Abstract

Over recent years, social commerce has evolved into a powerful segment of e-commerce, creating new opportunities for brands of all types and sizes. However, if social commerce is to continue to grow and deliver the many benefits it promises, it must address a number of key challenges, including privacy, trust, and ethical concerns. This paper explores the extent to which privacy issues affect the attitudes and behaviours of social media platform (SMP) users towards social commerce, and investigates whether these attitudes and behaviours are a function of cultural context. The approach adopted for the research is a two-stage method, which initially uses semi-structured interviews of social-commerce users to identify their key privacy concerns. These concerns are then used to develop, using the theory of reasoned action (TRA), a structural model that facilitates the formation of hypotheses which relate users’ attitudes to privacy to subsequent behaviour. This model is assessed by analysing the responses to a questionnaire from a large sample of participants. This allows us to evaluate the general accuracy of the model and to compare culturally distinct subgroups (Saudi vs. Chinese) using partial least-squares analysis. Results show good support for all of our hypotheses and indicate that there are clear cultural effects. One of these effects is the inadequacy of privacy policies implemented by SMP providers, regarding culturally specific ethical concerns.

1. Introduction

Social commerce is defined as the buying and selling of goods or services directly within a social media platform (SMP) [1,2,3]. As the entire purchase process is completed without requiring the buyer to be concerned when leaving the SMP, it is different from (and a subcategory of) e-commerce, where interactions are managed from business websites and other digital platforms such as a unique app. Social commerce therefore includes examples such as adverts included in a social media feed that are “shoppable” (directly clickable to make a purchase), posts by influencers that are similarly shoppable, and videos or other media that may not obviously be adverts but may link directly to a dedicated e-commerce platform. An influencer’s vlog may feature a “haul” of items that they have acquired, and the viewer may be able to click directly to purchase some of these items. While the concept of social commerce has grown rapidly in recent years, in terms of consumer awareness and use, its roots can be traced back to 2005, where marketing promotions could be found on the early web services provider, Yahoo! [4,5,6,7].

The recent growth of social commerce is a result of a variety of factors, including the development of Web 2.0 applications [1,5,8,9], which facilitate interaction between consumers and businesses [5,6,9] and which allow users to generate their own content [8,10]. This new and evolving environment offers businesses a range of value-adding opportunities, including more effective deployment of digital marketing strategies [10], improved customer support [11,12], and the benefits of brand co-creation [13].

The sharing of information is therefore fundamental to the success of social commerce. This success is determined by social media users’ willingness to engage in activities such as posting about their buying experiences or retweeting the promotional messages of a particular brand [2,14]. However, while social commerce is growing in popularity, there is evidence that this growth may be limited by privacy concerns [15,16]. This is because consumers’ personal information can be exposed to a variety of risks, such as unauthorised access and misuse by social media providers and third parties such as cybercriminals [17]. These potential privacy threats can strongly impede social sharing. A key question, therefore, is the extent to which concerns about privacy affect consumers’ social interaction behaviour and purchasing decisions within the context of social commerce. The related question of whether, and to what extent, these concerns are correlated with cultural context is particularly important.

This paper sets out to explore these key questions. While there are a number of studies that examine the general question of online privacy [18], there are very few that seek to provide insights on the effects of information privacy on social commerce and the impact of cultural factors. The intention of this paper is to make a contribution towards filling this gap by addressing the following questions:

RQ1: What are the critical privacy factors that have a significant influence on consumers’ engagement with social commerce?

RQ2: To what extent are these critical privacy factors impacted by cultural context?

To provide insights into these questions, we deploy the theory of reasoned action (TRA) [19], which focuses on the role of attitudes and intentions in influencing behaviour. This is used to investigate the factors that condition behaviours in the field of social commerce. In doing so, we develop a model that allows us to interpret these factors in the light of cultural context. A deeper understanding of how individuals perceive privacy issues will lead to valuable insights for businesses and consumers alike.

2. Literature Review

An individual’s concerns regarding information privacy are a function of their perceptions and attitudes towards how their information is used and shared with others [12,16,20]. Typically, their concerns will be influenced by external factors such as their profession, cultural context, and national legislation [8,21,22]. Personality and experience are also likely to play a significant role [20,23,24]. Therefore, attitudes and opinions towards the collection and use of personal data are likely to vary widely within a given population.

The quantification of information privacy concerns has been studied by many researchers. Often, this takes the form of a single-dimensional measurement model [11,25]. While this model can work as a general indicator of privacy concerns, it is not nuanced enough to differentiate between different aspects of concern. To address this, Smith et al. [10] developed a multidimensional scale called CFIP (concern for information privacy) which uses 15 psychometric constructs to measure privacy concerns across four different dimensions: data collection, improper access, unauthorised secondary use, and errors. The validity and effectiveness of this measurement tool has been confirmed by Stewart and Segars [26]. The CFIP model has been successfully employed across a wide range of fields [27,28]. However, the fact that its basic dimensionality is neither absolute nor static has been clearly demonstrated in many ways, including the growth in global internet engagement, changes in the way that businesses are run, and the ability of consumers to control collection and use of personal data [10]. This leads to clear limitations in the use of the CFIP model.

Efforts to address these limitations have led to the introduction of alternative models of measurement. These models have moved away from the use of psychometric factors to the use of behavioural factors. They have also encountered theoretical difficulties, such as the fact that an individual’s behaviour often varies between different social media contexts. However, models have emerged that are designed to take these factors into account. Aghasian et al. [13], for example, developed a system that factors in the fact that users may engage with different social networks in different ways, while Papaioannou et al. [29] found that users faced with “social threats” behaved differently from users faced with “organisational threats”. All these attempts to measure privacy concerns have demonstrated that it is a complex parameter, one of several which affect behaviour.

Another privacy-related factor that affects consumers’ willingness to engage with SMPs is the extent and depth of their awareness of service providers’ privacy policies [30,31]. While it has been claimed that there is a positive correlation between the knowledge of the policy and willingness to share information, it is also claimed that most users never familiarise themselves with their SMP’s terms of service or privacy policies [30,31,32]. This leads to the superficially paradoxical situation whereby many users claiming to be concerned over privacy show little regard for it in practice. This contradiction between attitude in theory and behaviour in practice seems to extend to all subgroups of users. It has been shown by Salahshour et al. [32], for example, that academics rarely read the privacy policies of their networking systems, while similar results have been found for more general users [30]. One of the aims of this paper is to explore the importance of privacy policies to users and the extent to which cultural context impacts this.

The impact of culture on privacy concerns is also an important issue, and there is considerable evidence in the literature that this can be significant. Although, as shown by Cassell and Blake [33], using Hofstede’s [34] model, this impact tends to vary from country to country, there are also instances where there are regional cultural differences within a given country. However, cultural differences can also exist within a given population that has no clear regional divisions between cultures [35,36,37,38,39]. Such a situation exists, for example, in Saudi Arabia, where there are cultural differences between the Saudi and Chinese elements of the population.

An exploration of the different attitudes and behaviours, with respect to privacy, of these two subgroups is one of the principal aims of this research. According to Alsolamy [40], there is a deeply rooted relevance, within the Saudi culture, of the concept of ‘privacy’, a term which may take on a different meaning in other cultures. This view is broadly echoed by Cannataci [36], who has traced the notion of privacy to scriptural sources. This implies that the importance of privacy is likely not to be confined to any specific subgroup of social media users but extends across the different populations of users.

The proposition that privacy concerns are of particular significance in Muslim societies is reinforced by the findings of Abokhodair et al. [41], who showed that cultural values profoundly affect social media use, especially among the female population. Abokhodair et al. [41] argue that this is partly a result of the collectivist nature of these societies, in which social norms are often defined and enforced through shared beliefs and practices. It follows from this that individuals who are not part of this culture are likely to have different attitudes towards privacy [42,43]. We would therefore expect the Chinese elements of a population to show different behaviours to Saudi elements, in terms of privacy. This paper explores this expectation.

3. Research Method

This research uses a two-stage method approach. This was chosen because the use of a single method (quantitative or qualitative) can result in less nuanced and comprehensive findings. The study deploys two separate stages: (1) exploratory and (2) confirmatory.

The exploratory stage uses a qualitative approach (interviews) to provide a deeper understanding of the key privacy factors that impact social commerce engagement. The results of these interviews were used, together with an analysis of the literature and previous research, to establish the study’s research model and hypotheses (see Section 4).

The confirmatory stage allows us to test the hypothesis that there is a relationship between observed variables and their underlying constructs. For this phase, a questionnaire, based on results from the exploratory phase, was used. In addition to testing and validating the research model, this element of the study also allowed us to compare attitudes and behaviours of two cultural groups (Saudi and Chinese). This is further described in Section 5.

It is important to acknowledge that, prior to commencing the study, the planned methodology was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at King Saud University. All participants were asked to read and sign an informed consent form, which confirmed that any and all information provided would be fully anonymous and kept in confidence. It also confirmed that all data would be used solely for purposes of the study and that data would be destroyed upon completion of the study. All participants were advised that they could withdraw at any time.

4. Exploratory Stage

4.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

A total of 25 social commerce users were interviewed, with a focus on understanding the key privacy factors that influence consumers’ engagement with social commerce. Each participant was an experienced social media user with between one and ten years’ experience of using SMPs and social commerce. Participants were also diverse in their professions as well as their cultural background. The sample size of 25 was considered sufficient for meaningful results, based on the concept of data saturation, defined by Saunders et al. [44]. After this point (20 interviews), no new information, views, or insights were provided by interviewees. Each interview lasted a similar time (one hour), followed the same format, and was recorded for later transcription and analysis. Table 1 provides a broad demographic profile of the sample.

Table 1.

Summary of participant profiles.

4.2. Results

Here, we describe the results of the exploratory stage, and develop the basis for the model and research hypotheses.

An analysis of the interviews was carried out using thematic analysis. In order to ensure the reliability and validity of the results, and to minimise possible bias, a triangulation approach, based on demographics, was employed. This resulted in the identification of three distinct aspects of information privacy that significantly impacted SMP users’ decision to engage in social commerce. These are as follows: Awareness and Acceptance of Privacy Policy (AAPP), Collection & Use of Personal Information (CUPI) and Personal Control of Private Information (PCPI). These factors are defined as follows:

- AAPP—the degree to which a user believes that SMP privacy statements are relevant, important, and effective in protecting their private information against abuse.

- CUPI—the degree to which a user is concerned that private information collected by the service provider will be abused or passed to third parties.

- PCPI—the degree to which a user believes they have control over private information collected by the service provider.

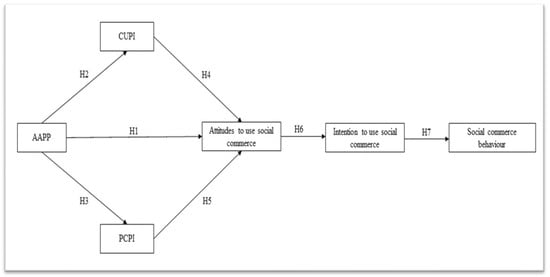

The results from stage one of the study allow us to propose a model in which three factors (CUPI, PCPI, and AAPP) are central to a user’s engagement in social commerce and, ultimately, their behaviour. Figure 1 shows this model based on the theory of reasoned action (TRA) [19]. In the following subsections, we discuss the effects of each of these factors and how hypotheses can be derived from them.

Figure 1.

Research model. Note: H1-7 mean hypothesis.

4.2.1. The Effect of AAPP on Readiness to Engage in Social Commerce

There are several previous studies which show that concern about the risk of abuse of personal data is impacted by users’ awareness of privacy policies and perception of their effectiveness [30,31]. The literature also shows that privacy policy awareness affects users’ intention and, consequently, their readiness to use social commerce [45,46] and make online transactions [47]. Similarly, the contrary is also true—that a lack of awareness of privacy policies has a negative impact on readiness to share personal information [17]. These findings were reflected by the findings in the current study, as illustrated by the following extracts from interviews.

“You know … I only use social media platforms when I am confident that my information is secure and that their privacy practices are trustworthy … I need to be educated correctly about how information sharing policies are used but this is not always the case.”

“I have experience with social commerce, so, for me to choose which information to share with these sites [social media sites], … privacy policies are important. Such regulations, in my opinion, ought to be precise, efficient, and tailored to each nation … also based on different culture and context.”

“For me, I usually try to make sure to understand the privacy policies that apply to my information I provide these sites [social media sites] before I agree to the terms and conditions.”

“The information I decide to provide is impacted by policies. The effectiveness of privacy policies is not sufficiently understood in social media environments, which could cause hesitation. You know, we need to be aware of the policies that are supposed to ensure protection of our personal data as users of social networks for the aim of sharing knowledge. You know, are social media sites’ privacy policies known to you? This is a place for question … except for the attorneys who work for these firms, no one else on earth is aware of these facts. For you, also me, have you ever tried reading their statements regarding privacy practices … I don’t think so.”

Given this, it is reasonable to assume that users will be more positive towards information sharing if they are confident that their data will not be abused or shared with other, undeclared, parties. This leads to the following three hypotheses:

H1.

AAPP influences users’ attitudes towards engaging with social commerce.

H2.

AAPP impacts users’ CUPI level when engaging with social commerce.

H3.

AAPP influences users’ requirement for PCPI when using social commerce.

4.2.2. The Effect of CUPI on Readiness to Engage in Social Commerce

Data collection and use is a principal concern of all social media users, especially when transactions are involved [48,49]. The findings from the exploratory stage of this study show that this is particularly true for social commerce users. Typical comments included the following:

“I find it difficult to use websites when they collect too much personal information, you know that, because I worry that it might be sold to other businesses … getting personal information really influences whether or not I utilize social media platforms. If we [users] understood exactly how it was being utilized, it wouldn’t be as concerning, but we typically don’t … we are unsure as to whether or not we can rely on their data privacy rules. If I anticipate that my personal information may be utilized negatively, I am hesitant to share it.”

“… my decision to reveal my information is influenced by this, which is a significant factor ….”

“You know, collection of personal information for me is a crucial factor that influences my choice to share my information. I consider the privacy policies when deciding what details I give to these websites [social media sites]. Such regulations, in my opinion, ought to be precise, efficient, and tailored to each nation and culture.”

“When determining what information to share with various websites, I evaluate privacy policies. In my opinion, such regulations should be clear, effective, and suited to my culture.”

These views have been shown to be common across all online services [50]. To reflect the findings of the exploratory study and literature review, with respect to privacy concerns, we hypothesise the following:

H4.

CUPI influences users’ attitudes and intention to engage with social commerce.

4.2.3. The Effect of PCPI on Users’ Willingness to Engage in Social Commerce

Several previous studies have shown that perceived control of information privacy has a significant effect on user behaviour [51]. Specifically, and relevant to this study, findings show that perceived control may facilitate information sharing [52]. Given these findings, it is reasonable to conclude that an increased perception of control will lead to more positive attitudes towards social marketing, for which information sharing is critical. This conclusion is strongly supported by the results of the exploratory stage of this study. In the words of the study participants,

“For me, I will only be willing to disclose my information if I am given absolute control over it and am regularly informed about how it will be used. You know, in my opinion it is crucial that consumers have choice over how their personal information is utilized, especially given how widely social networking platforms have been adopted and used … that control is absent from the majority of social media platforms, as far as I can tell.”

“That control is absent from the majority of social media platforms … it is crucial not knowing how their personal information is used … I see there is no absolute of control over it.”

When social media users’ control over private information is perceived to be high, their perception of data security also rises [45]. It follows that the higher a user’s perceived control, the higher their readiness to share information and therefore participate in social marketing. Again, this is supported by the findings of this study, as demonstrated by the comments of one participant:

“All uses of the person’s personal information must have their consent, which is crucial … this should be link with a modification option and an opt-in/opt-out choice should also be available and clear to them.”

“The use of social commerce will undoubtedly be impacted by clarity on these issues … I only use websites whose practices make me feel confident that they will consider user privacy as a resource to be used by the user, not as their own property.”

“In my opinion, the use of social commerce will undoubtedly be impacted by lack of personal control to private information … for me, I only use websites that let me have a voice in how my data is handled so that I can have some degree of realistic control over it … I only use websites that practices make me feel confident that they will consider user privacy.”

To better understand the effects of perceived control on information sharing, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

PCPI affects users’ attitudes toward engagement with social commerce.

4.2.4. The Effect of Attitude and Intention on Social Commerce Behaviour

Developed in its current form by Fishbein and Ajzen [19] in 1975, TRA seeks to enable the understanding of how attitudes and intentions are related to behaviour. When this relationship is understood, it becomes possible to predict behaviours as a function of attitudes with greater accuracy. In the context of the current research, TRA is a useful tool, as individuals with a higher intention to engage in social commerce will be more likely to translate this intention into behaviour. This is illustrated by the following extracts from the research.

“It took me quite a while to get serious about social media, as I didn’t really trust the social media sites when it comes to the use of personal information.”

“The idea of making use of other people’s experience when purchasing goods and services has always seemed a good idea to me, which is why I started to become involved in social commerce.”

“I got involved in social commerce … I have always thought it was a good idea to draw on other people’s experiences when making buy … I didn’t really trust social media sites when it came to the usage of personal information.”

To better understand the effects of attitude and intention on social commerce behaviour, we therefore hypothesise the following:

H6.

Attitudes toward using SMPs will influence users’ intention to engage in social commerce.

H7.

Intention to engage in social commerce will influence users’ social commerce behaviour.

4.2.5. The Role of Culture in Willingness to Engage with Social Commerce

As noted above, one of the principal aims of this study is to investigate whether there is a difference between Saudi and Chinese members of a population when it comes to issues of information sharing and engaging with social media. The following extracts from interviews indicate, firstly, that our participants see cultural differences as important:

“I emphasize the need of adjusting and harmonizing the rules and conditions of use. You know … this will support a more upbeat outlook growth of social commerce. What pertains to the EU might not apply to Arab and or Asian … I’m considering this as very crucial point, because each nation has its own culture … what applies to one might not apply to other.”

“As I mentioned, for social commerce to grow, cultural aspects are important, for my primary worry is that these privacy regulations are generally created to conform to western legal systems and are therefore somewhat general. To better serve the requirements of different culture and religion … in my opinion it would be better if were country or context specific.”

“In my opinion … due to the fact that all cultures are different, social media sites can make it challenging for certain people to build trust. Cultural variations pose some serious challenges for using social media for social commerce.”

In the following extracts, we see, further, that there appear to be distinct differences in attitude between our two groups:

[Participant from Chinese group:] “I feel that, for Chinese people generally, talking about myself, I don’t pay much attention to or give much thought to privacy … due to some specific circumstances in the society. I usually react rationally to privacy …”

[Participant from Chinese group:] “I’m less likely to be concerned about privacy, potentially for political and social reasons, but I’m also eager to exchange my personal information for free goods and customized advertisements. As someone who lived in Saudi, this might not be the case among Saudi citizens …”

[Participant from Chinese group:] “I choose to accept the privacy breach as being the usual because it is the price you have to pay for the convenience of internet shopping, but it can’t be too expensive.”

[Participant from Saudi group:] “In general, privacy and data-related issues are not new, and they are still relevant in today’s digitalized society, which is characterized by the accessibility of information. I believe that privacy is very important … and that no one will stop providers invading my privacy, as myself.”

[Participant from Saudi group:] “I used to take a lot of security measures to protect my privacy, such as creating a separate phone number just for making online transactions. As the volume of unwanted emails and texts rose, I concluded that they made a small but insignificant contribution to efficacy. Sincerely, I’m quite frustrated, but there’s nothing I can do but stop making online transactions.”

We discuss these differences in more detail later. Here, to better understand the role of culture in willingness to engage with social commerce, we hypothesise the following:

H8.

The impact of AAPP on users’ attitudes towards engaging in social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H9.

The impact of AAPP on users’ CUPI requirements when using social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H10.

The impact of AAPP on users’ PCPI requirements when using social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H11.

The CUPI impact on users’ attitudes toward using social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H12.

The perceived PCPI impact on users’ attitudes toward using social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H13.

The impact of attitudes toward using SMPs on users’ intentions to engage with social commerce differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

H14.

The influence of the intention to use social commerce on sharing behaviour differs between Saudi and Chinese users.

5. Confirmatory Stage

5.1. Questionnaire Development

There are many ways of developing questionnaires [53,54]. This study used a set of 25 items, developed from the interviews in stage one and the existing literature, to explore how information privacy concerns affect users’ decisions to engage in social commerce. Responses to each item were ranked using a five-point Likert scale. Although most items were created specifically for the study, some were adapted from existing scales that have been proven to be reliable (see Table 2). A pilot exercise of 72 social commerce users was carried out to ensure clarity to participants, and some adjustments were made in response to feedback.

Table 2.

Constructs; items with factor loadings and sources.

5.2. Content Validity Assessment

Before the data collection phase began, the questionnaire was validated as recommended by MacKenzie et al. [56] and Straub and Gefen [57]. To achieve this validation, a number of experts were asked to assess the validity of items in the survey [58]. While there is no universal agreement on the appropriate number of experts that should be used, most agree that three is sufficient [59]. In this case, ten experts were invited to participate, and seven returned completed surveys. As a result of the feedback from the experts, four items were removed from the initial questionnaire, bringing the total to 21 fully validated items.

5.3. Primary Data Collection

The participants in the study were selected using a random sampling strategy. The resulting sample was diverse in terms of gender, culture, and professional level, and all participants were active users of social media platforms and social commerce, with a range of experience. The questionnaire was distributed by email, and data were collected over a period of three months. A total of 385 valid questionnaires were used in the study. Table 3 summarises the key demographics of the sample.

Table 3.

Sample demographics—summary.

5.4. Testing the Measurement Model

To ensure accuracy and validity of the data analysis, several steps were taken. The data, for example, were checked for data entry errors using SPSS (v.21), and the information was fully checked for missing entries, as recommended by Hair et al. [60]. Further, to assess the internal consistency reliability and construct validity of the measurement model, a factor loading—using Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average varianc—was calculated [60]. Table 2 shows the results of the analysis and illustrates that each of the factor loadings meets or exceeds the criterion of 0.6. In addition, Table 4 shows that the CR and CA values exceed the criterion of 0.7, with AVE reaching more than 0.5 for each construct. The results of this analysis confirm both the convergent and discriminant validity, as well as the internal consistency reliability, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker [61]. In addition, since self-reported questionnaires were used as the basis for this part of the study, common method variance (CMV) could lead to lowered variable validity. This can affect the acceptance or rejection of a hypothesis [62]. To assess this possibility, each of the variables were analysed using SPSS. This showed that CMV was not a major issue and did not significantly impact the variables’ path coefficients.

Table 4.

Correlations, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE).

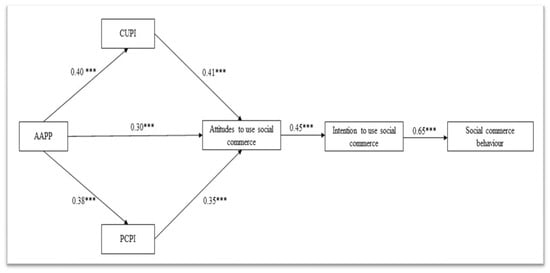

5.5. Results of Structural Model Evaluation

Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the psychometric properties of the measurement model, and the hypotheses were tested using the same approach. Estimations were made at this stage using the Amos (v.26) software package. The results are shown in Figure 2. These show that CUPI, PCPI, and AAPP all significantly influence attitudes towards social commerce (explaining 41.3% of variance). Attitudes towards social commerce also significantly influence intention towards social commerce (explaining 47.3% of variance), which consequently affects social commerce usage behaviour (explaining 62.5% of variance). The study findings also indicate that all hypotheses are fully supported. The t-values and standardised path coefficients of the model are presented in detail in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Research model. (Results of structural model evaluation using the whole sample. *** p < 0.01.)

Table 5.

Path coefficients and t-values for full sample.

Table 6 shows the goodness-of-fit indices for the structural model, meeting the recommended criteria by Hair et al. [60].

Table 6.

Goodness-of-fit indices.

5.6. Analysis of the Model Paths: Saudi and Chinese

The full dataset for this section of the study comprised 385 participants (266 Saudi and 119 Chinese). An analysis (using a multigroup partial-least-squares (SmartPLS 3) technique of the data, see Table 7) supports the hypotheses H8-H14. This suggests that differences exist between these groups in the context of attitudes and behaviours in information sharing. We contend that these differences are a result of cultural factors.

Table 7.

Standardised comparisons of paths between Saudi and Chinese.

6. Discussion

Today, social commerce is an increasingly important subcategory of e-commerce. It has several key drivers, including ease of purchase, improved brand engagement, and informational support and recommendations. However, there are also some factors which are limiting its growth. One of these is the question of online privacy—the question of user trust in the security of their personal information. As sharing private information is important within a social commerce context, it is essential that users have trust in the willingness and ability of social commerce service providers not to abuse this information.

Online privacy has been the subject of many e-commerce studies in recent years [63,64,65]. However, while research such as that by Wang et al. [66] explores the effects of agency assurance—specifically privacy policies—on user engagement, there are no studies that investigate how privacy issues such as Awareness and Acceptance of Privacy Policy (AAPP), Collection & Use of Personal Information (CUPI), and Personal Control of Private Information (PCPI) affect the attitudes of users, and how these attitudes affect the intent to engage in social commerce and consequent behaviours. In particular, there are few studies that explore the effect of cultural context on the intent to engage with social commerce. This study contributes to the current literature by seeking to address both of these issues—that is, the importance of privacy from the user’s perspective and the impact of cultural factors.

This research also differs from most previous studies [1,4,23,67], by using data from comprehensive, face-to-face interviews, together with findings from the most relevant current literature, to create a research model that can be used to explain privacy concerns from the viewpoint of social commerce users. The study therefore contributes a more comprehensive understanding of how privacy concerns affect engagement with social commerce, by illuminating the significant influences of PCPI, CUPI, and AAPP in this context.

An example of this latter point is connected to CUPI—the individual’s perception of risk. The findings of this study show that the attitudes of users toward using social commerce are strongly influenced by CUPI, which consequently affects their behaviours to engage with social commerce. This reflects the argument of Jozani et al. [11] that, although, in general, SMPs aim to collect as much information as possible from users, the privacy of those users must be respected and protected, in order to reduce the perception of risk. Additionally, and equally importantly, respect and protection must be effectively communicated to the user; otherwise their perception will not change. Unless this is the case, levels of engagement with social commerce are likely to be impacted.

The results of the study also demonstrated that the attitudes of users towards engaging with social commerce are strongly influenced by PCPI. The findings show that perceived privacy on social commerce platforms is much more dependent on perceived control of shared information than actual control of information. The alternative to this would be that, in some subtle way, giving users more control, for example, could improve their perception of privacy even though they had not noticed (perceived) the change in control. Overall, it is unlikely that perceived privacy would be independent of perceived control in such a way. This is a valuable insight for service providers, as it provides an opportunity to more effectively manage privacy risks and build user trust (and therefore engagement) by developing and implementing PCPI tools. As Berings and Adriaenssens [59] suggest, by giving users a variety of options for managing their data, it may be possible to lower their perception of privacy risk.

If perceived privacy level varies with perceived control, it is natural to suppose that privacy concerns would vary with perceived control, if we assume it derives from perceived privacy in combination with the perceived importance of privacy. However, a finding by Mourey and Waldman [68] suggests that the perceived importance of privacy also varies with perceived control, which introduces some appearance of circularity. This may indicate a situation more like a feedback loop, where a complex construct composed of people’s perceptions of their degree of control, the degree to which their privacy is protected, and the very importance of privacy derive from continual interactions between these dynamic elements. The particular relevance of this to users in the Arab world is emphasised by Abokhodair [41], from whose work we can infer that the perceived importance of privacy, though it may be in a dynamic relationship with perceived control, is also conditioned by the cultural context of, in this case, Islam.

Another instrument which can be used to decrease perceived user risk is the privacy policy. Many of the participants in this study were convinced that privacy policies are essential to reducing the perceived risk of sharing information, while recognising that user understanding of these policies is rarely high. This point was illustrated by the views of many interviewees, examples of which are given in Section 4.2. Similarly, a significant strand of evidence and arguments in the literature suggests that the presence of privacy policies enhances consumer confidence and acceptance of online commerce and services, even though the policies are rarely read, let alone understood [67,68].

The issue of why users do not engage, at a detailed level, with privacy policies, while still believing that they have a significant role, is an important question. Mutambik et al. [42] suggest that one answer may lie with national regulatory systems. The regulatory framework around policies is often noted in the literature as a major influence on their content and usage because the privacy policies are often built around the US Federal Trade Commission’s Fair Information Practice Principles [17,69], and/or influenced by the GDPR and related European regulations [70]. Privacy regulations around the world are often modelled on the same principles. Users in jurisdictions with strong regulation may tend to feel that their interests are protected by these regulations and that the presence of the privacy policy is effectively an acknowledgement that the provider is aware of the need for compliance.

Conversely, where regulation is not considered to be strong, users may be less confident: Bellman et al. [71] found, across 38 countries, that participants from regions lacking privacy regulation were more concerned about the security of online transactions than those from regions with regulation. In these regions, we might anticipate that users will be more likely to engage with the content of privacy policies. Alternatively, they may find this to be intractable and instead simply recognise that their use of online services is high risk in terms of privacy and personal data.

In Arab countries, for example, at the time of data collection for this study, specific legislation for data protection was in its early stages. However, it is clear that our participants do not, in general, read and understand privacy policies; even if they did, this might not change the common view among them that the online environment is risky in ways that are hard to control. Faced with this risk, there seem to be limited options. One option might be to stop using online services altogether, but most people find this effectively impossible. Another option might be to proceed with caution, using services only when necessary and revealing as little information as possible. Another might be to stop worrying, behave as though the environment were safe, and hope that the consequences will not be too serious, which resembles being “in denial” about the risks. In these respects, perhaps there are similarities with other areas of recognisable large-scale risks associated with common behaviours, such as climate change, various health risks, etc. In such cases, responses vary: people may become very engaged and active or, on the other hand, feel that they have little effective agency or that the apparently necessary changes in behaviour simply cannot be faced.

In our study, we observe differences between the attitudes of our groups, as noted before, and we can now see that some of these reflect risk options in different ways. For example, there is some evidence that participants from the Chinese community are more pragmatically accepting that the sacrifice of personal data is inevitable:

[Participant from Chinese group:] “In my perspective, the loss of privacy is an unintended consequence of modern technology … we say in China if the water is excessively pure no fish can survive … Similarly, no online action is possible if no personal information is provided … so I decided to reduce my privacy.”

[Participant from Chinese group:] “There is no monitoring to check whether their [social commerce platforms] actions and statements are consistent. They don’t inspire much confidence in me. So I’d rather choose one [of these social commerce platforms] that at the very least provided me with some benefits, such as a reasonable price and more product options.”

On the other hand, participants from the Saudi community seem more frustrated, at least, by this situation:

[Participant from Saudi group:] “In general, privacy and data-related issues are not new, and they are still relevant in today’s digitalized society, which is characterized by the accessibility of information. I believe that privacy is very important … and that no one will stop providers invading my privacy, as myself.”

[Participant from Saudi group:] “There are so many social commerce platforms that it is nearly impossible to ensure that all of them take our personal information seriously and responsibly if there is no regulation … even if there is, I’m not sure how well it will be applied.”

These different attitudes to privacy are also reflected to some extent in views about privacy policies specifically. There seems to be a tendency for Chinese participants to see them as being of doubtful value in themselves and perhaps dependent on the regulatory environment to give them any effect.

[Participant from Chinese group:] “We’re [Chinese] less inclined to read the privacy statement and are less confident in it. I feel that, for Chinese people generally, talking about myself, I don’t pay much attention to or give much thought to privacy … due to some specific circumstances in the society. I usually react rationally to privacy … As a Chinese citizen, I feel that their government has the power to secure personal data and that companies will abide by the norms.”

[Participant from Chinese group:] “There is no monitoring to check whether their [social commerce platforms] actions and statements are consistent. They don’t inspire much confidence in me.”

On the other hand, Saudi participants perhaps feel that these policies are very important in principle but still lacking in clarity and enforcement.

[Participant from Saudi group:] “I get the feeling that they [the privacy policies of social commerce platforms] don’t want us to comprehend them. They merely include superficial information or things.”

This may suggest that, even within a given jurisdiction, different cultural groups can react in different ways to the relationship they perceive between SMC providers and the regulatory system, indicating that the roles of privacy policies, while still not necessarily very dependent on their content, may vary markedly for these groups. We may therefore expect to see significant differences in social commerce behaviour among these user groups. This is also discussed by Mutambik et al. [42], in relation to Abokhodair [41], where the potential significance of further cultural factors is emphasised, such as the role of gender, which we have not discussed here but which is widely recognised as a major factor in Saudi society. Also lacking a general and, especially, cross-cultural measure of risk perception [72], significant further work is necessary before we would be able to say clearly which factors might explain differences between our cultural subgroups.

7. Conclusions

This study has explored the issue of privacy concerns that influence consumers’ engagement with social commerce and the extent to which these concerns are a function of cultural context. In order to address these questions, the study identified three distinct factors which relate an individual’s privacy concerns to their engagement in social commerce). These are as follows: Collection & Use of Personal Information (CUPI), Personal Control of Private Information (PCPI), and Awareness and Acceptance of Privacy Policy (AAPP). It was found that each of these factors, individually and collectively, impact a person’s attitude towards sharing private information and—consequently—their engagement in social commerce. It was also found that attitudes towards privacy, and consequent use of social commerce, were significantly affected by cultural factors.

One key finding of the study concerns the user’s perception of privacy. The results of the research show that this is strongly impacted by the user’s perceived, as opposed to actual, level of control over their own information. This insight is of particular relevance and use for SMP service providers, as it means they can build consumer trust, and therefore positively affect engagement behaviours, not only by providing users with more control over their private information but, equally, by helping the users perceive the degree of control that they have. It has been argued that in the domain of environmental risk, good communication and developing a fuller understanding of the risk can substantially shift the public’s perception of risk [73]; perhaps the same is true for data risk, but it also seems likely that such communication and education will need to be sensitive to cultural factors.

One focus of this study has been on the implications for social commerce of cultural differences within a country. Our exploratory investigation revealed attitudinal differences between the Chinese and Saudi subgroups within the Saudi context, and our quantitative results showed that there is indeed a significant difference between these groups. Further research will be needed to characterise the nature of this difference more clearly, but at this stage, we can suggest that companies active in the field should look closely at their consumer groups and consider how to articulate their relationships, including privacy policies and communication strategies, in more sophisticated ways.

Future research may usefully develop the study of the effects of privacy concerns on user behaviour in social commerce, particularly in a cross-cultural context. This will undoubtedly lead to valuable implications for practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., J.L., A.A., J.Z.Z., and A.H.; methodology, I.M., A.A., and A.H.; validation, J.L., J.Z.Z., and A.H.; formal analysis, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, I.M., J.L., A.A., and J.Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R233), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Human and Social Researches) of King Saud University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions of privacy.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project (RSP2023R233), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baghdadi, Y. From E-Commerce to Social Commerce: A Framework to Guide Enabling Cloud Computing. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doha, A.; Elnahla, N.; McShane, L. Social Commerce as Social Networking. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, O. Social Networking Services and Social Trust in Social Commerce. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y. Social Commerce: A New Electronic Commerce. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Wuhan International Conference on e-Business, Wuhan, China, 26–27 May 2012; pp. 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N. Social Commerce Constructs and Consumer’s Intention to Buy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Haddad, H.; Al-Amad, A.H.; Rees, D.; Hajli, N. Investigating the Impact of Situational Influences and Social Support on Social Commerce during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Hu, C.; Chauhan, S.; Gupta, P.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Mahindroo, A. Social Commerce: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Directions. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 29, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M.J.; Bies, R.J. Consumer Privacy: Balancing Economic and Justice Considerations. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Dunfee, T.W. Toward a Unified Conception of Business Ethics: Integrative Social Contracts Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns about Organizational Practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozani, M.; Ayaburi, E.; Ko, M.; Choo, K.-K.R. Privacy Concerns and Benefits of Engagement with Social Media-Enabled Apps: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.J. Relationship Marketing in Consumer Markets: A Comparison of Managerial and Consumer Attitudes about Information Privacy. J. Direct Mark. 1997, 11, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghasian, E.; Garg, S.; Gao, L.; Yu, S.; Montgomery, J. Scoring Users’ Privacy Disclosure Across Multiple Online Social Networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 13118–13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajvidi, M.; Richard, M.-O.; Wang, Y.; Hajli, N. Brand Co-Creation through Social Commerce Information Sharing: The Role of Social Media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Benyoucef, M. Consumer Behavior in Social Commerce: A Literature Review. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 86, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Understanding Consumers’ Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce through Social Capital: Evidence from SEM and FsQCA. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. The Role of Privacy Policy on Consumers’ Perceived Privacy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutimukwe, C.; Kolkowska, E.; Grönlund, Å. Information Privacy in E-Service: Effect of Organizational Privacy Assurances on Individual Privacy Concerns, Perceptions, Trust and Self-Disclosure Behavior. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Gao, Y.-X.; Jia, Q.-D. The Role of Social Commerce for Enhancing Consumers’ Involvement in the Cross-Border Product: Evidence from SEM and ANN Based on MOA Framework. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N. Social Commerce and the Future of E-Commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, Y.-H.; Tan, F.T.C. A Cross-Cultural Perspective on the Blended Service Quality for Ride-Sharing Continuance. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibel, R.C.; Kracht, R. Social Commerce—Origin and Meaning—. In Digital Management in COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Times; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Information Cascades and Online Shopping: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study in China and the United States. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.; Gruzd, A.; Hernández-García, Á. Social Media Marketing: Who Is Watching the Watchers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.A.; Segars, A.H. An Empirical Examination of the Concern for Information Privacy Instrument. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Manickam, S.; Al-Charchafchi, A. Privacy Calculus Model for Online Social Networks: A Study of Facebook Users in a Malaysian University. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L.F.; Logan, K.; Lim, H.S. Social Media Fatigue and Privacy: An Exploration of Antecedents to Consumers’ Concerns Regarding the Security of Their Personal Information on Social Media Platforms. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, T.; Tsohou, A.; Karyda, M. Forming Digital Identities in Social Networks: The Role of Privacy Concerns and Self-Esteem. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2021, 29, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I.; Almuqrin, A.; Liu, Y.; Alhossayin, M.; Qintash, F.H. Gender Differentials on Information Sharing and Privacy Concerns on Social Networking Sites: Perspectives from Users. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; El-Gayar, O. The Effect of Privacy Policies on Information Sharing Behavior on Social Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, Hawaii, USA, 7–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahshour Rad, M.; Nilashi, M.; Mohamed Dahlan, H.; Ibrahim, O. Academic Researchers’ Behavioural Intention to Use Academic Social Networking Sites: A Case of Malaysian Research Universities. Inf. Dev. 2019, 35, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, M.A.; Blake, R.J. Analysis of Hofstedes 5-D Model: The Implications Of Conducting Business In Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. (IJMIS) 2012, 16, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Al Saifi, S.A.; Dillon, S.; McQueen, R. The Relationship between Face to Face Social Networks and Knowledge Sharing: An Exploratory Study of Manufacturing Firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannataci, J. Privacy, Technology Law and Religions across Cultures. J. Inf. Law Technol. (JILT) 2009, 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft, S.; Rekker, S. The Relationship between Culture and Information Privacy Policy. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hasan, A.; Khuntia, J.; Yim, D. Cross-Culture Online Knowledge Validation and the Exclusive Practice of Stem Cell Therapy. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 194–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, N.; Cacho-Elizondo, S.; Tossan, V. Cross-Cultural Effects in Adoption Patterns of a Mobile Coaching Service for Studies: A Comparison Between France and Mexico. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsolamy, F. Social Networking in Higher Education: Academics’ Attitudes, Uses, Motivations and Concerns; Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abokhodair, N.; Abbar, S.; Vieweg, S.; Mejova, Y. Privacy and Twitter in Qatar: Traditional Values in the Digital World. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science, Hannover, Germany, 22–25 May 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I.; Lee, J.; Almuqrin, A.; Halboob, W.; Omar, T.; Floos, A. User Concerns Regarding Information Sharing on Social Networking Sites: The User’s Perspective in the Context of National Culture. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Drake, J.R.; Hall, D. When Job Candidates Experience Social Media Privacy Violations. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Trepte, S.; Scharkow, M.; Dienlin, T. The Privacy Calculus Contextualized: The Influence of Affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyke, C.; Shim, J.T.; Johnson, R.; Jiang, J. Concern for Information Privacy and Online Consumer Purchasing. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2006, 7, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Dinev, T.; Xu, H. Information Privacy Research: An Interdisciplinary Review. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, H.; He, W.; Wang, F.-K.; Jiao, S. A Meta-Analysis to Explore Privacy Cognition and Information Disclosure of Internet Users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaburi, E.W.; Treku, D.N. Effect of Penitence on Social Media Trust and Privacy Concerns: The Case of Facebook. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Erickson, R.J.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Krantz, D. When Does Feeling in Control Benefit Well-Being? The Boundary Conditions of Identity Commitment and Self-Esteem. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronas, A.-M.K.; Louis, M.R. Restoring a Sense of Control during Implementation: How User Involvement Leads to System Acceptance. MIS Q. 1988, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, B. Developing a Questionnaire; Continuum: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.M.; Brauer, A.; Abrami, P.C.; Surkes, M. The Development of a Questionnaire for Predicting Online Learning Achievement. Distance Educ. 2004, 25, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouibah, K.; Al-Qirim, N.; Hwang, Y.; Pouri, S.G. The Determinants of EWoM in Social Commerce: The Role of Perceived Value, Perceived Enjoyment, Trust, Risks, and Satisfaction. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.; Gefen, D. Validation Guidelines for IS Positivist Research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC): The Construct, the Scale, and a Causal Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berings, D.; Adriaenssens, S. The Role of Business Ethics, Personality, Work Values and Gender in Vocational Interests from Adolescents. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmering, M.J.; Fuller, C.M.; Richardson, H.A.; Ocal, Y.; Atinc, G.M. Marker Variable Choice, Reporting, and Interpretation in the Detection of Common Method Variance. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, S. The Ethics of Online Retailing: A Scale Development and Validation from the Consumers’ Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Lee, M.; Huang, Q. Information Privacy Concern and Deception in Online Retailing. Internet Res. 2019, 30, 511–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakesley, I.R.; Yallop, A.C. What Do You Know about Me? Digital Privacy and Online Data Sharing in the UK Insurance Sector. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2019, 18, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Hu, H.-H.; Wang, L.; Qin, J.-Q. Privacy Assurances and Social Sharing in Social Commerce: The Mediating Role of Threat-Coping Appraisals. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, R.; Chen, R.; Kim, D.J.; Chen, K. Effectiveness of Privacy Assurance Mechanisms in Users’ Privacy Protection on Social Networking Sites from the Perspective of Protection Motivation Theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 135, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, J.A.; Waldman, A.E. Past the Privacy Paradox: The Importance of Privacy Changes as a Function of Control and Complexity. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2020, 5, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balapour, A.; Nikkhah, H.R.; Sabherwal, R. Mobile Application Security: Role of Perceived Privacy as the Predictor of Security Perceptions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Regulation (EU) 2016/679. Off. J. Eur. Parliam. 2016, 119, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, S.; Johnson, E.J.; Kobrin, S.J.; Lohse, G.L. International Differences in Information Privacy Concerns: A Global Survey of Consumers. Inf. Soc. 2004, 20, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, H.D.; Wilson, R.S. A Yardstick for Danger: Developing a Flexible and Sensitive Measure of Risk Perception. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evensen, D.T.; Decker, D.J.; Stedman, R.C. Shifting Reactions to Risks: A Case Study. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).