Abstract

Considering consumer fairness concerns, this paper investigates an e-commerce platform’s selling scheme choice when it adopts a wholesale selling scheme or an agency selling scheme to create a contract with a manufacturer. We find that the intensity of the fairness concerns and the platform fee are key factors affecting the platform’s optimal selling scheme choice. Specifically, when these two factors are relatively high or low, the wholesale selling scheme outperforms the agency selling scheme in terms of the e-commerce platform’s profit. Otherwise, the e-commerce platform should adopt the agency selling scheme. Moreover, when these two factors are sufficiently large or small, the wholesale selling scheme will yield a win-win result for the players of the e-commerce supply chain. Interestingly, we find that, considering fairness-minded consumers, a larger platform fee may be harmful to the platform. We also extend the baseline model to consider the consumer heterogeneity of fairness concerns, proportional platform fee, fairness concern about the manufacturer’s profit, and endogenous platform fee. We find that the main insights remain qualitatively unchanged under these model extensions.

1. Introduction

With the rise of the platform economy, e-commerce platform selling has witnessed strong growth in recent decades [1]. Global e-commerce sales reached $3.53 trillion in 2019, and electronic retailing revenue is expected to grow to $6.54 trillion by 2022. Traditionally, the platform has acted as a reseller in which the e-commerce platform owner purchases products from a manufacturer and then sells them to consumers [2]. However, the rapid growth of online retailing has urged platforms to serve as a marketplace, allowing manufacturers to directly sell products to consumers and charging a platform fee for each sale [3,4]. In this paper, the former mode is called the “wholesale selling scheme”, whereas the latter mode is referred to as the “agency selling scheme”. Some giant platforms in the online retail industry, such as Taobao.com in China, Sears in the US, and Flipkart in India, have embraced the agency selling scheme [5]. The agency selling scheme has also become prevalent in other industries, such as the e-book industry [6,7] and the app market [8]. However, some major e-commerce platforms, e.g., BestBuy.com and Zappos.com, still use the wholesale selling scheme. The wholesale selling scheme continues to prevail as the dominant selling strategy in some industries, such as the music industry and apparel industry [9]. Some recent literature about the e-commerce platform’s choice of selling scheme includes Wei et al. [10], Liu and Ke [11,12], Chen et al. [13], and Chen et al. [14]. The above papers have discussed the impact of different factors, such as product complementarity, promotion, cross-channel spillover, and consumer loyalty, on the e-commerce platform’s selling scheme choice from the pure wholesale selling scheme and pure agency selling scheme. However, the above papers tend to assume that firms or consumers are perfectly rational, but, in fact, they are bounded rational.

As a type of bounded rationality, fairness concern acts as a key role in the decision-making behavior of manufacturers, retailers, and consumers [15]. In this paper, we specifically focus on discussing the fairness concern from the perspective of the consumer. There are two kinds of consumer fairness concerns in the literature: one is taking the retail prices of peers as a reference point [16,17], and the other is treating the profit obtained by a participant of the supply chain as a reference point [18,19]. In this paper, we mainly investigate the latter kinds of consumer fairness concerns. We refer the reader to two seminal papers [15,20] in behavioral economics that examine the impact of consumer fairness concern on the firm strategy through theoretical models.

With the rapid development of the Internet, consumer fairness concerns toward transactions are growing due to increasing news reports about the trade inequality in different industries. For example, in the gasoline market, more and more news reports cover industry-collusion-increased gasoline prices, and gasoline companies make a large amount of profits [17]. In the budget hotel industry, consumers who seek fairness in transactions will punish a hotel if the price is high. Under such a market, if consumers feel that the price of a hotel is unfair, they can easily turn to other hotels [18]. In the catering industry, restaurants cheated the consumers by selling wine at too high prices [19]. In the pharmaceutical industry, pharmaceutical firms reap huge profits from drugs [21]. Consumers perceived that the retail prices of drugs are too high and pharmaceutical prices should be regulated. The above industry practices show that fairness-minded consumers are willing to sacrifice their monetary returns and sometimes even abandon deals to punish greedy sellers.

There is also anecdotal evidence that consumers may be concerned about the fairness of transactions. For example, Campbell [22] found that consumers’ conjecture about corporate profits will affect their perceptions of price fairness. According to a survey of 4058 Americans conducted by BusinessWeek, approximately 73% of consumers deem the trading prices of products of giant American firms to be unfair and unreasonable, and the consumers will choose to give up buying products if they think that the price is unfair [23]. More recently, Guo and Jiang [18] conducted a survey of 170 students and showed that over 50% of students will not purchase products, even if the purchasing behavior might bring a return of $5, when the students realized that the company’s marginal profit was $18 or more. In the fields of economics and marketing, there is much literature on investigating consumer concerns about fairness, e.g., Guo [17], Kahneman et al. [24], and Xia et al. [25]. Moreover, existing literature has shown that the consumers tend to think that the price of a firm is unfair when the profit of the firm is higher than the surplus of the consumer [15,26].

With the development of the Internet and the continuous updating of information technologies (such as blockchain and big data), consumers can better understand the information related to products through various channels. Then, products’ information, such as retail price and production cost, have become more transparent to consumers [27,28]. For example, Techinsights, a foreign business data analysis firm, recently disassembled Apple’s iPhone Pro MAX and analyzed its cost structure. The transparency of price and cost information enables fairness-minded consumers to clearly measure the gap between their own consumer surplus and the seller’s profit margin in the process of product purchase. When consumers think that merchants grab too high profits from product sales, consumers will feel that the transaction is unfair, and their willingness to pay will be reduced. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the impact of consumer fairness concern on the members of the supply chain.

The above industry practices, anecdotal evidence, and existing literature all indicate that, when the profit of a firm is higher than the surplus of consumers, consumers tend to think that the firm’s price is unfair. Therefore, the total utility that consumers obtain from products relies on both the monetary return of the consumer and the profitability of the firm [18]. Previous literature in behavioral economics has indicated that consumer fairness concerns act as a critical role in the strategies of consumers and firms [15,18,20,26]. The research focus on the existing literature is how to set a “fair” price for consumers and firms. However, the fairness concerns of consumers hold great consequences. For example, fairness-minded consumers are willing to sacrifice their monetary returns and sometimes even abandon deals to punish greedy sellers. In fact, approximately 85% of people are inclined to punish unfair transactions, even if that behavior is costly and not immediately rewarded [29]. Therefore, the consumer fairness concern has a huge impact on the operation of firms, which will not only affect the firms’ profitability but also affect the strategic choice of firms, such as the selling scheme choices for e-commerce platforms.

Motivated by the above discussions, this paper is interested in the following research questions:

- (1)

- In the presence of consumer fairness concerns, what is the strategic selling scheme for an e-commerce platform?

- (2)

- Is the e-commerce platform more inclined to adopt a novel platform pricing scheme rather than a traditional wholesale pricing scheme, and, if so, under what conditions?

- (3)

- Which pricing scheme would be preferred by the upstream manufacturer?

- (4)

- How does the interaction between fairness concerns and an e-commerce platform’s selling scheme choice affect consumer surplus and social welfare?

To theoretically answer the above research questions, we adopted the rational expectations hypothesis, where economic outcomes are self-fulfilled and in line with people’s expectations [30,31,32,33]. In our research setting, on the one hand, given the expectation of the wholesale price and retail price, fair-minded consumers make purchase or non-purchase decisions. On the other hand, given the expectation of consumers’ willingness to pay, the manufacturer or platform determines the pricing decision. Furthermore, the expectation of every player in the supply chain system (i.e., manufacturer, platform, and consumers) is in line with actual outcomes. The rational expectations hypothesis is widely used in several domains, such as two-sided market [34], finance [35], online platforms [36], etc.

Based on the rational expectations hypothesis, we examined the desirability of an e-commerce platform’s selling scheme choice in the presence of consumers’ fairness concern behavior. The purpose of this paper is to investigate an e-commerce platform’s selling scheme choice when it adopts a wholesale selling scheme or an agency selling scheme to make a contract with a manufacturer in the presence of consumer fairness concerns. In particular, we established a supply chain game consisting of a single upstream manufacturer and a single downstream platform with a continuum of consumers with fairness concerns. The downstream platform can use the traditional wholesale selling scheme or adopt the novel agency selling scheme. We first obtained equilibrium results under the two selling schemes, and then compared the two schemes from the perspectives of the platform’s profit, the manufacturer’s profit, consumer surplus, and social welfare. For parsimony and analytical tractability, our baseline model characterized consumers as homogenous about fairness concerns. We also extended the baseline model to consider heterogeneous consumers in terms of fairness concerns, proportional platform fee, fairness concerns about the manufacturer’s profit, and endogenous platform fee.

Our research provides several managerial findings. First, the intensity of fairness concern and the platform fee are two key factors affecting the optimal selling scheme choice of the upstream platform. More specifically, our results reveal that, when these two factors are relatively high or low, the traditional wholesale selling scheme outperforms the new agency selling scheme in terms of the e-commerce platform’s profit. Otherwise, the e-commerce platform should adopt the agency selling scheme. Intuitively, when the fairness concern intensity is relatively low, a low platform fee implies that the platform can only retain a small part of the revenue, which is not conducive to the platform’s adoption of the agency selling scheme. However, when the fairness concern intensity is relatively high, as a rational economist, the platform will transfer the control rights for product pricing to the manufacturer to avoid suffering more loss. Consequently, the platform will use the wholesale selling scheme in this case. The above results are consistent with the industry practice wherein both selling schemes coexist. In the luxury industry, many brands, such as Hermes, Armani, and Louis Vuitton, have adopted the agency selling scheme to distribute their products. This is because consumers who buy luxury goods usually care little about fairness: they are fairness-neutral. However, in the budget hotel industry, platforms usually use the wholesale selling scheme. This is because consumers who use budget hotels usually care more about fairness: they are fairness-minded. If consumers feel that the price of a hotel is unfair, they can easily turn to other hotels.

Second, we find that, when the fairness concern intensity is relatively high and the platform fee is relatively low or vice versa, both members of the supply chain system will benefit from the agency selling scheme. The intuition of the win-win result relies on the trade-off between the double marginalization effect and the fairness concern effect. If the fairness concern intensity and the platform fee are either high or low enough, then the fairness concern effect will dominate the double marginalization effect, making both members better off. Otherwise, the double marginalization effect dominates the fairness concern effect, and both members are worse off. Furthermore, we obtain a win-win-win result where the upstream manufacturer, the downstream platform, and end consumers all benefit from the novel agency selling scheme when the platform fee is relatively low.

Third, we find that the e-commerce platform’s profit first increases and then decreases with the platform fee. Moreover, there exists a threshold for the platform fee, below which, adopting the wholesale selling scheme will reduce the market share for the e-commerce platform and, above which, adopting the wholesale selling scheme will increase the platform’s market share. If the platform fee is relatively low, i.e., using the agency selling scheme to sell the product is not expensive for the manufacturer, then the double marginalization effect derived from the decentralized channel structure will dominate the fairness concern effect derived from consumers’ utility inequity. However, if the platform fee is relatively high, i.e., the agency selling scheme is very costly, then the fairness concern effect dominates the double marginalization effect.

To reflect the fact that some consumers are fairness-minded whereas others are fairness-neutral, we extended the core model to capture consumer heterogeneity of the fairness concerns. Our analysis reveals that the main insights derived from the baseline model remain robust. We also obtain several new insights into the extension of considering consumer heterogeneity. Interestingly, the profit of the manufacturer has nothing to do with the fraction of the fairness-minded segment under the wholesale selling scheme, whereas the manufacturer’s profit first increases and then decreases with the fraction of the fairness-minded segment under the agency selling scheme. The intuition behind this insight is as follows. On the one hand, intuitively, a larger fraction of the fairness-minded segment induces the platform to set a lower platform fee, which, in turn, indicates that the transaction is fair, and then more consumers buy the product. The lower platform fee and higher market share give the manufacturer more profits. On the other hand, when the proportion of fairness-minded consumers is small, the platform has no incentive to reduce the platform fee. In this case, consumers feel that the transaction is unfair, and then more transactions are interrupted, which, in turn, hurts the manufacturer. In addition, we also extended our baseline model to investigate the exogenous proportion platform fee, fairness concern about the manufacturer’s profit, and endogenous platform fee. The theoretical analysis reveals that the main conclusions presented in the baseline model remain qualitatively unchanged.

Compared with extant studies, our research contributes to the following two aspects. On the one hand, we contribute to the research stream of fairness concerns in distribution channel management by discussing the impact of the consumer fairness concern on the whole supply chain system and finding that the wholesale selling scheme can derive a win-win outcome for the platform and the manufacturer when the intensity of the fairness concerns and the platform fee is sufficiently large or small. On the other hand, this paper contributes to the literature on selling scheme choice in platform retailing by considering the consumer fairness concern. In the presence of fairness concerns, we illustrate a win-win-win result where the upstream manufacturer, the downstream platform, and end consumers all benefit from the novel agency selling scheme.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature. In Section 3, we set up the main model. Section 4 presents the equilibrium analysis of the game-theoretical models. In Section 5, we compare the two models and derive some managerial insights. Section 6 presents four extensions of the baseline model. In Section 7, we compare the results obtained with similar previous research and with our paper’s opinion on the differences. We provide several managerial implications and outline future research directions in Section 8. All proofs of lemmas, corollaries, and propositions are provided in Appendix A.

2. Literature Review

This paper involves two research streams, namely, fairness concerns in distribution channel management and selling scheme choice in platform retailing. In this section, we present previous studies relevant to each stream and highlight the core differences between our paper and each research stream.

2.1. Fairness Concerns in Distribution Channel Management

Consumers may take different reference points as fair in different settings, such as based on peer-comparison (e.g., consumers may feel unfair if the firm offers a lower price to the others) [15,37], distribution of the economic surplus between consumers and firms (e.g., consumers may feel unfair if they obtain a very small fraction of the total surplus) [17,18], and the relative price or markup among competitors’ products [16,38].

Fehr and Schmidt [15] put forward a peer-induced inequity aversion model to catch the concept that consumers experience negative utility due to different returns from others. Li and Jain [16] considered the influence of peer-induced fairness on pricing strategies based on firm behavior. They found that consumers’ fairness concerns can improve the social welfare of market participants. Guo [17] found that the buyer’s surplus may be non-monotonically affected by the increase in the degree of fairness concern. Guo and Jiang [18] concluded that there is a nonmonotonic relationship between the optimal quality of products and consumer fairness concerns. Yi et al. [19] investigated the influence of consumer concerns about fairness on manufacturers’ choice of distribution channel. Bolton et al. [21] pointed out that consumers’ fairness perception is affected by the consumers’ belief in the production or sales cost of a firm. Cui et al. [37], who conducted a pioneering study about the application of distributional-induced fairness in distribution channel management, investigated how the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s fairness concerns affect the coordination problem of a dyadic supply channel. Harutyunyan et al. [39] studied a competitive market, where consumers’ fairness is relative to the price of the firm’s competitor. Yu et al. [40] found that consumer fairness concern behavior hurts the retailer’s profit. Huang et al. [41] pointed out that consumers’ concern about fairness has a negative influence on retail price. Similarly, Diao et al. [42] found that consumer concerns about fairness lead to lower retail prices for a product in both periods.

Compared with the previous literature, this paper has the following differences. First, the existing papers do not address the influence of fairness concerns on the whole supply chain system. Our paper fills this important gap and obtains a win-win outcome for the platform and the manufacturer. Second, the implications of the platform’s selling scheme on consumer surplus and social welfare are also discussed. Finally, we extended our baseline model to the case where consumers are heterogeneous in fairness concerns, i.e., some consumers are transaction fairness-minded whereas others are transaction fairness-neutral. After theoretical analysis and numerical simulation, we find that the main results of the baseline model are qualitatively valid. We also derive a new conclusion: the manufacturer’s profit is an inverted-U-shape curve concerning the fraction of the fairness-minded segment.

2.2. Selling Scheme Choice in Platform Retailing

This paper is also related to an emerging body of research on selling scheme choice in platform retailing. In the initial paper on agency pricing, Hao and Fan [43] discussed wholesale selling and agency selling by considering both e-readers and e-books simultaneously. For information goods, Tan et al. [6] concluded that the agency selling scheme will benefit both the manufacturer and the platform through a revenue-sharing contract. Abhishek et al. [9] proposed that, when the agency model is not conducive to the manufacturers’ traditional physical retail, the platform prefers the agency model.

Under a vertically differentiated product setting, Tan and Carrillo [44] determined that the revenue sharing structure and the price control of upstream publishers are conducive to the benefits of the agency pricing model. Geng et al. [45] discussed the interaction between the add-on strategy of an upstream manufacturer and the distribution contract selection of a downstream platform. Yan et al. [46] investigated the agency selling scheme’s introduction in the presence of the spillover effect. Ke et al. [47] established the optimal decision analysis model to discuss the optimal decision of publishers and bookstores in the electronic book supply chain by combining the pricing models (agency model or wholesale model) and the distribution strategies (simultaneous distribution strategy or delayed distribution strategy). Chen et al. [48] discussed the influence of selling formats on the adoption of personalized pricing by considering a two-segment consumer market. The existing literature in this category points out that the agency selling scheme always makes the platform better off compared with the wholesale selling scheme. However, our results show that the agency selling scheme does not always dominate the wholesale selling scheme when considering consumers’ fairness concern behavior. Moreover, we show a counterintuitive result where a larger platform fee is inefficient for the downstream platform but beneficial to the upstream manufacturer and the whole supply chain.

Regarding the emerging stream of research on selling scheme choice in platform retailing, our paper is closely related to Zhang et al. [5]. Zhang et al. [5] discussed the interaction between the contract choice of a downstream platform and the product quality decision of an upstream manufacturer. Different from Zhang et al. [5], we conducted a comparative study on the wholesale selling and agency selling schemes in the presence of fairness concerns. We show that the wholesale selling scheme will derive a win-win-win outcome when the fairness concern intensity and the platform fee are sufficiently large or small.

3. Model

Consider a supply chain system composed of an upstream manufacturer that provides products, a downstream platform that intermediates sales, and a continuum of consumers with fairness concerns. Throughout this paper, the subscript denotes the platform’s selling scheme. In particular, we use subscripts “” and “” to represent the cases of the wholesale selling scheme and the agency selling scheme. Following the literature [49,50,51,52], a consumer purchases at most one unit of product and makes the purchase decision based on utility maximization.

It is assumed that the market information is transparent. This assumption is based on the following considerations. First, some firms voluntarily disclose their costs to consumers; examples are abundant, such as Everlane, a San Francisco-based online retailer, and Honest, a Belgian retailer (Liu et al. [53]). Second, the ubiquity of the modern Internet has given consumers a huge amount of information about products, which makes the cost of products transparent to potential consumers. Such a kind of assumption is widely used in Yi et al. [19], Huang et al. [41], and Liu et al. [53]. Consumers have information about the price and cost of products, which is provided by the external market and is not directly influenced by firms. The decisions of manufacturers, e-commerce platforms, and consumers all satisfy the rational expectation equilibrium [30,31]. The notations used in this paper are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Notations.

3.1. Supply Chain Structure

Following Abhishek et al. [9], Geng et al. [45], and Kwark et al. [49], the decision-maker in the selling scheme is the platform. This model setup is consistent with many business practices. For example, the e-book retailer Apple often possesses significantly more market power than its fellow publishers in determining which selling scheme should be used. Such a platform-leading supply chain game is also observed in various business industries, such as the online travel industry [54], the hotel industry [55], etc. The platform’s leadership in choosing the selling scheme is also because the selling scheme choice is particularly important for a powerful platform. Moreover, the platform can even set participation rules for the manufacturer [5]. The above model setup is also widely used in the operation management literature (e.g., [44,45]) and the information management literature (e.g., [43,49]). At the beginning of a selling season, the platform decides which selling scheme (wholesale or agency) to choose from, aiming to obtain more profit.

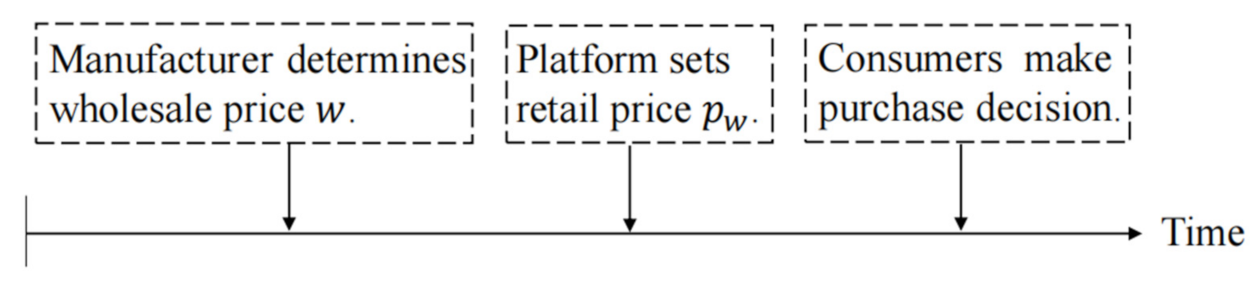

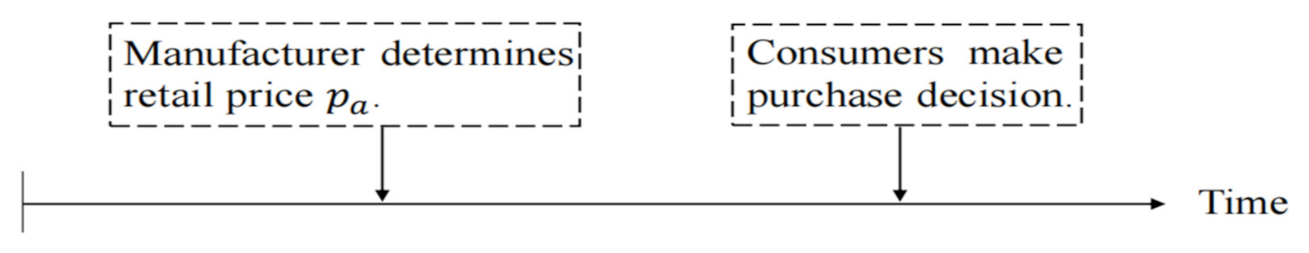

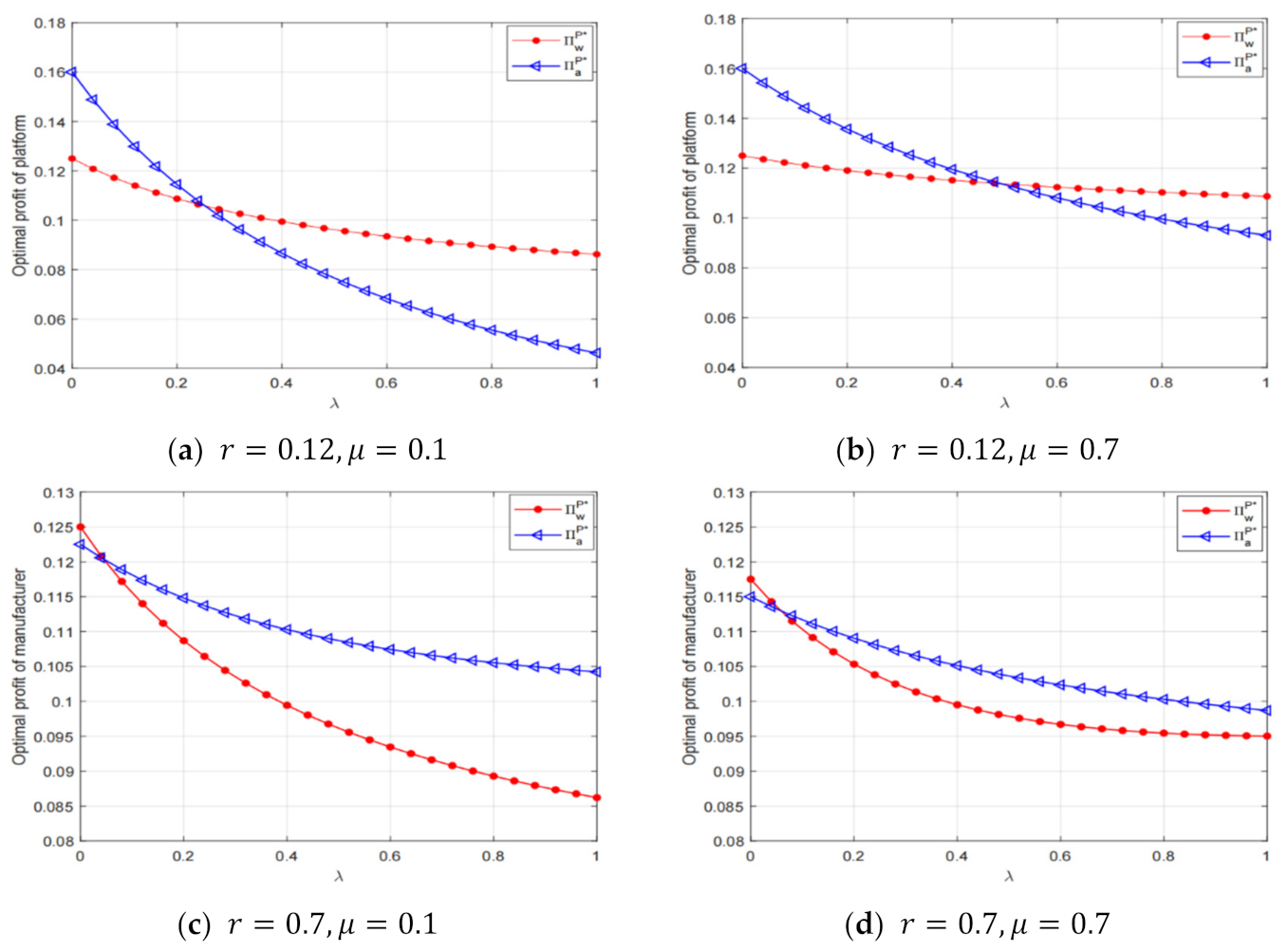

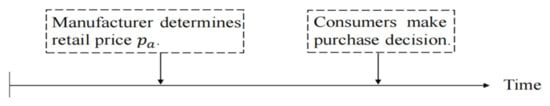

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the platform resells the products bought from the manufacturer to consumers. The sequence of events under the wholesale selling scheme is illustrated in Figure 1 and described as follows: the manufacturer first determines the product’s wholesale price , the platform then lays down the product’s retail price , and, finally, consumers make their purchasing decisions. Under the agency selling scheme, an upstream manufacturer can sell the product to consumers through the platform. This selling scheme is widely used in the digital publishing industry [43] and the online travel industry [54]. The sequence of events under the agency selling schemes is illustrated in Figure 2 and described as follows: the manufacturer sets the retail price and pays a platform fee to the platform per unit sold, and then consumers make their purchasing decisions. Such a kind of a constant fee contract is also widely used in previous studies, such as Zhang et al. [5], Jiang et al. [56], and Mantin et al. [57]. Throughout this paper, to make all members participate in the supply chain, the platform fee is not too large; that is, . Similar to Hao and Fan [43] and Tan and Carrillo [44], Section 6.2 investigates a case in which the platform fee is a proportion of the selling price in the agency model. We show that the main insights derived from the baseline model remain robust under a proportional platform fee. Moreover, Section 6.4 discusses the situation where the platform fee is an endogenous variable that is determined through negotiations between the manufacturer and platform. We find that the main insights remain qualitatively unchanged.

Figure 1.

The sequence of events under the wholesale selling scheme.

Figure 2.

The sequence of events under the agency selling scheme.

3.2. Consumer Behavior Analysis and Demand Functions

Following Bolton et al. [21], fairness is defined as a judgment of whether an outcome and/or the process to reach an outcome for the decision-maker are reasonable, acceptable, or just. According to the type of decision-maker, fairness concern can be divided into the following categories: distributional-induced fairness concern (Fehr and Schmidt [15]), peer-induced fairness concern (Ho and Su [38]), and consumer fairness concern (Yi et al. [19]). In this paper, we mainly investigated the latter category. Generally, in the existing literature, there exist several types of consumer fairness concerns. In a monopoly setting, consumers are concerned about the past prices, peer’s prices in the same market, and seller’s profit (Guo [17]; Bolton et al. [21]; Ho and Su [38]). In a competitive setting, consumers may be concerned about competitor prices. The current research focuses on discussing a monopoly setting in which there is a supply chain composed of an upstream manufacturer that provides products, a downstream platform that intermediates sales, and a continuum of consumers with fairness concerns. The consumers may compare their payoffs with seller’s profits and may choose not to buy a product if the product’s pricing appears to be greedy and is believed to result in high returns for the seller. (This paper concentrates on consumer fairness concern when the relevant reference point for consumer fairness perception is the seller’s profit margin. The reference point for consumer fairness perception may be the suppliers/workers being paid low wages to make the product from the transaction with the fairness concerned consumers. Such a kind of consumer fairness concern is beyond the scope of the current research.)

Some empirical surveys show that a significant proportion of consumers in sectors such as smartphones, furniture, and shoes consider a firm’s profit margin when making a purchase decision (Liu et al. [52]). Empirical evidence and behavioral research suggest that, when a firm’s profit margin is too high relative to consumer surplus, consumers may perceive the firm’s prices as unfair (Guo and Jiang [18]). For example, Bolton et al. [21] found that consumers’ perception of price fairness is influenced by their beliefs about the seller’s profit margin. Guo and Jiang [18] designed a survey of 170 students. For students deriving $100 of usage benefits from a product priced at $95, they found that, when the participants know that the firm’s unit cost is $20 or $30, more than 60% of them decide not to buy the product, even though a purchase could give them a $5 economic surplus. The above empirical, experimental, and anecdotal evidence all indicate that consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP; i.e., their overall utility from a product) depends not only on their monetary payoff (i.e., economic surplus) but also on the firm’s profit margin.

As shown in the Introduction, in several practical industries, such as the pharmaceutical industry, the online hotel industry, and the luxury goods industry, the consumer may give up buying the product even when the buying behavior leads to a higher monetary payoff than no purchase if the transaction is unfair. That is, consumers’ purchase decisions reflect their utility maximization, which may take into account both the monetary payoff and fairness concern. Therefore, the net utility of consumers includes both the benefits obtained in the transaction and the utility brought by fairness concerns. Before buying, the fairness-minded consumer cares about not only the positive monetary payoff derived from the purchased product but also compares their consumer surplus with the profit of the product retailer. If they feel that it is fair, then they are willing to purchase the product. However, if the commercial transaction is deemed unfair, then they may be reluctant to buy. Note that, in our research setting, the product seller may be the manufacturer or the platform.

When the platform uses the wholesale selling scheme, the positive monetary payoff for the consumer is , where is a reservation value and is a retail price determined by the platform. Following Yi et al. [19], Harutyunyan et al. [39], and Ho et al. [58], the reservation value is uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. When the platform adopts the agency selling scheme, the positive monetary payoff for the consumer is , where is a reservation value and is a retail price determined by the manufacturer [59].

The fairness-minded consumer also compares his/her gain against the profit margin of the supply chain. In Fehr and Schmidt’s framework, both advantageous and disadvantageous inequity should be considered [15]. However, based on the data obtained from automobile dealers in the US and The Netherlands, Scheer et al. [60] empirically found that the US dealers care only about disadvantageous inequity. Such a conclusion is also reached by Guo [17] and Guo and Jiang [18]. Therefore, we modeled the unfair transaction from the perspective of disadvantageous inequity.

Based on the above discussion, the fairness-minded consumers’ net purchase utility consists of the following two parts: the positive monetary payoff and the negative unfairness perception. Following Guo [17], Guo and Jiang [18], Yi et al. [19], Diao et al. [42], and Chen et al. [61], the purchase utility function of the consumer with fairness concerns under the wholesale selling scheme is , where is the monetary payoff derived from a product, and measures the difference between the seller’s profit margin and the consumer surplus. Here, represents the intensity of the consumer’s fairness concerns. The larger the , the stronger the fairness concerns of the consumer; that is, the greater the negative impact of perceived unfairness on the consumer’s utility. This utility specification captures the notion that consumers use the firm’s profit margin as a fairness reference point. That is, the consumers experience disutility when their payoffs are lower than the firm’s profit margin in the transaction. Such a construction of the utility function can be also found in Harutyunyan et al. [39], Yu et al. [40], Yang et al. [62], and Chen and Cui [63].

Similarly, when the platform adopts the agency selling scheme to sell the manufacturer’s product, the purchase utility function of the fairness-minded consumer is , where the monetary payoff derived from a product is . The impact of consumer fairness concern on its utility is measured as . The total utility of consumers consists of the utility generated in the transaction and the perception of fairness preference. Consumers will only buy a product if its total utility is non-negative; that is, or .

4. Analysis

This section presents the equilibrium analysis of the conventional wholesale selling scheme and the novel agency selling scheme. Superscripts and denote the manufacturer and the platform, respectively. Similar to Ho et al. [38] and Li et al. [64], we adopted backward induction to obtain the optimal solutions for the two game-theoretical models. We first discuss the wholesale selling scheme.

4.1. Wholesale Selling Scheme

Under the wholesale selling scheme, for a known retail price of the product, consumers weigh whether the product transaction is fair and decide whether to buy the product. Consumers buy the product if and only if consumers can enjoy non-disutility during the product transaction. That is,

Following Yi et al. [19], before product buying, consumers will form a reservation price ; that is, . Assume that the consumer’s monetary payoff is greater than the manufacturer’s profit margin; that is, . Then, we have . Thus, . Substitute into the inequality . We obtain that . Further, we can know that , which contradicts with the common sense that . Therefore, . Then, we have

According to the theory of rational expectation equilibrium (e.g., [19,32,33]), the expectation of one member to other members in the supply chain is consistent with the actual situation. When the platform sets the retail price of the product, it will form the expectation of the consumer’s reservation price. If the retail price of the product is higher than the consumer’s reservation price, the demand for the product is 0. Therefore, the manufacturer’s optimal price for the product is the consumer’s reservation price . From Equation (2), we have . Consumers will purchase one product if , i.e., . Note that the reservation value is uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. Thus, under the wholesale selling scheme, the fairness-minded consumer’s demand function is .

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the manufacturer first determines the product’s wholesale price , and then the platform lays down the product’s retail price . The optimization problems of the manufacturer and the platform are shown as follows:

The equilibrium results under the wholesale selling scheme are given in Lemma 1.

Lemma 1.

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the wholesale price and the platform determines the retail price . The market share is . The profits of the manufacturer, platform, and supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

All proofs are given in the Appendix A. Lemma 1 shows that the optimal wholesale price does not depend on , whereas the optimal retail price, supply chain system’s profit, and platform’s profit all decrease with . On the one hand, the wholesale price set by the upstream manufacturer is a constant value that does not depend on . Essentially, the platform has full pricing power; they will make decisions based on the intensity of the fairness concern under the wholesale selling scheme. However, the manufacturer decides on a wholesale price to maximize profit, which is independent of the fairness concern intensity. The above results also appear in previous literature, such as Tan et al. [6] and Hao and Fan [43]. On the other hand, the higher the degree of concern about fairness, the more sensitive consumers are to inequality in transactions. Under such a situation, the platform is unable to set a higher retail price. Therefore, when consumers become more fairness-minded and selling incentives are reduced, the platform will undoubtedly be worse off under the wholesale selling scheme. The profit loss for the platform will make the supply chain system worse off.

4.2. Agency Selling Scheme

Under the agency selling scheme, for a known retail price of the product, consumers weigh whether the product transaction is fair and decide whether to buy the product. Consumers buy the product if and only if consumers can enjoy non-disutility during the product transaction. That is,

Following Yi et al. [19], before product buying, a consumer will form a reservation price ; that is, . Assume that the consumer’s monetary payoff is greater than the manufacturer’s profit margin; that is, . Then, we have . Thus, . Substitute into the inequality . We obtain that , which contradicts with the common sense that a platform fee is a positive number. Therefore, . Then, we have

According to the theory of rational expectation equilibrium (e.g., [19,32,33]), the manufacturer’s optimal price for the product is the consumer’s reservation price . From Equation (4), we have . Consumers will purchase one product if , i.e., . Thus, under the agency selling scheme, the fairness-minded consumer’s demand function is .

Under the agency selling scheme, the e-commerce platform permits the manufacturer to sell its products to consumers directly and charges a platform fee for each sale. Following Zhang et al. [5], Jiang et al. [56], and Hagiu and Wright [65], the platform fee is a fixed per-transaction fee. In the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer sets the retail price and pays a platform fee to the platform per unit sold. The manufacturer maximizes its profit by determining the retail price given the platform fee predetermined by the platform owner; that is,

Based on the first-order condition, the equilibrium results under the agency selling scheme are summarized in Lemma 2.

Lemma 2.

Under the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the retail price . The market share is . The profits of the manufacturer, platform, and supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

Similar to Lemma 1, Lemma 2 shows that, when the fairness concern intensity is high, the platform’s profit and the retail price are reduced. Moreover, Lemma 2 points out that, when consumers pay more attention to fairness, the market demand of the supply chain is lower. The reason is that a lower retail price leads to insufficient production by manufacturers, resulting in a decline in market demand.

Proposition 1.

Under the agency selling scheme,

- (a)

- The market demand decreases and the retail price increases with the platform fee .

- (b)

- The profits of the manufacturer and the supply chain system decrease with the platform fee . However, there exists a threshold value for the platform fee . If the platform fee is lower than the threshold value (i.e., ), the profit of the platform increases with , whereas, if the platform fee is higher than the threshold value (i.e., ), the profit of the platform decreases with .

Part (a) of Proposition 1 illustrates that, as the cost of the platform increases, the market demand decreases and the retail price increases. The intuition behind these results is as follows. The higher retail price makes consumers feel more inequitable during the transaction process. Therefore, more consumers give up the transaction to punish the greedy platform. Thus, under the agency selling scheme, the market demand decreases with the platform fee.

Interestingly, Proposition 1(b) shows a counterintuitive result. Generally, the platform benefits from the high platform fee. However, we show that this result is not always true. Proposition 1(b) shows an inverted U-shaped relationship between the platform’s profit and the platform fee. The driving force of this inverted U-shape results roots in two effects: a positive direct effect and negative indirect effect. On the one hand, a higher platform fee directly benefits the platform’s profit. On the other hand, as shown in Part (a) of Proposition 1, a higher platform fee causes the market demand to decrease, thus indirectly hurting the platform’s profit. Consequently, when the platform fee is lower than the threshold value (i.e., ), an increment in the platform fee will only trigger a modest market demand cut for the supply chain. In such a situation, the negative indirect effect on the platform is dominated by the positive direct effect. However, when the platform fee is larger than the threshold value (i.e., ), an increment in the platform fee will trigger a strong market demand cut for the supply chain. Thus, the higher platform fee makes the platform worse off. In such a situation, the positive direct effect on the platform is dominated by the negative indirect effect.

5. Comparison

Based on the research results in Section 4, this section compares the two selling schemes from five perspectives: market share, retail price, profit, consumer surplus, and social welfare. Next, we first discuss the comparison results from the perspective of market share.

5.1. Market Share

Proposition 2.

For a lower platform fee (i.e., ), the market share under the agency selling scheme is larger. Otherwise (i.e., , the market share under the wholesale selling scheme is larger.

Proposition 2 illustrates that there exists a threshold for the platform fee, above which, the agency selling scheme will reduce the market share for the e-commerce platform and, below which, it will increase the platform’s market share. Naturally, common wisdom from existing literature suggests that, due to the double-marginalization effect, the market share under the agency selling scheme is larger (see, Hao and Tan [3] and Geng et al. [45] for instance). However, in contrast to the results of the conventional literature in the absence of consumers’ fairness concern behavior (e.g., Tan et al. [6], Hao and Fan [43], and Tan and Carrillo [44]), we show that the wholesale selling scheme does not necessarily induce a lower market share compared with the agency selling scheme. The platform fee has two effects on the market share―a direct receding effect and an indirect enhancing effect. First, the direct receding effect leads to a reduction in the market share for the agency selling. Second, the higher the commission fee, the lower the retail price of the product. The lower retail price will increase the market share. We refer to this effect as the indirect enhancing effect. Therefore, for a lower platform fee (i.e., ), then the indirect enhancing effect dominates the direct receding effect, which, in turn, leads to the platform gaining more market share under the agency selling scheme. However, for a higher platform fee (i.e., ), the direct receding effect dominates the indirect enhancing effect. Thus, the wholesale selling scheme will create more market share.

5.2. Retail Price

Proposition 3.

For a lower platform fee (i.e., ), the retail price in the wholesale selling scheme is larger. Otherwise, (i.e., ), the retail price in the agency selling scheme is larger.

Previous literature in the absence of the fairness concern suggests that wholesale selling will always result in a higher retail price (e.g., [43,44]). In contrast to the above common wisdom, our results reveal that which selling scheme results in a high retail price depending on the platform fee. In particular, for a lower platform fee (i.e., ), the common finding is that the wholesale selling scheme always leads to a higher retail price hold. However, for a higher platform fee (i.e., ), the reverse result holds. Similar to the explanation of Proposition 2, the above result is caused by two effects—a direct effect and an indirect effect. The indirect effect of the platform fees on the retail price may be positive or negative. Specifically, for a higher platform fee (i.e., ), the indirect effect of the platform fee on the retail price is positive, and, therefore, the platform will set a higher retail price. For a lower platform fee (i.e., ), however, the indirect effect of the platform fee on the retail price is negative, and, therefore, the platform will decide on a lower retail price.

5.3. Profit

Based on the above comparison results for market share and retail price, we now provide an equilibrium selling scheme for the platform and the manufacturer and determine the conditions under which the supply chain participants can achieve a win-win situation. For simplicity, we denote two threshold values for the fairness concern intensity: these are and .

Proposition 4.

For comparing the platform’s profit under the wholesale selling scheme () and the agency selling scheme (), we have:

- (a)

- For a lower platform fee (i.e.,),

- (1)

- If the fairness concern intensity is relatively low (i.e., ), then;

- (2)

- If the fairness concern intensity is relatively high (i.e.,), then.

- (b)

- For a higher platform fee (i.e.,),

- (1)

- If the fairness concern intensity is relatively low (i.e.,), then;

- (2)

- If the fairness concern intensity is relatively high (i.e.,), then.

Proposition 4 illustrates that the platform’s optimal choice relies on two key factors: the intensity of fairness concern induced by the consumer’s utility inequity and the platform fee charged by the platform for each sale. In particular, Proposition 4(a) illustrates that, when the platform fee and the fairness concern intensity are both relatively low, the platform is inclined to use the wholesale selling scheme. However, for a lower platform fee and a higher fairness concern intensity, the platform will choose the agency selling scheme. The intuition driving this result is as follows. First, for a lower fairness concern intensity, a lower platform fee implies that the platform can only retain a small part of the revenue, which is not conducive to the platform’s adoption of the agency selling scheme. Second, when the fairness concern intensity is relatively high, as a rational economist, the platform will transfer the control rights for product pricing to the manufacturer to avoid suffering more loss. Consequently, the platform will use the wholesale selling scheme in this case.

More interestingly, Proposition 4(b) shows that, when the intensity of fairness concern is high enough (i.e., ), the platforms still tend to adopt the wholesale selling scheme. To pursue more market share, the platform or the manufacturer will aggressively reduce the retail price. This aggressive price reduction dominates the large platform fee in terms of its impacts on the platform’s profit under the agency selling scheme. Under such a situation, consequently, the platform still prefers the wholesale selling scheme. Alternatively, for a higher platform fee and a lower fairness concern intensity, the platform will choose the agency selling scheme.

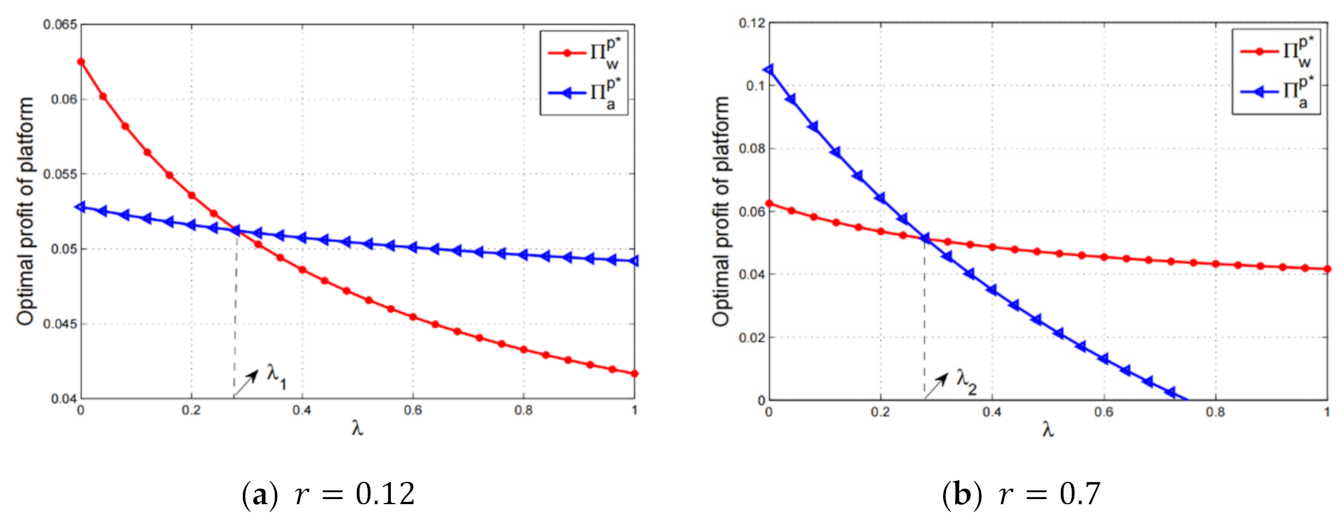

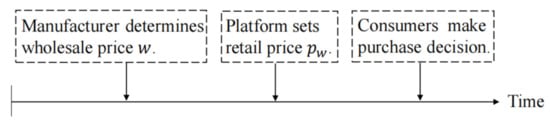

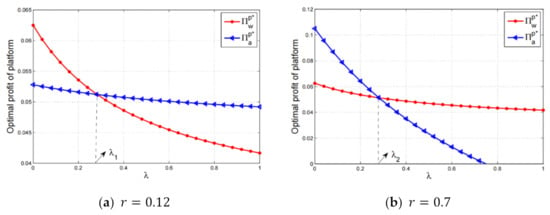

The above results theoretically prove that an increasing number of e-commerce platforms embrace the agency selling scheme. The results shown in Proposition 4 are shown in Figure 3. The results shown in Lemmas 1 and 2 illustrate that the optimal profits for the platform under the two selling schemes only depend on the fairness concern intensity and the platform fee. Therefore, we set and . Figure 3a,b correspond to the results shown in Proposition 4(a) and Proposition 4(b), respectively.

Figure 3.

Platform’s profit comparison.

From the platform’s perspective, Proposition 4 indicates some new managerial insights. Existing literature (e.g., [43,44]) investigated the monopoly case and showed that the agency selling scheme always dominates the wholesale selling scheme due to the revenue sharing structure in the agency selling scheme. However, under the same monopoly setting, we show that the agency selling scheme does not necessarily bring more benefits to the platform. Moreover, the agency selling scheme adopted by the platform is consistent with recent business development. Recently, several well-known e-commerce platforms in various industries, such as the travel agency platforms Priceline.com and Expedia.com in the travel industry, the retailing platforms Amazon and JD.com in the online retail industry, and group-buying platforms such as LivingSocial and Groupon in the online sales promotion industry, have begun to adopt the agency selling scheme.

Next, we compare the optimal profit for the upstream manufacturer under the two selling schemes to identify the optimal strategy for the manufacturer. For simplicity, we denote . The following proposition summarizes the comparison result.

Proposition 5.

From the perspective of the upstream manufacturer, we have:

- (a)

- When the platform fee is relatively low (i.e.,), then.

- (b)

- When the platform fee is relatively high (i.e.,1), then.

- (c)

- When the platform fee is in the intermediate range (i.e.,),

- (1)

- If the fairness concern intensity is sufficiently low (i.e.,), then;

- (2)

- If the fairness concern intensity is sufficiently high (i.e.,), then.

Proposition 5 illustrates that the manufacturer’s preference towards the two selling schemes depends on the platform fee and the fairness concern intensity. In particular, Proposition 5(a) indicates that, for a lower platform fee, the manufacturer will choose the agency selling. The manufacturer can gain more profits by using the agency selling scheme for a lower platform fee. Proposition 5(b) illustrates that, for a higher platform fee, the wholesale selling scheme is the dominant strategy for the upstream manufacturer. The driving force of this result is that the manufacturer will suffer more loss by using the agency selling scheme with a higher platform fee. Therefore, the manufacturer prefers to use the wholesale selling scheme in such cases.

However, for the intermediate platform fee, the optimal strategy may be more complex. In such a situation, the manufacturer should consider consumers’ fairness concern behavior when making the selling scheme decision. Proposition 5(c) illustrates that consumers’ desire for fairness in transactions may make the manufacturer deviate from the agency selling scheme to the wholesale selling scheme. When the fairness concern intensity is sufficiently high (i.e., ), then the improvement of the sense of fairness can dominate the market share reduction, and thus make the manufacturer better off. Consequently, the manufacturer may adopt the wholesale selling scheme in such a situation. The above results depend on interactions between the double marginalization effect on the supply side and consumers’ fairness concerns on the demand side.

Based on the results shown in Propositions 4 and 5, we have the following proposition.

Proposition 6.

(Win-win result) From the perspective of the whole supply chain system, we have:

- (a)

- For a lower platform fee (i.e.,),

- (1)

- If the intensity of fairness concern is relatively low (i.e., ), then the wholesale selling scheme is the dominant strategy for the whole supply chain;

- (2)

- If the intensity of fairness concern is relatively high (i.e., ), then both the upstream manufacturer and the downstream platform prefer to choose the agency selling scheme.

- (b)

- For a higher platform fee (i.e.,),

- (1)

- If the intensity of fairness concern is relatively low (i.e., ), then the agency selling scheme is the dominant strategy for the whole supply chain;

- (2)

- If the intensity of fairness concern is relatively high (i.e., ), then both the upstream manufacturer and the downstream platform prefer to adopt the wholesale selling scheme.

Proposition 6 shows that, under the low platform fee setting when the fairness concern intensity is relatively low, both the manufacturer and the platform prefer the wholesale selling scheme. Interestingly, when the intensity of fairness concern is relatively high, the agency selling scheme is the dominant strategy for the whole supply chain. Essentially, the double marginalization effect and consumers’ fairness concern effect lead to the above results. Specifically, when consumers are sensitive enough to unfairness in transactions (i.e., ), their fairness concern effect dominates the double marginalization effect. However, when consumers are not sensitive enough to inequity in transactions (i.e., ), then the double marginalization effect dominates the fairness concern effect.

Alternatively, under the high platform fee setting, Proposition 6(b) draws the opposite conclusion compared with Proposition 6(a). First, Proposition 6(b) reveals that, when the fairness concern intensity is low (i.e., ), the manufacturer is inclined to use the agency selling. This is because the manufacturer’s strategy depends on the fairness concern intensity when considering fairness-minded consumers. Second, Proposition 6(b) indicates that, when the fairness concern intensity is relatively high (i.e., ), then the manufacturer’s preference may switch from the agency selling scheme to the wholesale selling scheme. The intuition behind this result is as follows. A higher implies that consumers are sufficiently sensitive to unfairness during the transaction process. As shown in Proposition 3, the retail price in the agency selling scheme is higher when consumers are sufficiently sensitive to unfairness during the transaction process. A higher retail price of the product makes consumers feel that the transaction is more unfair. Note that, under such a situation, the manufacturer should be willing to provide more payoffs to the platform due to the higher platform fee. In order to avoid suffering more losses, the manufacturer should use the wholesale selling scheme. Therefore, when is relatively high (i.e., ), both the upstream manufacturer and the downstream platform prefer the wholesale selling scheme.

5.4. Consumer Surplus and Social Welfare

In this section, we discuss the implications of the platform’s selling scheme decision on consumer surplus and social welfare. Consumer surplus under the wholesale selling scheme is as follows:

whereas, under the agency selling scheme, it can be described as follows:

We compared consumer surpluses under the two selling schemes to determine which scheme is optimal for consumers; that is, whether consumers can gain more utility under the agency or the wholesale selling scheme. The comparison result is summarized in Proposition 7.

Proposition 7.

For a lower platform fee (i.e., ), consumers will be better off under the agency selling scheme. Otherwise (i.e., ), consumers will be better off under the wholesale selling scheme.

Proposition 7 shows that the comparison result for the two selling schemes in terms of consumer surplus depends on the platform fee. In general, consumer surplus depends on two factors: retail price and market share. However, based on the results shown in Propositions 2 and 3, consumer surplus in our model depends on three factors: retail price, market share, and platform fee. In particular, a lower platform fee (i.e., ) reduces the retail price and increases the number of consumers who buy the product (i.e., increasing the market share) under the agency selling scheme. Therefore, in such a situation, consumers gain more utility when the platform adopts the agency selling scheme. However, recall that the market share under the agency selling scheme may be smaller for a higher platform fee, which is shown in Proposition 2, and the retail price in the agency selling may be larger for a higher platform fee, which is shown in Proposition 3. The smaller market shares and higher retail prices hurt consumer surplus. Therefore, in such a situation, consumers gain more utility when the platform adopts the wholesale selling scheme. However, for a higher platform fee (i.e., , the reverse conclusion holds.

We then discuss the social welfare under the two pricing schemes. Following Tan and Carrillo [44] and Kwark et al. [49], social welfare is the sum of the profits of the manufacturer and e-commerce platform and consumer welfare. Therefore, the social welfare under the wholesale selling is shown as follows:

whereas social welfare under the agency selling is shown as follows:

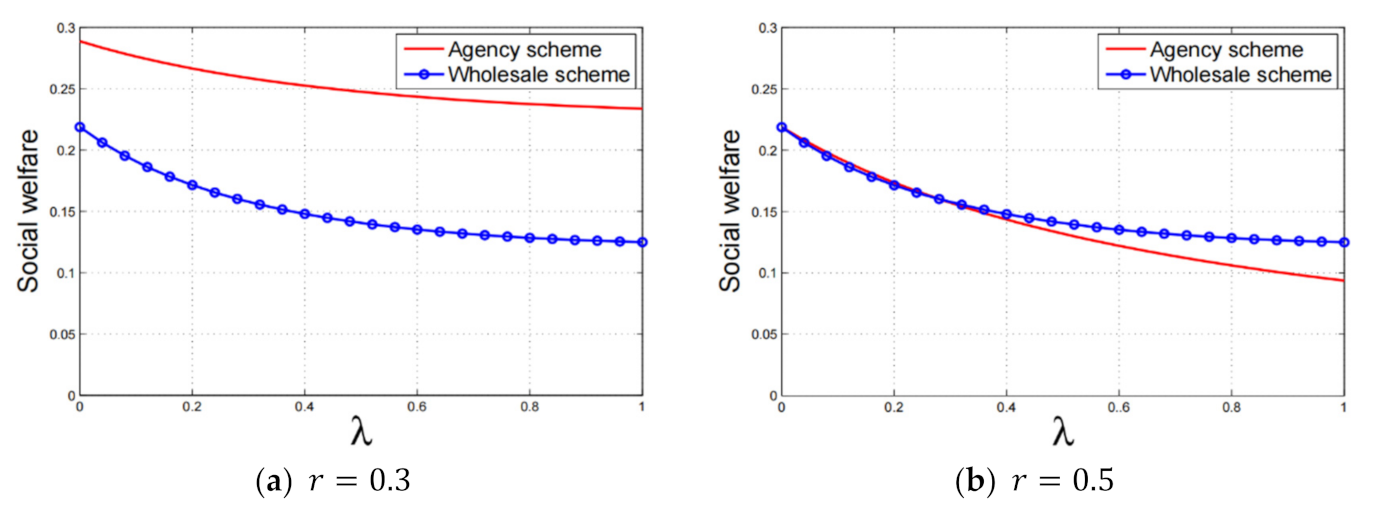

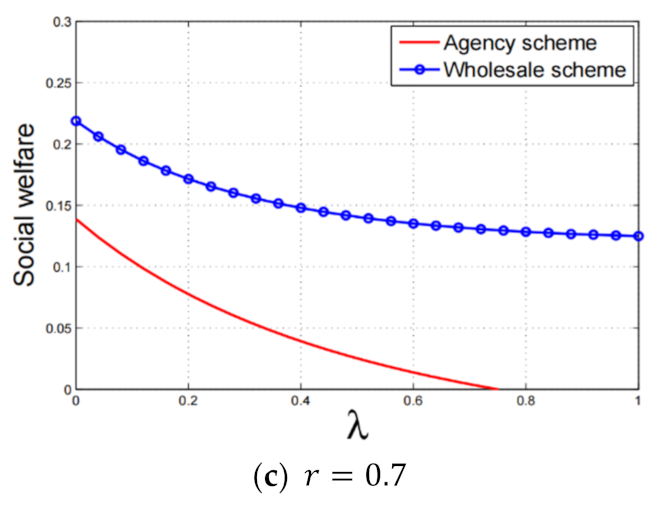

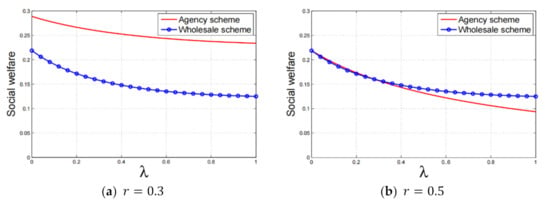

Due to the complex form of social welfare, analytical comparisons between the agency and wholesale selling schemes are very complicated. We use numerical analysis to gain managerial implications regarding the social welfare comparison. Figure 4 shows that social welfare under the two selling schemes decreases with the fairness concern intensity. First, for a lower platform fee, Figure 4a illustrates that the agency selling scheme outperforms the wholesale selling scheme in terms of social welfare. Second, when the platform fee is in the intermediate range, Figure 4b illustrates that the comparison between social welfare under the two selling schemes changes as varies. When the platform fee is in the intermediate range, both selling schemes can be used by the manufacturer and the platform. Under the setting of consumers’ fairness concerns, both parties’ choice depends on the fairness concern intensity. In particular, when the fairness concern is small enough, both parties will choose the agency selling scheme, as shown in Proposition 6, and consumers will obtain more utility under the agency selling scheme, as shown in Proposition 7. Therefore, the wholesale selling scheme results in the highest social welfare in this situation. When the fairness concern is large enough, the reverse conclusion holds; that is, the agency selling scheme results in the highest social welfare. Finally, when the platform fee is relatively high, Figure 4c illustrates that the wholesale selling scheme outperforms the agency selling scheme in terms of social welfare.

Figure 4.

Comparison of social welfare.

6. Extensions

This section investigates two extensions of our baseline model. Section 6.1 examines how the heterogeneous consumer behavior impacts the platform’s optimal selling scheme selection. In Section 6.2, we investigate the case in which the platform takes a proportion of the selling price in the agency selling scheme. Section 6.3 studies the situation where consumers care about fairness between the manufacturer’s profit and their own surplus. In Section 6.4, we discuss the endogenous commission fee. We find that the main conclusions presented in the baseline model remain qualitatively unchanged in the four extensions.

6.1. Consumer Heterogeneity

In the baseline model, all consumers have the same fairness concern intensity. In reality, however, the consumer market may be heterogeneous; that is, a proportion of consumers are fairness-minded, whereas others are fairness-neutral and focus on their economic surplus [18]. To describe these kinds of market practices, we next examine how the heterogeneous consumer behavior impacts the platform’s optimal selling scheme selection. Following the model in Guo [17], the consumer market consists of two segments in this extension. The first segment is fairness-minded consumers, and the fraction of such consumers is (1). If the transaction is deemed unfair, even if it results in a higher monetary payoff than not buying, the consumers in this segment may abandon the purchase. The other segment of consumers is fairness-neutral and may not care about whether the transaction is fair or not. The fraction of this segment is . The first segment is the fairness-minded segment, whereas the other segment is the fairness-neutral segment. The above model setup is consistent with empirical evidence that consumers’ perception of fairness of large US companies is heterogeneous [17]. Note that, when , this extension degenerates to the baseline model. Subscripts and denote the fairness-minded segment and the fairness-neutral segment, respectively.

For the fairness-minded segment, the utility function of a consumer is the same as that in the baseline model. Under the wholesale selling scheme, the utility function of the consumer is , whereas, under the agency selling scheme, the utility function of the consumer is . Here, the reservation value is uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. For the fairness-neutral segment, consumers may not care about whether the transaction is fair or not. Therefore, under the wholesale selling scheme, the consumer’s utility function is , whereas, under the agency selling scheme, the consumer’s utility function is . Here, the reservation value is uniformly distributed between 0 and 1.

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the fairness-minded consumers will buy one product if and fairness-neutral consumers will buy one product if . Note that the reservation values and are both uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. According to the theory of rational expectation equilibrium (e.g., [19,32,33]), the market share under the wholesale selling scheme is Similarly, under the agency selling scheme, the fairness-minded consumers will buy one product if and fairness-neutral consumers will buy one product if . Therefore, the market share under the agency selling scheme is .

6.1.1. Wholesale Selling Scheme

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the game-theoretical models for both parties of the e-commerce supply chain are the same as the baseline model. Based on the first-order condition and backward induction, the equilibrium results under the wholesale selling scheme are summarized in Lemma 3.

Lemma 3.

Under the wholesale selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the wholesale price and the platform sets the retail price The market demand is The profits of the manufacturer, the platform, and the supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

It can be verified that the optimal retail price and the platform’s optimal profit are identical to the equilibrium results presented in Lemma 1 by setting . Next, we discuss the effects of the fairness-minded segment fraction on the optimal retail price and the platform’s optimal profit.

Corollary 1.

Under and .

Corollary 1 shows that the retail price and the platform’s profit decrease with the fairness-minded segment fraction . This is because, the more the consumers are fairness-minded, the greater the likelihood that a transaction will be interrupted or broken. Therefore, the platform has no choice but to decrease the retail price to avoid losing consumers. The reduction in retail price, in turn, influences the decline in profits.

6.1.2. Agency Selling Scheme

Under the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer maximizes its profit by setting the retail price given the platform fee predetermined by the platform owner; that is,

Based on the first-order condition, the equilibrium results under the agency selling scheme are summarized in Lemma 4.

Lemma 4.

Under the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the retail price . The market demand is . The profits of the manufacturer, the platform, and the supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

Similar to Lemma 3, Lemma 4 degenerates to the counterpart Lemma 2 shown in the baseline model by setting . Next, we discuss the effects of the fairness-minded segment fraction on the equilibrium results under the agency selling scheme.

Proposition 8.

- (a)

- , , and .

- (b)

- If the fraction of the fairness-minded consumer is large (i.e., ), then . However, if the fraction of the fairness-minded consumer is small (i.e., ), then .

In line with Corollary 1, Proposition 8(a) shows that the retail price and the platform’s profit decrease with the fairness-minded segment fraction . Proposition 8(a) also illustrates that the market share decreases with . Intuitively, as increases, more transactions will break due to the unfairness in the transaction process. Therefore, the market share will decrease. Proposition 8(b) provides a new insight: when the fraction of the fairness-minded consumers is sufficiently large (i.e., ), the manufacturer’s profit increases with the fraction . Otherwise, the reverse relationship holds. The intuition behind this insight is as follows. On the one hand, intuitively, a larger induces the platform to set a lower platform fee, which, in turn, reveals that the transaction is fair, and then more consumers buy the product. The lower platform fee and the higher market share make the manufacturer gain more profit. Thus, a larger benefits the manufacturer’s profit. On the other hand, when the fraction of the fairness-minded consumers is small (i.e., ), then the platform has no incentive to reduce the platform fee. In such a case, consumers feel that the transaction is very unfair and then the transaction is more likely to break. Therefore, a smaller leads to a lower market share, which, in turn, hurts the manufacturer.

6.1.3. Comparison

The following corollary presents the comparison result about the market share.

Corollary 2.

If the platform fee is relatively low (i.e., ), then the market share under the agency selling scheme is larger than that under the wholesale selling scheme. If the platform fee is relatively high (i.e., ), then the market share under the wholesale selling scheme is larger than that under the agency selling scheme.

Corollary 2 illustrates that the comparison result about the market share depends on the platform fee. Particularly, for a lower platform fee, the agency selling scheme leads to more of a market share than the wholesale selling scheme. Otherwise, the reverse relation holds. Corollary 2 confirms that our insight in Proposition 2 under the baseline model remains qualitatively unchanged. We next summarize the comparison result about the retail price under the two selling schemes.

Corollary 3.

If the platform fee is relatively low (i.e., ), then the retail price under the wholesale selling scheme is larger than that under the agency selling scheme. If the platform fee is relatively high (i.e., ), then the retail price under the agency selling scheme is larger than that under the wholesale selling scheme.

Corollary 3 illustrates the comparison results in Proposition 3 under the baseline model; that is, a lower platform fee results in a larger retail price under the wholesale selling scheme, which remains qualitatively unchanged.

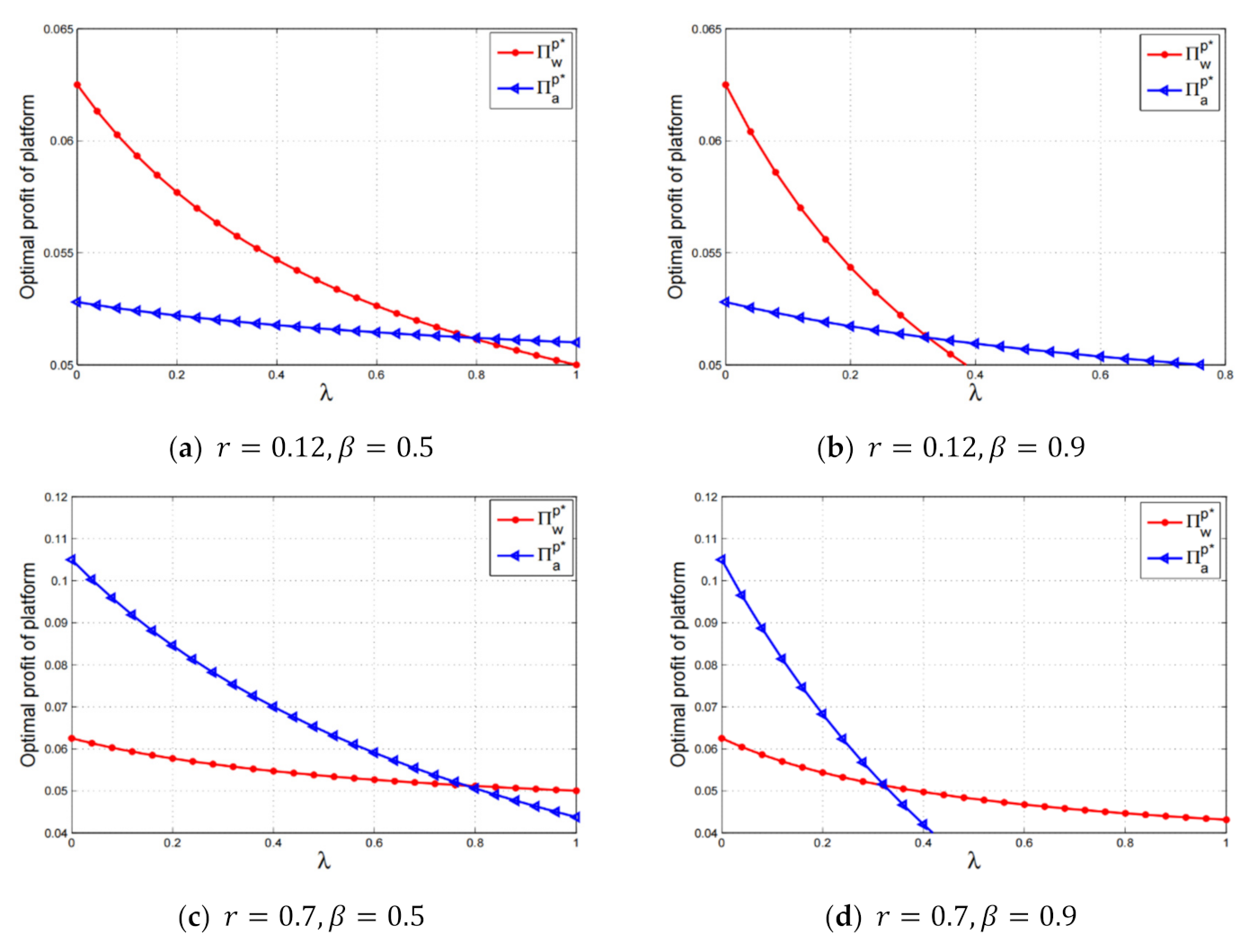

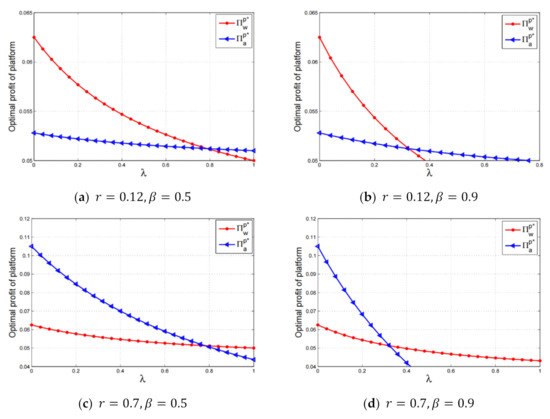

Due to the complexity of the expressions of the equilibrium profit, we present a numerical study. First, from the perspective of the platform, as can be seen from Figure 5a,b, when the platform fee is low enough, the lower fairness concern intensity induces more profit for the platform under the wholesale selling scheme. However, when the platform fee is low enough, the higher fairness concern intensity generates more profit for the platform under the agency selling scheme. Figure 5c,d indicate that, for a higher platform fee, the reverse relation of the above results holds. In summary, Figure 5 illustrates that the comparison of the platform’s profit is independent of the fraction of fairness-minded consumers. Such results illustrate the robustness of Proposition 4 in our baseline model. Second, from the perspective of the manufacturer, we can also verify that the conclusion presented in Proposition 5 remains qualitatively unchanged.

Figure 5.

Platform’s profit comparison with respect to fairness concerns.

In summary, the main conclusions presented in the baseline model remain qualitatively unchanged. Interestingly, this extension of consumer heterogeneity leads to a new finding: the manufacturer’s profit shows an inverted-U-shape curve relative to the fraction of the fairness-minded segment.

6.2. Proportional Platform Fee

In the baseline model, the platform fee is considered as a fixed fee per one transaction in the agency selling scheme. However, the platform will take a proportion of the selling price in the agency model [43,44]. This extension discusses the role of proportional platform fees during the transaction between the manufacturer and the platform. We denote as the proportional platform fee. The other notations remain the same as the baseline model. Therefore, the purchase utility function under the agency selling scheme is . Letting , we have . Consumers will buy one product if , i.e., . According to the theory of rational expectation equilibrium (e.g., [19,32,33]), under the agency selling scheme, the fairness-minded consumer’s demand function is . The manufacturer maximizes its profit by setting the retail price given the proportional platform fee predetermined by the platform owner; that is,

Based on the first-order condition, the equilibrium results under the agency selling scheme are shown in Lemma 5.

Lemma 5.

Under the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the retail price . The market share is . The optimal profits of the manufacturer, the platform, and the supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

Lemma 5 reveals the following findings. As expected, the profit of the manufacturer decreases with the proportional platform fee (i.e., ), whereas the platform’s profit increases with (i.e., ). In other words, the manufacturer will be worse off and the platform will be better off with the higher platform fee. However, the supply chain system’s total profit decreases with the proportional platform fee (i.e., ). Setting a higher commission fee is not a good choice for the whole supply chain system. When the platform obtains more of a profit from the transaction, the fairness consumers will buy fewer products, and may even not buy the product from the platform. Therefore, a moderate proportional commission fee is needed for the sustainable operation of the supply chain system.

For simplicity, we denote two threshold values for the fairness concern intensity; that is, and .

Proposition 9.

If and or and , then the agency pricing model benefits the manufacturer and the platform.

Proposition 9 shows that the fairness concern intensity and the commission fee are two key factors affecting the manufacturer’s and platform’s preferences with regard to the selling scheme. In particular, when these two factors are relatively high or low, the wholesale selling scheme outperforms the agency selling scheme in terms of the manufacturer’s and platform’s profits. Otherwise, the agency selling scheme is the dominant strategy for both participants. These results are consistent with Proposition 6 shown in the baseline model. Therefore, our main conclusions remain qualitatively unchanged when the platform fee is a proportion of the selling price in the agency model.

6.3. Fairness Concern about the Manufacturer’s Profit

In the baseline model, we have assumed that the fairness-minded consumers care about the fairness between the platform’s profit and their surplus. In this section, we investigate the situation where consumers care about fairness between the manufacturer’s profit and their surplus. Following Guo and Jiang [18] and Yi et al. [19], the purchase utility function of the consumer with fairness concerns under the wholesale selling scheme is , where is the monetary payoff derived from a product, and measures the influence of consumer fairness concern on its utility. Similarly, when the platform adopts the agency selling scheme to sell a product, the purchase utility function of the fairness-minded consumer is , where the monetary payoff derived from a product is . The impact of consumer fairness concern on its utility is measured as . Consumers will only buy a product if its total utility is non-negative; that is, or .

Similar to the baseline model, according to the theory of rational expectation equilibrium (e.g., [19,32,33]), the fairness-minded consumer’s demand function under the wholesale selling scheme and the agency selling scheme are and , respectively.

When the consumers care about fairness between the manufacturer’s profit and their surplus, the game-theoretical model for both parties of the e-commerce supply chain under the two selling schemes is the same as the baseline model. Based on the backward induction, we can obtain the following equilibrium results.

Lemma 6.

- (a)

- Under the wholesale selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the wholesale price and the platform determines the retail price . The market share is . The profits of the manufacturer, platform, and supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

- (b)

- Under the agency selling scheme, the manufacturer charges the retail price . The market share is . The optimal profits of the manufacturer, the platform, and the supply chain system are , , and , respectively.

Next, we further investigate the situation where the fairness-minded consumers care about the profits of both the manufacturer and the platform. Under such a situation, fairness-minded consumers may weigh on the fairness of trading for both the platform (say, ) and the manufacturer (say, ). Following Guo and Jiang [18] and Yi et al. [19], the purchase utility function of the consumer with fairness concerns under the wholesale selling scheme can be expressed as

and the purchase utility function of the consumer with fairness concerns under the agency selling scheme can be expressed as

Consumers will buy a product if and only if the total utility is non-negative; that is, or . Note that, when , this model degenerates to the baseline model, and when , this model degenerates to the model that we have investigated above.

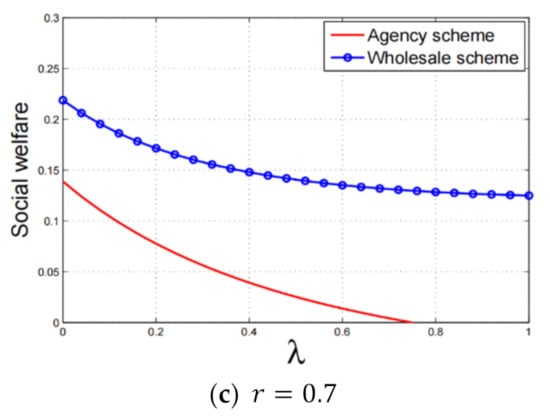

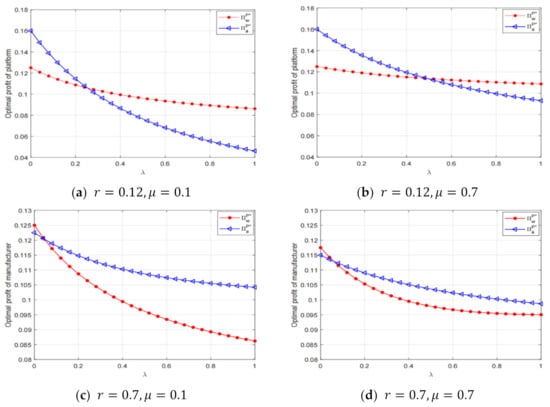

Now, owing to the complexity of the game-theoretical model, we carried out several numerical experiments to address the e-commerce platform’s selling scheme decision. In the numerical experiments, we set the fairness to weigh between the platform and the manufacturer as and to drive Figure 6. The results show that there is no difference in the selling scheme preference for the platform, as reflected in Figure 3 and Figure 6. In other words, the main conclusions presented in the baseline model remain qualitatively unchanged.

Figure 6.

Platform’s profit comparison with respect to fairness concerns.

6.4. Endogenous Platform Fee

In the main model, we assumed that the platform fee charged by the platform is an exogenous constant. A natural extension of this assumption is to investigate what factors may influence the platform fee. In this extension, we discuss the situation where the platform fee is an endogenous variable that is determined through negotiations between the manufacturer and the platform.

To reflect each party’s impact on the platform fee, we employed the standard Nash bargaining solution (Li et al. [66]), generalized to allow for asymmetric bargaining power. Let reflect the relative bargaining influence of the platform and represent the bargaining power of the manufacturer. As a result, the endogenous platform fee, , is the solution of the following Nash bargaining formulation:

where and are the profits of platform and manufacturer under the agency selling scheme, respectively.

The Nash bargaining solution and managerial insights are summarized as follows.

Proposition 10.

When the platform fee, , is determined through Nash bargaining:

- (a)

- The optimal platform fee is .

- (b)

- For , the optimal platform fee increases with the bargaining power of the platform (i.e., ) and decreases with the intensity of consumer fairness concern (i.e., ).

Proposition 10 provides several expected results (which lends confidence to the validity of the model). As expected, the first part of Proposition 10(b) illustrates that the optimal platform fee increases with the bargaining power of the platform. That is, the platform can obtain a higher revenue during the transaction with the manufacturer, as they have more bargaining power. The second part of Proposition 10(b) reveals that the optimal platform fee decreases with the intensity of consumer fairness concerns. The intuition behind this result is as follows. When the intensity of consumer fairness concern becomes large, the consumers are more unwilling to buy products from greedy firms. In order to avoid losing more consumers, the platform will take less from the supply chain system. Therefore, Proposition 10 is consistent with the main insight that a larger platform fee may be harmful to the platform in the presence of fairness-minded consumers.

7. Discussion