Exploring Hygiene Behaviours Among Child Caregivers in Rural Malawi Using Multilevel Logistic Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Whether there are variations in hygiene behaviours among child caregivers between households in relation to the area of intervention and the non-intervention area;

- Whether there are variations in hygiene behaviours among child caregivers between villages in relation to the area of intervention and the non-intervention area.

1.1. Study Rationale

1.2. The Study’s Conceptual Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population and Setting: Sampling and Data Collection Methods

2.2. Definitions of Key Concepts

- Child caregiver: Any household member, including parents, who are responsible for the daily care of young children.

- Multilevel binary logistic: A type of regression analysis used when the dependent variable is binary, meaning it has two categories. It is commonly used when the outcome is coded as “1” or “0”.

- Behaviour: The performance of a particular action. This includes the execution of both healthy and unhealthy behaviours.

- Hygiene: Conditions and practises that serve to promote or preserve health in the household.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Outcome Variables

- I

- Keeping utensils on an elevated surface;

- II

- Using soap to clean kitchen utensils;

- III

- Washing hands with soap at critical times.

Questions on Targeted Behaviours

2.3.2. Explanatory Variables

Description of Explanatory Variables

2.3.3. Analysis and Estimation

2.3.4. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. The Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Descriptive Estimates of Non-Doers of Washing Hands with Soap at Critical Times, Using Soap to Clean Kitchen Utensils, and Keeping Utensils on a Raised Surface in the Area of Intervention and the Non-Intervention Area at the Household Level

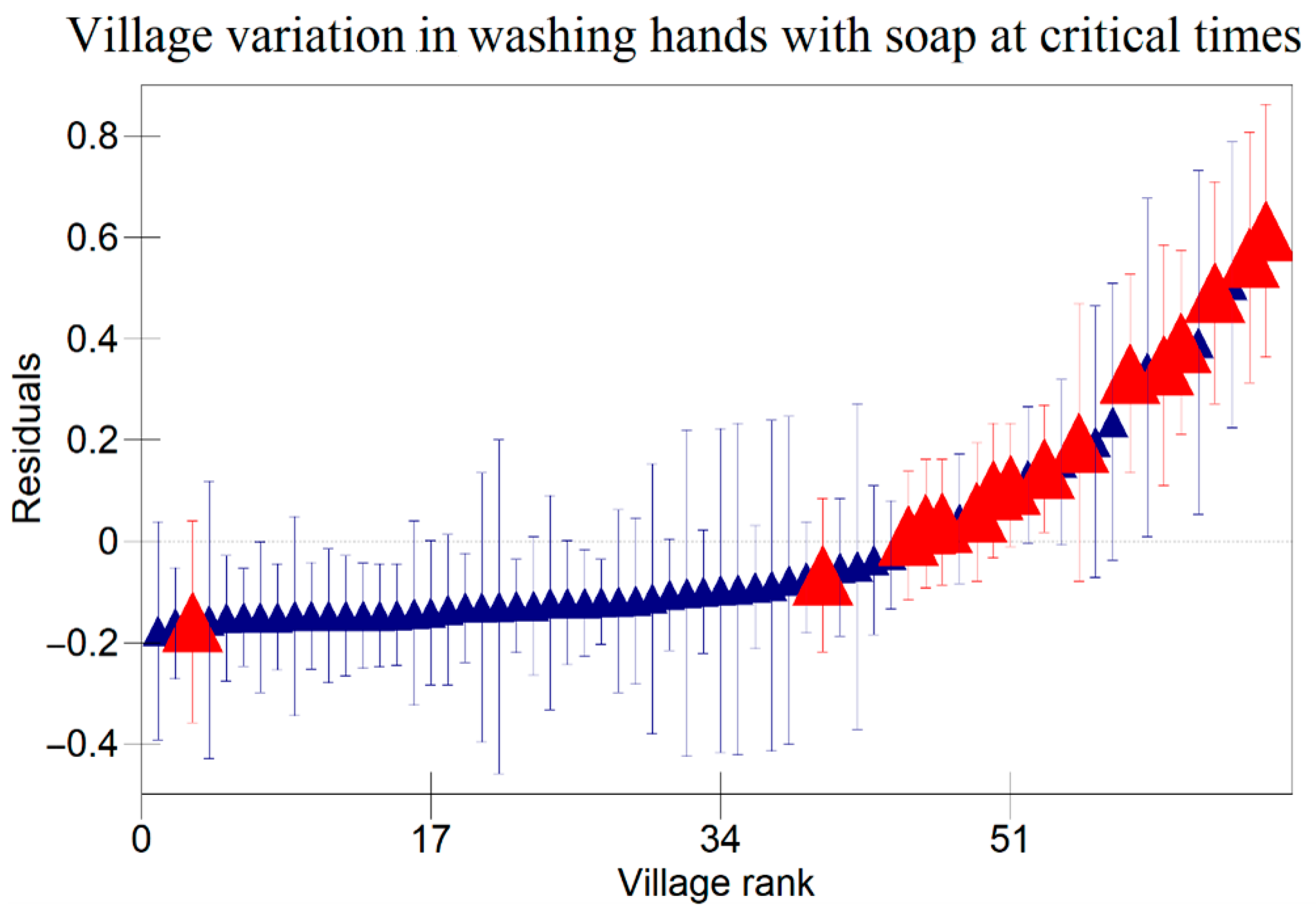

3.3. Variation in Hygiene Behaviours Between Households and Between Villages in Area of Intervention and Non-Intervention Area in Relation to Controlled Risk Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

7. The Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Key Facts About Diarrhoeal Diseases. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Motarjemi, Y.; Steffen, R.; Binder, H. Preventive strategy against infectious diarrhea—A holistic approach. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidziwisano, K.; Slekiene, J.; Mosler, H.J.; Morse, T. Improving complementary food hygiene behaviors using the risk, attitude, norms, ability, and self-regulation approach in rural Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Lanata, C.; Hartinger, S.; Mausezahl, D.; Padilla, B.; Ochoa, T.; Lozada, M.; Pineda, I.; Verastegui, H. Fecal contamination of food, water, hands, and kitchen utensils at the household level in rural areas of Peru. J. Environ. Health 2013, 76, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ehiri, J.; Azubuike, M.; Ubbaonu, C.; Anyanwu, E.; Ibe, K.; Ogbonna, M. Critical control points of complementary food preparation and handling in eastern Nigeria. Bull World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Chidziwisano, K.; Slekiene, J.; Kumwenda, S.; Mosler, H.J.; Morse, T. Toward complementary food hygiene practices among child caregivers in rural Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, V.; Cairncross, S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejemot-Nwadiaro, R.; Ehiri, J.; Arikpo, D.; Meremikwu, M.; Critchley, J. Hand washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD004265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Mosler, H.-J. Determining behavioral factors for interventions to increase safe water consumption: A cross- sectional field study in rural Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2013, 23, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slekiene, J.; Mosler, H. Characterizing the last latrine non- owners in rural Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, E.A.; Ellis, A.; Rodriguez, K.C.; Caruso, B.A.; McClintic, E.E.; Ventura, S.G.; Arriola, K.R.J.; Kowalski, A.J.; Linabarger, M.; Wodnik, B.K.; et al. Determinants of food preparation and hygiene practices among caregivers of children under two in Western Kenya: A formative research study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimli, L.; Lecoutere, E.; Wells, C.R.; Ismayilova, L. More assets, more decision making power? Mediation model in a cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of the graduation program on women’s empowerment in Burkina Faso. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reducing Rural Women’s Domestic Workload Through Labour-Saving Technologies and Practices. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1036784/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Watson, J.; Okumu, N.O.; Wasonga, J.O.; Majiwa, H.; Kiarie, A.; Masudi, S.P.; Ochieng, L.; Alumasa, L.; Mutisya, C.; Cook, E.A.J.; et al. A proof-of-concept randomised controlled trial of an intervention designed to improve food hygiene behaviours among caregivers of young children living in low-income areas of Nairobi, Kenya. PLOS Water 2024, 3, e0000223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutz, G. Hierarchical Models for the Analysis of Likert Scales in Regression and Item Response Analysis. Int. Stat. Rev. 2021, 89, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, R.F.; Palamuleni, M.E. Multilevel analysis of unhealthy bodyweight among women in Malawi: Does urbanisation matter? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e02492289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masangwi, S.J.; Ferguson, N.S.; Grimason, A.M.; Morse, T.D.; Zawdie, G.; Kazembe, L.N. Household and community variations and nested risk factors for diarrhoea prevalence in southern Malawi: A binary logistic multi-level analysis. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2010, 20, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census Preliminary Report; Government of Malawi. 2018. Available online: https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/2018%20Census%20Preliminary%20Report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Chakraborty, N.M.; Fry, K.; Behl, R.; Longfield, K. Simplified asset indices to measure wealth and equity in health programs: A reliability and validity analysis using survey data from 16 countries. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2016, 4, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.D.P.d.; Migon, H.S. Bayesian binary regression model: An application to in-hospital death after ami prediction. Pesquisa Operacional 2004, 24, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Multilevel Statistical Models, 3rd ed.; Arnold: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nkoka, O.; Chuang, T.W.; Chen, Y.H. Multilevel analysis of factors associated with treatment-seeking behaviors among caregivers with febrile children in Malawi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badu, S.Q.; Djafri, N. Effect of leadership village head on empowerment of village potential based on environmental management. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2019, 1. Available online: https://repository.ung.ac.id/karyailmiah/show/3463/syamsu-qamar-badu-jurnal-internasional-effect-of-leadership-village-head-on-empowerment-of-village-potential-based-on-environmental-management.html (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Thieschäfer, L.; Büsch, D. Development and trainability of agility in youth: A systematic scoping review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 952779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangana, A.; Shabila, N.; Heath, T.; White, S. The determinants of handwashing behaviour among internally displaced women in two camps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, V.; Cousens, S.; Mertens, T.; Traore, E.; Kanki, B.; Diallo, I. Structured observations of hygiene behaviours in Burkina Faso: Validity, variability, and utility. Bull World Health Organ. 1993, 71, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Behaviour | Items | Answer format |

|---|---|---|

| Hand washing before eating main meal | Before you feed your child main meals (e.g., lunch), how often do you wash your hands with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Hand washing after using toilet | After you defecate, how often do you wash your hands with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Hand washing before food preparation | Before you prepare food, how often do you wash your hands with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Hand washing before eating snacks | Before you feed your child snacks, how often do you wash your hands with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Hand washing after cleaning child’s bottom | After cleaning child’s bottom, how often do you wash your hands with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Washing kitchen utensils with soap | Before you use kitchen utensils, how often do you wash them with soap and water? | (Almost) at no time–(almost) each time (5-point rating scale) |

| Keeping utensils on an elevated place | Do you keep your kitchen utensils on an elevated place? | Not at all–very much (5-point rating scale) |

| Variable | Description | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Highest education level of child caregiver | Categorical variable: 1 = never been to school, 2 = primary, 3 = secondary and above |

| Age group | Age group of child caregiver | Categorical variable: 1 = 18–28, 2 = 29–38, 3 = 39–48, 4 = 49–58, 5 = over 58 |

| Marital status | Marital status of child caregiver | Binary variable: 0 = single, 1 = married |

| Occupation | Occupation of child caregiver | Categorical variable: 1 = farming, 2 = business, 3 = employed |

| Intervention | Location of child caregiver; whether they were in intervention area or not | Binary variable: 0 = not in intervention, 1 = in intervention |

| Relative wealth | Social-economic status of child caregiver | Categorical variable: 1 = high, 2 = middle, 3 = low |

| Health knowledge | Child caregiver’s knowledge of diarrhoea disease | Binary variable: 0 = not knowledgeable, 1 = knowledgeable |

| Risk | Child caregiver’s understanding of risk factors associated with diarrhoea | Binary variable: 0 = at risk, 1 = not at risk |

| Effort | Whether child caregiver found performing proper hygiene behaviour difficult or easy | Binary variable: 0 = difficult, 1 = easy |

| Norm | Whether child caregiver’s behaviours are results of guidance from local authorities | Binary variable: 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Confidence | Confidence of child caregiver when performing proper hygiene behaviours | Binary variable: 0 = not confident, 1 = confident |

| Willingness | Willingness of child caregiver to perform proper hygiene behaviours | Binary variable: 0 = not willing, 1 = willing |

| Perception of price | Child caregiver’s perception of price of soap used for household sanitation use | Binary variable: 0 = not expensive, 1 = expensive |

| Variable | Description | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Never | 21 |

| Primary | 70 | |

| Secondary and above | 10 | |

| Age group | 18–28 | 59 |

| 29–38 | 29 | |

| 39–48 | 10 | |

| 49–58 | 1 | |

| Over 58 | 1 | |

| Marital status | Single | 9 |

| Married | 91 | |

| Occupation | Farming | 72.9 |

| Business | 14.9 | |

| Employed | 12.1 | |

| Relative Wealth | Low | 86.5 |

| Middle | 10.8 | |

| High | 2.7 |

| Behaviour | Category | Caregivers in Non-Intervention Area (%) | Caregivers in Intervention Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keeping utensils on a raised surface | Keep utensils on a raised surface | 32 | 96 |

| Do not keep utensils on a raised surface | 68 | 4 | |

| Washing hands with soap at critical times | Wash hands with soap | 70 | 97 |

| Do not wash hands with soap | 30 | 3 | |

| Using soap to clean kitchen utensils | Use soap to clean kitchen utensils | 78 | 97 |

| Do not use soap to clean kitchen utensils | 22 | 3 |

| Keep Utensils on a Raised Surface | Use Soap for Cleaning Utensils | Wash Hands with Soap at Critical Times | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Β | t-Value | p-Value | Β | t-Value | p-Value | β | t-Value | p-Value |

| Educational Background | |||||||||

| Never | Reference group | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.013 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 0 | −0.09 | 0.93 | 0.043 | 1.87 | 0.62 |

| Secondary and above | 0.004 | 0.103 | 0.92 | −0.03 | −0.94 | 0.35 | 0.076 | 2.11 | 0.04 ** |

| No | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.019 | 0.358 | 0.72 | −0.03 | −0.56 | 0.58 | 0.062 | 1.29 | 0.2 |

| Age Group | |||||||||

| 18–28 | Reference group | ||||||||

| 29–38 | −0.05 | −2.22 | 0.03 ** | −0.02 | −0.79 | 0.43 | 0.031 | 1.48 | 0.14 |

| 39–48 | −0.01 | −0.29 | 0.77 | 0.011 | 0.367 | 0.71 | −0.009 | −0.28 | 0.78 |

| 49–58 | −0.12 | −1.23 | 0.22 | 0.036 | 0.439 | 0.66 | 0.142 | 1.65 | 0.99 |

| Over 58 | −0.07 | −0.47 | 0.64 | −0.05 | −0.43 | 0.67 | 0.079 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Unmarried | Reference group | ||||||||

| Married | −0.01 | −0.19 | 0.85 | 0.018 | 0.6 | 0.55 | 0.035 | 1.09 | 0.27 |

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Farming | Reference group | ||||||||

| Business | −0.03 | −1.07 | 0.28 | 0.008 | 0.333 | 0.74 | −0.031 | −1.19 | 0.23 |

| Employed | 0.036 | 1.161 | 0.25 | 0.073 | 2.808 | 0.005 ** | −0.075 | −2.68 | 0.008 ** |

| Intervention | |||||||||

| No | Reference group | ||||||||

| Yes | −0.63 | −24 | <0.00001 ** | −0.17 | −7.91 | <0000.1 ** | 0.256 | 11.1 | <0.00001 ** |

| Relative Wealth | |||||||||

| Low | Reference group | ||||||||

| Middle | 0.077 | 1.75 | 0.08 * | −0.01 | −310 | 0.76 | −0.034 | −1.06 | 0.28 |

| High | −0.04 | −0.5 | 0.62 | −0.07 | −1.33 | 0.1 * | 0.086 | 1.43 | 0.1 * |

| Health Knowledge | |||||||||

| Not knowledgeable | Reference group | ||||||||

| Knowledgeable | 0.004 | 0.2 | 0.84 | −0.01 | −0.29 | 0.77 | −0.012 | −0.67 | 0.5 |

| Risk | |||||||||

| Not at risk | Reference group | ||||||||

| At risk | 0.098 | 1.4 | 0.16 | 0.068 | 1.133 | 0.26 | 0.012 | 0.19 | 0.85 |

| Effort | |||||||||

| Difficult | Reference group | ||||||||

| Easy | 0.008 | 0.195 | 0.85 | 0.047 | 1.343 | 0.18 | −0.018 | −0.49 | 0.63 |

| Norm | |||||||||

| No | Reference group | ||||||||

| Yes | 0 | −0.07 | 0.95 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.97 | −0.008 | −0.2 | 0.85 |

| Confidence | |||||||||

| Not confident | Reference group | ||||||||

| Confident | −0.3 | −3.43 | 0.0006 ** | −0.09 | −1.24 | 0.22 | 0.224 | 2.84 | 0.005 ** |

| Willingness | |||||||||

| Not willing | Reference group | ||||||||

| Willing | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.994 | 0.072 | 0.692 | 0.49 | −0.201 | −1.83 | 0.07 * |

| Perception of Price | |||||||||

| Not expensive | Reference group | ||||||||

| Expensive | 0.013 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 0.102 | 4.636 | <0.00001 ** | −0.098 | −0.43 | 0.67 |

| Household Effects | 0.003 | 1.5 | <0.00001 ** | 0.001 | 1 | <0.00001 ** | 0.001 | 1 | <0.00001* * |

| Village Effects | 0.076 | 19 | <0.00001 ** | 0.056 | 18.67 | <0.00001 ** | 0.063 | 21 | <0.00001 ** |

| DIC | 216.59 | −34.13 | 66.71 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anusa, C.; Masangwi, S.J.; Chidziwisano, K.; Morse, T. Exploring Hygiene Behaviours Among Child Caregivers in Rural Malawi Using Multilevel Logistic Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050801

Anusa C, Masangwi SJ, Chidziwisano K, Morse T. Exploring Hygiene Behaviours Among Child Caregivers in Rural Malawi Using Multilevel Logistic Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050801

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnusa, Collins, Salule Joseph Masangwi, Kondwani Chidziwisano, and Tracy Morse. 2025. "Exploring Hygiene Behaviours Among Child Caregivers in Rural Malawi Using Multilevel Logistic Models" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050801

APA StyleAnusa, C., Masangwi, S. J., Chidziwisano, K., & Morse, T. (2025). Exploring Hygiene Behaviours Among Child Caregivers in Rural Malawi Using Multilevel Logistic Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050801