How Generation X and Millennials Perceive Influencers’ Recommendations: Perceived Trustworthiness, Product Involvement, and Perceived Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

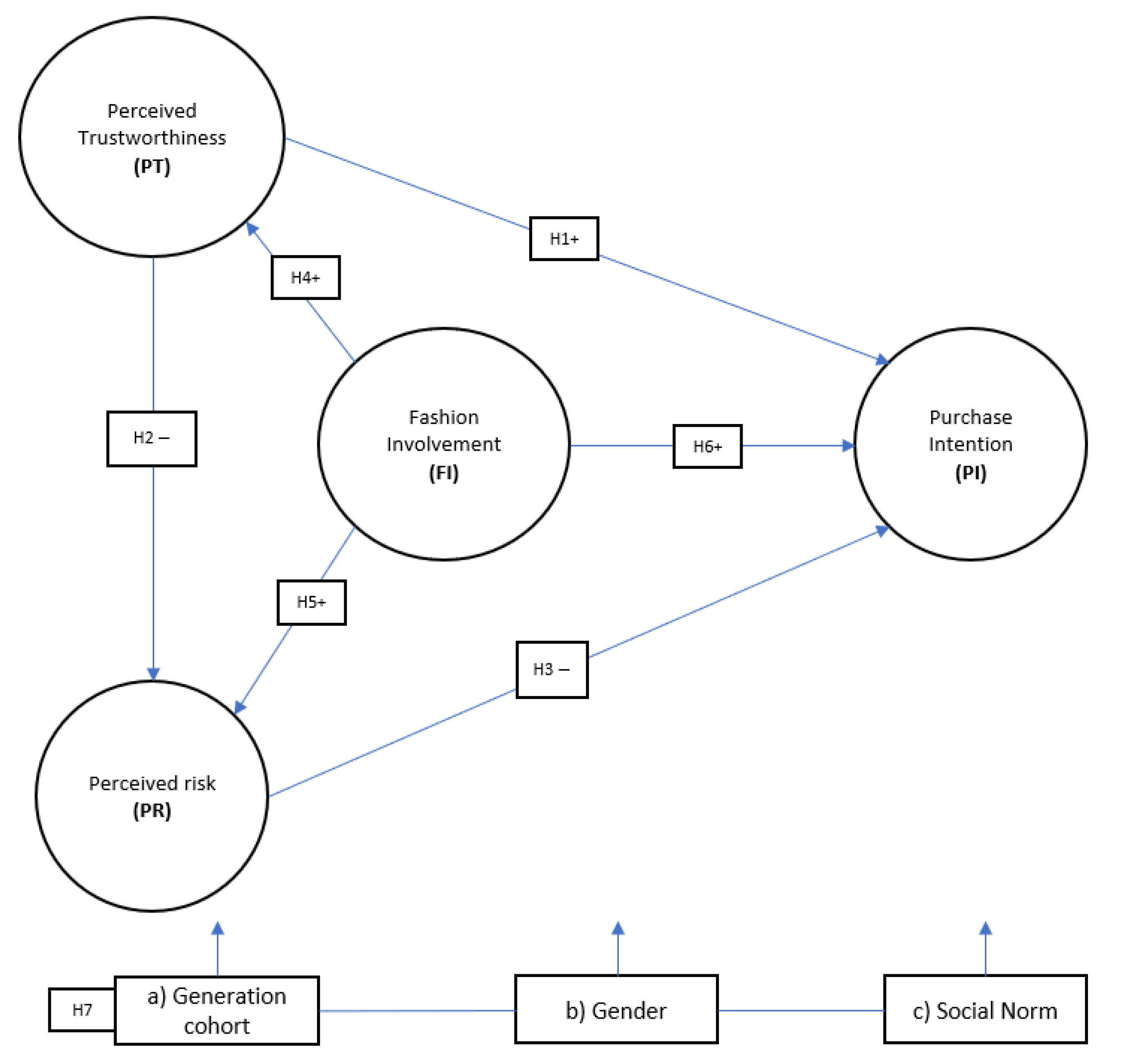

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Relationship between Perceived Trustworthiness of the Message Transmitted and Purchase Intention

2.2. Relationship between the Trustworthiness of the Message and Perceived Risk in the Recommendations

2.3. Perceived Risk in Recommendations as a Mitigating Factor in Purchase Intention

2.4. Relationships between Fashion Involvement, Perceived Trustworthiness of the Message, Perceived Risk, and Purchase Intention

2.5. Moderating Variables: Generational Cohort, Social Norm, and Gender

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Design

3.2. Measurement Instrument and Scales

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. PLS-MGA Multigroup Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista Global Digital Population as of April 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/249562/number-of-worldwide-internet-users-by-region/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bhandari, A.; Bimo, S. Why’s Everyone on TikTok Now? The Algorithmized Self and the Future of Self-Making on Social Media. Soc. Media + Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221086241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Fuentes-García, F.J.; Muñoz-Fernandez, G.A. Exploring the Emerging Domain of Research on Video Game Live Streaming in Web of Science: State of the Art, Changes and Trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetioui, Y.; Benlafqih, H.; Lebdaoui, H. How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Makrides, A.; Christofi, M.; Thrassou, A. Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freberg, K.; Graham, K.; McGaughey, K.; Freberg, L.A. Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Palmatier, R.W. Influencer Marketing Effectiveness. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 00222429221102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquila-Natale, E.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Del-Río-Carazo, L.; Cuenca-Enrique, C. Do or Die? The Effects of COVID-19 on Channel Integration and Digital Transformation of Large Clothing and Apparel Retailers in Spain. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, G.; Nan, G.; Wang, R.; Tayi, G.K. Retail Strategies for E-tailers in Live Streaming Commerce: When Does an Influencer Marketing Channel Work? SSRN 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; De Jans, S.; De Veirman, M. The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 40, 327–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Bus. Horizons 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.; Avhad, V.; Jaju, S. Influencer Marketing: An Exploratory Study to Identify Antecedents of Consumer Be-havior of Millennial. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2020, 9, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Hudders, L.; Nelson, M.R. What Is Influencer Marketing and How Does It Target Children? A Review and Direction for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchers, N.S. Social Media Influencers in Strategic Communication. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2019, 13, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Sama, R. The Effect of Influencer Marketing on Consumers’ Brand Admiration and Online Purchase Intentions: An Emerging Market Perspective. J. Internet Commer. 2019, 19, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Tipi, N. Generation X versus millennials communication behaviour on social media when pur-chasing food versus tourist services. E+M Ekon. A Manag. 2018, 21, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Equihua, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Romero, J. How old is your soul? Differences in the impact of eWOM on Generation X and millennials. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 5, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosdahl, D.J.; Carpenter, J.M. Shopping orientations of US males: A generational cohort comparison. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshbhag, R.R.; Mohan, B.C. Study on influential role of celebrity credibility on consumer risk perceptions. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2020, 12, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msallati, A. Investigating the nexus between the types of advertising messages and customer engagement: Do customer in-volvement and generations matter? J. Innov. Digit. Mark. 2021, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavadi, C.A.; Sirothiya, M.; Vishwanatha, M.R.; Yatgiri, P.V. Analysing the Moderating Effects of Product Involvement and Endorsement Type on Consumer Buying Behaviour: An Empirical Study on Youth Perspective. IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.J. Application of the value-belief-norm model to environmentally friendly drone food delivery services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Santos-Roldán, L.M.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk in influencers’ product recommendations on their followers’ purchase attitudes and intention. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 184, 121997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, W.; Howe, N. The Fourth Turning: What the Cycles of History Tell Us about America’s Next Rendezvous with Destiny; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, J.D. Evaluating the Credibility of Online Information: A Test of Source and Advertising Influence. Mass Commun. Soc. 2003, 6, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E. Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.F.; Rich, S.U. Perceived Risk and Consumer Decision-Making—The Case of Telephone Shopping. J. Mark. Res. 1964, 1, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Datareportal Digital 2022: Sapin. 2022. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E.; Muqaddam, A. I trust what she’s #endorsing on Instagram: Moderating effects of parasocial interaction and social presence in fashion influencer marketing. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Okros, A. Generational Theory and Cohort Analysis. In Harnessing the Potential of Digital Post-Millennials in the Future Work-Place; Okros, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Vitezić, V.; Perić, M. Artificial intelligence acceptance in services: Connecting with Generation Z. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S.; Kol, O. Four generational cohorts and hedonic m-shopping: Association between personality traits and purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 21, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jurado, A.; Castro-González, P.; Torres-Jiménez, M.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Evaluating the role of gamification and flow in e-consumers: Millennials versus generation X. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 1278–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.W.; Muthaly, S.; Kuppusamy, M.; Han, C. The study of online reviews and its relationship to online purchase intention for electronic products among the millennials in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1519–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Cao, D.; Lee, R. Who are social media influencers for luxury fashion consumption of the Chinese Gen Z? Categorisation and empirical examination. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.-A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Dabija, D.-C.; Alt, M.-A. The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, K.; Islam, T. Digital influencer marketing: How message credibility and media credibility affect trust and impulsive buying. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2022, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, A.; Leckie, C.; Webster, C. Cognitive and Affective Trust between Australian Exporters and Their Overseas Buyers. Australas. Mark. J. 2012, 20, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golembiewski, R.T.; McConkie, M. The centrality of interpersonal trust in group processes. Theor. Group Process. 1975, 131, 131–185. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpandé, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relationships. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2018, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial inter-action influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwidienawati, D.; Tjahjana, D.; Abdinagoro, S.B.; Gandasari, D.; Munawaroh. Customer review or influencer endorsement: Which one influences purchase intention more? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Willemsen, L.M.; Van Der Aa, E.P. “This Post is Sponsored” Effects of Sponsorship Disclosure on Persuasion Knowledge and Electronic Word of Mouth in the Context of Facebook. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Khwaja, M.G.; Mahmood, A.; Turi, J.A.; Latif, K.F. Refining e-shoppers’ perceived risks: Development and valida-tion of new measurement scale. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V. Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualisations and models. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, R.H.; Dantas, D.C.; Sénécal, S. Watch Your Tone: How a Brand’s Tone of Voice on Social Media Influences Consumer Responses. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 41, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, S.L.; Eckert, S. #sponsored: Consumer insights on social media influencer marketing. Public Relations Inq. 2020, 9, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Esteban-Millat, I.; Torrez-Meruvia, H.; D’Alessandro, S.; Miles, M. Influencer marketing: Brand control, commercial orientation and post credibility. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 1805–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Larsen, S.; Øgaard, T. How to define and measure risk perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Biswas, A.; Das, N. The Differential Effects of Celebrity and Expert Endorsements on Consumer Risk Perceptions. The Role of Consumer Knowledge, Perceived Congruency, and Product Technology Orientation. J. Advert. 2006, 35, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmadi, P.; Rahimian, M.; Movahed, R.G. Theory of planned behavior to predict consumer behavior in using products irrigated with purified wastewater in Iran consumer. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, A.E.; Mazzocchi, M.; Traill, W.B. Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Ansari, N.Y.; Razzaq, Z.; Awan, H.M. The Impact of Fashion Involvement and Pro-Environmental Attitude on Sustainable Clothing Consumption: The Moderating Role of Islamic Religiosity. SAGE Open 2018, 8, 2158244018774611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Commuri, S.; Arnold, T.J. Exploring the origins of enduring product involvement. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2009, 12, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I. Beyond the fad: A critical review of consumer fashion involvement. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 37, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A. Fashion clothing consumption: Antecedents and consequences of fashion clothing involvement. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, G.; Grimmer, M.; Grimmer, L.; Wang, S.; Su, J. A cross cultural examination of “off-price” fashion shopping. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, Y.; Mann, B.J.S.; Ghuman, M.K. Impact of celebrity endorser as in-store stimuli on impulse buying. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2020, 30, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Saura, J.R.; Martinez-Navalon, J.G. The Impact of e-WOM on Hotels Management Reputation: Exploring TripAdvisor Review Credibility With the ELM Model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68868–68877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B. Understanding the consumer’s online merchant selection process: The roles of product involvement, perceived risk, and trust expectation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Campusano, P. Restaurants and the Bring-Your-Own-Bottle of Wine Paradox: Involvement Influences, Consumption Occasions, and Risk Perception. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2017, 21, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Cohen, J. Craft beer in the situational context of restaurants: Effects of product involvement and antecedents. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2199–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Zhu, W.; Benyoucef, M. Impact of product description and involvement on purchase intention in cross-border e-commerce. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 120, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Jaeger, S.R.; Brodie, R.J.; Balemi, A. The influence of involvement on purchase intention for new world wine. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali-Zinoubi, Z.; Toukabri, M. The antecedents of the consumer purchase intention: Sensitivity to price and involvement in organic product: Moderating role of product regional identity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Wang, G. How Social Ties Influence Customers’ Involvement and Online Purchase Intentions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 16, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R. Consumer values, fashion consciousness and behavioural intentions in the online fashion retail sector. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C.; Martínez, J.A.J.; Hoyos, M.M.-D. Tell me your age and I tell you what you trust: The moderating effect of generations. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Wang, M.; Mikulić, J.; Kunasekaran, P. A critical review of moderation analysis in tourism and hospi-tality research toward robust guidelines. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4311–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernin, A. The Effects of Food Marketing on Children’s Preferences: Testing the Moderating Roles of Age and Gender. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2008, 615, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, I.; Laroche, M.; Paulin, M. Development of market Mavenism traits: Antecedents and moderating effects of culture, gender, and personal beliefs. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 69, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Leung, X.Y.; Bai, B. How social media influencer’s event endorsement changes attitudes of followers: The moderating effect of followers’ gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2337–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, V.; Murphy, K.S.; Severt, D. Does service quality really matter at Green restaurants for Millennial consumers? The moderating effects of gender between loyalty and satisfaction. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaei, N.; Nikhashemi, S. Generation Y consumers’ buying behaviour in fashion apparel industry: A moderation analysis. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 21, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, V.; Stoel, L.; Brantley, A. Mall attributes and shopping value: Differences by gender and generational cohort. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Ryu, K.; Cobanoglu, C.; Rezaei, S.; Wulan, M.M. Examining the Effect of Shopping Mall Attributes in Predicting Tourist Shopping Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: Variation across Generation X and Y. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 22, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.S.; Seo, S.; Li, Z.; Austin, E.W. What people TikTok (Douyin) about influencer-endorsed short videos on wine? An exploration of gender and generational differences. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2022, 13, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; Sujanto, R.Y.; Sulistiawan, J.; Aw, E.C.-X. What is holding customers back? Assessing the moderating roles of personal and social norms on CSR’S routes to Airbnb repurchase intention in the COVID-19 era. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V.; Oksanen, A.; Räsänen, P.; Blank, G. Social Media, Web, and Panel Surveys: Using Non-Probability Samples in Social and Policy Research. Policy Internet 2021, 13, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.F.; Alanadoly, A.B. Personality traits and social media as drivers of word-of-mouth towards sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thesocialflame María Pombo en Instagram. Available online: https://thesocialflame.com/influencer/mariapombo (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Chaudhuri, A. A Macro Analysis of the Relationship of Product Involvement and Information Search: The Role of Risk. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2000, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnukka, J.; Uusitalo, O.; Toivonen, H. Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, B.; Woo, H. Modeling consumers’ intention to use fashion and beauty subscription-based online services (SOS). Fash. Text. 2018, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. e-Collab. (IJeC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international market-ing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A primer for soft modeling. In A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; p. xiv, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.; Götz, O.; Wetzels, M.; Wilson, B. On the Use of Formative Measurement Specifications in Structural Equation Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study to Compare Covariance-Based and Partial Least Squares Model Estimation Methodologies; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- AlFarraj, O.; Alalwan, A.A.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Baabdullah, A.; Aldmour, R.; Al-Haddad, S. Examining the impact of influencers’ credibility dimensions: Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise on the purchase intention in the aesthetic dermatology industry. Rev. Int. Bus. Strat. 2021, 31, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, E.A.; Belarmino, A. Risk mitigation through source credibility in online travel communities. Anatolia 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M. A motivational process model of product involvement and consumer risk perception. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1340–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.C.; Kim, Y. Why Consumers Hesitate to Shop Online: Perceived Risk and Product Involvement on Taobao.com. J. Promot. Manag. 2016, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.G.; Chalip, L. Effects of co-branding on consumers’ purchase intention and evaluation of apparel attributes. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2013, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V. Impact of fashion interest, materialism and internet addiction on e-compulsive buying behaviour of apparel. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B. Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on social media? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupkau, C.; Ruiz-Valenzuela, J. Work and children in Spain: Challenges and opportunities for equality between men and women. SERIEs 2021, 13, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-K.; Chang, Y.-J.; Chang, I.-C. A pro-environmental behavior model for investigating the roles of social norm, risk perception, and place attachment on adaptation strategies of climate change. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25178–25189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchers, N.S.; Enke, N. “I’ve never seen a client say: ‘Tell the influencer not to label this as sponsored’”: An exploration into influencer industry ethics. Public Relat. Rev. 2022, 48, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Han, J. Detecting Engagement Bots on Social Influencer Marketing; Aref, S., Bontcheva, K., Braghieri, M., Dignum, F., Giannotti, F., Grisolia, F., Pedreschi, D., Eds.; Social Informatics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective influencer marketing: A social identity perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Male (n = 68) | Female (n = 183) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27.0% | 72.90% | |||

| Age | 26–30 (M *) | 26 | 43 | 69 (27.5%) |

| 31–35 (M) | 10 | 23 | 33 (13.1%) | |

| 36–40 (M) | 4 | 10 | 14 (5.6%) | |

| 41–45 (X *) | 6 | 22 | 28 (11.2%) | |

| 46–50 (X) | 6 | 27 | 33 (13.1%) | |

| 51–55 (X) | 7 | 31 | 38 (15.1%) | |

| 56–60 (X) | 7 | 20 | 27 (10.8%) | |

| 60 (X) | 2 | 7 | 9 (3.6%) | |

| Education | Primary level or lower | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.8%) |

| Middle school | 3 | 19 | 22 (8.8%) | |

| High school | 23 | 49 | 72 (28.7%) | |

| University | 25 | 82 | 107 42.6%) | |

| Master | 15 | 26 | 41 (16.3%) | |

| PhD | 2 | 5 | 7 (2.8%) | |

| Employment | Entrepreneur/self-employed | 14 | 20 | 34 (13.5%) |

| Employed | 28 | 68 | 96 (38.2%) | |

| Officer | 10 | 40 | 50 (19.9%) | |

| Student | 11 | 15 | 26 (10.4%) | |

| Housework | 1 | 21 | 22 (8.8%) | |

| Retired | 2 | 5 | 7 (2.8%) | |

| Unemployed | 2 | 14 | 16 (6.4%) | |

| Available family income (EUR/month) | EUR < 1000 | 13 | 27 | 40 (15.9%) |

| EUR 1001–2000 | 23 | 71 | 94 (37.5%) | |

| EUR 2001–3000 | 15 | 42 | 57 (22.7%) | |

| EUR 3001–4000 | 8 | 24 | 32 (12.7%) | |

| EUR 4001–5000 | 5 | 9 | 14 (5.6%) | |

| EUR 5.001 | 4 | 10 | 14 (5.6%) | |

| Social Norm | High | 38 | 89 | 127 (50,6%) |

| Medium–low | 30 | 94 | 124 (49,4%) |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | Average (Sd. Dev) | Adapted from: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Risk (PR) | PR1. I think it is risky to buy products recommended by influencers | 0.933 | 4.116 (1.800) | [97,98] |

| PR2. I am concerned about the result I will get if I buy a product sponsored by an influencer | 0.868 | 3.980 (1.806) | ||

| PR3. I am concerned about the overall risk I take by buying products recommended by influencers | 0.807 | 3.773 (1.851) | ||

| Perceived Trustworthiness (PT) | PT1. I believe fashion influencers’ recommendations are honest | 0.918 | 2.669 (1.609) | [40,44,99] |

| PT2. I consider the recommendations of fashion influencers to be trustworthy | 0.942 | 2.725 (1.634) | ||

| PT3. I think fashion influencers’ recommendations are truthful | 0.944 | 2.813 (1.600) | ||

| Fashion Involvement(FI) | FI1. I usually have one or more outfits of the very newest style | 0.706 | 4.275 (2.251) | [25,64,100] |

| FI2. I keep my wardrobe up-to-date with the changing fashions | 0.825 | 3.028 (2.034) | ||

| FI3. Fashionable, attractive styling is very important to me | 0.869 | 3.131 (1.928) | ||

| FI4. I am very involved with fashion. Fashion items are part of my way of life | 0.855 | 3.104 (1.903) | ||

| Purchase Intention (PI) | PI1. I intend to buy fashion products recommended by influencers | 0.925 | 2.104 (1.566) | [4,60] |

| PI2. In the future, I will try to buy products sponsored by influencers | 0.948 | 2.016 (1.453) | ||

| PI3. I will effort to buy fashion products recommended by influencers | 0.906 | 1.78 (1.432) |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE | PR | PT | FI | PI | |

| Perceived Risk (PR) | 0.855 | 1.088 | 0.904 | 0.759 | 0.871 | |||

| Perceived Trustworthiness (PT) | 0.928 | 0.929 | 0.954 | 0.874 | −0.177 | 0.935 | ||

| Fashion Involvement (FI) | 0.832 | 0.848 | 0.888 | 0.666 | −0.057 | 0.495 | 0.816 | |

| Purchase Intention (PI) | 0.918 | 0.929 | 0.948 | 0.858 | −0.239 | 0.543 | 0.360 | 0.926 |

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Path Coefficient (p-Value) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PT |  | PI | 0.453 (0.000) *** | Supported |

| H2 | PT |  | PR | −0.197 (0.005) ** | Supported |

| H3 | RP |  | PI | −0.152 (0.003) ** | Supported |

| H4 | FI |  | PT | 0.495 (0.000) *** | Supported |

| H5 | FI |  | PR | 0.041 (0.305) | Not supported |

| H6 | FI |  | PI | 0.127 (0.015) ** | Supported |

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|

| PI | 0.328 | 0.320 |

| PT | 0.246 | 0.242 |

| PR | 0.032 | 0.025 |

| Variable | Path Coefficients | Path Coefficient Difference | Henseler’s MGA | Welch–Satterthwaite Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Millennials | Gen X | β1-β2 | p-valor | Student’s t-test | p-valor |

| PT-PI | 0.365 *** | 0.541 *** | −0.176 | 0.070 * | 1.470 | 0.072 * |

| RP-PI | −0.238 ** | −0.076 | −0.162 | 0.078 * | 1.369 | 0.087 * |

| Social Norm | High | Medium–Low | β1-β2 | p-valor | Student’s t-test | p-valor |

| PT-RP | −0.392 *** | −0.060 | −0.332 | 0.034 ** | 1.934 | 0.055 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Fuentes-García, F.J.; Cano-Vicente, M.C.; González-Mohino, M. How Generation X and Millennials Perceive Influencers’ Recommendations: Perceived Trustworthiness, Product Involvement, and Perceived Risk. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1431-1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040072

Cabeza-Ramírez LJ, Fuentes-García FJ, Cano-Vicente MC, González-Mohino M. How Generation X and Millennials Perceive Influencers’ Recommendations: Perceived Trustworthiness, Product Involvement, and Perceived Risk. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2022; 17(4):1431-1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabeza-Ramírez, L. Javier, Fernando J. Fuentes-García, M. Carmen Cano-Vicente, and Miguel González-Mohino. 2022. "How Generation X and Millennials Perceive Influencers’ Recommendations: Perceived Trustworthiness, Product Involvement, and Perceived Risk" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17, no. 4: 1431-1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040072

APA StyleCabeza-Ramírez, L. J., Fuentes-García, F. J., Cano-Vicente, M. C., & González-Mohino, M. (2022). How Generation X and Millennials Perceive Influencers’ Recommendations: Perceived Trustworthiness, Product Involvement, and Perceived Risk. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(4), 1431-1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040072