Abstract

Consumers can choose to buy products through various retail channels (e.g., online or in-store), resulting in a need for retailers to provide a well-integrated shopping experience. However, individual factors, such as a customer’s personality, can influence how a channel is perceived and, as such, can alter their subsequent behavior. Thus, it is critical for retailers to better understand personality-related influences and how these can affect a customer’s purchase channel decision. Against this background, the purpose of this structured review is to analyze the extant literature on the influences of personality traits on purchasing channel decisions. After extensive initial screening, 24 papers published in 2003–2021 were included in the analysis and synthesis phase of this literature review. The results show how personality traits (including Big Five factors and more fine-grained factors like playfulness) influence the choice of retail purchasing channels. Among other results, we find that online shopping intentions have been studied most as an outcome variable and that, in contrast to people high in openness to experience, people high in agreeableness are less likely to shop online. While we synthesize findings in the domains of mobile commerce, social commerce, mall shopping, and augmented and virtual reality as well, little research has compared the effects of personality traits on multiple channels. Based on our findings, we discuss managerial implications as well as directions for future research which are described in the form of a research agenda.

1. Introduction

The internet has drastically changed how customers shop. The vast amount of digital channels, such as online stores, mobile channels, and social media, has shaken up traditional retail practices [1]. A pressing issue for retailers is to provide a so-called omnichannel customer experience through the seamless integration of different retail channels [2,3]. In doing this, retailers can directly optimize some factors to shape customers’ shopping experiences, such as price or product quality [4]. However, a customer’s experience of company touchpoints or purchase channels is predominantly shaped by individual factors [5,6]. Thus, shopping-related decisions also strongly depend on individual factors [5]. A customer’s personality is among the most important individual factors that drive behavior [5,7,8].

Personality traits can be defined as “characteristics that are stable over time, [and] provide the reasons for the person’s behavior … They reflect who we are and in aggregate determine our affective, behavioral, and cognitive style” [9] (pp. 448–449). Personality traits have been found to influence general online and shopping behavior. For example, altruism and locus of control (the ability to control the outcome of a certain task) have been found to increase trust in crowdfunding [10]. Trust in crowdfunding then influenced the consumer’s intention to participate in crowdfunding [10]. Personality theories such as Costa and McCrae’s [11] Big Five personality traits, hereafter referred to as the Big Five, have been found to influence general shopping behavior [12], and general shopping motivations (e.g., bargaining behavior [13], shopping for enjoyment [14], and shopping for convenience [15]). Also, the Big Five predict materialism (the belief about the relevance of possessions in life), shopping-center selection, and excessive as well as compulsive buying [16,17,18,19]. Moreover, the Big Five affected privacy concerns and trust in smart speaker manufacturers which, in turn, influenced a customer’s experience of voice shopping performance [20]. Lastly, customers with a higher level of empathic concern reported greater satisfaction with online service providers and were more likely to help other online customers [21].

Considering the behavioral implications of an individual’s personality, it is no surprise that targeted advertising significantly increases advertising effectiveness [22,23,24] and that psychological factors such as a customer’s level of psychological distance towards a product should be considered in online sales promotions [25]. Moreover, the recent trend towards big data in retailing allows for the customization of services and products and helps with identifying and retaining valuable customers [26]. Hence, a retailer’s in-depth knowledge of possible influences of individual factors—of personality traits in particular—on retail purchasing decisions is crucial. To name an example of such an effect, a recent meta-analysis found that people high in individual playfulness were more likely to purchase online [27]. Calls have therefore been made in the retailing literature to study individual factors, such as personality, more systematically [28,29,30,31].

As a direct response to these calls, we conducted a systematic literature review analyzing the influences of personality traits on the choice of retail purchasing channels. To the best of our knowledge, no such review exists to date. Hence, the present article contributes to closing a significant gap in the literature. Specifically, we present a review of how customers’ personalities influence their selection of a specific purchasing channel (hereafter referred to as channel choice). We focus on direct relationships, but studies that examined indirect relationships were included in our review as well. Personality’s influence on channel choice is not always straightforward; rather, its influence can be complex. We address this complexity in the present paper. Against this background, this paper investigates the following research question (RQ): Which personality traits influence retail purchase channel choice behavior, and how?

The findings of this review are important for both practitioners and the academic community. Marketing and digital retail managers can use the findings to improve their customers’ omnichannel experience by creating customer-tailored messages across all retail channels. From a theoretical viewpoint, addressing this topic advances our understanding of the influence of various personality traits on channel choice behavior, thus providing insights for researchers in the fields of marketing and consumer psychology, as well as other disciplines such as information systems research. To motivate and instigate future studies, we further develop a research agenda based on the review results.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we describe the methodology of our literature review. Section 3 presents and discusses the results. In Section 4, we outline a research agenda and the managerial implications of our study. Finally, in Section 5, we describe the limitations of the review and provide a conclusion.

2. Literature Review Methodology

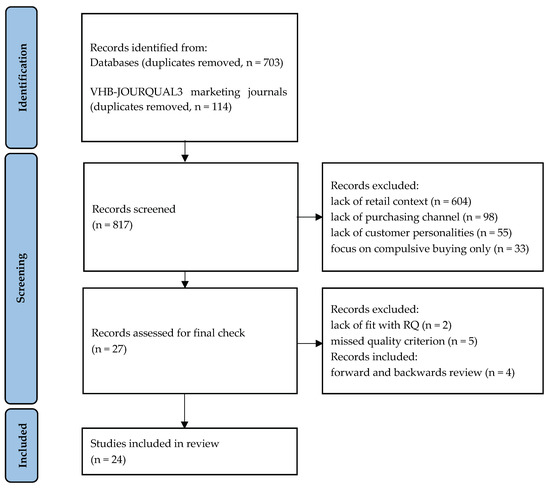

We applied the literature review approach of vom Brocke et al. [32] and Paul et al. [33]. In line with Paul et al. [33], the goal of this structured literature review is to (1) provide a state-of-the-art overview of the current literature and (2) formulate an agenda for future research to advance the research domain. Further, this review is classified as domain-based, focusing on empirical studies in a specific research domain [33]. To conceptually clarify the topic, it is, therefore, necessary to define the scope of our research. A customer typically has multiple touchpoints with a retailer, defined as any type of contact between the customer and the retailer throughout the customer’s journey [6]. However, purchase usually happens through one specific retail channel (e.g., purchasing a product online or buying it in a physical store). Hence, to answer the research question, the scope of this study is to review literature that focuses on personality traits and their influences on this particular purchase channel decision. To the best of our knowledge, no such review exists, making the domain applicable for an extensive, structured literature review [33]. Considering the framework by vom Brocke et al. [32], we provide a neutral analysis of empirical research outcomes. Figure 1 outlines our applied search strategy and selection process.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and selection process (adapted version of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram by Page et al. [34]).

We consulted the Web of Science and EBSCOhost databases to identify relevant studies. These databases include a wide range of research papers in the fields of marketing, business, information science, information systems, and psychology, among others. Moreover, we included 32 relevant A+, A, and B ranked marketing journals from the VHB-JOURQUAL3 ranking [35]. We used the generic search terms (“retail”) AND (“personality trait*”). Additionally, we consulted a landmark publication by Lemon and Verhoef [28] (2908 citations on Google Scholar, last access on 2 October 2021) on customer journeys in retailing to obtain channel-related keywords. Based on this publication, we identified the following keywords: (*catalog*)/(*channel*)/(*commerce)/(*direct mailing*)/(*mobile*)/(*online*)/(*store*) AND (“personality trait*”). We included the keywords (showrooming) as well as (webrooming), which are terms for searching in-store and buying online, and vice versa. To further include in-store/shop and shopping-related content, we searched for (shop*) AND (“personality trait*”). We did not limit the results to a certain search period. We reviewed titles and abstracts in the EBSCOhost database. In Web of Science, we specified “topic”. In both databases, we focused on English-language and peer-reviewed journal articles.

After removing duplicates, this initial search yielded 817 papers (last inquiry in October 2021). In the first step, we reviewed the title and abstract of each paper to identify relevant literature. We eliminated 604 papers that did not focus on retail and shopping contexts (e.g., with a focus on business-to-business, hospitality, or banking industries) as well as 98 papers that did not consider direct or indirect/mediated effects of the customer’s personality traits on their purchasing behavior (e.g., the evaluation of single website design features on the customer’s perception towards the website, or personality traits as moderators). Further, we excluded 55 papers that did not consider customers’ personality traits (e.g., papers that consider personalities of sales personnel) and 33 papers that focused on compulsive/impulsive buying behavior. When the title and abstract did not provide sufficient information to make the inclusion decision, we reviewed the introduction, theoretical model and corresponding constructs, and the conclusion for information on which to base the decision.

At this stage, 27 papers remained. Four papers were added through a forward and backward search, yielding a preliminary set of 31 papers. However, only journals ranked by SCImago (https://www.scimagojr.com/, accessed on 20 October 2021) were included in this review. Five articles did not meet this quality criterion and were excluded. Furthermore, we excluded Fenech [36], who studied wireless application protocol shopping, because this technology is outdated, as well as Lissitsa and Kol [37] because they studied products such as flight tickets and hotel room reservations rather than focusing on a pure retail and shopping context. Consequently, our search process resulted in a final set of 24 empirical papers for full-text review. Referring to additional information required by the protocol for structured literature reviews by Paul et al. [33], we reviewed the studies’ personality antecedents and retail channel choice as an outcome (for further information see Section 3.1). The evaluation was based on the content of each study, and the agenda proposal is structured as a gap analysis for future research. We report the findings in Section 3 and thematize the limitations of this review in Section 5.

3. Findings

3.1. Description of the Final Paper Set

In the final set of 24 publications, we identified 23 empirical studies that considered the effect of personality traits on channel choice. We further identified one meta-analysis examining the effects of personal innovativeness and individual playfulness on online purchasing intentions. The publication years ranged from 2003 to 2021. Between 2011 and 2021, 17 papers were published and seven were published between 2003 and 2010. Table 1 presents the list of journals from the present literature review.

Table 1.

Journal Distribution of Reviewed Articles.

A variety of purchase channels were researched. The majority of the studies and the meta-analysis included the online retail channel (11), followed by social commerce (4) and mobile commerce (3). Additionally, two studies researched virtual stores, and one study considered in-store/mall shopping. Three studies considered multiple channels, comparing traditional and mall shopping behavior with online shopping (2) as well as online shopping and augmented reality environments (1). Of the 23 empirical studies, 21 used a quantitative approach based on a survey while two conducted experiments/quasi-experiments with a survey.

For our analysis, we reviewed the personality traits in the studies’ theoretical frameworks along with the corresponding findings. Three papers [38,39,40], which followed a hierarchical model of motivation and personality by Mowen [41], investigated Elementary Traits, which we considered as personality traits. Moreover, three papers [42,43,44] used the terms personality factors, personality types, and personality characteristics, thereby denoting personality traits. In line with our research focus, we concentrated on direct relationships between personality traits and channel choice behavior (e.g., purchase intentions). Yet, in cases when the researchers did not test for direct effects (e.g., [45]) and only examined indirect effects, we included these indirect effects in our review as well.

In our analysis, we first present our research findings regarding the Big Five factors and the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) due to their popularity in both science and practice [46]. The section that follows (Section 3.4.) introduces all remaining personality traits and their influences on channel choice. See Table A1 for definitions of the personality traits discussed in this paper.

3.2. The Influence of the Big Five on Channel Choice

Within the reviewed papers, 13 articles studied at least one of the Big Five identified by Costa and McCrae [11]. Studies include direct and indirect effects of openness to experience, hereafter referred to as openness (11), extraversion (9), neuroticism/emotional instability (8), conscientiousness (8), and agreeableness (7).

Openness. Five studies considered the direct effects of openness on channel choice. Bosnjak et al. [38] surveyed 808 Croatian internet users and concluded that there is a small but significant direct and positive relationship between openness and online shopping intention. However, three studies could not replicate this direct relationship (McElroy et al. [46] survey, n = 153; Moslehpour et al. [40] survey, n = 316, Taiwan; Lixăndroiu et al. [47] quasi-experimental design, n = 121). Moreover, Kang and Johnson [39] found no significant direct relationship between openness and online social shopping (survey, n = 601, USA). Six studies did not research the direct but only indirect effects of openness on channel choice. Zhou and Lu’s [48] findings suggest that openness is related to trust, which, in turn, is related to mobile commerce intention (survey, n = 268, China). Wang et al. [42] found that people high in openness show a positive attitude toward online shopping, which is positively correlated with online shopping intention (survey, n = 473, Taiwan). Aydın [45] surveyed 269 individuals in Turkey and found that openness among participants was positively associated with hedonic (pleasure-driven) and utilitarian (task-oriented) motivations, which were positively associated with social commerce adoption. San-Martin et al. [49] conducted a survey with 366 Spanish game app players. The researchers proposed that openness was positively related to gaming self-efficacy (which was then related to online shopping self-efficacy and the intention to purchase online). However, their structural equation model did not support a relationship between openness and gaming self-efficacy. Using the theory of planned behavior, Piroth et al. [30] hypothesized that openness is related to the customer’s attitude towards online grocery shopping, which is related to online grocery shopping adoption (survey, n = 678, Germany, 70.2% of the sample had not used online grocery shopping); however, openness was not found to be related to attitude toward online grocery shopping. Moreover, Schnack et al. [50] conducted an experiment using a 3D virtual reality store environment. The researchers proposed that the higher a customer’s level of openness, the larger their share of private brand goods, which was then hypothesized to be related to virtual reality shopping time; however, the data did not support this relationship (experiment and survey, n = 113).

Extraversion. Five studies considered the direct effects of extraversion on channel choice. Mohamed et al. [51] found that extraversion was positively correlated with online shopping continuance intention (survey, n = 197, Malaysia). On the other hand, in a study of teens in the United States, Breazeale and Lueg [52] found that a high level of extraversion negatively influenced internet shopping behavior (survey, n = 583, USA) but positively affected mall shopping behavior (this group was referred to as Social Butterflies. Note: the researchers developed two additional groups which—for thematic reasons—are presented in the sections for further personality traits in the online (“Confident Techies”) and mall (“Self-Contained Shopper”) contexts). Lixăndroiu et al. [47], Bosnjak et al. [38], and McElroy et al. [46] did not find evidence for a direct link between extraversion and the intention to shop online or in AR contexts. Four studies did not research the direct but only indirect effects of extraversion on channel choice. Zhou and Lu [48] found that the relationship between extraversion and mobile commerce intention was fully mediated by trust and perceived usefulness. San-Martin et al. [49] found evidence that extraversion positively influences gaming self-efficacy which, in turn, was positively related to online shopping self-efficacy, as well as the intention to purchase game-related products online. Piroth et al. [30] hypothesized that extraversion is related to the customer’s attitude towards online grocery shopping, which should be related to online grocery shopping adoption; however, extraversion was not related to the attitudes toward online grocery shopping. Additionally, Schnack et al. [50] did not find a relationship between a customer’s level of extraversion and the number of impulse purchases they made in a 3D virtual reality store environment (the latter was then hypothesized to be related to virtual reality shopping basket size, shopping time, and amount spent).

Neuroticism. Five studies investigated the direct effects of neuroticism (note that Zhu et al. [53] researched neuroticism-anxiety without reference to the Big Five; hence, we will report on this finding in Section 3.4). As the structural equation model of Bosnjak et al. [38] shows, the study found a small but significant negative influence of neuroticism on the intention to shop online. In contrast, McElroy et al. [46] found a significant positive link between neuroticism and e-buying. Mohamed et al. [51], however, did not find that emotional stability (as the opposite pole of neuroticism) was associated with online shopping continuance intentions. Considering online and augmented reality environments, Lixăndroiu et al. [47] found that neuroticism had a negative effect on buying intentions in an augmented reality context, but no direct effect on regular online shopping. Additionally, four studies did not research direct but examined indirect effects of neuroticism. Zhou and Lu [48] reported that neuroticism showed a significant negative influence on a user’s trust in mobile commerce and whether they perceived it as useful, resulting in slower mobile commerce adoption. The researchers also concluded that trust and perceived usefulness partially mediated the effects of neuroticism on mobile commerce behavioral intentions. San-Martin et al. [49] revealed that neuroticism negatively influenced gaming self-efficacy which, in turn, was positively related to online shopping self-efficacy, as well as the intention to purchase game-related products online. Piroth et al. [30] hypothesized that neuroticism is related to the customer’s attitude towards online grocery shopping, which should influence online grocery shopping adoption; however, neuroticism was not found to be related to attitudes toward online grocery shopping. Furthermore, Schnack et al. [50] did not find an association between a shopper’s level of neuroticism and the number of impulse purchases they made in a 3D virtual reality store environment (the latter was then hypothesized to be related to virtual reality shopping basket size, shopping time, and amount spent).

Conscientiousness. Four studies considered the direct effects of conscientiousness in the context of online shopping—Bosnjak et al. [38], Lixăndroiu et al. [47], McElroy et al. [46], and Moslehpour et al. [40]. These studies, however, did not find evidence of a direct effect of conscientiousness on e-buying or intentions to shop online or in augmented reality environments. An additional four studies did not test direct effects but researched indirect effects of conscientiousness. Zhou and Lu [48] hypothesized a relationship between conscientiousness and mobile commerce intentions (via trust or perceived usefulness); however, the data did not support such a relationship. Further, San-Martin et al. [49] proposed, but did not find evidence, that conscientiousness was positively related to gaming self-efficacy (which was then related to online shopping self-efficacy and the intention to purchase online). Furthermore, Piroth et al. [30] suggested that conscientiousness is related to the customer’s attitude towards online grocery shopping, which should be related to online grocery shopping adoption; however, conscientiousness was not found to be related to attitudes towards online grocery shopping. Moreover, Schnack et al. [50] did not find a relationship between a customer’s level of conscientiousness and the number of impulse purchases they made in a 3D virtual reality store environment (the latter was then hypothesized to be related to virtual reality shopping basket size, shopping time, and amount spent).

Agreeableness. Three studies considered the direct effects of agreeableness on channel choice. Bosnjak et al. [38] found a small but significant negative relationship between agreeableness and online shopping intentions. However, this link was not confirmed by McElroy et al. [46] or Lixăndroiu et al. [47], who considered online and AR shopping environments. Four further studies did not test direct but researched indirect effects of agreeableness. Zhou and Lu [48] found evidence for a relationship between agreeableness and mobile commerce intention, which was partially mediated by trust and perceived usefulness. San-Martin et al. [49] revealed that agreeableness negatively affected gaming self-efficacy which, in turn, was positively related to online shopping self-efficacy, as well as the intention to purchase game-related products online. Piroth et al. [30] argued that agreeableness is related to the customer’s attitude towards online grocery shopping, which should be related to online grocery shopping adoption; however, agreeableness was not found to be related to attitudes toward online grocery shopping. Finally, Schnack et al. [50] did not find an association between a customer’s level of agreeableness and their product inspection times (the latter was hypothesized to be related to virtual reality shopping time).

3.3. The Influence of the MBTI on Channel Choice

The MBTI is named after Isabel Briggs Myers (1897–1980) and Katharine Cook Briggs (1875–1968) and is based on work by Carl Jung [54] on psychological personality types [55]. Two studies in this review considered MBTI personality characteristics. McElroy et al. [46] proposed a direct effect of MBTI personality characteristics on e-buying; however, they did not find evidence for this relationship. Barkhi and Wallace [44] did not test for direct effects but found indirect effects of MBTI personality characteristics on purchasing from a virtual store (survey, n = 257, USA). People with more intuitive orientations perceived higher ease of use of virtual stores. Further, people with greater extraversion and perceptive orientations reported higher levels of perceived peer influence when buying from a virtual store. However, people’s thinking orientations (e.g., a person’s preference to make decisions and link ideas through logical connections) did not influence the perceived virtual store usefulness. Perceived ease of use, usefulness, and peer influence positively affected attitudes toward and intentions to buy from a virtual store.

3.4. Further Personality Traits and Their Influence on Channel Choice

This section describes all remaining personality traits identified in our review, sorted by researched purchase channels.

Social Commerce. Four papers considered the effects of additional personality traits on social commerce intentions. In line with our research focus, we first present studies that tested the direct effects of personality on social commerce. Goldring and Azab [56] found that market mavens were more likely to use social media shopping than non-mavens (survey, n = 307, USA). Handarkho [29] did not find that trust directly influenced social commerce intentions (survey, n = 874, Indonesia). Moreover, Kang and Johnson [39] did not find a direct influence of arousal needs and material resource needs on social shopping intentions. Only testing indirect effects, Aydın [45] found that a person’s need for uniqueness was positively associated with socialization motivations. Further, the researchers considered impulsive buying as another personality trait and found that it was positively associated with hedonic and socialization motivations. Lastly, hedonic and socialization motivations were positively associated with social commerce adoption.

Online Commerce. Seven papers considered the effects of additional personality traits on the online channel choice. In line with our research focus, we first present studies that tested the direct effects of personality on online commerce. Wu and Ke [27] conducted a meta-analysis considering the direct effects of the personality traits of personal innovativeness (12 studies, n = 7338) and individual playfulness (eight studies, n = 3591) on online purchase intentions. Individual playfulness showed a significant positive effect while personal innovativeness did not. Moreover, Zhu et al. [53] compared the personality traits of online and traditional shoppers using the Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ, Zuckerman et al. [57]) and the Consumer Style Inventory (CSI, Sprotles and Kendall [58], survey, n = 440, China, online shoppers had to have shopped online at least once). The online customer group scored higher on the traits aggression-hostility, brand consciousness, and novelty-fashion consciousness, and lower on neuroticism-anxiety and time consciousness. The researchers did not find a difference for the traits activity, confused by overchoice, impulsive sensation seeking, perfectionism/high-quality consciousness, and sociability. In another study, Breazeale and Lueg [52] developed a shopper typology for teens from the United States. The Confident Techies group, for example, showed the highest levels of self-esteem, internet interpersonal communication, and internet shopping behavior (the other groups were Self-Contained Shoppers (see section “Mall”) and Social Butterflies (see section “Big Five/Extraversion”)). Further, Lixăndroiu et al. [47] defined the personality traits locus of control and buying impulsiveness and compared their effects on online and augmented reality shopping intentions; however, the researchers found that only buying impulsiveness showed a positive effect and only on online buying intentions.

Only testing indirect effects, Das et al. [59] found a full-mediation effect of concern towards web security on the relationship between trust and online purchase intentions (survey, n = 372, USA). The researchers concluded that the lower a person’s trust, the greater their concern with web security, which negatively affects their online purchasing intentions. Also considering indirect effects only, Wang et al. [42] found that the risk-taking propensity trait was related to attitudes toward online shopping, which, in turn, were related to the intention to shop online. Also considering the indirect effects of risk-taking propensity, along with the need for achievement of entrepreneurs, Yusoff et al. [60] found that both traits were positively related to perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, which were related to the intention to participate in e-commerce (survey, n = 302, Malaysia).

Mall Shopping. Two studies considered the effects of additional traits on the mall channel choice. Comparing online and mall shopping behaviors, Breazeale and Lueg [52] developed a typology for teens from the United States. The researchers concluded that Self-Contained Shoppers showed the lowest level of self-esteem and extraversion as well as the lowest level of mall shopping behavior (the other groups were Confident Techies (see section “Online Commerce”) and Social Butterflies (see section “Big Five/Extraversion”)). Only testing indirect effects, Khare et al. [61] found that coupon-prone customers had a significant positive perception of promotional offers (survey, India, n = 453). Furthermore, price-conscious customers reported a significant positive perception of discounts, promotional offers, and loyalty cards. Value consciousness showed no influence on the mentioned variables. However, a customer’s perception of discounts and promotional offers positively influenced their commitment to the mall.

Mobile Shopping. Two papers considered the effects of additional traits in a mobile purchase context. Aldás-Manzano et al. [43] found that the innovativeness, mobile affinity, and internet compatibility traits directly and positively influenced mobile shopping intentions (survey, n = 470, Spain). Mobile shopping intentions further showed a positive effect on mobile shopping patronage. In another study, Mahatanankoon [62] found that individual playfulness and personal innovativeness influenced mobile commerce intentions (survey, n = 296, USA), though these relationships were mediated by an “optimum stimulation level” (the level of mobile phone usage for complex tasks), as well as text message use.

Webrooming. One paper considered the effects of personality traits in a webrooming (searching online, buying offline) context. Aw et al. [63] defined need for touch, need for interaction, and price-comparison orientation as consumer traits (survey, n = 280, Malaysia). Their study revealed that all three traits were directly and positively related to webrooming intentions.

3.5. Summary of the Main Findings

To summarize, the Big Five have been studied the most, and both direct and indirect effects on channel choice have been found. Considering the direct effects, agreeableness showed a negative direct relationship [38] while extraversion [47,51] showed a positive direct effect on online shopping intention. In contrast, Breazeale and Lueg [52] compared mall and online shopping behavior of teens in the United States and concluded that teens with a high level of extraversion spent the most time and money at the mall and the least time online. Neuroticism showed both a direct positive [46] and a direct negative [38] effect on online shopping intentions, as well as a direct negative effect on buying intentions in an augmented reality context [47]. Further, openness showed a direct positive effect on online shopping intentions [38]. Researchers also considered a variety of indirect effects: for example, trust and perceived usefulness had indirect effects on the relationship between extraversion (full mediation) and neuroticism (partial mediation) on mobile commerce intention [48].

Importantly, our review also reveals that the findings are not always conclusive; some of the researchers could not find any effects of the Big Five on channel choice (see, for example, Piroth et al. [30]). This lack of consistency could be at least partly explained by the fact that the samples of the studies differed in sociodemographic makeup, such as age and gender ratio, as well as educational backgrounds. Further, the reviewed literature draws from a variety of cultural backgrounds; for instance, Piroth et al. [30] studied consumers in Germany, Zhou and Lu [48] based their study in China, Khare et al. [61] conducted their study in India, Moslehpour et al. [40] and Wang et al. [42] studied consumers in Taiwan, San-Martin [49] studied app game players in Spain, and Bosnjak et al. [38] surveyed consumers in Croatia. Hence, culture could also impact the effects of personality traits on purchase channel decisions (see also [61]). Additionally, differences in study findings could be caused by differences in the measurement scales used (e.g., Bosnjak et al. [38] used a German 22-item short version and McElroy et al. [46] used the full 240-item Revised Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness (NEO) Personality Inventory). We found that in addition to Big Five and MBTI factors, some research studied several other high-level traits, such as trust [29,48,59], as well as fine-grained traits, such as innovativeness [27,43,62]. Thus, our review reveals that conceptualization of a customer’s personality exhibits great variance in the extant literature. In Table 2 and Figure 2, we provide an overview of the reviewed studies as well as their findings on personality traits and their effects on channel choice.

Table 2.

Reviewed studies and their findings.

Figure 2.

Summary of significant findings of the influence of personality traits on channel choice behavior. In line with the RQ, we mainly report direct relationships between personality traits and purchase behavior/purchase intentions/willingness to purchase; only where no direct relationship was tested did we include indirect associations as well. Further, this figure reports significant findings only. Positive relationships, unless otherwise noted with “neg.”.

4. Research Agenda and Managerial Implications

4.1. Research Agenda

In this literature review, we analyzed and synthesized the influence of personality traits on channel choice. The following research agenda is framed to reflect the unanswered research questions and the topics identified as underrepresented topics by the literature review. Three major domains are presented: (1) additional examination of direct and mediated effects on the personality–channel relationship; (2) additional examination of purchase channels; and (3) methods used to research the personality–channel relationship.

Additional Examination of Direct and Mediated Effects in the Personality–Channel Relationship. From a large amount of research on customer experience, we know that personal factors, especially emotions [64,65,66,67,68,69], play an overarching role in a customer’s shopping experience. Researchers have argued that emotions can be separated into incidental (task-unrelated, highly influenced by personality) and integral (task-related) emotions [70]. Additionally, evidence indicates that emotions are the foundation of personality [71]. While the reviewed papers considered emotion-related constructs to some extent (e.g., ease of use and arousal), we suggest broadening the research on the role of incidental emotions (e.g., by including the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scale by Davis et al. [72]). Future studies could further examine the role of popular personality theories such as the Big Five in combination with shopping channel–specific characteristics, such as the customer’s need to touch a product in an omnichannel retailing context [63,73]. Furthermore, considering additional personality theories such as the HEXACO Scale (e.g., Lee and Ashton [74]) might be a fruitful avenue for future research.

In addition to emotional experiences, a wide range of additional mediators could be tested in the future. Present-day customers commonly consult more than one channel or touchpoint before making their purchase decisions [6,28]. In such situations, a fundamental question arises: How does a customer decide where to buy the product? Previous research has found that if a channel is perceived as advantageous, satisfaction and loyalty increase [75], and that perceived risks might exhibit a strong influence [76]. Hence, future research could investigate whether customers’ perceptions of the possible advantages and risks of a channel are shaped by their personalities. As a starting point, it is well-established that neurotic individuals perceive more risks than less neurotic people [77]. Further, culture has been found to influence personality (e.g., Europeans and Americans scored higher in extraversion than Asians and Africans [78]). Khare et al. [61] also found that a customer’s culture has a strong influence on how promotional offers and benefits of loyalty cards are perceived. Therefore, further investigations of the effects of culture on the personality–channel relationship might be a promising area for future research. Lastly, previous research has found that certain politeness strategies have a less favorable effect on a customer’s recovery after a service failure [79]. For example, an employee’s positive politeness strategy aiming to improve customers’ perceived empathy toward the retailer and its staff (vs. a main focus on work competencies) showed a negative influence on customers’ co-recovery after service failure [79]. Hence, future research could examine if these particular employee strategies work best for customers with certain personalities (e.g., a customer with high levels of extraversion customer might respond differently than a highly neurotic customer).

Additional Examination of Purchase Channels. Our review shows that online shopping intentions have been extensively researched while new, emerging technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and social commerce—but also traditional in-store shopping environments—are still under-researched Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a “new normal” with changes in customers’ shopping behaviors (e.g., staying away from crowded spaces [80] or changing touch habits in stores to minimize the risk of getting infected [80,81]). As an example, people prefer to use e-wallets over cash [80]. Hence, future researchers might consider the influence of personality within the domains of new shopping technologies (e.g., augmented reality) and the changes to shopping behavior caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., the accelerated use of e-wallets at the store). Additionally, in our review, only a few studies compared multiple purchase channels [47,48,52]; the majority of studies focused on only one channel. Yet, from the customer’s perspective, retail channels along the customer journey increasingly merge [28]. Future research should expand on topics such as the effects of personality traits in multiple channels to learn more about channel-specific particularities and their influences on the purchase channel decision process (e.g., online vs. in-store shopping intentions).

Methods Used to Research the Personality–Channel Relationship. Most empirical studies in our review used survey data to investigate the influence of personality traits on channel choice behavior. Thus, the results presented in this review are mostly based on self-report measures (except for one meta-analysis and two experiments/quasi-experiments). Given that self-reported data could be susceptible to multiple measurement biases (e.g., social desirability, subjectivity, common methods), complementing existing self-report data with other data sources (e.g., measurement of actual behavior or use of physiological measurement instruments when emotions are the focus) would help to strengthen the robustness of research findings [82,83]. From a research methods perspective, therefore, we make a call for more experiments, both in the laboratory and the field, as well as a greater variety of data collection techniques. In addition to the suggested complementary use of physiological measurements, analysis of clickstreams, computer mouse behavior, and smartphone interaction behavior (e.g., swiping) could be applied to the study of online purchase contexts [84]. We further call for field studies in which real-life retailers’ data, such as sales numbers, are used as outcome measures. Another promising future research domain lies within the recent trend of big data and its management. Hence, future researchers could explore how big data (e.g., from social media analytics) can help with predicting retail channel choices and increasing customer satisfaction [26].

4.2. Managerial Implications

This literature review can help marketing managers to develop new customer targeting approaches. Considering the vast number of personality traits shown to influence purchase channel choice, retailers can benefit from identifying a customer’s personality. There is an ever-increasing availability of mobile and social media information and big data approaches that are used to personalize and optimize services and increase customer satisfaction [26,85,86,87]. Hence, for marketing managers to develop a targeted omnichannel marketing strategy and integrated marketing communications, knowing about the effects of a consumer’s underlying cognitive, affective, and behavioral tendencies is crucial [88]. Against this background, the goal of this literature review was to provide an overview of personality-related effects on retail purchase channel tendencies. With this knowledge, it is possible for retail managers, for example, to set certain incentives in an attempt to shape a customer’s purchase channel decision (e.g., if retail managers know a customer has certain personality tendencies that lead them to purchase through a particular channel, the retailer can provide corresponding incentives [56,89]).

Moreover, tailoring advertising messages to personality traits has been found to increase advertising effectiveness [22,23,24]. It, therefore, follows that if a retailer manager knows that a customer with a certain personality trait shows a tendency toward low trust, for example, it is easier for the retailer to adopt a marketing message to limit risk and increase trust perceptions. Further, if a retailer knows which personality types are, for example, more likely to participate in certain shopping channels such as social or mobile commerce, then it is much easier to tailor marketing messages within these channels accordingly. Similarly, when considering the needs and motives of slow-adopting customers, retail managers can develop tailored strategies to help customers with the adoption process.

5. Limitations and Conclusions

The limitations of this study are mostly due to the review and categorization processes. Purposely, only papers within the retail domain and a channel choice context were reviewed. Papers focusing mainly on other areas (e.g., the financial and banking sector) were not considered. It is possible that relevant papers using different keywords were not considered in our research. However, to increase validity, we carefully developed keywords based on a highly cited landmark paper and applied specific categorization criteria. Still, if other researchers consider further relevant keywords, their studies would constitute a valuable complement to this review. Despite these limitations, this literature review examined a wide variety of retail customer personality literature and highlighted its influences on purchase channel choice behavior.

The major contributions of the present paper can be summarized as follows: First, it adds to the knowledge of the influences of personality traits on channel choice behavior. This study revealed that the Big Five factors were most researched in the online shopping context. As an example, some evidence suggests that people high in agreeableness showed lower intentions to shop online and people high in openness were prone to online shopping [38,42]; however, other researchers did not find these links (e.g., [46]). Moreover, people high in neuroticism were found to be more likely to shop online [46], while another study found the opposite effect [38]. Thus, drawing general conclusions about the direct influences of personality traits on channel choice must be done with caution. These inconclusive findings might be a consequence of the application of different measurement instruments, different demographic mark-ups, and different cultures. Importantly, our review also revealed that research has studied both high-level personality traits (such as the Big Five and the MBTI) and more fine-grained traits like innovativeness [27,43,62]. In Table 2 and Figure 2, we summarized the effects of identified personality traits on channel choice. Moreover, in the Appendix A of this article, we developed a list with definitions of the personality traits examined in the investigated papers.

Second, we outlined three possible domains for future research that were illuminated by our review results. Our study thoroughly documented that online shopping intentions were most researched as outcome constructs and that research considering augmented reality, virtual reality, in-store shopping, as well as studies considering multiple channels are still rare. Against the background of an increasing need for a well-integrated omnichannel experience [3,28], we made a call to broaden research comparing the effects of personality traits on multiple channels in today’s omnichannel environments. Moreover, based on the finding that mostly self-reported measures were used to address the influence of personality traits on channel choice (except for two papers that combined an experiment/quasi-experiment with a survey), we outlined the urgent need for a greater variety of methods and instruments in future research.

Third, and finally, we provided managerial implications for retail managers. Retailers can use the findings of this research to develop targeted omnichannel marketing strategies and messages as well as targeted advertising.

Author Contributions

R.R. and A.H. conceptualized the study. A.H. reviewed the literature under supervision of R.R. A.H. and R.R. wrote the manuscript together. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been conducted within the training network project PERFORM funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 765395. Note: This research reflects only the authors’ views. The Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Further Information

This review was not registered. The review protocol can be accessed upon request.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definitions of personality traits.

Table A1.

Definitions of personality traits.

| Personality Trait | Definition |

|---|---|

| Activity | “a need for general activity and impatience and restlessness” [53] (p. 394) |

| Aggression-hostility | “readiness to express verbal aggression, rude, thoughtless or antisocial behavior, vengefulness, spitefulness, a quick temper and impatience with others” [53] (p. 394) |

| Agreeableness | “to appreciate the values and beliefs of other people” [48] (p. 548) |

| Arousal needs | “the desire for stimulation” [39] (p. 691) |

| Brand consciousness | “oriented toward the expensive and well-known international or national brands and felt price was an indicator of quality” [53] (p. 395) |

| Buying impulsiveness | ”an unplanned purchase based on immediate gratification of needs“ [45] (p. 435) |

| Confused by overchoice | “When facing an abundant of information, they might easily get confused or upset“ [53] (p. 395) |

| Conscientiousness | “the extent to which an individual is dependable, concerned with details, and responsible” [48] (p. 548) |

| Coupon proneness | “is an increased propensity to respond towards an offer due to the positive effect of coupon form on purchase evaluation” [61] (p. 1099-1100) |

| Emotional stability | “People who are emotionally stable possess morality, sense of direction, loyalty, and empathy” [51] (p. 1459) |

| Extraversion | “Extraversion refers to high activity, assertiveness, and a tendency toward social behaviors” [51] (p. 1458) |

| Impulsive sensation seeking | “a lack of planning and a tendency to act quickly on impulse without thinking” [53] (p. 394) |

| Individual playfulness | “makes a person more likely to interact instinctively, creatively, and imaginatively with others and with objects” [27] (p. 87) |

| Internet compatibility | “the degree to which an innovation is consistent with the past experiences and needs of potential adopters” [43] (p. 742) |

| Internet interpersonal communication | “interaction with members of one’s social network concerning goods and services” [52] (p. 566) |

| Intuitive | “the Intuitive (N) type indirectly perceives ideas and associations from their unconscious and combines them with perceptions coming from the outside world” [44] (p. 318) |

| Locus of control | “the degree to which people believe that they have control over the outcome of events in their lives, as opposed to external forces beyond their control” [47] (p. 5) |

| Market mavens | “are savvy price shoppers who have a key sense of their role as influencers in the marketplace. Market mavens crave variety and novelty in their shopping and consumption experiences” [56] (p. 1) |

| Material resource needs | “the desire to possess material goods” [39] (p. 691) |

| Mobile affinity | “the attitudes of individuals towards the medium and its content” [43] (p. 741) |

| Need for interaction | ”to seek assistance and interaction with salespeople” [63] (p. 3) |

| Need for touch | ”refers to consumers’ inclination of evaluating product information through the haptic sensory system” [63] (p. 3) |

| Need for uniqueness | ”to establish a unique image in society that can provide them a distinct social image” [45] (p. 435) |

| Need of achievement | “Individuals who possess a high N of Ach [Need of Achievement] are more motivated when faced with challenging business environments, as they are more greatly compelled to achieve their performance targets than those with a low N of Ach [Need of Achievement]” [60] (p. 1830) |

| Neuroticism/neuroticism-anxiety | “an emotional upset, tension, worry, fearfulness, obsessive in decision, lack of self confidence and sensitivity to criticism” [53] (p. 394) |

| Novelty-fashion consciousness | “to gain excitement and pleasure from seeking out new things, sometimes, they were impulsive when purchasing“ [53] (p. 395) |

| Openness to experience | “individual’s willingness to consider alternative approaches, intellectual curiosity and enjoyment of artistic pursuits” [45] (p. 444) |

| Perceptive | “delays making decisions, talks to peers to get their opinion and synthesizes the opinion of peers as a basis of his or her decision” [44] (p. 319) |

| Perfectionism, high-quality consciousness | “to seek the very best quality products and had high standards and expectations for consumer goods” [53] (p. 395) |

| Personal innovativeness/innovativeness | “a trait that makes an individual want to try new information technology” [27] (p. 87) |

| Price consciousness | “product price evaluations are based on psychological interpretation of value-price relationship and internal reference price” [61] (p. 1099) |

| Price-comparison orientation | ”consumers who are highly price comparison-oriented are likely to search for information online prior to purchase in physical stores as the Internet enables the price comparison to be done easier and quicker, and the information acquired facilitates subsequent purchase decision” [63] (p. 4) |

| Risk-taking propensity | “psychological tendency for taking risk” [42] (p. 73) |

| Self-esteem | “confidence in and satisfaction with oneself” [52] (p. 566) |

| Sociability | “liking of big parties, interacting with many people and having many friends and intolerance for social isolation” [53] (p. 394) |

| Thinking | “prefers to use an impersonal process and makes decisions by linking ideas through logical connections” [44] (p. 318) |

| Time consciousness | “Consumers scoring high on this dimension made shopping trips rapidly and did not give much thought before shopping” [53] (p. 395) |

| Trust | “means people develop trust […] because they believe there are benefits for participating in interactions on the platform and this further increases their intentions to use” [29] (p. 313) |

| Value consciousness | “is a concern for paying low prices while subjected to some quality constraints” [61] (p. 1100) |

References

- Hänninen, M.; Kwan, S.K.; Mitronen, L. From the store to omnichannel retail: Looking back over three decades of research. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2021, 31, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From Multi-Channel Retailing to Omni-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Briel, F. The future of omnichannel retail: A four-stage Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 132, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Izogo, E.E.; Jayawardhena, C. Online shopping experience in an emerging e-retailing market. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccinelli, N.M.; Goodstein, R.C.; Grewal, D.; Price, R.; Raghubir, P.; Stewart, D. Customer Experience Management in Retailing: Understanding the Buying Process. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyser, A.; Verleye, K.; Lemon, K.N.; Keiningham, T.L.; Klaus, P. Moving the Customer Experience Field Forward: Introducing the Touchpoints, Context, Qualities (TCQ) Nomenclature. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horton, R.L. Some Relationships between Personality and Consumer Decision Making. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.K.; Barrick, M.R.; Scullen, S.M.; Rounds, J. Higher-order dimensions of the Big Five personality traits and the Big Six vocational interest types. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 447–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ricardo, Y.; Sicilia, M.; López, M. Altruism and Internal Locus of Control as Determinants of the Intention to Participate in Crowdfunding: The Mediating Role of Trust. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R. The Big Five, happiness, and shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooradian, T.A.; Olver, J.M. Shopping motives and the five factor model: An integration and preliminary study. Psychol. Rep. 1996, 78, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G. Shopping Motives, Big Five Factors, and the Hedonic/Utilitarian Shopping Value: An Integration and Factorial Study. Innov. Mark. 2006, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.-H.; Yang, Y.-C. The Relationship between Personality Traits and Online Shopping Motivations. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2010, 38, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coshall, J.T.; Potter, R.B. The Relation of Personality Factors to Urban Consumer Cognition. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 126, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Five-Factor Model personality traits, materialism, and excessive buying: A mediational analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2013, 54, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, J.C.; Spears, N. Understanding Compulsive Buying Among College Students: A Hierarchical Approach. J. Consum. Psychol. 1999, 8, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Yang, H.W. Passion for online shopping: The influence of personality and compulsive buying. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2008, 36, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawack, R.E.; Wamba, S.F.; Carillo, K.D.A. Exploring the role of personality, trust, and privacy in customer experience performance during voice shopping: Evidence from SEM and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaza, N.A. Personality Antecedents of Customer Citizenship Behaviors in Online Shopping Situations. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Kang, S.K.; Bodenhausen, G.V. Personalized Persuasion: Tailoring Persuasive Appeals to Recipients’ Personality Traits. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckles, D.; Gordon, B.R.; Johnson, G.A. Field studies of psychologically targeted ads face threats to internal validity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5254–E5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, H.S.; Bouchacourt, L.; Brown-Devlin, N. Nonprofit organization advertising on social media: The role of personality, advertizing appeals, and bandwagon effects. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. Exploring Consumers’ Buying Behavior in a Large Online Promotion Activity: The Role of Psychological Distance and Involvement. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ying, S.; Sindakis, S.; Aggarwal, S.; Chen, C.; Su, J. Managing big data in the retail industry of Singapore: Examining the impact on customer satisfaction and organizational performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Y.; Ke, C.C. An online shopping behavior model integrating personality traits, perceived risk, and technology acceptance. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2015, 43, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handarkho, Y.D. The intentions to use social commerce from social, technology, and personal trait perspectives: Analysis of direct, indirect, and moderating effects. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2020, 14, 305–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroth, P.; Ritter, M.S.; Rueger-Muck, E. Online grocery shopping adoption: Do personality traits matter? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L. Understanding Retail Experiences and Customer Journey Management. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Brocke, J.; Simons, A.; Niehaves, B.; Reimer, K.; Plattfaut, R.; Cleven, A. Reconstructing the Giant: On the Importance of Rigour in Documenting the Literature Search Process. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Verona, Italy, 8–10 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Academic Association for Business Research: VHB-JOURQUAL 3. Available online: https://vhbonline.org/vhb4you/vhb-jourqual/vhb-jourqual-3 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Fenech, T. Exploratory study into wireless application protocol shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2002, 30, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S.; Kol, O. Four generational cohorts and hedonic m-shopping: Association between personality traits and purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 21, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Galesic, M.; Tuten, T. Personality determinants of online shopping: Explaining online purchase intentions using a hierarchical approach. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.M.; Johnson, K.K.P. F-Commerce platform for apparel online social shopping: Testing a Mowen’s 3M model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Pham, V.K.; Wong, W.K.; Bilgiçli, I. e-Purchase Intention of Taiwanese Consumers: Sustainable Mediation of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. Sustainability 2018, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mowen, J.C. The 3M Model of Motivation and Personality; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, M. Shopping Online or Not? Cognition and Personality Matters. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2006, 1, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldás-Manzano, J.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. Exploring individual personality factors as drivers of M-shopping acceptance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhi, R.; Wallace, L. The impact of personality type on purchasing decisions in virtual stores. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2007, 8, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, G. Do Personality Traits and Shopping Motivations Affect Social Commerce Adoption Intentions? Evidence from an Emerging Market. J. Int. Commer. 2019, 18, 428–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.C.; Hendrickson, A.R.; Townsend, A.M.; DeMarie, S.M. Dispositional Factors in Internet Use: Personality versus Cognitive Style. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lixăndroiu, R.; Cazan, A.M.; Maican, C.I. An analysis of the impact of personality traits towards augmented reality in online shopping. Symmetry. 2021, 13, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. The Effects of Personality Traits on User Acceptance of Mobile Commerce. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martin, S.; Jimenez, N.; Camarero, C.; San-Jose, R. The Path between Personality, Self-Efficacy, and Shopping Regarding Games Apps. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnack, A.; Wright, M.J.; Elms, J. Investigating the impact of shopper personality on behaviour in immersive Virtual Reality store environments. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Hussein, R.; Zamzuri, N.H.A.; Haghshenas, H. Insights into individual’s online shopping continuance intention. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breazeale, M.; Lueg, J.E. Retail shopping typology of American teens. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, J.; Yeow, C.; Wang, W. Traditional and online consumers in China: A preliminary study of their personality traits and decision-making styles. Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.G. Psychological Types; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, P.R.; Hunton, J.E.; Bryant, S.M. Accounting Information Systems Research Opportunities Using Personality Type Theory and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, D.; Azab, C. New rules of social media shopping: Personality differences of U.S. Gen Z versus Gen X market mavens. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M.; Kuhlman, D.M.; Joireman, J.; Teta, P.; Kraft, M. A Comparison of Three Structural Models for Personality: The Big Three, the Big Five, and the Alternative Five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprotles, G.B.; Kendall, E.L. A Methodology for Profiling Consumers’ Decision-Making Styles. J. Consum. Aff. 1986, 20, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Echambadi, R.; McCardle, M.; Luckett, M. The effect of interpersonal trust, need for cognition, and social loneliness on shopping, information seeking and surfing on the Web. Mark. Lett. 2003, 14, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.N.H.B.; Zainol, F.A.; Ridzuan, R.H.; Ismail, M.; Afthanorhan, A. Psychological traits and intention to use e-commerce among rural micro-entrepreneurs in malaysia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1827–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Sarkar, S.; Patel, S.S. Influence of culture, price perception and mall promotions on Indian consumers’ commitment towards malls. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 1093–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatanankoon, P. The Effects of Personality Traits and Optimum Stimulation Level on Text-Messaging Activities and M-commerce Intention. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 12, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, E.C.X.; Kamal Basha, N.; Ng, S.I.; Ho, J.A. Searching online and buying offline: Understanding the role of channel-, consumer-, and product-related factors in determining webrooming intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Al-Nabhani, K.; Wilson, A. Developing a Mobile Applications Customer Experience Model (MACE)- Implications for Retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foroudi, P.; Jin, Z.; Gupta, S.; Melewar, T.C.; Foroudi, M.M. Influence of innovation capability and customer experience on reputation and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4882–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value With the Customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Sun, J.J. On the Experience and Engineering of Consumer Pride, Consumer Excitement, and Consumer Relaxation in the Marketplace. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, A.; Riedl, R. The Nature of Customer Experience and its Determinants in the Retail Context: Literature Review. In WI2020 Zentrale Tracks; Gronau, N., Heine, M., Krasnova Pousttchi, K., Eds.; GITO Verlag: Potsdam, Germany, 2020; pp. 1738–1749. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes, A.; Riedl, R. How to Measure Customers’ Emotional Experience? A Short Review of Current Methods and a Call for Neurophysiological Approaches. In Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation—Information Systems and Neuroscience. NeuroIS Retreat 2020; Davis, F., Riedl, R., Brocke, J.V., Léger, P.-M., Randolph, A., Fischer, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.T. Emotion and Rationality: A Critical Review and Interpretation of Empirical Evidence. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montag, C.; Panksepp, J. Primary Emotional Systems and Personality: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, K.L.; Panksepp, J.; Normansell, L. The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales: Normative Data and Implications. Neuropsychoanalysis 2003, 5, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Childers, T.L. Individual Differences in Haptic Information Processing: The “Need for Touch” Scale. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ashton, M.C. Psychometric Properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 2018, 25, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocarro, R.; Cortiñas, M.; Villanueva, M.L. Customer heterogenity in the development of e-loyalty. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamalul Ariffin, S.; Mohan, T.; Goh, Y.N. Influence of consumers’ perceived risk on consumers’ online purchase intention. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Rogalsky, C.; Simmons, A.; Feinstein, J.S.; Stein, M.B. Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Terracciano, A. Personality profiles of cultures: Aggregate personality traits. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Su, J.; Xiao, Y. The effect of employees’ politeness strategy and customer membership on customers’ perception of co-recovery and online post-recovery satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Qual. Innov. 2021, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, K.; Verhulst, N.; Brengman, M. How COVID-19 Could Accelerate the Adoption of New Retail Technologies and Enhance the (E-)Servicescape. In The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic; Lee, J., Han, S.H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 103–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dimoka, A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Davis, F.D. Research Commentary: NeuroIS: The Potential of Cognitive Neuroscience for Information Systems Research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, R.; Léger, P.-M. Fundamentals of NeuroIS—Information Systems and the Brain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln, M.; Jenkins, J.L.; Schneider, C.; Valacich, J.S.; Weinmann, M. How Is Your User Feeling? Inferring Emotion through Human-Computer interaction Devices. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Sundar, S.S. Proactive vs. reactive personalization: Can customization of privacy enhance user experience? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2019, 128, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, R. Personality segmentation of users through mining their mobile usage patterns. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2020, 143, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachl, C.; Au, Q.; Schoedel, R.; Gosling, S.D.; Harari, G.M.; Buschek, D.; Völkel, S.T.; Schuwerk, T.; Oldemeier, M.; Ullmann, T.; et al. Predicting personality from patterns of behavior collected with smartphones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17680–17687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser Payne, E.; Peltier, J.W.; Barger, V.A. Omni-channel marketing, integrated marketing communications and consumer engagement: A research agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 11, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmeling, C.M.; Moffett, J.W.; Arnold, M.J.; Carlson, B.D. Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 312–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).