The Evolution of Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading: A Perspective of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading

2.2. Price Discrimination and Value Co-Creation

2.3. Price Discrimination and Platform Corporate Social Responsibility

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

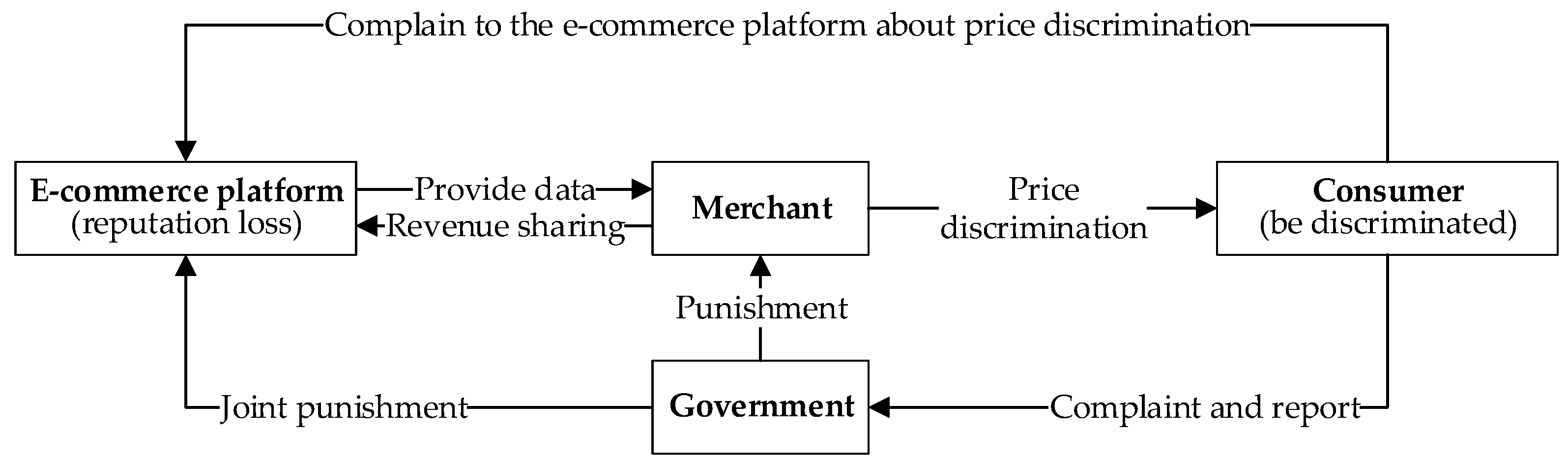

3.2. Problem Description and Conceptual Model

3.3. Model Assumptions

3.4. Model Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Stability Analysis of Evolution Strategies

4.2. Evolutionary Simulation Analysis

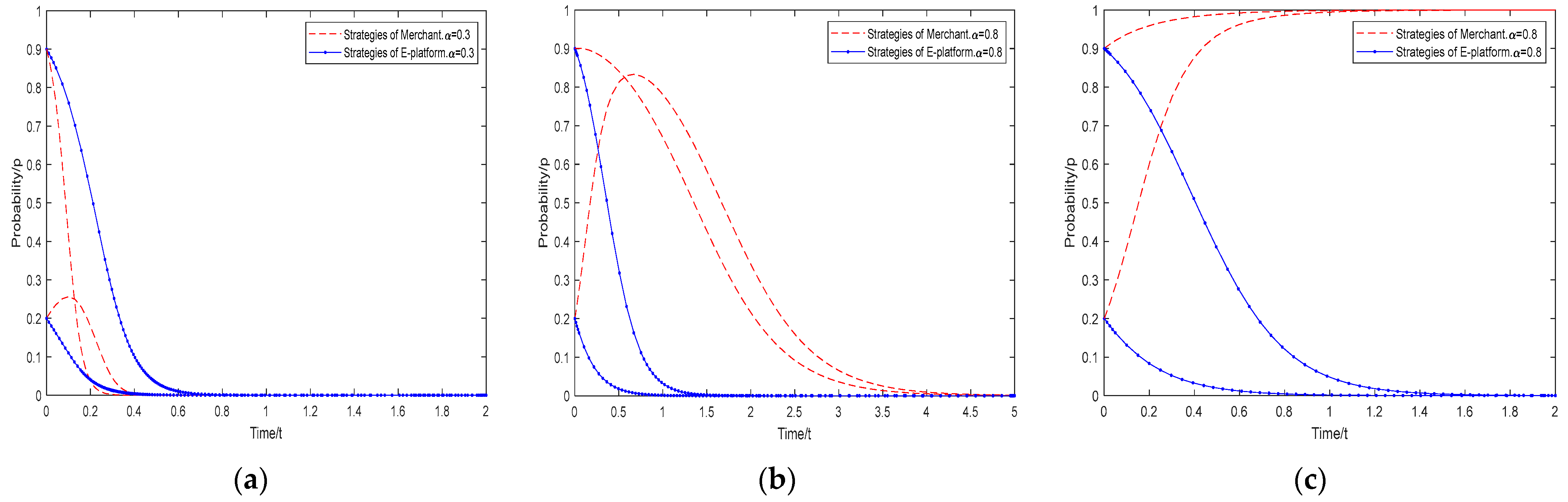

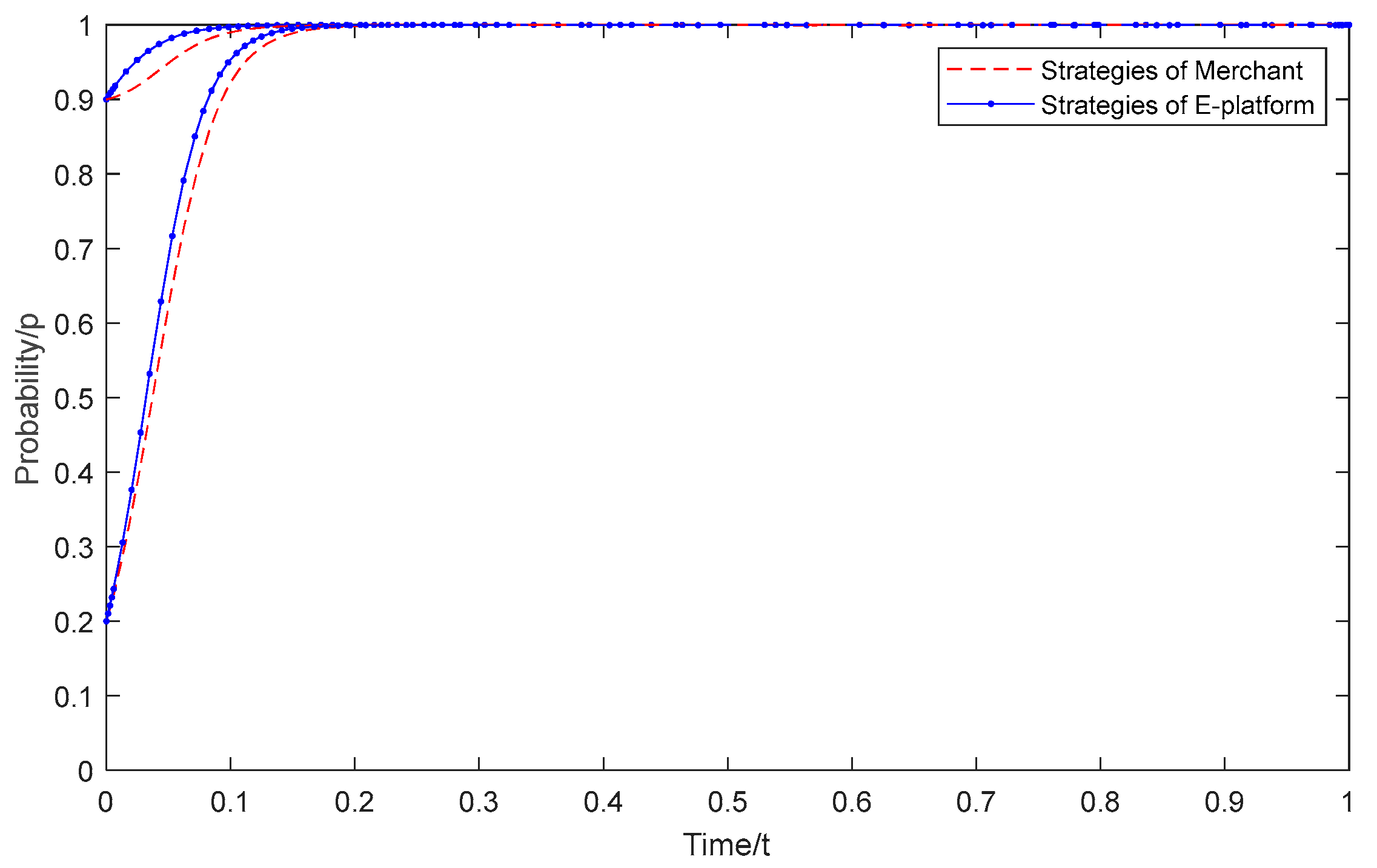

4.2.1. Low Reputational Losses and Punishments for Both Players

4.2.2. High Reputational Losses and Punishments for Merchants

4.2.3. High Reputational Losses and Punishments for E-Commerce Platform

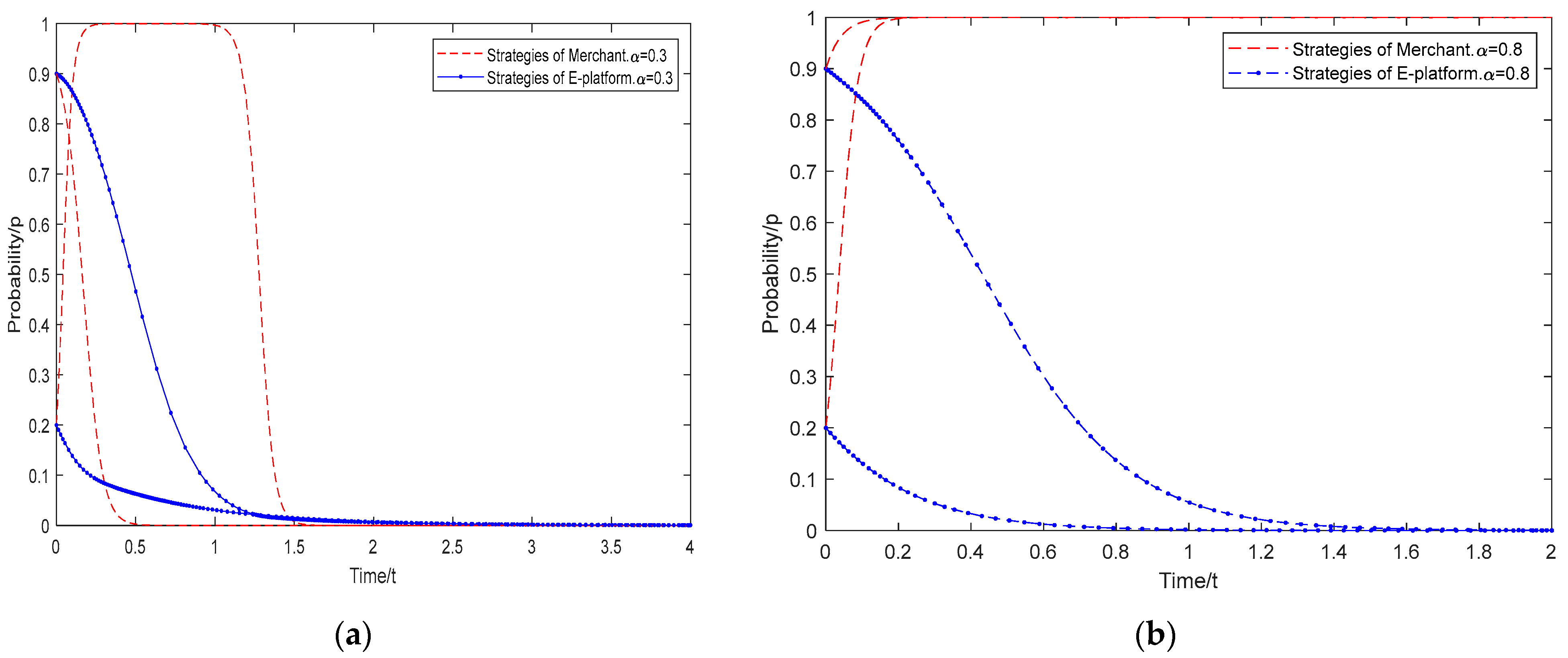

4.2.4. High Reputational Losses and Punishments for Both Players

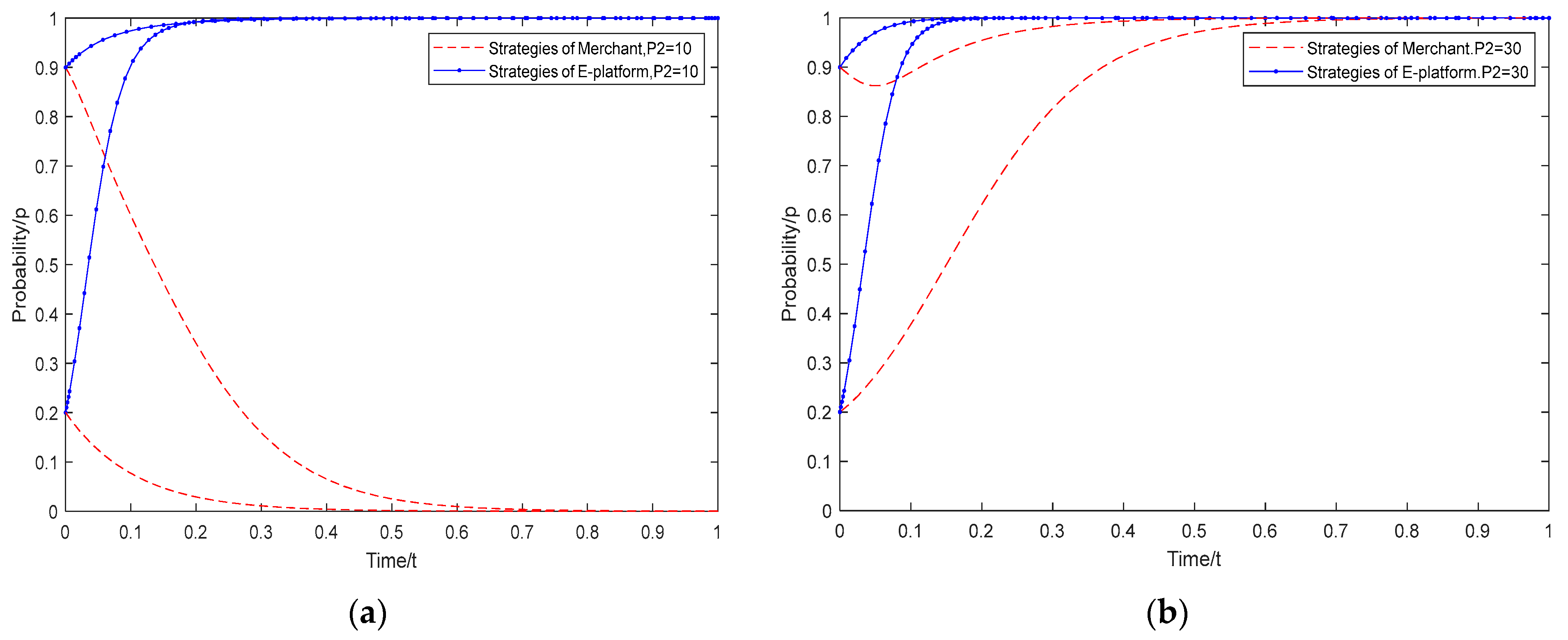

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—What is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Mora, D.; Cirqueira, D.; Helfert, M.; Bezbradica, M.; Werth, D.; Weitzl, W.J.; Riedl, R.; Auinger, A. Enhancing brick-and-mortar store shopping experience with an augmented reality shopping assistant application using personalized recommendations and explainable artificial intelligence. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; He, N.; Miles, I. Live Commerce Platforms: A New Paradigm for E-Commerce Platform Economy. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Tian, N.; Blankson, C. Big Data, Marketing Analytics, and Firm Marketing Capabilities. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Rao, J.; Wan, L.Y. The digital economy, enterprise digital transformation, and enterprise innovation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ma, Z. How do consumers choose offline shops on online platforms? An investigation of interactive consumer decision processing in diagnosis-and-cure markets. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, J. Why online personalized pricing is unfair. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y. Research on the Regulation of Algorithmic Price Discrimination Behaviour of E-Commerce Platform Based on Tripartite Evolutionary Game. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, S. Profitability of behavior-based price discrimination. Mark. Lett. 2023, 34, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y. The Impact of Algorithmic Price Discrimination on Consumers’ Perceived Betrayal. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 825420. [Google Scholar]

- Steppe, R. Online price discrimination and personal data: A General Data Protection Regulation perspective. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2017, 33, 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolinski, M. Dialogue on Price Gouging: Price Gouging, Non-Worseness, and Distributive Justice. Bus. Ethics Q. 2009, 19, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Research on Anti-Monopoly Regulations Against Algorithmic Price Discrimination. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 14, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M. Supervision Strategy Analysis on Price Discrimination of E-Commerce Company in the Context of Big Data Based on Four-Party Evolutionary Game. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2900286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Song, M.; Jing, L. Let your algorithm shine: The impact of algorithmic cues on consumer perceptions of price discrimination. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Gu, Q.; He, X. Selection of Sales Mode for E-Commerce Platform Considering Corporate Social Responsibility. Systems 2023, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Ding, L.; Wang, C. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Extra-Role Behavior. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1895598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.J.A.; Pereira, R.H.; Coelho, M.A.G.M. User Reputation on E-Commerce: Blockchain-Based Approaches. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jia, W. Research on Price Discrimination Behavior Governance of E-Commerce Platforms—A Bayesian Game Model Based on the Right to Data Portability. Axioms 2023, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liu, S. Ripping off regular consumers? The antecedents and consequences of consumers’ perceptions of e-commerce platforms’ digital power abuse. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—The misassumptions about contributions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, V.; Salimath, M.S. Co-creation of value in Platform-Dependent Entrepreneurial Ventures. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, J.; Wei, X. Effects of relational embeddedness on users’ intention to participate in value co-creation of social e-commerce platforms. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Zhou, L. The effect of image enhancement on influencer’s product recommendation effectiveness: The roles of perceived influencer authenticity and post type. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Eastin, M.S. Birds of a feather flock together: Matched personality effects of product recommendation chatbots and users. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, R.; Guan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, T. The influence of digital platform on the implementation of corporate social responsibility: From the perspective of environmental science development to explore its potential role in public health. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1343546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Shen, Q. A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) study on the formation mechanism of Internet platform companies’ social responsibility risks. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, X.; Ahsen, M.E.; Wattal, S. The Societal Impact of Sharing Economy Platform Self-Regulations—An Empirical Investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2022, 33, 1303–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, B. Strategy Analysis of Multi-Agent Governance on the E-Commerce Platform. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Samara, G.; Lu, J. Governance of corporate social responsibility: A platform ecosystem perspective. Manag. Decis. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Tianshan, M.; Rehman, S.A.; Sharif, A.; Janjua, L. Evolutionary game of end-of-life vehicle recycling groups under government regulation. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nałęcz-Jawecki, P.; Miękisz, J. Mean-Potential Law in Evolutionary Games. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 028101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrankić, I.; Herceg, T.; Pejić Bach, M. Dynamics and stability of evolutionary optimal strategies in duopoly. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 29, 1001–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyls, K.; Nowé, A. Evolutionary game theory and multi-agent reinforcement learning. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2005, 20, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, J.; Xu, F.; Jin, T.; Xiang, W. Reward and Punishment Mechanism with weighting enhances cooperation in evolutionary games. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2022, 607, 128165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Tao, C. Evolutionary game of platform enterprises, government and consumers in the context of digital economy. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y. Research on Credit Regulation Mechanism of E-commerce Platform Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2024, 33, 330–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.; Poort, J. Online Price Discrimination and EU Data Privacy Law. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Merchant | E-Commerce Platform | |

|---|---|---|

| Supervision | Collusion | |

| Integrity (x) | R1 R3 − (C2 + C3) | R1 R4 − C4 |

| Discrimination (1 − x) | R2 − (P1 + P2 + L1) R3 − (C2 + C3) − (P3 + L2 − P2) | R2 − α(P1 + P2 + L1) R4 − C4 − α(P3 + L2 − P2) |

| Equilibrium Point | a11 | a12 | a21 | a22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O (0,0) | R1 − R2 + α(P1 + P2 + L1) | 0 | 0 | R3 − R4 − (C2 + C3 − C4) + (1 − α) (P2 − P3 − L2) |

| A (1,0) | −[R1 − R2 + α(P1 + P2 + L1)] | 0 | 0 | R3 − R4 − (C2 + C3 − C4) |

| B (0,1) | R1 − R2 + (P1 + P2 + L1) | 0 | 0 | −[R3 − R4 − (C2 + C3 − C4) + (1 − α) (P2 − P3 − L2)] |

| C (1,1) | −[R1 − R2 + (P1 + P2 + L1)] | 0 | 0 | −[R3 − R4 − (C2 + C3 − C4)] |

| E (x*, y*) | 0 | M | N | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Guo, X.; Su, W.; Fu, G. The Evolution of Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading: A Perspective of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1907-1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030094

Ma Y, Guo X, Su W, Fu G. The Evolution of Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading: A Perspective of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(3):1907-1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030094

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Ying, Xiaodong Guo, Weihuan Su, and Guo Fu. 2024. "The Evolution of Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading: A Perspective of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 3: 1907-1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030094

APA StyleMa, Y., Guo, X., Su, W., & Fu, G. (2024). The Evolution of Price Discrimination in E-Commerce Platform Trading: A Perspective of Platform Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(3), 1907-1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030094