Perceptions of Health Risks and Accessibility: A Social Media-Based Pilot Study of Factors Influencing Use of Vaping and Combustible Tobacco Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

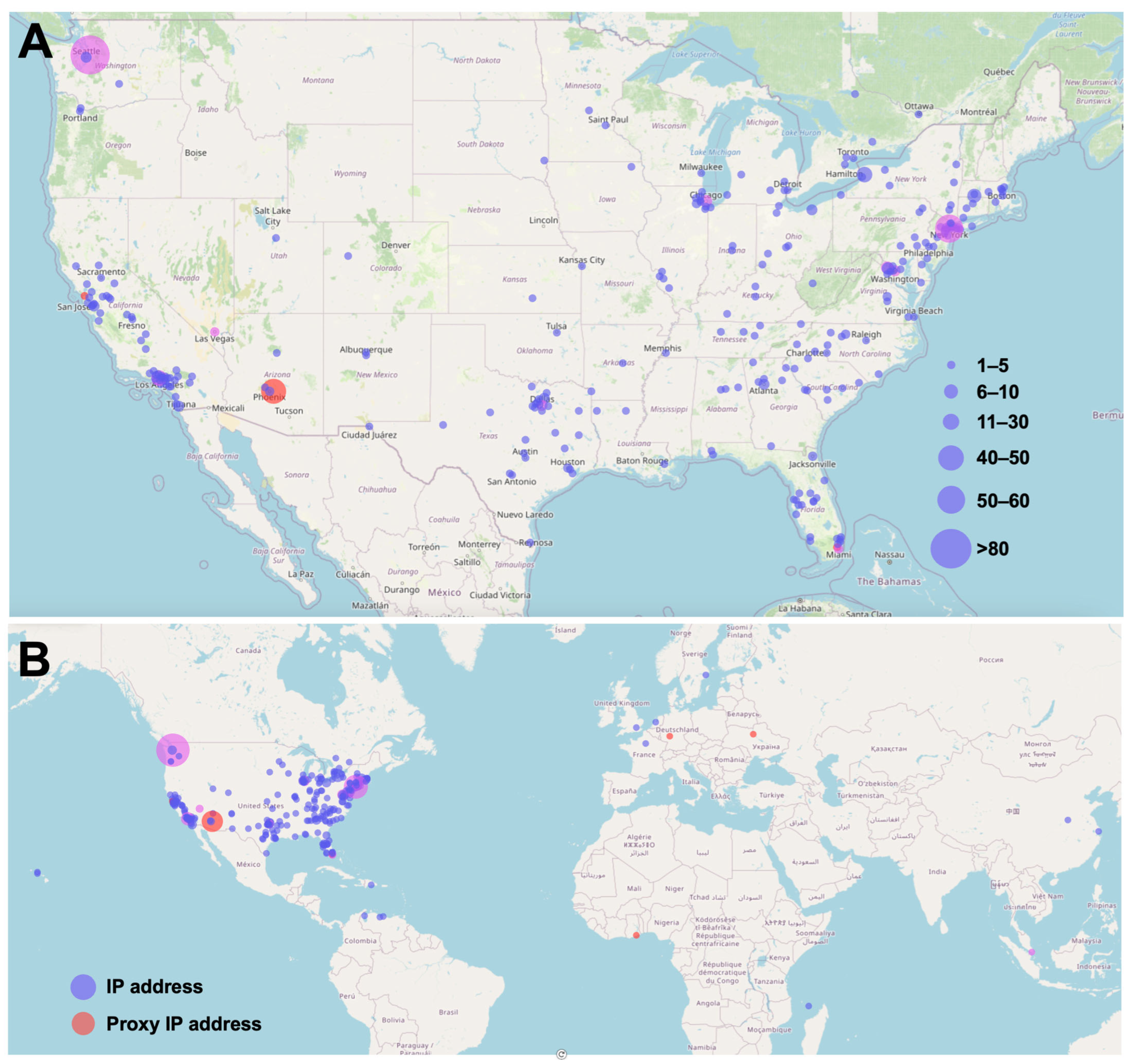

2.1. Survey Design and Distribution

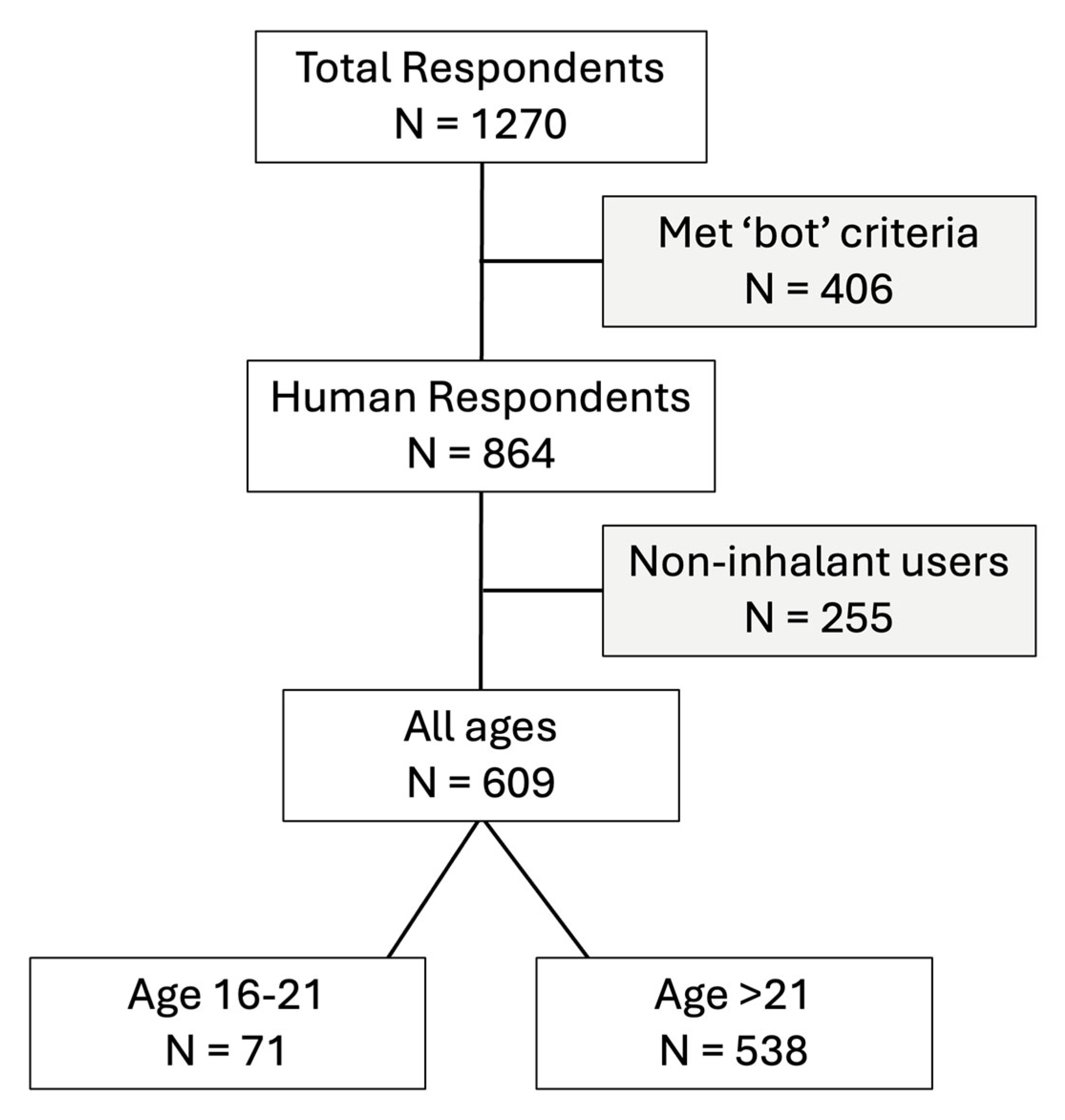

2.2. Assessment for ‘Bots’

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

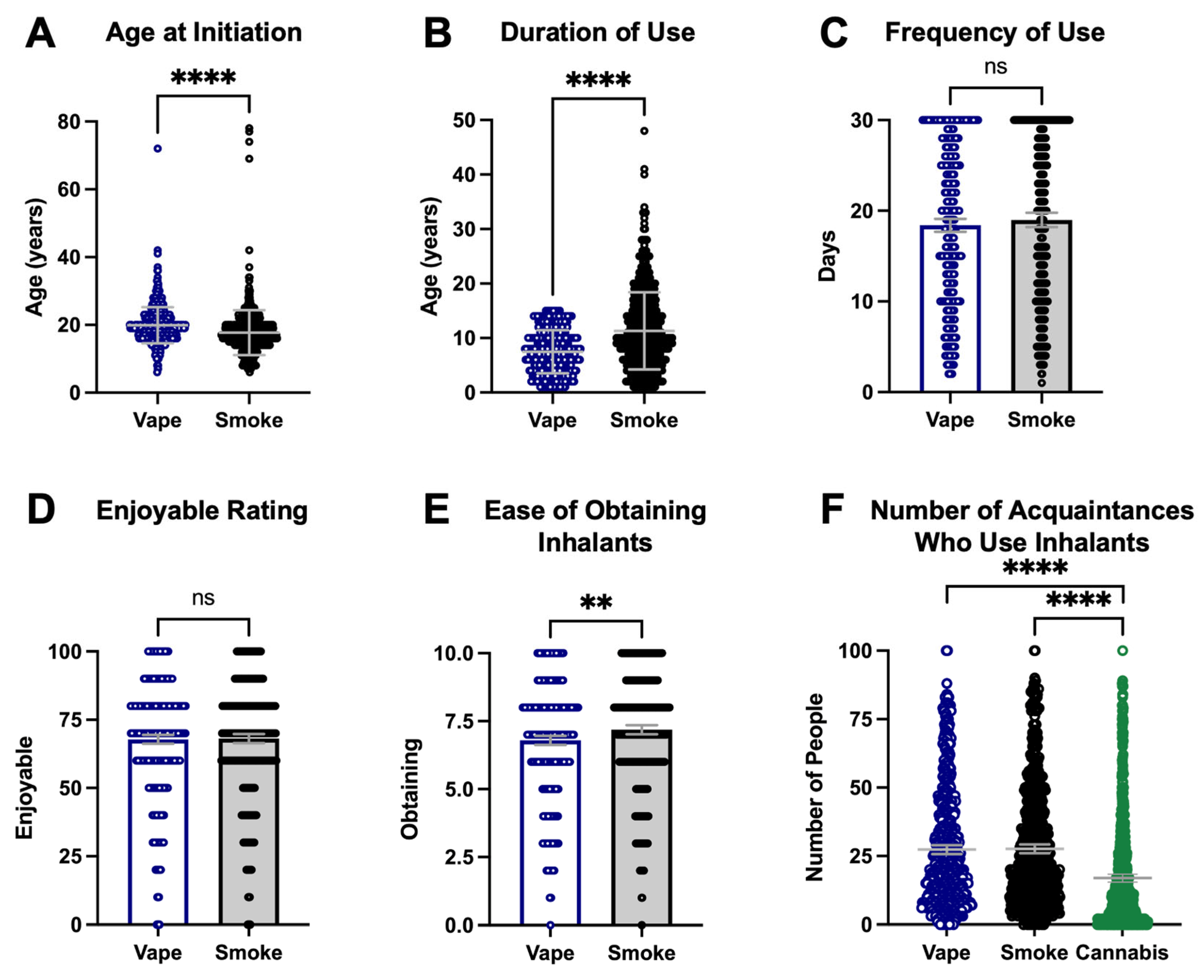

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Survey Respondents

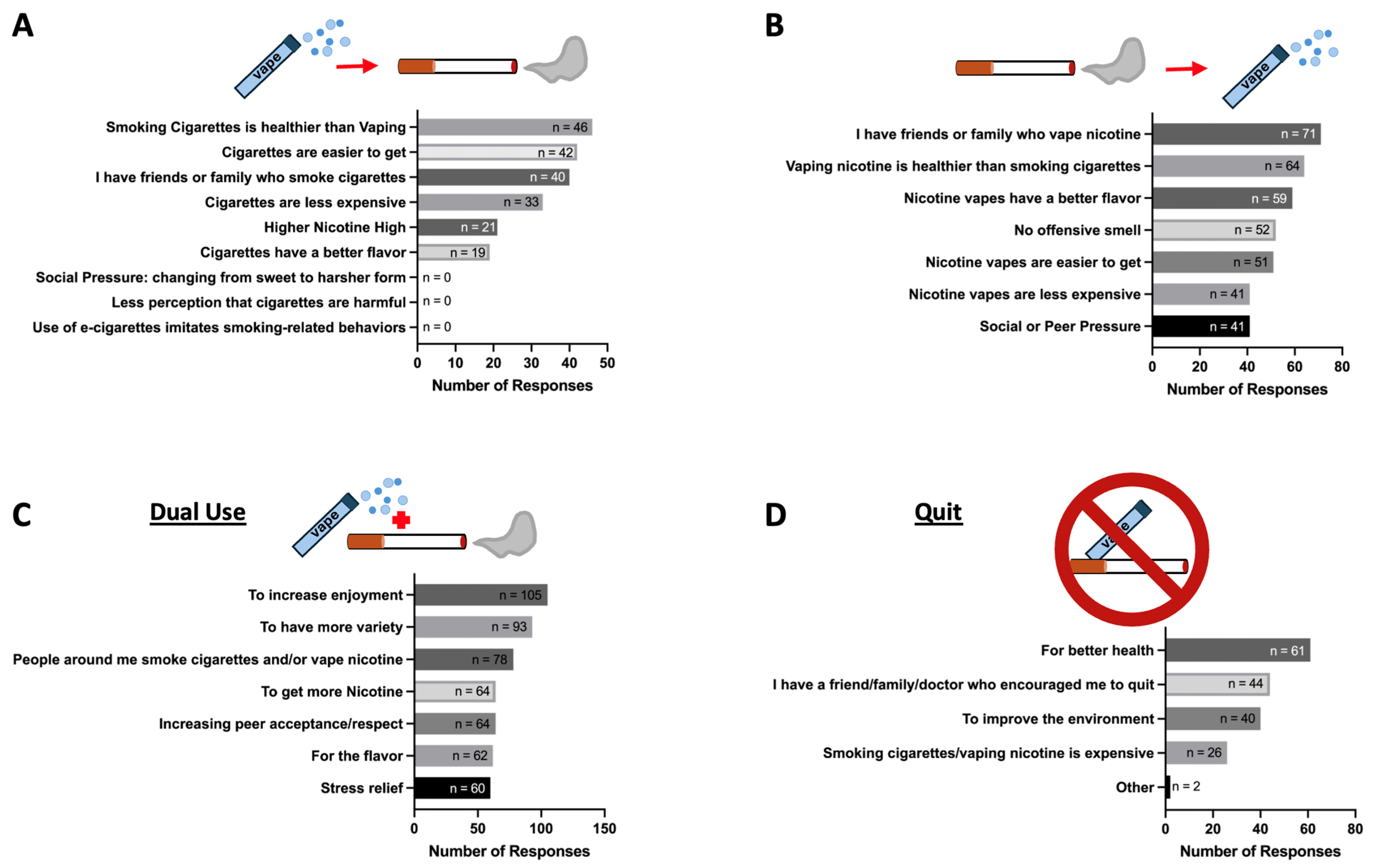

3.2. Factors Contributing to Switching from Vaping Nicotine (Using E-Cigarettes) to Smoking Cigarettes

3.3. Factors Contributing to Switching from Smoking Cigarettes to Vaping Nicotine

3.4. Multi-Inhalant Use of Nicotine Vapes and Combustible Cigarettes

3.5. Quitters of Tobacco Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soneji, S.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Wills, T.A.; Leventhal, A.M.; Unger, J.B.; Gibson, L.A.; Yang, J.; Primack, B.A.; Andrews, J.A.; Miech, R.A.; et al. Association Between Initial Use of e-Cigarettes and Subsequent Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Cao, S.; Gong, W.; Fei, F.; Wang, M. Electronic Cigarettes Use and Intention to Cigarette Smoking among Never-Smoking Adolescents and Young Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, T.; Eckel, S.; Liu, F.; Barrington-Trimis, J.; Harlow, A.F.; Benowitz, N.; Leventhal, A.; McConnell, R.; Cho, J. Effects of dual use of e-cigarette and cannabis during adolescence on cigarette use in young adulthood. Tob. Control 2023, 33, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, A.M.; Strong, D.R.; Kirkpatrick, M.G.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S.; Riggs, N.R.; Stone, M.D.; Khoddam, R.; Samet, J.M.; Audrain-McGovern, J. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. JAMA 2015, 314, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Soneji, S.; Stoolmiller, M.; Fine, M.J.; Sargent, J.D. Progression to Traditional Cigarette Smoking After Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, T.; Candel, M.; de Vries, H.; Talhout, R.; Knapen, V.; van Schayck, C.P.; Nagelhout, G.E. Exploring the gateway hypothesis of e-cigarettes and tobacco: A prospective replication study among adolescents in the Netherlands and Flanders. Tob. Control 2023, 32, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanavanich, R.; Worawattanakul, M.; Glantz, S. Longitudinal bidirectional association between youth electronic cigarette use and tobacco cigarette smoking initiation in Thailand. Tob. Control 2024, 33, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisinger, C.; Rasmussen, S.K.B. The Health Effects of Real-World Dual Use of Electronic and Conventional Cigarettes versus the Health Effects of Exclusive Smoking of Conventional Cigarettes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adermark, L.; Galanti, M.R.; Ryk, C.; Gilljam, H.; Hedman, L. Prospective association between use of electronic cigarettes and use of conventional cigarettes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00976–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunge, D.; Marganski, J.; Advani, I.; Boddu, S.; Chen, Y.J.E.; Mehta, S.; Merz, W.; Fuentes, A.L.; Malhotra, A.; Banks, S.J.; et al. Deleterious Association of Inhalant Use on Sleep Quality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddu, S.A.; Bojanowski, C.M.; Lam, M.T.; Advani, I.N.; Scholten, E.L.; Sun, X.; Montgrain, P.; Malhotra, A.; Jain, S.; Alexander, L.E.C. Use of Electronic Cigarettes with Conventional Tobacco Is Associated with Decreased Sleep Quality in Women. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advani, I.; Gunge, D.; Boddu, S.; Mehta, S.; Park, K.; Perera, S.; Pham, J.; Nilaad, S.; Olay, J.; Ma, L.; et al. Dual use of e-cigarettes with conventional tobacco is associated with increased sleep latency in cross-sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment., D.o.P.H. Healthy Kids Colorado Survey Information; Colorado State: Fort Collins, CO, USA.

- Mead, E.L.; Duffy, V.; Oncken, C.; Litt, M.D. E-cigarette palatability in smokers as a function of flavorings, nicotine content and propylthiouracil (PROP) taster phenotype. Addict. Behav. 2019, 91, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Weaver, S.R.; Self-Brown, S.R.; Ashley, D.L.; Emery, S.L.; Huang, J. Association of e-Cigarette Advertising, Parental Influence, and Peer Influence With US Adolescent e-Cigarette Use. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2233938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Piqueras, L.; Sanz, M.J. An updated overview of e-cigarette impact on human health. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Naranjo-Lara, P.; Morales-Lapo, E.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Vasconez-Gonzales, E.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Loaiza-Guevara, V.; Rincon Hernandez, W.; Becerra, D.A.; et al. Direct health implications of e-cigarette use: A systematic scoping review with evidence assessment. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1427752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhabor, J.; Yao, Z.; Tasdighi, E.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Blaha, M.J. E-cigarette Use and Incident Cardiometabolic Conditions in the All of Us Research Program. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2025, ntaf067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittoni, M.A.; Carbone, D.P.; Harris, R.E. Vaping, Smoking and Lung Cancer Risk. J. Oncol. Res. Ther. 2024, 9, 10229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, S.A.; Nguyen, N.; Oliveira da Silva, A.L. Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDoa2300229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenziger, O.N.; Ford, L.; Yazidjoglou, A.; Joshy, G.; Banks, E. E-cigarette use and combustible tobacco cigarette smoking uptake among non-smokers, including relapse in former smokers: Umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Mendez, D.; Warner, K.E. Is Adolescent E-Cigarette Use Associated With Subsequent Smoking? A New Look. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.T.; Warner, K.E.; Cummings, K.M.; Hammond, D.; Kuo, C.; Fong, G.T.; Thrasher, J.F.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Borland, R. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: A reality check. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, S.R.M.; Piper, M.E.; Byron, M.J.; Bold, K.W. Dual Use of Combustible Cigarettes and E-cigarettes: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2022, 9, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.A.; Schaefer, D.R. With a Little Help from My Friends? Asymmetrical Social Influence on Adolescent Smoking Initiation and Cessation. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyzers, A.; Lee, S.K.; Dworkin, J. Peer Pressure and Substance Use in Emerging Adulthood: A Latent Profile Analysis. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 1716–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrejon-Guirado, M.C.; Baena-Jimenez, M.A.; Lima-Serrano, M.; de Vries, H.; Mercken, L. The influence of peer’s social networks on adolescent’s cannabis use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1306439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; D’Souza, G.; Atnafou, R.; Matson, P.A.; Jones, M.R.; Moran, M.B. “It Felt Like I Was Smoking Nothing:” Examining E-cigarette Perception and Discontinuation among Young Adults. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2018, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, R.G.; de Rosa, J.C. Impact of survey length and compensation on validity, reliability, and sample characteristics for Ultrashort-, Short-, and Long-Research Participant Perception Surveys. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 2, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Human Respondents 609 (100%) N (%) | Switched: Vaping to Smoking 104 (17%) N (%) | Switched: Smoking to Vaping 178 (29%) N (%) | Dual Use 223 (37%) N (%) | Quit Tobacco 93 (15%) N (%) | Other Inhalant Use 11 (2%) N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 16–21 years | 71 (12%) | 15 (2%) | 17 (3%) | 24 (4%) | 14 (2%) | 1 (0%) |

| >21 years | 538 (88%) | 89 (15%) | 161 (26%) | 199 (33%) | 79 (13%) | 10 (2%) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 183 (30%) | 37 (6%) | 50 (8%) | 65 (11%) | 28 (5%) | 3 (0%) |

| Male | 358 (59%) | 53 (9%) | 108 (18%) | 130 (21%) | 60 (10%) | 7 (1%) |

| Transgender Female | 23 (4%) | 5 (1%) | 7 (1%) | 9 (1%) | 2 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Transgender Male | 41 (7%) | 9 (1%) | 10 (2%) | 19 (3%) | 3 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gender queer/non-binary | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 49 (8%) | 3 (0%) | 20 (3%) | 16 (3%) | 9 (1%) | 1 (0%) |

| Race * | ||||||

| Black or African American | 35 (6%) | 3 (0%) | 10 (2%) | 15 (2%) | 7 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| White | 479 (79%) | 93 (15%) | 139 (23%) | 177 (29%) | 62 (10%) | 8 (1%) |

| Asian or Asian American | 56 (9%) | 9 (1%) | 15 (2%) | 21 (3%) | 9 (1%) | 2 (0%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 39 (6%) | 3 (0%) | 11 (2%) | 14 (2%) | 11 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 13 (2%) | 3 (0%) | 3 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banjo, E.; Ahadian, Z.; Kasaraneni, N.; Chang, H.; Perera, S.; Emory, K.; Crotty Alexander, L.E. Perceptions of Health Risks and Accessibility: A Social Media-Based Pilot Study of Factors Influencing Use of Vaping and Combustible Tobacco Products. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050800

Banjo E, Ahadian Z, Kasaraneni N, Chang H, Perera S, Emory K, Crotty Alexander LE. Perceptions of Health Risks and Accessibility: A Social Media-Based Pilot Study of Factors Influencing Use of Vaping and Combustible Tobacco Products. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050800

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanjo, Enitan, Zoya Ahadian, Nikita Kasaraneni, Howard Chang, Sarala Perera, Kristen Emory, and Laura E. Crotty Alexander. 2025. "Perceptions of Health Risks and Accessibility: A Social Media-Based Pilot Study of Factors Influencing Use of Vaping and Combustible Tobacco Products" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050800

APA StyleBanjo, E., Ahadian, Z., Kasaraneni, N., Chang, H., Perera, S., Emory, K., & Crotty Alexander, L. E. (2025). Perceptions of Health Risks and Accessibility: A Social Media-Based Pilot Study of Factors Influencing Use of Vaping and Combustible Tobacco Products. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050800