willingness to disclose personal information | 0.426 | 0.085 | 5.006 | 0.000 *** |

| Hypothesis | Test Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | An increased perception of privacy risks will negatively impact the willingness to disclose personal information. | reject |

| Hypothesis 2 | An increase in privacy benefits will positively impact the willingness to disclose personal information. | accept |

| Hypothesis 3 | Perceived shorter personal information retention periods will have a negative effect on perceived privacy risk. | reject |

| Hypothesis 4 | Perceived restriction of personal information sharing with third party companies will have a negative effect on perceived privacy risk. | accept |

| Hypothesis 5 | Perceived shorter personal information retention periods will have a positive effect on perceived privacy benefits. | accept |

| Hypothesis 6 | Perceived restriction of personal information sharing with third party companies will have a positive effect on perceived privacy benefits. | accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, S.J.; Lee, H.J. Unravelling the Effects of Privacy Policies on Information Disclosure: Insights from E-Commerce Consumer Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010049

Baek SJ, Lee HJ. Unravelling the Effects of Privacy Policies on Information Disclosure: Insights from E-Commerce Consumer Behavior. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Seung Jun, and Hong Joo Lee. 2025. "Unravelling the Effects of Privacy Policies on Information Disclosure: Insights from E-Commerce Consumer Behavior" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010049

APA StyleBaek, S. J., & Lee, H. J. (2025). Unravelling the Effects of Privacy Policies on Information Disclosure: Insights from E-Commerce Consumer Behavior. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010049