Artificial Intelligence-Based Evaluation of Post-Procedural Electrocardiographic Parameters to Identify Patients at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Transcatheter Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Procedural Workflow

2.2. AI Analysis

2.2.1. Image Preparation and Calibration

- ECG digitization;

- image upscaling;

- grid-based pixel-to-unit calibration;

- deterministic AI-based waveform measurement;

- quality-control validation against manual measurements.

2.2.2. AI ECG Measurement Pipeline

- time (ms) at 25 mm/s;

- amplitude (mV) at 10 mm/mV.

- P-wave onset: first deviation from the isoelectric line preceding the QRS;

- P-wave offset: return to the isoelectric line before the PQ junction;

- QRS complex: maximal-slope depolarization, used as temporal reference;

- T wave: post-QRS repolarization, excluded via a pre-QRS search window.

- QRS complex detection using slope- and energy-based criteria;

- Opening of a 250 ms backward search window to locate the P wave;

- Baseline estimation via the median of a 120–160 ms low-slope segment;

- Identification of P-wave onset and offset based on baseline crossings.

- P-wave duration: onset-to-offset interval (ms);

- P-wave amplitude: maximal absolute deviation from the baseline (mV).

- mean P-wave amplitude;

- maximum P-wave amplitude;

- P-wave dispersion (max–min duration across limb, precordial and all leads);

- P-wave Vector Magnitude (PwVM):

2.2.3. Quality Control and Validation

2.3. Classification of Arrhythmic Recurrence

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Data Privacy and Ethical Handling of ECG Images

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CA | Catheter Ablation |

| CIED | Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device |

| CMR | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance |

| COU | Complex Operative Unit |

| CS | Coronary sinus |

| DOAC | Direct Oral Anticoagulant |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ILR | Implantable Loop Recorder |

| LA | Left Atrium |

| MI | Mitral Isthmus |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PN | Phrenic Nerve |

| PVI | Pulmonary Vein Isolation |

| PwA | P-wave Amplitude |

| PwVM | P-wave Vector Magnitude |

| RF | Radiofrequency |

| SR | Sinus Rhythm |

| TCA | Transcatheter Ablation |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

References

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Corleto, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Anselmino, M.; Ferraris, F.; Di Biase, L.; Natale, A.; Hunter, R.J.; Schilling, R.J.; Miyazaki, S.; et al. Which Are the Most Reliable Predictors of Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Transcatheter Ablation?: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 1984–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intzes, S.; Zagoridis, K.; Symeonidou, M.; Spanoudakis, E.; Arya, A.; Dinov, B.; Dagres, N.; Hindricks, G.; Bollmann, A.; Kanoupakis, E.; et al. P-Wave Duration and Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Catheter Ablation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Europace 2023, 25, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.H.; Ribeiro, M.H.; Paixão, G.M.M. Automatic Diagnosis of the 12-Lead ECG Using a Deep Neural Network. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strodthoff, N.; Wagner, P.; Schaeffter, T.; Samek, W. Deep Learning for ECG Analysis: Benchmarks and Insights from PTB-XL. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.; Strodthoff, N.; Bousseljot, R.D. PTB-XL, a Large Publicly Available Electrocardiography Dataset. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tison, G.H.; Zhang, J.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.C. Automated and Interpretable Patient ECG Profiles for Disease Detection, Tracking, and Discovery. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, Z.I. An Artificial Intelligence-Enabled ECG Algorithm for the Identification of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation during Sinus Rhythm: A Retrospective Analysis of Outcome Prediction. Lancet 2019, 394, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabile, G.; Bertaglia, E.; Senatore, G.; De Simone, A.; Zoppo, F.; Donnici, G.; Turco, P.; Pascotto, P.; Fazzari, M.; Vitale, D.F. Catheter Ablation Treatment in Patients with Drug-Refractory Atrial Fibrillation: A Prospective, Multi-Centre, Randomized, Controlled Study (Catheter Ablation for The Cure of Atrial Fibrillation Study). Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.D.; Jaïs, P.; Hocini, M.; Sacher, F.; Klein, G.J.; Clémenty, J.; Haïssaguerre, M. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2007, 116, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.R.; Khan, S.; Sheikh, M.A.; Khuder, S.; Grubb, B.; Moukarbel, G.V. Catheter Ablation and Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy as First- or Second-Line Therapy in the Management of Atrial Fibrillation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2014, 7, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, D.L.; Mark, D.B.; Robb, R.A.; Monahan, K.H.; Bahnson, T.D.; Moretz, K.; Poole, J.E.; Mascette, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Jeffries, N.; et al. Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation (CABANA) Trial: Study Rationale and Design. Am. Heart J. 2018, 199, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haïssaguerre, M.; Jaïs, P.; Shah, D.C.; Takahashi, A.; Hocini, M.; Quiniou, G.; Garrigue, S.; Mouroux, A.L.; Métayer, P.L.; Clémenty, J. Spontaneous Initiation of Atrial Fibrillation by Ectopic Beats Originating in the Pulmonary Veins. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Betts, T.R. Approaches to Catheter Ablation for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lv, T.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, P. Use of P Wave Indices to Evaluate Efficacy of Catheter Ablation and Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2022, 65, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-K.; Park, J.; Uhm, J.-S.; Joung, B.; Lee, M.-H.; Pak, H.-N. Low P-Wave Amplitude (<0.1 mV) in Lead I Is Associ-ated with Displaced Inter-Atrial Conduction and Clinical Recurrence of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation after Radiofre-quency Catheter Ablation. Europace 2016, 18, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Feng, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, B.; Fang, Q.; Chen, T.; Yang, C. A Deep Learning-Based Multimodal Fusion Model for Recurrence Prediction in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 1785–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, A.; Zito, E.; Pierucci, N.; Matteucci, A.; La Fazia, V.M. A Talk with ChatGPT: The Role of Artificial Intelli-gence in Shaping the Future of Cardiology and Electrophysiology. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Platonov, P.G.; Cygankiewicz, I.; Soliman, E.Z.; Gorenek, B.; Ikeda, T.; Vassilikos, V.P.; Steinberg, J.S.; Varma, N.; et al. P Wave Parameters and Indices: A Critical Appraisal of Clinical Utility, Challenges, and Future Research-A Consensus Document Endorsed by the International Society of Electrocardiology and the Interna-tional Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e010435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatani, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Tsujino, Y.; Kataoka, N.; Kinugawa, K. P-Wave Vector Magnitude Predicts Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation in Patients with Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019, 24, e12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Y.; Tang, A. Novel P Wave Indices to Predict Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 2616–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cheng, Z.; Deng, H.; Cheng, K.; Chen, T.; Gao, P.; Yu, M.; Fang, Q. The Amplitude of Fibrillatory Waves on Leads aVF and V1 Predicting the Recurrence of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Underwent Catheter Ablation. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013, 18, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yang, X.; Jia, M.; Wang, D.; Cui, X.; Bai, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J. Effectiveness of P-Wave ECG Index and Left Atrial Appendage Volume in Predicting Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after First Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagliani, G.; Leonelli, F.; Padeletti, L. P Wave and the Substrates of Arrhythmias Originating in the Atria. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2017, 9, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonelli, F.; Bagliani, G.; Boriani, G.; Padeletti, L. Arrhythmias Originating in the Atria. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2017, 9, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luik, A.; Schmidt, K.; Haas, A.; Unger, L.; Tzamalis, P.; Brüggenjürgen, B. Ablation of Left Atrial Tachycardia Following Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: 12-Month Success Rates. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.J.; Zhao, J.; Fedorov, V.V. Fibrosis and Atrial Fibrillation: Computerized and Optical Mapping; A View into the Human Atria at Submillimeter Resolution. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2017, 3, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, C.; Luongo, G.; Azzolin, L.; Jadidi, A.; Loewe, A. Non-Invasive and Quantitative Estimation of Left Atrial Fibrosis Based on P Waves of the 12-Lead ECG: A Large-Scale Computational Study Covering Anatomical Variability. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, R.H. Dispersion of Recovery and Vulnerability to Re-entry in a Model of Human Atrial Tissue with Simulated Diffuse and Focal Patterns of Fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Paroxysmal AF | 36 | 48.6 |

| Persistent AF | 38 | 51.4 |

| Male | 58 | 78.4 |

| Female | 16 | 21.6 |

| Family history of CAD | 10 | 13.5 |

| Dyslipidemia | 31 | 41.9 |

| Current smoker | 11 | 14.9 |

| Hypertension | 46 | 62.2 |

| Diabetes | 12 | 16.2 |

| Diabetes on Insulin | 1 | 1.4 |

| COPD | 5 | 6.8 |

| Sleep apnea | 1 | 1.4 |

| PAD | 2 | 2.7 |

| Previous Stroke or TIA | 6 | 8.1 |

| Previous MI | 5 | 6.8 |

| CKD | 6 | 8.1 |

| Heart failure | 10 | 13.5 |

| Previous PCI | 6 | 8.1 |

| Previous CABG | 2 | 2.7 |

| Dysthyroidism | 9 | 12.2 |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| P-wave duration in V6 | 0.391 | 0.001 |

| PVM | 0.228 | 0.036 |

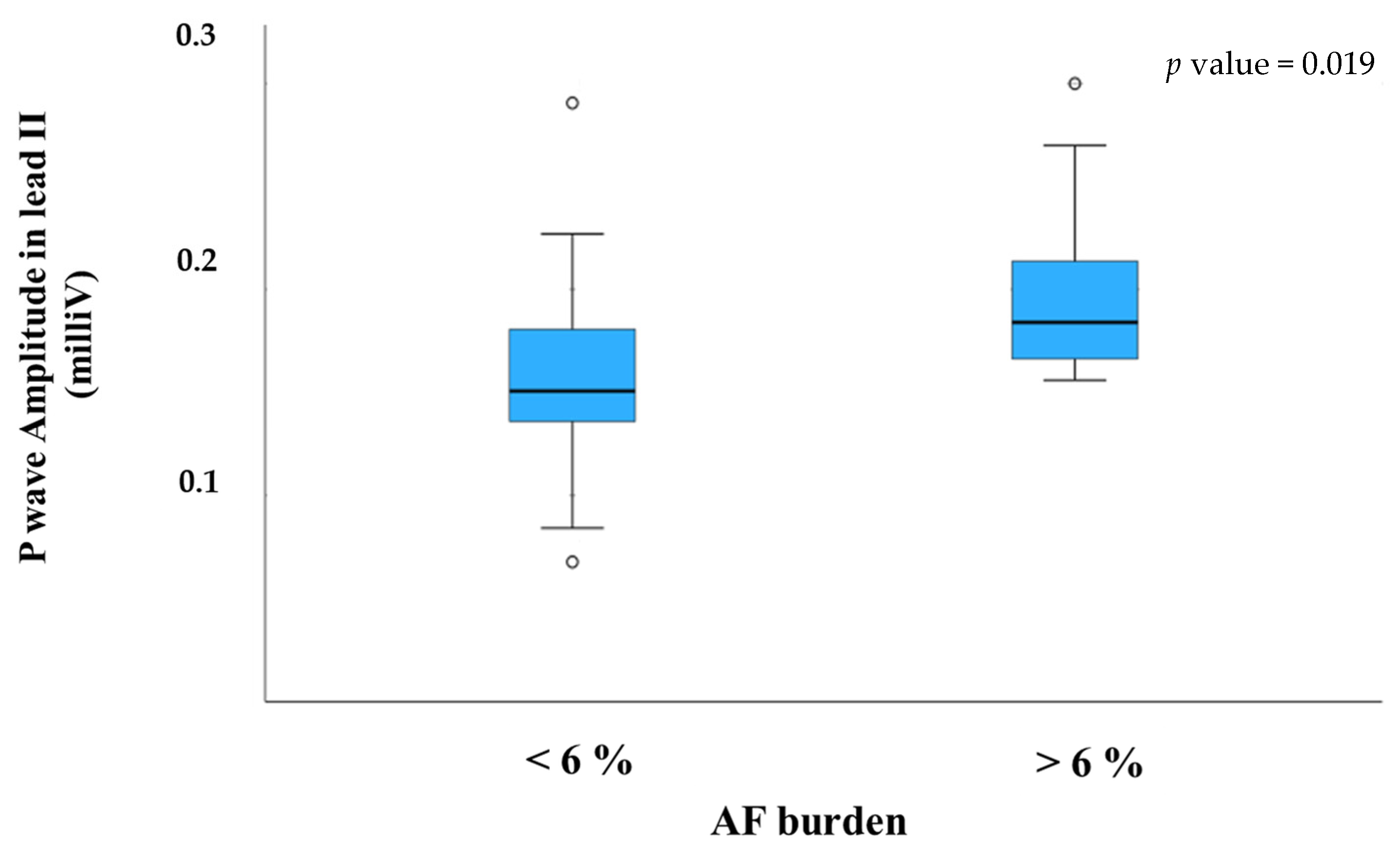

| P-wave amplitude in lead II | 0.389 | 0.002 |

| P-wave amplitude in lead III | 0.256 | 0.027 |

| Mean PWA | 0.308 | 0.010 |

| P-wave duration in lead I | 0.043 | 0.376 |

| P-wave duration in lead III | 0.126 | 0.175 |

| P-wave duration in lead aVR | 0.207 | 0.061 |

| P-wave duration in lead aVL | 0.220 | 0.050 |

| P-wave amplitude in lead I | 0.130 | 0.167 |

| P-wave amplitude in lead aVL | 0.160 | 0.117 |

| P-wave amplitude in lead V1 | 0.188 | 0.081 |

| P-wave amplitude in lead V6 | 0.150 | 0.134 |

| QT dispersion | 0.281 | 0.053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Rosa, G.; Giuggia, M.; Peyracchia, M.; Peddis, M.; Di Summa, R.; Pelissero, E.; Trapani, G.; De Los Rios, D.; Ugliano, F.; Cirillo, P.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Evaluation of Post-Procedural Electrocardiographic Parameters to Identify Patients at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Transcatheter Ablation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228248

De Rosa G, Giuggia M, Peyracchia M, Peddis M, Di Summa R, Pelissero E, Trapani G, De Los Rios D, Ugliano F, Cirillo P, et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Evaluation of Post-Procedural Electrocardiographic Parameters to Identify Patients at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Transcatheter Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228248

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Rosa, Gennaro, Marco Giuggia, Mattia Peyracchia, Martina Peddis, Roberto Di Summa, Elisa Pelissero, Giuseppe Trapani, Davide De Los Rios, Fabio Ugliano, Plinio Cirillo, and et al. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence-Based Evaluation of Post-Procedural Electrocardiographic Parameters to Identify Patients at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Transcatheter Ablation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228248

APA StyleDe Rosa, G., Giuggia, M., Peyracchia, M., Peddis, M., Di Summa, R., Pelissero, E., Trapani, G., De Los Rios, D., Ugliano, F., Cirillo, P., & Senatore, G. (2025). Artificial Intelligence-Based Evaluation of Post-Procedural Electrocardiographic Parameters to Identify Patients at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence After Transcatheter Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8248. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228248