Assessment of the Methods Used to Develop Vitamin D and Calcium Recommendations—A Systematic Review of Bone Health Guidelines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study (Guideline/Policy Statement) Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Assessment of Guideline Development Methods

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.6. Role of the Funding Source

3. Results

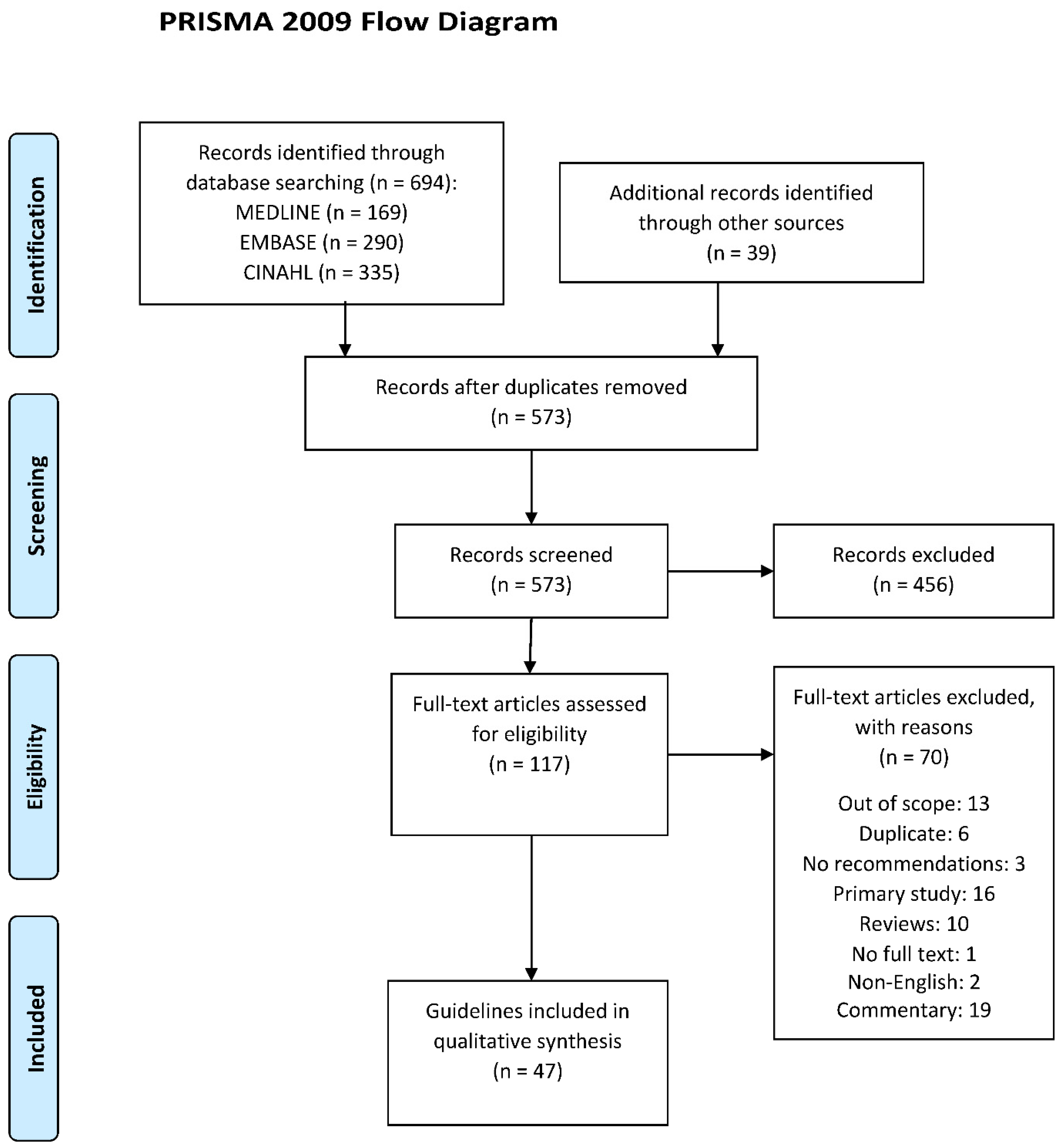

3.1. Results of Search

3.2. Characteristics of Guidelines

3.3. Recommendations on Vitamin D and Calcium

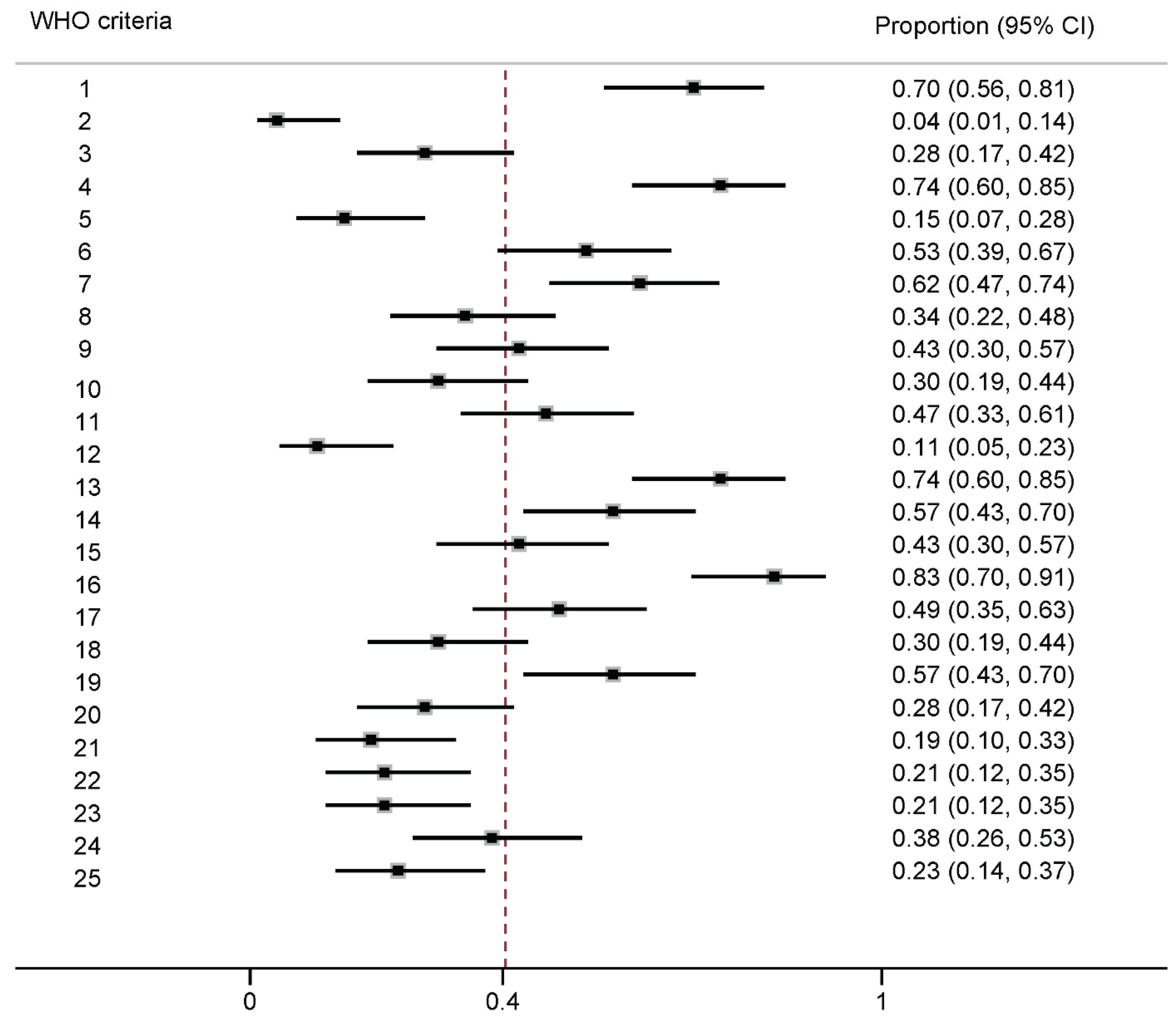

3.4. Assessment of Guideline Methods

3.5. Evidence Cited to Support Recommendations

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. 2014. Available online: https://www.iofbonehealth.org/news/why-seniors-are-more-vulnerable-calcium-and-vitamin-d-deficiency (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Papadimitriou, N.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Orfanos, P.; Benetou, V.; Ntzani, E.E.; Soerjomataram, I.; Künn-Nelen, A.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Eriksson, S.; Brenner, H.; et al. Burden of hip fracture using disability-adjusted life-years: A pooled analysis of prospective cohorts in the CHANCES consortium. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e239–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katsoulis, M.; Benetou, V.; Karapetyan, T.; Feskanich, D.; Grodstein, F.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Eriksson, S.; Wilsgaard, T.; Jørgensen, L.; Ahmed, L.A.; et al. Excess mortality after hip fracture in elderly persons from Europe and the USA: The CHANCES project. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 281, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, C.; Kelly, M.; Quinlan, J.F. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—A systematic review. World J. Orthop. 2019, 10, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Veldurthy, V.; Patel, N.; Wei, R. Intestinal Regulation of Calcium: Vitamin D and Bone Physiology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1033, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietschmann, P.; Rauner, M.; Sipos, W.; Kerschan-Schindl, K. Osteoporosis: An age-related and gender-specific disease—A mini-review. Gerontology 2009, 55, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boling, E.P. Gender and osteoporosis: Similarities and sex-specific differences. J. Gend. Specif. Med. 2001, 4, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osterhoff, G.; Morgan, E.F.; Shefelbine, S.J.; Karim, L.; McNamara, L.M.; Augat, P. Bone mechanical properties and changes with osteoporosis. Injury 2016, 47 (Suppl. 2), S11–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wardlaw, G.M. Putting body weight and osteoporosis into perspective. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 63 (Suppl. 3), 433S–436S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J. Controversies in medicine: The role of calcium and vitamin D supplements in adults. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoratou, E.; Tzoulaki, I.; Zgaga, L.; Ioannidis, J.P. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: Umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ 2014, 348, g2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Avenell, A. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, P.; Bennett, D.; Mafham, M.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Armitage, J.; Clarke, R. Vitamin D and Calcium for the Prevention of Fracture: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1917789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2014, 383, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahwati, L.C.; Weber, R.P.; Pan, H.; Gourlay, M.; LeBlanc, E.; Coker-Schwimmer, M.; Viswanathan, M.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Vitamin D, Calcium, or Combined Supplementation for the Primary Prevention of Fractures in Community-Dwelling Adults: An Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018, 319, 1600–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; Krist, A.H.; et al. Vitamin D, Calcium, or Combined Supplementation for the Primary Prevention of Fractures in Community-Dwelling Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Orav, E.J.; Staehelin, H.B.; Meyer, O.W.; Theiler, R.; Dick, W.; Willett, W.C.; Egli, A. Monthly High-Dose Vitamin D Treatment for the Prevention of Functional Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspray, T.J.; Chadwick, T.; Francis, R.M.; McColl, E.; Stamp, E.; Prentice, A.; von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, A.; Schoenmakers, I. Randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in older people to optimize bone health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Avenell, A.; Gamble, G.D.; Reid, I.R. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: Reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011, 342, d2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Handbook for Guideline Development, 2nd ed.; WHO Library, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual—Process and Methods; 2014; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/resources/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual-pdf-72286708700869 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). 2016 NHMRC Standards for Guidelines; Department of Health, The Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Dai, Z.; Kroeger, C.M.; McDonald, S.; Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Raubenheimer, D.; Bero, L. Methodological quality of public health guideline recommendations on vitamin D and calcium: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Francucci, C.M.; Ceccoli, L.; Caudarella, R.; Rilli, S.; Boscaro, M. Skeletal effect of natural early menopause. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2010, 33 (Suppl. 7), 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shuster, L.T.; Rhodes, D.J.; Gostout, B.S.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A. Premature menopause or early menopause: Long-term health consequences. Maturitas 2010, 65, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicne. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Ross, A.C., Taylor, C.L., Yaktine, A.L., Del Valle, H.B., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oria, M.P.; Kumanyika, S.; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board. Committee on the Development of Guiding Principles for the Inclusion of Chronic Disease Endpoints in Future Dietary Reference Intakes. In Guiding Principles for Developing Dietary Reference Intakes Based on Chronic Disease—The Current Process to Establish Dietary Reference Intakes; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Australian Government Department of Health. Methodological Framework for the Review of Nutrient Reference Values; ACT: Canberra, Australia, 2017; p. 64.

- Woolf, S.; Schunemann, H.J.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Shekelle, P. Developing clinical practice guidelines: Types of evidence and outcomes; values and economics, synthesis, grading, and presentation and deriving recommendations. Implement Sci. 2012, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brouwers, M.; Kho, M.E.; Browman, G.P.; Cluzeau, F.; feder, G.; Fervers, B.; Hanna, S.; Makarski, J. On behalf of the AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can. Med. Assoc. J. Dec. 2010, 182, E839–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stata Corp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaga, V.; Arbyn, M.; Aert, M. “METAPROP: Stata Module to Perform Fixed and Random Effects Meta-Analysis of Proportions”, Statistical Software Components S457781; Boston College Department of Economics: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; revised 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups; 2020; Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Vitamin D and Health; 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/scientific-advisory-committee-on-nutrition; (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Barba, C.V.C.; Cabrera, M.I.C. Recommended energy and nutrient intakes for Filipinos 2002. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 7, 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Government Dietary Recommendations; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016; p. 12.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand Including Recommended Dietary Intakes. A Joint Initiative of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the New Zealand Ministry of Health; ACT: Canberra, Australia, 2005.

- World Health Organization. Definition of Regional Groupings. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/definition_regions/en/#:~:text=Health%20Statistics%20(RGHS)-,Definition%20of%20regional%20groupings,Region%2C%20and%20Western%20Pacific%20Region (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- World Health Organization; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Outcome of a public consultation on the Draft Scientific Opinion of the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA) on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin D. EFSA Support. Publ. 2016, 13, EN-1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for calcium. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avenell, A.; Mak, J.C.; O’Connell, D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, Cd000227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.G.; Zeng, X.T.; Wang, J.; Liu, L. Association Between Calcium or Vitamin D Supplementation and Fracture Incidence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2017, 318, 2466–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, L.A.; Billington, E.O.; Rose, M.S.; Raymond, D.A.; Hanley, D.A.; Boyd, S.K. Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation on Volumetric Bone Density and Bone Strength: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, V.; Leung, W.; Grey, A.; Reid, I.R.; Bolland, M.J. Calcium intake and bone mineral density: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 351, h4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Reports of the Surgeon General. Edtion ed. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General; Office of the Surgeon General: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004.

- Boyd, E.A.; Bero, L.A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 4. Managing conflicts of interests. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2006, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyd, E.A.; Lipton, S.; Bero, L.A. Implementation of financial disclosure policies to manage conflicts of interest. Health Aff. 2004, 23, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Australian Governemnt National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines for Guidelines: Identifying and Managing Conflicts of Interest; 2018. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/plan/identifying-and-managing-conflicts-interest (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Blake, P.; Durao, S.; Naude, C.E.; Bero, L. An analysis of methods used to synthesize evidence and grade recommendations in food-based dietary guidelines. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehfuess, E.A.; Stratil, J.M.; Scheel, I.B.; Portela, A.; Norris, S.L.; Baltussen, R. The WHO-INTEGRATE evidence to decision framework version 1.0: Integrating WHO norms and values and a complexity perspective. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. 1), e000844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics of Guidelines | Recommendations on Vitamin D and Calcium | Evidence Cited to Support Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Title; Guideline developing authority or organization; Publication year; Age group; Sex of target population; Funding source | Daily intake of vitamin D (IU/day); Dietary intake of vitamin D rich foods; Dosage of vitamin D supplements (IU/day); Daily intake of calcium (mg/day); Dietary intake of calcium rich foods; Dosage of calcium supplements (mg/day); Sunlight exposure; Recommended level of serum 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | Verbatim text that referenced the supporting studies/guidelines; Full-text articles of supporting studies grouped to the following types (previous guidelines from other countries): International guidelines (e.g., guidelines published from the World Health Organization; Systematic review of RCTs; Systematic review of non-randomized studies; Clinical trial; Cohort study; Cross-sectional study; Case-control study; Other (such as narrative review, editorial, and commentary) |

| Characteristics | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | ||

| 2009–2014 | 31 | 65 |

| 2015–2019 | 16 | 35 |

| Age distribution | ||

| ≥40 years | 13 | 27 |

| ≥50 years | 22 | 47 |

| ≥60 years | 6 | 13 |

| Adults in general (≥18 years) | 6 | 13 |

| Sex distribution | ||

| Women | 12 | 26 |

| Men | 1 | 2 |

| Both sexes | 34 | 72 |

| WHO regions 1 | ||

| Africa | 1 | 2 |

| Americas | 13 | 28 |

| South-East Asia | 2 | 4 |

| Europe | 16 | 34 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 1 | 2 |

| Western Pacific | 12 | 26 |

| Other (international guidelines) | 2 | 4 |

| Guideline organization category | ||

| Medical or academic society | 42 | 89 |

| Government body | 5 | 11 |

| Funding source | ||

| None disclosed | 29 | 62 |

| Government agency | 8 | 17 |

| Medical society | 5 | 11 |

| Pharmaceutical/Food Industry | 4 | 9 |

| Mixed sources | 1 | 2 |

| Recommendations | Counts | Percentage of Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | ||

| Recommended daily intake (IU/d) | 37 | 79% |

| 200–600 | 1 | 3% |

| 400–800 | 3 | 8% |

| 400–800; 800–1000 1 | 1 | 3% |

| 400 | 3 | 8% |

| 800 | 6 | 16% |

| 600; 800 1 | 1 | 3% |

| 600–800 | 4 | 11% |

| 800–1000 | 8 | 22% |

| 800–2000 | 4 | 11% |

| >800 | 2 | 5% |

| 1000 | 1 | 3% |

| 1000–2000 | 1 | 3% |

| 1500–2000 | 1 | 3% |

| 4000 | 1 | 3% |

| Recommendation on dietary vitamin D | 19 | 40% |

| Recommendation on supplemental vitamin D | 45 | 96% |

| Recommendation on sunlight exposure | 12 | 26% |

| Recommended level of serum 25(OH)D concentration (nmol/L) | 33 | 70% |

| >25 | 1 | 2% |

| 50 | 3 | 6% |

| 75 | 9 | 19% |

| 80 | 1 | 2% |

| ≥70 | 1 | 2% |

| ≥75 | 3 | 6% |

| >50 | 1 | 2% |

| >60 | 1 | 2% |

| 50–125; 75–200 1 | 1 | 2% |

| 50–75 | 4 | 9% |

| 50–80 | 1 | 2% |

| 68–75 | 1 | 2% |

| 75–125 | 4 | 9% |

| 75–150 | 1 | 2% |

| 75–250 | 1 | 2% |

| Calcium | ||

| Recommended daily intake (mg/d) | 35 | 74% |

| 600 | 1 | 3% |

| 750 | 1 | 3% |

| 700; 800 1 | 1 | 3% |

| 700–1200 | 2 | 6% |

| 800–1000 | 2 | 6% |

| 800–1200 | 1 | 3% |

| 1000 | 4 | 11% |

| 1200 | 14 | 40% |

| 1000; 1200 1 | 3 | 9% |

| 1000; 1300 1 | 1 | 3% |

| 1000–1200 | 5 | 14% |

| Recommendation on dietary calcium | 34 | 72% |

| Recommendation on supplemental calcium | 38 | 81% |

| For both nutrients | ||

| Recommendation on a whole foods diet to maintain bone health | 8 | 17% |

| WHO Guideline Development Criteria | Recommendation Made for Daily Intake of Vitamin D | Recommendation Made for Daily Intake of Calcium | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD (99% CI) | p-Value | RD (99% CI) | p-Value | |

| 1. Discipline representation | −0.16 (−0.48, 0.16) | 0.30 | 0.04 (−0.32, 0.41) | 0.73 |

| 2. Diversity representation | −0.26 (−1.18, 0.67) | 0.45 | −0.26 (−1.18, 0.67) | 0.45 |

| 3. Stakeholder input | −0.15 (−0.52, 0.23) | 0.47 | −0.04 (−0.41, 0.32) | 0.73 |

| 4. COI disclosure | −0.01 (−0.38, 0.37) | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.46, 0.22) | 0.70 |

| 5. COI managed | −0.04 (−0.51, 0.44) | 1.00 | 0.13 (−0.25, 0.52) | 0.66 |

| 6. Funder disclosure | 0.03 (−0.3, 0.36) | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.3, 0.36) | 1.00 |

| 7. PICO format of research question | −0.03 (−0.37, 0.31) | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.29, 0.41) | 0.73 |

| 8. Priority outcomes | 0.03 (−0.31, 0.37) | 1.00 | 0.03 (−0.31, 0.37) | 1.00 |

| 9. Systematic search | 0.18 (−0.13, 0.49) | 0.19 | 0.18 (−0.13, 0.49) | 0.19 |

| 10. Systematic review methods to retrieve evidence | 0.06 (−0.29, 0.4) | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.29, 0.4) | 1.00 |

| 11. Evidence quality assessment | −0.03 (−0.36, 0.3) | 1.00 | −0.12 (−0.45, 0.21) | 0.51 |

| 12. Systematic review methods to synthesize evidence | 0.06 (−0.43, 0.55) | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.43, 0.55) | 1.00 |

| 13. Recommendations linked to evidence | −0.1 (−0.46, 0.25) | 0.70 | −0.1 (−0.46, 0.25) | 0.70 |

| 14. Consensus process | −0.01 (−0.34, 0.32) | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.26, 0.41) | 0.74 |

| 15. Method employed to determine strength and certainty of recommendations | 0.01 (−0.32, 0.34) | 1.00 | 0.01 (−0.32, 0.34) | 1.00 |

| 16. Priority of problem of the disease | 0.29 (−0.19, 0.78) | 0.18 | −0.01 (−0.44, 0.43) | 1.00 |

| 17. Quality of evidence | 0.07 (−0.25, 0.4) | 0.74 | −0.01 (−0.34, 0.32) | 1.00 |

| 18. Certainty of evidence | 0.06 (−0.29, 0.4) | 1.00 | 0.06 (−0.29, 0.4) | 1.00 |

| 19. Benefits and harms of recommendation | −0.25 (−0.55, 0.04) | 0.09 | 0.01 (−0.32, 0.35) | 1.00 |

| 20. Balance of desirable and undesirable effects of recommendations | −0.04 (−0.41, 0.32) | 0.73 | −0.04 (−0.41, 0.32) | 0.73 |

| 21. Outcome importance of disease | 0.07 (−0.31, 0.45) | 1.00 | 0.2 (−0.11, 0.51) | 0.41 |

| 22. Health equity | −0.02 (−0.42, 0.37) | 1.00 | 0.1 (−0.26, 0.45) | 0.70 |

| 23. Acceptability | −0.38 (−0.8, −0.04) | 0.02 | −0.14 (−0.56, 0.27) | 0.44 |

| 24. Feasibility | −0.01 (−0.35, 0.32) | 1.0 | −0.01 (−0.35, 0.32) | 1.00 |

| 25. External review of guideline/recommendations | 0.1 (−0.25, 0.46) | 0.70 | 0.34 (0.14, 0.55) | 0.04 |

| Recommendations | Types of Evidence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Guidelines Citing Evidence 1 | Any Type of Previous Guideline 2 | Source Country of Guideline 2 | Previous Guideline from Other Countries2 | WHO/FAO Guideline 2 | Systematic Review of RCTs 2 | Systematic Review of non-RCTs 2 | Clinical Trial 2 | Cohort Study 2 | Cross-Sectional Study 2 | Case-Control Study 2 | Other 2 (Narrative Review, Editorial, Commentary) | |

| Vitamin D recommendations | ||||||||||||

| Recommended daily intake | 37 (79) | 18 (49) | 10 (27) | 9 (24) | 5 (14) | 11 (30) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dietary intake | 19 (40) | 7 (37) | 3 (16) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Supplemental intake | 45 (96) | 21 (47) | 12 (27) | 10 (22) | 4 (9) | 19 (42) | 2 (4) | 14 (31) | 3 (7) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 6 (13) |

| Serum vitamin D level | 33 (70) | 20 (61) | 10 (30) | 12 (36) | 6 (18) | 11 (33) | 4 (12) | 3 (9) | 5 (15) | 7 (21) | 0 (0) | 5 (15) |

| Sunlight exposure | 12 (26) | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (33) |

| Calcium recommendations | ||||||||||||

| Recommended daily intake | 35 (74) | 17 (49) | 10 (29) | 6 (17) | 2 (6) | 10 (29) | 0 (0) | 8 (23) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) |

| Dietary intake | 34 (72) | 14 (41) | 11 (32) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | 7 (21) | 1 (3) | 4 (12) | 4 (12) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| Supplemental intake | 38 (81) | 8 (21) | 6 (16) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 15 (41) | 0 (0) | 7 (19) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, Z.; McKenzie, J.E.; McDonald, S.; Baram, L.; Page, M.J.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Raubenheimer, D.; Bero, L.A. Assessment of the Methods Used to Develop Vitamin D and Calcium Recommendations—A Systematic Review of Bone Health Guidelines. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2423. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072423

Dai Z, McKenzie JE, McDonald S, Baram L, Page MJ, Allman-Farinelli M, Raubenheimer D, Bero LA. Assessment of the Methods Used to Develop Vitamin D and Calcium Recommendations—A Systematic Review of Bone Health Guidelines. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2423. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072423

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Zhaoli, Joanne E. McKenzie, Sally McDonald, Liora Baram, Matthew J. Page, Margaret Allman-Farinelli, David Raubenheimer, and Lisa A. Bero. 2021. "Assessment of the Methods Used to Develop Vitamin D and Calcium Recommendations—A Systematic Review of Bone Health Guidelines" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2423. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072423