Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Vaccine Coverage: Insights for Healthcare Professionals Focusing on Herpes Zoster in Mexico

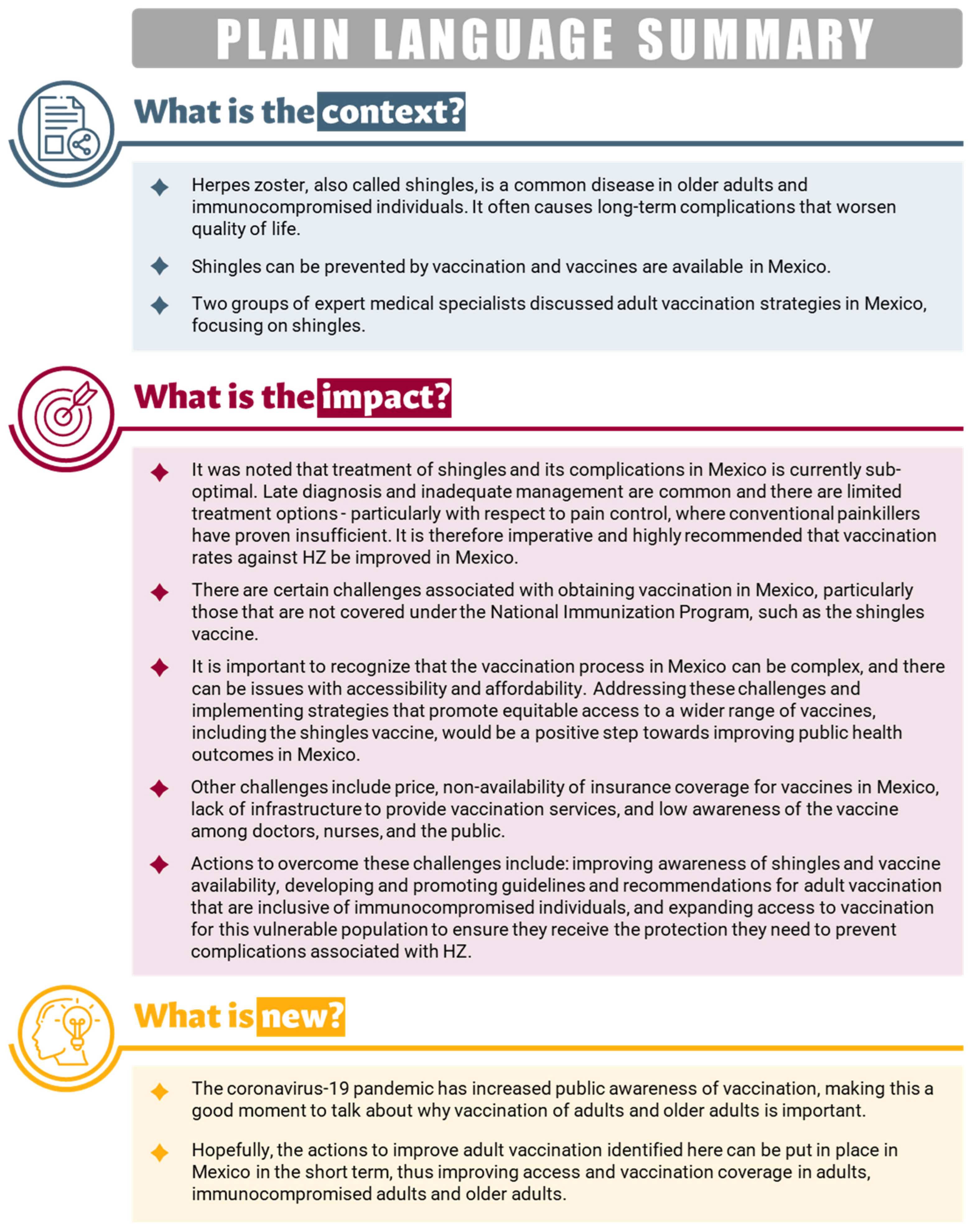

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Current Status of Adult Vaccination in Mexico

3. Why Is It Important to Vaccinate Against HZ in Mexico?

4. Insights from the Expert Panels

4.1. Patient Journey

4.2. Barriers to Vaccinating Against HZ in Mexico

4.3. Steps to Improve HZ Vaccination Rates in Mexico

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Trademark

References

- Johnson, R.W.; Alvarez-Pasquin, M.-J.; Bijl, M.; Franco, E.; Gaillat, J.; Clara, J.G.; Labetoulle, M.; Michel, J.-P.; Naldi, L.; Sanmarti, L.S.; et al. Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: A multidisciplinary perspective. Ther. Adv. Vaccines 2015, 3, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Shingles (Herpes Zoster). 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/hcp/clinical-overview.html (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- van Oorschot, D.; Vroling, H.; Bunge, E.; Diaz-Decaro, J.; Curran, D.; Yawn, B. A systematic literature review of herpes zoster incidence worldwide. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 1714–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panatto, D.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Rizzitelli, E.; Bonanni, P.; Boccalini, S.; Icardi, G.; Gasparini, R.; Amicizia, D. Evaluation of the economic burden of Herpes Zoster (HZ) infection. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2015, 11, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, M.; Prosser, L.A.; Rose, A.M.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; Harpaz, R. Aggregate health and economic burden of herpes zoster in the United States: Illustrative example of a pain condition. Pain 2020, 161, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.D.; Brenneman, S.K.; Newransky, C.; Sheffler-Collins, S.; Becker, L.K.; Belland, A.; Acosta, C.J. A cross-sectional survey of work and income loss consideration among patients with herpes zoster when completing a quality of life questionnaire. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.L.; Lal, H.; Kovac, M.; Chlibek, R.; Hwang, S.-J.; Díez-Domingo, J.; Godeaux, O.; Levin, M.J.; McElhaney, J.E.; Puig-Barberà, J.; et al. Efficacy of the Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Adults 70 Years of Age or Older. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, H.; Cunningham, A.L.; Godeaux, O.; Chlibek, R.; Diez-Domingo, J.; Hwang, S.-J.; Levin, M.J.; McElhaney, J.E.; Poder, A.; Puig-Barberà, J.; et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxman, M.; Levin, M.; Johnson, G.; Schmader, K.; Straus, S.; Gelb, L.; Arbeit, R.; Simberkoff, M.; Gershon, A.; Davis, L.; et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooling, K.L.; Guo, A.; Patel, M.; Lee, G.M.; Moore, K.; Belongia, E.A.; Harpaz, R. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiden, A.L.; Barratt, J.; Nyaku, M.K. Drivers of and barriers to routine adult vaccination: A systematic literature review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2127290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.-J.; Hung, M.-C.; Srivastav, A.; Grohskopf, L.A.; Kobayashi, M.; Harris, A.M.; Dooling, K.L.; Markowitz, L.E.; Rodriguez-Lainz, A.; Williams, W.W. Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populations—United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2021, 70, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Antiviral Use in EU/EEA Member States: Overview of Vaccine Recommendations for 2017–2018 and Vaccination Coverage Rates for 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 Influenza Seasons. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-antiviral-use-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Hastall, M.R.; Koinig, I.; Kunze, U.; Meixner, O.; Sachse, K.; Würzner, R. Multidisciplinary expert group: Communication measures to increase vaccine compliance in adults. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2024, 174, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M.; Caro-López, E.; Guerrero-Almeida, M.D.L.; Dehesa-Violante, M.; Rodríguez-Noriega, E.; García-Lara, J.M.; Medina-López, Z.; Báez-Saldaña, R.; Díaz-López, E.; Avila-Fematt, F.M.D.G.; et al. Results of the First Mexican Consensus of Vaccination in the Adult. Gac. Med. Mex. 2017, 153, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barreda-Zaleta, L.; Salinas-Lezama, E.; Díaz-Greene, E.; Rodríguez-Weber, F. La vacunación en el adulto en México. Med. Int. Méx. 2019, 35, 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Hervert, L.P.; Ferreira-Guerrero, E.; Díaz-Ortega, J.L.; Trejo-Valdivia, B.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Mongua-Rodríguez, N.; Hernández-Serrato, M.I.; Montoya-Rodríguez, A.A.; García-García, L. Vaccination coverage in young, middle age and elderly adults in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2013, 55 (Suppl. 2), S300–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hernández, H.; Zárate-Ramírez, J.; Kammar- García, A.; García-Peña, C. Estimation of vaccination coverage and associated factors in older Mexican adults. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo-Valdivia, B.; Mendoza-Alvarado, L.R.; Palma-Coca, O.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Téllez-Rojo Solís, M.M. National Survey of Vaccination Coverage (Influenza, pneumococcus and tetanus) in Mexican population of 60 years of age and older. Salud Publica Mex. 2012, 54, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardach, A.E.; Palermo, C.; Alconada, T.; Sandoval, M.; Balan, D.J.; Nieto Guevara, J.; Gómez, J.; Ciapponi, A. Herpes zoster epidemiology in Latin America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Glez, C.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Rojas, R.; DeAntonio, R.; Romano-Mazzotti, L.; Cervantes, Y.; Ortega-Barria, E. Seroprevalences of varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus in a cross-sectional study in Mexico. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5067–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Holst, A.; Cervantes-Apolinar, M.Y.; Favila, J.C.T.; Huerta-Garcia, G. Epidemiology of Herpes Zoster in Adults in Mexico: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, D.J.; Bardach, A.; Palermo, C.; Alconada, T.; Sandoval, M.; Guevara, J.N.; Gomez, J.; Ciapponi, A. Economic burden of herpes zoster in Latin America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2131167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampakakis, E.; Pollock, C.; Vujacich, C.; Toniolo Neto, J.; Ortiz Covarrubias, A.; Monsanto, H.; Johnson, K.D. Economic Burden of Herpes Zoster (“culebrilla”) in Latin America. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 58, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© GSK plc. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cervantes-Apolinar, M.Y.; Guzman-Holst, A.; Mascareñas De los Santos, A.; Macías Hernández, A.E.; Cabrera, Á.; Lara-Solares, A.; Abud Mendoza, C.; Motola Kuba, D.; Flores Díaz, D.F.; Salgado Gomez, F.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Vaccine Coverage: Insights for Healthcare Professionals Focusing on Herpes Zoster in Mexico. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121441

Cervantes-Apolinar MY, Guzman-Holst A, Mascareñas De los Santos A, Macías Hernández AE, Cabrera Á, Lara-Solares A, Abud Mendoza C, Motola Kuba D, Flores Díaz DF, Salgado Gomez F, et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Vaccine Coverage: Insights for Healthcare Professionals Focusing on Herpes Zoster in Mexico. Vaccines. 2024; 12(12):1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121441

Chicago/Turabian StyleCervantes-Apolinar, María Yolanda, Adriana Guzman-Holst, Abiel Mascareñas De los Santos, Alejandro Ernesto Macías Hernández, Álvaro Cabrera, Argelia Lara-Solares, Carlos Abud Mendoza, Daniel Motola Kuba, Diana Fabiola Flores Díaz, Fernanda Salgado Gomez, and et al. 2024. "Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Vaccine Coverage: Insights for Healthcare Professionals Focusing on Herpes Zoster in Mexico" Vaccines 12, no. 12: 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121441

APA StyleCervantes-Apolinar, M. Y., Guzman-Holst, A., Mascareñas De los Santos, A., Macías Hernández, A. E., Cabrera, Á., Lara-Solares, A., Abud Mendoza, C., Motola Kuba, D., Flores Díaz, D. F., Salgado Gomez, F., Castro-Narro, G. E., Nieto, J., Mata-Marín, J. A., Barba Gómez, J. F., Tinoco, J. C., Calleja Castillo, J. M., Contreras Serratos, M. M., Castellanos Ramos, N., Rosas Carrasco, O., ... Huerta García, G. C. (2024). Challenges and Opportunities for Adult Vaccine Coverage: Insights for Healthcare Professionals Focusing on Herpes Zoster in Mexico. Vaccines, 12(12), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121441